Abstract

It is increasingly recognized that various competencies are needed for education systems in the developing world to succeed in fulfilling SDG4. However, reform efforts are often hampered by a lack of conceptual clarity regarding what these competencies are and how they matter. This article fills the gap by developing a comprehensive conception of policy capacity to explain the educational outcomes in two states in Brazil. The comparative case analysis reveals how variations in analytical, operational and political capacity are the differentiating factor behind their variegated reform effectiveness. While these findings put a cautionary note over the viability of copying policy interventions without considering their capacity underpinnings, they also show how a synergized combination of these three dimensions of capacity can lead to remarkable improvement of educational outcomes despite unfavorable socioeconomic conditions.

1. Introduction

Improving public service delivery has been an extensively pursued goal, and a persistent policy challenge for many developing countries. In the basic education sector, for example, there has been a mixed record regarding the effectiveness of education reforms of various kinds in boosting student learning (Masino and Niño-Zarazúa Citation2016). Education systems which are consistently regarded as successful are mostly from developed countries such as Singapore and Finland. If their advanced level of socioeconomic development is what drives good performance, then the lessons from which developing countries can draw will be limited. In explaining the high performance of these systems, existing studies have primarily focused on what the system has or what it believes (e.g. Tan Citation2018; Hwa Citation2020). Albeit insightful, it is less clear how these accounts can feed into concrete policy actions, which would necessitate a comprehensive grasp of what the system does and how it gets tasks done, i.e. the more manipulable elements which are of key concern to the study of policy design (Peters Citation2022).

To offer these insights and more relevant lessons for education reforms in the developing world, this article develops a comprehensive framework of policy capacity needed for the effective design and implementation of education system reforms and applies it to comparatively examine the cases of Ceará and Rio Grande do Norte, two neighboring and socioeconomically underdeveloped states in one of Brazil’s poorest regions. Whereas Ceará has seen remarkable improvement over the last two decades in both the quality and equity dimensions of student learning outcomes, the performance of the basic education sector in Rio Grande do Norte still lags behind. As these two states are similarly marked by low levels of socioeconomic development, conventional explanations along the lines of level of resources cannot provide a convincing explanation for this stark contrast. Through extensive exploration and examination of policy documents, existing literature, secondary datasets and supplementary consultation with key experts, our analysis unpacks the variations of capacity along the analytical, operational and political dimensions that underpin the design and implementation of their respective reforms. These variations jointly account for the outcomes of their variegated education system reforms and suggest a nuanced picture of how analytical and political dimensions of policy capacity may underlie the operational dimension.

In providing this alternative explanation that focuses on system-level capacity, this article contributes to a burgeoning literature in public policy and administration which underscores the usefulness of the policy capacity concept in accounting for policy effectiveness (see Mukherjee et al. Citation2021 for a systematic review) with a fresh case study from the education policy sector. Within the smaller literature of social policy design (Chindarkar et al. Citation2022), earlier works have either focused on a specific aspect of the education system (e.g. Yan and Saguin Citation2021 on teacher capacity development) or used a policy capacity lens to comprehensively assess reforms in other social service sectors (e.g. Bali and Ramesh Citation2019 on healthcare reforms). To our knowledge, this study is the first attempt to develop a holistic and synthesized framework of policy capacity to understand education reforms at the system level. Furthermore, we add a timely study to the still-emerging policy capacity literature on Latin America (Haque et al. Citation2021). Finally, compared with drawing lessons from high-performing education systems in developed countries, lessons generated herein may be more relevant for other developing countries to contemplate and adapt.

The remainder of the article is organized as follows. The next section introduces the theoretical framework, which is followed by methodological specifications. We then report and subsequently discuss our findings before concluding with the policy implications.

2. Theoretical Framework

Over the last few decades, education reforms have taken place across numerous parts of the developing world. With substantial progress made on universalizing school education, reforms since the beginning of the century have increasingly shifted the focus from expanding schooling access to improvement of the quality and equity of basic education. To fulfill these latter goals, which later became the key imperatives of the fourth sustainable development goal (SDG4),Footnote1 different types of reform have been introduced, often as standalone measures or with limited combinations. Examples include but are not limited to introducing teacher performance pay, recruiting non-civil-service teachers, reducing class size and increasing various other inputs.

As most of these reforms have shown variegated and largely unimpressive results in raising student learning outcomes (Masino and Niño-Zarazúa Citation2016), there has recently been a renewed interest in reforms directed at the entire education system, although the system approach in education is “still in its infancy” when compared with other sectors of public service delivery such as health or infrastructure (Mansoor and Williams Citation2018). Essentially, rather than being confined to a brief period, on a limited scale or with a narrow agenda, system-wide reforms are more likely to involve continued efforts that span a longer timeline in order to address system weakness and create a momentum for continuous improvement. Instead of a single-shot measure, these efforts are more likely to have multiple individual reforms as their constitutive components. However, for system reforms to be effective, it is important that these components are tied in a complementary and interlinked rather than piecemeal manner, so that “the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.”

In light of the complexities within education systems and the involvement of diverse stakeholders with varying interests, incentives and capacities (Bruns et al. Citation2019), creating such synergy is far from easy. Indeed, it has long been recognized that education system reforms are difficult to pull off (Saguin and Ramesh Citation2020). This suggests that compared with individual reform measures such as privatization or school-based management, for which private and civil society stakeholders may act as a driving force, system reforms would demand that a steering role be played by the government (Yan Citation2019b). Meanwhile, a substantial amount of competencies and skills are required of the government for it to navigate and steer through these complexities while designing and implementing reforms effectively towards improving student learning outcomes.

