Abstract

Context

Worldwide access to medication remains a major public health problem that forces pregnant women to self-medicate with several sources, such as medicinal plants. This alternative medicine is increasing in many low- and high-income countries for several reasons.

Objective

This a systematic literature review on the prevalence of herbal use during pregnancy from the World Health Organization (WHO) Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office.

Methods

Cross-sectional studies were searched from January 2011 to June 2021 on PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science. We used the Rayyan website to identify the relevant studies by screening the abstracts and titles. These were followed by reading the full texts to identify the final studies to be included. The data were extracted, and the quality of the studies was assessed using the quality appraisal tool.

Results

Of the 33 studies included in this review, 19 were conducted in Iran, 5 in Saudi Arabia, 4 in Palestine, 2 in Egypt, and 1 each in Oman, Iraq, and Jordan; the prevalence of herbal medicine use among pregnant women varied from 19.2% to 90.2%. Several plants were mentioned for pain management during the pregnancy period. The findings suggest family and friends are major motivating sources for the use of herbal medicine.

Conclusions

The wide variety of herbal products used in this study reflects the traditions and geographic diversity of the region. Despite the importance of literature-based data about the use of herbal medicine, it is necessary to obtain knowledge, attitude, and motivation for herbal consumption among pregnant women.

Introduction

Herbal medicines include herbs, herbal materials, herbal preparations, and finished herbal products, that contain active ingredients that are parts of plants, other plant materials, or combinations of these (World Health Organization [WHO], 2019). Herbal treatment is based on the extract of the whole plant, part of the plant (i.e., leaves, roots, flowers), or a mixture of several herbal compounds. For several years, herbal remedies have been taken as a preventive measure to maintain health and to prevent, relieve, or cure diseases (Pieroni et al. Citation2005). Approximately 80% of the world’s population uses various traditional medicines, including herbal medicines, to diagnose, prevent, and treat disease, and to improve general well-being (Eisenberg et al. Citation1998). This practice is due to the popular belief that herbs are natural and free of any adverse effects compared to conventional medicine (Pieroni et al. Citation2005). Local traditions and social pressure, for example, high costs of drugs and medical visits, as well as insufficient health coverage, could also be the reason behind this practice (Choudhry Citation1997). Herbal medicines are available as non-prescription medicines. Given such ease of access, most women say that they decided to use herbal medicine on their own initiative or on the advice of family and/or friends (Kennedy et al. Citation2016).

In Eastern Mediterranean countries, especially in the Arab world, traditional medicine has always been practised despite the advances in modern medicine. The herbalists and scientific community have become more interested in the concept of traditional Arabic herbal medicine (Azaizeh et al. Citation2010). For example, an exhaustive study including 63 articles in total on Ethnobotanico-pharmacological studies was carried out in Morocco, from 1991 to 2015 (Fakchich and Elachouri Citation2021). Another example of a research study on this subject was conducted with a specific focus on pregnant women, This work was the subject of a systematic review of herbal medicine use during pregnancy in Sub-Saharan Africa (El Hajj and Holst Citation2020). The first trimester of pregnancy is associated with physiological changes including nausea, vomiting, constipation, and gastric problems. In the third trimester, gastroesophageal reflux and uterine contractions are more common. Pregnant women self-medicate by using herbs or herbal remedies to relieve the sympathetic signs of pregnancy (John and Shantakumari Citation2015). For this reason, women have been identified as the major users of medicinal herb products. Its prevalence is up to 60% in developed countries (Hall et al. Citation2011). In addition, a literature search of numerous studies from the Western world reported that the prevalence of herbal medicine use in pregnancy ranged from 1 to 60%. Moreover, the prevalence rates were 58% in the UK (Holst et al. Citation2011), 48% in Italy (Lapi et al. Citation2010), 40% in Norway (Nordeng et al. Citation2011), 34% in Australia (Frawley et al. Citation2013), and 6–9% in the USA and Canada (Moussally et al. Citation2009; Louik et al. Citation2010). These different rates of prevalence depend on geographic location, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and cultural traditions (Illamola et al. Citation2019). In this context, the use of herbs during pregnancy can have deleterious consequences for the mother and fetus. It poses a major challenge for healthcare because most patients are not informed about herbal uses (Bercaw et al. Citation2010).

The main aims of our systematic review were to retrieve primary literature reporting the prevalence of herbal medicines used in pregnancy and the postnatal period, as well as to investigate women’s experiences, motivations, and risk factors associated with the use of herbal medicines during pregnancy.

Methods

The PRISMA checklist was used to guide the reporting of the systematic review. A systematic review protocol was registered by PROSPERO Citation2021 with ID: CRD42021264368.

Eligibility criteria

Original articles in human studies that focused on pregnant or post-natal women based on the cross-sectional survey were considered eligible to be included in this review. Studies are also included if they describe the prevalence, attitudes, or beliefs of women towards herbal medicines or provide information about the use of herbs, and herbal products and therapies during pregnancy, including the type of herbal products, conditions of use, and source of information. We excluded unpublished reports, pilot studies, conference abstracts, opinion pieces, editorials, seminal works, and systematic reviews. Studies were excluded if they focused on women’s use of herbal medicines for other conditions that were not related to maternal health care. Studies that reported the combined use of herbal medicines and drugs were excluded if the data on herbal medicines could not be separated sufficiently, and we excluded animal research.

Information sources and search strategy

Two authors, Afaf Bouqoufi and Laila Lahlou, performed independent searches on PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science for articles published from January 2011 to 2021. The search was conducted using the Boolean operators AND OR which narrowed and widened the search and used a combination of MeSH (medical subjects heading). The following search string was used: “herbal medicine” OR plants OR «traditional medicine» OR herbs OR “herbal therapy” AND pregnancy* with a special focus on different countries from the Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office (EMRO). The regional office of the WHO serves 23 countries and territories in the Middle East, North Africa, the Horn of Africa, and Central Asia. including (Afghanistan, Bahrain, Djibouti, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Algeria, Oman, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, the United Arab Emirates, Palestine, and Yemen) World Health Organization Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office [Internet] Switzerland (Citation2021): WHO; [cited July 5th, 2021]. Available from: http://www.emro.who.int/countries.html

Selection process

We used Rayyan (http://rayyan.qcri.org), a free web and mobile app, that helps expedite the initial screening of abstracts and titles using a process of semi-automation. This was followed by reading the full texts to identify the eligible studies. The references in each article were hand-searched for additional eligible studies. Finally, all articles were imported into Zotero, a bibliographic management software system.

