Abstract

This article explores a backlash against the net zero greenhouse gas emissions target within the UK. It introduces the term “anti-net zero populism” to analyse ideological and opportunistic counter-movements working to undermine climate policy. It builds a conceptual framework based on the literatures on “policy dismantling” and “discursive opportunity structures” to analyse how right-wing populists seek to undermine the net zero goal and dismantle policies. The article compares these efforts across six specific policy areas involved in pursuing net zero. Overall, it contributes to understanding the roles of discourse for policy dismantling, and the comparative strategies pursued to undermine net zero.

1. Introduction: The Emergence and Actors of Anti-Net Zero Populism

This article analyses a process of populist backlash between 2021 and 2022 that attempted to visibly delegitimise and dismantle the overall architecture of climate change policy in the UK. This development resonates with counter-movements against climate policy in Canada, Hungary, Poland, Sweden, and the US, amongst others. It also echoes earlier periods of populist reaction against climate policy, notably the fuel protests of 2000 in the UK (Doherty et al. Citation2003). Alongside these older populist episodes, there is a longer history of opposition to climate action in the UK, although it has generally been marginal politically. These new net zero campaigns were organised principally by the “Net Zero Scrutiny Group” (NZSG) of Conservative MPs and their allies outside parliament.

We conceive of this new and ongoing campaign against net zero as “anti-net zero populism” (ANZP; cf. Atkins Citation2022, who terms this “net zero populism”). This focus on net zero and associated policy targets and instruments is more specific than the approach right-wing populists have taken to climate change policy and politics more generally (e.g. Daggett Citation2018; Lockwood Citation2018; Gunster et al. Citation2020). Indeed, in the UK, the Global Warming Policy Foundation, established in 2009 by former Chancellor of the Exchequer Nigel Lawson, has historically focused on denying climate change itself (Bychawski Citation2022). While this nascent political movement has yet to achieve its goals, its rhetoric has garnered much attention, and has been employed in a similar vein in other countries.

Where others have framed populism as a loose ideology (Mudde Citation2007; see for discussion Tosun and Debus Citation2021), here we understand it more flexibly as a “political logic” that has been increasingly incentivised by the institutional development of political systems (Jager and Piquer Citation2020; Bickerton and Innvernizi Accetti Citation2022). The cartelisation of political parties, combined with rising inequalities, incentivise political elites of varying ideological positions to mobilise populist rhetoric, invoking a noble people betrayed by a corrupt elite, to build symbolic connections between themselves and potential supporters (Jager and Piquer Citation2020; Bickerton and Innvernizi Accetti Citation2022). While our analysis shows how net zero populists mobilise performative expertise to criticise climate and energy policy, this is not surprising; technocratic arguments can complement populist rhetoric as a means of enforcing how populists understand and can deliver the will of the people (Bickerton and Innvernizi Accetti Citation2022). We explore ANZP as a form of intra-party populism (Watts and Bale Citation2019); that is, our analysis focuses on the efforts of anti-net zero populists to drive policy dismantling within the Conservative Party, rather than in electoral competition.

The primary two MPs who initiated the NZSG were Steve Baker and Craig Mackinlay, who published articles criticising net zero in the spring and summer of 2021 (Baker Citation2021a; Mackinlay Citation2021a). Momentum around ANZP intensified in October 2021, when Baker founded the NZSG, an organisation of Conservative MPs. At the time of writing (June 2023), the NZSG is small, comprising 19 Conservative MPs and one Conservative member of the House of Lords, with Craig Mackinlay and Steve Baker as its leading members (Hermann Citation2022). Within parliament, these arguments have also circulated in the All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on “Fair Fuel for UK Motorists and UK Hauliers”, chaired by Mackinlay, and focused on opposing additional costs for and restrictions on motorists (APPG Citation2021). Outside parliament, the key group is Power Not Poverty, a group campaigning for a referendum on the net zero goal.Footnote1 Finally, ANZP messages have strong support in partisan conservative media outlets, notably the Telegraph, Daily Mail, Daily Express, GB News, and several Talk Radio stations.

Backlashes against climate policy represent an ongoing issue to address in the pursuit of an effective global response to the urgent threat of climate change (Patterson Citation2022). The UK represents a useful case for analysing such reactions, because of its long-standing status as a relative climate policy leader and pioneer (Tobin Citation2017), with a well-established range of legislation against which coalitions can be generated. Although the UK has seen widespread normative support for action on climate change – it is a valence issue – the policy area has been dogged by low political salience, whereby other priorities have pushed climate change down the political agenda (Carter and Pearson Citation2022). From the early 2010s onwards, a normative commitment to climate action remained, but with growing willingness to frame climate change as positional. While it has been less the case since Rishi Sunak became prime minister, during Liz Truss’ time as PM the overall composition of the government reflected a substantial change in orientation compared to the rhetorically pro-climate Boris Johnson government. Indeed, with some qualifications, it reflected the interests and focus of NZSG members, several of whom became cabinet ministers under Truss (Harvey and Horton Citation2022; Paterson Citation2022).

We begin by outlining how we understand and deploy the concepts of policy dismantling and discursive opportunity structures. Next, we detail the methods for the research out of which our empirical analysis arises, showing how our argument is based on research to collect and analyse the rhetoric of ANZP actors in this period, as produced in speeches, letters to the press, Twitter, and other documents and sources. In our empirical analysis, we examine the operation of ANZP discourse – first towards the net zero policy target itself, and then through a comparison of the way ANZP actors have targeted specific policies within the climate policy architecture.