Understanding policy success and failure has been a primary motivation for studies of policy capacity (Brenton et al. Citation2022), and the extant literature has already shed light on various aspects of such capacity and how they matter. For example, Grindle (Citation2004) highlighted the role of reform mongers and policy entrepreneurs in education system reforms in Latin America in the 1990s. Saguin and Ramesh’s (Citation2020) case study attributed the lackluster results of reforming the education system in the Philippines to the neglect by reform initiators of critical governance functions such as designing appropriate policy tools and gathering political support. Baxter (Citation2020) further underscored the positive reinforcing effect of system-level trust in building capacity for improvement in education systems. However, to date, there is yet to be an effective synthesis of these insights that can offer a comprehensive understanding of policy capacity pertaining to education system reforms.

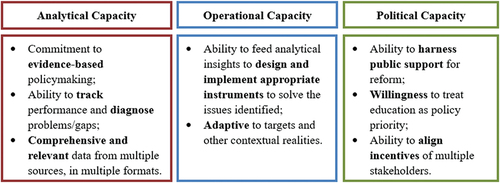

Building on these earlier works and guided by the conceptualization of policy capacity in the recent literature on policy design, as “the set of skills and resources – or competencies and capabilities – necessary to perform policy functions” along analytical, operational and political dimensions (Wu et al. Citation2015), we present in the remainder of this section such a synthesized framework of the policy capacity that is needed to make system-wide education reforms work. As illustrated in , furnishing analytical capacity usually requires a broad, systemic commitment to evidence-based policymaking that is concretely translated into a comprehensive and relevant set of information which captures the status and trend of a given sector. This is not only helpful for keeping track of the full picture of system performance and progress, but also serves as important sources of diagnosing the problems and gaps. For these purposes to be aptly fulfilled in the context of education reforms, information needs to encompass a series of topics from inputs of different sorts to outcomes in diverse formats (Yan and Saguin Citation2021).

Figure 1. Theoretical framework

Next, operational capacity is required of the system to feed the insights thus generated into concrete policy actions by transforming static informational, fiscal, physical and human resources of the system into appropriate “instruments-at-work” to proactively solve the problems identified. Rather than unhelpfully upholding the artificial dichotomy between design and implementation, a system with high operational capacity would anticipate implementation challenges and address them through the formulation of innovative, adaptive and context-sensitive policy tools (Bali and Ramesh Citation2018; Howlett et al. Citation2020).

Analytical and operational capacity needs to be accompanied and synergized with political capacity which enables the system to harness public support for reforms through legitimacy and trust (Mukherjee et al. Citation2021). System-wide education reform efforts especially demand that political leaders and policymakers, both within and beyond the education sector, hold a commitment and willingness to treat the improvement of education as a priority. Its fulfillment is far from easy though, as the sector often needs to compete with other sectors for an already limited pool of resources in developing countries. This is complicated by the specific feature of education services, whose quality and efficiency can be difficult to judge (especially when the system lacks analytical capacity), which further limits its prominence on the political agenda (Batley and Mcloughlin Citation2015). Even when resources and capabilities are available for education reforms, they can be deployed in a manner that deviates from public value creation (e.g. Hallak and Poisson Citation2005). Once these obstacles are overcome and political will is present, the system then needs the capacity to align diverse interests of stakeholders and ensure that their respective efforts are concentrated towards the policy goal (Yan Citation2019a). This is important for basic education not only because of the increasing shift from top-down to network governance of the sector, but for systems with multiple levels of government jointly responsible for education, its governance may even become a “complex intergovernmental problem” (El Masri and Sabzalieva Citation2020). In that case, such responsibilities may end up being left unattended altogether.

3. Research Methods

3.1 Rationale of Case Selection

The framework introduced in the previous section will be used to analyze and compare the education reform experience and outcomes in two states in Brazil, the largest developing country in Latin America. Like many other developing countries, Brazil has recorded lackluster and uneven progress in improving student learning despite great achievements in universalizing schooling access since the late 1990s (Gomes et al. Citation2020).

Apart from being geographically adjacent along Brazil’s northeast coastlines (see Figure A1 in the appendix), both Ceará (CE hereafter) and Rio Grande do Norte (RN hereafter) are predominantly covered by semi-arid land and face severe challenges regarding water supply. These challenges both result and are reflected in their poor socioeconomic development at a level way below the national average (see in the appendix). They are also subjected to a common set of national education policies and federal-level financing arrangements.Footnote2

Notwithstanding these similarities, educational outcomes in the two states have exhibited substantial variations: in the latest (2019) results of the Basic Education Development Index (Ideb), a synthetic indicator developed by Brazil’s Ministry of Education (MEC) that contains student assessment results, as well as failure, success and dropout rates,Footnote3 CE ranks as one of the top-performing states in the country, while RN is one of the worst-performing states. This contrast is remarkable when considering that in 2005, the benchmarking year in which Ideb results were first available, CE and RN shared very close scores (2.8 and 2.5 respectively) that were both below the national average (3.6). As demonstrated in in the appendix, their gap in 2019 was the continuation of a consistent trend for over a decade, rather than a one-time coincidence.

Not only has basic education in CE seen the greatest improvement in quality over the past two decades, but the state also managed to progress on the equity dimension, as its average grade of students from schools in the lowest socioeconomic quintile in 2017 is the highest in the country. In contrast, the average grade of their counterparts in RN is only better than two other states.Footnote4 This contrast in educational performance is further reflected in the latest round of (the only two) National Literacy Assessment results in 2016, as well as the change in enrollment patterns of primary and secondary schools between 2000 and 2020, in which CE exhibits a much more modest trend of increase in private school enrollment as an alternative to government schools (see ). To summarize, whereas RN’s education system represents a typical case in the region whose performance largely mirrors its lackluster socioeconomic development, CE’s education system can be considered as a deviation, with its remarkable performance against socioeconomic odds.

