?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Context

Although pharmaceutical equipment and medical supplies play a vital role in the quality of traditional medicines, they have not received much attention from stakeholders and researchers nationally and internationally.

Objective

This study assesses traditional healers’ knowledge and utilization of pharmaceutical equipment and medical supplies in the Amhara region, North West Ethiopia.

Materials and methods

A quantitative cross-sectional study was conducted on 70 traditional healers. The data were collected using an interview-based questionnaire. The collected data were checked and entered into Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 25.0 for analysis. The results were presented as percentages. The association between socio-demographic characteristics and traditional healers’ knowledge of pharmaceutical equipment and medical supplies was examined using Pearson’s Chi-squares test.

Results

About 90% of traditional healers had information about pharmaceutical equipment and medical supplies, and currently 80% of them used different pharmaceutical equipment and medical supplies individually and in combination with traditional equipment. Although most traditional healers used different pharmaceutical equipment and medical supplies, only 13.3% of them used equipment and supplies a day. Only 15% of traditional healers continuously cleaned their equipment. None of the socio-demographic variables were significantly associated to the knowledge of pharmaceutical equipment and medical supplies.

Discussion and Conclusions

Pharmaceutical equipment and medical supplies used by traditional healers was inconsistent, mainly associated with their habit of using self-prepared and home-available equipment. Moreover, the checkup status of compounding equipment was poor. As Traditional healers provide high-patient care services, emphasis should be given to improving their preparation and treatment strategies.

Keywords:

Introduction

Traditional healers (THs) have a particular skill in treating specific types of complaints and might have gained a reputation in their communities in Africa, for example, Ethiopia (Birhan et al. Citation2011), or Cameroon (Agbor and Naidoo Citation2011) and Asia such as Thailand (Junsongduang et al. Citation2020), Saudi Arabia (Al-Yahia et al. Citation2017), and Nepal (Pandey et al. Citation2023). Traditional treatment occupies an important place in the healthcare systems in Ethiopia; it is estimated that it meets 80% of primary healthcare needs (Birhan et al. Citation2011; Wassie et al. Citation2015; Aferu et al. Citation2022). The 2014–2023 strategy for traditional medicines (TMs) from the World Health Organization (WHO) posits that traditional treatments and herbal medicines are the main sources of healthcare for millions of people (Junsongduang et al. Citation2020). THs prepare different forms of TMs based on the principle of compounding, as they grind, mix, combine, and formulate dosage forms. Additionally, the doses of the preparations are patient-need-driven and specific to each of the cases. If they obtain training based on sound compounding processes, their TMs quality will grow (Galson Citation2003).

Compounding personnel must follow established standard operating procedures for the upkeep, cleaning, and use of equipment, supported by the manufacturer’s recommendations (Gudeman et al. Citation2013; USP 30/NF 335. 2015). Inappropriately compounded medication results in the administration of insufficient doses and contaminated drugs, which can cause ineffectiveness or toxicity (Assefa et al. Citation2022).

The National Strategic Plan for the development and integration of TMs adheres to the recommendation of the organization to valourize TMs, despite the sector being plagued with numerous constraints. The main constraints are inadequate institutional support and insufficient technology for postharvest and pre-processing purposes adapted productively and effectively (Fokunang et al. Citation2011). It is challenging to stop irrational medicine use, packing, and compounding due to disease diagnosis, medicine preparation, and patient administration are all done by THs (Ofori-Asenso and Agyeman Citation2016; McBane et al. Citation2019). As a result, the Ministry of Health and research institutes should give special consideration to capacitating THs in order to enhance their compounding and TM practices, primarily by assessing and instructing them on how to use appropriate medical supplies (MSs) and pharmaceutical equipment (PE). These goods should be made of suitable materials to prevent surface reactivity and additive effects on medicines (WHO 2010). In addition, PE should be cleaned, stored, and sanitized or sterilized to prevent contamination, which can alter the quality of medicine (Kassaye et al. Citation2006; WHO 2010). A good insight into the traditional system of medicine is essential, especially in a country where people cannot afford the drug-oriented systems of modern healthcare (Gari et al. Citation2015).

