Abstract

Context: Herbal therapies are used worldwide to treat health conditions. In Mexico, generations have used them to treat gingivitis, periodontitis, mouth infections, and discoloured teeth. However, few studies have collected scientific evidence on their effects.

Objective: This study aimed at searching and compiling scientific evidence of alternative oral and dental treatments using medicinal herbs from Mexico.

Methods: We collected various Mexican medicinal plants used in the dental treatment from the database of the Institute of Biology at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. To correlate with existing scientific evidence, we used the PubMed database with the key term ‘(scientific name) and (oral or dental)’.

Results: Mexico has various medical herbs with antibacterial and antimicrobial properties, according to ancestral medicinal books and healers. Despite a paucity of experimental research demonstrating the antibacterial, antimicrobial, and antiplaque effects of these Mexican plants, they could still be useful as an alternative treatment of several periodontal diseases or as anticariogenic agents. However, the number of studies supporting their uses and effects remains insufficient.

Discussion and conclusion: It is important for the health of consumers to scientifically demonstrate the real effects of natural medicine, as well as clarify and establish their possible therapeutic applications. Through this bibliographical revision, we found papers that testify or refute their ancestral uses, and conclude that the use of plants to treat oral conditions or to add to the dental pharmacological arsenal should be based on experimental studies verifying their suitability for dental treatments.

Introduction

Humans have sought cures for diseases in nature since ancient times; even recently, the use of herbal medicines in dietary supplements, energy drinks, multivitamins, massage, and weight loss products has gained popularity (Petrovska Citation2012). These uses have broadened the field of herbal medicine and also increased its credibility.

The field of dentistry also has begun to exploit herbal properties for the purpose of relieving tooth pain, gum inflammation, and canker sores (Kumar et al. Citation2013). However, it is of utmost importance to understand the interactions of plant extracts with the body and other medications, as many of these extracts have anti-inflammatory effects and prevent bleeding, which is important in dental treatment (Taheri et al. Citation2011). Antiseptics, antibacterial, antimicrobial, antifungal, antioxidant, antiviral, and analgesic agents derived from plants are of widespread interest in dentistry (Sinha and Sinha Citation2014). For example, in recent years, in the field of periodontics and endodontics, several plant extracts such as a propolis, noni fruit, burdock root, and neem leaf have been used as intra-canal medications with excellent results, opening up a novel function for herbal agents in global dental therapy (Pujar and Makandar Citation2011; Shah et al. Citation2015).

In Mexico, the Aztec and Mayan cultures developed many uses for medicinal plants (Galarza Citation1981); this development ceased after the conquest, when the Spaniards controlled and evangelized the Aztecs (Cortez et al. Citation2004). The Spaniards introduced new products from the Old World to Mexico and, combined with native methods, thus enriched the natural medicine arsenal (Garcia Citation1991). Historical knowledge is essential because, without it, we would lack clarity and our medical practices would lack coherence (Estrada Citation1996). The effectiveness and possible application of numerous Mexican medicinal plants has not yet been studied with respect to dentistry. Dental services even in the urban and in the rural areas of Mexico are expensive, and it is difficult for people to access the appropriate drugs (Medina-Solis et al. Citation2006; Maupome et al. Citation2013). For these reasons, herbal remedies in Mexico are commonly used despite the lack of scientific support for their use, dosage, and effects (Andrade-Cetto Citation2009). In fact, people use them without caution because they believe such alternative treatments have no risks or no possibility of allergic reactions or other adverse effects as they come from natural sources. Therefore, it is important to study, analyse, and test the efficacy of traditional medicinal plants to establish and promote their use as alternative treatments or as potential sources for obtaining or developing new drugs.

This study describes and clarifies the types of alternative oral and dental treatments based on herbal therapies that are commonly used in Mexico. We also reviewed the limited experimental evidence regarding herbal therapy to support the use of traditional Mexican medicine as a possible aid in the treatment of dental and oral pathologies, as well as a potential source for the development of drugs.

Literature search

We collected the various Mexican medicinal plants used in dental treatment from the database of the Institute of Biology at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (Digital Library of Traditional Mexican Medicine; DLTMM). We searched the electronic literature in the PubMed database with the keyword ‘(scientific name) and (oral or dental)’ to correlate with existing scientific evidence on the Mexican plants.

Uses of herbal medicines in ancient Mexican cultures

The rise of Mexican medicine occurred during the Aztec and Maya empires and all or almost all of information on these ancestral medicinal skills was collected in codices by religious orders, such as the Franciscans (Galarza Citation1981; Garcia Citation1991). Aztec medicine had a magical-religious approach to healing or the treatment of disease (Estrada Citation1985). Using the same approach, the medicinal skills of Mayans included methods to heal wounds and counter rattlesnake venom, massage techniques to restore dislocations or banish inflammation, hot baths involving herbal steam cooking, and the use of pricks from porcupine spines to treat neuralgia, similar to the principle of Chinese acupuncture (Berdaguer Citation1991; Cañigera et al. Citation2003; Santana et al. Citation2015). With regard to oral or dental treatments, the Mayans used quartz powder as an abrasive to clean out carious cavities before sealing them with a powder mixture that had a high resistance to mastication (De la Cruz Citation1975). For the treatment of the dental pain, they used the root of Chicalote (Argemone Mexicana L. [Papaveraceae]) as a reliable anaesthetic (Galarza Citation1981; Estrada Citation1996; Cortez et al. Citation2004).