Before presenting our alternative explanation in the next section, we have first considered what other possible explanations for this variation might be. As socioeconomic development and availability of fiscal or human resources are two common factors examined in other comparative studies whose research design is similar to ours (e.g. Mangla Citation2015), it is reasonable to investigate how CE and RN differ on those dimensions in particular.

As is shown in , although the population size of CE (as per the latest population estimate) is 2.6 times of that of RN, it only has 17 more municipalities. The average size of population that needs to be served in each municipality may thus be much greater in the case of CE, though in terms of student–teacher ratios, the two states do not differ much. RN is the state with slightly more resources when it comes to GDP per capita and public expenditure per student too. As for the size of government, the number of state public servants is much higher in CE, understandably due to its larger population. Yet when counting state public servants per 1,000 inhabitants, RN again outnumbers CE by four people on average. Taken together, CE and RN do not differ substantially in terms of geography, levels of human development and average teacher supply, whereas on the dimensions where they do differ, it is CE that is facing more demographic pressure and fewer financial and human resources in general, although the difference in the latter items is not huge either. As such, these factors could not shed an adequate and coherent light on the observed divergence in educational outcomes between CE and RN.

3.2 Data and Analysis

Our comparative analysis relies primarily on the policy documents of these two states, including strategic plans, acts, regulations, government reports and so forth. To access these documents, we searched the official websites of the CE State Secretariat of Education (SEDUC-CE) and its counterpart, SEEC-RN.Footnote5 Unlike the readily available information for CE, we only find some policy reports covering 2015–2018 and the government’s strategic planning documents from RN’s website (Plano Plurianual – PPA, which contain policy initiatives it intends to develop in the next four years as required by law). Additional documents from RN’s Court of Accounts website were then examined, although they are similarly scarce.Footnote6 Still, reviewing these documents helped us gain an overall picture about the timeline of their respective reforms over the last few decades. Building on this overall picture, we then applied our theoretical framework to make sense of the varying presence or absence of policy capacity in the two education systems in effectively designing and delivering the reforms.

Besides identifying manifestations of analytical, operational and political capacity in policy documents, we have extensively searched research papers (in Portuguese) on the Brazilian Scielo (Scientific Electronic Library Online) and Capes thesis repository portals alongside the English sources, as well as documents produced by non-governmental organizations. Additional insights on RN’s reform experience and policy capacity were sought through consulting two former secretaries of SEEC-RN in June 2019 during their participation in a local seminar (for more details, see Silva Citation2020) to compensate (at least partially) for the state’s limited written records. Lastly, we analyzed administrative datasets from National Institute of Educational Research (INEP), which is responsible for the annual Educational Census and organization of national student assessments. Combined with the abovementioned sources, they gave further information not only about policies on paper, but also how they were operationalized and with what kind of results.

Two limitations need to be acknowledged regarding our empirical strategy. First, in treating policy capacity as the “independent variable” so to speak, we aim to investigate how the variations in policy capacity have shaped diverging educational outcomes between CE and RN along their distinctive reform experiences. How policy capacity is created and augmented, albeit an equally important inquiry, remains largely a “black box” that cannot be fully opened through this study. The main limitation of data is that even the more detailed record of policy documents (as in CE), as well as other secondary data that is currently available, does not contain a thorough map-out of all decision-making and deliberating activities behind each policy initiative, let alone the temporal or logical connections between them. Acquiring such information would necessitate in-depth interviews with key stakeholders who have advised or directly participated in these reforms, so that within-case process-tracing can be performed to reveal the dynamic causal processes of policy capacity development that links reform measures and outcomes.Footnote7 Interviewing individual experts involved in the reform process, when complemented by existing accounts of system-level capacity, would further help us gain a better understanding of the dynamic relationship among individual, organizational and system levels of capacity.Footnote8 Second, relying primarily on existing documents and literature means that our analysis cannot pay adequate attention to how reform measures were experienced and perceived on the ground. Again, in-depth interviews and focus group discussions with key stakeholders would help facilitate a rich and more nuanced account of actual reform practice, which can be used to further compare whether that is similar or divergent from what was suggested on paper.

4. Findings

4.1 Reform Initiatives

This section presents an overview of the reform initiatives in the education systems of CE and RN respectively (), which serves as a basis for scrutinizing the policy capacity underpinning their respective reform design and implementation and how it has ultimately contributed to their variegated educational outcomes.

Table 1. Timeline of education reforms in CE and RN

In the case of CE, the SEDUC-CE established the Regional Education Development Centers (CREDE) in 1995. While establishing this kind of regional units was common among State Secretariats of Education in Brazil as a means to facilitate communication between the secretariats and the state-owned schools,Footnote9 what makes CE’s practice stand out apart from its early establishment is that CREDE is explicitly and actively involved in supporting municipalities in implementing state programs on teacher training and school monitoring.

For student assessment, it should first be noted that results of the national-level Saeb are released on a bi-annual basis. Hence, instead of passively waiting, CE implemented its own Permanent Educational Evaluation System (Spaece) in 1992, only two years after Saeb was launched. Spaece initially covered only primary schools in the capital city of CE, but was gradually expanded to include all government schools at all levels. Further expansion was made in 2007 to include year-end literacy evaluation (Spaece-Alfa), which provided a more specific measurement of school and municipality performance towards the literacy target. These were also used to plan in-service teacher training. Alongside Spaece-Alfa, another learning diagnostic test of language and mathematics in the municipalities, taken at the beginning of the school year, aimed to create classroom- and student-disaggregated information (Bonamino et al. Citation2019). Here, the state prepared exam papers and a digital platform for results collection, while the municipalities execute the test and upload the results (Loureiro et al. Citation2020). The results of both assessments were used for planning subsequent teacher training.

