Abstract

Objective

Many existing tests of social cognition are not appropriate for clinical use, due to their length, complexity or uncertainty in what they are assessing. The Edinburgh Social Cognition Test (ESCoT) is a new test of social cognition that assesses affective and cognitive Theory of Mind as well as inter- and intrapersonal understanding of social norms using animated interactions.

Method

To support the development of the ESCoT as a clinical tool, we derived cut-off scores from a neurotypical population (n = 236) and sought to validate the ESCoT in a sample of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD; n = 19) adults and neurotypical controls (NC; n = 38) matched on age and education. The ESCoT was administered alongside established tests and questionnaire measures of ASD, empathy, systemizing traits and intelligence.

Results

Performance on the subtests of the ESCoT and ESCoT total scores correlated with performance on traditional tests, demonstrating convergent validity. ASD adults performed poorer on all measures of social cognition. Unlike the ESCoT, performance on the established tests was predicted by verbal comprehension abilities. Using a ROC curve analysis, we showed that the ESCoT was more effective than existing tests at differentiating ASD adults from NC. Furthermore, a total of 42.11% of ASD adults were impaired on the ESCoT compared to 0% of NC adults.

Conclusions

Overall these results demonstrate that the ESCoT is a useful test for clinical assessment and can aid in the detection of potential difficulties in ToM and social norm understanding.

Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) experience difficulties in social functioning as a core feature of ASD (American Psychiatric Association [APA], Citation2013). The central processes thought to be necessary for effective social functioning are referred to as social cognition (Adolphs, Citation2009; Baez et al., Citation2016; Baez et al., Citation2012; Henry et al., Citation2015; Van Overwalle, Citation2009). In everyday social interactions, we use social cognitive abilities such as theory of mind (ToM; i.e., the ability to recognize other people’s mental states to understand and predict their behavior) and the understanding of social norms (Baez et al., Citation2012, Citation2013) to interact and respond appropriately to others.

ToM is an important social cognitive ability, and ToM difficulties can cause significant social deficits which profoundly limit functional capacity to engage in meaningful interpersonal relationships and quality of life (Henry et al., Citation2015). ToM is a multi-dimensional concept, with processes differing based on cognitive or affective judgments (Shamay-Tsoory et al., Citation2010). Cognitive ToM is defined as the ability to make inferences about the intentions and beliefs of another individual. Affective ToM refers to the ability to make inferences about what another individual is feeling (Kalbe et al., Citation2010; Sebastian et al., Citation2011; Shamay-Tsoory et al., Citation2010). Considerable research has shown that ASD adults have difficulties with both aspects of ToM (Baron-Cohen et al., Citation2001; Mathersul et al., Citation2013; Murray et al., Citation2017).

The specific ToM difficulties that ASD adults experience have been studied extensively over the last several decades (Murray et al., Citation2017). However, the literature consists of many incongruent findings (Baron-Cohen et al., Citation2001; Couture et al., Citation2010; Roeyers et al., Citation2001); potentially as a consequence of the tests used to assess ToM. Early studies examining ToM in adults used false-belief tests designed for children and found that ASD adults performed as well as neurotypical controls (NC) (Happé, Citation1994; Jolliffe & Baron-Cohen, Citation1999; White et al., Citation2009) but still show marked problems in social interactions in everyday life (Dziobek et al., Citation2006; Palmen et al., Citation2012). To overcome this limitation in sensitivity, researchers developed more advanced tests and demonstrated difficulties in adults with ASD on the Reading the Mind in the Eyes (RME) (Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright, Hill, et al., Citation2001), the Awkward Moments Test (Heavey et al., Citation2000), the Movie for the Assessment of Social Cognition (MASC) (Dziobek et al., Citation2006), Reading the Mind in Films Test (RMF) (Golan et al., Citation2006), The Awareness of Social Inference Test (TASIT) (Mathersul et al., Citation2013) and the Strange Stories Test (Murray et al., Citation2017).

Yet, these advanced tests are not without their limitations. For instance, ASD adults can pass forced-choice social cognition tests such as the RME (Baez et al., Citation2012; Izuma et al., Citation2011; Klin, Citation2000; Schilbach et al., Citation2012), but have difficulties on tests which require spontaneous attributions of mental states (Senju et al., Citation2009). Moreover, ToM tests using written stories do not capture contextually specific ToM abilities used in everyday social interactions (Frith, Citation2004; Klin, Citation2000; Lugnegård et al., Citation2013). Individuals can pass the Strange Stories test but still exhibit difficulties in real-world social interactions (Scheeren et al., Citation2013). The abstract nature of tests which use forced-choice answers and lack context limits their ecological validity because the relationship to real-world functioning is unclear (Mathersul et al., Citation2013). To address this limitation, McDonald et al. (Citation2003) developed the TASIT, which uses short-clips of social interactions. However, it is a lengthy test with an administration time of 60–75 minutes (Mathersul et al., Citation2013; McDonald et al., Citation2003), which limits the TASIT’s application in time-sensitive clinical environments. The MASC (Dziobek et al., Citation2006) is similar to the TASIT; yet, it is a verbal interaction between characters that is dubbed into English. As such, important contextual information relating to the interactions may have been lost in translation, limiting its use in English speaking populations.

Other limitations include current tests of social cognition potentially being related to intellectual abilities. Verbal comprehension significantly correlates with or predicts performance on the RME (Baker et al., Citation2014), Strange Stories test (Kaland et al., Citation2002), RMF (Golan et al., Citation2006) and the TASIT (McDonald et al., Citation2003). Perceptual reasoning also significantly correlates with performance on the RME (Baker et al., Citation2014). Such findings may limit the interpretation from these tests.

