ABSTRACT

In this addition to the European Journal of English Studies special issue, the author reflects on the employment of social media application Instagram by contemporary poets in peninsular Spain as a tool for projecting societal concerns specifically related to feminism and social equality movements, proliferated by technological affordances such as the graphological hashtag (#). By analysing the connections between poetry, digital culture and feminist activism, this article examines the poetry of popular Instapoetas Elvira Sastre and Leticia Sala and its underlying feminist message, as well as the implications of writing in and of the so-called “fourth wave of feminism.” Where the poetic content, visual imagery and captioned employment of hashtags are seen to perpetuate the work of offline, feminist activism, Instapoetry can be seen as an assistant or a “valid contribution” to collective action.

A continuously advancing technological culture has given rise to a new generation of Spanish poets who are reformulating the art form by claiming digital media as its writing space and main site of publication. During his Peers Annual Lecture at the University of Liverpool in 2017, the renowned poeta de la experiencia Luis García Montero contemplated how Spanish lyricists are beginning to search for “their own space.” This “new space” is allowing the phenomenon of poetry published via social media to become a highly accessible form of literature in contemporary Spanish consciousness, something that critics- such as Maher (Citation2018) in his meditative article “Can Instagram make poems sell again?”- are equating to an exploration towards larger changes that not only evince the exclusivity of print publishing in a society that predilects the Web 2.0, but the multitudinous potentialities of the online environment. While this article positions itself within peninsular Spain, certain fundamental arguments of this study can become applicable in a more global structure. Indeed, by adopting facets of established feminist praxis that considers digitality as a tool for bolstering social movements, this article posits that the digital space provides an interesting site not only for self-expression and publishing texts “at liberty,” but also as one for projecting societal concerns (Pressman Citation2014, 10). In an era of #8M, #niunamenos, #metoo and #imwithher: digital, feminist, and social equality movements are steadfastly present within the wider contemporary digital consciousness. With an underlying feminist message, the work of specific, contemporary digital Spanish poets and accounts- Elvira Sastre, Leticia Sala and the collaborators of @siempree_libree, will be ratified under this lens. In considering Jain’s examination of the “fourth wave of feminism” and established conceptualisations of cyberfeminism, this analysis will also offer an understanding of the expectation, or even obligation, for Instagram poets (Instapoetas) to utilise their platform for the feminist cause, continuing the “work” of their literary predecessors (Citation2020). For this, Bourdieusian social theory on the position and capital of these writers will be reconceptualised and applied to the texts at hand, determining the ways in which Bourdieu’s field is subverted by the intertextuality of poetry, social media and activism. Indeed, we will therefore conceive of a negotiation of female status within the social media space as well as within the field of digital activism, raising illuminating connections between such concepts.

If we pivot to Vilariño Picos’s understanding of technology as an environment that, in poetry, facilitates “el trabajo coral” [choral work]Footnote1; as a realm in which users can view, listen to, participate in, interact with, and put forth their own conceptions of the world, their self or social revelatory experiences or simply the “argument” or news, we can also conceive of social media as a space that fosters social commentary and social action (Citation2013, 218). Yochai Benkler’s conception of social media outputs as an impetus for “participatory media,” is evident within digital culture scholarship as a term which lends itself well to the notion that readers become, in the social media space, “co-conspirators,” as the technological medium allows users to participate actively (Citation2006). Whether this participation constitutes swiping left to the next poem, interacting with the poet themselves through the comments section, or moving the figurative “page” across the screen, Benkler’s term is useful in exemplifying the modifications of the modern reading process at the hands of the medium itself. Christian Fuch’s conception of the term not only nods to the “process-orientated” perspective which will be discussed in this article, but also notes its capability of being “politically-infused” (Citation2014, 11). Concerned with the potential for political communication on social media, Fuchs’ study laid and galvanised foundational, critical standpoints on the political economy of communication, proliferated by social media platforms such as Twitter, and, in line with this article’s focus, Instagram. According to Raetzsch however, “the plurality, ambiguity and heterogeneity of ways in which social media are significant today bespeaks, maybe even fundamentally, the possibility of a generalisable theoretical perspective” (Citation2016, 1).

Contributions by Bennett and Segerberg (Citation2013) may serve to clarify how this plurality functions in practice, by differentiating between collective and connective action. By aiming to “get beyond what’s new,” Bennett & Segerberg put forth a logic of connective action, understanding that whilst, unlike digital platforms, conventional “journalistic” or offline methods of activism “cannot reproduce dramatic immediacy and authenticity,” some activists continue to discount the value of digital media in activism as one that merely “favours lesser levels of commitment” (Citation2012, 25–26). Perhaps further from Fuchs’ theory, Bennett & Segerberg observe that digital media platforms (such as social media applications) can forge connective action (as opposed to offline collective)- networks that appear “far more individualised” and “without the requirement of collective identity framing or the levels of organisation resources necessary to respond to opportunities” (Citation2012, 32). The affordances of social media for personalised expression, broadcasting, and interpersonal communication, recognised by Bennett & Segerberg and, more recently, Tufekci, serve to position the digital space as an interesting site for engaging with cultural activism of the current age (Citation2017).

The relationship between Internet platforms and activism is continuously developing, underlined by Zeynep Tufekci in the recognition that “digital technologies are so integral to today’s social movements that many protests are referred to by their hashtags,” the addition of poetry to this consideration allows scholarship to examine how digital technology affects activism through cultural artefacts, as well as social platforms (Citation2017, xxvi). Indeed, activism, poetry and social media is an intersection gaining some critical attention in the Digital Humanities discipline, within and without the Spanish context. As confirmed by Piñero-Otero & Martínez-Rolan:

la apropiación de la Web 2.0 por el activismo feminista ha posibilitado una mayor participación de las mujeres en el discurso público, dotándolas de las herramientas precisas para el lanzamiento, la difusión y la consecución de apoyos para sus demandas o protestas sociales y políticas (Citation2016, 17).

[‘the appropriation of Web 2.0 by feminist activism has enabled a greater participation of women in public discourse, providing them with the precise tools to launch, disseminate and obtain support for their demands or social and political protests’] (Citation2016, 17).