There were also initiatives for raising visibility and awareness about child illiteracy in CE municipalities. In 2004, a former municipal secretary of education at Sobral, a countryside city of CE which managed to “turn around” the performance of its education system through reforms (Sumiya Citation2015), was elected to CE’s legislative assembly. Soon after his election, the secretary set up Ceará’s Committee for the Elimination of School Illiteracy (CCEAE), an initiative developed in partnership with UNICEF and the Association of Municipal Education Leaders and received support from SEDUC-CE, the MEC, local universities, Ceará’s Mayor Association and teachers’ unions.

In 2007, a newly elected state government further upgraded the effort with the launch of the Literacy at the Right Age Program (PAIC), a program developed in partnership with municipal secretariats of education to improve literacy, that was later expanded to include other subjects and grades of primary education. All municipalities in CE signed an agreement with SEDUC-CE to implement PAIC (Sumiya et al. Citation2017), which is remarkable considering that SEDUC-CE cannot impose municipal adoption of PAIC in light of the latter’s autonomy as granted by the Brazilian Constitution. Within this process, SEDUC-CE established a standardized student learning assessment to help municipalities identify their baseline and define individualized targets to be achieved through their participation in PAIC (Loureiro et al. Citation2020, p. 10). In the same year, Law 14.023/2007 was passed to change the formula for transferring state consumption tax (ICMS) to municipalities. Redistribution before the change was based on population size and municipal expenditure on education, together with a portion evenly distributed among municipalities. After the change, educational performance of the municipalities was factored in and carried the greatest weight. In 2009, a program called Escola Nota 10 was launched to reward and encourage the sharing of good practices at the school level.

Contrary to this continued record of reforms in CE, reforms in RN were marked by much lower frequency, concreteness and consistency (see ). To illustrate, despite the plans to grant autonomy to state-managed schools, as shown in RN’s Basic Education Plan (1994–2003), we did not find any available documents that formalized such plans or evaluated its implementation. There was little mention of its own programs in all five publicly available RN PPA either. Education policy actions in RN are mainly dependent on federal programs and grants such as the Adult Illiteracy Program (Brasil Alfabetizado). However, no clear results or policy evaluation reports were found in official portals. Furthermore, although the regional units in RN (DIRED) were recreated in 1999 after four years of closure, unlike their counterparts in CE, they were only responsible for state-run schools. The scarcity of mentioning state-level assessment programs is particularly in contrast with many other states, including CE, which have devised their own assessment systems. According to RN government’s website, an assessment system (SIMAIS) was initiated in 2016, with assessments carried out in 2017 to 2019, but only for state schools. Rather than being made public, the results were available only to participating schools. SIMAIS was discontinued in 2020, making RN one of the last states in Brazil without its own assessment system.

Both the State Basic Education Plan and PPA mentioned decentralization of primary schools to the municipal level as a goal for RN’s education policy, but there was no reference to the need to include municipal schools in state programs. This looks in line with findings from Silva (Citation2020) that RN has one of the lowest levels of cooperation between state and municipality in education policy and administration, whereas CE has one of the highest levels of cooperation in Brazil. RN’s lack of coordination may be particularly detrimental as 83 percent of its municipalities have a population of fewer than 20,000 inhabitants, suggesting the small size of municipal government schools in terms of student enrollment and potentially weak capacity to utilize autonomy fruitfully. RN’s more recent Basic Educational Plan (2015–2025) and the 2019–2022 PPA mentioned improvement in the quality of state schools, but again without a clear implementation roadmap.

4.2. Unpacking Policy Capacity (or the Lack Thereof)

4.2.1. Analytical Capacity

Variation of analytical capacity is first exhibited through the contrast between CE’s comprehensive data infrastructure, which potentially serves as a solid evidence base for subsequent policy actions, and RN’s lack of similarly sophisticated data generation and analysis apparatus. Probing deeper behind this picture, an attitudinal difference can be discerned in which RN’s state government mainly viewed data as presenting a negative picture about the education system without fully appreciating its usefulness in aiding the monitoring and evaluation of the progress and problems of (especially municipal) schools and the design of other policy instruments. In contrast, although the diagnosis from CCEAE in 2004 exposed that 39 percent of Grade 2 students in CE’s municipal primary schools were incapable of reading and writing, this gloomy message was proactively taken as a wake-up call in signaling the severity of the issue (McNaught Citation2022), which both pushed and informed subsequent measures to address it.

Besides this attitudinal difference, a more fundamental gap regarding analytical capacity lies in the availability of expertise within the two systems. For CE, many state–government staff behind its analytical and evaluative apparatus were from specialized government institutions (such as Economic Research Institute of Ceará for the redesign of ICMS; Loureiro et al. Citation2020, p. 17). They were either renowned for expertise in education, economics and public policy, or accumulated professional knowledge and experience through earlier reforms in Sobral (Sumiya Citation2015; Vieira et al. Citation2019). This competence enabled them to develop, through a series of reforms since the 1990s, a system consisting of diverse and complementary data rather than relying solely on data collected at the federal level that are marked by lower frequency and poorer timeliness. The annual literacy assessment as part of Spaece-Alfa, for example, had roots directly from the earlier experience of Sobral (McNaught Citation2022). As the data infrastructure was maintained and strengthened over time, it further contributed to the education system’s capacity to keep better and more regular track of the performance and progress across student, classroom, municipality and state levels, thereby suggesting a virtuous cycle between analytical capacity and education reforms.