We analyse the efforts of ANZP actors to drive policy dismantling by showing how they strategically navigate various discursive opportunity structures for different policies. Such discursive opportunity structures refer to openings for the creation of “sensible” discourses (Koopmans and Statham Citation1999). These discourses matter: not only can they be replicated by similar movements outside the UK if shown to be effective, but they seek to lay the foundations for dismantling a complex policy architecture that is needed to achieve urgent climate targets. Drawing on the typology of policy dismantling produced by Bauer et al. (Citation2012), we argue that ANZP so far has not generated either symbolic or active dismantling by the UK government. Nonetheless, shifts in government make-up and nascent counter-movements raise the possibility of an intensified dismantling of specific elements within the existing climate policy architecture, or even the entire programme and its goals.

2. Climate Policy Dismantling and Discursive Opportunity Structures

“Policy dismantling,” understood as the “cutting, diminution or removal of existing policy” (Jordan et al. Citation2013, p. 795), has emerged as a concept to explain those processes where either specific policies, or broad policy architectures, are dismantled (Bauer et al. Citation2012). Environmental policy has been central to the development of this concept (Gravey and Jordan Citation2016; Burns et al. Citation2018; Burns and Tobin Citation2020; Pollex and Lenschow Citation2020). A central argument regards how the “valence” of environmental issues means that policymakers rarely wish to make visible their desire to dismantle environmental policy (Burns et al. Citation2018). With growing awareness of a possible backlash to climate action (Patterson Citation2022), policy dismantling has been employed to analyse climate policy in particular, especially at the European Union (EU) level (Gravey and Jordan Citation2016, Citation2020; Burns and Tobin Citation2020; Lenschow et al. Citation2020), but also at the individual country level (O’Neill and Gibbs Citation2020). Existing research suggests that there is some evidence of climate policy dismantling at national levels, and that “a surprisingly large number of individual climate policies have not been durable enough” (Jordan and Moore Citation2022, p. 2, citing van Renssen Citation2018; see also Gravey and Jordan Citation2020; O’Neill and Gibbs Citation2020). In contrast, the EU’s legislative institutions seem relatively immune to environmental policy dismantling, despite talk about such dismantling, albeit with instances of dismantling by technical committees (Gravey and Jordan Citation2020, pp. 350–352, see also Burns and Tobin Citation2020; Pollex and Lenschow Citation2020).

The “visibility” of dismantling is important to policymakers because they may fear reprisals or expect rewards for pursuing dismantling. Thus, determining the visibility of dismantling is one means for scholars to understand the motivations, or concerns, of policymakers. We use Bauer et al.’s (Citation2012) typology of policy dismantling, which includes the visibility of any dismantling as a core variable for defining forms of policy dismantling. The effectiveness of actors’ discourses when seeking to build pro-dismantling coalitions are paramount to determining how visible any subsequent dismantling will be, and indeed the likelihood of any dismantling at all. Thus, in our study we focus on two forms of dismantling outlined by Bauer et al. (Citation2012): anti-net zero campaigns towards symbolic dismantling – where ANZP forces cause the UK to abandon net zero rhetoric in name, but the actual policies remain in place – and towards active dismantling, in which both the net zero goal and specific initiatives are abandoned.

The UK case raises two nuances that complement this typology and its use. The first pertains to the relationship between the broad architecture of climate policy and the specifics of individual policies. In the UK during the 2010s, there was some dismantling by default. This is largely because, while the combination of the UK’s self-image as a climate leader and key institutional features of the 2008 Climate Change Act have ensured that overall goals of climate policy are difficult to dislodge symbolically, their normative and institutional power has only a tenuous connection to the substance of specific policies. The second nuance is the need to pay attention to the goals, interests, and power of the dismantlers, combined with the opportunity structures they face: as we show, it is this combination that explains their choice of targets for dismantling and thus which aspects of climate policy are likely to be dismantled if they are successful.

We analyse the discourses pursuing the highly visible dismantling of net zero – be it the overall goal, or the norms supporting it – by targeting the policy areas that underpin it. We see these narratives as not just reactive but strategic – discourses deployed deliberately by ANZP actors to build and mobilise public support against net zero, with a view to achieving either symbolic or active dismantling. We employ “discursive opportunity structures” (DOS, see Koopmans and Statham Citation1999; McCammon Citation2013) to examine how ANZP actors seek to shape which ideas are perceived as “sensible”, “legitimate”, or “realistic” (Koopmans and Statham Citation1999). Thus, analysis of DOS enables examination of the discourses used as strategic tools by actors wishing to dismantle net zero goals, by influencing which policies are deemed legitimate.

The net zero target has a different opportunity structure compared to the general logic of mitigation or the Johnson government’s “Green Industrial Revolution”, with the resultant potential to create distinct coalitions. Compared to the programme of emissions reductions, net zero suggests a more rapid and intense project of transformation, and a stronger confrontation with entrenched fossil fuel interests. Compared to Johnson’s “Green Industrial Revolution”, net zero is more technocratic, less connected to imaginaries of national revival and green jobs, and is more easily associated with ideas of restriction and challenges to traditional freedoms. As such, net zero represents a strategic target for attack.

3. Methods

We focus in this article on the discursive or rhetorical strategies of ANZP. As noted above, we analyse the discourses deployed by actors seeking to dismantle climate policy, rather than the process of dismantling by governments. We therefore ask, how do they argue against net zero and what do they appear to be trying to achieve via these arguments? We focus specifically on attacks on net zero because this has been the core focal point of ANZP.

Our analysis is based on a collection of documentary and media evidence regarding the activities of the NZSG and its allies. We undertook data collection and analysis in two stages. First, we used Factiva to collect all articles in the mainstream print media written about the NZSG and its allies. The time period for this data is between May 2021 and June 2022, meaning we are not in a position to evaluate their rhetoric beyond that period, notably when Liz Truss became PM or after that. Article searches were carried out with the terms “climate change” and “net zero” to capture media entries. The data were analysed manually to identify key narratives deployed both at the level of general attacks on the goal of net zero, and the specific policies they targeted in their campaigns. Through this analysis we traced the central actors involved in the backlash to net zero, their interests and goals, the arguments they use, and the core net zero policies they focus on. As such, we have not sought evidence regarding the motivations of ANZP actors, and so can make only indirect inferences from observing the patterns and forms of discourse they have produced. We are more interested in the variations in these discourses and what they tell us about the potential for ANZP to undermine UK climate policy than about the “real” objectives of ANZP actors.

