Abstract

Background

‘Gut feelings’ are frequently used by general practitioners in the clinical decision-making process, especially in situations of uncertainty. The Gut Feelings Questionnaire (GFQ) has been developed in the Netherlands and is now available in English, French, German, Polish, Spanish, and Catalan, enabling cross-border studies on the subject. However, a Turkish version of the GFQ is lacking.

Objectives

A Turkish version of the GFQ.

Methods

A linguistic validation procedure was conducted, which took place in six phases: forward translation (step 1), backward translation (step 2), first consensus (step 3), cultural validation (step 4), second consensus (step 5), and final version (step 6).

Results

The absence of literal equivalent of the term ‘gut feelings’ in Turkish was determined. The word ‘intuition’ was chosen as the Turkish literal equivalent of ‘gut feelings’. There were also some challenges in finding the exact meanings of words and expressions in Turkish literature. However, we succeeded in finding adequate and responsible solutions. A Turkish version of the GFQ is available now.

Conclusion

With these validated GFQs, Turkish GPs can facilitate studies of the role of ‘gut feelings’ in clinical reasoning.

Introduction

KEY MESSAGES

The GFQ is available in many European languages but only in Turkish now.

After a linguistic validation procedure, a Turkish GFQ was created.

Although there is no equivalent Turkish expression for ‘gut feelings’, the sense of alarm and reassurance are clearly recognised in Turkish general practice.

Two types of ‘gut feelings’ have been described: a sense of alarm and a sense of reassurance [Citation1]. A sense of alarm is defined as an uneasy feeling perceived by a GP as they are concerned about a possible adverse outcome, even though specific indications are lacking. It activates the diagnostic process and initiates careful management to prevent serious health problems [Citation4]. A sense of reassurance means that GPs feel safe regarding the management and course of the disease, even if they are unsure of the diagnosis [Citation5]. Based on these definitions, a Dutch Gut Feelings Questionnaire (GFQ) was created and validated to determine the presence or absence of ‘gut feelings’ in GPs’ clinical reasoning at the end of consultation [Citation6]. After a linguistic validation procedure, the Dutch questionnaire was translated into English [Citation2]. There are two versions of the GFQ, a case vignette version and a real practice version. Using the case vignette version is recommended for educational situations, e.g. medical students and GP residents [Citation2]. The two versions of the GFQ are also available in French, German, Polish, Spanish, and Catalan (https://www.gutfeelings.eu/questionnaire/) [Citation7,Citation8].

‘Gut feelings’ are a diagnostically accurate tool for diseases such as dyspnoea, cancer, and infections in primary care [Citation9–11]. It has been reported that GPs’ ‘gut feelings’ based on patient-related symptoms and non-verbal cues predicted more cancer diagnoses than clinical guidelines [Citation9]. In addition, ‘gut feelings’ about the children’s health have a high specificity and positive likelihood ratio regarding a serious infection [Citation11]. We assume that the ‘gut feelings’ of GPs in Turkey also play a substantial role in their diagnostic process, but there is no research in Turkey on this topic as a measuring tool is lacking. This study aimed to translate the English GFQ into Turkish.

Methods

The research team (HE, MNT, SEY, FO, VM) consisted of five academic staff with primary care experience and working at two universities in Turkey. We conducted the linguistic validation procedure according to internationally accepted cross-cultural adaptation guidelines and recommendations in line with previous studies [Citation7,Citation12–14].

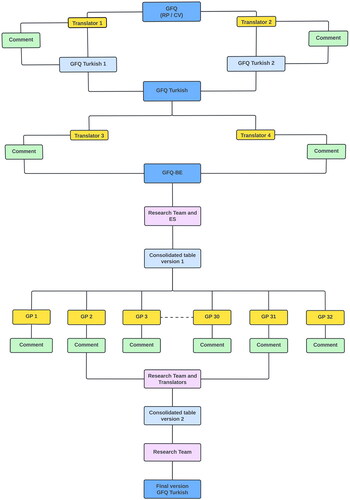

This procedure comprised six steps: Forward-translation (step 1), backward-translation (step 2), first consensus (step 3), cultural validation (step 4), second consensus (step 5), and final version (step 6). We completed the six steps between September 2020 and July 2021 ().

Figure 1. The procedural scheme followed for the English-Turkish translation of the gut feelings questionnaire. GFQ: Gut feelings questionnaire.

Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the Health Sciences Ethics Committee of Manisa Celal Bayar University (01/20/2021-No:20.478.486). Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Forward-backward translations (steps 1 and 2)

Two Turkish GPs trained in Turkey and currently working in France and the Netherlands translated the English GFQ (real practice and case vignette version) into Turkish. They were informed about the purpose of the GFQ and how it has been used in research. They were asked to perform the translations independently of each other and to give suggestions (step 1).

Then two native English speakers who had previously worked in Turkey and were familiar with medical terms translated the two Turkish versions back to English independently (step 2).

Reaching a first consensus (step 3)

The research team prepared the first translation draft, putting all the differences between translations and questions in an expanded table. The research team and the four translators evaluated the translations and made a synthesis. All items were reviewed regarding clarity, semantic, idiomatic, experiential and conceptual equivalence [Citation12]. This draft of the GFQ was accepted for both the case vignette and the real practice version based on the adequacy of each item and understanding of the items’ expressions. As a result of extensive communication between the research team and one of the authors (ES) of the original Dutch GFQ [Citation2], a consensual GFQ version was obtained.

Cultural validation (step 4)

The research team sent these consensual GFQ versions to 32 GPs in Turkey, asking them to check for grammatical errors, cultural misunderstandings, and applicability in daily practice. An accompanying e-mail explained the background of the questionnaire and the purpose of their participation.

Reaching a second consensus (step 5)

At this stage, the research team incorporated the results of the feedback from the 32 GPs and the translators’ comments into an adapted GFQ version.

Resulting in a final version (step 6)

Finally, the research team determined the final text of the two questionnaire versions.

Results

Adaptations and problems

Steps 1 to 3

The wording ‘gut feelings’ does not have a comparable equivalent in Turkish. The concepts of intuition, instinct, belief, and feeling were discussed with the research team and translator. As a result, it was deemed appropriate to choose the word ‘intuition’, which means ‘sensing that something is going to happen in the absence of symptoms’, as the most appropriate wording. So, the research team adopted the expression intuition of GPs. However, to remain faithful to the original title of the scale, the title was left as ‘Gut feelings’, and the Turkish title ‘Hekim Önsezisi Ölçeği’ (in English, ‘General Practitioners Intuition Questionnaire’) was added in parentheses.

The second challenge of the translation process was that there was no Turkish equivalent of ‘picture’ in the first item, ‘something is wrong with this picture’. The wording ‘picture’ is not widely used in Turkish when describing the concept of GPs’ clinical reasoning. Instead of ‘picture’, the words ‘in the story’ (‘öyküde’) were chosen.

Steps 4 to 6

Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, GPs’ response time took four months. We received feedback from 32 GPs who were previously informed and agreed to participate in the study. The research team systematically analysed all responses. In particular, the research team discussed items 1, 2, 4, 6, and 7 in detail.

Item 1: There is no precise equivalent in Turkish for ‘everything fits’. The research team preferred the sentence ‘everything seems suitable’ (‘her şey uygun görünüyor’) in line with the feedback from 8 of the participating GPs. It has been concluded that this item’s remaining were insufficient to make changes.

Item 2: ‘It all adds up. I feel confident about my management plan and/or the outcome’. Three participants hesitated about what the word outcome meant. They posed questions such as whether the expression here is ‘the outcome of the disease’ or ‘the outcome of the treatment plan’. However, it was preferred to stick to the original BE text for this item.

Item 4: ‘In this particular case, I will formulate provisional hypotheses with potentially serious outcomes and weigh them against each other’. In Turkish, the word ‘weigh’ is not used to express abstract concepts, so it was decided that ‘weigh’ is inappropriate to describe general practitioners’ clinical reasoning. Therefore, the Turkish equivalent of ‘compare’ (‘karşılaştırmak’) was preferred instead of ‘weigh’. Four GPs participating in the cultural validation process stated uncertainty regarding the meaning intended to be expressed using the words ‘provisional’ and ‘hypothesis’ together. Because the usual Turkish usage of the word ‘hypothesis’ is already considered to exist provisionally. Therefore, the word ‘provisional’ has been removed from this item.

Item 6: ‘…any (further) serious health problems…’. in this item, the participants gave feedback that the words ‘any’ and ‘further’ lack semantic integrity in Turkish. As a result, the Turkish equivalent of ‘any’ (‘herhangi bir’), an inclusive expression, was considered sufficient. Meanwhile, the term ‘(further)’ was removed from the text.