While most existing tests have focused on assessing ToM, social cognition consists of several different abilities that are simultaneously required during social interactions. Other social cognitive abilities have received less attention in the literature. An individual’s interpersonal (how another person should behave) and intrapersonal (how they themselves should be behave) understanding of the social norms that govern their behavior are important social cognitive abilities. Violating a social norm can be detrimental to existing relationships or opportunities to form social relationships. Inter- and intrapersonal understanding of social norms have been examined separately in ASD adults, showing mixed findings (Baez et al., Citation2012; Gleichgerrcht et al., Citation2013; Lehnhardt et al., Citation2011; Thiébaut et al., Citation2016; Zalla et al., Citation2009). To our knowledge, there is currently no clinical test of inter- and intrapersonal understanding of social norms within the same test. Similarly, these abilities have never been examined alongside ToM abilities within the same test. Researchers typically investigate social norm understanding and ToM using different tests. For example, Baez et al. (Citation2012) found that ASD adults were not impaired on affective ToM measured by the RME or intrapersonal understanding of social norms assessed by the Social Norms Questionnaire (Rankin, Citation2008). This makes direct comparisons problematic, since these different tests may vary in difficulty.

Aims of the current study

The Edinburgh Test of Social Cognition (ESCoT) (Baksh et al., Citation2018) is a recently developed test of social cognition which assesses cognitive and affective ToM and inter- and intrapersonal understanding of social norms within the same test. In NC adults between the ages of 18–85, it was demonstrated that poorer performance on inter- and intrapersonal understanding of social norms and ESCoT total scores was predicted by the presence of more autism-like traits. Increasing age predicted poorer performance on interpersonal understanding of social norms, cognitive and affective ToM, as well as ESCoT total scores. In addition, female participants were better at inferring what another person was feeling. Finally, performance on the ESCoT was not predicted by verbal comprehension or perceptual reasoning abilities unlike established tests (Baksh et al., Citation2018). The aim of the present study was to validate the ESCoT in a sample of ASD adults. While new tests have been published such as Strange Stories Film Task (Murray et al., Citation2017) and Story-based Empathy Task (Dodich et al., Citation2015), these tests only assess ToM. Moreover, none of the tests assess within-subjects’ social cognitive abilities in different contexts, as well as assessing four social cognitive abilities within the same test.

Aims

To examine the convergent validity of the ESCoT against established tests of social cognition. We predicted that better performance on the ESCoT would correlate with better performance on the traditional tests of social cognition.

To compare ASD adults and NC adults on the ESCoT and established tests of social cognition. Based on previous findings in the literature, we predicted that ASD adults would be impaired on cognitive ToM; affective ToM and interpersonal understanding of social norms, but not intrapersonal understanding of social norms compared to NC adults.

To evaluate the psychometric properties of the ESCoT and compare these to traditional social cognition tests by examining the influence of intelligence, ASD traits, empathy and systemizing traits on performance.

Method

Edinburgh Social Cognition Test (ESCoT)

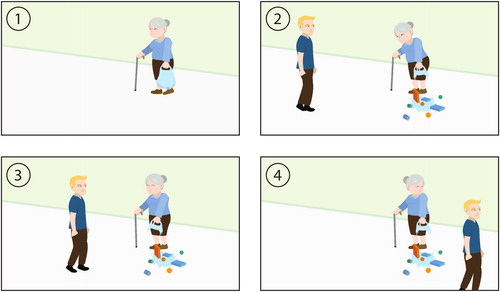

The ESCoT consists of eleven dynamic, cartoon-style social interactions (each approximately 30 seconds long): one practice interaction, five interactions involving social norm violations and five interactions without social norm violations. Participants watched the animated interaction on a computer screen and a static storyboard depicting a summarized version of the interaction was presented at the end. The storyboard remained on the screen during the subsequent questions for each interaction. Please see for an example interaction.

Participants were asked five questions after viewing each animation relating to: (1) general story comprehension; (2) cognitive ToM; (3) affective ToM; (4) interpersonal understanding of social norms; and (5) intrapersonal understanding of social norms. See and for further details.

Table 1. Description of the questions from the Edinburgh Social Cognition Test (ESCoT).

Table 2. Example scoring of the Edinburgh Social Cognition Test (ESCoT) taken from Scenario 1.

To allow participants to give their optimal interpretation of each interaction and capture the quality of their response, each participant was prompted once with the question, “Can you tell me more about what you mean by that?” or “Can you explain that in a little bit more detail?” Participants were prompted if they gave a limited response or their response lacked important information from the interaction. The general comprehension question was not scored as misinterpretations of the social interaction would become evident when participants answered the subsequent social cognition test questions. Participants were asked the social cognition test questions even if they misinterpreted the social interaction. Each question was awarded a maximum of 3 points, with a maximum score of 30 points for each social cognitive ability. The maximum total score was 120 points and the ESCoT took approximately 20–25 minutes to complete.

Participants

Nineteen adults (12 males, 7 females) aged 19–66 years (M = 38.47, SD = 15.63) with a diagnosis of Asperger’s Syndrome (AS) or High-Functioning Autism (HFA) according to established DSM-IV criteria (American Psychiatric Association [APA], Citation2000) were recruited from charities, support groups and from a research database (cf. according to DSM-V, they would all be diagnosed as Autism Spectrum Disorder). Participants confirmed their clinical diagnosis of ASD via official diagnosis letters which they received from their clinician. A comparison group of thirty-eight NC adults (23 males, 15 females) aged 19–67 years (M = 37.50, SD = 17.75) were recruited using online advertisement and through a research volunteer panel.

We used previously acquired data from 236 NC adults between the ages of 18 and 85 (some were included in this study as controls) to establish normative data and derive ESCoT cut-off scores for the subtests and total scores based on the lowest 5th percentile. These individuals were recruited through online advertisement and through a research volunteer panel. This included 147 younger adults (67 males, M age = 23.39, SD = 4.11, range = 18–35, M education = 16.90, SD = 2.20), 30 middle-aged adults (15 males, M = 50.60, SD = 5.77, range = 45–60, M education = 15.53, SD = 2.86) and 59 older adults (23 males, M = 72.44, SD = 6.05, range = 65–85, M education = 14.58, SD = 2.88). None of the NC adults had any self-reported history of neurological or psychiatric disorders based on the exclusion criteria from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-III) (Wechsler, Citation1997). Informed consent was obtained from all individuals and the study was approved by the local ethics committee.