Second, the core policy areas ANZP focused upon laid the basis for a second exploratory data collection process. We inductively identified policy areas to undertake an exploratory analysis of the discursive strategies of actors (Seawright and Gerring Citation2008). “Cases”, in this context, are the specific targets of attack by ANZP actors. We determined that these targets operate at two (albeit interrelated) levels: some articles focused on the overall goal of and rationale for net zero, while others targeted specific policy areas that are framed as part of the net zero policy package. The six most targeted policies were: the fracking moratorium, heat pumps, renewables, electric vehicles, petrol and diesel bans, and low traffic neighbourhoods (LTNs). Articles were selected with headlines specifying critical angles on the policies. This range gave us a basis for a comparison of cases with significant variation in terms of overall narratives, discursive opportunity structures, and involvement of different specific actors, specifically national net zero populists, grassroots campaigners, and the right-wing press. Such discourses were then cross-referenced with direct ANZP interventions in the media and on Twitter to understand how they related to these broader media discourses.

4. Attacks on the Goal of Net Zero

One discursive line of attack has been directly on the goal of net zero itself. The attack on net zero mobilised an interesting combination of populist discourses signifying a betrayal of the people by the elite, as well as performances of alternative technical expertise. These frame elites as imposing the costs of climate action on the “people”. ANZP actors have exploited the technocratic nature of climate policymaking in the UK to leverage arguments about elitism. Nonetheless, they also mobilise alternative forms of counter-expertise to build narratives around the potentially catastrophic impacts of net zero, including the fiscal burden, economic costs, and impacts on the quality of life it would entail. These rhetorical strategies articulate clearly with a set of political and economic interests benefiting from anti-net zero rhetoric, connected both to the promotion of fossil fuel interests and to a vision to restructure the UK around libertarian economic principles.

Counter-expertise has been leveraged in a distinct way from the older politics of climate opposition focused on denying the scientific validity of anthropogenic climate change. The GWPF established “Net Zero Watch” in October 2021 and moved towards publishing “research” and opinion pieces documenting the technical failings of net zero and climate policy, and their potential social and economic consequences. Its core aims were to “scrutinise policies, establish what they really cost, determine who will have to pay, and explore affordable alternatives” (Net Zero Watch Citation2022). Only Nigel Lawson (Citation2021), GWPF founder, made a climate denial argument in any of the articles we found.Footnote2 Steve Baker shared a piece of climate denial by the GWPF but in comments suggested that “questions of climate science should be handled scientifically” (Horton Citation2022b). The side-lining of climate denial represents a strategic move, given its low salience in UK climate politics, as well as a broader shift from “denial to delay” in anti-climate movements (Lamb et al. Citation2020). It has enabled ANZP actors to frame themselves as concerned allies rather than ideologically opposed enemies of Conservative climate governance. Connections between ANZP and organisations tied to climate denial suggest that some may be sympathetic to this argument.

Instead, ANZP actors have focused on mobilising discourse that combines specific technical critiques of climate policies with broader critiques of the political legitimacy of climate governance. Within this particular form of techno-populism critiques of climate policy are used to anticipate future social and economic impacts that will lead to a revolt from the betrayed people. In May 2021, Steve Baker (Citation2021a) argued that “[u]nless someone invents a way to store energy in massive bulk, Net Zero will mean quivering under duvets in the dark on windless winter nights. We are on the path to poverty, misery and a failure to inspire the world to decarbonise”. This claim about feasibility is then allied to one about costs and their distributive qualities: “We have almost uniquely caused our energy prices, through taxation and environmental levies, to increase faster than those of any other competitive country. High energy prices … are felt most painfully by the lowest paid” (Telegraph Citation2022). Baker later predicted that, once these true and suppressed costs are discovered, there will be a widespread political backlash, stating that “we could end up with something bigger than the poll tax, certainly bigger than Brexit, because the numbers of people hit by it and their inability to cope will be huge” (Steve Baker as quoted in Thomas-Peter Citation2021).

Integral to these substantive attacks on net zero as a goal is an attack on the institutional form of climate policy, framing the Climate Change Committee (CCC) as an incompetent, elitist organisation with too much power within UK climate policy. Craig Mackinlay argued that “we … know that government advisors didn’t trust the CCC numbers”, and that based on BEIS’ own analysis, “instead of costing £50 billion a year in 2050, the cost of Net Zero was likely to be £70 billion a year. This is 40 per cent higher than the CCC figure. In total, it amounts to £1.3 trillion” (Mackinlay Citation2021b). These attacks on the institutional legitimacy of the CCC then were used to reinforce the substantive claims about the costs of net zero, and the credibility of the prime minister, who accepted the CCC’s assessments uncritically. Mackinlay (Citation2021b) called doubt on the honesty and intentions of Boris Johnson’s climate policymaking, arguing that his claim that the cost of renewables had fallen by 70 per cent in a decade was false, and that subsidies to offshore wind have increased substantially since their introduction in 2002.