Clearly, it is becoming increasingly apparent that social media and social software are tools that can “increase our ability to share, to co-operate with one another, and to take collective action, all outside the framework of traditional institutional institutions and organisations” as well as sites for the publication of contemporary literature (Shirky Citation2008, 20). For anyone that has lived through the rise of the Web 2.0, it is an obvious proclamation that digital technologies increase the number of “vectors through which information can be distributed” (Withers Citation2015, 123). In a bid to avoid a technologically utopian view, however, this article’s aim is not to suggest that digital poetic outputs lend themselves wholly to digital activism. For the poets exemplified, Elvira Sastre, Leticia Sala, and collaborators under the account @siempree_libree, one cannot presume that activism is the driving force for their creative output, rather it is considered here as one of many components or potentialities of their work. This article therefore contends that the social media space breeds the opportunity, and at times, an apparent obligation for creators to introduce positive changes through their platform (those at least, with a larger scale following). Vlavo’s critical framework posits the existence of two routes for analytically evaluating digital activism and its potentialities: “One route is to examine how technology is reshaping traditional forms of activism, and the other route is to investigate the relation between digital media and activism” (Citation2018, 5). Whilst Vlavo’s viewpoint should not be undermined, it is this article’s understanding that the two conceptions are mutually enlightening, rather than completely separate.

Returning to Bennett & Segerberg’s logic of connective action, the dynamics of activism in both offline and online spheres can be seen to be enhanced, but not transformed in the latter, allowing us to conceive that “such technologies serve as tools to help actors do what they are already doing” (Citation2012, 33). In the case of this article, the “actors” in question are poets – key players in what Leonardo Flores terms “third generation electronic literature” (Citation2018). Primary efforts towards documenting and analysing electronic literature were by N. Katherine Hayles in the seminal Electronic Literature: New Horizons for the Literary, where first-generation digital literature is acknowledged as hypertextual, and functioning in concert with “paradigms established in print” (Citation2008, 2). Following on from Hayles’ formulation of generational e-literature, Christopher Funkhouser explored the kinetic and multimedia possibilities of digital literature, focusing on web-based digital poetry and emerging platforms in conjunction with contemporary electronic or digital literature (Citation2012). In this context, Leonardo Flores’ work on “third generation electronic literature” shines through, building on theories of Hayles and Funkhouser in order to “analyse what the Instagram Poets” social and economic success tell us about new practices of digital-born authorship’ (Citation2018, 1). Indeed, the ways in which “technologies … shape digital media are diverse, rapidly evolving, and can be used to such different effects” underline the opportunity for digital media, such as poetry, as well as public discourse to be shaped in the contemporary age (Citation2018, 1). For instance, exhibits an original poem by contemporary author Elvira Sastre, thus comprising of a particular relationship between digital media (social media poetry) and activism. Elvira Sastre is a poet that operates, at least partly, online and receives substantial public support. Benjamín Prado wrote the prologue to Sastre’s La soledad de un cuerpo acostumbrado a la herida (2016), and according to the blurb of Baluarte (Citation2014), for poeta de la experiencia Luis García Montero, “la poesía de Elvira Sastre es una apuesta verdadera, más allá de modas.” [Elvira Sastre’s poetry is a good bet, a poetry beyond sweeping trends].

Different digital, feminist projects (or real-life examples of cyberfeminism) such as Mujeres en Red, Fundación Mujeres, Red Estatal de Organizaciones Feministas contra la Violencia de Género are seen to harness the capabilities of the online space to forge feminist praxis. From here, movements such as #8M (as seen in ) #metoo and #niunamenos are borne from a cyberfeminist rhetoric, understood by Sádaba and Barranquero as a movement that “cumple una serie de funciones activistas y suponen un espacio para el refuerzo de la identidad y en el que se dan intervenciones de ideario feminista” [fulfils a series of activist functions and supposes a space for the reinforcement of identity and in which interventions of feminist ideas take place] (Citation2019, 17). The employment of the substantive name #8M returns to Tufekci’s recognition of the power of networked protests, the idea that digitality is so integral to social movements that many take their name from the hashtag used on social media platforms (Citation2017). This neologism #8M, inextricably linked with the 8th March (International Women’s Day) is engaged with by all poets that form this study’s primary sources, exemplified in the Figures presented. Scholars of social media poetry understand that the caption in an Instapoema forms an important, tangential part of the text at hand (Crystal Citation2011). Sastre’s adoption of the inclusive “nos” in “nos vemos en las calles” [“we” in we’ll see each other on the streets] not only constitutes a sharing relationship between writer and reader (and thus an exemplification of Benkler’s emphasis on the “participatory culture” in the online realm (Citation2006) but is also a linguistic representation of this article’s main aim, to substantiate claims that Instagram and its intersection with contemporary poetry is a valid tool for implementing, fortifying, and maintaining social equality movements. Alongside Emba’s accompanying illustration which exemplifies a female literally “changing the direction of the fist,” in a comment on male violence; exhibiting a trajectory from receiving “el puño” and needing to “defendernos” [defend ourselves] to the exemplification of female strength, that “we will fight.” Interestingly, Withers’ research on the politics of transmission where feminism and digital culture are concerned, nods to the ‘decomposition of the “we” and the “I” in the digital space, leading in some cases to a “pseudo-individualism” (Citation2015, 19–20). However, is an Instapoema that negates this line of thought, as Sastre adopts, in both the poem’s content and in the caption, the “we” form, ending with the inspiring “lo vamos a conseguir” [we will achieve it]. This linguistic representation of solidarity, bastions of the #8M feminist movement, is seen fortified by other affordances of the social media space. Indeed, readers can openly comment on the Instapoema, providing the possibility to embark upon direct interaction with the Instapoeta and also with other readers, underlining Sastre’s reference to “compañeras” [comrades]. It should be noted here that “we,” in this context, should serve to represent the category of womxn- a term preferred by intersectional feminism to refer to all self-identifying females, including trans writers and readers that identify as female.Footnote2 Whilst it is contended that the employment of the pronoun “we” intends to precipitate inclusivity in the text, this article acknowledges that the term can appear essentialistic and is therefore conscious to reinforce the importance of situated knowledges in this context. Gouws and Coetzee (Citation2019) reflect on the importance of intersectionality in movements and mobilisation.

