Abstract

Eliminating sexual harassment at work has an important role to play in accelerating progress toward gender equality in the economy. This study examines how 192 countries’ laws address workplace sexual harassment and measures the pace of change in adopting new legislation over the past five years since the #MeToo movement, during which global momentum to address sexual harassment increased. The analysis finds that an additional 13 countries now prohibit sexual harassment. Yet in 22 per cent of high-income, 26 per cent of middle-income, and 34 per cent of low-income countries, sexual harassment in the workplace remains legal. Closing these policy gaps and establishing stronger accountability mechanisms around both prohibition and prevention must be a priority.

Introduction

As of 2021, the World Economic Forum estimated that, at the current rate of progress, it would take over 267 years to achieve gender parity in the economy (World Economic Forum Citation2021). Sexual harassment in the workplace clearly contributes to these gaps. Sexual harassment can lead to high rates of employment loss both when individuals are fired by their harasser and when individuals leave a job to evade the harassment (Gutek Citation1985; McLaughlin et al. Citation2017); among those who stay at the same job, harassment contributes to absenteeism and work withdrawal (Fitzgerald et al. Citation1994; Hanisch et al. Citation1998; Willness et al. Citation2007; Chan et al. Citation2008). These economic consequences have been documented across continents (Merkin Citation2008; Merkin and Shah Citation2014). Even among those workers who stay on the job and do not display increased absenteeism, those who have been harassed can be denied training and promotion, with consequences for both the individuals and the success of the business (Australian Human Rights Commission Citation2018). Women who have been sexually harassed at work are also more likely to suffer from depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (Fitzgerald et al. Citation1997; Collinsworth et al. Citation2009; Houle et al. Citation2011; Fitzgerald and Cortina Citation2018), and are more likely to report headaches, insomnia, nausea, weight loss, and cardiovascular disease (Schneider et al. Citation2001). Collectively, the negative impact of these individual consequences on firms’ productivity and turnover can lead to poorer economic performance (Lin et al. Citation2014) as well as high productivity loss and financial cost at the national level (Jezard Citation2017; Deloitte Citation2019); taking steps to reduce sexual harassment thus matters not just for individual workers but for societies more broadly.

While no single global survey provides estimates of the frequency of sexual harassment around the world, a series of studies demonstrate the scale of the problem in high-income countries. A study carried out in 28 European Union (EU) countries found that 55 per cent of women reported having personally experienced some form of sexual harassment in their lifetime (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights Citation2014; Directorate-General for Communication Citation2016). Similarly, in the United States, 59 per cent of women reported having experienced verbal or physical sexual harassment (Graf Citation2018). Moreover, detailed studies across regions show the high prevalence of sexual harassment in workplaces globally.

These studies illustrate how sexual harassment spans not only geographies but also occupations and positions. In Kolkata, India, 74 per cent of female construction workers reported being sexually harassed at work (Rai and Sarkar Citation2012). Three in ten military women in Canada reported being individually targeted by sexualized or discriminatory behavior, and one in 20 reported being sexually assaulted (Cotter Citation2019). In Brazil, 26 per cent of domestic workers reported having experienced sexual harassment in the preceding year alone, as did 28 per cent of domestic workers in India (UN Women Citation2020). While women in male-dominated fields and in precarious work have been more widely recognized to be at high risk, sexual harassment is pervasive across social classes. A survey of lawyers in 135 countries found that one in three women had experienced sexual harassment at work (Weiss Citation2019), and a study that spanned Japan, Sweden, and the United States found that women in supervisory roles were 30–100 per cent more likely to have experienced sexual harassment in the preceding year than those in non-supervisory roles (Folke et al. Citation2020). Among female parliamentarians representing 38 countries across five continents, 33 per cent reported having experienced harassment at work and 22 per cent sexual violence (Inter-Parliamentary Union Citation2016).

Global Context and International Obligations

In 2015, all 193 UN member states unanimously adopted the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – a blueprint for improving economic, social, and environmental outcomes in all the world’s countries by 2030. The SDGs explicitly commit all countries to advancing gender equality in the economy and to ending all forms of violence and discrimination, reinforcing countries’ longstanding obligations to ensure women’s equal rights in all spheres as embodied in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations Citation1948). Specifically, SDG 5 calls on countries to eliminate all forms of gender discrimination, including through adopting new laws; to end gender-based violence; and to ensure women can access leadership positions in the public and private sector alike. Likewise, SDG 8 urges governments to “achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men”, including through equal pay, and to ensure safe working conditions for everyone.

The evidence makes clear that prohibiting sexual harassment at work is integral to addressing equal opportunities in employment and upholding decent conditions of work. Moreover, the SDGs build on a series of global agreements more specifically recognizing the importance of addressing sexual harassment in the workplace. In 1992, the UN committee charged with implementing the Convention to Eliminate All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) – an international treaty with 189 states parties as of this writing – found that “equality in employment can be seriously impaired when women are subjected to gender-specific violence, such as sexual harassment in the workplace”, and passed a General Recommendation that states parties implement “[e]ffective legal measures, including penal sanctions, civil remedies and compensatory provisions to protect women against all kinds of violence, including … sexual assault and sexual harassment in the workplace” (Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women Citation1992). Three years later, in 1995, the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, unanimously adopted by 189 countries, called on governments to “enact and enforce laws and develop workplace policies against … discriminatory working conditions and sexual harassment” (United Nations Citation1995). And in 2017, the CEDAW Committee adopted an update to its earlier recommendation defining harassment as a form of gender-based violence and urging action by both governments and the private sector (Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women Citation2017).

Regional instruments have likewise recognized the critical importance of addressing sexual harassment in employment. The European Union (Citation2002) Directive on the equal treatment of men and women at work explicitly defined sexual and sex-based harassment as discrimination, and urged employers to take preventive measures against it (European Union Citation2002). Similarly, the 2003 Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa – commonly known as the “Maputo Protocol”, which has been ratified by at least 42 of 55 countries and signed by 7 more (African Union Citation2019) – calls on governments to “[e]nsure transparency in recruitment, promotion and dismissal of women and combat and punish sexual harassment in the workplace”.