Other parts of the coalition have focused on more straightforward populist discourses and tactics, imported from the Brexit campaign. A key tactic was thus to campaign for a referendum, just as with Brexit. From October 2021 to March 2022, Net Zero Watch and Power Not Poverty, drawing clearly on the established repertoire of the Brexit campaign, initiated a campaign for a referendum on the UK’s net zero target, arguing that a public debate and referendum are the only way to determine the legitimacy of the net zero target by 2050 (Owen Citation2022). The Vote Power Not Poverty website hammers home the parallels with the Brexit campaign, with a central slogan on the home page that we must “take back control” of our energy policies, and stating their intent to mobilise “the might and will of the British people” to challenge “a Net Zero agenda that will destroy British jobs, while making us poorer and colder” (Power Not Poverty Citation2022). Following a YouGov Poll in October 2021, Net Zero Watch claimed that 42 per cent wanted a referendum, 30 per cent opposed it, and 28 per cent didn’t know (Net Zero Watch Citation2021). Partly because it was not supported by the NZSG or the right-wing press, this campaign was not successful, fizzling out after the group had to cancel a rally at Bolton Wanderers Football Club on 26 March 2022, with Power Not Poverty claiming that “[o]ur current venue has also now become a target of intimidation” (Power Not Poverty Citation2022).

In addition to the Brexit repertoire for populist campaigners, their arguments reflect various other discursive opportunity structures available to ANZP actors. One is the lack of salience of climate denial. Another is the shift to net zero as the overall goal of UK government climate policy. Net zero is a somewhat vague and flexible policy target that requires considerable explication, and is readily detached from the broadly supported focus on climate change action amongst the UK population. Its discursive hollowness creates a robust space for other actors to mobilise performative counter-expertise to construct alternative narratives. Targets such as the petrol and diesel ban, and heat pump promotion that are integral to net zero were therefore envisioned by ANZP actors as technically deficient but also as driving new inequalities and forms of social injustice. Here the discursive performance of expertise therefore expresses both an awareness of the technical challenges of transition with a sensitivity to the needs of a population confronting rising social inequalities and worsening government trust. The experience of the Brexit campaign gave ANZP actors significant experience of effectively deploying these storylines around economic inequalities and cultural threats, but here they also appear to have incorporated elements of the Remain campaign framed by Brexiters as “project fear”.

5. Comparing Attacks on Individual Net Zero Policy Areas

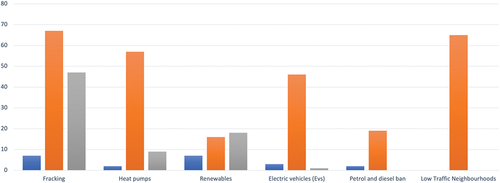

Alongside attacking general aspects of the net zero policy programme, actors have also made claims on the ground of expertise to critique particular policy targets. Here they have balanced divergent discursive opportunity structures available for specific targets with a broader set of coalitional interests, producing a wide range of interventions. summarises these types of public intervention via media and social media.

Figure 1. Targets of attack, May 2021 to June 2022

Three patterns merit noting from . First, the fracking moratorium dominates the overall story. This overall pattern has also been marked by a temporal shift in focus, with fracking becoming more important over time, and renewables less so (Ellicott Citation2022). The NZSG’s first public letter, released in January 2022, argued that the fracking moratorium, combined with green levies, was driving the rise in energy prices in the UK (Telegraph Citation2022). In their final public letter, they shifted their focus solely to the fracking moratorium, excluding commentary on green levies. While renewables have been a second focus of ANZP, the right-wing press has not matched this attention. Second, while low traffic neighbourhoods gain much media attention in general in articles critical of net zero, core backlash actors have ignored it as a target of attack. Third, electric vehicles, the petrol car ban, and heat pumps have received little attention as a target of attack from ANZP. Below we analyse these patterns by linking them to two distinct dismantling strategies related to two broader sets of discursive opportunity structures.

illustrates and compares the different types of rhetoric, with key examples, for each target. The overall pattern across our categories is instructive. The variation can be understood through a combination of the discursive opportunity structures the ANZP actors encounter, and their strategic objectives and interests.

Table 1. Comparing rhetoric for different targets

In one sense, this focus on fracking appears surprising. There are stronger underlying discursive opportunities for opposing heat pumps, electric vehicles, and the petrol and diesel ban, where there are genuine concerns about the equitability of these policies. Fracking lacks public support and there are few sets of economic or cultural grievances to mobilise against fracking. Nonetheless, the focus on fracking is unsurprising in the context of literature which concerns how fossil fuel interests shape political struggles over climate change policy (Newell and Paterson Citation1998; Hochstetler Citation2020; Mildenberger Citation2020; Stokes Citation2020). It is important to note we did not find direct links between ANZP actors and fossil fuel interests: they do not sit on oil and gas corporate boards or lobby groups directly for such interests. However, alignments between Net Zero Watch and the Global Warming Policy Foundation suggest an important connection.

This alignment with the interests of dominant energy corporations also helps to explain the absence of green hydrogen, which is broadly favoured by the gas industry as a climate “solution”. Land grabbing and offsets are also not mentioned. While these would be vulnerable to populist critiques, they are also aligned with corporate interests the ANZP actors could be cautious to confront. In contrast, it is notable that heat pumps, the petrol and diesel ban, and electric vehicles also represent threats to fossil fuel interests, albeit more diffusely. This allegiance explains ANZP actors’ neglect of LTNs, which could be ripe for populist critique but are not as immediately threatening to fossil fuel interests in the same way as the other targets.

Nonetheless, we contend that it is not sufficient to understand divergences in focus on policy targets simply in terms of the interests underlying their activity. To understand their targets and the likelihood of their efficacy it is vital to understand how ANZP actors work to navigate different discursive opportunity structures. Newer policy targets such as heat pumps and the petrol and diesel ban present more blatant discursive opportunities for particular critiques as well as a broader critique of the net zero target. Here actors mobilised more forceful affective claims about the costs of these policy targets, aiming to stoke fear and concern about them and net zero. On the surface, they represent a basis for advancing a genuine populist backlash against net zero, linking policy critique to the broader agenda of dismantling climate policy.