The application of good manufacturing practices (GMP) in the manufacture of herbal medicines is an essential tool to ensure their quality. The qualification and cleaning of critical equipment, process validation, and quality control are particularly important in the production of herbal medicines. There should be dedication to and avoidance of direct contact with chemicals to use traditional equipment such as wooden implements, pallets, hoppers, and clay pots. According to the American Herbal Products Association (AHPA Citation2017), if their use is unavoidable, after use, the equipment should be appropriately cleaned and sanitized to prevent cross-contamination (WHO Citation2007; AHPA Citation2017). Therefore, this study assesses THs’ knowledge and utilization of PE and MSs in the Amhara region, North West Ethiopia.

Materials and methods

Study design and period

A cross-sectional study design was conducted from June 1, 2022 to July 15, 2022.

Study area

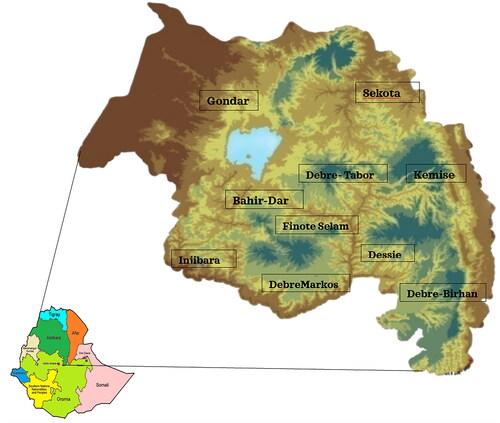

This study was conducted in the Amhara region, North West Ethiopia. Based on the 2007 census conducted by the Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia, the Amhara region has a population of 17,221,976 with 1.7 annual growth rates, of which 8,641,580 were men and 8,580,396 were women (Meseret Citation2016). According to Ethiopian Food and Drug Administration data, 422 registered THs have been found in the Amhara region.

Source and study population

All THs in the Amhara region were the basis of the study. However, the final study participants were THs who fulfilled the inclusion criteria of the study.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

THs who were registered and practiced their work for more than one year were included in our study. Those who did not volunteer to participate in the study were excluded.

Sample size and sampling techniques

We considered THs working area as a health care facility. When resource restriction is a concern in studies, the Logistic Indicator Assessment tool (LIAT) (USAID| DELIVER) advised a minimum of 15% of healthcare facilities be considered to evaluate the facilities in a specific area. Based on this recommendation, 15% of the THs’ facilities found in the Amhara region were included. The sample size was determined as follows:

where: n = the required sample sizeN = Total number of THs facilities in the region which were 422n = 422*0.15 = 63.3, when we use a non-response rate of 10%, the sample size equals 69.9. The final sample size included 70 TH facilities. A systematic random sampling technique was used to select these 70 TH facilities. At each of the 70 TH facilities, one TH professional was employed.

Study variables

The dependent variables of the study were knowledge and utilization of PE and MSs by THs. The independent variables were socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents (gender, age, religion, marital status, educational status, and years of experience).

Data collection instrument and procedure

Data were collected using interview-based questionnaires adapted from previous literature. The items were used by international organizations, national studies such as the demographic and health survey, and published articles in peer-reviewed journals in the working area of THs (WHO Citation2008; Ragunathan et al. Citation2009; Wassie et al. Citation2015; Alemayehu et al. Citation2016; WHO Citation2016; Hasen and Hashim Citation2021; Eigenschink et al. Citation2023). The questionnaire consists of a list of items that evaluate THs’ knowledge and utilization of PE and MSs. Data collectors distributed the Amharic-language questionnaires to all selected THs in the study area after briefly explaining its purpose. We used a three-point Likert scale (1 = Always; 2 = Sometimes; 3 = Never) to assess the utilization of PE and MSs by THs. A total of three pharmacists with previous experience in data collection were recruited for data collection. To reduce any potential research bias during the study, the data were collected in in-person interviews at the working area of the THs.

