Abstract

Why do public policies succeed or fail? The aim of this article is to contribute to answering this enduring research question in policy research through a comparative study of the variable efforts by Nordic governments to relocate their central agencies from the capital regions over a period of several decades. This was a radical redistributive policy program premised on a policy instrument – coercion – which was very alien to political systems characterized as consensual democracies. Hence, it is no surprise that only two out of seven relocation programs of any substance were successful. The really intriguing research question here is how any relocation program was achievable at all in a policy context where this was very unlikely. A broadly based multi-theoretical analytical framework linking interest groups, institutions, human agency in the form of policy entrepreneurship/design and situational factors is employed to solve this research puzzle. Findings from this study offer important contributions to the following research fields: comparative public policy, radical policy change and most specifically the so-called third generation of public policy implementation research.

Theme, Research Question, Background and Motivation

How can we explain strikingly different results when three very similar countries are pursuing an identical policy – moving central agencies from their respective capital regions – even when two of them, Finland and Norway, are doing their best to draw lessons from the undisputed leader – Sweden – in terms of successful policy performance? The observed cross-national pattern in policy performance is also counterintuitive based on information about prior national legacies in this policy domain. This is the main research question this study attempts to answer.

Relocation programs in all three countries during the 1960s and 1970s were intended to alleviate a similar Nordic problem context: increasing regional imbalances due to heavy out-migration of people from peripheral rural areas and subsequent large in-migration to urban centers, affecting especially the capital regions (Stenstadsvold Citation1975; Nordrefo Citation1988, pp. 2–3; Isaksson Citation1989, pp. 14–23).

The study is motivated by a general interest in a more fundamental and enduring research question in political science with respect to policy change: what are the conditions under which public policies succeed or fail (Ingram and Mann Citation1980; Capano and Howlett Citation2009). Approaching an answer here requires investigation of cases with both types of policy results. Thus, this study includes both successful and failed attempts at adopting and implementing agency relocation programs. We find explaining policy change against unfavorable odds more intriguing than accounting for policy continuity as expected, even though these two foci are, of course, polar opposite aspects of the same issue. Policy change as the dependent variable in this respect is quite unambiguous in its simplicity and clarity: it is simply whether a relocation program is implemented or not after it has been endorsed by legislators. Our definition of the slippery and normatively laden terms, policy success or failure, are pragmatically defined likewise: i.e. relative to the political will and program goals expressed through majority votes in national legislatures.

Agency relocation programs of the type in focus here, being of a radical redistributive nature, are among the most difficult policies to adopt and implement (Lowi Citation1964; Ripley and Franklin Citation1982). They were radical in the sense that they were premised on a type of policy instrument – coercion – that is very unusual and alien to Nordic political systems characterized as consensual democracies because of their policy style emphasizing cooperation and consensus among stakeholders as means to produce legitimate compromise solutions (Elder et al. Citation1983; Lijphart Citation1984; Arter Citation[1999] 2008). Hence, agency relocation programs should be ideally suited for our analytical purpose: explaining policy change against very unfavorable odds as a strategy to identify salient critical conditions under which policies succeed or fail more generally.

Methodology

Our comparison of agency relocation programs is based on a small-N qualitative and most-similar-systems research design both between countries synchronically and within each country diachronically and longitudinally (George and Bennett Citation2005). The advantage of this research design has been summarized by Lipset (Citation1990, p. vi): “the more similar the units compared the more possible it should be to isolate the factors responsible for differences between them”. Few countries in the world are more similar in so many respects as the Nordic countries (Lijphart Citation1984; Lane and Ersson Citation1994; Arter Citation1999). Hence, they are ideally suited for this particular research design.

At an earlier stage of this research project only Norway and Sweden were included in the cross-national comparison. Finland was included later for three reasons. First, to alleviate the over-determined research design caused by the familiar “too few cases, too many variables” syndrome (George and Bennett Citation2005) associated with small-N comparison by increasing the number of relocation programs from five to seven. Second, because this introduced more variation in one of the hypothesized key independent variables: type of political system and government. Third, because this provided a wider and hence tougher “testing ground” (see Stinchcombe Citation1968) regarding our main theoretical proposition explicated below.

This “testing” takes place in a crucial policy context – the Nordic countries – with the strongest organized interest groups worldwide (see Alvarez et al. Citation1991, p. 553), where chances of confirming an interest group politics type of explanation are maximized and conversely chances of confirming institutional explanations are minimized. This crucial case testing logic is an important integral part of our cross-national comparison intended to further enhance the explanatory power of this quite rigorous research design (Gerring Citation2007). Agency relocations are not representative policy cases. On the contrary they are deviant, extreme and revelatory cases (i.e. with respect to type of policy issue and inherent policy instrument, conflict intensity and bureaucratic politics at play), all of which make them optimally suitable for our analytical purpose – crucial case testing procedure – whose ambition is theoretical rather than empirical generalization (Yin Citation2009).

This study spans national policy processes going through two policy cycles in Finland and Sweden and three in Norway. Governmental efforts at the first policy cycle (1960s) with respect to agency relocation programs during the 1960s were clearly of a preliminary, tentative and less committed nature in all three countries. For this reason, as well as not to overwhelm the reader with too many detailed case histories, more attention is devoted to what happened in subsequent policy cycles – the 1970s (and the 2000s in Norway) – when governmental actions were of a more committed and serious nature.

With respect to data, the study relies heavily on the following sources of information: two doctoral dissertations from Finland and Norway (Sætren Citation1983; Isaksson Citation1989); a book and a journal article describing the third Norwegian policy cycle in quite unusual detail at the highest level of political decision making (Norman Citation2004; Meyer and Stensaker Citation2009) – two of these authors were key decision makers themselves; some quite thoroughly documented public evaluation reports from Sweden (Edstad Citation1980; Pettersson Citation1980). Finally, this author conducted some supplementary interviews in Stockholm in autumn 1983 with the top civil servant (Nils Finn) responsible for implementation of the Swedish relocation program after 1978.