For RN, in contrast, two former education secretaries commented during their participation in a local seminar that SEEC-RN lacked systematic process and criteria for hiring qualified staff with knowledge in management. Hence, unlike CE in which external expertise from international or non-governmental organizations largely played a supplementary role, these external sources of expertise became the very few alternatives for RN to generate key insights on the status, progress and problems of the education system. An example in this regard was the partnership between UNICEF and a flagship federal university in RN in 2007 for assessing student literacy in municipal schools. Yet despite the recruitment of alternative expertise, learning from this initiative was never meaningfully engaged and reflected in subsequent state or municipal governmental agenda as outlined in the state’s policy documents (Sumiya Citation2015).

4.2.2. Operational Capacity

The variations of operational capacity between the two states are first reflected in their different takes on illiteracy. In RN, it was understood as a problem to be addressed exclusively in adult education. Although this led to 47.4 percent and 57 percent increases in adult enrollment at municipal and state schools respectively between 2000 and 2020, lacking school-level literacy information constrained RN’s capability to intervene at the level of school education (Gomes and Sumiya Citation2021). In contrast, the identification of a basic-education solution to the problem of low literacy levels, informed by the wide range of data as mentioned previously, helped CE come up with appropriate and adaptive use of various policy instruments as illustrated below.

Table 2. Variations of policy capacity in CE and RN

Unlike RN, which has approached decentralization narrowly as giving greater autonomy to state-run schools without taking into account the municipal schools, CE exhibited strong capacity in supporting and coordinating with municipal schools underpinned by a broader understanding of this organizational instrument as a process of orderly transfer of schools to municipalities. Alongside a layered and integrated monitoring system, the government offered support on capacity development of teachers and administrators at the municipal level through in-service training on classroom practices and provision of learning materials. While acknowledging its indispensable role, the state government only provided direct training for municipalities with critically low literary levels. For the rest, it would train the municipal secretariats of education staff, who would later train teachers within their municipalities (Loureiro et al. Citation2020, p. 20). Shortly after the launch of PAIC, the government allocated CREDE, the regional units of CE, with designated budgets and staff for implementing this strategic program, which allowed it to offer technical support to municipal educational managers and headteachers (Bonamino et al. Citation2019). This is in line with the design of PAIC itself as a holistic program which not only covers pedagogical inputs, but also education management and training of local managers (Sumiya Citation2015). Apart from relying on its own strength to help local capacitybuilding, CE has actively invigorated bottom-up exchange of local good practices. Notably, it has done so through the Escola Nota 10 program which has rewarded top-performing schools that have shared their good practices with low-performing ones since 2009 (Loureiro et al. Citation2020). Lastly, CE’s high operational capacity is further exhibited through its adaptive redesign of ICMS transfer rules. Initially, indicators on literacy carried the highest weight in the index that serves as the basis of the transfer. With more progress being made in CE on this front, more weight was subsequently given to the attainment of students in higher grades (Costa and Carnoy Citation2015), so that the incentives of local actors are updated towards fulfilling upgraded policy objectives.

4.2.3. Political Capacity

Underlying both the push for consolidating a comprehensive data infrastructure and analytical apparatus and the launch of various policy instruments informed by analytical insights, the system in CE has long exhibited an unswerving political determination for education reform and improvement (). This political will largely stemmed from the performance-based legitimacy enjoyed by the state government. Many of the masterminds behind CE’s reforms were former officials from Sobral, who were elected to state-level office primarily due to their success in turning around the educational performance in that municipality (McNaught Citation2022). This contributed to their commitment to bringing state-wide improvement in basic education by tapping into their previous experience, which was a political driver behind the launch of PAIC. With earlier reform endeavors positively recognized in elections, they were less likely to be incentivized to pursue personal or clientelist gains that deviate from public value creation. The fact that the new governor was a former mayor of a “turnaround municipality” also boosted the confidence and provided inspiration to other mayors. Together with the governor’s personal effort of visiting many municipalities in the countryside to promote the PAIC, this has resulted in full municipal participation in the program as mentioned earlier that transcended party differences among the mayors. The political will of the leadership team was further demonstrated through the award ceremonies of Escola Nota 10. Regarded by teachers as the “Oscars of education”, these ceremonies were attended by key politicians and senior bureaucrats as a way to pay tribute to educators. These efforts joined and corroborated earlier endeavors by a former member of CE’s state parliament who was the key champion behind CCEAE in 2004.

Alongside political will, CE’s political capacity is further reflected in the system’s ability to draw sector-wide support for both treating education as priority and the subsequent measures taken. The maintenance of the same political leadership since 2006 revealed public trust for the government. Beyond that, such capacity is also reflected in the government’s redesign of ICMS, which was mentioned earlier as a showcase of operational capacity. Here, it is worth highlighting that not only does the ICMS represent a substantial share of the municipal budget in CE, but the municipalities were granted freedom as to how these funds are used (with no stipulation that it has to be spent on education). This design feature sent the message that improving educational outcomes will not only benefit the SEDUC-CE, but potentially all other departments, and, importantly, municipal secretariats. The state government’s vision of education reform was thus solidly put forward and effectively shared. The clear and adaptive formula on which rewards of the transfer can be calculated, and the more general move to focus on literacy improvement, a target that can be achieved in the relatively short term, also helped remove attitudinal barriers to placing education high on the political agenda that are experienced in many developing countries. Finally, CE’s long-established embrace of participation and contributions of non-state actors in the policy process provided robust venues for aligning stakeholder interests. One example in this regard was CCEAE that took place in CE’s Legislative Assembly in 2004, which facilitated both the recognition of the literacy problem at the school level and the consensus on a basic education solution to the problem.