Item 7: Due to the participants’ feedback about routine practice, the research team preferred the Turkish equivalent of ‘earlier’ (‘daha erken’), which is more common in the Turkish daily language, instead of ‘sooner’. Also, the second challenge for this item was the semantic equivalent of ‘give me a reason’. Four participants suggested, ‘leads me to arrange’, ‘The patient’s condition is important for me to arrange…’, ‘This patient’s condition justifies me to arrange…’ and “This patient’s condition makes me think about arranging…’. It was thought that the expressions ‘makes me think’, ‘justifies me’ and ‘leads me’ have similar meanings to ‘give me a reason’ in the original BE version. Therefore, it was decided not to make any changes to this section.

The final result is a Turkish GFQ (Supplementary Files 1 and 2).

Discussion

Main findings

In the Turkish linguistic adaptation process of GFQ, it was stated that ‘gut feelings’ played an active role in the clinical decision-making process of GPs in Turkey. Still, instead of ‘gut feelings’, they use the term linguistically equivalent to ‘intuition’.

Strengths and limitations

The linguistic validation of the Turkish version of the GFQ was performed in a structured multistage process by an internationally agreed linguistic validation procedure [Citation12–14]. The research team had experience in Turkish primary care. The participating GPs could contact the research team by telephone or e-mail at every stage of the validation procedure. A limitation was that the backward translators did not have a medical background. Nevertheless, they had many years of teaching experience at universities in Turkey.

The research team followed the validation procedures used by Barais [Citation7]; therefore, structural properties were not applied in our study. However, the application of the structural feature could be planned from the perspective of the studies by Barais et al. on the feasibility of the GFQ in daily life [Citation6].

Another limitation was that we should have performed a Delphi consensus procedure in advance to reach an agreement about the definitions of ‘gut feelings’ in general practice. Based on several linguistic validation studies of the GFQ in Europe, we assumed that the sense of alarm and reassurance is considered to be cross-cultural for GPs in their decision-making process [Citation7,Citation8]. Therefore, we decided to refrain from performing a Delphi consensus procedure after consulting the developers of the original GFQ [Citation2]. Moreover, the content of the feedback by the participating GPs confirmed our assumption that the sense of alarm and reassurance is recognised in Turkish general practice.

We have considered the Turkish healthcare system during the whole validation procedure and adapted some wording in accordance with the practice of Turkish healthcare. There is no literal equivalent Turkish expression for gut feelings, which is also the case in Catalan and Spanish [Citation8]. We adopted the word ‘intuition’ in line with the Catalan and Spanish researchers.

Comparison with existing literature

Regarding item 4, instead of the word ‘weigh’, we concluded that the word ‘compare’ is more understandable in Turkish, which is also the case in the Polish version.

Regarding item 9, the French GPs discussed two situations: requesting a second opinion from a specialist in their network with non-formal emergency criteria or referring to the emergency unit. However ultimately, they decided to translate this item into ‘refer the patient to a specialist, either within the emergency unit or elsewhere’. In Poland, the translation of ‘refer the patient’ has negative connotations as ignoring and sending away the patient; the Polish authors chose a neutral formulation path for this item as ‘refer the patient elsewhere’ without mentioning the organisational aspect [Citation7]. In the Turkish translation of this item, ‘refer the patient’ was found sufficient instead of adding the emergency department. This was in line with the German and Spanish versions but contrary to the French and Polish ones [Citation7,Citation8].

Implications for practice and future research

A study to evaluate the feasibility of the questionnaire in daily practice in primary care, which determines structural properties, was planned before conducting further studies with the Turkish version of GFQ.

Repeated observational and qualitative studies have shown that the GFQ can be effectively used to assess the role of ‘gut feelings’ in GPs’ decision-making process in uncertain situations [Citation10,Citation11,Citation15]. It has been shown that the sense of alarm correlated with a life-threatening situation for patients presenting with dyspnoea and/or chest pain [Citation10], in line with other studies showing that GPs’ ‘gut feelings’ might predict clinical severe problems [Citation16–18]. A sense of alarm and a sense of reassurance can be studied in all conceivable areas of primary care, such as in geriatric medicine. A sense of alarm may guide doctors in assessing the degree of frailty in elderly individuals and evaluating to which frail elderly we should be more alert. In this case future studies could contribute to determining the accuracy of the GFQ among GPs in Turkey.

In medical education, the GFQ can raise awareness of a sense of alarm or a sense of reassurance among medical students and GP trainees [Citation19]. Another study could be planned among medical faculty seniors using case vignettes to measure the accuracy of students’ sense of alarm when confronted with myocardial infarction.

Turkish GPs can now participate in cross-border multicentre studies, such as repeating the studies done by Barais [Citation6].