Theoretical Framework and Derived Main Proposition

All central agency relocation program cases analyzed and compared in this study, not surprisingly, point clearly in the direction of a common critical bottleneck in the policy process – the cabinet as a formal political clearinghouse. This raises a more focused research question: why is there variation in cabinet performance on an identical policy program not just between but also within countries? Factors that make governments and their cabinets strong or weak in terms of policy making have been investigated by several policy scholars (Steinmo et al. Citation1992; Weaver and Rockman Citation1993; Olsen and Peters Citation1996; Pollitt and Bouckaert Citation2011; Doorenspleet and Pellikaan Citation2013). Thus, the historical-institutional (HI) approach expounded by these scholars (see e.g. March and Olsen Citation1984; Steinmo et al. Citation1992) presents itself as a logical primary theoretical starting point given our more precise research question. This choice may seem odd to some as the HI approach is generally credited with explaining policy continuity better than policy change. However, this interpretation is heavily premised on only one of the two faces of institutions – namely their constraining impact on the policy process. The other face, highlighting institutions’ enabling and facilitating impact on policy making, is then ignored. In this study we recognize both faces of institutions, thus adopting a dynamic rather than static interpretation of the HI approach (Olsen Citation1992; Peters et al. Citation2005).

Nevertheless, even this more nuanced dynamic interpretation of institutional impacts has its clear limitations. Institutions may facilitate the policy-making process, but they do not make decisions. People in them do! This strongly suggests that human agency must be an integral part of the institutional approach. Institutions combined with benign environmental circumstances may create opportunities for political action, but those opportunities must be recognized and capitalized on by some authorized decision makers using their personal will and skills as well as institutional capabilities and resources before windows of opportunity close. Kingdon (Citation1984) referred to decision makers of this kind as policy entrepreneurs.

Wilson (Citation1973), elaborating on Lowi’s (Citation1964) famous policy typology, had by then already hypothesized policy entrepreneurs to play a particularly critical role in redistributive policies of the kind we are studying. That is, programs where costs are narrowly concentrated on resourceful groups in the capital regions and benefits intended to be widely distributed to less resourceful areas outside the capital regions (see ). Wilson’s proposition is based on the assumption that redistributive policies of this type tend to target better-off segments of society, which must bear most of their costs. Hence, these citizens will tend to not only resent but also oppose such policies, and have many resources to succeed in this respect while those less well-off usually have fewer resources to defend policies that are supposed to benefit them. This imbalance in strategic resources between these two differently impacted target groups will tend to result in either no policy program at all or alternatively greatly reduced policy program benefits (and hence also costs) in terms of size and scope – i.e. interest group politics in Wilson’s typological scheme. The more optimal agency relocation program from policy makers’ point of view (narrowly concentrated costs and widely distributed benefits) supposedly requires the presence and actions of policy entrepreneurship. That is why Wilson attached the label entrepreneurial politics to the ideal-typical large-scale relocation program that this entails. Thus, Wilson’s insight points towards the important role of deliberate design efforts in policy entrepreneurship with respect to organizing the policy process as a means to achieve the desired optimal policy program (Howlett Citation2011).

Table 1. Policy types by Wilson (Citation1973) and their assumed related type of politics.

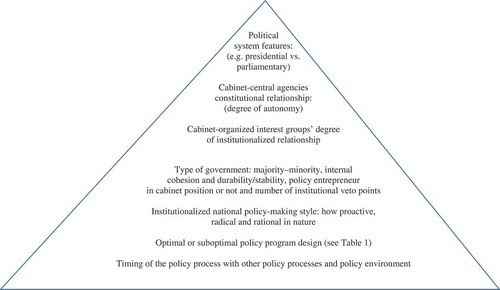

and illustrate our multi-theoretical framework, whose basic elements stem from previous policy research (in particular Wilson Citation1973; Kingdon Citation1984; Olsen Citation1992; Weaver and Rockman Citation1993; Olsen and Peters Citation1996; Pollitt and Bouckaert Citation2011) as well as our own comparative study. Further elaboration and explanation of various constitutional-institutional arrangements and their policy-facilitating and -inhibiting capabilities will, due to limited space, be dealt with below in the comparative section, where we try to explain differences in policy performance between as well as within countries. briefly summarizes those efforts.

Table 2. Summary of factors found to explain policy success and failure and their configuration across the three Nordic countries with respect to agency relocation programs during the 1970s (and 2000s in Norway).

Figure 1. Multi-theoretical framework operationalized into different types of factors assumed to impact on policy-making performance

The sum of the above theoretical reasoning leads to three main propositions that will guide this comparative study:

Proposition 1: Agency relocation programs in cell 1 of will be adopted by legislatures and subsequently implemented, while programs in cell 2 will be more frequently contested, opposed and rejected.

Proposition 2: Designing politically optimal relocation programs (cell 1) in the policy formulation stage requires political will, commitment and perseverance embodied in and executed by a institutionally well-positioned policy entrepreneur. Absence of a policy entrepreneur will lead to proposals of politically suboptimal relocation programs.

Proposition 3: Policy entrepreneurs operating within strong governments combined with other policies facilitating institutional arrangements and a beneficial situational context will be most effective in proposing politically optimal relocation programs, while weak governments with no policy entrepreneur and a less benign situational context will fail to achieve the same.

The Swedish Case History: 1957–1980/81

In May 1973 the Swedish parliament enacted the second and final part of a relocation program of unprecedented scope, totaling some 50 central governmental agencies located in Stockholm with more than 10,000 employees. The relocation program had a very well-balanced regional scope benefiting 16 cities located in all major regions outside the capital and a couple of other metropolitan areas. Hence, three out of four legislators voted in favor of this relocation program. This parliamentary decision was preceded by another in 1971 involving 30 central agencies with 6,300 employees.

A commission appointed by the government in 1969 to investigate which agencies were most suitable for relocation had proposed in two separate reports (SOU Citation1970, p. 29; SOU Citation1972, p. 55) a relocation program almost identical in content and scope. Commission membership was most noticeable for its lack of representation from political parties and interest organizations. They were for the most part, including the chairperson, civil servants close to and handpicked by the influential and powerful finance minister, Gunnar Straeng, with a clear mandate to propose substantial agency relocations as soon as possible. During its work the commission had fairly little contact with agencies under investigation and unions organizing their employees. Consultations only took place at the highest level involving a number of junior ministers.

The commission’s reports were distributed widely for comments, as is customary in Sweden, to institutions, agencies and organizations of various sorts. The response to its proposals was overwhelmingly negative. The Federation of Trade Unions, with close ties to the ruling Social Democratic party, surprisingly endorsed the proposed relocation program. The other major unions organizing white-collar workers in the public and private sector did not support the relocation program, but they did not engage much in mobilizing their membership to oppose it. The government acted quickly, drafting its parliamentary bills in 1971 and 1973 without any further consultation, paying little heed to the flood of prior negative comments. Both the cabinet and the legislators not only endorsed but actually increased to some extent the number of agencies and new location sites proposed by the commission.