The Role of National Laws and Momentum for Legal Change

Studies from a wide range of countries have found that laws and policies prohibiting sexual harassment and other aspects of gender discrimination in employment make a difference for women’s economic outcomes. One study using data from 141 countries, for instance, found that laws prohibiting gender discrimination in employment, including those addressing sexual harassment, had a positive effect on women’s labor force participation (Del Mar Alonso-Almeida Citation2014). Likewise, country-specific studies evaluating laws prohibiting sex discrimination in employment have shown impacts for women’s pay (Beller Citation1980; Zabalza and Tzannatos Citation1985). The potential of international and regional human rights agreements to advance change at the national level depends on whether countries translate their commitments into domestically enforceable laws. Adopting corresponding laws and policies at the national level both provides a tool for workers to claim their rights and affirms countries’ intentions to ensure these rights are fulfilled in practice.

Further, beyond enabling workers to seek a legal remedy when their rights are violated, sexual harassment legislation has important signaling value, and has played a significant role in “detrivializing” sexual harassment over the past several decades (MacKinnon Citation2001; Zalesne Citation2002; Citron Citation2009). Given its instrumental and normative impacts, legal change has long been a core demand of social movements working to advance gender equality in the economy. In the twentieth century, in countries from South Africa to Australia to Israel, women’s movements prioritized advancing legislation to prohibit employment discrimination, recognizing the centrality of equal rights at work to the fulfillment of equal rights more broadly (Htun and Weldon Citation2018).

In 2017, the #MeToo movement built on this foundation and brought a surge of new global momentum to address sexual harassment worldwide: within ten days of the #MeToo hashtag gaining public visibility in the US, it had trended in 85 different countries (PBS News Hour Citation2017; Jaffe Citation2018), and the movement and its offshoots have since had documented impacts everywhere from sub-Saharan Africa (Blumell and Mulupi Citation2020) to East Asia (Hasunuma and Shin Citation2019), South Asia (Sambaraju Citation2020), and Latin America (Wessel and Pérez Ortega Citation2020). Moreover, across countries, calls for stronger laws and better enforcement of existing legislation has been a consistent theme (Stone and Vogelstein Citation2019).

Renewed momentum to address sexual harassment through the law has also come in the form of new international commitments. Two years after #MeToo launched worldwide, the International Labour Organization (ILO) adopted a long-awaited global convention specifically addressing sexual harassment at work. Unions representing workers across industries – including the International Trade Union Confederation, the International Domestic Workers’ Federation, the International Transport Workers Federation, and IndustriALL Global Union – as well as organizations like Public Services International and Solidarity Center have widely supported efforts to advance its ratification (Public Services International Citation2021; IndustriALL Citation2019; International Trade Union Confederation Citation2021).

The Importance of Monitoring Legal Change

In summary, the significant individual and societal consequences of sexual harassment on their own necessitate that countries enact laws and policies that prohibit harassment in the workplace. At the same time, the obligation to adopt effective laws addressing sexual harassment is well established by international and regional human rights agreements. Moreover, evidence suggests that these legal changes can meaningfully improve women’s economic outcomes at scale, which is essential if we are to accelerate progress toward closing the gender gaps that persist in every country rather than waiting another 267 years or longer. It is within this context that monitoring national action to address sexual harassment at work takes on new urgency.

In this study, we examine the extent to which all countries worldwide have passed laws to address sexual harassment at work comprehensively, which is critical to both fulfilling their SDG commitments and advancing gender equality more broadly. To do so, we provide data on how many countries have legal protections against sexual harassment and whether these protections explicitly prohibit the full range of forms that sexual harassment can take. We also document whether these laws require that employers take action to prevent sexual harassment, and whether workers are protected from retaliation, demotion, and losing their job and income for reporting sexual harassment or corroborating coworkers’ claims. We then examine the strength of sexual harassment laws among those countries with more longstanding or specific commitments to addressing it, whether through CEDAW and its general recommendations, the Maputo Protocol, and/or EU Directive 2002/73/EC. Finally, by measuring policy change in both protection and enforcement from 2016 to 2021, we monitor progress in strengthening sexual harassment laws in the first few years following the SDGs’ adoption in 2015, and analyze whether global momentum to address sexual harassment following the #MeToo era is accelerating progress in strengthening provisions to close gender gaps in the economy.

Methods

Data Source

To assess the extent and nature of legal protections against sexual harassment at work, we constructed a database of legal prohibitions of sexual harassment in all 193 UN member states as of January 2021. Labor acts, anti-discrimination acts, sexual offenses acts, criminal codes, and other relevant pieces of legislation, including any relevant amendments and repeals, were identified and downloaded through the International Labor Organization’s NATLEX database and country websites. We consulted the publicly available legal repositories of individual countries if the information on NATLEX was incomplete or outdated and supplemented these primary sources of legislation with secondary sources for additional countries.Footnote1

The database focuses on workplace-specific protections, but includes non-workplace-related laws – for example, penal codes – if their sexual harassment provisions clearly apply to the workplace. While sexual harassment occurs in all work settings, we only coded legislation if it applied to the private sector, where the majority of women in formal employment work (World Bank Citation2022). In some countries public sector legislation is more protective than private sector legislation, and we wanted to capture the details of those protections that applied to most women in the workforce. Some countries address sexual harassment at work in both criminal and labor laws and policies; when multiple pieces of legislation explicitly addressed sexual harassment at work or by someone in a position of authority, we coded for the most protective provision. In Sierra Leone, the Sexual Offences Act prohibits “harassment”, but defines harassment using language other countries typically use to refer to stalking. Given this inconsistency, Sierra Leone is not included in summary measures.

To assess protections against sexual harassment and obligations around prevention and enforcement, we developed a framework to capture essential features of legislation. To do so, we assessed common elements of approaches to addressing sexual harassment within global and regional agreements (for details, see ). These included CEDAW General Recommendations 19 and 35 (which provide official guidance on treaty obligations applicable to all 189 states parties); EU Directive 2002/73/EC (which is binding on all EU countries but requires national legislation to implement) (European Union Citationn.d.); and the Maputo Protocol (ratified by 42 African Union countries). We also reviewed ILO Convention 190, which represents the most recent example of global consensus on actions necessary to address sexual harassment at work and reflects the input of labor unions, employers, and governments alike. We supplemented this review of global standards with research evidence on key aspects of policy design in order to develop comparative measures. We also sought and incorporated feedback on the framework from external researchers and civil society organizations.