However, there are also complications to the incentives and opportunities in relation to these policy targets. Firstly, these policies are future targets and generally have not led to widespread socio-technical change thus far. In this context, critiques risk appearing somewhat breathless. Secondly, they lack robust incentives to focus on these, given that it is unclear yet that they represent serious threats to coalitional interests. Finally, our actors remain broadly disconnected from genuine popular movements. For example, it is notable that they generally neglected low traffic neighbourhoods despite the fact that these, alongside 15-minute cities, have subsequently become a clear focus area for alt-right mobilisations.Footnote3

In contrast, conjunctural discursive opportunity structures created more robust space to critique the fracking moratorium and other energy policies, helping to explain the gravitation of our ANZP actors to these targets. Despite the unpopularity of fracking amongst the British public, the energy and cost of living crises exacerbated by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, as well as robust press support, created a reasonable basis for actors to challenge the fracking moratorium (see Atkins Citation2022). Chancellor Rishi Sunak signalled a depoliticising acceptance of spiking energy prices (Elliott and Inman Citation2022), creating an opening for actors to link the fracking moratorium to higher energy prices, suggesting this as a betrayal of the people framed in terms of the “national interest”. By linking rising energy prices to the fracking moratorium and green levies, they aimed to depoliticise efforts to weaken support for renewables and bring back fracking, framing it as undeniably within the national interest (Feindt et al. Citation2021).

Technical claims about the cost and inadequacy of renewables were used to build support for this fracking programme. While the Conservative press were willing to show support for the critique against fracking, this argument did not garner broader public appeal or exert much leverage in the Conservative Party. Instead, that press has given positive coverage to renewables as creating new industrial investment, boosting jobs and economic growth, as well as enhancing energy security. It is notable that while the Net Zero Scrutiny Group’s initial letter also suggested a link between green levies and rising energy prices, they later backed off this claim, perhaps in line with a lack of broader media support in opposition to renewables. Notably, the focus on fracking suggests a tension within their campaign. Despite elements of populist rhetoric, our analysis indicates that incentives and opportunities to represent unpopular fossil fuel interests were treated as more important than the underlying issues of equitability in broader climate policies.

Crucially, the ANZP actors have been most successful with these technical elements of their strategy. Rather than mobilise the people in favour of fracking, they successfully instigated a review of fracking in the UK as part of a broader energy security review. In April 2022, the government commissioned a new review by the British Geological Survey into the risks involved in fracking (HM GOV Citation2022). At the Conservative Party conference in September 2022, Net Zero Watch hosted a panel entitled “Unlocking the potential of shale gas in the UK”. Only ten people attended, according to Desmog (Barnett Citation2022). Truss lifted the fracking ban in September 2022, but Rishi Sunak put it back in place swiftly after assuming office in October (Elgot and Horton Citation2022). Ultimately, there are not strong signs that they will be successful in mobilising government support to end the fracking moratorium.

6. Conclusions

In this article, we have analysed how ANZP actors deploy both populist and technical rhetoric in efforts to dismantle climate policy, and the challenges they have faced in doing so. We have shown how particular discursive opportunity structures available to them have shaped the way they combine technical and political critiques of climate policy, and how this has been channelled in efforts to both politicise elements of net zero policy and depoliticise suggestions for energy policy, particularly in terms of ending the fracking moratorium. This is suggestive, not only for the analyses of specific outcomes of struggles to promote or oppose climate action, but also for theoretical debates about the concept of policy dismantling. It shows that by paying attention to the opportunity structures available to actors seeking to dismantle policy, we can generate specific explanations of their choices of targets for dismantling, of their likely chances of success in dismantling efforts, and at least strong hypotheses about their underlying motivations for seeking to dismantle policy in a given area. We have not sought to demonstrate in any systematic way these motivations, but the inferences we can make from the discourse analysis are useful to guide subsequent research.

The assault on the net zero goal has largely failed to dismantle this basic aim of UK climate policy, at least so far. Within government, the campaign against net zero led to a technocratic exercise during Liz Truss’ time as PM, as she appointed Chris Skidmore (a Conservative MP vocally in favour of net zero) to lead a review into the policy (Horton Citation2022a). Whether this was designed to undermine Skidmore’s ability to criticise the government under Truss as it sought to dismantle the pursuit of net zero is unclear. In any case, the Skidmore review (Skidmore Citation2023) was published months after Truss had left office, and produced a resolute and emphatic defence of net zero as a goal and as a broad economic opportunity. Furthermore, the composition of the government under Sunak eliminated a number (but not all) of the highly visible opponents of net zero that had been in Truss’ government. Outside parliament, however, the idea of a net zero referendum is not dead. Indeed, on 26 November 2022, the Telegraph announced “growing” support for a net zero referendum, citing a new number: 44 per cent of Britons now support a referendum on net zero (Hazell Citation2022). And more recent protests against the “15-minute city” (e.g. O’Sullivan and Zuidijk Citation2023) signal that the articulation by ANZP actors (not the NZSG itself, but others, like Nigel Farage, see Southbank Investment Research Citation2023) with the LTN issue is growing.

The analysis has implications for the pursuit of net zero and climate change action more generally. The rise of backlash to climate policy in the UK provides important evidence that institutional mechanisms to stabilise climate policy are not sufficient to lock in transitions. Political coalitions remain vital to the stability or instability of climate policy. Our analysis of their rhetorical activity also showed that climate policy would benefit from engaging with economic and cultural grievances, through either policy designs or consultation processes, to reduce risks of deep public and political backlashes. This is particularly the case in relation to an ongoing cost of living crisis, which, while driven by the rise in natural gas prices and corporate profiteering that started in 2021 and was intensified by the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, is nevertheless routinely associated by ANZP actors, and more broadly in media discourse, as driven by net zero and the promotion of “green energy”.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participants in a workshop at the University of Manchester in July 2022 for stimulating discussions that led to this article. We would also like to thank Mitya Pearson and James Patterson for comments on an earlier draft of this article. We are grateful to the Sustainable Consumption Institute and the Tyndall Centre at Manchester for funding the underlying research. The support of the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) is gratefully acknowledged, having funded Paul Tobin via grant ES/S014500/1 during his involvement in this article. For the purpose of open access, the authors have applied for a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Matthew Paterson

Matthew Paterson is Professor of International Politics and Director of the Sustainable Consumption Institute. His research focuses on the political economy, global governance, and cultural politics of climate change.