The challenge of implementing this large-scale and logistically demanding relocation program was solved through the typical Swedish style of meticulous organization and planning. The linchpin in this respect was an inter-ministerial coordinating group under the auspice of the Prime Minister’s Office with secretarial assistance from a project/work group established within the Finance Ministry for this specific purpose. Thus, only few agencies exceeded the stipulated time frame for moving from the capital.

True to its thorough manner of doing things the Swedish government sponsored an impressive number of studies that were aimed at evaluating the various impacts of the relocation program (e.g. Edsta Citation1980; Petterson Citation1980). The results are too voluminous to be detailed here. As a general conclusion it is safe to say that many of its predicted positive effects were noted while most of the anticipated negative effects never materialized or turned out to be quite overstated. One example was the costs associated with this large-scale relocation program. They turned out to be 15 per cent lower than expected, resulting in estimated budgetary net savings in 1986/87 of 270 million kroner, mostly due to lower office accommodation costs. Only 20 per cent of employees relocated with their agencies. The effect of this was the creation of many thousands of new jobs in the new locations of the agencies. However, Stockholm also experienced a growth in total jobs during the 1970s, approximately equaling the number created elsewhere. Nevertheless, the proportion of central government employees in the capital decreased from 30.5 per cent in 1972 to 26.7 per cent in 1987 (NordRefo Citation1988).

This was not the first time the Social Democratic government considered the possibility of a fairly large-scale relocation of its central agencies in Stockholm. In 1957 it also appointed a commission (called Lokaliseringsutredningen in Swedish) to investigate its feasibility. The commission was well staffed in terms of secretarial resources and enlisted the assistance of external professional experts to investigate various aspects of a comprehensive relocation program. No concrete relocation program was proposed indicating which agencies should be moved to a specific location. Instead the commission outlined a very large-scale relocation program and an alternative more modest one.

The commission report was also then distributed widely for comments. A large majority of the responses were quite negative, especially from those agencies most directly affected by the suggested relocation plans. Perhaps in view of these mostly negative responses the government decided to abandon further work on this policy issue. Instead it opted to pursue another type of regional policy measure that had been investigated and proposed parallel to Lokaliseringsutredningen, called Active Location Policy. The latter program targeted private sector enterprises, offering them various types of incentives to relocate their businesses from overcrowded urban to more rural areas.

The Norwegian Case History: 1961–2007

In the early 1970s it would seem that Norway, not Sweden, was the undisputed leader in efforts at moving central governmental agencies from its capital, as it was the only Nordic country that had some success in doing so during the previous decade. But on closer scrutiny this proves to be much less the case. The relocation program proposed by a government-appointed commission in 1961 was not very ambitious. Nevertheless, by the time affected stakeholders, the cabinet and legislators had had their say on it, its size and scope, it had been depleted of even more substance, to such a degree – i.e. eight agencies totaling 400 jobs to five cities close to the capital – that it was rendered a mostly symbolic program.

Efforts by the same government to follow up on this limited relocation program with proposals for more substantial future relocations, which it had pledged to do during the parliamentary floor debate on its white paper in 1967, proved very hard to deliver. This was partly the result of widespread resistance in the governmental bureaucracy but also in no small part due to ambivalence and failure on the part of the government itself to support those entrusted with the task of delivering on its promises. Thus, by the early 1970s the relatively long lasting but internally weak center-right majority coalition government, led by a prime minister from the Center (former Agrarian) party, had achieved little if anything in terms of giving more substance to its previous mostly symbolic relocation program.

In view of these prior events it is somewhat surprising that the new but short-lived minority coalition government formed of center parties decided in 1973, a couple of weeks before the general election, to appoint a new commission to investigate the feasibility of a larger scale relocation program. The motivation seems to have been twofold: (1) pressure from the city government of Oslo to reinvigorate work on moving government agencies from the capital due to heavy net in-migration during the late 1960s and (2) probably both some embarrassment and also inspiration from what the Swedish government had accomplished in this policy area the same year with the enactment of its impressive and bold relocation program.

The new minority Labor government that won the general election in 1973 apparently shared the political commitment of its predecessor on this policy issue. In fact most political parties had pledged before that election to support the new initiative. The strategy now was obviously to try to emulate the successful policy process in Sweden. Thus, a new commission was asked to come up with some concrete relocation proposals relatively quickly in a first report that the cabinet could then submit to the parliament for its approval. This procedure was thought to give authority and legitimacy to both the commission and the government in their subsequent efforts to realize a Swedish-style agency relocation program.

The commission – hereafter named the Grande commission after its chairperson – did what it was asked to do. In its first report delivered in 1975 12 central agencies and parts of three others with approximately 1,000 employees were listed as suitable to be moved from Oslo, though without indicating where. The ministry appointing the commission had itself to decide on this politically sensitive issue. As before, the ministry distributed the report widely and received the same type of mostly negative responses. The ministry also wasted little time in drafting a white paper on the relocation issue based on the recommendations from the Grande commission. That is when things started to go awry. In a newspaper interview in late autumn 1975 a junior minister and associate member of the Grande commission revealed that concrete relocation proposals to be included in the parliamentary white paper had been met with considerable objections from ministers responsible for the central agencies in question. Hence, meetings between his lead ministry and these members of the cabinet were scheduled to secure their and the cabinet’s approval of the proposed relocation program. It would take 2–3 years before the cabinet was able to submit a white paper on this issue to the parliament proposing moving 20 agencies with some 1,200 employees to some still undisclosed new locations outside Oslo. The parliament endorsed plans for such a relocation program but once again the government encountered heavy resistance within its own ranks as soon as it started work on implementation. A one-day strike among employees in affected central agencies organized by their unions in late autumn 1980 seems to have been the precipitating event causing the final collapse of the government’s political will to pursue the relocation program. Announcement of this policy reversal by the lead minister in parliament in early January 1981 was met by legislators with a deafening silence. Hence, not only were the few relocation proposals in the parliamentary white paper abandoned, but more importantly so were subsequent substantial relocation proposals contained in the two most recent reports from the Grande commission submitted in 1977 and 1979, affecting in whole or in part more than 50 central agencies with close to 5,000 employees.

Contrary to what one might expect by now, this is not the end of the story on the relocation program in Norway. In June 2003, exactly 30 years after the Swedish parliament completed enacting its impressive relocation program, a clear majority in the Norwegian parliament endorsed moving seven central agencies with some 1,000 employees from Oslo to seven cities with a fairly balanced regional distribution. Even more noteworthy, in view of the prior policy history, is the fact that all agencies – despite substantial logistic challenges and heavy opposition in at least one case – were now moved to their new locations within the stipulated time frame of four years. While the scope of this relocation program pales in comparison with the Swedish one, the way in which it was achieved is much more remarkable.