The Florentine Codex, which was written in Náhuatl, the native language, and translated into Spanish by Fray Bernardino de Sahagún in 1557, describes the names and uses of many medicinal plants and animal materials (Galarza Citation1981; Terraciano Citation2010). The Libelus de medicinabilus indorum herbis was written by Martín de la Cruz, an indigenous Mexican doctor, and translated by Juan Badiano from Náhuatl into Latin. It contains descriptions of herbs’ effects and their applications along with colour illustrations, covering all diseases of the human body by beginning with the head and ending with the signs of death. It includes a section on oral health and dental conditions, and ultimately paints a holistic view of stomatology (De la Cruz Citation1975; Garcia Citation1991; Estrada Citation1996; Salas and Rivas Citation2001). In 1712, the Anthology Medicinal also described many Mexican herbal dental treatments (Rojas Citation2009).

Despite the fact that Mexico is rich in medicinal plants, this area of medicine has not been completely developed, or at least, is not a priority in Mexican medicine (Lautie et al. Citation2008). Herbal culture is transmitted orally from generation to generation (De la Rosa Citation1980). Herbal products are preferred over prescription medications for treating certain illnesses because of their lower cost or because people may believe the herbs to be less toxic, given that they are natural (Rivera et al. Citation2005a; Brindis et al. Citation2013). Generally, people visit the doctor only if they do not respond to home remedies (Waldstein Citation2008). In rural communities, traditional medicine is the best choice for the people, even if the community has medical services (Arrieta-Baez et al. Citation2012). A study of the use of complementary and alternative medicine among Hispanics found that the most commonly reported alternative therapies were herbs, prayer, and dietary supplements (Mikhail et al. Citation2004). Mexican street markets offer plants that are used as analgesics, anti-inflammatory treatments, and antiseptics, as well as treatments for pathologies as varied as scorpion stings and cancer (Josabad Alonso-Castro et al. Citation2012). Medicinal plants are used for a wide variety of purposes and are traded both nationally and internationally (Moreno et al. Citation2006).

Traditional uses of Mexican herbs in dentistry

In Mexico, the most common oral diseases are caries and periodontal disease. However, dental services in rural areas are very expensive and do not represent a primary health concern for rural people, who prefer to use alternative medicine for this common but simple oral disease. Approximately 59.6% of people in Mexico have signs of periodontal disease and the prevalence of caries in the population over age 40 is close to 97% (Cruz and Picazzo Citation2017). The method of preparation of medicinal plants varies depending on the kind of plant, as well as the portions used (stems, leaves, and roots), route of administration (local, topical, and rinse), and time of ingestion. In some areas, people who have dental pain prepare fillings from a plant or chew the bark of multiple trees to treat inflammation, as well as use plant extracts as mouthwashes or teas.

The use of medicinal plants can be an advantage in dental practice, for example eugenol is a part of our therapeutic arsenal (Rojas Citation2009; Da Silva et al. Citation2012). Some herbal products have recently undergone a thorough investigation with regards to their potential for preventing oral diseases, such as dental caries (Moreno et al. Citation2006). Although many years had elapsed without research on medicinal plants, this trend reversed when the National Medical Institute was established in 1888, creating new possibilities for herbal remedies (Rojas Citation2009; De Micheli-Serra and Izaguirre-Avila Citation2014). Because plants are often the sources for novel drugs, their screening should be a priority in drug development (Lautie et al. Citation2008).

Medicinal plants are an important element of indigenous medical system in Mexico (Heinrich Citation2000). However, interest in their effects and subsequent demonstrative studies are lacking. presents a summary of the plants in DLTMM that are either used in Mexico or are of Mexican origin and used elsewhere for oral disease.

Table 1. Mexican plants used in the treatment of the oral disease from the Digital Library of Traditional Mexican Medicine.

Dentistry is seeking novel and effective alternative healing techniques. One possible approach is to review historical data and evaluate how people of the past cured oral disease. Through such review and analysis, new horizons in dentistry and other fields of medicine may be reached.

Experimental evidence related to the use of Mexican herbs in dentistry

Although Mexico has a great diversity of medicinal plants, research to confirm or refute their popular uses has been very limited. However, due to the popularity of these plants in different countries, we have developed great interest in learning more about Mexican medicine. presents a summary of the plants that are used in Mexico for oral disease with experimental evidence.

Table 2. Mexican plants used in the treatment of the oral disease according to experimental evidence.

Mexican Sanguinaria (Polygonum aviculare L. [Polygonaceae]), which was shown to be an anti-inflammatory, astringent, and diuretic plant, is commonly used in the treatment of gingivitis to decrease the inflammatory process (Gonzalez Begne et al. Citation2001). A clinical study in students between the ages of 18–25 years who used the Mexican Sanguinaria extract as oral rinse for 14 days found that the extract significantly decreased gingivitis from day 0 to 14 (p ≤ 0.05) (Gonzalez et al. Citation1999). A recent study demonstrated the wound healing effects of quercitrin hydrate, caffeic acid, and rutin as its active compounds (Seo et al. Citation2016). In 2000, the use of a paste manufactured from Uncaria tomentosa Willd. ex Schult. [Rubiaceae]) was compared with that of zinc oxide and eugenol for direct pulp capping (Lahoud et al. Citation2000). The results showed that the U. tomentosa paste was more efficacious, as it not only decreased pulp inflammation more effectively, but also promoted better dental reformation and was more effective against microorganisms that usually inhabit the human oral cavity; U. tomentosa inhibited 8% of Enterobacteriaceae isolates, 52% of Streptococcus mutans, and 96% of Staphylococcus aureus (Ccahuana-Vasquez et al. Citation2007). However, the tested concentrations did not have an inhibitory effect on pseudomonas aeruginosa and Candida albicans (Valerio and Gonzales Citation2005; Ccahuana-Vasquez et al. Citation2007).

