Abstract

The failure to adopt a South Atlantic Whale Sanctuary (SAWS) under the ambit of the International Whaling Commission (IWC) was twice caused by a deliberate breaking of the quorum by those members opposing the establishment of the SAWS. This situation has led the IWC to initiate the process of amending its Rules of Procedure (RoPs) to clarify whether the quorum is reached by simple attendance at the meeting or by being present in the room in which the session is held. This article provides some background on the issue at hand and analyses the RoPs of other bodies and meetings concerning the quorum. It then discusses the RoPs of the IWC and provides an analysis of the terms used in the document, after which the challenge of the quorum with regard to absentee voting is touched upon. Based on this discussion, this article provides further proposals for the amendment of the RoPs that, in the author’s view, would be beneficial for eradicating diverging interpretations.

1. Introduction

The question of whether or not an international organisation or any other decision-making body is factually and legally able to reach a decision is a question that has been little explored in the scholarly literature. Each organisation has its own Rules of Procedure (RoPs) that lay out the ways and procedures through which different meetings are to be held, who can attend the meeting, who can vote, and how decisions are to be reached. A crucial element in that regard is the capability of an organisation to be able to discuss and decide upon a specific topic, which is commonly known as the quorum.

In this article, I discuss the challenges of what constitutes the quorum at the International Whaling Commission (IWC). The relevance of this issue became ever more apparent at its 68th Meeting (IWC68) in Portorož, Slovenia, convened in October 2022. For the second time in its history, the IWC was facing a situation where several of its members, while present at the meeting, stayed away from a vote in order not to let the Commission be able to reach any decision. In other words, these member states purposefully broke the quorum by not being present in the room for the vote whilst being present at the meeting. Discussions consequently arose as to whether or not the quorum had already been reached when the members were present at the meeting but not present in the room for the vote. This begs a simple but significant question: Could the vote still have been conducted despite many members not being in the room? A final recommendation in this regard will be presented to the Commission at its next meeting in the fall of 2024 (IWC69).

2. Controversy at the IWC

The relevance of the quorum is particularly sensitive at the IWC, which has been characterised by controversy at least since the adoption of a zero-catch quota on commercial whaling in 1982, entering into force in the Antarctic whaling season 1985/86. This so-called ‘moratorium’ on commercial whaling meant that the Commission no longer permitted the killing of whales for commercial purposes by any of its members. While the moratorium was to be reviewed and possibly lifted in 1992, the necessary three-quarters majority to amend the Schedule—the operative part of the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (ICRW)Footnote1—has never been reached. In other words, the moratorium has remained in place ever since despite the Scientific Committee (SC) of the Commission itself having indicated that from a scientific perspective, commercial whaling of certain species is possible.Footnote2

While several members had lodged objections to the moratorium—which, according to Article V(3) of the ICRW, they are entitled to do—this has not prevented the Commission from experiencing a rift that has marked its operations up to this day. On the one hand, whaling nations such as Japan, Norway and Iceland have continued whaling activities with reference to the preamble of the Convention, which considers its object and purpose ‘to provide for the proper conservation of whale stocks and thus make possible the orderly development of the whaling industry’. On the other hand, anti-whaling nations consider the IWC to have moved direction towards the preservation of whales, therefore applying an evolutionary interpretation of the object and purpose of the Convention.Footnote3