It started with general election in autumn 2001 that resulted in a center-right minority coalition government (Bondevik II). The choice of Victor Norman (VN), an economics professor with no previous political experience, as minister of Labor and Government Administration (LGA) was a surprise to most observers and commentators. Being appointed with a specific mandate to modernize the public sector, he launched a new modernization program on behalf of his government in early 2002. Reorganizing and streamlining regulatory agencies in accordance with contemporary New Public Management (NPM) doctrines was a centerpiece of this modernization program. Relocating some of these agencies became part of the reform and turned out, not surprisingly, to be by far the most controversial issue in this respect. The latter idea was clearly the brain child of VN. He reasoned that since regulatory agencies were supposed to be largely politically autonomous and functionally independent there was less need for them to be located near other government institutions in Oslo. Hence, they were well suited to be part of a relocation program. Apparently VN did not consult or inform either the chairperson of his own political party (who was also a fellow cabinet minister) or his prime minister before, in January 2002, he announced the government’s plan to relocate some regulatory agencies as part of the modernization program. This seems to have been a deliberate act on his part intended to lock his government into a policy position from which it could not retreat without losing considerable political face in the eyes of the public (see Norman Citation2004, p. 99).

The way Victor Norman organized the policy formulation process regarding the regulatory reform program was equally unconventional. He decided not to follow the standard procedure of appointing a public commission to investigate the policy issue and recommend possible solutions that various stakeholders then are invited to comment on before the cabinet eventually makes up its mind about whether and if so how to pursue it further with respect to the parliament. Instead VN chose to organize all work on the regulatory reform program within his own ministry in the form of a temporary project under his supervision. His junior minister (later his wife) supplemented by a political advisor and three LGA civil servants were given responsibility for coordinating the work together with two junior ministers from other ministries. This was intentionally a political project team. The junior ministers reported to their respective ministers thereby ensuring that all parties in the coalition government were involved. This meant that a number of other stakeholders both within and outside the government – such as the regulatory agencies, their labor unions, academic experts etc. – were excluded from the policy formulation process. Other civil servants in the LGA ministry and those from other ministries were also deliberately excluded at this stage of the policy process. The latter move was particularly controversial but nevertheless continued through most of the project before the cabinet decided they had to be included in its final stages.

This very exclusive political project team supervised by VN and his junior minister worked on the various elements of the regulatory reform program from April to late autumn 2002 with two exceptions. The junior ministers representing other ministries and governing political parties were so skeptical towards one reform idea (closer monitoring of local municipalities) that VN decided to take it off the project team’s agenda. The other exception was the relocation issue, which was not on its agenda in the first place as VN did not trust even this handpicked political team to agree on concrete relocation proposals. Hence, most members of the project team did not know exactly which regulatory agencies would be part of the proposed relocation program until its final meeting when all reform elements had to be put together in its report. Just before this meeting cabinet members whose ministries were affected by the relocation program were informed about this fact. Surprisingly, in view of previous similar efforts, none of them objected this time. Shortly afterwards the full content of the planned relocation program was disclosed to the public.

The white paper submitted to the parliament in January 2003 reflected the fact that several changes and modifications had been made within the coalition government regarding clarification of roles/responsibilities and political autonomy/independence issues during the policy formulation process so far. Negotiations and further compromises on these issues with the opposition parties continued during parliamentary deliberations on the white paper. The exception here was the relocation program that was forwarded intact as initially proposed to the parliament. Though approved by a large majority of the legislators this did not happen without considerable opposition from some relocation program stakeholders. Especially the exclusion of affected agencies and their labor unions was highly controversial and caused a major uproar amongst their ranks, supported by the major national newspapers also located in Oslo. However, the mobilization against the relocation program began late due to the secrecy surrounding most of the policy formulation process. Hence, it was not very successful.

The Finnish Case History 1961–1976/77

The first investigative commission appointed in 1961 delivered its report as soon as late 1962. The commission and subsequently the cabinet in 1963 proposed a fairly modest and regionally very lopsided relocation program with only two cities outside the Helsinki region being included. Even worse was the fact that one of them was destined to receive four of the six agencies as well as 90 per cent of related jobs. Not surprisingly, the parliamentary bill proposing this relocation program ran into a lot of trouble once the legislators – who objected to its content – started dealing with it. Thus, after a complex, lengthy and very acrimonious deliberation process lasting for almost two years, the cabinet finally withdrew the bill altogether.

The second commission to investigate relocation of central agencies was appointed in 1972. Of its 12 members half were politicians and members of the parliament. They were from constituencies located in the middle and northern parts of the country some distance from the capital region in the south. Many of them apparently belonged to the Social Democratic party. It also had a secretarial staff of three persons at its disposal. The commission worked fast, thoroughly and effectively enlisting experts to carry out special investigations on its behalf. In two separate reports, submitted in 1973 and 1974 respectively, it recommended that some 30 central agencies totaling approximately 6,000 employees be moved to 12 different cities, of which four were located in the southern part, five in the middle part and three in the northern part of the country. In terms of jobs, their distribution towards regions farther away from the capital was even better, as the four agencies destined for the southern region had only 1,000 staff. The commission strongly advised that the cabinet should make a clear principled policy decision on its proposals detailing which agencies should be moved where, when and how.

The cabinet did make some sort of a policy decision in December 1974 but it was vague and non-committal in nature towards the proposed relocation program, emphasizing other alternative regional measures as preferable if they could achieve the same policy objectives. The cabinet also stressed that further work on these issues was to be based on cooperation with affected ministries and their subordinate agencies. A decentralization office, mandated to follow up this policy decision, was established within the administrative division of the Finance Ministry the next year (1975). Efforts by several subsequent, short-lived governments during the 1970s and into the 1980s to follow up on the commission’s proposals by submitting some of them to the parliament were unsuccessful, again primarily due to the lengthy, complex deliberation process in the parliament. In autumn 1981 the Social Democrats suggested to their coalition partner of many years, the Center (former Agrarian) party, that the issue of relocating agencies should be dropped altogether. The suggestion was not appreciated by the latter party. After 1985, efforts to relocate agencies seemed to evaporate without any explicit policy decision having ever been made one way or the other regarding the proposed relocation program.