Table 1. Approaches global and regional instruments take to addressing sexual harassment

The framework was then tested on a subset of geographically and income-level diverse countries to ensure it adequately captured the range of approaches that countries take. A detailed codebook was then developed to ensure all coders followed the same approach for each country. From October 2020 to June 2021, for each country, an international, multilingual, multidisciplinary research team of coders with in-depth experience working in all regions analyzed the language on sexual harassment in each piece of legislation using the codebook. To ensure accuracy and minimize human error, two separate researchers read each piece of legislation; the two coders then reconciled any discrepancies in their coding decisions. If these coders could not reach consensus using the codebook, they brought the question to the full research team. If the country’s approach could not be accurately captured using the existing coding framework, the codebook was updated to accurately capture the new approach and, when needed, further checks were done to ensure previously coded countries were accurately captured by the expanded approach. Once coding was complete, we conducted in-depth quality checks for variables that were challenging during coding or for which there were concerns about consistency, randomized checks for more straightforward variables, and verifications of countries that appeared as global, regional, or income-level outliers.

Variables

Defining Sexual Harassment

Workplace sexual harassment can take a range of forms. Beyond demands for sexual favors in exchange for a job, promotion, or favorable treatment at work (i.e. “quid pro quo” harassment), behavior that creates a hostile work environment can also constitute sexual harassment. Moreover, both sexual behavior-based harassment and sex-based harassment – which is not necessarily sexual in nature, but targets women because of their sex – can have significant consequences for gender equality at work. To assess legal coverage, we first looked at which behaviors were defined as legally prohibited sexual harassment. We categorized countries as having the strongest level of protection if they prohibited both (1) quid pro quo or unwanted sexual advances and (2) the creation of a hostile work environment or behavior that violates a person’s dignity. Second, we looked at whether legislation prohibited both sexual behavior-based harassment and sex-based harassment.

Defining Who Is Prohibited and Who Is Protected

Both research and case law have amply documented that a wide range of actors can perpetrate sexual harassment in the workplace. Similarly, workers can face harassment at every stage of employment and in every type of job. Our assessment of who is prohibited from committing sexual harassment examined the extent to which laws explicitly prohibited harassment by coworkers, employers, and supervisors. Our assessment of who was legally covered by sexual harassment laws included whether laws explicitly prohibited the sexual harassment of everyone in the workplace or specifically prohibited sexual harassment of (1) job applicants or during the hiring process or (2) individuals receiving training, such as interns, trainees, or apprentices, in addition to employees. We also assessed whether provisions explicitly extended to cover sexual harassment based on sexual orientation or gender identity, given evidence that harassment based on these and related grounds is commonplace (Berkley and Watt Citation2006; Perraudin Citation2019).

Employer Prevention

While the literature rigorously evaluating the effectiveness of specific employer prevention efforts is limited, the evidence is strong that a company’s “organizational climate”, which is influenced by the preventive steps companies take, shapes the prevalence of sexual harassment in the workplace (Fitzgerald et al. Citation1994, Citation1997; Ollo-López and Nuñez Citation2018). We examined legislation to determine whether employers were required to take measures to prevent sexual harassment in the workplace. We distinguished between laws that made prevention a general responsibility for employers and those that required employers to take two specific steps explicitly mentioned in both C190 and CEDAW General Recommendation No. 35: creating a code of conduct or establishing disciplinary procedures and raising awareness, providing legal information, or requiring training.

Retaliation

Fear of retaliation can be a major barrier to reporting sexual harassment at work (Cortina and Magley Citation2003; Svensson and van Genugten Citation2013; United States Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Citation2016). We assessed whether legislation explicitly prohibited retaliation against individuals filing sexual harassment complaints. Our measures of prohibition of retaliation looked at both who is protected and the forms of retaliation that are prohibited. To understand who was protected, we looked at whether each prohibition of retaliation clearly stated who was covered, and, if it did, whether it covered only individuals who filed a complaint (internally or with an external body) or initiated litigation, or also covered workers who participated in investigations by providing evidence or testimony. To understand what forms of retaliation were prohibited, we examined whether individuals who reported sexual harassment were protected from any adverse action, whether legislation more narrowly prohibited harassment or disciplinary action (including dismissal), or whether workers were protected only from dismissal.

Analysis

All analyses were conducted using Stata MP 14.2. Differences were assessed by country income group using the Pearson’s chi-square statistics. Differences are reported when they are statistically significant. We analyzed whether the nature of protections varies by country income level. Country income level was categorized according to the World Bank’s country and lending groups as of 2020.

To assess whether legislative prohibitions have strengthened over time, we compared our results with those in place as of August 2016. For every instance of legislative change between 2016 and 2021, our research team thoroughly verified the timing and substance of legal reform to confirm that there was an actual change in the underlying legislation.

To examine whether countries that have agreed to prohibit sexual harassment at work through international or regional commitments have done so, we also analyzed the number of countries with legislative gaps that have ratified CEDAW, are members of the European Union, or have ratified the Maputo Protocol. Because C190 came into force only recently and ratification by member states is just beginning to accelerate (ILO Citation2022), we do not analyze whether national legislation is consistent with the convention, though it would be valuable to do so once countries have had more of an opportunity to adopt new laws domesticating their C190 commitments.