In contrast, government leadership in RN, both in general and for the education sector, has experienced constant instability. Only one governor has been reelected since 2000, and the SEEC-RN had a reshuffle of ten secretaries during her governorship (2003–2010). This turbulence reflected weak voter confidence, which in turn impaired the continuity of education policies and the willingness of political leadership to advocate substantial reforms. Instead, it increased the chances that key official positions may serve more as an instrument of political accommodation and partisanship, as noted in RN’s Court of Account in 2014.

The lackluster political will for education reforms in RN is further reflected in the shortage of pro-reform coalition or policy entrepreneurs to push for change. A former secretary of SEEC-RN revealed that she was not able to build any momentum to propose substantial changes (Silva Citation2020). The idea of education reforms also seemed in collision with some influential stakeholders, such as the teacher’s union and a group of professors at a local university that later became secretaries of SEEC-RN. As the transfer of Fundef/Fundeb funds is according to the number of students enrolled at each subnational level, state-level actors seemed to view the municipalities as competitors in receiving funding, rather than potential collaborators with whom to work together towards a shared goal. In such a political environment, even when there were occasional initiatives by non-state actors, they were mostly ignored by the government rather than being appreciated and insights from them being deliberated and incorporated into policy. Apart from the UNICEF example mentioned earlier, RN has also received technical and financial support from the World Bank during 2015–2018. Yet likewise, no substantial change was facilitated regarding political commitment for education reforms and improvement through this partnership.

5. Discussion

Through a systematic unpacking of different types of policy capacity underlying the reform initiatives in CE and RN, our analysis shows that with a specialized and professional team, CE was able to introduce a series of reforms since the 1990s to strengthen the generation of comprehensive and relevant data. This, in turn, helped the state keep track of the system's status and progress and serves as an informational basis for subsequent reforms that launched diverse and innovative policy instruments to solve the issues identified. CE’s reforms were further sustained and strengthened by a committed political leadership that was able to cultivate system-wide interest alignment. Underpinned by high levels of analytical, operational and political capacity, education system reforms in CE were well-designed and competently implemented: individual components were logically sequenced, functionally complementary and closely integrated, the combination of which provided a solid foundation for the current high performance of CE’s education sector. In contrast, RN’s sense-making of the status and gaps of its education system was compromised by a lack of both interest and expertise on gathering and analyzing information, which in turn impaired its ability to devise effective instruments that target the root cause of the problems. Political turbulence within the state also made it difficult to foster political support and pro-reform coalitions. Therefore, despite enjoying a more abundant pool of general and education-specific resources than CE, RN was substantially constrained by a much lower level of policy capacity, making its reform experience resemble a scenario of non-design, in which “problems, goals, instruments and outcomes” of its scant and incoherent reform measures “may be defined but have no clear link with each other” (Chindarkar et al. Citation2022, p. 325).

In sum, our analysis has illustrated how the variations of analytical, operational and political capacity between CE and RN can jointly account for their varying educational outcomes. As for the potential interactions or even internal causal chain within these dimensions, the case of CE seems to suggest that strong political capacity has created favorable conditions for analytical and operational capacity to develop, while the reverse seems to have characterized the case of RN. However, can this be taken as indicating that a high level of political capacity is a necessary condition for other dimensions of capacity to develop? Lacking proper exploration of the important perspectives of policymakers leaves us unable to provide a full answer to this question, which is also beyond the scope of the article. Having said that, recent theorization of Chindarkar et al. (Citation2022, table 19.2) offers a useful starting point for further exploration, in which four possible policy design outcomes are conceptualized along the levels of analytical capacity and of operational and political capacity as two key dimensions. Our cases exemplify the scenarios of capable design (CE) and poor design (RN), whereas the case of teacher capacity-building in Delhi reported in Yan and Saguin (Citation2021) exemplifies capable political design, for which good political designs were manifested that may be technically poor. More in-depth case studies like these are thus encouraged to facilitate a more nuanced understanding of the interactions among different dimensions of policy capacity in education reforms.Footnote10

6. Conclusion

How can we make sense of the variegated student learning outcomes in two socioeconomically similar states two decades after their respective education reforms? Arguments along the lines of input cannot provide a convincing answer in our case: if anything, RN is slightly more advanced socioeconomically than CE, while both are among the poorest states even within Brazil. This article provided an alternative explanation by zooming into the policy capacity involved in designing and implementing these reforms. Our findings not only reveal the challenges arising from and beyond resource constraints, but also how a synergized combination of analytical, operational and political capacity underlying reform efforts can lead to considerable improvement of educational outcomes against the odds of less favorable socioeconomic conditions. The detailed unpacking of how an education system in the poorest region of a developing country can possess a high level of policy capacity may thus offer inspiring lessons for other education systems that find themselves under similar resource constraints. Even within Brazil, the practical significance of CE’s experience was already being recognized, as some of its reform initiatives were “transferred” up to the federal level. RN also started to receive PAIC materials from CE in 2021, and sent them to schools, but with no support on developing the capacity necessary for the recipients to make full use of them. If the termination of PNAIC, the federal equivalent of CE’s PAIC, in 2018, is anything to go by, “copying” policy interventions directly from the source site is unlikely to succeed without taking into account the sophisticated set of capacities required to make reforms work. Beyond this cautionary note, whether there exist some critical aspects of policy capacity that should be prioritized (Bali and Ramesh Citation2021), or how different types of capacity should be developed simultaneously in sync, remain critical questions to be explored in future research.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the editor and anonymous referees for their valuable comments to earlier versions of the article. A note of special thanks goes to Sonja Blum, Ellen Fobé, Valérie Pattyn, Guy Peters and other participants at PSG XXI Policy Design and Evaluation session of the European Group for Public Administration (EGPA) Annual Conference 2021, for their helpful feedback to the version presented there. The authors are also grateful to PSG XXI Policy Design and Evaluation, PSG XIII Public Policy and the Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis for shortlisting the article for the best comparative policy paper award at EGPA 2021.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yifei Yan

Yifei Yan is a Lecturer in Public Administration and Public Policy at the University of Southampton, after holding an LSE Fellowship in International Social and Public Policy at the London School of Economics and Political Science for the past three years since September 2019. Her research interests lie at the intersections of public policy and administration, social policy and educational studies, with non-Western contexts including China, India and Brazil as the main empirical focus of her research.