In other studies, the effect of an Aloe (Aloe vera (L.) Burm.f. [Asphodelaceae]) mouthwash was investigated, as the plant has anti-inflammatory and antibacterial activities. These activities may be derived from those of aloin and emodin as active components (Surjushe et al. Citation2008). The antimicrobial susceptibility test showed that both the gel and the leaf inhibited the growth of S. aureus at 18.0 and 4.0 mm, respectively. Only the gel inhibited the growth of Trichophyton mentagraphytes (20.0 mm), while the leaf possesses inhibitory effects on both P. aeruginosa and C. albicans (Agarry et al. Citation2005). It proved its effectiveness in the treatment of gingival inflammation and led to reduced plaque (Chandrahas et al. Citation2012; Ajmera et al. Citation2013; Karim et al. Citation2014; Rezaei et al. Citation2016; Vangipuram et al. Citation2016).

In addition, researchers used a rat model to show that Wildemalva (Pelargonium zonale (L.) L'Hér. ex Aiton [Geraniaceae]), a plant known as ‘marriage or boyfriend’ (Price and Palmer Citation1993), has local haemostatic action to apply dental surgery, with the bleeding time 50% shorter in the leaf juice treatment group (18.10 ± 2.03 min) and 80% shorter in the crushed-leaf group (7.10 ± 0.88 min) than in the control group (37.6 ± 3.04 min) (Paez and Hernandez Citation2003). Meanwhile, Salgado et al. (Citation2006) demonstrated that the antibacterial and anti-inflammatory effects of the grains and flowers of Granada (Punica granatum L. [Punicaceae]) were not efficient in gingivitis. The results did not show a statistically significant difference between the control and experimental groups for both visible plaque index and gingival bleeding index.

In the states of Hidalgo, Puebla, and Tlaxcala in Mexico, the ‘evergreen’ plant (Bryophyllum pinnatum (Lam.) Kurz. [Crassulaceae]), which has green leaves throughout the year, is used for toothache, tooth whitening, and the treatment of periodontitis (Kamboj and Saluja Citation2009). In a study in rats, the inhibition of the carrageenan oedema by evergreen extract at a dose of 100 mg/kg was 80%, which was improved by increasing the dose to 200 mg/kg (Dominguez and Bacallao Citation2002). The nopal cactus (Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Miller [Cactaceae]) is also listed as one of the major components of Mexican herbology. This grows extensively throughout Mexico and is especially abundant in the arid and semi-arid regions of central Mexico (Chávez-Moreno et al. Citation2009). It is used for both its nutritive and hypoglycaemic properties. Several bioactive compounds such as indicaxanthin and betanin may contribute to various biological activities due to their potent anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory actions (El-Mostafa et al. Citation2014). In a study in rats, it reduced postprandial blood glucose by 46.0% and 23.6%, respectively (p < 0.05), in comparison to the control (Nunez-Lopez et al. Citation2013). Its anti-inflammatory effect is used in dentistry for gingivitis, ulcers, and periodontitis (Allegra et al. Citation2014). In a clinical study, sialagogues therapeutics with the infusion of nopal cactus in Mexican patients was successful in combating hyposalivation and mouth pain due to viral aetiologies (Castillo and Aldape Citation2006). In the state of Morelos, the abrojo rojo (Tribulus terrestris L. [Zygophyllaceae]), a plant with plate-like flowers with five yellow petals and spiny fruits, is used three times per day as an infusion rinse to combat gingivitis (Gauthaman et al. Citation2002). Arnica (Heterotheca inuloides Cass. [Compositae]), a plant native to the hot and temperate regions of central Mexico, is commonly used as an anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and healing agent, for the treatment of contusions, skin wounds, and bruises (Martinez Citation1984, Citation1992). In cases of gingivitis, it is used as an infusion three times per day; the results have shown 96.6% effectiveness of an arnica ethanol extract, in comparison with the 66.7% effectiveness of piroxicam (Beauballet et al. Citation2002). In San Luis Potosi, Morelos, Puebla, and Durango, is used as an anti-inflammatory treatment, for gastrointestinal disorders (e.g., diarrhoea), oral pathologies (e.g., sore throat, sore gums), and inflammations of the breast (e.g., sore nipples), as well as for urinary tract disorders and painful rectal conditions (e.g., haemorrhoids) (Sanchez-Miranda et al. Citation2013). The root of the plant is also used for the treatment of stomach and bowel cancer and inflammatory conditions (Achenbach et al. Citation1987). The active compound of this plant is kramecyne, a potent inhibitor of iNOS, COX-2, NO, TNF-α, and IL-6 production in LPS-macrophages (Martinez Citation1992). In Oaxaca, Tabasco, and Aguascalientes, oak bark (Quercus robur L. [Fagaceae]) is used as an anti-inflammatory gingival treatment, powerful astringent for throat and mouth infections, treatment for bleeding gums, and cure for acute diarrhoea (Ernst & Lehner Citation2003). Many people in Mexico also use cuachalalate (Amphipterygium adstringens Schltdl. [Anacardiaceae]) to harden their gums, but it should be noted that excessive doses of this substance can be highly toxic (Waizel and Martinez Citation2011). Care is needed because it can irritate mucous membranes, however, experimental findings in rats suggest that cuachalalate methanol extract at doses lower than 100 mg/kg protects the gastric mucosa from the damage induced by diclofenac sodium without altering either the anti-inflammatory activity or the pharmacokinetics of diclofenac sodium in comparison to omeprazole, the positive control, with a strong laxative effect (Navarrete et al. Citation2005). In Yucatán, the papauce or anona blanca (Annona diversifolia Saff. [Annonaceae]) is used as food, but its leaves are employed as an anticonvulsant, analgesic, and anti-inflammatory agent (Estrada Citation1994). Its ethanol extract caused a 25% recovery of limb function in rats and produced a similar anti-nociceptive response (ED50 = 15.35 mg/kg) to that of the reference drug tramadol (ED50 = 12.42 mg/kg) (Carballo et al. Citation2010). Castilleja tenuiflora Benth. (Orobanchaceae) is a plant used not only for snakebites or cough, but also in the treatment of inflamed ovaries. C. tenuiflora was tested in a topical model of inflammation (2-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate-induced ear oedema in mice) and found to produce a significant 20% inhibition. In contrast, indomethacin, the positive control, showed 40% inhibition (Carrillo-Ocampo et al. Citation2013).