Stanley Wilshire

Stanley Wilshire is a PhD student in politics at the University of Manchester and a member of the Sustainable Consumption Institute. He researches the politics of climate change and the political economy of sustainable energy transitions.

Paul Tobin

Paul Tobin is a Senior Lecturer in Politics at the University of Manchester, UK, where he specialises in environmental politics, European politics, and public policy.

Notes

1. This group involved Nigel Farage, Richard Tice (Chair of the Reform Party, previously Brexit Party and UKIP), Graham Stringer (APPG member and “maverick” Labour MP), among others.

2. There are other groups within the UK parliament that still do use climate denial rhetoric, such as members of the Bruges Group. But they have played little role in the current backlash. We are grateful to John O’Neill for pointing this out. Our analysis is based on the public discourses of the NZSG; we do not have evidence whether climate denial is present in their internal conversations.

3. As a historical counter-example, Nigel Farage has previously promoted critique of road closures and cycle lanes (Donnelly Citation2020) but did not focus on that during our period of data collection.

References

- APPG fair fuel for UK motorists and hauliers, 2021, APPG 2030 Ban, August. Available at https://fairfueluk.com/APPG-FFUK/2/

- Atkins, E., 2022, ‘Bigger than Brexit’: Exploring right-wing populism and net-zero policies in the United Kingdom. Energy Research & Social Science, 90, p. 102681. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2022.102681.

- Baker, S., 2021a, It’s alright for some. The Critic Magazine, 21 May. Available at https://thecritic.co.uk/its-alright-for-some/

- Baker, S., 2021b, The “Net zero” boiler ban will leave Britain’s poorest out in the cold. The Sun, 25 May. Available at https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/15068214/net-zero-boiler-ban-britains-poorest-cold/

- Baker, S., 2022, “The estimated Bowland gas … ” [Tweet]. Twitter. Available at https://twitter.com/SteveBakerHW/status/1501236539162075139

- Barnett, A., 2022, Old school climate science denial lingers on outskirts of Tory conference. Desmog. Available at https://www.desmog.com/2022/10/04/old-school-climate-science-denial-lingers-on-outskirts-of-tory-conference/

- Bauer, M. W., Jordan, A., Green-Pedersen, C., and Héritier, A., 2012, Dismantling Public Policy: Preferences, Strategies, and Effects (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

- Bickerton, C. and Innvernizi Accetti, C., 2022, Technopopulism: The New Logic of Democratic Politics (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

- Bradley, T., 2022a, Only well-off can afford EVs say drivers. The Express, 15 January. https://www.express.co.uk/life-style/cars/1550537/EV-petrol-cars-electric-vehicles-well-off-never-buy

- Bradley, T., 2022b, UK will have less than a quarter of required EV chargers by 2030. The Express, 20 April. https://www.express.co.uk/life-style/cars/1598180/uk-ev-chargers-petrol-diesel-2030-ban

- Burns, C. and Tobin, P., 2020, Crisis, climate change and comitology: Policy dismantling via the backdoor? JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 58(3), pp. 527–544. doi:10.1111/jcms.12996.

- Burns, C., Tobin, P., and Sewerin, S. (Eds), 2018, The Impact of the Economic Crisis on European Environmental Policy (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

- Bychawski, A., 2022, Exclusive: Influential UK-net zero sceptics funded by US oil ‘dark money.’ Open Democracy. Available at https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/dark-money-investigations/global-warming-policy-foundation-net-zero-watch-koch-brothers/

- Carter, N. and Pearson, M., 2022, From green crap to net zero: Conservative climate policy 2015–2022. British Politics. doi:10.1057/s41293-022-00222-x.

- Chillingworth, L., 2022, Petrol and diesel ban is an attack ‘on the working class’ –‘Only the rich will have cars’. Daily Express. Available at https://www.express.co.uk/life-style/cars/1551244/petrol-diesel-car-ban-electric-vehicle-ownership

- Daggett, C., 2018, Petro-masculinity: Fossil fuels and authoritarian desire. Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 47(1), pp. 25–44. doi:10.1177/0305829818775817.

- Doherty, B., Paterson, M., Plows, A., and Wall, D., 2003, Explaining the fuel protests. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 5(1), pp. 1–23. doi:10.1111/1467-856X.00093.

- Donnelly, D., 2020, Nigel Farage declares war on Boris Johnson over green revolution- ‘Madness!’ Daily Express. Available at https://www.express.co.uk/news/politics/1368923/Nigel-Farage-news-reform-party-green-roads-transport-boris-Johnson-ont

- Elgot, J. and Horton, H., 2022, Rishi Sunak will keep ban on fracking in UK, No 10 confirms. The Guardian. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/oct/26/rishi-sunak-ban-on-fracking-uk-no-10

- Ellicott, C., 2022, Top Tories call on Boris Johnson to ditch plans to ban fracking with launch of ‘national mission’ to end Britain’s reliance on foreign gas. Daily Mail. Available at https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-10584451/Top-Tories-call-Boris-Johnson-ditch-plans-ban-fracking.html

- Elliott, L. and Inman, P., 2022, Rishi Sunak tells Britons to brace for even higher energy costs in autumn. The Guardian. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/business/2022/feb/03/rishi-sunak-tells-britons-to-brace-for-even-higher-energy-costs-in-autumn

- Feindt, P. H., Schwindenhammer, S., and Tosun, J., 2021, Politicization, depoliticization and policy change: A comparative theoretical perspective on agri-food policy. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 23(5–6), pp. 509–525.