When discussing Internet linguistics, it would be sagacious to include some discussion of the hashtag (#), especially given its involvement in the previous Figure. A metadata tag widely used in microblogging and on social media platforms, the hashtag is a user-generated device for tagging which ultimately enables cross-referencing of content that shares a theme or subject. Hashtags employed through social media platforms Twitter or Instagram are usually used to categorise posts by adopting a keyword relevant to the photo-post.Footnote3 In the context of this composition, Elvira Sastre often adopts the hashtag to signpost readers to her print publications. #aquellaorillanuestra and #adiósalfrio and #baluarte are prevalent in Sastre’s feed- a strategic example of Duffy and Hund’s conception of “creative self-enterprise” that not only connects readers of Sastre (or followers), but also guides them to her print works available to purchase: a way in which she utilises the medium to her own self-promotive advantage (Citation2015). However, the digital poet also adopts hashtags for less performative and more activist functions. #Diadelavisibilidadlésbica, #columnasdelibertad and #sinculturanohayfuturo [Day of lesbian visibility/ columns on liberty/ without culture there is no future] are hashtags used frequently to caption Sastre’s Instapoemas. This function becomes a physical, technological representation of the possibilities for activism in the social media space- a digital tool on offer that, according to Withers, can be seen as “potent, extensive, and instantaneous in impact and reach” (Citation2015, 137). Whilst the actual impact is seen, by George and Leidner, to be potentially cognitive, emotional, financial, operational or even reputational (Citation2019), other scholars such as Shirky, posit that characteristics of this level of social media sharing (coined “slacktivism” – indicating political action through liking or sharing a politically-imbued post) may have little real-world impact (Citation2011). Whilst the very linguistic portmanteau “slacktivism” is pejorative, and carries connotations of little effort or commitment, Richard Fisher observes that this form of activism, whilst “often derided … is far more effective than it first appears,” noting that the argument that it displaces offline activism is simply untrue (BBC Citation2020).Footnote4 Regardless of this question of impact, the Instagram environment has, coupled with poetic or literary output, become a viable space for projecting societal concerns, proliferated in specific cases through the technological affordance of the hashtag, which Tufekci sees as a signal that social change is possible (Citation2017, xi). If we view the space as a vehicle for digital activist movements, Rainie’s qualitative study proves useful. “Social media remains one of the most popular means of enabling digital activism. For example, 66% of social media users have expressed political opinions and information, responded, or shared political posts, followed politicians or parties, or joined a political social media group” (Rainie Citation2012, 10). For instance, exhibits Elvira Sastre’s adoption of the #8M hashtag. According to the World Social Forum of Transformative Economies, the #8M represents an international feminist strike, taking place on 8th March (starting in Spain in 2018) on International Women’s Day. The WSFTE confirms that “an 8 M that brings together, mobilises and proposes” (Citation2020). Whilst the #8M Feminist Strike first began in Spain, the power of social media’s reach is fortified by its proliferation to today’s “world reference for feminism” (Mondragon et al. Citation2021). Even by clicking on the hashtag in Sastre’s caption can readers familiarise themselves with other posts adopting the same #8M comment. In this way does the Instagram space and its technological affordances allow for rapid and efficient dissemination of information, forming a valuable vehicle for the forging and maintaining of social, feminist movements.

Stein’s theorisation of a contemporary, digital poetics posits that: “Most of these electronic poetries place themselves in opposition to current print-based verse culture, so academic poetry now finds itself assailed not only by print challengers but also by digital poets whose work has moved off the printed page and onto the computer screen” (Citation2010, 7). Given that Sastre has also published in print, this study is cautious not to coin her a “print challenger,” nevertheless we can conceive that Instapoemas such as this are potentially transforming what can constitute the literary field, and thus what can constitute the literary in the contemporary digital age. For example, is an Instagram post demonstrating that the group “Poetic Action” Colombia painted a verse of Sastre’s poetry onto a mural in their city. Clearly marked by public attention, a post like this indicates that the traditional conception of “the literary” should be problematised, especially given this poesis’ capacity to transform the very field through the subversion of traditional publishing processes. Bagué Quílez agrees with this line of thought, in that digital poetry is suppressing the autocracy of publishers and intermediaries, underlining the common conception of the social media space as a “free” “wilderness” (Citation2018).

The above example is salient to this article’s grounding argument in its representation – and facilitated dissemination- of social mobilisation and of proffering an overt visibility of resources. That said, we must also reflect on the Figure from a transnational perspective. By tagging the profile @accionpoeticacucuta, Sastre utilises her social capital on the social media platform as a means of disseminating poetry that transcends geographical boundaries. Indeed, highlights the potentiality for the social media space to facilitate multidirectional and multitudinous dialogue between poet and user-reader and between readers. Liestøl, Morrison and Rasmussen recognise this as becoming somewhat common practise, theorising that digital media writers are employing multiple modalities to create “carefully authored multidimensional texts [which] enrich reading” (Citation2003, 158). Here, we can posit reading (or, viewing) to be enriched as readers across the world can view and interpret Sastre’s “frases,” as well as a communicative dialogue forged between different Spanish-speaking zones. Thumim’s conception of the Internet as being “thoroughly global in its structure” is seen fortified this line of thought, as we conceive of these poets’ use of the social media realm as an interesting, transnational, creative space (Citation2012, 151).