The participants’ demographic information, ASD screening questionnaires and IQ scores are reported in .

Table 3. Demographics information of participants: Mean (SD).

Measures

Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence, Second Edition (WASI-II) (Wechsler, Citation2011): The WASI-II was administered as a measure of verbal comprehension and perceptual reasoning. Participants completed four subtests: Vocabulary; Similarities; Block Design; and Matrix Reasoning. The Vocabulary and Similarities subsets provided a Verbal Comprehension Index (VCI) and Block Design and Matrix Reasoning provided a Perceptual Reasoning Index (PRI) (McCrimmon & Smith, Citation2013; Wechsler, Citation2011).

Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ) (Baron-Cohen et al., Citation2001): This self-report questionnaire assesses whether individuals with a normal IQ possess traits related to the autism spectrum (maximum score = 50).

The Empathy Quotient (EQ) (Baron-Cohen & Wheelwright, Citation2004): The EQ measures the ability to identify and understand the thoughts and feelings of others and to respond to these with appropriate emotions (maximum score = 80).

The Systemizing Quotient (SQ) (Wheelwright et al., Citation2006): The SQ assesses the drive to analyze or construct systems such as mechanical systems (maximum score = 150).

The Reading the Mind in the Eyes (RME) (Baron-Cohen et al., Citation2001): Participants were presented with photographs of the eye region of human faces and selected a response from four adjectives which best described what the individual was thinking or feeling. Prior to performing the test, participants were provided with a glossary to clarify what each adjective meant, in case they were unsure or unfamiliar with the word. Participants were given unlimited time to respond (maximum score = 36). Higher scores indicated better performance.

The Reading the Mind in Films (RMF) (Golan et al., Citation2006): Participants viewed short scenes of varying durations involving social interactions from feature films and selected a response from four adjectives that best described what the protagonist was thinking or feeling at the end of the scene. Again, participants were provided with a glossary of the adjectives for clarification and responded verbally. There was no time limit for responses and participants could score a maximum of 22 with higher scores indicating better performance.

The Social Norms Questionnaire (SNQ) (Rankin, Citation2008): The SNQ was developed to screen patients for potential behavior changes and examines how well participants understand the social standards that govern their behavior in UK mainstream culture. Participants were given a list of behaviors (e.g. tell a stranger you don’t like their hairstyle?) and asked to indicate whether or not the behaviors were socially acceptable to perform in the presence of a stranger or acquaintance, not a close friend or family member (maximum score = 22). Higher scores indicated better performance. The SNQ also calculates the types of errors made by participants. An over-adherence error occurs when the statement is socially acceptable, but the participant disagrees with it. A rule-break error is when responses violate a social norm.

Procedure

Participants completed the measures in a single session, taking approximately two hours to complete. The ASD questionnaires were completed online. The order of the tasks was the same for each participant and regular breaks were provided.

Statistical analysis

Inter-rater reliability was assessed using intraclass correlations (ICC) for a random 10% of the sample using raters blind to the diagnosis of the groups. The analysed ESCoT data were age-adjusted based on the regression analyses published in Baksh et al. Citation(2018; see supplementary materials). Parametric and non-parametric analyses were conducted based on initial exploratory analyses (Shapiro-Wilk test, p > 0.05). Correlational analyses were conducted on all participants using Spearman’s rho correlational analyses to examine the relationship between the ESCoT and the established social cognition tests. To examine overall differences on the ESCoT subtests (cognitive ToM, affective ToM, inter- and intrapersonal understanding of social norms) and SNQ subtests (over-adherence and rule break), a Friedman Test was used. If this yielded a significant difference, follow-up analyses were conducted using independent samples and paired-samples t-tests for cognitive and affective ToM while Mann-Whitney U and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were performed for inter- and intrapersonal understanding of social norms and the SNQ subtests. An independent sample t-test was performed to examine mean group differences on the RME. Mann-Whitney U tests were performed on ESCoT total scores, RMF and SNQ total scores. The alpha values were set at p < 0.05 and the Holm correction to adjust for multiple comparisons was applied. Effect sizes using both partial eta squared (ηp2) and Cohen’s d (Cohen, Citation1988, Citation1992) were calculated.

The relationship between performance on all social cognition tests and the ASD screening questionnaires (AQ, EQ and SQ) were examined using an exploratory regression analysis. In the first stage, the background predictors (age, sex, years of education) which significantly correlated with the outcome variables (ESCoT total scores and established social cognition tests) at a pre-specified significance level of p < 0.20 were entered into the analysis (Altman, Citation1991) using the enter method. We chose a significance level of p < 0.20 over more traditional levels such as p < 0.05 since p < 0.05 can fail in identifying variables known to be important to the outcome variable and simulation studies have shown that a cut-off of p < 0.20 yields better outcomes (Bursac et al., Citation2008; Lee, Citation2014). VCI scores were included in the first stage of the regression analysis if VCI scores correlated with the outcome variables (ESCoT total score, RME, RMF and SNQ total scores) at p < 0.20. In the second stage, AQ, EQ and SQ scores were entered using the stepwise method (entry criterion p < 0.05, removal criterion p > 0.10). Finally, we conducted Area Under The Curve (AUC) and Receiver Operator Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis to examine the discriminative abilities of the ESCoT and established tests.

Results

Cut-off scores to detect abnormal performance on the ESCoT

Raw score age adjustments were applied (Baksh et al., Citation2018; see supplementary materials). ESCoT cut-off scores for the subtests and total scores were based on the lowest 5th percentile. Using the cut-offs, 6.77% of our 236 NC were impaired on the cognitive ToM subtest, 4.66% on affective ToM, 6.77% on interpersonal understanding of social norms and 6.77% on intrapersonal understanding of social norms. 5.50% of NC adults were impaired on ESCoT total score. shows the cut-offs for each subtest and ESCoT total scores.

