1. The question of asymmetry

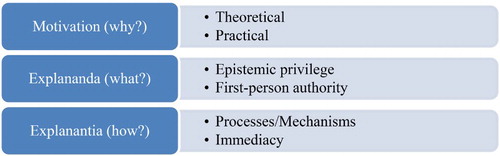

To ask what is special about self-knowledge is to ask how self-knowledge is different from other kinds of knowledge. More specifically, it is to ask how self-knowledge differs from our knowledge of the minds of other people. This is the topic of this issue. There are at least two possible motivations for focussing on the asymmetries between these two forms of knowledge. One might, for instance, be interested in epistemology generally, and knowledge of mental states specifically, and be drawn into the debate of self-knowledge to get clearer on the different (or similar) ways in which beliefs, desires, emotions, pains and so on can be known by a subject. To take this route is to have an intrinsic interest in some of the special features of self-knowledge. Consider, for instance, Christopher Peacocke (Citation1998), who begins an article on the topic by asking what is involved in the consciousness of an occurrent propositional attitude, and goes on to say: “I hope the intrinsic interest of these questions provides sufficient motivation to allow me to start by addressing them” (Citation1998, 63). Alternatively, one might want to explore self-knowledge in order to get a better understanding of some of our prudential and/or moral practices and concerns. Self-knowledge, on this view, is not interesting in and of itself, but rather deserves our interest because of something else (Cassam Citation2014).

At first blush, philosophers in the debate on self-knowledge, whatever their motivation, all seem interested in the same phenomenon, and hence appear to address the very same question, formulated in different ways. And in a sense they do, in so far as the question is a general one of what distinguishes self-knowledge from other kinds of knowledge. We might call this “the question of asymmetry”.

We can learn a great deal from seeing these philosophers as being in some sense engaged in the same project, but only “in some sense”, for the explanandum of “asymmetry” is not unambiguous – there are, in fact, a variety of asymmetries at stake, which call out for different explanations. The literature on self-knowledge is diverse, and the current issue is no exception.

We first of all need to distinguish between the claim that we are epistemically privileged with respect to our own states and the claim that we have first-person authority over them. The distinction is subtle but important. Being epistemically privileged means that our second-order beliefs about our first-order states are more likely to result in knowledge, compared, for instance, to the way in which we gain knowledge of others’ mental states or the external world (sometimes also referred to as “first-person privilege” or “privileged access” (see, e.g. Byrne Citation2005)). First-person authority, on the other hand, means, in most general terms, that the speaker herself is the “authority” on what state she thinks (or says) she is in. More specifically, in the context of self-knowledge, first-person authority refers to the special authority subjects have with respect to expressing or reporting their own (current) mental lives.

It is important to realize that epistemic privilege and first-person authority are two different explananda, each allowing, in principle, for different explanations. Roughly, the first question concerns the epistemology of our self-reports – what makes these items particularly knowledgeable? – whereas the second concerns the question of what underlies our practice of taking each other at our words. What makes these items particularly resistant to challenge and correction, and why are they ordinarily presumed to be true?

The notions of epistemic privilege and first-person authority often collapse into each other. This is due, in part, to a rather specific conception of first-person authority, according to which knowledge of one's occurrent states is necessary and sufficient for first-person authority. Given that you generally know your own mental states, then surely that is the reason why other people do not question your sincere self-reports. So on this line of thinking, once we have explained epistemic privilege, we get first-person authority “for free”.

But this “reductionist” model is not the only option. At least one way of looking at some of the developments in the debate is by considering the so-called non-epistemic and, in most cases, practically motivated approaches to self-knowledge (e.g. rationalism, neo-expressivism and constitutivism), as advocating a more substantial conception of first-person authority and denying the implicit, gratuitous move from the epistemically to the practically and/or pragmatically significant.Footnote1 On this approach, first-person authority does not simply follow from the fact that our self-reports are more likely to yield knowledge, but requires further explanation. This approach would involve advocating an independence model with respect to epistemic privilege and first-person authority: one may explain the former without having explained the latter, and vice versa.