Van Wyk et al. (Citation1995) conducted a study on the effects of Capsicum frutescens L. (Solanaceae) on the growth of oral fibroblasts ultimately expanding the use of traditional medicine in periodontology, a field in which the use of natural agents has been very limited thus far. It is traditionally used in the treatment of toothache, gum inflammation, and dental infections by ancient Mexicans. These dental effects seem to be based on a recent research showing the antibacterial and antioxidant effects of various volatile compounds such as hexadecanoic acid (Gurnani et al. Citation2016). The avocado (Persea americana Miller. [Lauraceae]) is one of the most widely recognized Mexican medicinal plants. Rosas-Piñon et al. (Citation2012) demonstrated the ability of avocado to inhibit the growth of the principal pathogens of periodontal disease. It also exerted inhibitory effects on the increased interlukin-1β in periodontal ligaments (Andriamanalijaona et al. Citation2006). Taken together, avocado could have a potential role in the prevention of oral diseases. In contrast, Vieira et al. (Citation2014) exposed Chenopodium ambrosioides L. (Dysphaniaceae) as an ineffective antimicrobial agent against S. mutans, one of the main pathogens of the mouth. Thus, their use in the treatment of toothache is unsubstantiated. This finding illustrates that even information or ‘knowledge’ that has been transmitted generationally, needs to be evaluated and confirmed.

Even more surprising are the investigations carried out by different authors in different countries on the anti-microbial effect of cacao bean (Theobroma cacao L. [Sterculiaceae]), the plant from which chocolate is derived. It has been found to be a potential substitute for chlorhexidine as a mouth rinse, with powerful anticariogenic, antibacterial, and antiplaque activities (Ooshima et al. Citation2000; Matsumoto et al. Citation2004; Srikanth et al. Citation2008; Venkatesh Babu et al. Citation2011). It would be especially useful in paediatric dentistry because it would be acceptable to children without hypersensitivity and coloration of the teeth and tongue that chlorhexidine can have on children (Al-Tannir and Goodman Citation1994). Moreover, it has been shown that its bioactive compounds such as catechins and theobromine possess strong anti-oxidant activity (Lee et al. Citation2003; Ramiro-Puig and Castell Citation2009). Thus, T. cacao is a natural source of an agent with anticariogenic and potent antimicrobial activity that has potential in the field of dentistry.

Discussion

It is well known that Mexico has a great diversity of medicinal plants (Taddei-Bringas et al. Citation1999). However, their uses are generally restricted to the treatment of simple diseases. In addition, only a few papers with appropriate experimental methods have been conducted on their effects. Although they lack supporting research, Mexican herbal therapies are effective; unfortunately, they do not receive validation from the medical sector, because of little or no interest. Some even believe that herbal medicine denigrates their profession.

Herbal therapy can offer many possible advantages. Some plants have been shown to be more effective than drugs at repairing the overall body due to the synergy of their active ingredients to have preventive effects, stimulate the regulatory action of the defensive functions of the body, and prepare for possible activity against external agents (Arteche Citation1992; Villar Citation2001). Side effects are often minor and therapeutic effects are more long lasting because of better tolerance and versatility (Comerford Citation1996). Unlike drugs that are prescribed for a specific condition, the herbal therapy may act on different targets simultaneously or acts a co-treatment with conventional medications (Cecchini Citation1978). The latter of course must be done carefully when combining agents without a medical indication (Fores Citation1997).

Herbal medicines do have some disadvantages. Depending on the type of plant, the component used, or the dose, they can be toxic. Some plants can cause abortions, interact with drugs used during surgery to prolong anaesthesia time, change vital signs, and increase postsurgical bleeding (Rivera et al. Citation2005a, Citation2005b; Albuquerque et al. Citation2011). Easy access to this type of medicine in Mexico is also a huge disadvantage because patients can consume medicinal plants without medical indication or supervision by an herbal therapeutic expert, leading to undesired medical interactions.