Table 4. Cut-off scores for the Edinburgh Social Cognition Test (ESCoT) subtests and total score based on the 5th percentile.

Inter-rater reliability

Excellent inter-rater reliability (Cicchetti, Citation1994) was observed for all subtests of the ESCoT: cognitive ToM (ICC = 0.80), affective ToM (ICC = 0.97), interpersonal understanding of social norms (ICC = 0.96), intrapersonal understanding of social norms (ICC = 0.98) and the ESCoT total score (ICC = 0.97).

As shows the cognitive ToM subtest of the ESCoT significantly correlated with the RME, RMF and SNQ. The affective ToM subtest positively correlated with the RMF. Interpersonal understanding of social norms significantly correlated with the RME and RMF. Intrapersonal understanding of social norms significantly correlated with the RME.

Table 5. Correlations between the tests of social cognition.

ESCoT total scores significantly positively correlated with the RME, RMF and the SNQ. The RME test significantly correlated with the RMF and SNQ. Performance on the RMF positively correlated with performance on the SNQ.

ESCoT subtest correlations

Cognitive ToM significantly correlated with affective ToM and interpersonal understanding of social norms. While affective ToM positively correlated with interpersonal understanding of social norms, performance on interpersonal understanding of social norms correlated with performance on the intrapersonal understanding of social norms. Intrapersonal understanding of social norms did not significantly correlate with performance on cognitive ToM or affective ToM. All subtests significantly correlated with ESCoT total score.

Group comparisons between ASD adults and NC on ESCoT and established social cognition tests

A non-parametric Friedman test showed a statistically significant difference between the subtests of the ESCoT (χ2 (3) = 74.91, p < 0.001) for NC and ASD. Post-hoc analysis with Holm correction for multiple comparisons demonstrated performance was poorer on the cognitive than the affective ToM (t(56) = −7.17, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.20, d = 1.04). As shown in , ASD adults scored significantly lower than NC adults, on cognitive ToM (t(23.26) = −4.40, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.45, d = 1.82) and affective ToM (t(23.76) = −3.70, p < 0.01, ηp2 = 0.37, d = 1.52).

Table 6. Results by group for the Edinburgh Social Cognition Test (ESCoT) subtests: Mean (SD).

All participants performed poorer on inter- compared to intrapersonal understanding of social norms (Z = −6.31, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.70, d = 3.05). Furthermore a significant difference was found between groups, with the ASD group performing poorer than NC, on the interpersonal understanding of social norms (U = 140.50, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.25, d = 1.15) and intrapersonal understanding of social norms (U = 226.50 p < 0.05, ηp2 = 0.09, d = 0.64).

shows the group comparisons on the established social cognition tests and ESCoT total scores. Overall, performance on the ESCoT was significantly poorer for the ASD group than the NC group. Moreover, scores were significantly lower for the ASD group on the RME and RMF compared to NC. ASD adults performed poorer than NC on the SNQ total scores. There were no statistically significant differences between ASD adults and NC for the SNQ subtests (χ2(1) = 0 .49, p > 0.05).

Table 7. Results by group for the tests of social cognition: Mean (SD).

Post-hoc power analysis

While we reported large effect sizes (smallest Cohen’s d = 0.64), we were nevertheless interested in confirming that our analyses were not underpowered due to our sample size. Post hoc power analyses found power for the group comparisons to be excellent for all group comparisons (all power analyses between 0.94 and 1.00, alpha level = 0.05) with the exception of intrapersonal understanding of social norms (power = 0.59) and the SNQ (power = 0.71).

Relationship between social cognition tests, ASD screening questionnaires and IQ

The variables that correlated with ESCoT total scores at p < 0.20 were age (rs (57) = −0.19, p < 0.20), years of full-time education (rs (57) = 0.32, p < 0.20) and VCI scores (rs (55) = 0.39, p < 0.20). These were included in the regression analysis using the enter method in the first stage. None of the predictor variables correlated significantly with one another at p < 0.01 after years of full-time education was accounted for; therefore, the effect of suppressor variables was not examined. In the stepwise regression analysis for ESCoT total score, years of full-time education (β = 0.84, p < 0.05) and AQ scores (β = −0.62, p < 0.01) were retained in the model and accounted for a significant proportion of variance in ESCoT total scores (R2 = 0.61, F(4, 50) = 19.86, p < 0.001).

Only VCI significantly correlated with RME scores at p < 0.20 (rs (55) = 0.30, p < 0.20). This was included in the regression analysis using the enter method in the first stage. In the final model, VCI scores (β = 0.09, p < 0.05) and EQ scores (β = 0.14, p < 0.01) accounted for a significant proportion of variance in RME performance (R2 = 0.19, F(2, 52) = 6.20, p < 0.01).

For the RMF, participants’ sex (1 = male, 2 = female, rs (56) = 0.25, p < 0.20) and VCI scores (rs (54) = 0.45, p < 0.01) were included in the first stage of the analysis. In the final model, VCI scores (β = 0.10, p < 0.001) and AQ scores (β = −0.11, p < 0.01) were retained and accounted for a significant proportion of variance in RMF scores (R2 = 0.42, F(3, 50) = 12.15, p < 0.001).

Participants’ VCI scores were included in the first stage of the regression analysis for SNQ scores (rs (55) = 0.34, p < 0.20). In the final model, VCI scores (β = 0.06, p < 0.01), EQ scores (β = 0.06, p < 0.01) and SQ scores (β = 0.03, p < 0.05) accounted for a significant proportion of variance in SNQ scores (R2 = 0.32, F(3, 51) = 7.87, p < 0.001).