Data quality control

The questionnaire was first prepared in English, translated into Amharic, and retranslated back into English to check the originality of the message. For face validation, the questionnaire was sent to academics and subject-matter experts; after their input, the questionnaire was simplified and made to be more objectively focused. A pretest was done with 10 respondents out of the study area (at Addis Ababa). Based on the pretest, a few amendments were integrated into the final version questionnaires. Half-day training was provided to the data collectors to brief the objective, and relevance of the study, and how to collect the data using face-to-face interviews. Finally, data were collected with a daily checkup by the principal investigator for completeness and quality.

Operational definition of terms

Traditional medicines are the health knowledge, beliefs, approaches, and practices of incorporating various natural-based medicines with manual techniques and spiritual therapies to prevent, diagnose, and treat illnesses (Marques et al. Citation2021).

Traditional pharmacy compounding was defined by the Food and Drug Administration as mixing, combining, or altering ingredients to make a suitable medication for an individual patient in response to a prescription (Galson Citation2003). It was also defined by United States Pharmacopeia (USP) as combining, admixing, diluting, pooling, reconstituting, or altering a drug or bulk drug substance to make a non-sterile medication (USP30/NF335 2015).

Medical supplies are goods that are disposed of after treating a patient, including needles, syringes, bandages, suture materials, filters, and surgical and examination gloves (USAID/BHA Citation2010; USP30/NF335 2015).

Pharmaceutical equipment are instruments that are used for the preparation of medicines, which should be designed, constructed, and maintained as required by the operations to be carried out in the local environment. PE includes a balance, microscope, and mortar with a pestle, beakers, graduating cylinders, spatulas, and ointment tiles (WHO 2010).

Data processing and analysis

Data were checked, cleared, and entered into Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 25.0 software for analysis. The results were provided using basic frequencies with percentages, and mean with a standard deviation (SD) in the appropriate tables. The presence or absence of association between socio-demographic factors and THs’ knowledge of PE and MSs was determined using Pearson’s Chi-squares test with a statistically significant level of 0.05.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents

A total of 70 respondents were included (), with a response rate of 85.7%. Among the respondents, 58 (96.7%) of them were males, making up the majority. The mean age of the respondents was 46.43 years with a SD of 9.19. About 50% of respondents were illiterate (not taking formal education), 10.5% had completed primary and secondary educational levels, and the remaining (23.3%) had completed tertiary education. The mean experience of the respondents was 21.23 years with a SD of 9.29. None of the socio-demographic factors had a significant association with THs’ knowledge of PE and MSs ().

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents (n = 60).

Traditional healers’ knowledge and usage of pharmaceutical equipment and medical supplies

Most THs (90%) had some awareness of at least one of the PE and MSs. In addition, 12 (20%) of them had information about needles, gloves, and syringes; 8 (13.3%) of them had heard about most PE and MSs, such as mortars and pestles, beakers, needles, gloves, tiles and spatulas, graduating cylinders, syringes, thermometers, and milling machines ().

Table 2. Traditional healers’ knowledge about pharmaceutical equipment and medical supplies (n = 60).

We found that 48 THs (80%) used various equipment and supplies, both separately and in combination. The most used items by THs were needles, gloves, and syringes. The set of ‘mortar and pestle, needle, syringe, and milling machine’ and ‘beaker, needle, glove, graduating cylinder, and syringe’ each were used by 6.7% of THs, respectively ().

Table 3. History of using pharmaceutical equipment and medical supplies by traditional healers (n = 60).

The history of equipment and supplies usage was parallel to the current usage. 12 (20%) of them had used needles, gloves, and syringes starting from the previous up to now, and 4 (6.7%) of them had used mortars and pestles, beakers, needles, gloves, tiles, spatulas, graduating cylinders, syringes, thermometers, and milling machines ().

Table 4. Current usage status of pharmaceutical equipment and medical supplies by traditional healers (n = 60).