The idea that something would be missing even if we were to have explained the entire “epistemic” side of the asymmetry question is a central theme of Moran's writings on self-knowledge. Moran, for instance, considers someone with the capacity for a kind of “self-telepathy”, someone who has complete information, complete accuracy and complete reliability about her own mental states (Citation2001, 91). But according to Moran, even if some such capacity for self-telepathy were to exist (even if the person knew about his or her states “with immediacy, in a way that does not depend on any external ‘medium', and which involves no inference from anything else”), something would be missing. On Moran's view, what is missing is an agential attitude of endorsement or commitment: “the authority of the person to make up his mind, change his mind, endorse some attitude or disavow it” (Citation2001, 92). To take each other at our words involves, on this line of reasoning, that we first of all see each other as agents (see also McGeer Citation1996; McGeer Citation2015).Footnote2

The neo-expressivist proposal (Bar-On Citation2004, see also Bar-On Citation2015) is quite different, but shares some of the same methodological worries. Bar-On, more than anyone else in the debate, has teased apart some of the different questions that a philosopher might tackle when considering the general question of what is special about people's relation to their own minds. The central question for neo-expressivism concerns first-person authority: what explains the fact that our sincere self-reports (or avowals) “are so rarely questioned or corrected, are generally so resistant to ordinary epistemic assessments, and are so strongly presumed to be true” (Bar-On Citation2004, 11)? Bar-On is at pains to show that it is a further question whether and how avowals are items of self-knowledge, and a further question still what, avowals aside, explains self-knowledge. The implication is that an account of epistemic privilege and an account of (substantial) first-person authority may, in principle, come apart.

There is one further option with respect to the two explananda. Rather than defending a relation of dependence or independence between the two, one could claim that the two coincide. It is possible to say that epistemic privilege explains the authority of avowals, whilst resisting the view according to which avowals are the result of standing in some epistemically privileged relation to one's own mental states. Rather, one might say that epistemic privilege is to be explained in the very act of expressing or avowing (see Roessler Citation2013 see also Roessler this issue).Footnote3

The question of which approach to adopt with regard to the two explananda is strongly influenced by one's conception of self-knowledge, either as something that one can possess independently of our articulated self-ascriptions or avowals (in speech or in thought), or as something that cannot be intelligibly understood independently of these avowing modes of self-articulation. Only on the former view are avowals understood as merely optional ways of articulating this knowledge.

These different frameworks of thinking about self-knowledge bring us back to the two motivations – theoretical or practical – mentioned earlier. Philosophers who have an “intrinsic” interest in some of the special features of self-knowledge typically also think that self-knowledge happens irrespectively of our broader communicative practices which centrally involve avowals, whereas those whose motivations are practical typically understand self-knowledge as having its roots in some of our socio-linguistic practices and capacities. This might just be a contingent fact that tells us very little, but it might also have some methodological value, for instance, of showing where, exactly, some of the (in)compatibilities between different approaches to self-knowledge are located.

2. Explaining the asymmetry

2.1. Special method

By far the most influential strategy for explaining epistemic privilege is to say that in the normal case, our knowledge of our first-order states is acquired in a special way, that we have what Alex Byrne calls “peculiar access” to our mental states. Peculiar access can, on its turn, be cached out in at least two ways: one pertaining to psychological processes or mechanisms involved and another to immediacy.

The first is a roughly psychological approach to explaining epistemic privilege, and is usually captured when philosophers talk of “introspection”: a special mechanism, module or faculty devoted exclusively to acquiring beliefs about our own first-order states. Introspection is often taken to involve a kind of “inner perception”, suggesting that there be an internal searchlight that shines its special light on the mental items in our consciousness. Alternatively, introspection may be described, as Armstrong (Citation1968) does, as “a self-scanning process in the brain” which does not involve a special organ of any kind (analogous to eyes in normal perception), but merely involves “the getting of beliefs”.

Another view that similarly aims to give a psychological explanation of epistemic privilege can be found, for instance, in Nichols and Stich (Citation2003), who postulate a “Monitoring Mechanism (MM) (or perhaps a set of mechanisms) that, when activated, takes the representation p in the Belief Box as input and produces the representation I believe that p as output” (Citation2003, 160, emphases in original). Armstrong as well as Nichols and Stich thus see the differences between knowledge of our own minds and knowledge of the minds of others as a psychological difference regarding the aetiology of self-attribution.