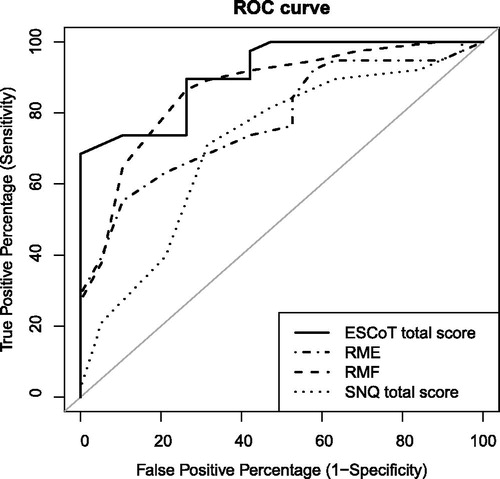

AUC and ROC analysis for the social cognition tests

The AUC values and 95% confidence intervals for the tests were: 0.91 (0.83–0.98) for the ESCoT total score, 0.77 (0.65–0.89) for the RME, 0.87 (0.77–0.97) for the RMF and 0.71 (0.57–0.86) for the SNQ total score. These results demonstrate that of the social cognition tests, the ESCoT is the most effective at distinguishing between the two groups.

shows a plot of the diagnostic value of the ESCoT compared to established tests of social cognition (RME, RMF and SNQ). Overall, the ESCoT showed the highest accuracy of the four tests.

Number of ASD and NC adults impaired on the ESCoT

Based on our cut-off scores, 36.84% of ASD adults were impaired on the cognitive ToM subtest compared to 0% of NC adults, and 26.31% were impaired on affective ToM compared to 0% of NC. On interpersonal understanding of social norms, 36.84% of the ASD group were impaired compared to 7.89% of the NC group. A total of 15.79% of adults with ASD were impaired on intrapersonal understanding of social norms compared to 5.26% of the NC adults. Finally, 42.11% of ASD adults were impaired on overall ESCoT scores compared to 0% of the NC adults.

Discussion

The ESCoT is a new test of social cognition that assesses cognitive ToM, affective ToM and inter- and intrapersonal understanding of social norms within the same test. We investigated the convergent validity of the ESCoT against traditional tests and compared performance of ASD adults to NC adults on these tests. Moreover, we examined the influence of intelligence and ASD diagnosis on the ESCoT and traditional tests of social cognition. The ESCoT showed good convergent validity with traditional social cognition tests. ASD adults performed poorer on all subtests of the ESCoT and traditional tests compared with NC. Regression results showed that better overall performance on the ESCoT was predicted by more years of education and lower AQ scores. ESCoT total score was not predicted by VCI or PRI; this contrasts with performance on the traditional social cognition tests included in this study. Higher VCI scores predicted better performance on the RME, higher VCI and EQ scores predicted better performance on the RMF while higher VCI, EQ and SQ scores predicted better performance on the SNQ. The ESCoT showed very good discriminative value, followed by the RMF, the RME and the SNQ. Overall, the ESCoT showed the highest accuracy compared to the RME and SNQ. A total of 42.11% of ASD adults were impaired on the ESCoT total score compared to 0% NC.

Significant associations between the ESCoT and traditional social cognition tests provide evidence of convergent validity for the ESCoT as a test of social cognition (see supplementary materials for scatterplots and correlations divided by group). The cognitive ToM subtest of the ESCoT positively correlated with the RME. There is currently debate relating to what the RME assesses and some authors have argued that the RME is a test of emotion recognition (Oakley et al., Citation2016). While it could be argued that the RME is an affective ToM measure (Duval et al., Citation2011), our findings suggest that it relates to cognitive components of ToM. Indeed, the RME asks participants to infer what the person is thinking or feeling. Intrapersonal understanding of social norms did not correlate with cognitive and affective ToM of the ESCoT but was positively correlated with the RME. Furthermore, the RME correlated with our measure of empathy. It may be that the RME is related to several aspects of social cognition. The positive correlations between ESCoT subtests (particularly cognitive and affective ToM) suggests that performance on one ability is associated with performance on other abilities, but still show differentiation in performance in that they are predicted by different but overlapping constructs. Performance on cognitive ToM was predicted by age, but performance on affective ToM was predicted by age and sex (Baksh et al., Citation2018). These findings show that while cognitive and affective ToM are distinct, they do overlap (Kalbe et al., Citation2010; Sebastian et al., Citation2011; Shamay-Tsoory et al., Citation2010), and both should be considered when assessing ToM.

Poorer performance of ASD adults compared to NC on cognitive ToM, affective ToM and interpersonal understanding of social norms supports previous findings (Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright, Hill, et al., Citation2001; Castelli et al., Citation2002; Golan et al., Citation2006; Murray et al., Citation2017; Thiébaut et al., Citation2016; Zalla et al., Citation2009). Although the ESCoT showed good sensitivity on all subtests, the finding that ASD adults showed impaired intrapersonal understanding of social norm is somewhat in contrast to our prediction and previous findings of intact performance (Baez et al., Citation2012; Gleichgerrcht et al., Citation2013). Our findings show that ASD adults have difficulties with how they should behave in social interactions. However, it is possible that the ASD group had difficulties in processing the wider context of the interaction, due to difficulties in weak central coherence (the inability to understand context) (Frith, Citation1989, Citation2003). In this study, individuals with ASD generally knew when a social norm had been violated and responded appropriately to the yes/no aspect of the question. Yet, in general, participants with ASD gave egocentric responses (e.g., I’m a nice person) regarding why they would/would not have behaved as the character in the animation, instead of referencing the wider context of the interaction (e.g., they needed help, helping others is the right thing to do) to explain why they would have behaved in a particular way.