Traditional healers’ sources of knowledge about traditional treatments, pharmaceutical equipment, and medical supplies use

The majority of THs (53.3%) learned about the use of TMs, PE, and MSs through their families. Moreover, 10% of them gained their knowledge from religious schools, and 6.7% did so through a combination use of pharmacy advice, television, family, and religious schools. The majority of THs (80%) also had information on accessing areas of PE and MSs. Only 46.7% of THs received training ().

Table 5. Way of learning about traditional treatment, pharmaceutical equipment and medical supplies (n = 60).

Traditional healers purchase characteristics of pharmaceutical equipment and medical supplies

About 36 (60%) of the THs purchased their equipment and supplies mostly from supermarkets and 6 (10%) from wholesalers. Only two (3.3%) of the THs received their equipment and supplies from a variety of sources, including wholesalers, the Pharmaceutical Fund and Supply Agency (PFSA), supermarkets, and donations. A donation was mainly gained from health facilities and community pharmacies. The majority of THs (53.3%) made monthly PE and MSs purchases. Additionally, 46.7% of them spend less than 1000 Ethiopian birr each month because they recycle the majority of their equipment and supplies. About 11.7% of THs described that their preference for self-prepared equipment was the main justification for not employing PE and MSs. One TH also admitted that he hadn’t previously used PE and MSs because he thought his TMs would become ineffective when exposed to contemporary technologies ().

Table 6. Purchasing area, purchasing frequency, spent for purchasing, and reason for not purchasing by traditional healers (n = 60).

Traditional healers’ practices regarding pharmaceutical equipment and medical supplies

Usage and maintenance of pharmaceutical equipment and medical supplies

In the current study, 66.7% of THs use PE and MSs intermittently and only 13.3% use them routinely. About 33.3% of THs never check their equipment and 43.3% rarely check it. About 36.7% of THs have not used any cleaning agents and 26.7% have not cleaned their equipment. Only 15% of THs frequently maintain their equipment and 13.3% consistently use cleaning agents ().

Table 7. Traditional healers’ practices towards pharmaceutical equipment and medical supplies use (n = 60).

Training and experience sharing

Most THs (63.3%) do not interact with other healers and refuse to do so. The majority of THs (53.3%) have not had any training from pharmacy experts or other stakeholders ().

General equipment used by traditional healers

About 23% of THs used a combination of PE, medical equipment, stone, wood-prepared materials, cooking items, and kitchen equipment. About 20% and 16.7% of THs used cooking materials and wood-prepared materials respectively. Only 10% of THs exclusively used PE alone ().

Table 8. General equipment used by traditional healers (n = 60).

Discussion

Ethiopia has not yet adopted particular herbal medicines or TMs policies and laws to provide an independent regulatory system for good compounding and usage of THs medicines. One of the key challenges affecting the effective regulation of herbal products and TMs in Ethiopia is a lack of financial support for scientific research, as well as a lack of methods to monitor the safety of medicines (Demeke et al. Citation2022). These shortcomings are barriers to the creation or updating of national policies, laws, and regulations for TMs (WHO Citation2005).

Inadequate regulation in combination with inappropriate use of PE and MSs may worsen the irrational use of TMs. Improving the usage of PE and MSs by THs should be a regional and national strategy, as WHO strategies in Africa focus on safe, effective, and quality TM production and practices to promote therapeutically sound use of TMs providers and consumers (Fokunang et al. Citation2011). Manufacturing mainly depends on equipment performance, which is one of the determinants of GMP to ensure consistent quality production (Jain and Bharkatiya Citation2018).

This study showed that female practice in traditional treatment was low, which was approximately similar to Cameroon THs (90% of them were male), but in contrast with THs in rural South Africa (70% of them were females). Moreover, the educational status of our respondents was similar to Mali THs; most of them were illiterate, and only 10.5% had completed mandatory education (primary and secondary levels). However, this result was in the opposite of Cameroon THs, which showed 71% of them had a primary and high school education (Agbor and Naidoo Citation2011; Baratti-Mayer et al. Citation2019; Audet et al. Citation2020).