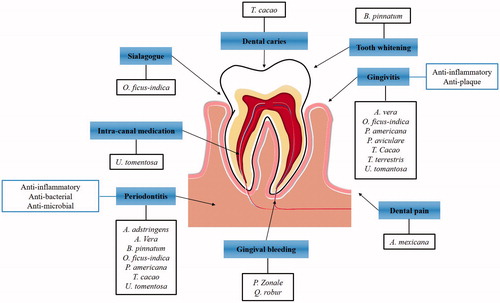

Recently, some doctors and researchers have developed an interest in discovering or confirming the therapeutic effects of Mexican medicine. For example, Arrieta-Baez et al. (Citation2012) tested the effects of traditional Mexican medicine on gastrointestinal disorders, a major disease category in Mexico, with good results for the treatment of salmonellosis. With regards to dentistry, the use of medicinal plants as anti-inflammatory, antiseptic, or antibacterial agents has led to the development of new toothpastes and new therapeutic agents (). Further studies are needed to support and continue this pioneering work, as it is vital for the effectiveness of these plants to be confirmed by research.

Figure 1. Summary of the plants that are traditionally used in Mexico or are of Mexican origin to treatment of diverse oral disease. The anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial and anti-bacterial effects of the plants are used to treatment of gingivitis, periodontitis and intra-canal medication. The anticariogenic, sialagogue and tooth whitening effect are not demonstrated yet, however, the Mexicans still used for dental treatment.

Conclusions and perspectives

It is essential to adopt a scientific attitude toward herbal medicine: critical and skeptical, but open to new knowledge. Further research should be conducted to evaluate their effectiveness as possible pharmaceutical sources and/or support their use as treatments. At the same time, care must be taken when promoting herbal medicines because, along with their therapeutic potential, there is a risk for misuse or adulteration. Above all, it is important that effects of herbal medicine can be maximized on the basis of precise plant origin and quality control. To prevent the misuse of Mexican herbal medicine, further studies are needed to establish these conditions by each herb.

Herbal medicine is not a fad; rather, it reflects a wide and varied range of therapeutic resources, including homeopathy, acupuncture, and various forms of psychotherapy, as well as therapeutic agents derived from plants. Plants have been proposed as an alternative treatment for buco-dental diseases, a domain in which long-term reliability is an important aspect of treatment. New medical professionals must be able to assimilate popular knowledge, update it, and place it in the arsenal of modern medicine for the general benefit of society.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Achenbach H, Grob J, Dominguez XA, Cano G, Star JV, Del Carmen Brussolo L, Muñoz G, Salgado F, López L. 1987. Lignans neolignans and norneolignans from Krameria cystisoides. Phytochemistry. 26:1159–1166.

- Agarry O, Olaleye M, Bello C. 2005. Comparative antimicrobial activities of Aloe vera gel and leaf. Afr J Biotechnol. 4:1413–1414.

- Ajmera N, Chatterjee A, Goyal V. 2013. Aloe vera: It's effect on gingivitis. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 17:435–438.

- Al-Tannir MA, Goodman HS. 1994. A review of chlorhexidine and its use in special populations. Spec Care Dentist. 14:116–122.

- Albuquerque RF, Evencio-Neto J, Freitas SH, Doria RG, Saurini NO, Colodel EM, Riet-Correa F, Mendonca FS. 2011. Abortion in goats after experimental administration of Stryphnodendron fissuratum (Mimosoideae). Toxicon. 58:602–605.

- Allegra M, Ianaro A, Tersigni M, Panza E, Tesoriere L, Livrea MA. 2014. Indicaxanthin from cactus pear fruit exerts anti-inflammatory effects in carrageenin-induced rat pleurisy. J Nutr. 144:185–192.

- Andrade-Cetto A. 2009. Ethnobotanical study of the medicinal plants from Tlanchinol, Hidalgo, México. J Ethnopharmacol. 122:163–171.

- Andriamanalijaona R, Benateau H, Barre PE, Boumediene K, Labbe D, Compere JF, Pujol JP. 2006. Effect of interleukin-1beta on transforming growth factor-beta and bone morphogenetic protein-2 expression in human periodontal ligament and alveolar bone cells in culture: modulation by avocado and soybean unsaponifiables. J Periodontol. 77:1156–1166.

- Arrieta-Baez D, Ruiz de Esparza R, Jimenez-Estrada M. 2012. Mexican plants used in the salmonellosis treatment. In: Kumar Y, editors. Salmonella a diversified superbug. Rijeka, Croatia: InTech.

- Arteche S. 1992. Phytotherapy. Vademecum of prescriptions.: Bilbao, Spanish.

- Beauballet F, Sainz V, Morales J, Molina M. 2002. Uses of homeopathic arnica as anti-inflammatory in traumatic facial edema. Rev Cub Med Milit. 31:177–181.

- Berdaguer R. 1991. The natural medicine. Editorial Posada S.a de C.v. Mexico. Spanish.

- Brindis F, Gonzalez-Trujano ME, Gonzalez-Andrade M, Aguirre-Hernandez E, Villalobos-Molina R. 2013. Aqueous extract of Annona macroprophyllata: a potential α-glucosidase inhibitor. Biomed Res Int. 2013:591313.