Hironobu Sano

Hironobu Sano is an Associate Professor of Public Management at the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil. He is a former director of the Brazilian Society for Public Administration (SBAP). His research focuses mainly on public sector innovation, policy capacity, federalism and intergovernmental coordination, and governance.

Lilia Asuca Sumiya

Lilia Asuca Sumiya is a Professor of Public Management at the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil. She is coordinator of the Brazilian Network of Studies on the Implementation of Public Educational Policies (REIPPE). Her main research interests lie in the areas of education policy design, implementation, inequality, and policy capacity.

Notes

1. SDG4 calls for “ensur[ing] inclusive and equitable quality education and promot[ing] lifelong learning opportunities for all”. See this official website https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal4 for more information.

2. Brazil is a federal republic with three autonomous government levels: federal, state and municipal. After the 1996 LDB Act, municipal governments are mostly responsible for early childhood and primary education; secondary education is shared with municipal and state governments and high school mostly by state governments. A brief overview of federal-level policies is available in in the appendix, which shows that national legislation and nationwide programs over the past few decades covered areas such as assessment, state–municipal coordination, literacy improvement etc., but with limited presence overall. This reflects the historical trend that basic education provision has long been decentralized to state and municipal levels. As such, even when certain policy moves (such as state–municipal coordination) are emphasized by federal-level documents, it is mainly the state governments that decide to what extent these will be taken on board. This autonomy gives rise to substantial state-level variations on reform experience and outcomes (Carnoy et al. Citation2017), as we will see in the contrast between CE and RN.

3. Please refer to this official website http://ideb.inep.gov.br/ for more information.

4. Source of data: https://download.inep.gov.br/educacao_basica/saeb/2018/documentos/presskit_saeb2017.pdf

5. The Portuguese acronyms for State Secretariat of Education are different in the two states. To avoid confusion, we use the original acronym together with the state being referred to (SEDUC-CE and SEEC-RN, respectively).

6. National/federal-level policies and program documents were consulted as background information. All 37 policy documents reviewed are listed in in the appendix.

7. See Beach (Citation2020) for more details on what is called the “bottom-up case-based approach”. We are grateful to our anonymous reviewer for raising this point. As the lack of explicit investigation of temporal dynamics of capacity has been identified as a common gap in the empirical literature on policy capacity across different sectors (Mukherjee et al. Citation2021), future research along this direction is also expected to make a major methodological contribution.

8. We thank our anonymous reviewer for inspiring this point.

9. The specific roles and responsibilities of these units vary from state to state. As is the case with State Secretariats, the names of these regional units are state-specific too. In CE, it goes by the acronym of CREDE; in RN, it is DIRED.

10. We thank anonymous reviewers for comments that have inspired the discussion here.

References

- Bali, A. S. and Ramesh, M., 2018, Policy capacity: A design perspective, in: M. Howlett and I. Mukherjee (Eds) Routledge Handbook of Policy Design (New York: Routledge), pp. 331–344.

- Bali, A. S. and Ramesh, M., 2019, Assessing health reform: Studying tool appropriateness & critical capacities. Policy and Society, 38(1), pp. 148–166. doi:10.1080/14494035.2019.1569328

- Bali, A. S. and Ramesh, M., 2021, Governing healthcare in India: A policy capacity perspective. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 87(2), pp. 275–293. doi:10.1177/00208523211001499

- Batley, R. and Mcloughlin, C., 2015, The politics of public services: A service characteristics approach. World Development, 74, pp. 275–285. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.05.018

- Baxter, J., 2020, Distrusting contexts and cultures and capacity for system-level improvement, in: M. Ehren and J. Baxter (Eds) Trust, Accountability and Capacity in Education System Reform, 1st ed. (Oxon: Routledge), pp. 78–101.

- Beach, D., 2020, Causal case studies for comparative policy analysis, in: B. G. Peters and G. Fontaine (Eds) Handbook of Research Methods and Applications in Comparative Policy Analysis (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), pp. 238–253.

- Bonamino, A., Mota, M. O., Ramos, M. E. N., Correa, E. V., 2019, Arranjo institucional de implementação do PAIC e burocratas de médio escalão, and G. Lotta Ed. Teoria e análises sobre implantação de políticas públicas no Brasil (Brasília: Enap), pp. 193–224.

- Brenton, S., Baekkeskov, E., and Hannah, A., 2022, Policy capacity: Evolving theory and missing links. Policy Studies. doi:10.1080/01442872.2022.2043266

- Bruns, B., Macdonald, I. H., and Schneider, B. R., 2019, The politics of quality reforms and the challenges for SDGs in education. World Development, 118, pp. 27–38. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.02.008

- Carnoy, M., Marotta, L., Louzano, P., Khavenson, T., Guimarães, F. R. F., and Carnauba, F., 2017, Intranational comparative education: What state differences in student achievement can teach us about improving education—the case of Brazil. Comparative Education Review, 61(4), pp. 726–759. doi:10.1086/693981

- Chindarkar, N., Ramesh, M., Howlett, M., 2022, Designing social policies: Design spaces and capacity challenges, in: B. G. Peters and G. Fontaine (Eds) Handbook of Research on Policy Design (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar), pp. 323–337.