Data collection process and data items

Using eligibility criteria, we extracted data including country of studies, year of publication, participant’s demographics, the prevalence of herbal medicine use, details of herbal medicines used, characteristics of users, maternal conditions treated by herbal medicines, reasons for use, and source of information.

Study risk of bias assessment

The quality of eligible studies was assessed. This process was conducted using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Citation2021 an international research organization based in the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences at the University of Adelaide, South Australia. The purpose of this appraisal is to assess the methodological quality of a study and to determine the extent to which a study has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct, and analysis.

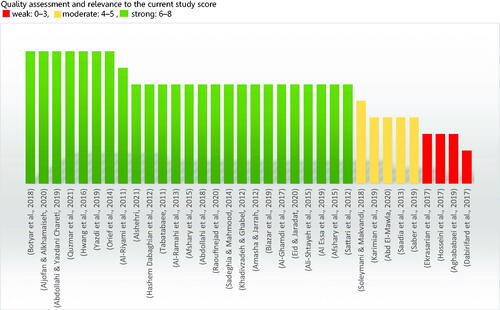

The Quality assessments were conducted by two independent authors (Afaf Bouqoufi and Laila Lahlou) using a recent version of the Joanna Briggs Institute’s critical appraisal tools Checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional Studies. Critical Appraisal Tools | Joanna Briggs Institute. Joanna Briggs Institute’s critical appraisal tools [Internet] | Australia: JBI; [cited 2021 August 31]. Available from: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools. A third author (Youssef Khabbal) was consulted if consensus could not be reached. When information is missing from the studies, we contacted the authors via email. All observational studies were included irrespective of quality score. The articles with missing data were included as long as they presented the prevalence of plant use. The findings of the quality appraisal of eligible studies were reported in .

Results

Study selection

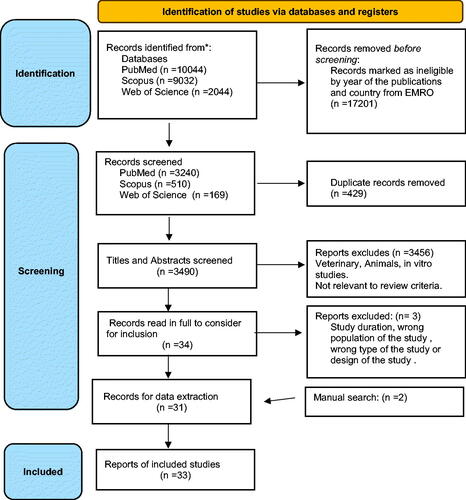

The flowchart of the studies included in this systematic review is illustrated in . The research generated 21,120 articles, of which 429 records were duplicates and were removed: 3459 others were excluded as ineligible after reading their titles or abstracts. Full texts of the remaining 34 records were downloaded and screened or in some cases, the full texts were screened online. After screening through the eligibility criteria, three studies were considered ineligible. A total of 31 studies were found eligible after we added two items in a simple way of research. Therefore, 33 studies were included in the systematic review.

Study characteristics

This present review includes 33 papers in total, of which 19 were conducted in Iran, 5 in Saudi Arabia, 4 in Palestine, 2 in Egypt, and 1 each in Oman, Iraq, and Jordan (). The oldest studies in terms of year of publication (2011) are in Iran (Tableaee 2011) and Oman (Al-Riyami et al. Citation2011). The most recent one is in Palestine (Quzmar et al. Citation2021). All of the included studies used structured or semi-structured survey questionnaires to collect data among pregnant women on the use of herbal medicine during pregnancy, type of herbal products, condition of use, source of information, and referral source. One study from Iran (Khadivzadeh and Ghabel Citation2012) employed the largest sample size of 919 women, whereas the study from Oman (Al-Riyami et al. Citation2011) recruited only 139 participants. The prevalence of the use of herbal medicines among pregnant women in the Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office region varied from 19.2% (Soleymani and Makvandi Citation2018) to 90.2% (Dabirifard et al. Citation2017).

Table 1. User profile of studies on herbal medicine use among pregnant women from the EMRO region.

Risk of bias in studies

The findings of the quality appraisal of eligible studies were reported in . The tool is used to indicate the methodological quality and appropriateness of the observational studies, including cross-sectional studies that were reviewed in this study. It consists of eight items, and we determined the score by counting the asterisks (*) that we gave to each answer to the eight items in the grids, where a high score indicates a higher quality of study and vice versa. The six of the 33 studies were evaluated by the abstract since these articles are in Persian language and we have received no response from their authors to retrieve the full text. Two reviewers completed this process, and where there were discrepancies, a team of reviewers intervened to resolve them.

Results of syntheses

Sociodemographic characteristics of HM users

There was an important association between socio-demographic and obstetric characteristics of women and herbal medicine use. Most women in the included studies were from rural areas, homemakers, and had an educational qualification below graduation (Saadia et al. Citation2013; Afshary et al. Citation2015; Hwang et al. Citation2016; Botyar et al. Citation2018; Abdollahi et al. Citation2018, Citation2019; Yazdi et al. Citation2019; Raoufinejad et al. Citation2020). Most women in the included studies were from rural areas, homemakers, and had an educational qualification below graduation. However, a study from Saudi Arabia and Iran reported that women with a high school diploma or higher (i.e., those with at least 12 years of formal education) and women who were working full-time were significantly more likely to use herbal medicines during pregnancy compared to their less educated and unemployed counterparts (Aljofan & Alkhamaiseh Citation2020; Raoufinejad et al. Citation2020). In some studies, they found a significant relationship between age and the use of herbal medicines, with subjects aged between 20 and 29 years reporting the highest use of herbal medicines (Sattari et al. Citation2012; Orief et al. Citation2014; Botyar et al. Citation2018; Quzmar et al. Citation2021). The number of pregnancies and children also had a significant relationship with herbal medicine use, as women in their first pregnancy were mostly nonusers (Sattari et al. Citation2012; Quzmar et al. Citation2021). Two studies mentioned the association between ethnicities and herbal use (Botyar et al. Citation2018; Yazdi et al. Citation2019).