Whilst Bourdieusian social theory is infrequently connected with feminist movements and its treatises, a reconceptualisation of certain abstractions, namely the habitus, field and capital, allows for a deeper understanding of the negotiation of female status within the social media space as well as within the field of digital activism, raising illuminating connections between such concepts. Considering above and the aforementioned mural-painted verse under the lens of the habitus, field and capital paints a picture of poetry transcending boundaries, both of geography and of conventions of the literary realm itself. Firstly, the habitus refers to the deeply ingrained habits, skills and dispositions that people possess due to the accumulation of life experiences. Bourdieu concludes that, like “second nature” (Grenfell Citation2010, 39) “individuals implicitly and routinely modify their expressions in anticipation of their likely reception” (Bourdieu Citation1983, 53). This is particularly relevant to the notion of publishing work through social media, as it can be argued that authors publishing their literature on social media, which is immediate and means the poems are often viewed by many readers across the globe, need to be more mindful of the reception of their work than those publishing in print. This is a viewpoint discussed by Tarleton Gillespie in relation to platform moderation: the need to protect one group from its “antagonists” and the complexity of doing so in the online space (Citation2018). Here, we can also view a relationship of complementarity in online and offline activism, understanding that despite its affordances of broadcasting and interpersonal communication, “platforms may not shape public discourse by themselves” (Gillespie Citation2018, 167). Moreover, in Bourdieu’s theory, a field, market or game is a setting in which both agents and their social positions are located. On a structural level, the field is a term used to indicate the conditions in which linguistic utterances take place; including the expectations imposed in this microcosm. In an attack on Saussurian linguistics, Bourdieu stresses the importance of taking into account the praxis of language, in other words, the social conditions of its construction. His theory demonstrates that the habitus is always attuned to the field. Both Bourdieu and Johnson note the tensions that may arise between positions within the literary field specifically; tensions which exist as a result of an artists’ (or in the case of this chapter, a poet’s) struggle for cultural recognition within the specific field (Citation1996). It is interesting to note that these tensions may also be present within the field structure, as well as between different fields, highlighting how the Bourdieusian reader is to deconstruct these ideas (Bloustein Citation2003).

As previously mentioned, whilst it is well recognised that Bourdieusian social theory had relatively little to say about feminism and the female gender, Adkins & Skeggs’ collection, Feminism After Bourdieu adeptly demonstrates the emergence “of a renewed relationship between feminism and social theory” (Citation2004, 5). Indeed, Lovell’s essay on gender in the social field proposes that those that identify as female may be considered, under a Bourdieusian lens, as a social group (Citation2004). By positing that women (& womxn, see endnote 2) become a socio-political category in their own right, Lovell’s analysis not only brings feminism as a political movement right into the heart of feminist social theory,’ but by demonstrating such a relationship, we can conceive of a confrontation between the traditional, aforementioned conceptualisations of habitus and field, leading thus to a detraditionalisation of such norms, and of patriarchal gender norms imposed upon womxn (Citation2004, 7). Whilst we manipulate Bourdieu’s social framework to consider womxn as a socio-political group, we can also therefore view womxn as a class or grouping “constructed through successful bids for cultural and political authorisation and recognition” (Citation2004, 7). Whilst the habitus is tied up in social status and its subsequent recognition, it can also be argued that social media is a tool that facilitates such bids. Where cultural capital – better, Bourdieu’s category of “cultural producers” – is high, translated into number of followers (reader-users) as in the case of the previous case study of Elvira Sastre, the social space (or field) is seen transformed into an arena for such “bids” for recognition, or in the context of this study, as a space for the effective projection of feminist praxis. By applying a feminist interpretation of Bourdieu’s social theory coupled with activism scholarship’s understanding of the importance of attention as a key resource in social movements (Tufekci Citation2017, 30), Instapoesía gains the potential to change one’s understanding of contemporary poetry, “bridging the gap to an entirely new conception of what constitutes the literary” (Stein Citation2010, 127). In other words, the potentiality of forging inextricable and mutually illuminating connections between poetry, technology and cultural activism is equipped by this more malleable understanding of the literary in the contemporary age.

Jain posits that the digital space has, in recent years, been appropriated by feminists and the feminist movement in what she coins “the fourth wave:” where “social media allows for the swift dissemination of knowledge and information across borders, and thus enables transnational feminist networks” (Citation2020, 12). Just as in the Acción Poética Cúcuta reproduction of Sastre’s verse, with the affordance of reaching, mobilising and bolstering a large number of people (a more complicated and time-consuming procedure in offline activism), cyberfeminism has developed into a movement that, above all, aligns itself with feminist contributions, whilst employing “la potencialidad de ciertas tecnologías emergentes como espacios de encuentro, resistencia y reivindicación” [the potential of certain emerging technologies as spaces for meeting, resistance and vindication] (Sádaba and Barranquero Citation2019, 4). Returning to Vlavo’s understanding of the “two routes” of considering the performativity of digital activism, “one route is to examine how technology is reshaping traditional forms of activism, and the other route is to investigate the relation between digital media and activism,” (Citation2018, 5) we can conceive of Sastre’s sharing of the Acción Poética Colombia’s mural-painted verse as a means of digitising ‘and archiving feminism’s “already there” (Withers Citation2015, 9). “El movimiento Acción Poética es un fenómeno mural-literario urbano que comenzó en Monterrey, México en 1996. Tiene como fundador al poeta y profesor universitario mexicano Armando Alanís Pulido y consiste en pintar e intervenir en muros de las ciudades con mensajes y pensamientos poéticos” [The Poetic Action movement is an urban mural-literary phenomenon that began in Monterrey, Mexico in 1996. Its founder is the Mexican poet and university professor Armando Alanís Pulido and it consists of painting and intervening on city walls with poetic messages and thoughts] (Acción Poética Cúcuta). Whilst Acción Poética Cúcuta’s activism is less explicitly feminist in nature than perhaps in Jain’s perception of digital media and activism, it nevertheless exemplifies a movement, forged in the physical environment but facilitated by the digital space, promoting activist campaigns. According to Caracol Radio, a new campaign, “Arte en Casa” promotes the sharing of artistic output of young people in the local community, particularly during the recent COVID-19 lockdown. The campaign also aims at fostering a passion for reading in young people of the community, the director claiming that: “esta es una forma de expresar como el arte sigue uniendo desde la distancia” [This is a way of expressing how art continues to unite from a distance] (Caracol Cúcuta Citation2020). The Acción Poética movement is a fitting example of the convergence of poetry, social equality activism and social media, underpinning the ways in which, in contemporary literature, the three can function in concert with one another to project societal concerns and goals, to buttress a community and endorse the spirit of the local coterie. In this way, we can conceive of the ease with which digital activism, propagated by the social media space, can become transnational. Linking Spain directly with Colombia (and, in terms of digital access, with many geographical spaces connected via the Internet) the possibilities of utilising the social media space as a vehicle for expressing societal concerns and for organising or bolstering equality movements become clarified.