It is also possible to deny epistemic privilege on psychological grounds. Ryle's work on self-knowledge can be read in this way. Famously, he writes that “The sorts of things that I can find out about myself are the same as the sorts of things that I can find out about other people, and the methods of finding them out are much the same” (Ryle Citation1949, 138). Ryle even suggests that sometimes it is easier for someone to find out what they want to know about someone else than it is to find out about these things in the first-person case, but also grants that “in certain other important respects it is harder” (Citation1949, 138). Though it is difficult to assess whether Ryle genuinely rejects epistemic privilege, he is explicit about the fact that a denial of special, introspective mechanism forms no threat to what has just been referred to as first-person authority. In an exceptionally insightful section, titled “Disclosure by unstudied talk”, Ryle gives a detailed analysis of our practices of spontaneous expression, and considers what we can learn from those practices with respect to self-knowledge. He notes that if one were to avow being in pain, it would be “glaringly inappropriate” to respond with “do you?” or “how do you know?” (Citation1949, 164). This is because avowals are not “used to convey information, but to make a request or demand”, and, for instance, to express a desire by saying “I want” is “no more meant as a contribution to general knowledge than ‘please’” (Citation1949, 164). For Ryle, then, there not being any special mechanisms appears to be perfectly compatible with having reasons not to challenge or correct people they offer sincere self-ascriptions.

A number of contributors to this issue take up the question of whether a similar compatibility might not also apply to more recent interpretationist or inferentialist accounts (e.g. Carruthers Citation2009, Citation2011; Cassam Citation2014), thereby teasing out some of the possible levels at which the asymmetry between knowledge of self and other might operate.

2.2. Immediacy

A different way of filling in the explanation of the special or “peculiar” character of self-knowledge is by defending some version of the “immediacy thesis”.Footnote4 Usually, “immediacy” is defined by saying that self-knowledge is non-inferential, meaning that it is not based on evidence (of any kind, or just behavioural evidence). The immediacy thesis is sometimes also presented as the claim that self-knowledge is groundless, baseless, transparent or direct.

Importantly, immediacy is usually taken to explain both epistemic privilege and first-person authority. The ambition is to explain, via the notion of immediacy, not only what makes our second-order beliefs especially knowledgeable but also what makes them so authoritative. In other words, immediacy is intended to legitimize the move from the peculiar epistemic features of self-knowledge to the more practical or commonsensical practice of first-person authority. Thus, when person A sincerely reports that she feels drowsy, person B takes her at her word because person A is not basing her self-report on any kind of evidence.

The trouble is that “immediacy” is not an unambiguous notion. It is used to refer to different things (see also Cassam Citation2011, Citation2014). When discussing immediacy, some philosophers appear to be making primarily a phenomenological claim: from the avower's point of view, offering a self-report does not seem like an activity which involves reasoning, interpreting, detecting and so on. Avowals appear to us to be made on no basis at all. Usually, claims concerning the phenomenological immediacy of self-knowledge come together with claims concerning the effortlessness of self-ascriptions and/or avowals. Believing that you currently have a desire for coffee, or that you are sitting behind a computer does not take much energy, compared to, say, coming to believe that the sum of 24 × 25 equals 600 or that you harbour certain implicit biases.

Phenomenological immediacy is, in principle, compatible with the claim that our self-ascriptions are nonetheless inferential, psychologically speaking. This may be illustrated by looking at the debate of folk psychology, where proponents of mindreading accounts are typically not too impressed by phenomenological considerations as telling us anything about what underlies social cognition. For instance, Shannon Spaulding notes: “much of mindreading is supposed to be non-conscious, at the sub-personal level, and phenomenology cannot tell us what is happening at the sub-personal level” (Spaulding Citation2010, 129). Thus, for our self-ascriptions or avowals to be psychologically “immediate”, they should not just appear to us as non-inferential, but they should actually be non-inferential; furthermore, they should be non-inferential on both the personal and the sub-personal level.Footnote5

Finally, it is important to distinguish the psychological immediacy thesis from the epistemological immediacy thesis: self-knowledge is immediate in the epistemological sense if and only if the justification for your belief is non-inferential, that is, does not come from your having justification to believe other propositions (Pryor Citation2005; Cassam Citation2009, Citation2014; McDowell Citation2010). Psychological immediacy thus involves a claim about the process by which one's knowledge was acquired, whereas epistemic immediacy concerns the credentials or status of one's belief.Footnote6 To say that our avowals are epistemically immediate, then, involves the claim that inferences cannot (or do not) play a justifying role.