- Gravey, V. and Jordan, A., 2016, Does the European Union have a reverse gear? Policy dismantling in a hyperconsensual polity. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(8), pp. 1180–1198. doi:10.1080/13501763.2016.1186208.

- Gravey, V. and Jordan, A. J., 2020, Policy dismantling at EU level: Reaching the limits of ‘an ever-closer ecological union’? Public Administration, 98(2), pp. 349–362. doi:10.1111/padm.12605.

- Gunster, S., Neubauer, R., Bermingham, J., and Massie, A., 2020, Our oil”: Extractive populism in Canadian social media, in: W. K. Carroll (Ed.) Regime of Obstruction: How Corporate Power Blocks Energy Democracy (Edmonton: Athabasca University Press), pp. 197–224.

- Harvey, F. and Horton, H., 2022, Will Liz Truss’s government adopt or weaken green policies? The Guardian, 7 September. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/sep/07/will-liz-trusss-government-adopt-or-weaken-green-policies

- Hazell, H., 2022, Desire for net zero referendum growing among public, poll finds. The Telegraph. Available at https://www.telegraph.co.uk/politics/2022/11/26/desire-net-zero-referendum-growing-among-public-poll-finds/

- Hermann, M., 2022, Net zero scrutiny group. DeSmog. Available at https://www.desmog.com/net-zero-scrutiny-group/ (accessed 6 January 2023).

- HM GOV, 2022, Review of the geological science of shale gas fracturing. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/review-of-the-geological-science-of-shale-gas-fracturing

- Hochstetler, K., 2020, Political Economies of Energy Transition: Wind and Solar Power in Brazil and South Africa (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

- Horton, H., 2022a, Liz Truss appoints green Tory Chris Skidmore to lead net zero review. The Guardian. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2022/sep/08/liz-truss-appoints-green-tory-chris-skidmore-to-lead-net-zero-review

- Horton, H., 2022b, Tory MP Steve Baker shares paper denying climate crisis. The Guardian. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2022/apr/15/tory-mp-steve-baker-shares-paper-denying-climate-crisis

- Jager, A. and Piquer, J., 2020, After the cartel party: “Extra-party” and “Intra-party” techno-populism. Politics and Governance, 8(4), pp. 533–544. doi:10.17645/pag.v8i4.3444.

- Jordan, A., Bauer, M. W., and Green-Pedersen, C., 2013, Policy dismantling. Journal of European Public Policy, 20(5), pp. 795–805. doi:10.1080/13501763.2013.771092.

- Jordan, A. J. and Moore, B., 2022, The durability–flexibility dialectic: The evolution of decarbonisation policies in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(3), pp. 425–444. doi:10.1080/13501763.2022.2042721.

- Koopmans, R. and Statham, P., 1999, Ethnic and civic conceptions of nationhood and the differential success of the extreme right in Germany and Italy, in: M. Giugni, D. McAdam, and C. Tilly (Eds) How Social Movements Matter (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press), pp. 225–251.

- Lamb, W. F., Mattioli, G., Levi, S., Roberts, J. T., Capstick, S., Creutzig, F., Minx, J. C., Müller-Hansen, F., Culhane, T., and Steinberger, J. K., 2020, Discourses of climate delay. Global Sustainability, 3, pp. e17, 1–5. doi:10.1017/sus.2020.13.

- Lawson, N., 2021, Net zero is a disastrous solution to a nonexistent problem. The Spectator. Available at https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/net-zero-is-a-disastrous-solution-to-a-nonexistent-problem (accessed 15 September 2022).

- Lenschow, A., Burns, C., and Zito, A., 2020, Dismantling, disintegration or continuing stealthy integration in European Union environmental policy? Public Administration, 98(2), pp. 340–348. doi:10.1111/padm.12661.

- Littlewood, M., 2021, We were fracking idiots to ignore the energy on our doorstep. The Telegraph, 24 September. Available at https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2021/09/24/fracking-idiots-ignore-energy-doorstep/

- Lockwood, M., 2018, Right-wing populism and the climate change agenda: Exploring the linkages. Environmental Politics, 27(4), pp. 712–732. doi:10.1080/09644016.2018.1458411.

- Mackinlay, C., 2021a, The Government is fooling itself if it thinks it can go down the net zero path without electoral damage. 16 July. Available at https://www.conservativehome.com/platform/2021/07/craig-mackinlay-the-government-is-fooling-itself-if-it-thinks-it-can-go-down-the-net-zero-path-without-electoral-damage.html

- Mackinlay, C., 2021b, What will net zero cost? The Critic Magazine, 17 August. Available at https://thecritic.co.uk/issues/august-september-2021/what-will-net-zero-cost/

- Malnick, E., 2022, Tory grandees urge Boris Johnson to lift ‘unconservative’ ban on fracking. The Telegraph, 12 February. Available at https://www.telegraph.co.uk/politics/2022/02/12/tory-grandees-urge-boris-johnson-lift-unconservative-ban-fracking/

- McCammon, H., 2013, Discursive opportunity structure, in: The Wiley‐Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements. doi:10.1002/9780470674871.wbespm073.

- Mildenberger, M., 2020, Carbon Captured: How Business and Labor Control Climate Politics (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press).

- Mudde, C., 2007, Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

- Net Zero Watch, 2021, 42% of British adults want referendum on net zero. Available at https://www.netzerowatch.com/42-of-british-adults-want-referendum-on-net-zero/

- Net Zero Watch, 2022, Who we are. Available at https://www.netzerowatch.com/who-we-are/

- Newell, P. and Paterson, M., 1998, A climate for business: Global warming, the state and capital. Review of International Political Economy, 5(4), pp. 679–703. doi:10.1080/096922998347426.