Results

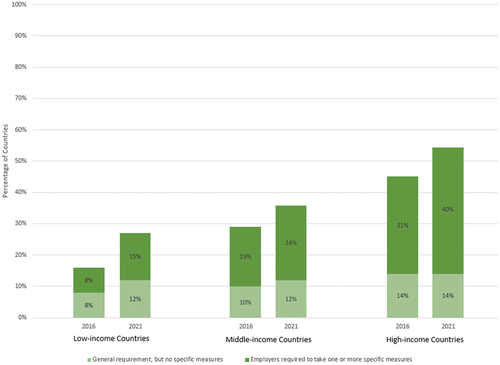

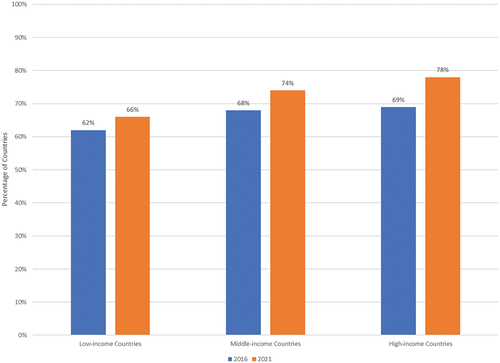

A total of 142 countries prohibit sexual harassment at work: 78 per cent of high-income countries prohibit sexual harassment at work, as do 74 per cent of middle-income countries, and 66 per cent of low-income countries (see ).

Figure 1. Percentage of countries prohibiting sexual harassment at work by country income level and year

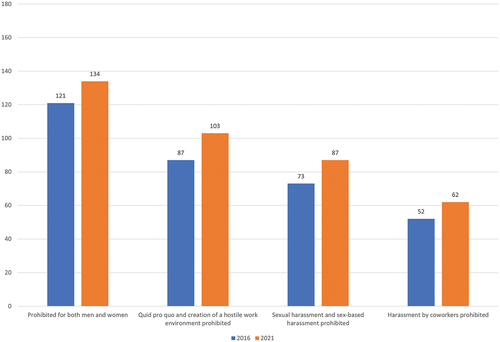

The number of countries prohibiting sexual harassment has increased over the past five years. In 2016, 121 countries explicitly prohibited sexual harassment of both men and women in the workplace; by 2021, the number explicitly prohibiting sexual harassment against both men and women increased to 134 countries (see ).

Figure 2. Number of countries with strong workplace sexual harassment prohibitions in 2016 compared to 2021

Do Laws Prohibit All Forms of Sexual Harassment?

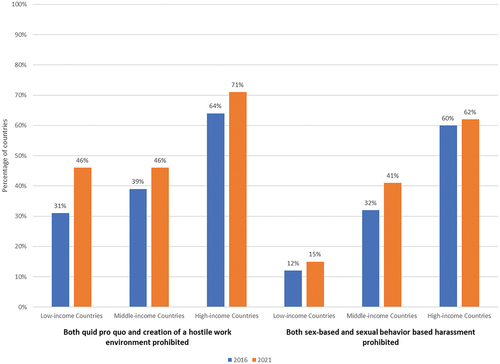

The number of countries prohibiting both quid pro quo and the creation of a hostile work environment increased from 87 in 2016 to 103 in 2021. Similarly, the number of countries prohibiting both sexual harassment and sex-based harassment increased from 73 countries in 2016 to 84 countries in 2021 (see ).

High-income countries are the most likely to specify that both quid pro quo and the creation of a hostile work environment are forms of sexual harassment. 71 per cent of high-income countries prohibit both creating a hostile work environment and quid pro quo demands compared to 46 per cent of low-income countries (p < 0.05) and 46 per cent of middle-income countries (p < 0.01) (see ).

Figure 3. Percentage of countries with strong definitions of sexual harassment in 2016 compared to 2021 by country income

While a majority of high-income countries (62 per cent) prohibit both sex-based and sexual behavior-based harassment, only 15 per cent of low-income countries (p < 0.01) and 41 per cent of middle-income countries (p < 0.01) do so (see ).

Who Is Prohibited and Who Is Protected?

Sexual harassment can be perpetrated not only by supervisors, but also by coworkers, contractors, and customers in the workplace. The number of countries with laws that prohibited sexual harassment specifically by coworkers or broadly by anyone in the workplace increased from 52 in 2016 to 62 in 2021 (see ). While in 2016, high-income countries were more likely than low-income countries to prohibit sexual harassment by coworkers (p < 0.05), there were no statistically significant differences in these protections by country income level as of 2021 (see ). In a number of cases, countries explicitly added coworkers to existing legislation. For example, Burundi, Ecuador, Ethiopia, and Niger previously covered employers and supervisors and amended legislation to also cover coworkers.

Figure 4. Percentage of countries prohibiting sexual harassment by coworkers in 2016 compared to 2021 by country income

While sexual harassment laws that clearly protect all individuals in the workplace exist in a minority of countries, full coverage is feasible: 52 countries explicitly covered job seekers and 38 countries explicitly covered interns and apprentices in 2021, as just two examples.

Protections against sexual harassment committed regardless of sexual orientation and/or gender identity likewise remain infrequent, but improvements have occurred: the number of countries prohibiting sexual harassment regardless of sexual orientation or same-sex sexual harassment increased from 31 in 2016 to 39 in 2021, and the number of countries prohibiting sexual harassment regardless of gender identity increased from 15 in 2016 to 24 in 2021.

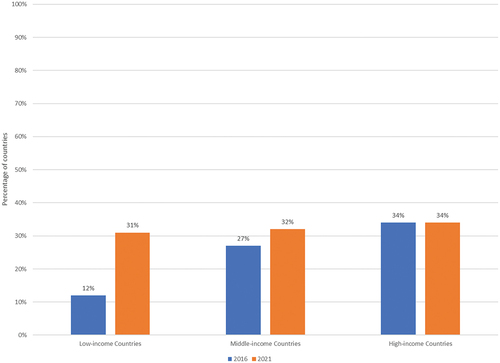

Do Employers Have a Responsibility to Prevent Sexual Harassment?

An important aspect of enforcement of these prohibitions is the role and responsibility of employers. While still only a minority, the number of countries that have laws requiring employers to take specific prevention measures such as creating policies and/or providing training on sexual harassment – as opposed to stating a general, undefined responsibility – increased from 40 in 2016 to 53 in 2021. The total number of countries requiring firms to make some prevention efforts, either general or specific, increased from 61 in 2016 to 77 in 2021. High-income countries (54 per cent) are more likely than low- (27 per cent, p < 0.05) or middle-income countries (36 per cent, p < 0.05) to legislatively require these prevention efforts (see ). In addition, 69 countries establish that employers can be held legally responsible for sexual harassment in the workplace.