The distinction can be observed by recognizing the fact, suggested by McDowell (Citation1998), in response to Crispin Wright, that when someone's (self-)report is psychologically non-inferential, one is usually “not open to request for reasons or corroborating evidence”, whereas when a report is epistemically non-inferential or baseless, one is not open to (or cannot answer) the question “How do you know?” or “How can you tell?”. On the basis of these considerations, McDowell observes that observational knowledge is “indeed non-inferential” but “precisely not baseless” (1998, 48), since in such cases one can perfectly well answer such questions by saying that one is in a “position to see”.

Whether or not self-knowledge is either psychologically or epistemologically non-inferential, both or neither, it will be helpful to carefully indicate what type of immediacy thesis exactly is at issue.

2.3. This issue

The papers in this issue can be divided roughly into four themes: (1) those that focus on first-person authority, and/or the implications of the account thereof for epistemic privilege, (2) papers that focus on the (in)compatibility between different approaches to epistemic asymmetry and first-person authority, (3) those that address the scope of self-knowledge and the question of what the implications are of addressing the scope for specific approaches to self-knowledge and (4) papers that are methodologically oriented and ask what can we learn from self-knowledge by taking a closer look at our practices and capacities for knowing the minds of others.

2.3.1. First-person authority and epistemic privilege

Bar-On begins her article by calling attention to a prevalent presupposition in the current debate. The presupposition is that “the only way to vindicate first-person authority as understood by our folk-psychology is to identify specific ‘good-making’ epistemic features that render avowals especially knowledgeable” (Bar-On this issue). With this in mind, Bar-On goes on to evaluate recent attempts to capture first-person authority – Matthew Boyle's and Alex Byrne's, specifically – by appealing to the so-called transparency of mental self-attributions. Both approaches, Bar-On argues, face difficulties due in part to the aforementioned presupposition. Once we free ourselves of the presupposition, Bar-On argues, we may revise our understanding of the epistemic significance of transparent self-attributions, and recognize that not only beliefs can be transparent in this way, but that we can generally also tell whether we want x or are annoyed at y or perceive z by directly considering the intentional contents of the relevant states. Bar-On goes on to discuss and elaborate on what Sellars calls the “avowal role” of our self-reports and provides a novel approach to how transparency is to be explained on the neo-expressivist view. On the proposed view, the transparency of self-attributions of belief falls out as a consequence of the expressive transparency of avowals generally, and in particular the fact that avowals are instances of directly giving voice to the avower's state of mind, thereby allowing others to “see through” them. She ends her article by considering some of the reasons for thinking that neo-expressivism is better suited for integration with a folk-psychologically-grounded understanding of ourselves than the alternatives.

In the second paper of this issue, Johannes Roessler argues that the expressive aspect of self-ascriptions of belief holds the key to making intelligible the speaker's knowledge of her belief. In terms of the characterizations given earlier, the project is to show that epistemic privilege can be understood as a way of explaining or grounding first-person authority after all, but without doing so in terms of epistemic “access”. In his paper, Roessler paves the way for a “modest epistemic explanation” of first-person authority, according to which a speaker knows what she believes in the act of expression, rather than prior to, or independently of the speech acts she is performing (see also Roessler Citation2013). Roessler's view differs from neo-expressivism in so far as expressions are not meant to provide an alternative to, but rather are meant as a way of developing an “epistemic” explanation of first-person authority. Roessler applies this model to the phenomenon of “shared” or “joint” self-knowledge, and makes a convincing case for the idea that it is possible to claim (1) that the knowledge an audience acquires of a speaker's belief depends on the speaker's self-knowledge, without (2) committing to the traditional model according to which the audience “inherits” such knowledge by being “told” about something to which only the speaker has access. Roessler suggests that the audience's and the speaker's knowledge may share a common explanation, which lies in the speaker's sincere expression. Roessler points out that both ways of knowing may be seen as “complementary roles, or as interdependent aspects of a single shared capacity for communication”. Moreover, self-knowledge and knowledge of other minds should not, on this view, be seen as separate problems (as they tend to be seen by orthodox epistemic explanations). The view suggests that the capacity for self-knowledge is inseparable from the capacity to share such knowledge with others.