- Cañigera S, Dellacasa T, Blandoni A. 2003. Medicinal plants and phytotherapy: indicators of dependence or developmental factors? Lat Am J Pharm 22:265–278.

- Carballo AI, Martinez AL, Gonzalez-Trujano ME, Pellicer F, Ventura-Martinez R, Diaz-Reval MI, Lopez-Munoz FJ. 2010. Antinociceptive activity of Annona diversifolia Saff. leaf extracts and palmitone as a bioactive compound. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 95:6–12.

- Carrillo-Ocampo D, Bazaldua-Gomez S, Bonilla-Barbosa JR, Aburto-Amar R, Rodriguez-Lopez V. 2013. Anti-inflammatory activity of iridoids and verbascoside isolated from Castilleja tenuiflora. Molecules. 18:12109–12118.

- Castillo F, Aldape B. 2006. Factors associated with painful mouth syndrome in a population of Mexican women and their relationship with the climacteric. Av Odontoestomatol. 22:177–185.

- Ccahuana-Vasquez RA, Santos SS, Koga-Ito CY, Jorge AO. 2007. Antimicrobial activity of Uncaria tomentosa against oral human pathogens. Braz Oral Res. 21:46–50.

- Cecchini T. 1978. Encyclopedia of herbs and medicinal plants.: Barcelona. Ed de Vecchi.

- Chávez-Moreno CK, Tecante A, Casas A. 2009. The Opuntia (Cactaceae) and Dactylopius (Hemiptera: Dactylopiidae) in Mexico: a historical perspective of use, interaction and distribution. Biodivers Conserv. 18:3337.

- Chandrahas B, Jayakumar A, Naveen A, Butchibabu K, Reddy PK, Muralikrishna T. 2012. A randomized, double-blind clinical study to assess the antiplaque and antigingivitis efficacy of Aloe vera mouth rinse. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 16:543–548.

- Comerford SC. 1996. Medicinal plants of two Mayan Healers from San Andres, Peten, Guatemala. Econ Bot. 50:327–336.

- Cortez G, Macedo-Ceja J, Hernández-Arroyo M, Arteaga-Aureoles G, Espinosa-Galván D, Rodríguez-Landa J. 2004. Pharmacognosy: brief history of its origins and their relation with the medical sciences. Rev Biomed. 15:123–136.

- Cruz G, Picazzo E. 2017. The paradigm of oral health in Mexico. J Oral Res. 6:8–9.

- Da Silva NB, Alexandria AK, De Lima AL, Claudino LV, De Oliveira Carneiro TF, Da Costa AC, Valenca AM, Cavalcanti AL. 2012. In vitro antimicrobial activity of mouth washes and herbal products against dental biofilm-forming bacteria. Contemp Clin Dent. 3:302–305.

- De la Cruz M. 1975. Libellus de medicinalibus indorum herbis. Nahuatl texts medicine. Mexico City, Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

- De la Rosa F. 1980. Herbs and medicinal plants in Mexico. Mexico city, Mexico: Libro Mex-Editores.

- De Micheli-Serra AA, Izaguirre-Avila R. 2014. On New Spain and Mexican medicinal botany in cardiology. Rev Invest Clin. 66:194–199.

- Dominguez S, Bacallao M. 2002. Anti-inflammatory activity of fluid extract of leaves of evergreen (Bryophyllum pinnatum). Rev Cubana Invest Biomed. 21:86–90.

- El-Mostafa K, El Kharrassi Y, Badreddine A, Andreoletti P, Vamecq J, El Kebbaj MS, Latruffe N, Lizard G, Nasser B, Cherkaoui-Malki M. 2014. Nopal cactus (Opuntia ficus-indica) as a source of bioactive compounds for nutrition, health and disease. Molecules. 19:14879–14901.

- Ernst E, Lehner J. 2003. Folklore and Symbolism of Flowers, Plants and Trees. New York: EUA Dover publications.

- Estrada C. 1994. Caracterización de la Ilama (Annona diversifolia Saff.) en Salitre Palmerillos, Mpio. de Amatepec. Edo. De Mexico. Tesis Profesional, Departamento de Fitotecnia-UACh Chapingo. Mexico.

- Estrada L. 1996. Florentino Codex: ethnobotanics information in Mexican medicinal plants. Mexico City, Mexico UACh, p. 185–198.

- Estrada V. 1985. Botanic garden of Medicinal plants. Mexico City, Mexico UACh Spanish.

- Fores R. 1997. Atlas of healing plants and medicines: health through the plants. Madrid, Spain: Cultural SA.

- Galarza J. 1981. Mexican Codices of the National Library of Paris. Archivo General de la Nacion INAH Seminarios de códices. Mexico City, Mexico. French and Spanish: 3-130.

- Garcia R. 1991. Mexican medicinal plants, description and uses. Mexico City, Mexico Ed. Spanish.

- Gauthaman K, Adaikan PG, Prasad RN. 2002. Aphrodisiac properties of Tribulus Terrestris extract (Protodioscin) in normal and castrated rats. Life Sci. 71:1385–1396.

- Gonzalez Begne M, Yslas N, Reyes E, Quiroz V, Santana J, Jimenez G. 2001. Clinical effect of a Mexican sanguinaria extract (Polygonum aviculare L.) on gingivitis. J Ethnopharmacol. 74:45–51.