Most frequently used herbal medicines:

shows that more than half of the studies listed the types of herbal medicines used by pregnant women, whereas the other half failed to indicate the kinds of HMs used by pregnant women (). Overall, 23 studies identified a total of 67 different medicinal plant species used in the traditional treatment of gestational health ailments/symptom complexes throughout EMRO’s region. Some studies have mentioned the use of mixed herbs by pregnant women without indicating the composition of these mixtures (Al-Ramahi et al. Citation2013; Saadia et al. Citation2013; Sadeghia and Mahmood 2014; Hwang et al. Citation2016).

Table 2. Prevalence and pattern of herbal medicine use, referral, and sources of information among pregnant women from the EMRO’s region.

The most commonly used herbs identified were: ginger Zingiber officinale Roscoe (Zingiberaceae), thyme Thymus vulgaris L. (Lamiaceae), peppermint Mentha × piperita L. (Lamiaceae), sage Salvia officinalis L. (Lamiaceae), chamomile Matricaria chamomilla L. (Asteraceae), fenugreek Trigonella foenum-graecum L. (Leguminosae), Black seeds Nigella sativa L. (Ranunculaceae), honey, cinnamon Cinnamomum verum J.Presl (Lauraceae), sour orange blossom Citrus × aurantium L. (Rutaceae), green tea Camellia sinensis (Theaceae), aniseeds Pimpinella anisum L. (Apiaceae), garlic Allium sativum L. (Amaryllidaceae) and cumin Cuminum cyminum L. (Apiaceae). Various studies reported the parts of the plant used, methods of preparation, and routes of administration. Most of the users customarily use diverse plant parts as medicinal agents, including root, bark, fruit, bulbs, whole plants, rhizomes, seeds, flowers, and stems, but leaves were the predominant part used (Sadeghia and Mahmood 2014; Ali-Shtayeh et al. Citation2015; Eid et al. Citation2020). Some of the studies explored the method of preparation of medicinal herbs for treatment. We have observed that the most common methods were infusions/tea, maceration, squeezing, chewing, decoction, bathing, evaporating/inhaling, and ingestion of raw medicinal plant material (Sadeghi and Mahmood Citation2014; Ali-Shtayeh et al. Citation2015; Eid et al. Citation2020). Routes of administration included oral (Al-Ramahi et al. Citation2013, Ali-Shtayeh et al. Citation2015, Raoufinejad et al. Citation2020), topical (Sadeghi and Mahmood Citation2014; Ali-Shtayeh et al. Citation2015; Raoufinejad et al. Citation2020) and intra-vaginal (Al-Ramahi et al. Citation2013). Furthermore, oral ingestion was the most common method and was suggested in numerous studies. In some studies, they found a significant relationship between the trimester of pregnancy and the use of herbal medicines (Saadia et al. Citation2013; Afshary et al. Citation2015; Yazdi et al. Citation2019; Al Essa et al. Citation2019; Alshehri and Alshehri Citation2021). The majority of the studies reported the highest use of herbs during the third trimester, with the frequency varying from 15.3% to 60.0% (Al-Riyami et al. Citation2011; Tabatabaee Citation2011; Orief et al.Citation2014; Abdollahi et al. Citation2019; Al Essa et al. Citation2019; Saber et al. Citation2019; Yazdi et al. Citation2019; Aljofan and Alkhamaiseh Citation2020; Alshehri and Alshehri Citation2021).

Reasons for use and sources of information

Users of herbal medicines during pregnancy had several reasons for consuming these medicines. Informants in most of the studies reported the use of herbal medicines to alleviate pregnancy-associated symptoms. The herbs were most frequently used to treat gastrointestinal disorders such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, bloating, flatulence, and stomach aches, followed by cold and flu symptoms and stretch marks. Although some others reported this use for stimulation of labor, and facilitation of childbirth. Other uses were specifically to enhance neonates intelligence and promote fetal health. Finally, skin problems, sleep disorders, and weight loss are the lesser common reasons that we have noted among some users. Finally, reported traditional indications of the most frequently used herbal medicines are shown in (). The quality and source of information received on herbal medicine automatically influence the choice of treatment for maternal illnesses. Nearly half of the reviewed materials disclosed the sources from which pregnant women received information about herbal medicines. The principal sources were family and friends respectively, for the studies (TableaTableaee 2011; Hashem Dabaghian et al. Citation2012; Amasha and Jarrah Citation2012; Khadivzadeh and Ghabel Citation2012; Hwang et al. Citation2016; Al-Ghamdi et al. Citation2017; Abdollahi et al. Citation2019; Al Essa et al. Citation2019; Yazdi et al. Citation2019; Eid et al. Citation2020; Raoufinejad et al. Citation2020; Quzmar et al. Citation2021). Some women decided in-person to use herbal medicines in pregnancy, labor, or postpartum (Sattari et al. Citation2012; Al-Ghamdi et al. Citation2017; Al Essa et al. Citation2019; Eid et al. Citation2020; Raoufinejad et al. Citation2020; Alshehri and Alshehri Citation2021). On the other hand, some expectant women indicated health professionals such as physicians, pharmacists, and nurses as a source of herbal medicine information (Amasha and Jarrah Citation2012; Hashem Dabaghian et al. Citation2012; Orief et al. Citation2014; Hwang et al. Citation2016; Eid et al. Citation2020; Raoufinejad et al. Citation2020; Quzmar et al. Citation2021; Alshehri and Alshehri Citation2021). Other users qbtainedtheir recommendations from the bush, traditional herbalists, the internet, social media, newspapers, radio, television, and books.