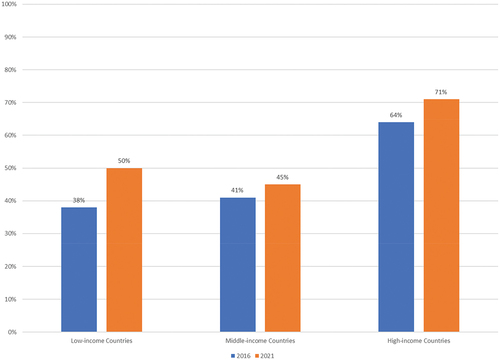

Do Laws Prohibit Retaliation against Employees Who Speak Up about Sexual Harassment?

Eighty-six countries prohibit any form of adverse action against employees for reporting sexual harassment. An additional 17 countries have narrower prohibitions of retaliation, such as only prohibiting retaliatory dismissal or disciplinary action. In 74 countries, prohibitions of retaliation extend to workers participating or assisting in investigations, regardless of whether they filed the original complaint. High-income countries are more likely to have at least some protection from retaliation for employees who report having been sexually harassed (71 per cent) than low-income countries (50 per cent, p < 0.05) or middle-income countries (45 per cent, p < 0.01) (see ). The number of countries offering some protection against retaliation to those reporting sexual harassment increased from 91 in 2016 to 103 in 2021.

Are Countries Meeting Their International or Regional Commitments to Ending Sexual Harassment at Work?

Gaps in legal prohibitions of sexual harassment at work persist even among countries that have international or regional commitments to ensuring workplaces are free from sexual harassment. Forty-five of the 187 UN member states that have ratified CEDAW have not even taken the first step of legally prohibiting sexual harassment in the workplace.Footnote2 However, countries that have ratified CEDAW are making legal progress toward realizing their international and regional commitments. Since 2016, 13 countries that have ratified CEDAW have introduced or amended their legislation to prohibit sexual harassment at work. Ratifiers have also taken steps to strengthen laws prohibiting sexual harassment over the past five years. Seventeen countries that have ratified CEDAW expanded legal prohibitions to cover conduct that creates a hostile work environment and 12 did so to prohibit sex-based harassment.

There are also gaps in coverage among Maputo Protocol ratifiers. Nine of the 42 countries that have ratified the Maputo Protocol have not legally prohibited sexual harassment at work. But there has been progress. Since 2016, four countries that have ratified the Maputo Protocol have introduced or amended legislation to prohibit sexual harassment. Several Maputo ratifiers have also improved legislation. Five countries that ratified Maputo added prohibitions of conduct that creates a hostile work environment and six countries added prohibitions of sex-based harassment.

All 27 members of the European Union have national legislation prohibiting sexual harassment at work. For all EU members, legislation also provides a strong definition, covering quid pro quo, conduct that creates a hostile work environment, and sex-based harassment. However, despite clear language in the EU directive, 12 EU countries do not explicitly prohibit sexual harassment for job seekers and 12 also fail to do so for interns, apprentices, and employees in training. Moreover, while all EU members prohibit at least some form of retaliation for reporting sexual harassment at work, five countries have no requirements for employers to take steps to prevent sexual harassment and three do not require specific steps. Over the past five years, three EU members introduced or expanded legislation to require employers to take specific steps to prevent sexual harassment.

Discussion

As the #MeToo movement spread rapidly around the world in 2017, the response from millions of women powerfully illustrated how frequently sexual harassment continued to occur in the workplace and how damaging it was. Both in countries without any legal protections and in countries where laws and policies had been inadequately enforced, women across regions and income groups recounted facing quid pro quo harassment, hostile work environments, and sexual violence, as well as the enduring health and economic consequences of these experiences. The persistence of sexual harassment across countries – and the inadequacy of governments’ efforts to address it – has stalled global progress toward achieving gender equality in the economy.

Our findings demonstrate that the gaps in national laws remain substantial. Fifty countries fail to explicitly prohibit sexual harassment at work. In 89 countries laws do not prohibit sexual harassment that creates a hostile work environment. In 105 countries sex-based harassment is not explicitly prohibited. In 130 countries laws do not ensure workers are protected from sexual harassment by their peers. Even more countries fail to ensure protection from sexual harassment for job applicants (140) and for interns, apprentices, or employees in training (154).

Moreover, shortcomings are evident across countries in all regions and income groups. While 71 per cent of high-income countries prohibit both sexual harassment in the form of quid pro quo and in the creation of hostile work environments, in 22 per cent of high-income countries sexual harassment in the workplace of every kind is not illegal. The gaps in the laws are even greater in middle- and low-income countries: 26 per cent of middle-income countries and 34 per cent of low-income countries do not prohibit sexual harassment.

Nevertheless, the numbers are improving. While 63 countries had no prohibition against sexual harassment in 2016, by 2021 that number had declined to 50. Countries that newly passed prohibitions against sexual harassment of both men and women in that five-year period included Bahrain, Barbados, Chad, Djibouti, Gabon, Monaco, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, Tuvalu, the United Arab Emirates, and Uzbekistan. Ethiopia and the Central African Republic improved their laws to cover not only sexual harassment of women but also sexual harassment of men. Lebanon and Marshall Islands passed new prohibitions but only against the harassment of women.

The scope and coverage of countries’ sexual harassment laws and policies have also improved in other ways over the past five years, though important gaps remain. For example, only a minority of countries explicitly prohibit sexual harassment based on sexual orientation and/or gender identity. However, coverage expanded from 2016 to 2021: the number of countries that explicitly prohibited sexual harassment based on sexual orientation or same-sex sexual harassment increased from 31 to 39, while the number of countries that explicitly prohibited sexual harassment based on gender identity increased from 15 to 24. Over the same period, a number of countries adopted or amended laws to newly prohibit the creation of a hostile work environment. Examples include Burkina Faso, Burundi, Ecuador, Lithuania, Niger, Sao Tome and Principe, and South Sudan.