- Norman, M., 2022, Do you think LTN’s are a good thing? Oxford Mail, Available at https://www.oxfordmail.co.uk/news/20158812.oxfordshires-ltns-may-increasing-pollution-nearby-roads/ (accessed 7 October 2022).

- NZSG, 2022, Letters: It’s time to overhaul the testing regime and get Britain moving again, 2 January. The Telegraph. Available at https://www.telegraph.co.uk/opinion/2022/01/02/letters-time-overhaul-testing-regime-get-britain-moving/

- O’Neill, K. and Gibbs, D., 2020, Sustainability transitions and policy dismantling: Zero carbon housing in the UK. Geoforum, 108, pp. 119–129. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.11.011.

- O’Sullivan, F. and Zuidijk, D., 2023, The 15-minute city freakout is a case study in conspiracy paranoia. Bloomberg.Com, 2 March. Available at https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-03-02/how-did-the-15-minute-city-get-tangled-up-in-a-far-right-conspiracy

- Owen, G., 2022, Nigel Farage’s new drive for vote to kill off Boris’s ‘ruinous’ green agenda: He got us out of the EU … Now the former UKIP chief demands a referendum on net zero. Daily Mail. Available at https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-10581529/amp/Nigel-Farage-campaign-Net-Zero-policy-referendum.html

- Paterson, M., 2022, What Liz Truss’s government means for climate action. The Conversation. Available at http://theconversation.com/what-liz-trusss-government-means-for-climate-action-190280 (accessed 7 October 2022).

- Patterson, J. J., 2022, Backlash to climate policy. Global Environmental Politics, 23(1), pp. 68–90. doi:10.1162/glep_a_00684.

- Pollex, J. and Lenschow, A., 2020, Many faces of dismantling: Hiding policy change in non-legislative acts in EU environmental policy. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(1), pp. 20–40. doi:10.1080/13501763.2019.1574869.

- Power Not Poverty, 2022, Vote power not poverty. Available at https://votepowernotpoverty.uk/

- Prosser, E. J., 2022, Cost of low traffic neighbourhoods is ‘Deeply troubling,’ say critics. Oxford Mail. Available at https://www.oxfordmail.co.uk/news/19858298.oxford-locals-react-cost-ltn-scheme/ (accessed 7 October 2022).

- Reeves, F., 2022, “This is dictatorship”: Drivers savage 2030 petrol and diesel car ban. The Express. Available at https://www.express.co.uk/life-style/cars/1597234/petrol-diesel-car-ban-2030-electric-vehicles-angry-drivers-reaction

- Seawright, J. and Gerring, J., 2008, Case selection techniques in case study research: A menu of qualitative and quantitative options. Political Research Quarterly, 61(2), pp. 294–308. doi:10.1177/1065912907313077.

- Skidmore, C., 2023, Mission Zero: Independent review of net zero. Department for Energy Security and Net Zero. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/review-of-net-zero (accessed 25 May 2023).

- Smith, M., 2022, While opposition has dropped, Britons remain against fracking for shale gas, YouGov. Available at https://yougov.co.uk/topics/politics/articles-reports/2022/09/22/while-opposition-has-dropped-britons-remain-agains (accessed 7 October 2022).

- Southbank Investment Research, 2023, Nigel Farage: 15-minute cities are about control, not convenience. 3 March. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YtlwrF8calQ

- Stokes, L. C., 2020, Short Circuiting Policy: Interest Groups and the Battle over Clean Energy and Climate Policy in the American States (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

- The Sun, 2021, We should have got cracking with fracking to keep Britain heated and powered. The Sun. Available at https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/16194518/cracking-with-fracking-keep-britain-powered/

- The Telegraph, 2022, It’s time to overhaul the testing regime and get Britain moving again. The Telegraph. Available at https://www.telegraph.co.uk/opinion/2022/01/02/letters-time-overhaul-testing-regime-get-britain-moving/

- Thomas-Peter, H., 2021, Net zero targets could cause more unrest and division than Brexit, Tory MP warns. Sky News. Available at https://news.sky.com/story/net-zero-targets-could-cause-more-unrest-and-division-than-brexit-tory-mp-warns-12520837 (accessed 10 June 2022).

- Tice, R., 2022a, “Energy crisis: Heat pumps are wasteful … ” [Tweet]. Twitter. Available at https://twitter.com/TiceRichard/status/1496128408899788805

- Tice, R., 2022b, “Concerned British citizens …,” [Tweet]. Twitter, 28 March. Available at https://twitter.com/TiceRichard/status/1508465194116292613

- Tobin, P., 2017, Leaders and laggards: Climate policy ambition in developed states. Global Environmental Politics, 17(4), pp. 28–47. https://doi.org/10.1162/GLEP_a_00433

- Tosun, J. and Debus, M., 2021, Right-wing populist parties and environmental politics: Insights from the Austrian Freedom Party’s support for the glyphosate ban. Environmental Politics, 30(1–2), pp. 224–244. doi:10.1080/09644016.2020.1813997.

- van Renssen, S., 2018, The inconvenient truth of failed climate policies. Nature Climate Change, 8(5), pp. Article 5. doi:10.1038/s41558-018-0155-4.

- Wallop, H., 2022, How “low-traffic neighbourhoods” have added to congestion on our roads. Mail Online, 1 April. Available at https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-10674487/HARRY-WALLOP-low-traffic-neighbourhoods-added-congestion-roads.html

- Watts, J. and Bale, T., 2019, Populism as an intra-party phenomenon: The British labour party under Jeremy Corbyn. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 21(1), pp. 99–115. doi:10.1177/1369148118806115.