Explaining Differences in National Policy Performance

The overall constitutional political system features of our three countries are, as we said in the introduction, very similar. Hence, it follows from our comparative research design that we cannot explain differences in policy outcomes between or within countries with factors that are invariant. The exception here is Finland, which has a semi-presidential system with a politically much stronger head of state. Hence, we will discuss the implications of that fact for the Finish policy context. As for Norway and Sweden, we think, much like Weaver and Rockman (Citation1993) found, that lower level political system features are much more important.

Sweden

Let us start with the puzzling success in the Swedish case. Why were the clearly best organized and most influential interest groups in the world (Alvarez et al. Citation1991, p. 553) – which had the most to lose from the proposed very large-scale relocation program – nevertheless also clearly least effective in blocking its realization? The answer to this paradox can to a large extent be found at lower institutional levels.

Type of Government and Institutional Veto Points

First of all Sweden had one of the strongest (single-party majority), most stable (see Appendix ) and longest lasting governments in Europe (in power uninterruptedly from 1945) up until the enactment of the final part of its agency relocation program in 1973. The Social Democratic party ruled for another three years in a single-party minority government with negotiated support from opposition parties in parliament on vital political issues. This strong political regime was enhanced by a unicameral parliamentarian political system with a ceremonial-symbolic head of state and politically self-constrained judiciary amounting to very few institutional veto points.

Government-organized Interest Group Relations

This unprecedentedly long-lasting and strong Social Democratic regime impacted on Swedish politics and society in many ways. Political scientist Nils Elvander, an expert on Swedish interest groups, described one such regime impact which is of crucial importance to this study. Through comprehensive elite interviews with politicians, business and union leaders conducted in the early 1970s he found surprisingly strong consensus among all elite groups on some powerful self-constraining and disciplining behavioral norms regarding participation in public policy-making processes. Thus, the use of objective factual information and convincing arguments presented directly to decision-making institutions and refraining from threats, blackmail, heavy-handed pressure or agitation and appeals to public opinion were heavily stressed. Furthermore, those who violated these “rules of the game” risked damaging their reputation and hence also reducing their influence (Elvander Citation1974, pp. 41–42). Elvander’s own interpretation was that Swedish associations of all kinds to a surprisingly large extent had adapted to these “rules of the game”. This may explain the somewhat surprising consent to agency relocations by the Federation of Trade Unions and less aggressive actions by the white-collar unions.

A Unique National Policy-making Style

Elvander’s findings are supported by other observers noting that Sweden at this time had a unique national policy style compared to many other countries in Western Europe, even the other Nordic countries. The unique feature of Swedish policy making was that it tended to be more proactive, rationalistic and radical (Anton Citation1969; Richardson Citation1982). This also explains why Sweden tended to be the innovative leader more generally in a Nordic policy context at this time (Karvonen Citation1981).

Relationship between Cabinet Ministers and Central Agencies

The very strong autonomous and independent role of central agencies in the policy-making process is another important institutional factor in our context. Paradoxically it became a liability, not an advantage, for them in this particular policy process. The reason for this is that the nearly universal ministerial rule and responsibility principle with respect to central government agencies does not apply in Sweden. The constitution actually prohibits cabinet ministers from interfering in how central agencies interpret and execute public policies in individual cases. Hence, it is the cabinet as a collective body to which central agencies are subordinate. We surmise that this Swedish institutional exceptionalism may actually have insulated individual cabinet ministers from strong lobbying and pressure group activity by central agencies, thus greatly facilitating unanimous cabinet decisions on a highly controversial and contested political issue.

Policy Entrepreneurship and Policy Design

The crucial role of policy entrepreneurs in promoting and ensuring policy change has been recognized by several policy scholars (Wilson Citation1973; Kingdon Citation1984). Our Nordic policy cases are no exception. The influential role of the long-serving and reputedly charismatic and strong-willed finance minister Gunnar Straeng during the 1960s and early 1970s is legendary. In our context it became evident how during the early 1970s he fronted the cabinet’s uncompromising stance on the large-scale relocation program against various stakeholders, not the least with respect to affected agencies and their labor unions. As we saw, Straeng used his institutional position to organize key stakeholders out of the policy process at the important commission stage.

Additional Push and Pull Policy Facilitating Factors

Other circumstances – two “push” and one “pull” – probably also contributed to the impact of the above-mentioned factors. The first push factor was a shortage of office space in the Stockholm area that had lasted most of the post-war period – a situation that did not improve due to quite strict local government regulations on constructing new office buildings. The second push factor was the dramatic increase in migration of people to the capital during the late 1960s.

The pull factor had to do with a national regional policy measure intended to stem the flow of people and jobs towards the three largest urbanized centers (Gothenburg, Malmoe and Stockholm) by establishing a system of growth centers located at different administrative levels in other regions. The largest designated regional growth centers, of which there were some 20, were called primary centers or big city alternatives (Nilsson Citation1992). The political process of finalizing this alternative growth center system was remarkably synchronized with that pertaining to agency relocations of the 1970s. This greatly facilitated the politically thorny question of deciding which cities should receive the relocated agencies. Thus, of the 16 new locations to which agencies were relocated almost all were designated primary centers.

Timing of the Policy Process

The timing of the second Swedish policy cycle relative to other policy processes and changing political circumstances during the latter part of the 1970s probably also contributed to some extent to the remarkable success of the Swedish policy. Limited space does not allow us to elaborate too much on these other factors. Finalizing the relocation program the same year that marked the beginning of the end of the long-lasting and strong Social Democratic regime in 1973 and its demise in 1976 to be replaced by several short-lived non-socialist coalition governments into the early 1980s is one important factor. Since implementation of the relocation program was well on its way by then no efforts were made by subsequent governments to abort a policy program that some of the coalition partners had changed position on and opposed in 1973.

Another factor was the public debate and legislative initiatives to strengthen workplace democracy for employees in both the private and public sector that came onto the government’s agenda around 1973 and was enacted by parliament in 1976, three years after the relocation program. There is no doubt that by 1973 the latter legislation had already started to undermine the legitimacy of agency relocations premised on a coercive policy instrument, though not yet seriously threatening its clear legislative majority.

A third factor was the dramatic worsening of Sweden’s macro-economic performance from the early to the late 1970s, which resulted in a budget deficit during the implementation of the relocation program. Finally, the period of remarkable harmonious and peaceful coexistence between the government and unions in Sweden came to an end by the late 1970s, with worsening macro-economic performance and the emergence of some new quite controversial issues dealing with nuclear energy, pension funds and taxes.

Hence, in view of these emerging policy-inhibiting factors relative to Sweden’s large-scale relocation program it is questionable whether it would have been seriously considered, proposed, adopted and implemented by the cabinet and parliament had the second policy cycle been delayed by just 4–5 years, starting in 1974/75 instead of 1969.