As demonstrated in discussion of , Elvira Sastre is a poet that habitually employs the #8M hashtag in her politically infused poem-posts. Here we can also see a repeated use of the inclusive “nosotros” [us] form in “miradnos” [look at us]. Linguistically, the opening of this poem, reproduced onto a placard in spirit and in honour of the International Women’s Day March, is formed from the imperative tense and can thus be categorised as a command, a striking opening imbued with individual and politicised strength. This sense of emotion is seen replicated, again, in the caption, where Sastre affirms that “el patriarcado, hermanas, se va a caer” [the patriarchy, sisters, will fall]. Once again, the employment of “hermanas,” as in “compañeras,” fosters a sense of solidarity, a term which evinces the unification of a shared grouping, or as in Lovell’s analysis, a socio-political group in its own right (Citation2004). Again, however, this language cannot be deemed universally inclusive, therefore this article is conscious of the nuances of “we” in intersectional feminism. Despite borders, close contact or spatial distance, Sastre at least views fellow womxn, and her feminist followers, as “hermanas,” exemplifying what Corral Cañas views as a “cercanía” between writer and reader, propagated by the online space (Citation2015). Visually homogenous to Elvira Sastre’s #8M post on 8 March 2022, the discernible placard poems of the Instagram account @siempree_libree form an exhibition of the language used by protestors at various demonstrations.

Contributions from postmodern scholars such as N. Katherine Hayles track the postprint condition and examine an “interweaving” between digital and print technologies, proffering an important and original consideration of the role of digital media in literary studies, sociology and cultural theory (Citation2008). Aligned with digital theories of Hayles, viewing poetry as a text that is “eventilised” in the digital space allows us to track relationships between poetry, digitality and social activism with specific relation to the placard poems of @siempree_libree, evinced in (Citation2008). In agreeance with e-lit scholarship, the possibility to bolster collective social action afforded by the interactivity and affordance of reaching “broader audiences” in the digital space, allows this article to contend that poetry in the digital space moves from “object” or artefact to “event” (Mandiberg Citation2012, 1). With the affordance of reaching, mobilising and bolstering a large number of people (a more complicated and time-consuming procedure in offline activism), cyberfeminism “foster[s] the power of poetry’s intervention into social norms, practices, and ideas, many contemporary women poets have laboured to make explicit the link between poetic expression and social change” (Kinnahan Citation2004, 3).

A salient element of the @siempree_libree feed, as can be seen in , is the sheer visuality of resistance in this medium. Fidler, in coining the term “mediamorphosis,” explores the ways in which new digital forms allow for the concept of media convergence to be brought to light (Citation1997). Offering users the ability to employ both text and still images with audio and video clips is a characteristic salient not only to general social media output, given the affordances of the technology, but also more specifically to digital Instapoesía. The term “mediamorphosis” exemplifies this convergence, or merging of multiple modalities, a process made possible by the digital environment. Digital poetic modes envision image and word as not merely complementary but interchangeable artistic elements (Stein Citation2010, 7). Ultimately, the visual element of the text can be seen not only to bring to light the socio-political tone of the language but also to exemplify this on its own merit, highlighting how the two modalities, as in Stein’s early approximation, serve as “interchangeable artistic elements” (Citation2010, 7). Ultimately, the Instagram space is seen to foster Fidler’s process of “mediamorphosis,” where the merging of different artistic modes is seen, similar to earlier mention of the Acción Poética Cúcuta, to remould our contemporary conception of what constitutes “the literary” whilst making visible the socio-political, or in this case, feminist tone of the message.

Like Elvira Sastre, Leticia Sala is a prominent Spanish poet that often operates online. Although Sala has published in print, and so it cannot be said that her work is confined solely to the social media space, it is nevertheless clear that her work is dedicated to digitality and forms a compelling example of digital poetics as an emerging literary field. Sala’s Instapoema in , captioned (and therefore we can safely assume, entitled) legado, can be seen to adopt Kinnahan’s notion of the explicit connection between poetic writing and social change (Citation2004). Referencing “la mujer de ayer” [the woman of yesterday] not only underlines Withers’ conception of social media’s power to bolster feminisms “already- there,” especially in direct reference to “la fuerza,” [the strength] but also suggests contemporary feminists’ continuation of the “legado” [legacy] of feminists that came before. Indeed, the one-stanza poem formulates an ode to the feminist movement, fortified by readers’ comments employing the heart emoji, in agreeance or solidarity. References to “ayer,” “hoy” and “mañana” [yesterday/today/tomorrow] not only imply that much work has been achieved by the feminist movement and its activists, and that the figurative strength of Sala’s forebears has been bequeathed to contemporary feminists, but also suggests that there is much still to be done for the feminist cause. This chronological trajectory adopted by Sala also pays lip service to the connection between womxn – in this case through time, but also across different spatial boundaries, at the hands of the technological medium. Indeed, just as Sastre’s linguistic choices forged an inclusive and identifiable rhetoric, so here does Sala refer to “la mujer de ayer,” a more generalised expression that seeks to unite, rather than alienate with specificities. It is unsurprising that Sala posted legado also on the Día Internacional de la Mujer (8th March)- and was reposted by Vogue alongside the aforementioned 8 M stream and the hashtag #JuntasHacemosHistoria, a neologism which buttresses equality, reminiscent of Sastre’s caption “lo vamos a conseguir.” The fact that this Instapoema was taken up by an iconic and long-standing publication such as Vogue is not insignificant in this context, demonstrating another way in which social media is a consequential actor in the realm of feminist activism.

Sala’s publication, Scrolling After Sex, forms a print collection of her Instapoemas and photographs (Citation2018). “Mujer: Infinito” is a poem that both carries the textual characteristics of an Instapoema, whilst exemplifying Sala’s discernment of both technology and the feminist cause.

El número de tipos// de mujer existentes es infinito// y su complejidad tambien lo es.

Mujer: Infinito.

[The number of types// of existing women is infinite// and its complexity is also infinite.

Woman: Infinite].