2.3.2. (In)compatibility of approaches towards self-knowledge

The second question mentioned earlier, concerning the (in)compatibility of approaches to authority and epistemic privilege, takes central stage in Kateryna Samoilova's paper. Samoilova argues for a compatibility between two views which have hitherto been taken to be strongly at odds with each other: neo-expressivism and what she refers to as the third-person view (TPV; associated with, e.g. Peter Carruthers’ work). She argues that the two views can, on closer inspection, be “combined into a single view about the nature of introspection and self-knowledge”. Whereas neo-expressivism sees self-knowledge as “special” given that we are in a unique position to speak on our own behalf, defenders of the TPV deny that self-knowledge is special because there is no special process by which knowledge of our own mental states is obtained. According to Samoilova, this incompatibility is only superficial, given that these two approaches locate the distinctiveness of self-knowledge at different levels: either in the nature or status of self-knowledge (neo-expressivism) or the process by which it is acquired (TPV). One might thus deny that introspection is special, epistemically speaking, whilst insisting that self-knowledge is distinctive in some other way, as neo-expressivists do. Samoilova points out that the main point of the paper is dialectical: to show that the assumption that different views of self-knowledge disagree on the same phenomenon may be misguided, and stands in the way of recognizing the virtues of each of those views.

Franz Knappik's paper critically engages with so-called rationalist accounts of self-knowledge. On rationalist accounts, self-knowledge regarding our propositional mental states “must be seen as part of the relation in which we stand to our mental lives qua reason-oriented, self-critical thinkers, or ‘rational agents'” (Knappik this issue). Because of its strong emphasis on this agential aspect, rationalism is often considered to be incompatible with TPV, or, as Knappik terms it, “interpretationist” accounts of self-knowledge. He provides a new argument to the effect that rationalists ought to accept a form of interpretationism in a substantial range of cases. He directs our attention to instances of self-knowledge that issue from “expressive episodes”: episodes in which one forms a second-order belief about a rational attitude one has (e.g. a belief or an intention) by consciously and spontaneously expressing that attitude in response to a question that has arisen about it. What follows is a detailed argument that aims to show that the response event in expressive episodes must involve an element of interpretation. At the same time, however, Knappik maintains that one can accept this argument whilst still holding on to the basic tenets of rationalism. The last part of the paper provides several considerations in favour of the compatibility claim that incorporation of some form of interpretationism need not be considered an obstacle for rationalist accounts of self-knowledge.

Tillman Vierkant's paper can also be regarded as centring on the issue of (in)compatibility between authority and epistemic approaches to self-knowledge. Vierkant asks the question of asymmetry specifically with regard to intentions. He focuses on an influential heuristic that philosophers have used to articulate what it means to have an intention: the idea “that in order to acquire an intention to x one must settle the question whether x” (Vierkant this issue). Interestingly, different philosophers who have used this heuristic have reached opposite conclusions. As Vierkant explains, Moran puts forward the idea of settling a question to back up an asymmetry thesis regarding self-knowledge of intentions, whereas Carruthers uses it to argue that knowledge of our own intentions is essentially observational, and hence in important respects similar to the way we know the intentions of others. How can this be? After carefully going through the dialectics of the debate, Vierkant concludes that there are two ways of understanding the phrase “to settle a question” that are at work here: one psychological, according to which to have settled a question is to have ensured the execution of an intention, and one definitional, which simply states the conceptual connection between positively settling the question whether to x and having an intention to x. The paper continues by arguing that both notions contribute to our concept of intention and explores different ways of how these contributions might work in settling the issue between Moran-like and Carruthers-like accounts.