Norway

The dismal policy performance in Norway during the 1970s is also somewhat puzzling in view of its clearly leading regional policy legacy up until then. Being the only Nordic country that had succeeded to some extent in relocating central agencies from the capital during the 1960s adds to this paradox. Why then did the strongly worded, broadly based and apparently sincere political will to emulate Sweden’s ambitious relocation program in the early 1970s evaporate so fast during the second policy cycle? Even more puzzling in view of this troubled past is the adoption and implementation of a relocation program some 20 years later. We think there are a handful of factors that together offer the best explanation for this mixed policy performance.

Type of Government and Institutional Veto Points

Governments during most of the 1970s were actually of the relatively strong type (single Labor party minority governments), though weaker than those in Sweden. During the 2000s two even weaker types of governments were in power. The first was the Bondevik II non-socialist minority coalition government from 2001 to 2004. The other one was the Stoltenberg across the socialist and non-socialist blocs majority coalition government from 2005 to 2013. Since Norwegian agency relocation programs – in the 1960s and 2000s – took place under weaker coalition governments and failed attempts were during stronger government in the 1970s we must look for other factors than type of government to answer this mixed policy performance.

Much like in Sweden, there are also few veto points in the Norwegian political system and this did not change during the time period under study. What about the two other constitutional-institutional features so salient in the Swedish case?

The Relationship between Cabinet Ministers, Central Agencies and Organized Interest Groups

In contrast to Sweden, in Norway (and Finland) the relationship between the cabinet and central agencies is based on the ministerial rule and responsibility principle. This implies much closer contact between the central agencies and cabinet ministers and their executive ministries. Thus, Norwegian central agencies at this time reported on average more than twice the frequency of contact with their parent ministries than the Swedish central agencies did. Even more importantly perhaps, contacts with more aggressive and militant interest organizations were generally three times more frequent among Norwegian central agencies than among the Swedish (see Appendix ). The implication is that central agencies in Norway were in a more favorable strategic position to exert pressure on their superior ministries and cabinet ministers both directly and indirectly through their closer and more intimate contact patterns. Under the cross-pressure emanating from constitutional responsibility to respect and execute the will of the legislature on the one hand and obligations to protect and defend vested interests of subordinate central agencies on the other, cabinet ministers with few exceptions sided with the latter. They might at best agree to relocation programs as a general idea but nevertheless invariably object to those that included any of their subordinate agencies. Thus, opposition to any relocation program at cabinet level intensified the closer the decision process came to giving it real substance and political endorsement. The ministerial rule and responsibility principle with respect to central agencies and the presence and actions of more aggressive organized interest groups probably offer the best explanation for the government’s policy reversal on this issue in the early 1980s as well as the hollow and symbolic relocation program of the late 1960s. However, as these institutional features did not change much in the 2000s we must look to other factors to explain what happened then.

Policy Entrepreneurship and Policy Design

Lack of a policy entrepreneur at cabinet level to champion the controversial relocation program combined with a more aggressive, militant and less self-disciplined role of labor unions in the policy process and an incomplete and underspecified relocation program design in terms of receiving regions and cities no doubt also contributed in no small part to its eventual demise during the late 1970s. The important fact about the Bondevik II government of the first half of the 2000s was not, as we have said above, its type of government, but rather that it had a policy entrepreneur – Victor Norman – in a cabinet position. It is hard to exaggerate the crucial precipitating role he played in realizing the politically optimal agency relocation program that everybody considered his pet project. We have detailed above how he achieved this remarkable feat against very unfavorable odds through deliberate policy design where he – much like Gunnar Straeng in Sweden – organized adversely affected stakeholders and other opponents out of the policy formulation process. He paid a heavy personal and institutional price, spending most of his political capital on a rather ruthless policy style where he used his constitutional prerogatives to the fullest. Hence, it is perhaps no surprise that he returned to his academic post before the government’s time had expired but after the relocation program had been endorsed by the parliament.

Timing

Contrary to what we saw in Sweden, in Norway the timing of the 1970s policy process with other policy processes and external circumstance was clearly suboptimal. Though the process of institutionalizing workplace democracy for public employees started later in Norway than in Sweden it nevertheless came to parallel rather closely and adversely impact on the decision regarding the second relocation program because of the protracted policy cycle. The more Norwegian politicians got engaged in the debate on legislating for workplace democracy during the latter part of the 1970s the more ambivalent they became about supporting a program premised on the use of a coercive policy instrument. Hence, it is probably no coincidence that the cabinet’s policy reversal on agency relocations happened approximately at the time when public employees’ rights to co-determination on organizational issues pertaining to their workplaces had been substantially strengthened and legally formalized.

Agenda-setting circumstances were quite different during the early 2000s, as we described earlier. Now it was not inter-regional migration of people but modernization of regulatory agencies in an age of New Public Management reforms that brought the relocation issue back on the governmental agenda. Victor Norman saw this as window of opportunity, not only to modernize central regulatory agencies but also to relocate some of them. Other factors that were important during the 1970s seems to have been less significant due to his heavy-handed approach.

Finland

Finland, with the clearest and most consistent cases of policy failure, also constitutes a paradox in some respects. Net out-migration from rural peripheral areas and in-migration of people and hence agglomeration pressures of various sorts in the capital region were clearly at a higher level than in Norway and Sweden. All major political parties were represented in the second commission of inquiry that unanimously proposed the ambitious and large-scale relocation program. Furthermore, Finland had both the consistently broadest based governments and by far the politically strongest head of state in the president. He was from the Agrarian, later Center party, which most consistently and strongly advocated relocation of central agencies as a regional policy measure. Finland was also alone in creating a separate unit in the lead Ministry of Finance in 1975 to promote further work on decentralization measures. How could the proposed relatively large-scale and regionally well-balanced relocation program be defeated with these many apparently beneficial factors in favor of it?

Type of Government and Institutional Veto Points

The first and perhaps most important and surprising clue to an answer is the fact that Finland, contrary to what one might easily assume, had quite weak and short-lived governments during the 1970s and well into the 1980s (see Appendix ). It has been observed repeatedly that oversized multi-party majority coalition governments spanning the divide between the socialist and non-socialist blocs can actually be weak, especially when dealing with radical and controversial policies. This is so because there is a good chance that interests which are adversely affected by and opposed to those policies are represented in the government (Weaver and Rockman Citation1993; Pollitt and Bouckaert Citation2011). This was very much the case in Finland where virtually all governments during the 1970s were dominated by the two largest coalition partners – the Center party and the Social Democrats – which had polar opposite views on the proposed relocation program. Hence, not only was the internal cohesion of Finnish governments low, so was their stability. Finland had no less than 11 very short-lived oversized majority multi-party coalition cabinets just during the second policy cycle of the 1970s. The Center party and the Social Democrats could only agree to disagree, resulting in cabinet stalemate on this thorny policy issue lasting for many years into the mid-1980s.