The results of knowledge and usage of PE and MSs were comparable, which showed that information was one of the determinant factors for the usage of PE and MSs. These results also explained the combined use of equipment and supplies by the THs.

Although most THs use various PE and MSs individually and in combination, most of them use traditional preparation equipment individually as well as in combination with modern equipment and supplies. About 23.3% of them had used wood-prepared materials, cooking materials, and stones in combination with PE and just 10% of THs used PE.

Most respondent THs gained knowledge of TMs, PE, and MSs usage from their family, which was similar to Cameron THs (most were trained by their family) (Agbor and Naidoo Citation2011) and Nepalese THs [they gained knowledge on traditional healing by training with a family member, i.e., grandfathers or fathers (52%) or with a traditional healer (48%)] (Pandey et al. Citation2023). In addition, it was comparable, but not the only way, to the study done in Ugand, which showed that knowledge of TMs accumulated over a long time is transmitted orally from generation to generation (Bagwana Citation2015). At this time, THs gained much emphasis from different stakeholders, including the University of Gondar. This University gave and planned continuous capacity-building training for THs. Despite the beginning of concern and work regarding THs, the training of THs regarding their compounding system in general and PE and MSs use specifically, were still low. However, this result was high relative to Cameroon’s training status: 71% of them had not received any formal training (Agbor and Naidoo Citation2011).

The practice of PE and MSs should be increased through continuous support and training of THs, as 80% of the population were TMs dependent due to several factors such as the cultural acceptability of healers and local pharmacopeias, the relatively low cost of TMs, and difficulty in accessing modern health facilities (Kassaye et al. Citation2006).

Cross-contamination occurs when the equipment is not properly cleaned before the preparation of another medicine (Lukulay Citation2016). In modern pharmacies, to remove residues from previous medicine preparations and environmental contamination, the cleaning procedure follows the standard operating procedure; each piece of equipment should be cleaned rigorously (Prioste et al. Citation2015). Factors related to efficient medicine include quality-related characteristics, environmental factors, personnel activities, and control processes, such as process monitoring and post-preparation control tests (Siamidi et al. Citation2017). GMP for TMs specifies many requirements for quality control of starting materials, including the correct identification of species of medicinal plants, special storage, and special sanitation methods for various materials (WHO Citation2005). Considering this, THs should receive appropriate training and should be controlled for the preparation and maintenance of quality products by ensuring their use of appropriate PE and MSs to make their treatment effective.

Limitations

Although this study has paramount importance in indicating further work in this area by, it has limitations. Such limitations include the small sample size and lack of comparison with other similar studies owing to the lack of data. The lack of articles related to PE and MSs made our comparison and discussion difficult. In addition, there was a lack of TH-related national guidelines, standard operating procedures, and policies that made our work strenuous in providing recommendations.

Conclusions

THs were aware of most PE and MSs, although there is still a gap in their use; their usage status was inconsistent and their desire to use equipment and supplies was moderate. This is mainly associated with their habit of using self-prepared and homemade equipment. Improving their knowledge and cooperation with other THs and modern health workers will increase their usage of PE and MSs, which serves to reduce inequalities and improve the standard of TMs compounding. As traditional treatment provides large patient care services regionally and nationally, great emphasis should be given to all stakeholders by focusing on improving their manufacturing and treatment strategies, by protecting them, and maintaining the quality of medicine. Additional scientific research is needed to explore and identify gaps related to equipment and supplies use, to help THs understand how to use PE and MSs, and to provide information about the potential risk associated with the inappropriate use of PE and MSs.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge all the THs who participated in our study; without whom this study would have not been conducted. We also thank all the individuals who collected our data and the authors of the references that we used.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aferu T, Mamenie Y, Mulugeta M, Feyisa D, Shafi M, Regassa T, Ejeta F, Hammeso WW. 2022. Attitude and practice toward traditional medicine among hypertensive patients on follow-up at Mizan–Tepi University Teaching Hospital, Southwest Ethiopia. SAGE Open Med. 10:20503121221083209. doi: 10.1177/20503121221083209.