2.3.3. The scope of self-knowledge

Cristina Borgoni addresses the question of how we come to know our “resistant beliefs”. Resistant beliefs occur when an individual continues to believe that p despite having reasons against the belief, and for which the individual lacks rational control. It is usually claimed that we cannot come to know a resistant belief in a first-personal way, but Borgoni argues that we can. First, she argues that the claim relies on two mistaken suppositions: first of all, that such beliefs are necessarily third personal, because the self-ascription is grounded in evidence, and second, that we cannot have first-personal knowledge of beliefs we do not control. Borgoni rejects both claims, and points out that ascribing a belief does not only serve the purpose of expressing our conscious commitments, but may also serve to express other aspects of our psychology, such as one's personal conflict. Second, she argues that having a lack of control over one's own belief does not necessarily imply alienation, or vice versa. She ends the article by suggesting that this approach to resistant beliefs supports a pluralist view of self-knowledge, according to which there is a variety of first-personal ways of acquiring self-knowledge.

Peter Langland-Hassan considers the question of how we know that we are imagining something, rather than merely supposing, wishing or judging something. In this respect, the paper addresses the aforementioned second question, concerning the scope of (theories of) self-knowledge, and, more in particular, the question of how different mental states or attitudes may require different explanations. Langland-Hassan argues that the question of how to explain knowledge of the fact that we are imagining poses some serious challenges for theories of self-knowledge. More specifically, Langland-Hassan considers how Bar-On's neo-expressivist view, Alex Byrne's outward-looking account and inner sense views address the question. Langland-Hassan then builds on Byrne's account to offer a proposal for how we know we are imagining in cases where our imaginings represent situations beyond what we believe to be the case. He argues that this approach preserves some of the spirit of neo-expressivism. In developing this positive proposal, Langland-Hassan distinguishes between belief-matching imaginings and beyond-belief imaginings. The former are imaginings that perfectly align with what the imaginer already believes to be the case, whereas the latter represents situations or objects beyond those the imaginer believes to be actual. Whilst Langland-Hassan sees a path towards explaining our knowledge of beyond-belief imaginings, he argues that serious difficulties remain in attempting to explain our knowledge of belief-matching imaginings.

Naomi Kloosterboer is concerned with the question of how we gain knowledge of our emotions. Her paper addresses Moran's account and his transparency claim in particular. According to Moran, we may answer the question – and gain knowledge of – what our beliefs are by answering another question, namely what our beliefs ought to be, that is, by answering the latter question by referencing the reasons for believing p. Kloosterboer argues that though this account may work for belief, it cannot be applied to emotions. She argues this is so because emotions are conceptually related to concerns – they involve a response to something one cares about. As Kloosterboer argues, this means that deliberation about what to feel cannot be limited to reflection on facts relevant to the specific evaluative content of the emotion, but should include considerations about what is important to the person in question. This, in turn, helps us to see how emotions can be understood as (ir)rational or (in)appropriate.

2.3.4. Methodology: self-knowledge and folk psychology

Victoria McGeer addresses the question of what we might learn about self-knowledge and first-person authority by exploring our “folk-psychological” capacities and practices of engaging with and gaining knowledge of others, thereby combining questions (4) and (1). McGeer revisits some of her earlier work on the “regulative view” of folk psychology (Pettit and McGeer Citation2002; McGeer Citation2007), according to which folk psychology is understood first and foremost as a socially scaffolded “mind-making” practice through which we come to form and regulate our mental states and dispositions (see also Zawidzki Citation2008). According to McGeer, the regulative view allows for a “more liberal and expansive” account of first-person authority, because it focuses not only on the “local” capacity to know (and fail to know) one's own mental states, but also on a more extended capacity to adjust and regulate one's words and deeds to repair any putative failures of self-knowledge. Given that folk psychology, on the regulative model, is always a “work in progress”, the same applies, McGeer argues, to knowing our own minds. She notes that, in contrast to some traditional epistemic views, “to fail to be ‘self-knowing’ in the psychological states you attribute to yourself is not ipso facto to fail in first-person authority”. This is because first-person authority is not a moment-by-moment capacity; it is rather sourced in “a continuing disposition to understand and live up to shared folk-psychological norms, even when you have failed in the past”. In the final part of the paper, McGeer employs the regulative model to answer the question of, firstly, why human beings are so prone to respond to one another's thought and action with praise and blame, punishment and reward; and, secondly, why we find it “normatively fitting or fair” to target one another with such reactive attitudes and practices.