Not only is the short stanza in reminiscent of Sellers’ conception of “micropoetry,” a short poetic form caused by the spatial limitations of the screen and social media character limits, thus reminding readers of the social media space in which Sala largely operates, but we here conceive both the “Mujer” and technology becoming protagonists in the text, a poetic culmination of the connections this analysis makes. Clearly, the lexis “Mujer,” capitalised and set apart by Sala’s employment of enjambment, is significant. However, the concept of infinity as explored by Sala is equally relevant to the notion that Instapoesía can propagate a kind of activist potentiality. Goldsmith, in his noteworthy theory on managing language in the digital age, purports that contemporary writers, “focused all day on powerful machines with infinite possibilities, connected to networks with a number of equally infinite possibilities- the writer’s role is being significantly challenged, expanded and updated” (Citation2011, 24). The notion of “infinity” appears extensively in the academic discourse surrounding the digital age; one that affirms the plethora of texts already available online. Indeed, the suggestion of “creative freedom” and of “participatory culture” proffered by digital culture theorists is inextricably linked with both a technology literate culture of today and the social media space (see Benkler Citation2006; Fuchs Citation2014). Here, Sala merges readers’ conception of infinity in the context of technology and projects its connotations onto the perception of “Woman.” Whilst implicit, we can interpret Sala’s “infinite” kinds of womxn, powerful (via capitalisation) and complex, as a figure whose characteristics subvert the misogynistic rhetoric that perceives womxn as weak and simplistic and vapid. This infinity may also be seen to account for and include all types of self-identifying females and trans women, acknowledging the struggle and the need for empowerment of these diverse identities. Brouillete’s theorisation of literature and the creative economy affirms that demand for a limitless human potential in literature “imagin[es] new ideals of autonomy and authenticity to counter the old critique of massification” (Citation2014). “Mujer: Infinito” is arguably a poetic representation of Sala’s ideal, that the conceptual complexity of womxn (and by virtue, femininity in today’s society permeated by the Web 2.0), forming what Özkula would agree as “a representation of digital solidarity” (Citation2021, 67).

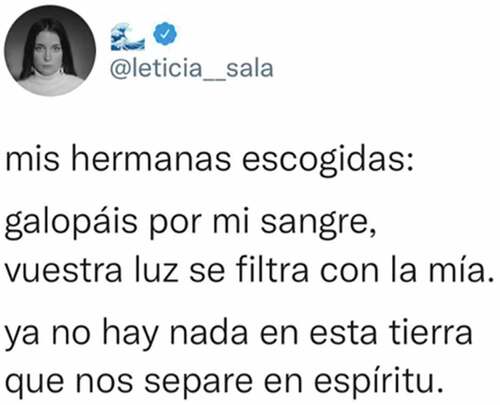

This representation is prevalent throughout Sala’s poetry. Similar to Sastre’s “lo vamos a conseguir” in , Sala’s lexical choices in addressing “mis hermanas escogidas,” [my chosen sisters] in seem to attempt to bolster Sala’s readers, the piece being peppered with a rhetoric of freedom and strength (“galopáis” “tierra” “vuestra luz” “espíritu”) [you gallop, earth, your light, spirit]. Rodríguez-Gaona’s approach to the poetry of digital natives forms a framework that understands the contemporary, digital poet to be also “influencer y community manager poético” [influencer and poetic community manager] (Citation2019). Indeed, the digital space has forged the conception of the (linguistically appropriated) #influencer within a larger framework of Celebrity Studies (Elliott Citation2020). Digital culture theorists such as Aarseth understand the creator-writer’s “pleasure of influence” over its readership, a bridge to the conceptualisation of “Instafame” within Brody’s conception of the “attention economy” (Citation1997). Understanding digital writers as gaining notoriety online quantitatively, that is, through gaining and maintaining “followers” in their readership, is imperative to exploring the fundamentals of electronic literature, as well as underlining the notion of Bourdieu’s social theory of capital in today’s smartphone age. Although a more in-depth discussion of the writer as influencer is outside the scope of this particular analysis, it is useful nevertheless to consider that the role of the poet is atomised online. Where qualities of sharing and interaction are propagated as expectations in developing social media culture, we are rapidly viewing the supposition that writers are to bolster their own readership or “network community,” as in Rodríguez-Gaona’s postulation. Indeed, the very term “social media” exemplifies what Van Dijk understands to be “user-centred platforms,” where digital creators “can be seen as online facilitators or enhancers of human networks – webs of people that promote connectedness as a social value” (Citation2013). With this in mind, the conceptual haziness and seeming open-endedness of both the term digital activism, and the expectations of advocates in the social media space, should be ratified. For instance, “Adi and Miah (Citation2011) explain that sharing a website through a tweet may be counted as activism or may not” (Özkula Citation2021, 63).

That an Instapoeta can also be considered a “community manager poético” is relevant to some scholars’ analytical viewpoint on the expectations or obligations for writers in such a position (or those with a certain level of cultural capital) to use their platforms for the projection of societal concerns (Rodríguez-Gaona, Citation2019). “The idea that artists should be involved not only in their own career development as solo authors but also in the forwarding of social goals is one that neoliberal government have tended to embrace; self-managed career development and commitment to social goals are promoted as entirely compatible directives … ” (Brouillete Citation2014, 15). In concert with this line of thought, Fidèle A. Vlavo’s framework on performing digital activism is careful to affirm that “digital technologies can facilitate or hamper the organisation of protest” and this article is keen to align itself with this centralist viewpoint (Citation2018, 3). Whilst providing a digital space that facilitates mobilisation, sharing and the dissemination of information, there are, nevertheless, complexities to considering the social media space as a one-size-fits-all site for projecting societal concerns and forging cultural equality campaigns. Global Voices published an article which exhibited photos (taken on camera and from social media) of the #8M protests throughout Latin America. Whilst the efficacy of such demonstrations is not the focus of this enquiry, it is nevertheless plain that the purpose of this movement does not align across national contexts. Activists in Chile marched against femicide and gender violence – a placard posted read “Y la culpa no era mía, no donde estaba, no como vestía,” [it wasn’t my fault, not where I was nor what I was wearing] – while Ecuadorians protested against extractivist businesses. A popular slogan from the Colombian demonstration read as poetic verse:

[not of the Church, not of the State, nor the husband, nor of the boss. My body is mine, and only mine, and the decision is mine, only].