Norway is one member that has lodged an objection that it has never withdrawn, and therefore openly continues to conduct commercial whaling. Japan had entered and subsquently withdrawn its objection, while Iceland also still conducts commercial whaling, albeit without an objection. The process as to why this is possible is fundamentally different, however. Japan withdrew its objection to the moratorium progressively under pressure from the United States, which threatened to close its domestic waters to Japanese fishing vessels, based on what is known as the Pelly Amendment to the Fishermen’s Protective Act of 1967.Footnote4 The Pelly Amendment allows for the imposition of trade barriers in regard to marine products if a country undermines a marine conservation initiative, of which the IWC is regarded. Under the sword of Damocles of being notified under the Pelly Amendment, Japan abandoned its commercial whaling programmes and shifted its focus on whaling operations as part of its ‘special whaling permit’ (scientific) whaling programmes in the North Pacific and in the Southern Ocean.Footnote5 Inevitably, this sparked controversy since Japan was accused of conducting ‘commercial whaling in disguise’ since the yield of these operations could be found as whale meat on the Japanese domestic market.Footnote6 Although Japan sought to gain a quota for its coastal whaling communities and therefore introduce a new category of whaling under the ICRWFootnote7—known as small-type coastal whaling—this attempt repeatedly failed, mainly because it was considered as simply a pseudonym for commercial whaling.Footnote8 As a result, Japan left the IWC effective from 30 June 2019, abandoned its special permit whaling in the Southern Ocean and started to engage again in commercial whaling within its own 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zone (EEZ).

The case of Iceland was different. While it never lodged an objection to the moratorium, it first engaged in rather small-scale special permit whaling in the late 1980s, but then in 1992 formed the North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO) along with Norway, the Faroe Islands and Greenland. Contrary to the IWC, NAMMCO explicitly focuses on the conservation and sustainable use of marine mammals in the North Atlantic. This led scholars and practitioners to consider them as competing entities concerning the regulation of whaling.Footnote9 While this has not turned out to be an issue and both the IWC and NAMMCO attend each other’s meetings as observers, Iceland decided to leave the IWC and to conduct commercial whaling under the ambit of NAMMCO. In 1992, Iceland’s withdrawal became effective.Footnote10

Not even 10 years later, however, Iceland filed an application to re-adhere to the Convention and thereby to re-join the Commission. While in principle this is a rather straightforward issue and there is no provision within the Convention that would deny a country membership, Iceland filed its application with the caveat of a reservation against the moratorium. After several years of controversy, Iceland was able to rejoin the IWC in 2002, including its reservation against the moratorium. In other words, Iceland can legally engage in commercial whaling under the ambit of the Commission.Footnote11

Apart from these matters of controversy, the Commission has been dogged by severe disagreements with delegates leaving the room because of differences in opinion,Footnote12 over vote-buying in order to push through certain decisions,Footnote13 and over intentional breaking of the quorum.Footnote14

3. The South Atlantic Whale Sanctuary—A Challenge for Quorum Rules and Good Governance?

The issue of the quorum had not arisen in the IWC prior to the 63rd meeting of the Commission in St Helier, Jersey (UK), in 2011. In principle, the same—or a very similar—situation occurred again at IWC68 in Portorož: the intentional breaking of the quorum by making use of unclear provisions concerning the quorum in the Rules of Procedure.

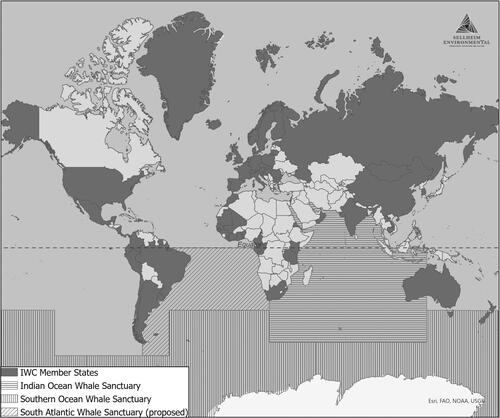

To provide context, however, it is necessary to outline the reason for breaking the quorum. At the core of controversy stands the proposed South Atlantic Whale Sanctuary (SAWS). The SAWS was first proposed in 1997 as the third whale sanctuary to be adopted under the auspices of the IWC after the Indian Ocean Whale Sanctuary in 1979 (which became permanent in 1992) and the Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary in 1994. Together with the proposed SAWS, significant swaths of the world’s oceans would be designated as whale sanctuaries in which specific requirements for the conservation of whales exist, notwithstanding a potential lifting of the moratorium (see map).