In the last paper of this issue, Kristin Andrews first of all considers whether perhaps the ancient Greeks, with their advice to “know thyself”, may have had “something else in mind in addition to attending to our occurrent thoughts and sensations”, as is customary in the contemporary debate on self-knowledge. Andrews takes up the challenge of exploring a more liberal approach to self-knowledge and carefully considers the many advantages that such an approach has to offer. The starting position of the paper is that adopting the methods of Pluralistic Folk Psychology (Andrews Citation2012) will lead us to towards a better understanding of the different types of self-knowledge that we have. A first step of the Pluralistic model is to ask what, exactly, the function is of our knowledge of other minds, such as prediction, explanation and/or coordination. Similarly, Andrews considers some of the functions of self-knowledge, which includes acting (more) consistently, and making yourself more transparent and predictable to others, thereby facilitating coordination and making group knowledge possible. The central claim of the Pluralistic model is the idea that a number of different cognitive mechanisms support the ability to understand other people, including mindreading and reason explanation, but importantly also involve understanding others by reference to, for example, stereotypes, specific situations, their emotions and sensations, goals, personality traits and so on. When we expand the contents of self-knowledge to include not just thoughts and sensations, Andrews notes that we may recognize that self-knowledge is similarly diverse. Andrews stresses, moreover, that knowing ourselves is not something we do by ourselves but rather calls for a “co-creative” approach, which on its turn makes room for a new take on the advice to know thyself, which, thus understood, is really “a dictate towards empathy”.

Acknowledgements

We would first of all like to thank the authors in this issue for their fantastic papers and their valuable input during the conference. Thanks also go to the faculty of philosophy and the International Office at the Radboud University Nijmegen, as well as the research programme Science Beyond Scientism (AKC/VU Amsterdam) for making this event possible. We would like to thank Dorit Bar-On, Jan Bransen and Sem de Maagt for helpful comments on an earlier version of this introduction. Lastly, we are much indebted to the anonymous referees who have spent their valuable time reviewing manuscripts for this issue, for which we are incredibly grateful.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Fleur Jongepier is a PhD student at the Radboud University Nijmegen, and is writing her dissertation on self-knowledge and first-person authority.

Derek Strijbos is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Radboud University Nijmegen and a psychiatry resident at Dimence, Zwolle. He wrote his dissertation on the non-representational dimensions of folk psychology. His current research focuses on different themes on the intersection of philosophy and psychiatry.

Notes

1. The label “non-epistemic” is slightly paradoxical in so far as any account of self-knowledge is bound to be “epistemic”, in some sense. The point, though, is that the epistemic dimension is not the whole story about the broader topic of the relation we have to our own mental states. Hence, a more accurate label would be “extra-epistemic” rather than “non-epistemic”, which does not suggest being at odds with doing epistemology, but rather one that implies having the ambitions of going beyond it.

2. To be sure, Moran's work is notoriously hard to locate in this map, given that he approaches self-knowledge as having both epistemic and non-epistemic dimensions. Consider one of the first sentences of his book, where he describes the project as one that aims to “reorient some of our thinking about self-knowledge and place the more familiar epistemological questions in the context of wider self-other asymmetries which, when they receive attention at all, are normally discussed outside the context of the issues concerning self-knowledge” (2001, 1).

3. Bar-On discusses different epistemic accounts that can be made compatible with her own neo-expressivist view, one of which shares some of the features of the non-reductionist dependence model just discussed (see esp. 2001, 389ff.).

4. Note that the immediacy thesis is not incompatible with the psychological approach per se; after all a mechanism for introspection may deliver precisely immediate knowledge of one's own states.

5. One might argue, though, that the personal/sub-personal distinction does not map neatly onto the conscious/unconscious distinction. One might, for example, want to concede that unconscious inferences are possible whilst resisting that there could be sub-personal inferences.