The main reason for these broadly based majority coalition governments was the “qualified majority rule” of the Finnish parliament which enabled one-third of the legislators to block the enactment of any government bill by suspending further deliberations and delay a vote on it until after the next general election. Another policy-constraining feature of the same body was the many standing committees and readings involved in deliberation on and final enactment of government bills (Arter Citation1999). Bills on proposed relocation programs were subject to these very complex and cumbersome parliamentary procedures both in the 1960s and late 1970s/early 1980s.

Why was it easier to reach political agreement on agency relocations in the commission than in the cabinet or parliament? We surmise that this is because it is easier to reach agreements on a recommendation in a commission where people work closely together for an extended period of time in isolation from the public and various adversely affected stakeholders. Other reasons are discussed in relation to the next factors in our analytical theoretical framework.

The Relationship between Cabinet Ministers and Central Agencies

We think the principle of ministerial rule and responsibility with respect to central public administration worked much the same way in Finland as in Norway by exposing cabinet ministers to strong pressure to oppose agency relocations from civil servants in affected ministries and their subordinate agencies. Additionally, the practice of political appointments of top civil servants by Finnish governments that evolved during this time period may actually have strengthened their influence within the ruling political parties on this particular policy area.

Policy Entrepreneurship

Lastly, but not least importantly: there was no policy entrepreneur at cabinet level to champion agency relocations as in Norway and Sweden. This is another puzzle, since Finland had a head of state – President Kekkonen – with far more political power and leverage than the constitutional and mostly symbolic heads of state (monarchs) in Norway and Sweden. By the mid-1970s Kekkonen had through an exceptionally long-lasting presidency (1956–1981) acquired a reputation as an all-powerful president (Arter Citation[1999] 2008). He was not shy of wielding his powers on many policy issues. Nevertheless, and for whatever reason, even though he came from the Center party, he chose not to use his strong constitutional prerogatives as president to force his cabinet to adopt and implement the rather large-scale relocation program that his own party so strongly advocated. The role of unions, and in particular those organizing personnel in affected central agencies, was no doubt another major constraining factor on cabinet policy-making capability. Their politically fragmented and hence weaker organizational strength (Alvarez et al. Citation1991, p. 553) was probably more than compensated for by the quite fragile and weak governments, the many institutional veto points and the dominating presence of a labor-friendly party – the Social Democrats – in virtually all of them.

Conclusion: The Crucial Explanatory Factors

We formulated three propositions derived from our multi-theoretical framework specifying some factors and conditions that could explain why agency relocation programs either succeed or fail at the crucial policy adoption and implementation stages. Together they suggested that policy success in this respect depended on policy entrepreneurs using their skills and resources within constitutional and institutional arrangements with strong policy-making capabilities and benign situational policy contexts to fashion politically optimal program designs during the policy formulation process that would ensure their adoption and implementation.

We think our cross-national comparative and longitudinal study largely but not fully corroborates the validity of the three propositions. Sweden and Finland seem to offer the strongest confirmation here as respectively policy-facilitating versus inhibiting institutional arrangements combined with the presence or absence of policy entrepreneurs in cabinet positions within more and less beneficial policy environments all correlate clearly with their marked difference in policy performance.

Norway presents a somewhat different intermediate pattern here. The first mostly symbolic agency relocation program should, according to proposition 1 above, have been rejected by the legislators, as in Finland at the same time, rather than being adopted. The policy failure of the 1970s is also an intermediate case with relatively strong single-party minority governments but lacking a policy entrepreneur, combined with some other clear policy-inhibiting institutional arrangements (ministerial rule and responsibility principle of public administration system, and militant labor unions) and situational context. Finally, we have the unexpected and surprising Norwegian agency relocations of the 2000s, where the policy entrepreneur almost single-handedly within a relatively weak minority coalition government fashioned an optimal legislative program design – much as Wilson (Citation1973) hypothesized – operating within a given window of opportunity that was recognized and forcefully utilized. The latter case suggests the “equifinality” often observed in comparative policy research: multiple causal paths to a given policy outcome (e.g. Weaver and Rockman Citation1993). This is just one of many aspects related to the complex, dynamic and contingent nature of institutional explanations.

In Appendix we examine the potential role of some plausible, alternative and competing explanatory factors from previous comparative public policy research to those we started out with. The conclusion here is that national variations in terms of socio-economic, demographic factors as well as stable macro-political system features and public opinion cannot logically explain national differences in policy performance, thus enhancing the credibility and validity of those we have found to be the more crucial ones.

The conjunctural policy impacts of institutions, human agency and more or less random external events and parallel processes in this study point beyond traditional historical and rational choice institutionalism towards a modified expanded version of the garbage can model-inspired Multiple Stream Framework (Kingdon Citation1984; Sabatier Citation1999; Zahariadis Citation2002; Capano and Howlett Citation2009). Work in that direction has already started (Saetren Citation2013).

Relocating central agencies was an idea that entered government agendas at a time when increasing regional imbalances came to the attention of politicians and the public while adequate policy measures to deal with them were in their infancy and hence also scarce. This, combined with its potent symbolic value, made agency relocations an idea whose time had come. By the 1980s many other probably more effective regional policy measures had been adopted and implemented. Combined with legislation on workplace democracy in the public sector and other changes in the policy environment this meant that relocating agencies now was an idea whose time had passed. Nevertheless, as we saw in Norway in the 2000s, it was an idea not forgotten by its advocates patiently waiting for a new problem context to attach as a solution. This illustrates well the “garbage can” nature of this policy idea: i.e. its remarkable ability to present itself as a solution to new policy challenges. Perhaps governmental anti-terrorism policy will be the next area where relocating government agencies may appear to be a strategically opportune solution.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Harald Sætren

Harald Sætren is professor in Administration and Organization Theory in the department with the same name at the University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway.

References

- Alvarez, R. M., Garret, G., and Lange, P., 1991, Government partisanship, labor organization and macro-economic performance. The American Political Science Review, 85(2), pp. 539–556. doi:10.2307/1963174

- Andersen, J. G., 1996, Membership and Participation in Comparative Perspective. Research Report, Aalborg: Department of Economics, Politics and Public Administration, Aalborg University.