- Gonzalez M, Quiroz V, Reyes E, Banderas J, Yslas N. 1999. Mexican Sanguinaria (Polygonum aviculare L.) Applications and benefits. Universidad Autonoma del Estado de Mexico, Mexico. Ciencia Ergo Sum. 6:118–123.

- Gurnani N, Gupta M, Mehta D, Mehta BK. 2016. Chemical composition, total phenolic and flavonoid contents, and in vitro antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of crude extracts from red chilli seeds (Capsicum frutescens L.). J Taibah Univ for Sci. 10:462–470.

- Heinrich M. 2000. Ethnobotany and its role in drug development. Phytother Res. 14:479–488.

- Josabad Alonso-Castro A, Jose Maldonado-Miranda J, Zarate-Martinez A, Jacobo-Salcedo Mdel R, Fernandez-Galicia C, Alejandro Figueroa-Zuniga L, Abel Rios-Reyes N, Angel de Leon-Rubio M, Andres Medellin-Castillo N, Reyes-Munguia A, et al. 2012. Medicinal plants used in the Huasteca Potosina, Mexico. J Ethnopharmacol. 143:292–298.

- Kamboj A, Saluja A. 2009. Bryophyllum pinnatum (Lam.) Kurz.: Phytochemical and pharmacological profile. A Review. Pharmacogn Rev. 3:364–374.

- Karim B, Bhaskar DJ, Agali C, Gupta D, Gupta RK, Jain A, Kanwar A. 2014. Effect of Aloe vera mouthwash on periodontal health: triple blind randomized control trial. Oral Health Dent Manag. 13:14–19.

- Kumar G, Jalaluddin M, Rout P, Mohanty R, Dileep CL. 2013. Emerging trends of herbal care in dentistry. J Clin Diagn Res. 7:1827–1829.

- Lahoud S, Llizarbe E, Ballona C. 2000. Estudio clínico-radiográfico comparativo del recubrimiento pulpar indirecto con pasta a base de Uncaria tomentosa vs. Hidróxido de calcio y cemento óxido de zinc - eugenol. Odontol Sanmarquina. 1:9–20.

- Lautie E, Quintero R, Fliniaux MA, Villarreal ML. 2008. Selection methodology with scoring system: application to Mexican plants producing podophyllotoxin related lignans. J Ethnopharmacol. 120:402–412.

- Lee KW, Kim YJ, Lee HJ, Lee CY. 2003. Cocoa has more phenolic phytochemicals and a higher antioxidant capacity than teas and red wine. J Agric Food Chem. 51:7292–7295.

- Martinez M. 1984. Catalog vulgar amd scientific names of Mexican plants. Mexico City, Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

- Martinez M. 1992. Medicinal plants of Mexico. Mexico City, Mexico: Botas.

- Matsumoto M, Tsuji M, Okuda J, Sasaki H, Nakano K, Osawa K, Shimura S, Ooshima T. 2004. Inhibitory effects of cacao bean husk extract on plaque formation in vitro and in vivo. Eur J Oral Sci. 112:249–252.

- Maupome G, Martinez-Mier EA, Holt A, Medina-Solis CE, Mantilla-Rodriguez A, Carlton B. 2013. The association between geographical factors and dental caries in a rural area in Mexico. Cad Saude Publica. 29:1407–1414.

- Medina-Solis CE, Maupome G, Avila-Burgos L, Hijar-Medina M, Segovia-Villanueva A, Perez-Nunez R. 2006. Factors influencing the use of dental health services by preschool children in Mexico. Pediatr Dent. 28:285–292.

- Mikhail N, Wali S, Ziment I. 2004. Use of alternative medicine among Hispanics. J Altern Complement Med. 10:851–859.

- Moreno D, Flores R, Cruz M, Peña F. 2006. Medicinal plants of four markets of the state of Puebla, Mexico. Bol Soc Bot México. 79:79–87.

- Navarrete A, Oliva I, Sanchez-Mendoza ME, Arrieta J, Cruz-Antonio L, Castaneda-Hernandez G. 2005. Gastroprotection and effect of the simultaneous administration of Cuachalalate (Amphipterygium adstringens) on the pharmacokinetics and anti-inflammatory activity of diclofenac in rats. J Pharm Pharmacol. 57:1629–1636.

- Nunez-Lopez MA, Paredes-Lopez O, Reynoso-Camacho R. 2013. Functional and hypoglycemic properties of nopal cladodes (O. ficus-indica) at different maturity stages using in vitro and in vivo tests. J Agric Food Chem. 61:10981–10986.

- Ooshima T, Osaka Y, Sasaki H, Osawa K, Yasuda H, Matsumura M, Sobue S, Matsumoto M. 2000. Caries inhibitory activity of cacao bean husk extract in in-vitro and animal experiments. Arch Oral Biol. 45:639–645.

- Paez X, Hernandez L. 2003. Topical hemostatic effect of a common ornamental plant, the Geraniaceae Pelargonium zonale. J Clin Pharmacol. 43:291–295.

- Petrovska BB. 2012. Historical review of medicinal plants' usage. Pharmacogn Rev. 6:1–5.

- Price RA, Palmer JD. 1993. Phylogenetic relationships of the Geraniaceae and Geraniales from rbcL sequence comparisons. Ann Missouri Bot Gard. 80:661–671.