6. Bar-On calls attention to a similar distinction in the context of a discussion of immunity to error through misidentification, which provides the model for the neo-expressivist account of avowals. She stresses that such immunity

concerns the epistemology of ascriptions, not their etiology or psychology. What matters is not what goes through the self-ascriber's head as (or right before) she makes her self-ascription. Rather, what matters is the epistemic grounding of the ascription (or lack thereof). (Bar-On Citation2004, 233, emphases in original)

References

- Andrews, Kristin. 2012. Do Apes Read Minds: Toward a New Folk Psychology. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Armstrong, D. M. 1968. “Introspection.” In A Materialist Theory of the Mind, edited by Quassim Cassam, 109–117. Oxford: Routledge.

- Bar-On, Dorit. 2004. Speaking My Mind: Expression and Self-Knowledge. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bar-On, Dorit. 2015. “Transparency, Expression, and Self-Knowledge.” Philosophical Explorations 18(2): 134–152

- Byrne, Alex. 2005. “Introspection.” Philosophical Topics 33 (1): 79–104. doi: 10.5840/philtopics20053312

- Carruthers, Peter. 2009. “How We Know our Own Minds: The Relationship Between Mindreading and Metacognition.” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 32: 1–18. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X09000016

- Carruthers, Peter. 2011. The Opacity of Mind: An Integrative Theory of Self-Knowledge. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cassam, Quassim. 2009. “The Basis of Self-Knowledge.” Erkenntnis 71 (1): 3–18. doi:10.1007/s10670-009-9164-z.

- Cassam, Quassim. 2011. “Knowing What You Believe.” Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 111: 1–23.

- Cassam, Quassim. 2014. Self-Knowledge for Humans. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- McDowell, John. 1998. “Response to Crispin Wright.” In Knowing Our Own Minds, edited by C. Wright, B. Smith, and C. MacDonald, 13–45. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- McDowell, John. 2010. “Brandom on Observation.” In Reading Brandom: On Making It Explicit, edited by Bernhard Weiss and Jeremy Wanderer, 129–144. Abingdon: Routledge.

- McGeer, Victoria. 1996. “Is “Self-Knowledge” an Empirical Problem? Renegotiating the Space of Philosophical Explanation.” Journal of Philosophy XCIII (10): 483–515. doi: 10.2307/2940837

- McGeer, Victoria. 2007. “The regulative dimension of folk psychology”. In Folk-Psychology Re-Assessed, edited by D. Hutto and M. Ratcliffe, 138–156. Dordrecht: Springer.

- McGeer, Victoria. 2015. “Mind-Making Practices: The Social Infrastructure of Self-knowing Agency and Responsibility.” Philosophical Explorations 18(2): 259–281.

- Moran, Richard. 2001. Authority and Estrangement. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Nichols, Shaun, and Stephen Stich. 2003. Mindreading: An Integrated Account of Pretence, Self-Awareness, and Understanding Other Minds. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Peacocke, Christopher. 1998. “Conscious Attitudes, Attention, and Self-Knowledge.” In Knowing Our Own Minds, edited by Crispin Wright, Barry C. Smith, and Cynthia Macdonald, 63–98. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Pettit, Philip and McGeer, Victoria. 2002. “The Self-Regulating Mind.” Language and Communication 22 (3): 281–299. doi: 10.1016/S0271-5309(02)00008-3

- Pryor, Jim. 2005. “There Is Immediate Justification.” In Contemporary Debates in Epistemology, edited by Matthias Steup and Ernest Sosa, 181–202. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Roessler, Johannes. 2013. “The Silence of Self-Knowledge.” Philosophical Explorations 16 (1): 1–17. doi: 10.1080/13869795.2013.744084

- Ryle, Gilbert. 1949. The Concept of Mind. London: Hutchinson's University Library.

- Spaulding, Shannon. 2010. “Embodied Cognition and Mindreading.” Mind & Language 25 (1): 119–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0017.2009.01383.x

- Zawidzki, Tadeusz. 2008. “The Function of Folk Psychology: Mind Reading or Mind Shaping?” Philosophical Explorations 11 (3): 193–210. doi: 10.1080/13869790802239235