The motivation for HM utilization

The time required to decide to use HM varied greatly depending on their health needs, current knowledge, and habits. According to some studies, women’s personal preferences influenced their choices and decisions. A study from Iran (Abdollahi et al. Citation2018) reported women’s perception of the applied herb’s efficacy, and 41.2% of users were fully satisfied. Women who used HM before and during gestation seemed more probable to use it throughout labor and after delivery as for example, in a study from Saudi Arabia (Afshary et al. Citation2015). The primary motivations to utilize herbal medicines or herbal remedies during pregnancy are that they had been taken before the pregnancy and to save money on healthcare costs. Others believe they are safe and not dangerous herbs for pregnant women and embryos (Amasha and Jarrah Citation2012; Khadivzadeh and Ghabel Citation2012; Sattari et al. Citation2012). Moreover, some women made decisions based on their health conditions, and according to their experiences. In Palestine, 21.0% of the participants reported that they used HM because medical therapies failed to succeed. Nearly 58% used HM because it was more accessible, compared to medical therapy. Other participants used CAM because of its common use and recommendation in their culture (Quzmar et al. Citation2021).

Discussion

To our knowledge, our work represents the first systematic review to identify the prevalence, motivation, and factors associated with herbal use among pregnant women in EMRO countries. This current review included 23 cross-sectional studies that included data on 13,021 women involved in the respective studies.

The findings suggest that the prevalence of herbal medicine use among pregnant women from the EMRO countries varied from 19.2% to 90.2%. This finding broadly supports the work of other studies in this area, such as a recently published systematic review by Ahmed et al. (Citation2018) of 50 studies, including a total of 22404 African pregnant or lactating women, showing that the average prevalence of herbal medicine use during pregnancy among the different African regions was between 32% (in Central Africa) and 45% (in East Africa) (Ahmed et al. Citation2018). Additionally, current studies have highlighted the difference in the prevalence of herbal medicine among pregnant women, 59.3% in Yamen (Ahmed et al. Citation2022), 51.2%-65.6% in Ethiopia (Belayneh et al. Citation2022; Wake and Fitie Citation2022), 71.80% in Bangladesh (Jahan et al. Citation2022), and 67.45% in Morocco (Kamel et al. Citation2022). To date, many studies have investigated the impact of herbal medicine on pregnant women in another geographic area, a systematic review of Asian countries reported that, in total, 1283 out of 2729 (47.01%) women used at least one herbal medicine during their pregnancy (Ahmed et al. Citation2017). In Europe, North, and South America systematic review reported that, in total, 29.3% of the women (n = 2673) used herbal medicines during pregnancy (Kennedy et al. Citation2016). Based on the survey of the literature related to our topic, some research focuses on the prevalence of herbal medicine, such as a preliminary study of pregnant women, which reported a prevalence of 57.3% (Barnes et al. Citation2022), a further study found that the prevalence total was 65.71% of women that used Chinese herbal medicine formulas, including 26.13% during pregnancy and 55.63% after delivery (Xiong et al. Citation2023).

These findings suggest that herbal medicine use during pregnancy is not only common in EMRO’s countries as an entrenched part of the culture but is also common elsewhere in developed societies where traditions do not directly impact this use. Regarding the use of herbal medicine in pregnancy, most women in the studies were from rural areas, homemakers, and had an educational qualification below graduation. We found that there was a strong interplay of sociodemographic between the obstetric characteristics of women and herbal medicine use. This was in accordance with studies outside of EMRO countries that reported higher usage of herbs among women from rural areas that were less educated, these findings have been documented in previous studies in several countries around the world such as Kenya (Mothupi Citation2014), Bangladesh (Jahan et al. Citation2022), Uganda (Kaadaaga et al. Citation2014), and Ethiopia (Belayneh et al. Citation2022). In addition, it was observed that some of those women perceived that they had better knowledge about herbal medicine than the physicians/nurses and would persist in using it against medical advice. In contrast, a study in Norway and the United States shows a difference in the characteristics of herbal medicine users, the differences can be explained by the socioeconomic levels of families. The rich consult with their doctor before use or otherwise ensure adequate information about the benefits and side-effects of the herbal product (Nordeng and Havnen Citation2004; Bercaw et al. Citation2010).

The data of our systematic review contradict the widely-held hypothesis that uneducated housewives living in rural regions are the most probable users of high-risk, untested products, such as herbal or plant-based products. However, in addition to the current results, a previous study examining the prevalence of use and costs of herbal medicines in northern Scotland demonstrated that educated women were more likely to use this medicine (Pallivalapila et al. Citation2015). Similar findings are also reported in these studies (Mothupi Citation2014; Hwang et al. Citation2016). Based on WHO findings, two-thirds of women in low-middle-income countries (LMICs) use herbal medicines as their primary source of health care (Crockett et al. Citation2020). Some research studies (Botyar et al. Citation2018; Yazdi et al. Citation2019) reported the relationship between ethnicities and the use of herbal medicines, these studies indicated that the Arab population used traditional medicine more than the Fars population during pregnancy. However, there is a lack of data on the use of herbal medicines among different ethnic populations worldwide (Graham et al. Citation2005; Rashrash et al. Citation2017).