- Pujar M, Makandar SD. 2011. Herbal usage in endodontics- a review. Int J Contem Dent. 2:34–37.

- Ramiro-Puig E, Castell M. 2009. Cocoa: antioxidant and immunomodulator. Br J Nutr. 101:931–940.

- Rezaei S, Rezaei K, Mahboubi M, Jarahzadeh MH, Momeni E, Bagherinasab M, Targhi MG, Memarzadeh MR. 2016. Comparison the efficacy of herbal mouthwash with chlorhexidine on gingival index of intubated patients in Intensive Care Unit. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 20:404–408.

- Rivera JO, Chaudhuri K, Gonzalez-Stuart A, Tyroch A, Chaudhuri S. 2005a. Herbal product use by hispanic surgical patients. Am Surg. 71:71–76.

- Rivera JO, Gonzalez-Stuart A, Ortiz M, Rodriguez JC, Anaya JP, Meza A. 2005b. Herbal product use in non-HIV and HIV-positive Hispanic patients. J Natl Med Assoc. 97:1686–1691.

- Rojas M. 2009. Treaty of Mexican traditional medicine. Historical basis, clinical and theory-therapeutic practice. Mexico City, Mexico: Tlahui Edu AC.

- Rosas-Pinon Y, Mejia A, Diaz-Ruiz G, Aguilar MI, Sanchez-Nieto S, Rivero-Cruz JF. 2012. Ethnobotanical survey and antibacterial activity of plants used in the Altiplane region of Mexico for the treatment of oral cavity infections. J Ethnopharmacol. 141:860–865.

- Salas L, Rivas G. 2001. Dentistry of the Mayan people. Rev ADM. 58:105–107.

- Salgado AD, Maia JL, Pereira SL, de Lemos TL, Mota OM. 2006. Antiplaque and antigingivitis effects of a gel containing Punica granatum Linn extract: a double-blind clinical study in humans. J Appl Oral Sci. 14:162–166.

- Sanchez-Miranda E, Lemus-Bautista J, Perez S, Perez-Ramos J. 2013. Effect of kramecyne on the inflammatory response in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated peritoneal macrophages. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013:762020

- Santana K, Rey Y, Rodriguez E, Silva M, Rodriguez A. 2015. Applications of natural and traditional medicine in stomatological prosthesis emergencies. AMC. 19:288–296.

- Seo SH, Lee SH, Cha PH, Kim MY, Min d. S, Choi KY. 2016. Polygonum aviculare L. and its active compounds, quercitrin hydrate, caffeic acid, and rutin, activate the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and induce cutaneous wound healing. Phytother Res. 30:848–854.

- Shah R, Gayathri G, Mehta D. 2015. Application of herbal products in management of periodontal diseases: a mini review. Int J Oral Health Sci. 5:38–44.

- Sinha DJ, Sinha AA. 2014. Natural medicaments in dentistry. Ayu. 35:113–118.

- Srikanth RK, Shashikiran ND, Subba Reddy VV. 2008. Chocolate mouth rinse: Effect on plaque accumulation and mutans streptococci counts when used by children. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 26:67–70.

- Surjushe A, Vasani R, Saple DG. 2008. Aloe vera: a short review. Indian J Dermatol. 53:163–166.

- Taddei-Bringas GA, Santillana-Macedo MA, Romero-Cancio JA, Romero TMB. 1999. [Acceptance and use of medicinal plants in family medicine]. Salud Publica Mex. 41:216–220.

- Taheri JB, Azimi S, Rafieian N, Zanjani HA. 2011. Herbs in dentistry. Int Dent J. 61:287–296.

- Terraciano K. 2010. Three Texts in One: Book XII of the Florentine Codex. Ethnohistory. 57:51–72.

- Valerio LG, Jr, Gonzales GF. 2005. Toxicological aspects of the South American herbs cat's claw (Uncaria tomentosa) and Maca (Lepidium meyenii): a critical synopsis. Toxicol Rev. 24:11–35.

- Van Wyk CW, Olivier A, de Miranda C, van der Bijl P, Grobler-Rabie AF, Chalton DO. 1995. Effect of chilli (Capsicum frutescens) extract on proliferation of oral mucosal fibroblasts. Indian J Exp Biol. 33:244–248.

- Vangipuram S, Jha A, Bhashyam M. 2016. Comparative efficacy of Aloe vera mouthwash and chlorhexidine on periodontal health: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Exp Dent. 8:e442–e447.

- Venkatesh Babu NS, Vivek DK, Ambika G. 2011. Comparative evaluation of chlorhexidine mouthrinse versus cacao bean husk extract mouthrinse as antimicrobial agents in children. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 12:245–249.

- Vieira DR, Amaral FM, Maciel MC, Nascimento FR, Liberio SA, Rodrigues VP. 2014. Plant species used in dental diseases: ethnopharmacology aspects and antimicrobial activity evaluation. J Ethnopharmacol. 155:1441–1449.

- Villar Lopez M, Villavicencio Vargas O. 2001. Manual of phytotherapy. Lima, Peru: OPS/OMS PE.

- Waizel J, Martinez I. 2011. A look at a number of the plants used in Mexico in the treatment of periodontal disorders. Rev ADM. 68:73–88.

- Waldstein A. 2008. Diaspora and Health? Traditional medicine and culture in a Mexican migrant community. Int Migr. 46:95–117.