Ultimately, for these laws and policies to have full impact, employers should have a legal obligation to prevent sexual harassment before it occurs. Yet troubling gaps in the law also persist with respect to implementation and enforcement: in more than half of countries worldwide, employers are still not required to take any preventive steps, either because sexual harassment is legal or because existing laws place no responsibility on employers. In only 28 per cent of countries are employers required to take specific steps to prevent sexual harassment. Workers can also face substantial risks if they take action themselves: in 20 per cent of countries, sexual harassment is prohibited, but employees have no protection from retaliation for speaking up when they are sexually harassed at work. Still, improvements are occurring. For example, the number of countries requiring that employers take specific measures increased from 40 in 2016 to 53 in 2021. In short, across areas there is important progress, but the gaps remain large.

These gaps persist in the presence of widespread global and regional agreements to do better. Despite long international agreement on the importance of ending discrimination at work and clear determinations that sexual harassment is discriminatory, nearly one in four countries that have ratified CEDAW have not taken the first step of legally prohibiting sexual harassment in the workplace. Moreover, effectively addressing sexual harassment is essential to fulfilling all countries’ commitments to end gender discrimination at work established by the SDGs. There are also critical gaps in adherence to regional agreements. Although all EU members have legislation prohibiting sexual and sex-based harassment at work, eight countries do not require employers to take specific steps to prevent it, despite their clear obligation to implement preventive measures established by EU Directive 2002/73/EC. Moreover, nearly a quarter of countries that have ratified the Maputo Protocol still have no legislation prohibiting sexual harassment at work.

Improving monitoring and accountability for these commitments must be a priority going forward if the recent global and national momentum around sexual harassment is to translate into enduring change. Tracking the adoption of national laws that take a comprehensive approach to preventing, prohibiting, and providing remedies for sexual harassment can provide actionable information for policymakers and advocates working to accelerate achieving gender equality at work.

This study is the first to provide data from both before the #MeToo movement and after its global spread to examine the extent to which policymakers around the world are filling legal gaps and ensuring that every country prohibits sexual harassment and takes steps to prevent it. It is also the first to provide data on the pace of countries advancing to comply with global and regional agreements. While this study begins to fill an important gap in monitoring and accountability, this study does have key limitations that need to be filled by future research. First, this study examines legal guarantees including prevention requirements and avenues for enforcement; however, studies need to examine implementation and enforcement in practice to highlight leading and lagging countries, and to link both the successes and limitations to an understanding of which laws and policies are most effective at ensuring both greater prevention and adequate remedies when harassment occurs. Second, within countries, it is critical to understand whether sexual harassment laws and policies – even those that are comprehensive on paper – are working effectively for all women across race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, migration status, and other dimensions of identity and marginalization.

Both the individual stories from around the world that have come to light amid the rising movement to address sexual harassment and the weight of the evidence base from past research clearly underscore the profound consequences that sexual harassment has on women’s economic opportunities, their career trajectories, their income, and their health. While enforceable legal prohibitions and employer obligations to prevent sexual harassment in the workplace are only some of the tools needed to eliminate sexual harassment, they are critical components both because of the normative message they send and because of their instrumental value. To realize the potential of social movements and international agreements to address one of the most longstanding barriers to women’s economic equality, it is essential to rapidly ensure that all countries have prohibitions against sexual harassment and sex-based harassment at work and have requirements for employers to take concrete steps to prevent it.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jody Heymann

Jody Heymann is Founding Director of the WORLD Policy Analysis Center (WORLD), Distinguished Professor of Public Affairs, Public Health and Medicine at UCLA and a member of the National Academy of Sciences. Heymann led the first work to create globally comparative policy measures across all 193 countries in 2000; this has grown over two decades to be the largest quantitative global policy data center.

Gonzalo Moreno

Gonzalo Moreno is a Senior Policy Analyst at WORLD, where he leads databases on constitutional rights and minimum age of marriage and contributes to the center’s work on discrimination and sexual harassment in employment, as well as monitoring UN human rights treaties. At McGill University’s Institute for Health and Social Policy, he coordinated a multinational initiative on the health effects of poverty and inequality policies.

Amy Raub

Amy Raub is Principal Research Analyst at WORLD and responsible for the translation of WORLD's comparative policy research into findings for policymakers, citizens, civil society, and researchers. Raub has been deeply involved with the development of WORLD's databases on constitutional rights, laws, and policies since 2008.

Aleta Sprague

Aleta Sprague is Senior Legal Analyst at WORLD and an attorney whose career has focused on advancing public policies and laws that address inequality. She has co-authored a range of publications examining how laws and policies shape racial, gender, and socio-economic disparities, including most recently Advancing Equality, a book evaluating approaches to protecting equal rights in 193 constitutions.

Notes

1. For example, Mercat-Burns et al. (Citation2018).

2. As noted in the Methods section, Sierra Leone, which has ratified CEDAW and the Maputo Protocol, is not included in these analyses.

References

- African Union, 2019, List of countries which have signed, ratified/acceded to the protocol to the African charter on human and people’s rights on the rights of women in Africa. Available at https://au.int/sites/default/files/treaties/37077-sl-PROTOCOL%20TO%20THE%20AFRICAN%20CHARTER%20ON%20HUMAN%20AND%20PEOPLE%27S%20RIGHTS%20ON%20THE%20RIGHTS%20OF%20WOMEN%20IN%20AFRICA.pdf ( accessed 26 May 2022).

- Australian Human Rights Commission, 2018, Everyone’s Business: Fourth National Survey on Sexual Harassment in Australian Workplaces (Canberra: Australian Government), cited in Deloitte, 2019.

- Beller, A. H., 1980, The effect of economic conditions on the success of equal employment opportunity laws: An application to the sex differential in earnings. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 62(3), pp. 379–387. doi:10.2307/1927105.

- Berkley, R. A. and Watt, A. H., 2006, Impact of same-sex harassment and gender-role stereotypes on Title VII protection for gay, lesbian, and bisexual employees. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 18(1), pp. 3–19. doi:10.1007/s10672-005-9001-8.

- Blumell, L. E. and Mulupi, D., 2020, Newsrooms need the metoo movement. Sexism and the press in Kenya, South Africa and Nigeria. Feminist Media Studies, 21(4), pp. 639–656. doi:10.1080/14680777.2020.1788111.