While it is both necessary and justified to rally others to denounce male violence, Global Voices’ presentation of these varying (although often intersecting) goals nevertheless begins to project the problematic nature of online or social media activism. Moreover, questions of accessibility and class are pertinent to critical thought concerned with these issues, as well as the online space in general. In Mandiberg’s missive on social media and its effects on the contemporary “user,” it was “beginning with the printing press, technological innovations have enabled the dissemination of more and more media forms over broader and broader audiences” (2012, 1). The concept of accessibility is pertinent to scholarship that examines technology. As previously mentioned, according to Thumim, social media is “thoroughly global in its structure” (Citation2012, 151). However, it cannot be said that the digital environment is wholly accessible. Where García-Landa understands technology to possess a kind of “universal accessibility,” (Citation2006, 146), Stein, (perhaps more sensibly) exerts that this is a “guise,” considering the complexity of presuming universal access to technology (Citation2010, 87). Much of Manuel Castells’ work treats what Gere coined the “Digital Citizen” as an entirely fractured group from the “ordinary” person (Citation2002). Indeed, disparity in Internet access must be considered through the lens of socio-economic class and geographical location, something which can be equated to “a barrier” in reaching out to the masses (Jain Citation2020). This is perhaps most poignantly presented in Hill’s examination of the “menace of cyberspace” (Citation2013, 16). Despite the validity in considering Instapoetry as an important tool for feminist movements, critical scholarship must simultaneously consider the virtual environment as wholly accessible is ungrounded, and therefore this article must remain sensitive in understanding its reach is only to those with the necessary means.

Overall, this article discusses certain affordances of the social media environment as a literary forum for publishing and promoting one’s work, for self-expression and for projecting wider cultural concerns. By appropriating hashtags, considering feminist movements in their poems’ content, collaborating with artists to embark on a mediamorphosis that produces visual artefacts of “resistance,” (see ) the Spanish poets in this study are seen to engage with contemporary, feminist movements across the globe, ultimately underlining the potentiality of Instapoetry as a force for political engagement. Whilst the question of real-world impact, the problematic underpinnings of mobilising such a vast number of people with varying, international goals, and the issue of supporting minority groups within the “fourth wave of feminism,” remains unclear, digital activism and social feminism scholars must distance these inquiries from a technologically utopian view (Jain Citation2020). Nevertheless, this argument demonstrates that the social media space, coupled with poetic output, can be an effective medium for expressing politically infused views, for mobilising, promoting and presenting varying facets of social equality campaigns (specifically aligned with a feminist purpose) that can transcend spatial or geographical boundaries. Where the poetic content, visual imagery and captioned employment of hashtags are seen to perpetuate the work of offline, feminist activism, Instapoetry can be seen as an assistant or a “valid contribution” to collective action: a vehicle rather than the vehicle for feminist movements (Özkula Citation2021, 75).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Louise Evans

Louise Evans is a PGR student at University of Liverpool. Her research focuses on the ways in which Spanish Instagram poetry (Instapoesía) is changing the face of contemporary literature through certain linguistic and visual changes afforded by the digital medium. Outside of her studies, Louise works as a Spanish teacher for the University of Liverpool’s Open Languages programme. She often writes about poetry published through social media (albeit in the Anglophone context) for monthly Brizo Magazine.

Notes

1. English translations from Spanish original are author’s own.

2. Whilst it is contended that the employment of the pronoun “we” intends to precipitate inclusivity in the text, this article acknowledges that the term can appear essentialistic and is therefore conscious to reinforce the importance of situated knowledges in this context. Gouws and Coetzee (2019) reflect on the importance of intersectionality in movements and mobilisation.

3. Although a full and detailed breakdown on hashtag use in the Spanish literary field is outside of the current project scope, it is nevertheless necessary to mention here, given the previous discussion on technologically mediated language.

4. For more on “slacktivism” or clicktivism’ see Shirky (2011) or George and Leidner (2019).

References

- Aarseth, Espen. 1997. Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature. Maryland: John Hopkins University Press.

- Adi, Ana, and Andy Miah. 2011. “Open Source Protest: Human Rights, Online Activism and the Beijing 2008 Olympic Games.” In Transnational Protest and the Media, edited by S. Cottle and L. Lester, 213–224. New York: Peter Lang.

- Adkins, Lisa, and Beverley Skeggs, eds. 2004. Feminism After Bourdieu. London: Blackwell Publishing.

- Benkler, Yochai. 2006. The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom. New York: Yale University Press.

- Bennett, W. Lance, and Alexandra Segerberg. 2013. The Logic of Connective Action: Digital Media and the Personalisation of Contentious Politics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Bloustein, Geraldine. 2003. Girl-making: A cross-cultural Ethnography on the Processes of Growing up Female. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1983. “The Field of Cultural Production, Or: The Economic World Reversed.” Poetics 12 (4–5): 311–356. doi:10.1016/0304-422X(83)90012-8.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1996. The Rules of Art, Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Brouillete, Sarah. 2014. Literature and the Creative Economy. California: Stanford University Press.

- Cañas, Celia Corral. 2015. “Los viajes mediáticos de la micropoesía de Ajo.” Studia Iberica et Americana (SIBA) 2: 371–392.

- Caracol, Cúcuta. 2020. https://caracol.com.co/ciudades/cucuta/

- Crystal, David. 2011. Internet Linguistics: A Student Guide. London: Routledge.

- Duffy, Brooke Erin, and Emily Hund. 2015. “Having It All’ on Social Media: Entrepreneurial Femininity and Self-Branding among Fashion Bloggers.” Social Media + Society 1 (2): 205630511560433. doi:10.1177/2056305115604337.

- Elliott, Anthony. 2020. Routledge Handbook of Celebrity Studies. London: Routledge.

- Fidler, Roger. 1997. Mediamorphosis: Understanding New Media. California: Pine Forge Press.

- Fisher, Richard. 2020. “The Subtle Ways that ‘Clicktivism’ Shapes the World’.” BBC FUTURE, September 16. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200915-the-subtle-ways-that-clicktivism-shapes-the-world

- Flores, Leonardo. 2018. “ELO18 Panel: Towards E-Lit’s #1 Hit.” Accessed 29 October 2022. https://leonardoflores.net/blog/presentations-2/elo18-panel-towards-e-lits-1-hit/

- Fuchs, Christian. 2014. Social Media: A Critical Introduction. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Funkhouser, Christopher. 2012. New Directions in Digital Poetry. Cambridge: A&C Black.