A major advantage of the ESCoT over existing tests is the magnitude of the reported effects. Our effects sizes for the group differences on cognitive and affective ToM is greater than those on the RME and RMF. Increased ecological validity may explain the greater effect sizes found for the ESCoT compared to the RME, which lacks important contextual information, and the RMF, which uses pre-existing stimuli that are overdramatized (Murray et al., Citation2017). With the ESCoT, we have shown that contextually driven tests more clearly demonstrate group differences between ASD and NC. Performance on the ESCoT may be more representative of the everyday difficulties faced by ASD adults compared to NC. There are several other advantages of the ESCoT over existing tests in the social cognition literature. Firstly, unlike tests such as the TASIT, the ESCoT is a short and detailed test of social cognition with self-contained interactions. The ESCoT also provides researchers and clinicians with two subtests of ToM and social norm understanding.

All participants performed better on affective ToM, compared to cognitive ToM, which is similar to previous findings (Bottiroli et al., Citation2016; Shamay-Tsoory et al., Citation2007). Participants were better on intrapersonal understanding of social norms compared to interpersonal understanding. While other studies may find differential performance on social cognitive abilities using different tests, these tests are not matched for difficulty. Matching social cognition components for equivalent difficulty is challenging to achieve. Future studies in individuals with ASD could examine ways of controlling for level of difficulty between subtests. Similar to previous findings (Murray et al., Citation2017), we found that poorer performance on the ESCoT in the ASD group could not be explained by general cognitive abilities while performance on the traditional tests was predicted by VCI and PRI, similar to earlier work (Baker et al., Citation2014; Golan et al., Citation2006; Kaland et al., Citation2002; McDonald et al., Citation2003). This is an advantage for the ESCoT as it can be used in clinical populations who may show some impairment but still have intact verbal abilities. Moreover, our NC group did not perform at ceiling on the test. The variability of performance in the control group is maybe useful for detecting individual differences in nonclinical populations. Further usefulness of the ESCoT is its superior diagnostic value, compared to other social cognition tests, with an AUC value of 0.91.

A limitation of this study is the small sample size for the ASD group. However, the large effects sizes (e.g., Cohens d = 1.79) and post hoc power analyses for the ESCoT indicate that, even with a small sample size of ASD adults, we were able to detect meaningful group differences. Further is the lack of formal diagnostic information relating to symptom level data regarding our ASD participants. Moreover, there were too few females to examine whether there were sex differences on the ESCoT. ASD is a heterogeneous condition (Ghaziuddin & Mountain-Kimchi, Citation2004), and given our wide age range and the changes in diagnostic criteria for ASD over the past 60 years, heterogeneity is more likely in our sample. It is also unknown whether our participants’ diagnoses were made close to the time of study inclusion. Recent research suggests that ASD symptoms improve in adulthood (Woodman et al., Citation2015), although other studies suggest that core symptoms of ASD tend to persist and there are few changes in adults over the lifetime (Beadle-Brown et al., Citation2006; Matson & Horovitz, Citation2010). Future work should examine the relationship between ASD diagnosis, age of diagnosis, ASD symptoms and ESCoT performance. In our findings, we found that a total of 42.11% of ASD adults were impaired on the ESCoT total score (but still substantially higher than the 0% of NC adults). Overall, ASD individuals performed poorer than NC, but individually, there was heterogeneity with the ASD group on the ESCoT. Further work is needed to identify how scores on the ESCoT vary with ASD symptomology. While the groups were not matched on verbal comprehension scores, in our NC group, verbal comprehension was not a predictor of ESCoT performance. Moreover, ASD participants were within the normal IQ range (full-scale IQ > 70) therefore, future studies would benefit from including lower functioning individuals to examine if the ESCoT may be useful in this sample of individuals. Finally, the smaller group difference in intrapersonal understanding of social norms compared to the other ESCoT subtests and the limited correlations with other tests perhaps indicates that this subtest may not be performing as well as cognitive ToM, affective ToM and interpersonal understanding of social norms. However, few studies have examined intrapersonal understanding of social norms in social cognition research. Therefore, future research should validate this subtest against behaviour to understand this social cognitive ability and how it relates to other domains.

Conclusion

We found that adults with ASD perform poorer than NC on cognitive ToM, affective ToM and inter- and intrapersonal understanding of social norms. These impairments may be responsible for the difficulties frequently observed in social interactions. The convergent validity between the ESCoT and established tests of social cognition show that the ESCoT is a sensitive test of social cognition in ASD adults. We showed that the ESCoT can detect large effects with a restricted sample size and shows better diagnostic accuracy than established tests. Many of the current tests of social cognition have limited use in clinical settings (Dodich et al., Citation2015) but we have demonstrated that the ESCoT may be a useful test to assess patients and aid in the detection of potential difficulties in ToM and social norm understanding.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Molly Nelson and Helen Stocks for conducting the inter-rater reliability.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, RAB, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adolphs, R. (2009). The social brain: Neural basis of social knowledge. Annual Review of Psychology, 60(1), 693–716. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163514

- Altman, D. G. (1991). Practical statistics for medical research. Chapman and Hall.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4 ed.)

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) (5th ed.)

- Baez, S., García, A. M., & Ibanez, A. (2016). The social context network model in psychiatric and neurological diseases. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences, 30, 379–396.