- Agbor AM, Naidoo S. 2011. Knowledge and practice of traditional healers in oral health in the Bui Division, Cameroon. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 7(1):1–8.

- American Herbal Products Association (AHPA). 2017. Guidance: best TCHM Compounding and Dispensing Practices. American Herbal Products Association, Maryland.

- Alemayehu R, Ahmed K, Sada O. 2016. Assessment of knowledge and practice on infection prevention among healthcare workers at Dessie Referral Hospital, Amhara Region, South Wollo Zone, North East Ethiopia. J Commut Med Health Educ. 6:1–7.

- Al-Yahia OA, Al-Bedah AM, Al-Dossari DS, Salem SO, Qureshi NA. 2017. Prevalence and public knowledge, attitude and practice of traditional medicine in Al-Aziziah, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. BJMMR. 20(9):1–14. doi: 10.9734/BJMMR/2017/32749.

- Assefa D, Paulos G, Kebebe D, Alemu S, Reta W, Mulugeta T, Gashe F. 2022. Investigating the knowledge, perception, and practice of healthcare practitioners toward rational use of compounded medications and its contribution to antimicrobial resistance: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 22(1):243. doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-07649-4.

- Audet CM, Gobbo E, Sack DE, Clemens EM, Ngobeni S, Mkansi M, Aliyu MH, Wagner RG. 2020. Traditional healers use of personal protective equipment: a qualitative study in rural South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res. 20(1):655. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05515-9.

- Bagwana P. 2015. Indigenous knowledge of traditional medicine: answering the question of knowledge acquisition and transmission among the traditional health practitioners in Uganda. Antropoloji. (30), :13–32.

- Baratti-Mayer D, Baba DM, Gayet-Ageron A, Jeannot E, Pittet-Cuénod B. 2019. Sociodemographic characteristics of traditional healers and their knowledge of noma: a descriptive survey in three regions of Mali. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 16(22):4587. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16224587.

- Birhan W, Giday M, Teklehaymanot T. 2011. The contribution of traditional healers’ clinics to public health care system in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. J Ethnobiol Ethnomedicine. 7(1):1–7.

- Demeke H, Hasen G, Sosengo T, Siraj J, Tatiparthi R, Suleman S. 2022. Evaluation of policy governing herbal medicines regulation and its implementation in Ethiopia. J Multidiscip Healthc. 15:1383–1394. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S366166.

- Eigenschink M, Bellach L, Leonard S, Dablander TE, Maier J, Dablander F, Sitte HH. 2023. Cross-sectional survey and Bayesian network model analysis of traditional Chinese medicine in Austria: investigating public awareness, usage determinants and perception of scientific support. BMJ Open,. 13(3):e060644. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-060644.

- Fokunang, C N, Ndikum, V, Tabi, O Y, Jiofack, R B, Ngameni, B, Guedje, N M, Tembe-Fokunang, E A, Tomkins, P, Barkwan, S, Kechia, F, Asongalem, E,. 2011. Traditional medicine: past, present and future research and development prospects and integration in the National Health System of Cameroon.Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med, 3, 8: 284–295 doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v8i3.65276.

- Galson SK. 2003. Federal and state role in pharmacy compounding and reconstitution: exploring the right mix to protect patients. In a hearing before the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, 108th United States Congress (October 23, 2003) (hereinafter “Galson Statement”).

- Gari A, Yarlagadda R, Wolde-Mariam M. 2015. Knowledge, attitude, practice, and management of traditional medicine among people of Burka Jato Kebele, West Ethiopia. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 7(2):136–144. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.148782.

- Gudeman J, Jozwiakowski M, Chollet J, Randell M. 2013. Potential risks of pharmacy compounding. Drugs R D. 13(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s40268-013-0005-9.