- Costa, L. and Carnoy, M., 2015, The effectiveness of an early-grade literacy intervention on the cognitive achievement of Brazilian students. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 37(4), pp. 567–590. doi:10.3102/0162373715571437

- El Masri, A. and Sabzalieva, E., 2020, Dealing with disruption, rethinking recovery: Policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in higher education. Policy Design and Practice, 3(3), pp. 312–333. doi:10.1080/25741292.2020.1813359

- Gomes, M., Hirata, G., and Oliveira, J., 2020, Student composition in the PISA assessments: Evidence from Brazil. International Journal of Educational Development, 79, pp. 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2020.102299

- Gomes, S. and Sumiya, L. A. (Eds), 2021, Diagnóstico das Desigualdades Educacionais no Rio Grande do Norte (Natal: EDUFRN).

- Grindle, M., 2004, Despite the Odds: The Contentious Politics of Education Reform (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press).

- Hallak, J. and Poisson, M., 2005, Ethics and corruption in education: An overview. Journal of Education for International Development, 1(1), pp. 1–15.

- Haque, M. S., Ramesh, M., Puppim de Oliveira, J. A., and Gomide, A. D. A., 2021, Building administrative capacity for development: Limits and prospects. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 87(2), pp. 211–219. doi:10.1177/00208523211002605

- Howlett, M., Ramesh, M., and Capano, G., 2020, Policy-makers, policy-takers and policy tools: Dealing with behaviourial issues in policy design. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 22(6), pp. 487–497. doi:10.1080/13876988.2020.1774367

- Hwa, -Y.-Y., 2020, Contrasting approaches, comparable efficiency? How macro-level trust influences teacher accountability in Finland and Singapore, in: M. Ehren and J. Baxter (Eds) Trust, Accountability and Capacity in Education System Reform, 1st ed. (Oxon: Routledge), pp. 222–251.

- Loureiro, A., Cruz, L., Lautharte, I., and Evans, D. K., 2020, The State of Ceara in Brazil is a Role Model for Reducing Learning Poverty (Washington, DC: The World Bank).

- Mangla, A., 2015, Bureaucratic norms and state capacity in India: Implementing primary education in the Himalayan region. Asian Survey, 55(5), pp. 882–908. doi:10.1525/as.2015.55.5.882

- Mansoor, Z. and Williams, M., 2018, Systems Approaches to Public Service Delivery: Lessons from Health, Education, and Infrastructure. Background Paper for Workshop “Systems of Public Service Delivery in Developing Countries” (Oxford: University of Oxford).

- Masino, S. and Niño-Zarazúa, M., 2016, What works to improve the quality of student learning in developing countries? International Journal of Educational Development, 48, pp. 53–65. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2015.11.012

- McNaught, T., 2022, A problem-driven approach to education reform: The story of Sobral in Brazil. RISE Insight 2022/039. doi:10.35489/BSG-RISE-RI_2022/039

- Mukherjee, I., Bali, A. S., and Coban, K., 2021, Policy capacities and effective policy design: A review.Policy Sciences, pp. 1–26. doi:10.1017/S0007114521003524

- Peters, B. G., 2022, Can we be casual about being causal? Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 24(1), pp. 73–86. doi:10.1080/13876988.2020.1793327

- Saguin, K. I. and Ramesh, M., 2020, Bringing governance back into education reforms. The case of the Philippines. International Review of Public Policy, 2(2), pp. 159–177. doi:10.4000/irpp.1057

- Silva, A. L., 2020, Os Estados importam! Determinantes da cooperação subnacional nas políticas de educação e saúde do Brasil, Dissertation, FGV-EAESP, Brasil.

- Sumiya, L. A., 2015. A hora da alfabetização: atores, ideias e instituições na construção do PAIC-CE, Dissertation, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Brasil.

- Sumiya, L. A., Araujo, M. A., and Sano, H., 2017, A hora da alfabetização no Ceará: O PAIC e suas Múltiplas Dinâmicas. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 25(36), pp. 1–31. doi:10.14507/epaa.25.2641

- Tan, C., 2018, Comparing high-performing Education Systems: Understanding Singapore, Shanghai, and Hong Kong (London: Routledge).

- Vieira, S. L., Plank, D. N., and Vidal, E. M., 2019, Educational policy in Ceará: Strategic processes. Educação E Realidade, 44(4), pp. 1–24.

- Wu, X., Ramesh, M., and Howlett, M., 2015, Policy capacity: A conceptual framework for understanding policy competences and capabilities. Policy and Society, 34(3–4), pp. 165–171. doi:10.1016/j.polsoc.2015.09.001

- Yan, Y., 2019a, Governance of government middle schools in Beijing and Delhi: Supportive accountability, incentives and capacity, Dissertation, National University of Singapore, Singapore.

- Yan, Y., 2019b, Making accountability work in basic education: Reforms, challenges and the role of the government. Policy Design and Practice, 2(1), pp. 90–102. doi:10.1080/25741292.2019.1580131

- Yan, Y. and Saguin, K., 2021, Policy capacity matters for capacity development: Comparing teacher in-service training and career advancement in basic education systems of India and China. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 87(2), pp. 294–310. doi:10.1177/0020852320983867

Appendix

Table A1. Educational outcomes, socioeconomic indicators and resource levels in CE and RN

Table A2. Policy documents at federal and state levels of Brazil, 1988–2020

Table A3. Major reforms at the national/federal level since 1990

Table A4. Evolution of Ideb for primary government schools