- Baez, S., Herrera, E., Villarin, L., Theil, D., Gonzalez-Gadea, M. L., Gomez, P., Mosquera, M., Huepe, D., Strejilevich, S., Vigliecca, N. S., Matthäus, F., Decety, J., Manes, F., & Ibañez, A. M. (2013). Contextual social cognition impairments in Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder. PLOS One., 8(3), e57664. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0057664

- Baez, S., Rattazzi, A., Gonzalez-Gadea, M. L., Torralva, T., Vigliecca, N. S., Decety, J., Manes, F., & Ibanez, A. (2012). Integrating intention and context: Assessing social cognition in adults with Asperger Syndrome. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6, 1–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2012.00302

- Baker, C. A., Peterson, E., Pulos, S., & Kirkland, R. A. (2014). Eyes and IQ: A meta-analysis of the relationship between intelligence and “Reading the Mind in the Eyes. Intelligence, 44, 78–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2014.03.001

- Baksh, R. A., Abrahams, S., Auyeung, B., & MacPherson, S. E. (2018). The Edinburgh Social Cognition Test (ESCoT): Examining the effects of age on a new measure of theory of mind and social norm understanding. Plos One, 13(4), e0195818. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195818

- Baron-Cohen, S., & Wheelwright, S. (2004). The empathy quotient: An investigation of adults with Asperger Syndrome or High Functioning Autism and normal sex differences. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34(2), 163–175. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15162935 doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JADD.0000022607.19833.00

- Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Hill, J., Raste, Y., & Plumb, I. (2001). The “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” test revised version: a study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied disciplianes 42(2), 241–251.

- Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Skinner, R., Martin, J., & Clubley, E. (2001). The Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ): Evidence from asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31(1), 5–17. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11439754

- Beadle-Brown, J., Murphy, G., & Wing, L. (2006). The Camberwell cohort 25 years on: Characteristics and changes in skills over time. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 19(4), 317–329. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2006.00289.x

- Bottiroli, S., Cavallini, E., Ceccato, I., Vecchi, T., & Lecce, S. (2016). Theory of mind in aging: Comparing cognitive and affective components in the faux pas test. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 62, 152–162. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2015.09.009

- Bursac, Z., Gauss, C. H., Williams, D. K., & Hosmer, D. W. (2008). Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code for Biology and Medicine, 3(1), 17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1751-0473-3-17

- Castelli, F., Frith, C., Happé, F., & Frith, U. (2002). Autism, Asperger syndrome and brain mechanisms for the attribution of mental states to animated shapes. Brain, 125(8), 1839–1849. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awf189

- Cicchetti, D. V. (1994). Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment, 6(4), 284–290. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.6.4.284

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Earlbaum Associates. 20–26.

- Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155

- Couture, S., Penn, D., Losh, M., Adolphs, R., Hurley, R., & Piven, J. (2010). Comparison of social cognitive functioning in schizophrenia and high functioning autism: more convergence than divergence. Psychological Medicine, 40(4), 569–579. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329170999078X

- Dodich, A., Cerami, C., Canessa, N., Crespi, C., Iannaccone, S., Marcone, A., Realmuto, S., Lettieri, G., Perani, D., & Cappa, S. F. (2015). A novel task assessing intention and emotion attribution: Italian standardization and normative data of the Story-based Empathy Task. Neurological Sciences, 36(10), 1907–1912. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-015-2281-3

- Duval, C., Piolino, P., Bejanin, A., Eustache, F., & Desgranges, B. (2011). Age effects on different components of theory of mind. Consciousness and Cognition, 20(3), 627–642. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2010.10.025

- Dziobek, I., Fleck, S., Kalbe, E., Rogers, K., Hassenstab, J., Brand, M., Kessler, J., Woike, J. K., Wolf, O. T., & Convit, A. (2006). Introducing MASC: a movie for the assessment of social cognition. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36(5), 623–636. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0107-0

- Frith, U. (1989). Autism: Explaining the Enigma. Blackwell.

- Frith, U. (2003). Autism: Explaining the Enigma. (2nd ed.) Wiley.

- Frith, U. (2004). Emanuel Miller lecture: Confusions and controversies about Asperger syndrome. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(4), 672–686. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/store/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00262.x/asset/j.1469-7610.2004.00262.x.pdf?v=1&t=iu6ui52r&s=43fc30dca628ccc9faca8d56f35095bda591706a

- Ghaziuddin, M., & Mountain-Kimchi, K. (2004). Defining the intellectual profile of Asperger syndrome: Comparison with high-functioning autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34(3), 279–284. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JADD.0000029550.19098.77

- Gleichgerrcht, E., Torralva, T., Rattazzi, A., Marenco, V., Roca, M., & Manes, F. (2013). Selective impairment of cognitive empathy for moral judgment in adults with high functioning autism. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 8(7), 780–788. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nss067

- Golan, O., Baron-Cohen, S., Hill, J. J., & Golan, Y. (2006). The “reading the mind in films” task: complex emotion recognition in adults with and without autism spectrum conditions. Social Neuroscience, 1(2), 111–123. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17470910600980986

- Happé, F. G. (1994). An advanced test of theory of mind: Understanding of story characters’ thoughts and feelings by able autistic, mentally handicapped, and normal children and adults. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 24(2), 129–154. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02172093

- Heavey, L., Phillips, W., Baron-Cohen, S., & Rutter, M. (2000). The Awkward Moments Test: A naturalistic measure of social understanding in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30(3), 225–236.

- Henry, J. D., Cowan, D. G., Lee, T., & Sachdev, P. S. (2015). Recent trends in testing social cognition. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 28(2), 133–140. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000139

- Izuma, K., Matsumoto, K., Camerer, C. F., & Adolphs, R. (2011). Insensitivity to social reputation in autism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(42), 17302–17307. doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1107038108

- Jolliffe, T., & Baron-Cohen, S. (1999). A test of central coherence theory: linguistic processing in high-functioning adults with autism or Asperger syndrome: is local coherence impaired? Cognition, 71(2), 149–185. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-0277(99)00022-0

- Kaland, N., Møller‐Nielsen, A., Callesen, K., Mortensen, E. L., Gottlieb, D., & Smith, L. (2002). A new advanced ‘test of theory of mind: evidence from children and adolescents with Asperger syndrome. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 43(4), 517–528. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00042

- Kalbe, E., Schlegel, M., Sack, A. T., Nowak, D. A., Dafotakis, M., Bangard, C., Brand, M., Shamay-Tsoory, S., Onur, O. A., & Kessler, J. (2010). Dissociating cognitive from affective theory of mind: a TMS study. Cortex, 46(6), 769–780. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2009.07.010