- Garcia, Landa, and Jose, Angel. 2006. Linkterature: From Word to Web Or: Literature in the Internet - Internet as Literature - Literature as Internet - Internet in Literature. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1025231

- George, J. J., and Dorothy Leidner. 2019. “From Clicktivism to Hacktivism: Understanding Digital Activism.” Information and Organization 29 (3): 100249. doi:10.1016/j.infoandorg.2019.04.001.

- Gere, Charlie. 2002. Digital Culture. London: Reaktion.

- Gillespie, Tartleton. 2018. Custodians of the Internet: Platforms, Content Moderation, and the Hidden Decisions that Shape Social Media. London: Yale University Press.

- Goldsmith, Kenneth. 2011. Uncreative Writing: Managing Language in the Digital Age. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Gouws, Amanda, and Azille Coetzee. 2019. “Women’s Movements and Feminist Activism’ in Empowering Women for Gender Equity.” Agenda 33 (2): 1–8. doi:10.1080/10130950.2019.1619263.

- Grenfell, Michael. 2010. “Bourdieu, Language and Linguistics.” In Bourdieu, Language and Linguistics, edited by Michael Grenfell, 35–66. London, New York: Continuum International Publishing Group.

- Hayles, N. Katherine. 2008. Electronic Literature: New Horizons for the Literary. Paris: University of Notre Dame Press.

- Hill, Symon. 2013. Digital Revolutions: Activism in the Internet Age. Oxford: New Internationalist.

- Jain, Shruti. 2020. “The Rising Fourth Wave: Feminist Activism on Digital Platforms in India.” ORF Issue Brief No. 384, July. Observer Research Foundation.

- Kinnahan, Linda. 2004. Lyric Interventions: Feminism, Experimental Poetry and Contemporary Discourse. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press.

- Liestøl, Gunnar, Andrew Morrison, and Terje Rasmussen, eds. 2003. Digital Media Revisited: Theoretical and Conceptual Innovation in Digital Domains. London: MIT Press.

- Maher, John. 2018. “Can Instagram Make Poems Sell Again?” Publishers Weekly 265 (6): 4–9.

- Mandiberg, Michael. 2012. The Social Media Reader. New York: NYU Press.

- Mondragon, Nahia Idolaga, Naiara Berasategi Sancho, Nekane Beloki Arizti, and Maitane Belasko Txertudi. 2021. “#8M Women’s Strikes in Spain: Following the Unprecedented Social Mobilization through Twitter.” Journal of Gender Studies 16. doi:10.1080/09589236.2021.188146.

- Özkula, Suay. 2021. “What Is Digital Activism Anyway?: Social Constructions of the “Digital” in Contemporary Activism.” Journal of Digital Social Research 3 (3): 60–84. doi:10.33621/jdsr.v3i3.44.

- Picos, María Teresa Vilariño. 2013. “Tecnologías Literarias: La Oralidad En la Poesía Digital.” Pasavento: Revista de Estudios Hispánicos 1 (2): 217–229. doi:10.37536/preh.2013.1.2.636.

- Piñero-Otero, Teresa, and Xabier Martínez-Rolan. 2016. “Los Memes En El Activismo Feminista En la Red: #viajosola Como Ejemplo de Movilización Transnacional.” Cuad.inf. (39): 17–37. doi:10.7764/cdi.39.1040.

- Pressman, Jessica. 2014. Digital Modernism: Making It New in New Media. Oxford Scholarship Online, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Quílez, Luis Bagué. 2008. “La Poesía Después de La Poesía Cartografías Estéticas Para El Tercer Milenio.” Monteagudo. Revista De Literatura Española, Hispanoamericana Y Teoría De La Literatura (13): 49–72. https://revistas.um.es/monteagudo/article/view/67601

- Quílez, Luis Bagué. 2018. “Atrapados En la Red: Los Mundos Virtuales En la Poesía Española Reciente.” Kamchatka: Revista de análisis cultural 11 (11): 331–349. doi:10.7203/KAM.11.11424.

- Raetzsch, Christoph. 2016. “Is Data the New Coal? – Four Issues with Christian Fuchs on Social Media.” Networking Knowledge 9 (5): 1–21.

- Rainie, Lee, Aaron Smith, Kay Lehman Schlozman, Henry Brady, and Sidney Verba. 2012. Social Media and Political Engagement. Vol. 19. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project. http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media/Files/Reports/2012/PIP_SocialMediaAndPoliticalEngagement_PDF.pdf

- Rodríguez-Gaona, Martín. 2019. La lira de las masas: Internet y la crisis de la ciudad letrada. Una aproximación a la poesía de los nativos digitales. Spain: Páginas de Espuma.

- Sádaba, Igor, and Alejandro Barranquero. 2019. “Las redes sociales del ciberfeminismo en España: Identidad. repertories de acción.” Athenea Digital 19 (1): e2058. doi:10.5565/rev/athenea.2058.

- Sala, Leticia. 2018. Scrolling After Sex. Barcelona: Terranova Editorial.

- Sastre, Elvira. 2014. Baluarte. Spain: Valparaiso Ediciones.

- Shirky, Clay. 2008. Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing without Organizations. New York, NY: Penguin Press.

- Shirky, Clay. 2011. “The Political Power of Social Media: Technology, the Public Sphere and Political Change.” Foreign Affairs 90 (1): 28–41. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25800379

- Stein, Kevin. 2010. Poetry’s Afterlife: Verse in the Digital Age. California: University of Michigan Press.

- Thumim, Nancy. 2012. Self-Representation and Digital Culture. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Tufekci, Zeynep. 2017. Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest. London: Yale University Press.

- Van Dijck, José. 2013. The Culture of Connectivity: A Critical History of Social Media. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Vlavo, Fidèle. A. 2018. Performing Digital Activism: New Aesthetics and Discourses of Resistance. London: Routledge.

- Withers, Deborah. 2015. Feminism, Digital Culture and the Politics of Transmission: Theory, Practice and Cultural Heritage. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

- WSFTE- World Social Forum of Transformative Economies. 2020. https://transformadora.org/en/about