- Anton, T. J., 1969, Policy-making and political culture in Sweden. Scandinavian Political Studies, 4, pp. 88–102. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9477.1969.tb00521.x

- Arter, D., [1999] 2008, Scandinavian Politics Today (Manchester: Manchester University Press).

- Capano, G. and Howlett, M., 2009, Understanding policy change as an epistemological and theoretical problem. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 11(1), pp. 7–31. doi:10.1080/13876980802648284

- Doorenspleet, R. and Pellikaan, H., 2013, Which type of democracy performs best? Acta Politica, 48(3), pp. 237–267. doi:10.1057/ap.2012.35

- Edsta, B., 1980, Omlokaliseringens Effekter [Effects of Relocations] (Stockholm: Budgetdepartmentet).

- Elder, N., Thomas, A. H., and Arter, D., 1983, The Consensual Democracies? The Government and Politics of the Scandinavian States (Oxford: Martin Robertson).

- Elvander, N., 1974, Interest groups in Sweden. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 413, pp. 27–43. doi:10.1177/000271627441300104

- George, A. L. and Bennett, A., 2005, Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press).

- Gerring, J., 2007, Is there a (viable) crucial-case method? Comparative Political Studies, 40(3), pp. 231–253. doi:10.1177/0010414006290784

- Howlett, M., 2011, Designing Public Policies: Principles and Instruments (London: Routledge).

- Ingram, H. and Mann, D. E., 1980, Why Policies Succeed or Fail (Beverly Hills, CA: Sage).

- Isaksson, G.-E., 1989, Resultatløs Omlokalisering. [Failed Relocations] (Åbo: Åbo Academic Press).

- Karvonen, L., 1981, Med vårt västra grannland som förebild, Phd dissertation, Åbo Academy.

- Kingdon, J., 1984, Agendas, Alternatives and Public Policies (Boston, MA: Little Brown).

- Lane, J.-E. and Ersson, S. O., 1994, Politics and Society in Western Europe, 3rd ed. (London: Sage).

- Lijphart, A., 1984, Democracies. Patterns of Majoritarian and Consensus Government in Twenty-One Countries (New Haven, CT: Yale University).

- Lipset, S. M., 1990, Continental Divide. The Values and Institutions of the United States and Canada (New York: Routledge).

- Lowi, T. J., 1964, American business and public policy, case studies and political theory. World Politics, 16, pp. 677–715. doi:10.2307/2009452

- March, J. G. and Olsen, J. P., 1984, The new institutionalism: Organizational factors in political life. American Political Science Review, 78(3), pp. 734–749. doi:10.2307/1961840

- Meyer, C. B. and Stensaker, I. G., 2009, Making radical change happen through selective inclusion and exclusion of stakeholders. British Journal of Management, 20(2), pp. 219–237. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8551.2008.00562.x

- Nilsson, J.-E., 1992, Relocation of state agencies as a strategy for urban development: The Swedish case. Scandinavian Housing & Planning Research, 9, pp. 113–118. doi:10.1080/02815739208730296

- NordRefo, 1988, De Nordiska Hovudstaderna: Drivkrefter eller skapare av regional ubalans? Fem studier (Copenhagen: NordRefo report).

- Norman, V. D., 2004, Blue Notes (Bergen: Vigmostad & Bjørke).

- NOU 1977:3 Utflytting av statsinstitusjoner fra Oslo. Del II.

- Olsen, J. P., 1992, Analyzing institutional dynamics. Staatswissenschaft Und Staatspraxis, Heft, 2, pp. 247–271.

- Olsen, J. P. and Peters, B. G., 1996, Lessons from Experience. Experiential Learning in Administrative Reforms in Eight Democracies (Oslo: Scandinavian University Press).

- Peters, B. G., Pierre, J., and King, D. S., 2005, The Politics of Path Dependency: Political Conflict in Historical Institutionalism. The Journal of Politics, 67(4), pp. 1275–1300. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2508.2005.00360.x

- Petersson, O. and Valen, H., 1979, Political cleavages in Sweden and Norway. Scandinavian Political Studies, 2(4), pp. 313–332. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9477.1979.tb00226.x

- Petterson, R., 1980, Omlokalisering av Statlig Verksamhet. [Relocation of Governmental Organizations] (Stockholm: Government’s Printing Office).

- Pollitt, C. and Bouckaert, G., 2011, Public Management Reform (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

- Richardson, J. J., 1982, Policy Styles in Western Europe (London: George Allen & Unwin Hyman).

- Ripley, R. B. and Franklin, G. A., 1982, Bureaucracy and Policy Implementation (Homewood, IL: Dorsey Press).

- Sabatier, P., 1999, Theories of the Policy Process (Boulder, CO: Westview Press).

- Saetren, H., 1983, Iverksetting av Offentlig Politikk. [Implementation of Public Policy] (Bergen/Oslo: University Press).

- Saetren, H. (2013) Lost in translation: Re-conceptualizing the Multiple Streams framework back to its source of origin to enhance its analytical and theoretical leverage. ECPR joint sessions conference paper, Mainz, March.

- Saunders, P., 1985, Public expenditure and economic performance in OECD countries. Journal of Public Policy, 5(1), pp. 1–21. doi:10.1017/S0143814X00002865

- SOU 1970: 29 Decentralisering av statlig verksamhet. Rapport I.

- SOU 1972: 55 Decentralisering av statlig verksamhet. Rapport II.

- Steinmo, S., Thelen, K., and Longstreth, F., 1992, Structuring Politics: Historical Institutionalism in Comparative Analysis (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

- Stenstadsvold, K., 1975, Northern Europe, in: H. D. Clout (Ed.) Regional Development in Western Europe (London: John Wiley & Sons), pp. 245–271.

- Stinchcombe, A. L., 1968, Constructing Social Theories (New York: Hartcourt, Brace & World).

- Weaver, R. K. and Rockman, B. A., 1993, Do Institutions Matter? (Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution).

- Wilson, J. Q., 1973, Political Organizations (New York: Basic Books).

- Yin, R. K., 2009, Case Study Research: Design and Methods (London: Sage).

- Zahariadis, N., 2002, Ambiguity and Choice in Public Policy (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press).

Appendix

Table A1. Stability index score of Nordic governments 1955–1984.

Table A2. External contact patterns and contact frequencies of central agencies in Norway and Sweden in the early-to-mid 1970s.

Table A3. Factors that cannot logically explain national differences with respect to success and failure of relocation programs during the 1970s.