- Hasen G, Hashim R. 2021. Current awareness of health professionals on the safety of herbal medicine and associated factors in the southwest of Ethiopia. J Multidiscip Healthc. 14:2001–2008. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S321765.

- Jain K, Bharkatiya M. 2018. Qualification of equipment: a systematic approach. Int J Pharm Erud. 8(1):7–11.

- Junsongduang A, Kasemwan W, Lumjoomjung S, Sabprachai W, Tanming W, Balslev H. 2020. Ethnomedicinal knowledge of traditional healers in Roi Et, Thailand. Plants. 9(9):1177. doi: 10.3390/plants9091177.

- Kassaye KD, Amberbir A, Getachew B, Mussema Y. 2006. A historical overview of traditional medicine practices and policy in Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 20:127–134.

- Lukulay P. 2016. Pharmaceutical manufacturing in LMICs: where things go wrong. In Quality Matters. Rockville, MD: the United States Pharmacopeial Convention (Vol. 24).

- Marques B, Freeman C, Carter L. 2021. Adapting traditional healing values and beliefs into therapeutic cultural environments for health and well-being. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 19(1):426. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19010426.

- McBane SE, Coon SA, Anderson KC, Bertch KE, Cox M, Kain C, LaRochelle J, Neumann DR, Philbrick AM. 2019. Rational and irrational use of nonsterile compounded medications. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2(2):189–197. doi: 10.1002/jac5.1093.

- Meseret D. 2016. Land degradation in Amhara Region of Ethiopia: review on extent, impacts and rehabilitation practices. J Environ Earth Sci. 6:120–130.

- Ofori-Asenso R, Agyeman AA. 2016. Irrational use of medicines summary of key concepts. Pharmacy. 4(4):35. doi: 10.3390/pharmacy4040035.

- Pandey DP, Subedi Pandey G, Sapkota S, Dangol DR, Devkota NR. 2023. Attitudes, knowledge, and practices of traditional snakebite healers in Nepal: implication for prevention and control of snakebite. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 117(3):219–228. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trac104.

- Prioste T, Magon TFDS, Fagundes V, Montanha MC, Moriwaki C, Kimura E. 2015. Recovery of drug residues in equipment and utensils used by compounding pharmacies after standard cleaning procedure. Braz J Pharm Sci. 51(2):317–322. doi: 10.1590/S1984-82502015000200008.

- Ragunathan M, Tadesse H, Tujuba R. 2009. A cross-sectional study on the perceptions and practices of modern and traditional health practitioners about traditional medicine in Dembia district, northwestern Ethiopia. Pharmacogn Mag. 6(21):19–25. doi: 10.4103/0973-1296.59962.

- Siamidi A, Pippa N, Demetzos C. 2017. Pharmaceutical compounding: recent advances, lessons learned and future perspectives. Glob Drugs Therap. 2(2):1–3. doi: 10.15761/GDT.1000115.

- United States Agency for International Development, Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (USAID/BHA). 2010. Emergency Application Guidelines Pharmaceutical & Medical Commodity Guidance. United States Agency for International Development/Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance, Washington, D.C.

- USP 30/NF 335. 2015. United States Pharmacopoeial Convention, Inc, Rockville, Maryland.

- Wassie SM, Aragie LL, Taye BW, Mekonnen LB. 2015. Knowledge, attitude, and utilization of traditional medicine among the communities of Merawi town, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2015:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2015/138073.

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2005. National policy on traditional medicine and regulation of herbal medicines: report of a WHO global survey. World Health Organization, Geneva.

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2007. Guidelines on good manufacturing practices for herbal medicines. World Health Organization, Geneva.

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2008. A guide to developing knowledge, attitude and practice surveys. World Health Organization, Geneva. Retrieved on May 15, 2022.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Good practices for pharmaceutical quality control laboratories. 2010. Technical Report Series, 957. World Health Organization, Geneva.

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2016. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practice surveys Zika virus disease and potential complications. World Health Organization, Geneva.