Conclusion

The GFQ is available in Turkish. This tool will pave the way for national and international studies into the role of ‘gut feelings’ in GPs’ clinical reasoning.

Acknowledgements

We thank our esteemed colleagues for assisting the study’s data collection process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Stolper E, Van de Wiel M, Van Royen P, et al. Gut feelings as a third track in general practitioners’ diagnostic reasoning. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(2):197–203. doi:10.1007/s11606-010-1524-5.

- Stolper CF, Van de Wiel MWJ, De Vet HCW, et al. Family physicians’ diagnostic gut feelings are measurable: construct validation of a questionnaire. BMC Family Prac. 2013;14:1.

- Stolper E, van Leeuwen Y, Van Royen P, et al. Establishing a European research agenda on ‘gut feelings’ in general practice. A qualitative study using the nominal group technique. Eur J Gen Pract. 2010;16(2):75–79. doi:10.3109/13814781003653416.

- Stolper E, Van Royen P, van de Wiel MWJ, et al. Consensus on gut feelings in general practice. BMC Fam Pract. 2009;10(1):66. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-10-66.

- Stolper E, van Bokhoven M, Houben P, et al. The diagnostic role of gut feelings in general practice A focus group study of the concept and its determinants. BMC Fam Pract. 2009;10(1):17. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-10-17.

- Barais M, van de Wiel MWJ, Groell N, et al. Gut feelings questionnaire in daily practice: a feasibility study using a mixed-methods approach in three European countries. BMJ Open. 2018;8(11):e023488. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023488.

- Barais M, Hauswaldt J, Hausmann D, et al. The linguistic validation of the gut feelings questionnaire in three European languages. BMC Fam Pract. 2017;18(1):54. doi:10.1186/s12875-017-0626-0.

- Oliva-Fanlo B, March S, Stolper E, et al. Cross-cultural translation and validation of the 'gut feelings’ questionnaire into Spanish and Catalan. Eur J Gen Pract. 2019;25(1):39–43. doi:10.1080/13814788.2018.1514385.

- Smith CF, Drew S, Ziebland S, et al. Understanding the role of GPs’ gut feelings in diagnosing cancer in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis of existing evidence. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(698):e612–e621. doi:10.3399/bjgp20X712301.

- Barais M, Fossard E, Dany A, et al. Accuracy of the general practitioner’s sense of alarm when confronted with dyspnoea and/or chest pain: a prospective observational study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(2):e034348. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034348.

- Van den Bruel A, Thompson M, Buntinx F, et al. Clinicians’ gut feeling about serious infections in children: observational study. BMJ. 2012;345(2):e6144–e6144. doi:10.1136/bmj.e6144.

- Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, et al. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(24):3186–3191. doi:10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014.

- Hammond A, Tyson S, Prior Y, et al. Linguistic validation and cultural adaptation of an english version of the evaluation of daily activity questionnaire in rheumatoid arthritis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12(1):143. doi:10.1186/s12955-014-0143-y.

- Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, et al. Recommendations for the Cross-Cultural adaptation of the DASH & QuickDASH outcome measures. Toronto: ınstitute of Work and Health; 2007; [cited 2023 July 17]. Available from: http://www.dash.iwh.on.ca/ translation-guidelines.

- Latten GH, Claassen L, Lucinda Coumans L, et al. Vital signs, clinical rules, and gut feeling: an observational study among patients with fever. BJGP Open. 2021;5(6):1–8. doi:10.3399/BJGPO.2021.0125.

- Urbane UN, Gaidule-Logina D, Gardovska D, et al. Value of parental concern and clinician’s gut feeling in recognition of serious bacterial infections: a prospective observational study. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19(1):219. doi:10.1186/s12887-019-1591-7.

- Turnbull S, Lucas PJ, Redmond NM, et al. What gives rise to clinician gut feeling, its influence on management decisions and its prognostic value for children with RTI in primary care: a prospective cohort study. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):25. doi:10.1186/s12875-018-0716-7.

- de Groot NI, van Oijen MGH, Kessels K, et al. Prediction scores or gastroenterologists’ gut feeling for triaging patients that present with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding.United European Gastroenterol J. 2014;2(3):197–205. doi:10.1177/2050640614531574.

- Stolper CF, Van de Wiel MWJ, Hendriks RHM, et al. How do gut feelings feature in tutorial dialogues on diagnostic reasoning in GP traineeship? Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2015;20(2):499–513. doi:10.1007/s10459-014-9543-3.