The current survey showed that pregnant women from EMRO’s region use a wide diversity of herbal medicine, and a total of 65 different medicinal plant species used in the traditional treatment of gestational health are reported. Generally, the African continent is known for its rich biodiversity. This species richness was reflected in the systematic review by Ahmed et al. (Citation2018) in which the number of cited plant species varied from study to study, and 274 medicinal plants were reported to be used by African pregnant women. The following herbs were the most commonly used: (Zingiber officinale), (Thymus vulgaris), (Mentha × piperita), (Salvia officinalis), (Matricaria chamomilla), (Trigonella foenum-graecum), (Nigella sativa), honey, (Cinnamomum verum), (Citrus × aurantium), (Camellia sinensis), (Pimpinella anisum), (Allium sativum) and (Cuminum cyminum). The frequently used herbs in most studies were similar to other studies from the EMRO. In sub-Saharan Africa, the top herbal medicines cited in the studies were Zingiber officinale, Allium sativum, Cucurbita pepo (Cucurbitaceae), Ricinus communis (Euphorbiaceae), Vernonia amygdalina Debile (Asteraceae) and Garcinia kola Heckel (Clusiaceae). Zingiber officinale was the most common species for the treatment of pregnancy-induced nausea and vomiting and was reported in 15 studies (El Hajj et al. Citation2020). In contrast, due to differences in culture, traditions, and climate, it is expected that herbal medicines used during pregnancy vary across countries and regions. The herbs most commonly used in Australia (Barnes et al. Citation2022), Norway (Nordeng and Havnen Citation2004), and Tuscany were Rubus idaeus L. (Rosaceae), Foeniculum vulgare, and Hypericum perforatum L. (Hypericaceae). A good variety of reasons were proffered for using HM. The most common reason was to alleviate pregnancy-associated symptoms. The herbs were most frequently used to treat gastrointestinal disorders such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, bloating, flatulence, and stomach aches, followed by cold and flu symptoms. Others reported this use for stimulation of labor or facilitation of labor and delivery. Other uses were specifically to enhance neonates’ intelligence and promote fetal health. Finally, skin problems, sleep disorders, and weight loss are a few reasons that we have noted among some users. The quality and source of information obtained on herbal medicine immediately impact the choice of therapy for maternal disorders.

Family and friends were the common referral/information sources in the studies (Tablea 2011; Hashem Dabaghian et al. Citation2012; Amasha and Jarrah Citation2012; Khadivzadeh and Ghabel Citation2012; Hwang et al. Citation2016; Al-Ghamdi et al. Citation2017; Abdollahi et al. Citation2019; Al Essa et al. Citation2019; Yazdi et al. Citation2019; Eid et al. Citation2020; Raoufinejad et al. Citation2020; Quzmar et al. Citation2021). Some women decide to use herbal medicines in-person during pregnancy, labor, or postpartum. Some pregnant women, on the other hand, mentioned health professionals such as physicians, pharmacists, and nurses as source of information on herbal medicines. To provide optimal care and counseling for patients who use herbal drugs, pharmacists need to be well-informed about the use and safety of herbs and should update their knowledge. This can be achieved by providing education and training to practicing pharmacists by organizing continuing medical education programs focused on the efficacy, potential risks, possible herb-drug interactions and consequences, and the key principles applied to the administration of herbs during pregnancy. We would also advise that physicians specifically ask about herb usage and document it in the patient record. Pregnant mothers should be informed of the potential risks posed by herbs during pregnancy and advised to avoid their use. Other users obtained their recommendations from the bush, or traditional herbalists, the internet, social media, newspapers, radio, television, and books. In these cases, it is necessary to exploit this point to carry out awareness and create preventive programs, including a media campaign that uses digital conversational advertisements broadcast on sites consulted by pregnant women or those planning to become pregnant, as well as banners and videos. The multiplicity of the points of contact will ensure the visibility of this type of message to the target audience, e.g., building on the community approach with pair training that will facilitate the dissemination of the message in the community.

The time taken to decide to use HM varied considerably depending on women’s health needs, available information, and preferences. Some studies discovered that women’s personal preferences motivated the choices and decisions they made. For most users, HM was the ideal medicine for solving pregnancy problems, inducing labor, and treating postpartum complications (Bercaw et al. Citation2010). Women who used HM during pregnancy and pre/pregnancy were more likely to use it during labor and after delivery. The most common reasons for using herbal medicines or herbal remedies during pregnancy are that they were using them before pregnancy, they had costly medical expenses, they are safe and harmless herbs for the mother and fetus, and they used HM because it was more accessible, compared to medical therapy. These findings were reported in other locations (Agyei-Baffour et al. Citation2017; Sumankuuro et al. Citation2017; Ahmed et al. Citation2022; Elba et al. Citation2022). Moreover, some women made decisions based on their health conditions, and their experiences. The participants used herbal medicine because of its common use and recommendation in their culture. These findings were reported in other studies (Tripathi et al. Citation2013).

Limitations of the studies

This review contains some limitations, such as the fact that the prevalence identified may not represent the true prevalence due to the variations in the studies. Also, we have found that the majority of the published literature is predominantly from one country.

Conclusions

Overall, our systematic review is one of the first reports to shed light on the prevalence, use pattern, and perceptions of herbal medicine use among pregnant women in the EMRO’s region. A low-disclosure study of herbal medicine use among pregnant women in Morocco has also been shown in the present review. Despite the importance of literature data about the use of herbal remedies, it is necessary to obtain good knowledge, attitude, and motivation for herbal consumption among women. Healthcare professionals and researchers can disseminate the results of this study to choose the best ways to hide the message in the context of prevention. Herbal medicines may be natural, but they do contain pharmacologically active ingredients. Due to the limited number of studies, it is recommended that future studies focus on safety and the effects of herbal medicines on pregnancy outcomes.

Author contribution

AB, LL conceived of the study and compiled the data used in analyses, conducted analyses and drafted the manuscript. FA and YK assisted within the perpetration of the data and provided feedback for this manuscript. MA, MO majorly contributed to the critical discussion and revision of the manuscript and helped. YK supervised the findings of this work. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like all the researchers whose works were used in the present study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abd El-Mawla AMA. 2020. Prevalence and use of medicinal plants among pregnant women in Assiut Governorate. Bull Pharm Sci. 43(1):73–78.