- Chan, D. K. S., Chow, S. Y., Lam, C. B., and Cheung, S. F., 2008, Examining the job-related, psychological, and physical outcomes of workplace sexual harassment: A meta-analytic review. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32(4), pp. 362–376. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00451.x.

- Citron, D. K., 2009, Law’s expressive value in combating cyber gender harassment. Michigan Law Review, 108(3), pp. 373–415.

- Collinsworth, L. L., Fitzgerald, L. F., and Drasgow, F., 2009, In harm’s way: Factors related to psychological distress following sexual harassment. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 33(4), pp. 475–490. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2009.01525.x.

- Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women, 1992, General recommendations adopted by the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, eleventh session, general recommendation no. 19: Violence against women. Available at https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CEDAW/Shared%20Documents/1_Global/INT_CEDAW_GEC_3731_E.pdf ( accessed 10December 2021).

- Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women, 2017, General recommendations adopted by the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, general recommendation no. 35 on gender-based violence against women, updating general recommendation 19. Available at https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CEDAW/Shared%20Documents/1_Global/CEDAW_C_GC_35_8267_E.pdf ( accessed 26 May 2022).

- Cortina, L. M. and Magley, V. J., 2003, Raising voice, risking retaliation: Events following interpersonal mistreatment in the workplace. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 8(4), pp. 247. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.8.4.247.

- Cotter, A., 2019, Sexual Misconduct in the Canadian Armed Forces Regular Force, 2018 (Ottawa: Statistics Canada).

- Del Mar Alonso-Almeida, M., 2014, Women (and mothers) in the workforce: Worldwide factors. Women’s Studies International Forum, 44, pp. 164–171.

- Deloitte, 2019, The economic costs of sexual harassment in the workplace. Available at https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/au/Documents/Economics/deloitte-au-economic-costs-sexual-harassment-workplace-240320.pdf

- Directorate-General for Communication, 2016, Special Eurobarometer 449: Gender-Based Violence (Volume A) [ electronic dataset] (Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union). Available at https://data.europa.eu/data/datasets/s2115_85_3_449_eng?locale=en ( accessed 3September 2021).

- European Union, n.d. Types of legislation. Available at https://european-union.europa.eu/institutions-law-budget/law/types-legislation_en ( accessed 26May 2022).

- European Union, 2002, Directive 2002/73/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 September 2002 amending Council Directive 76/207/EEC on the implementation of the principle of equal treatment for men and women as regards access to employment, vocational training and promotion, and working conditions. Official Journal Law, 269, pp. 0015–0020, 5October.

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2014, Violence against Women: An EU-Wide Survey (Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union). Available at https://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2014/violence-against-women-eu-wide-survey-main-results-report ( accessed 3September 2021).

- Fitzgerald, L. F., Hulin, C. L., Drasgow, F., 1994, The antecedents and consequences of sexual harrassment in organizations: An integrated model, in: G. P. Keita and J. J. Hurrell Jr. (Eds) Job Stress in a Changing Workforce: Investigating Gender, Diversity, and Family Issues (Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association), pp. 55–73. doi:10.1037/10165-004.

- Fitzgerald, L. F., Drasgow, F., Hulin, C. L., Gefland, M. J., and Magley, V. J., 1997, Antecedents and consequences of sexual harassment in organizations: A test of an integrated model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(4), pp. 578–589. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.82.4.578.

- Fitzgerald, L. F. and Cortina, L. M., 2018, Sexual harassment in work organizations: A view from the 21st century, in: C. B. Travis, J. W. White, A. Rutherford, W. S. Williams, S. L. Cook, and K. F. Wyche (Eds) APA Handbook of the Psychology of Women: Perspectives on Women’s Private and Public Lives (Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association), pp. 215–234.

- Folke, O., Rickne, J., Tanaka, S., and Tateishi, Y., 2020, Sexual harassment of women leaders. Daedalus, 149(1), pp. 180–197. doi:10.1162/daed_a_01781.

- Graf, N., 2018, Sexual Harassment at Work in the Era OF #METOO (Pew Research Center’s Social & Demographic Trends Project). 4April. Available at https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2018/04/04/sexual-harassment-at-work-in-the-era-of-metoo/

- Gutek, B. A., 1985, Sex and the Workplace (San Francisco: Jossey–Bass). cited in O’Connell, C. E., and Korabik, K., 2000, Sexual harassment: The relationship of personal vulnerability, work context, perpetrator status, and type of harassment to outcomes, Journal of Vocational Behavior, 56(3), pp. 299–329.

- Hanisch, K. A., Hulin, C. L., and Roznowski, M., 1998, The importance of individuals’ repertoires of behaviors: The scientific appropriateness of studying multiple behaviors and general attitudes. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 19(5), pp. 463–480. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(199809)19:5<463::AID-JOB3899>3.0.CO;2-5.

- Hasunuma, L. and Shin, K., 2019, #MeToo in Japan and South Korea: #WeToo, #WithYou. Journal of Women, Politics & Policy, 40(1), pp. 97–111. doi:10.1080/1554477X.2019.1563416.

- Houle, J. N., Staff, J., Mortimer, J. T., Uggen, C., and Blackstone, A., 2011, The impact of sexual harassment on depressive symptoms during the early occupational career. Society and Mental Health, 1(2), pp. 89–105. doi:10.1177/2156869311416827.

- Htun, M. and Weldon, S. L., 2018, The Logics of Gender Justice: State Action on Women’s Rights around the World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). doi:10.1017/9781108277891.004.

- IndustriALL, 2019, Our future, our union—IndustriALL women’s conference demands transformative agenda. 21November. Available at http://www.industriall-union.org/our-future-our-union-industriall-world-womens-conference-demands-transformative-agenda ( accessed 7September 2021).

- International Labour Organization, 2022, Ratifications of C190 - Violence and harassment convention, 2019 (No. 190). Available at https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:11300:0::NO::P11300_INSTRUMENT_ID:3999810 ( accessed 26May 2022).

- International Trade Union Confederation, 24 June 2021, #RatifyC190 without delay. Available at https://www.ituc-csi.org/ratifyc190-without-delay ( accessed 7September 2021).

- Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2016, Sexism, Harassment, and Violence against Women Parliamentarians (Geneva: Inter-Parliamentary Union). Available at https://www.ipu.org/resources/publications/issue-briefs/2016-10/sexism-harassment-and-violence-against-women-parliamentarians ( accessed 20September 2021).

- Jaffe, S., 2018, The collective power of #MeToo. Dissent, 65(2), pp. 80–87. doi:10.1353/dss.2018.0031.

- Jezard, A., 21October 2017, Why we need to calculate the economic costs of sexual harassment. World Economic Forum. Available at https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/10/why-we-need-to-calculate-the-economic-costs-of-sexual-harassment/

- Lin, X., Babbitt, L., and Brown, D., 2014, Sexual Harassment in the Workplace: How Does It Affect Firm Performance and Profits? Better Work Discussion Paper Series, No. 16. Available at https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_norm/—relconf/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_553577.pdf ( accessed 21 September 2021).

- MacKinnon, C. A., 2001, The logic of experience: Reflections on the development of sexual harassment law. Georgetown Law Journal, 90, p. 813.

- McLaughlin, H., Uggen, C., and Blackstone, A., 2017, The economic and career effects of sexual harassment on working women. Gender & Society, 31(3), pp. 333–358. doi:10.1177/0891243217704631.

- Mercat-Burns, M., Oppenheimer, D. B., and Sartorius, C., 2018, Comparative Perspectives on the Enforcement and Effectiveness of Antidiscrimination Law (New York: Springer).

- Merkin, R. S., 2008, The impact of sexual harassment on turnover intentions, absenteeism, and job satisfaction: Findings from Argentina, Brazil, and Chile. Journal of International Women’s Studies, 10, pp. 73–91.

- Merkin, R. S. and Shah, M. K., 2014, The impact of sexual harassment on job satisfaction, turnover intentions, and absenteeism: Findings from Pakistan compared to the United States. SpringerPlus, 3(1), pp. 1–13. doi:10.1186/2193-1801-3-215.

- Ollo-López, A. and Nuñez, I., 2018, Exploring the organizational drivers of sexual harassment: Empowered jobs against isolation and tolerant climates. Employee Relations, 40(2), pp. 174–192.

- PBS News Hour, 2017, Twitter chat: What #MeToo says about sexual abuse in society. Available at https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/twitter-chat-what-metoo-says-about-sexual-abuse-in-society.

- Perraudin, F., 2019, Survey finds 70% of LGBT people sexually harassed at work. The Guardian, 16May. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2019/may/17/survey-finds-70-of-lgbt-people-sexually-harassed-at-work.

- Public Services International, 15March 2021, For a world of work free from violence and harassment. Available at https://publicservices.international/campaigns/for-a-world-of-work-free-from-violence-and-harassment?id=5676&lang=en ( accessed 3September 2021).

- Rai, A. and Sarkar, A., 2012, Workplace culture and status of women construction labourers; A case study in Kolkata, West Bengal. Indian Journal of Spatial Science, 3(2), pp. 44–54.

- Sambaraju, R., 2020, I would have taken this to my grave, like most women: Reporting sexual harassment during the #MeToo movement in India. Journal of Social Issues, 76(3), pp. 603–631. doi:10.1111/josi.12391.

- Schneider, K. T., Tomaka, J., and Palacios, R., 2001, Women’s cognitive, affective, and physiological reactions to a male coworker’s sexist behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31(10), pp. 1995–2018. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2001.tb00161.x.

- Stone, M. and Vogelstein, R., 2019, Celebrating #MeToo’s global impact. Foreign Policy. 7 March. Available at https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/03/07/metooglobalimpactinternationalwomens-day/.

- Svensson, J. and van Genugten, M., 2013, Retaliation against reporters of unequal treatment: Failing employee protection in The Netherlands. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 32(2), pp. 129–143. doi:10.1108/02610151311324370.

- UN Women, 2020, Sexual harassment in the informal economy: Farmworkers and domestic workers. Available at https://www.unwomen.org/-/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2020/discussion-paper-sexual-harassment-in-the-informal-economy-en.pdf?la=en&vs=4145 ( accessed 20September 2021).

- United Nations, 1948. Universal declaration of human rights. Available at https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights ( accessed 27September 2021).

- United Nations, 1995, Beijing platform for action 178(c). Available at https://www.un.org/en/events/pastevents/pdfs/Beijing_Declaration_and_Platform_for_Action.pdf ( accessed 27September 2021).

- United States Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 2016, Select task force on the study of harassment in the workplace. Available at https://www.eeod.gov/select-task-force-study-harassment-workplace#_Toc453686303 (accessed 29July 2022).

- Weiss, D. C., 16 May 2019, Bullying and sexual harassment ‘are rife in the legal profession,’ global survey finds. ABA Journal. Available at https://www.abajournal.com/news/article/bullying-is-rife-in-the-legal-profession-while-sexual-harassment-is-common-global-survey-finds.

- Wessel, L. and Pérez Ortega, R., 2020, #MeToo moves south. Science, 367(6480), pp. 842–845. doi:10.1126/science.367.6480.842.

- Willness, C. R., Steel, P., and Lee, K., 2007, A meta‐analysis of the antecedents and consequences of workplace sexual harassment. Personnel Psychology, 60(1), pp. 127–162. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00067.x.

- World Bank, 2022, Public sector employment, as a share of total employment. Available at https://govdata360.worldbank.org/indicators/haa733075?country=BRA&indicator=42305&viz=line_chart&years=2000,2017 ( accessed 24May 2022).

- World Economic Forum, 2021, Global gender gap report 2021. Available at https://www.weforum.org/reports/global-gender-gap-report-2021/

- Zabalza, A. and Tzannatos, Z., 1985, The effect of Britain’s anti-discriminatory legislation on relative pay and employment. The Economic Journal, 95(379), pp. 679–699. doi:10.2307/2233033.

- Zalesne, D., 2002, Sexual harassment law in the United States and South Africa: Facilitating the transition from legal standards to social norms. Harvard Women’s Law Journal, 25, p. 143.