- Klin, A. (2000). Attributing social meaning to ambiguous visual stimuli in higher‐functioning autism and Asperger syndrome: the social attribution task. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 41(7), 831–846. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00671

- Lee, P. H. (2014). Should we adjust for a confounder if empirical and theoretical criteria yield contradictory results? A simulation study. Scientific Reports, 4(1), 6085. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/srep06085

- Lehnhardt, F., Gawronski, A., Volpert, K., Schilbach, L., Tepest, R., Huff, W., & Vogeley, K. (2011). Autism spectrum disorders in adulthood: clinical and neuropsychological findings of Aspergers syndrome diagnosed late in life. Fortschritte Der Neurologie · Psychiatrie, 79(5), 290–297. doi:https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1273233

- Lugnegård, T., Hallerbäck, M. U., Hjärthag, F., & Gillberg, C. (2013). Social cognition impairments in Asperger syndrome and schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research, 143(2), 277–284. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2012.12.001

- Mathersul, D., McDonald, S., & Rushby, J. A. (2013). Understanding advanced theory of mind and empathy in high-functioning adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 35(6), 655–668. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13803395.2013.809700

- Matson, J. L., & Horovitz, M. (2010). Stability of autism spectrum disorders symptoms over time. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 22(4), 331–342. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-010-9188-y

- McCrimmon, A. W., & Smith, A. D. (2013). Test Review: Review of the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence, Second Edition (WASI-II). Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 31(3), 337–341. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282912467756

- McDonald, S., Flanagan, S., Rollins, J., & Kinch, J. (2003). TASIT: A new clinical tool for assessing social perception after traumatic brain injury. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 18(3), 219–238. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/00001199-200305000-00001

- Murray, K., Johnston, K., Cunnane, H., Kerr, C., Spain, D., Gillan, N., Hammond, N., Murphy, D., & Happé, F. (2017). A new test of advanced theory of mind: The “Strange Stories Film Task” captures social processing differences in adults with autism spectrum disorders. Autism Research, 10(6), 1120–1132. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1744

- Oakley, B. F., Brewer, R., Bird, G., & Catmur, C. (2016). Theory of mind is not theory of emotion: A cautionary note on the Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125(6), 818. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000182

- Palmen, A., Didden, R., & Lang, R. (2012). A systematic review of behavioral intervention research on adaptive skill building in high-functioning young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(2), 602–617. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2011.10.001

- Rankin, K. P. (2008). Social Norms Questionaire NINDS Domain Specific Tasks of Executive Function, NINDS.

- Roeyers, H., Buysse, A., Ponnet, K., & Pichal, B. (2001). Advancing advanced mind‐reading tests: empathic accuracy in adults with a pervasive developmental disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 42(2), 271–278. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00718

- Scheeren, A. M., de Rosnay, M., Koot, H. M., & Begeer, S. (2013). Rethinking theory of mind in high‐functioning autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54(6), 628–635. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12007

- Schilbach, L., Eickhoff, S. B., Cieslik, E. C., Kuzmanovic, B., & Vogeley, K. (2012). Shall we do this together? Social gaze influences action control in a comparison group, but not in individuals with high-functioning autism. Autism, 16(2), 151–162. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361311409258

- Sebastian, C. L., Fontaine, N. M., Bird, G., Blakemore, S.-J., De Brito, S. A., McCrory, E. J., & Viding, E. (2011). Neural processing associated with cognitive and affective Theory of Mind in adolescents and adults. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 7(1), 53–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsr023

- Senju, A., Southgate, V., White, S., & Frith, U. (2009). Mindblind eyes: an absence of spontaneous theory of mind in Asperger syndrome. Science, 325(5942), 883–885. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1176170

- Shamay-Tsoory, S. G., Harari, H., Aharon-Peretz, J., & Levkovitz, Y. (2010). The role of the orbitofrontal cortex in affective theory of mind deficits in criminal offenders with psychopathic tendencies. Cortex, 46(5), 668–677. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2009.04.008

- Shamay-Tsoory, S. G., Shur, S., Barcai-Goodman, L., Medlovich, S., Harari, H., & Levkovitz, Y. (2007). Dissociation of cognitive from affective components of theory of mind in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research, 149(1-3), 11–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2005.10.018

- Thiébaut, F. I., White, S. J., Walsh, A., Klargaard, S. K., Wu, H.-C., Rees, G., & Burgess, P. W. (2016). Does faux pas detection in adult autism reflect differences in social cognition or decision-making abilities? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(1), 103–112. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2551-1

- Van Overwalle, F. (2009). Social cognition and the brain: A meta‐analysis. Human Brain Mapping, 30(3), 829–858. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.20547

- Wechsler, D. (1997). Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale: Technical and interpretive manual (3rd ed.). The Psychological Corporation.

- Wechsler, D. (2011). Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence–Second Edition (WASI-II). NCS Pearson.

- Wheelwright, S., Baron-Cohen, S., Goldenfeld, N., Delaney, J., Fine, D., Smith, R., Weil, L., & Wakabayashi, A. (2006). Predicting autism spectrum quotient (AQ) from the systemizing quotient-revised (SQ-R) and empathy quotient (EQ). Brain Research, 1079(1), 47–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2006.01.012

- White, S., Hill, E., Happé, F., & Frith, U. (2009). Revisiting the strange stories: revealing mentalizing impairments in autism. Child Development, 80(4), 1097–1117. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01319.x

- Woodman, A. C., Smith, L. E., Greenberg, J. S., & Mailick, M. R. (2015). Change in autism symptoms and maladaptive behaviors in adolescence and adulthood: The role of positive family processes. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(1), 111–126. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2199-2

- Zalla, T., Sav, A.-M., Stopin, A., Ahade, S., & Leboyer, M. (2009). Faux pas detection and intentional action in Asperger Syndrome. A replication on a French sample. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39(2), 373–382. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-008-0634-y