- Abdollahi F, Chareti J, Abdollahi F, Chareti JY. 2019. The relationship between women’s characteristics and herbal medicines use during pregnancy. Women Health. 59(6):579–590. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2017.1421285.

- Abdollahi F, Khani S, Charati J, Abdollahi F, Khani S, Charati JY. 2018. Prevalence and related factors to herbal medicines use among pregnant females. Jundishapur J Nat Pharmaceu Prod. 13(3):e13785.

- Afshary P, Mohammadi S, Najar S, Pajohideh Z, Tabesh H. 2015. Prevalence and causes of self-medication in pregnant women referring to health centers in southern of Iran. Int J Pharmaceu Scie Res. 6:612–619.

- Aghababaei S, Soltanian AR, Sharifi S, Torkzaban E, Refaei M. 2019. Investigating the factors related to severity of nausea and vomiting during pregnancy and how it is controlled by pregnant women in Hamadan, 2014. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 21(11):23–31.

- Agyei-Baffour P, Kudolo A, Quansah DY, Boateng D. 2017. Integrating herbal medicine into mainstream healthcare in Ghana: clients’ acceptability, perceptions and disclosure of use. BMC Complement Alter Med. 17(1):513.

- Agyei-Baffour P, Kudolo A, Quansah DY, Boateng D. 2017. Integrating herbal medicine into mainstream healthcare in Ghana: clients’ acceptability, perceptions and disclosure of use. BMC Complement Altern Med. 17(1):513. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-2025-4.

- Ahmed M, Hwang JH, Ali MN, Al-Ahnoumy S, Han D. 2022. Irrational use of selected herbal medicines during pregnancy: a pharmacoepidemiological evidence from Yemen. Front Pharmacol. 13:926449. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.926449.

- Ahmed M, Hwang JH, Choi S, Han D. 2017. Safety classification of herbal medicines used among pregnant women in Asian countries: a systematic review. BMC Complement Alter Med. 17(1):489.

- Ahmed SM, Nordeng H, Sundby J, Aragaw YA, de Boer HJ. 2018. The use of medicinal plants by pregnant women in Africa: a systematic review. J Ethnopharmacol. 224:297–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2018.05.032.

- Al Essa M, Alissa A, Alanizi A, Bustami R, Almogbel F, Alzuwayed O, Abo Moti M, Alsadoun N, Alshammari W, Albekairy A, et al. 2019. Pregnant women’s use and attitude toward herbal, vitamin, and mineral supplements in an academic tertiary care center, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm J. 27(1):138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2018.09.007.

- Al-Ghamdi S, Aldossari K, Al-Zahrani J, Al-Shaalan F, Al-Sharif S, Al-Khurayji H, Al-Swayeh A, et al. 2017. Prevalence, knowledge and attitudes toward herbal medication use by Saudi women in the central region during pregnancy, during labor and after delivery. BMC Complement Alter Med. 17(1):196.

- Ali-Shtayeh M, Jamous R, Jamous R, Ali-Shtayeh MS, Jamous RM, Jamous RM. 2015. Plants used during pregnancy, childbirth, postpartum and infant healthcare in Palestine. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 21(2):84–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2015.03.004.

- Aljofan M, Alkhamaiseh S. 2020. Prevalence and factors influencing use of herbal medicines during pregnancy in hail, Saudi Arabia a cross-sectional study. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 20(1):e71–e76. doi: 10.18295/squmj.2020.20.01.010.

- Al-Ramahi R, Jaradat N, Adawi D, Al-Ramahi R, Jaradat N, Adawi D. 2013. Use of herbal medicines during pregnancy in a group of Palestinian women. J Ethnopharmacol. 150(1):79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.07.041.

- Al-Riyami IM, Al-Busaidy IQ, Al-Zakwani IS. 2011. Medication use during pregnancy in Omani women. Int J Clin Pharm. 33(4):634–641. doi: 10.1007/s11096-011-9517-y.

- Alshehri N, Alshehri NA. 2021. The use of herbs to induce labor among pregnant women and associated factors: a cross-sectional study. Int J Med Res Heal Sci. 10(2):79–87.

- Amasha H, Jarrah S. 2012. The use of home remedies by pregnant mothers as a treatment of pregnancy related complaints: an exploratory study. Med J Cairo Uni. 80:673–680.

- Azaizeh H, Saad B, Cooper E, Said O. 2010. Traditional Arabic and Islamic medicine, a re-emerging health Aid. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 7(4):419–424. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nen039.

- Barnes LAJ, Rolfe MI, Barclay L, McCaffery K, Aslani P. 2022. Women’s reasons for taking complementary medicine products in pregnancy and lactation: results from a national Australian survey. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 49:101673. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2022.101673.

- Belayneh YM, Yoseph T, Ahmed S. 2022. A cross-sectional study of herbal medicine use and contributing factors among pregnant women on antenatal care follow-up at Dessie Referral Hospital, Northeast Ethiopia. BMC Complement Med Ther. 22(1):146. doi: 10.1186/s12906-022-03628-8.

- Bercaw J, Maheshwari B, Sangi-Haghpeykar H. 2010. The use during pregnancy of prescription, over-the-counter, and alternative medications among Hispanic women. Birth. 37(3):211–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2010.00408.x.

- Biazar G, Nabi B, Sedighinejad A, Moghadam A, Farzi F, Atrkarroushan Z, Mirblook F, Mirmansouri L, Biazar Gelareh, Nabi BN. 2019. Herbal products use during pregnancy in north of Iran. Int J Women’s Health Reprod Sci. 7(1):134–137. doi: 10.15296/ijwhr.2019.21.

- Botyar M, Kashanian M, Abadi ZRH, Noor MH, Khoramroudi R, Monfaredi M, Nasehe G. 2018. A comparison of the frequency, risk factors, and type of self-medication in pregnant and nonpregnant women presenting to Shahid Akbar Abadi Teaching Hospital in Tehran. J Family Med Prim Care. 7(1):124–129. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_227_17.

- Choudhry UK. 1997. Traditional practices of women from India: pregnancy, childbirth, and newborn care. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 26(5):533–539. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1997.tb02156.x.

- Crockett J, Sumankuuro J, Soyen C, Ibrahim M, Ngmenkpieo F, Wulifan JK. 2020. Women’s motivation and associated factors for herbal medicine use during pregnancy and childbirth: a systematic review. Health. 12(06):572–597. doi: 10.4236/health.2020.126044.

- Dabirifard M, Maghsoudi Z, Dabirifard S, Salmani N. 2017. Frequency, causes and how to use medicinal herbs during pregnancy. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 20(4):66–75.

- Eid A, Jaradat N, Eid AM, Jaradat N. 2020. Public Knowledge, attitude, and practice on herbal remedies used during pregnancy and lactation in West Bank Palestine. Front Pharmacol. 11:46. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00046.

- Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, Appel S, Wilkey S, Van Rompay M, Kessler RC. 1998. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997 results of a follow-up national survey. Jama. 280(18):1569–1575. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.18.1569.

- Ekrasarian S, Rostami F, Charati JY, Abdollahi F. 2017. Use of medicinal plants during pregnancy in pregnant women in Sari, Iran. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 26(144):341–345.

- El Hajj M, Holst L. 2020. Herbal medicine use during Pregnancy: a review of the literature with a special focus on sub-saharan africa. Front Pharmacol. 11:866. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00866.

- El Hajj M, Sitali DC, Vwalika B, Holst L. 2020. Herbal medicine use among pregnant women attending antenatal clinics in Lusaka Province, Zambia: a cross-sectional, multicentre study. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 40:101218. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2020.101218.

- Elba F, Hilmanto D, Poddar S. 2022. Factors influencing the use of herbal medications during pregnancy at Public Health Center, Indonesia. J Public Health Res. 11(4):227990362211399. 22799036221139940. doi: 10.1177/22799036221139939.

- Fakchich J, Elachouri M. 2021. An overview on ethnobotanico-pharmacological studies carried out in Morocco, from 1991 to 2015: systematic review (part 1). J Ethnopharmacol. 267:113200. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.113200.

- Frawley J, Adams J, Sibbritt D, Steel A, Broom A, Gallois C. 2013. Prevalence and determinants of complementary and alternative medicine use during pregnancy: results from a nationally representative sample of Australian pregnant women. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 53(4):347–352. doi: 10.1111/ajo.12056.

- Graham RE, Ahn AC, Davis RB, O’Connor BB, Eisenberg DM, Phillips RS. 2005. Use of complementary and alternative medical therapies among racial and ethnic minority adults: results from the 2002 National Health Interview Survey. J Natl Med Assoc. 97(4):535–545.

- Hall HG, Griffiths DL, McKenna LG. 2011. The use of complementary and alternative medicine by pregnant women: a literature review. Midwifery. 27(6):817–824. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2010.08.007.

- Hashem Dabaghian F, Abdollahi Fard M, Shojaei A, Kianbakht S, Zafarghandi N, Goushegir A. 2012. Use and attitude on herbal medicine in a group of pregnant women in Tehran. J Med Plan. 11(41):22–33.

- Holst L, Wright D, Haavik S, Nordeng H. 2011. Safety and efficacy of herbal remedies in obstetrics-review and clinical implications. Midwifery. 27(1):80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2009.05.010.

- Hosseini SH, Rajabzadeh R, Nosrati H, Naseri F, Toroski M, Mohaddes Hakkak H, Ayati MH. 2017. Prevalence of medicinal herbs consumption in pregnant women referring to Bojnurd health care centers. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 20(9):33–40. doi: 10.22038/IJOGI.2017.9953.

- Hwang JH, Kim Y-R, Ahmed M, Choi S, Al-Hammadi NQ, Widad NM, Han D. 2016. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in pregnancy: a cross-sectional survey on Iraqi women. BMC Complement Altern Med. 16(1):191. doi: 10.1186/s12906-016-1167-0.

- Illamola SM, Amaeze OU, Krepkova LV, Birnbaum AK, Karanam A, Job KM, Bortnikova VV, Sherwin CMT, Enioutina EY. 2019. Use of herbal medicine by pregnant women: what physicians need to know. Front Pharmacol. 10:1483. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01483.

- Jahan S, Mozumder ZM, Shill DK. 2022. Use of herbal medicines during pregnancy in a group of Bangladeshi women. Heliyon. 8(1):e08854. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e08854.

- Joanna Briggs Institute’s critical appraisal tools. 2021. [Internet] Australia: JBI; [cited 2021 August 31]. Available from: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools.

- John LJ, Shantakumari N. 2015. Herbal medicines use during pregnancy: a review from the Middle East. Oman Med J. 30(4):229–236. doi: 10.5001/omj.2015.48.

- Kaadaaga HF, Ajeani J, Ononge S, Alele PE, Nakasujja N, Manabe YC, Kakaire O. 2014. Prevalence and factors associated with use of herbal medicine among women attending an infertility clinic in Uganda. BMC Complement Altern Med. 14(1):27. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-27.

- Kamel N, El Boullani R, Cherrah Y. 2022. Use of medicinal plants during pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum in Southern Morocco. Healthcare. 10(11):2327. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10112327.

- Karimian Z, Hasani M, Afshar B, Lale H, Abedini R, Mirzaie N, Taghian N. 2019. Prevalence of self-medication of medicinal plants in treatment of common pregnancy problems in women referred to health centers in Kashan. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 21(12):23–28.

- Kennedy DA, Lupattelli A, Koren G, Nordeng H. 2016. Safety classification of herbal medicines used in pregnancy in a multinational study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 16:102. doi: 10.1186/s12906-016-1079-z.

- Khadivzadeh T, Ghabel M. 2012. Complementary and alternative medicine use in pregnancy in Mashhad. Iran, 2007-8. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 17(4):263–269.

- Lapi F, Vannacci A, Moschini M, Cipollini F, Morsuillo M, Gallo E, Banchelli G, Cecchi E, Di Pirro M, Giovannini MG, et al. 2010. Use, attitudes and knowledge of complementary and alternative drugs (CADs) among pregnant women: a preliminary survey in Tuscany. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 7(4):477–486. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nen031.

- Louik C, Gardiner P, Kelley K, Mitchell AA. 2010. Use of herbal treatments in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 202(5):439.e1–439.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.055.

- Marcus DM, Snodgrass WR. 2005. Do No Harm: avoidance of herbal medicines during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 105(5 Pt 1):1119–1122. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000158858.79134.ea.

- Mothupi MC. 2014. Use of herbal medicine during pregnancy among women with access to public healthcare in Nairobi, Kenya: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Complement Altern Med. 14:432. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-432.

- Moussally K, Oraichi D, Bérard A. 2009. Herbal products use during pregnancy: prevalence and predictors. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 18(6):454–461. doi: 10.1002/pds.1731.

- Nordeng H, Bayne K, Havnen GC, Paulsen BS. 2011. Use of herbal drugs during pregnancy among 600 Norwegian women in relation to concurrent use of conventional drugs and pregnancy outcome. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 17(3):147–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2010.09.002.

- Nordeng H, Havnen GC. 2004. Use of herbal drugs in pregnancy: a survey among 400 Norwegian women. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 13(6):371–380. doi: 10.1002/pds.945.

- Orief Y, Farghaly NF, Ibrahim MIA, Orief Y, Farghaly N, Ibrahim M. 2014. Use of herbal medicines among pregnant women attending family health centers in Alexandria. Middle East Fer Soc J. 19(1):42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.mefs.2012.02.007.

- Pallivalapila AR, Stewart D, Shetty A, Pande B, Singh R, McLay JS. 2015. Use of complementary and alternative medicines during the third trimester. Obstet Gynecol. 125(1):204–211. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000596.

- Pieroni A, Price LL, Vandebroek I. 2005. Welcome to the journal of ethnobiology and ethnomedicine. J Ethnobiology Ethnomedicine. 1(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-1-1.

- PROSPERO International prospective register of systematic reviews 2021 [Internet] |USA CRD. August 31]. Available from: [cited 2021. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD420212643689.

- Quzmar Y, Istiatieh Z, Nabulsi H, Zyoud S, Al-Jabi S, Quzmar Y, Istiatieh Z, Nabulsi H, Zyoud SH, Al-Jabi SW. 2021. The use of complementary and alternative medicine during pregnancy: a cross-sectional study from Palestine. BMC Complement Med Ther. 21(1):108. doi: 10.1186/s12906-021-03280-8.

- Raoufinejad K, Gholami K, Javadi M, Rajabi M, Torkamandi H, Moeini A, Mohebbi N. 2020. A retrospective cohort study of herbal medicines use during pregnancy: prevalence, adverse reactions, and newborn outcomes. Trad Integ Med. 5(2):70–85.

- Rashrash M, Schommer JC, Brown LM. 2017. Prevalence and predictors of herbal medicine use among adults in the United States. J Patient Exp. 4(3):108–113. doi: 10.1177/2374373517706612.

- Saadia Z, Roshdy S, Sagir F, Abidin S. 2013. Dietary practices of Saudi women during puerperium. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 39(4):799–805. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2012.02035.x.

- Saber M, Khanjani N, Zamanian M, Safinejad H, Shahinfar S, Borhani M. 2019. Use of medicinal plants and synthetic medicines by pregnant women in Kerman. Iran. Arch Iran Med. 22(7):390–393.

- Sadeghi Z, Mahmood A. 2014. Ethno-gynecological knowledge of medicinal plants used by Baluch tribes, in southeast Baluchistan, Iran. Revista Brasileira Farmaco. 24(6):706–715. doi: 10.1016/j.bjp.2014.11.006.

- Sattari M, Dilmaghanizadeh M, Hamishehkar H, Mashayekhi S, Sattari M, Dilmaghanizadeh M, Hamishehkar H, Mashayekhi SO. 2012. Self-reported use and attitudes regarding herbal medicine safety during pregnancy in Iran. Jundishapur J Nat Pharm Prod. 7(2):45–49. doi: 10.17795/jjnpp-3416.

- Soleymani S, Makvandi S. 2018. Rate of herbal medicines used during pregnancy and some related factors in women of Ahvaz, Iran: 2017. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 21(5):80–86.

- Sumankuuro J, Crockett J, Wang S. 2017. Maternal health care initiatives: causes of morbidities and mortalities in two rural districts of Upper West Region, Ghana. PLoS One. 12(8):e0183644. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183644.

- Tabatabaee M. 2011. Use of herbal medicine among pregnant women referring to Valiasr Hospital in Kazeroon, Fars, South of Iran. J Med Plants. 10(37):96–108.

- Tripathi V, Stanton C, Anderson FWJ. 2013. Traditional preparations used as uterotonics in Sub-Saharan Africa and their pharmacologic effects. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 120(1):16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.06.020.

- Wake GE, Fitie GW. 2022. Magnitude and determinant factors of herbal medicine utilization among mothers attending their antenatal care at public health institutions in Debre Berhan Town, Ethiopia. Front Public Health. 10:883053. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.883053.

- World Health Organization Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office [Internet] | Switzerland: WHO. 2021. July 05]. Available from: [cited http://www.emro.who.int/countries.html.

- Xiong Y, Liu C, Li M, Qin X, Guo J, Wei W, Yao G, Qian Y, Ye L, Liu H, et al. 2023. The use of Chinese herbal medicines throughout the pregnancy life course and their safety profiles: a population-based cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 5(5):100907.,. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2023.100907.

- Yazdi N, Salehi A, Vojoud M, Sharifi MH, Hoseinkhani A. 2019. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in pregnant women: A cross-sectional survey in the south of Iran. J Integr Med. 17(6):392–395. doi: 10.1016/j.joim.2019.09.003.