Adding the SAWS to the pre-existing designations of whale sanctuaries is at odds with the idea of the sustainable utilisation (i.e., lethal use) of cetaceans, for instance as a food source and based on commercial premises. To this end, it is also unsurprising that those countries that favour whaling, along with their supporters especially from the Caribbean and Africa, have thus far vehemently opposed the establishment of the SAWS since it was first put to a proper vote in 2011. Furthermore, the main reason for this opposition rests in the claim that the proposed sanctuary is not based on scientific grounds, and that it applies an equal conservation desigfnation to all cetaceans located within the SAWS area, although the different species and even different sub-populations each have different conservation statuses.

Although the SAWS had been discussed at Commission meetings on a rather regular basis since 2001, in 2011 at IWC63 the discussions reached a new climax when Brazil and Argentina presented the respective proposed Schedule amendment that would establish the SAWS. Since only five IWC members spoke against the proposal, with Russia calling on the proponents to withdraw it, and three members declining to join the consensus, the proponents called for the Commission to put the proposal to a vote, thus requiring three-quarters of the Commission members to be in favour in order for the Schedule to be amended.

In order to avoid defeat and for the SAWS to be adopted by the Commission, 21 countriesFootnote15 left the room and therefore broke quorum. The vote did therefore not materialise. According to the Commission’s Rules of Procedure, ‘attendance by a majority of the members of the Commission shall constitute a quorum’,Footnote16 which can hardly be considered a precise definition of what constitutes the Commission quorate. However, it was sufficient for the Chair to rule that the quorum was broken, since only 59 out of 89 Members of the Commission had attended the meeting, but with 21 members leaving the room only 37 members remained present—which constituted a minority.

As a consequence of the actions taken by the 21 SAWS-opposing states and since it was not factually clear whether the Commission could still be considered quorate, a Private Commissioners’ Meeting was called and an intersessional group was established to consider the interpretation of the Commission’s RoPs regarding the quorum. For IWC63, however, the SAWS was no longer considered as an agenda item and postponed to IWC64 one year later.Footnote17

At IWC64, the report of the intersessional group on the quorum was presented. The groups aimed to link the issue of the quorum to voting rights, especially concerning those countries in arrears. In other words, if a member does not have voting rights, it should consequently not be counted to the quorum. After a discussion that again failed to lead to a consensus and in which Japan argued that a suspension of voting rights cannot be equated to a suspension of membership—thereby breaking the RoPs if it was indeed tied to one another—the Commission’s chair decided to leave the RoPs unchanged, hoping that it would be possible ‘to handle the commission’s meetings without the need for further clarification on quorum’.Footnote18

Unfortunately, the Chair’s hopes did not come to fruition. While the issue did not arise again until 2022 (attributable also to the decision by the Commission from 2014 onwards to move its meeting schedule from annual to bi-annual), and even though the SAWS did play a role in the Commission’s deliberations, the unchanged RoPs caused yet another challenge. Following the discussions on the establishment of the SAWS, the issue was scheduled to be put to a vote after the lunch break. However, 16 membersFootnote19 decided to stay away from the session, therefore leading the Chair to conclude after a heated debate with those countries present that the Commission had not reached quorum. Ultimately, of the 88 members, only 42 countries remained in the room when the opponents to the motion did not attend—again constituting a minority.

During the discussions, two strains of argument were brought forth: One noted that ‘attendance’ meant that the quorum should be reached at each particular agenda item that is being put to a vote, meaning that ‘attendance’ essentially requires physical presence in the room for a particular vote. The other view noted that ‘attendance’ refers to the meeting as a whole, therefore not requiring more than 50% of the members to be present in the room at a particular vote, as long as more than 50% are attending the meeting overall. Not surprisingly, the latter interpretation was brought forth by the proponents and supporters of the SAWS who wished this issue to be adopted by the Commission. The alternative interpretation was applied by those states opposing the SAWS and staying away from the vote, along with the United States, who noted that decisions such as this should not be made by a minority group.Footnote20

The decision of the Chair not to follow the second interpretation, but to decide that the Commission had not reached a quorum, did not arise arbitrarily, but essentially mirrored the majority—yet not consensual—view on the issue of the quorum at IWC64. Here, an amendment to the RoPs was presented to the Commission. While it was supported by a majority, it was not adopted due to the lack of consensus. The amendment read:

The presence in the room by a majority of the members of the Commission shall constitute a quorum, which shall be required for any decision to be taken. The Chair will announce prior to each vote if a quorum is present. If participants choose to leave after the announcement, or do not participate in the vote, the quorum shall be considered to remain.Footnote21

4. The IWC’s Rule of Procedure

The IWC’s RoPs are not significantly different from the RoPs of other bodies and comprise 18 subsets of rules (Rules A–R) that are of relevance to the proper functioning of the Commission. Briefly summarised, they establish that each Party to the Convention is represented by a Commissioner and an Alternate Commissioner (or other alternate representation) at the bi-annual meetings. Apart from the Parties, rules for Observers are also established, which can be drawn from civil society (non-governmental organisations), intergovernmental organisations or governments that are not currently party to the Convention. The RoPs further lay out rules for proper accreditation, credentials and decision-making, the role of the Chair, Vice-Chair and Secretary, the role of the Chair of the Scientific Committee, the financial year and the location of the IWC’s offices (which are currently based in the UK).

The RoPs further stipulate the rules for the establishment of the Bureau—comprising the Chair and Vice-Chair of the Commission, the Chair of the Finance and Administration Committee, and four Commissioners who represent a wide range of views and reflects a regional balance. Generally, the mandate of the Bureau is to assist the Commission in its management processes. However, it merely serves as an advisory body and cannot make decisions on substantive matters. In disputes related to the quorum, the Bureau can therefore merely provide guidance.

The RoPs further set English as the official language of the Commission, with Spanish and French as additional working languages. This means in practice that at the meetings, English, Spanish and French interpretation will be provided. In the past, Japanese interpretation was also made available, but at the cost of Japan. Further, documents will be made available in English, French and Spanish. The rules for publication of documents related to the different meetings of the Commission are furthermore included in the RoPs, regarding the reports of the meetings, reports, communications and other Commission documents. Reports from committees, sub-committees and working groups are generally confidential until the opening of the plenary for which they have been prepared. Finally, the RoPs can be amended by simple majority vote.

Obviously, the question of the quorum strongly relates to the decision-making capability of the IWC—albeit only at the bi-annual Commission meeting itself. Intersessional decision-making has thus far not been confronted by challenges to the quorum. The most recent example is the vote concerning the new Executive Secretary Martha Rojas Urrego, the successor to Rebecca Lent, who left her post in September 2023. Concerning intersessional decision-making, the RoPs stipulate that ‘between meetings of the Commission or in the case of emergency, a vote of the Commissioners may be taken by post, or other means of communication in which case the necessary simple majority shall be of those Contracting Governments whose right has not been suspended under paragraph 2 casting an affirmative or negative vote, or where required, the necessary three-fourths majority, shall be of those Contracting Governments whose right to vote has not been suspended under paragraph 2 casting an affirmative or negative vote. In each case, a simple majority of the members of the Commission must have cast a vote’.Footnote22 This means that if only 44 members of the Commission have cast a vote, the vote is invalid. It therefore requires at least 45 members to cast a vote, setting the quorum at a simple majority. In the official communication confirming Urrego’s appointment, the Chair of the IWC, Amadou Télivel Diallo, merely noted that he was ‘pleased to confirm that the required number of votes has been achieved and therefore Martha’s appointment is formally endorsed’.Footnote23 The quorum for the vote was consequently reached and the IWC was capable of formally endorsing Urrego’s appointment.

5. The Quorum in International Organisations and Decision-Making Bodies

The Rules of Procedure of the International Whaling Commission do not constitute an unusual definition of the quorum. Several online legal dictionaries essentially provide a very similar, if not near-identical, definition of a quorum: the minimum number that must be present/must attend a meeting to enable to body to make decisions. Without a clearer definition of the quorum, which is referred to in the organisation’s RoPs (see below), it is common practice to approach the quorum through the lens of a simple majority. This is to say that a body is capable of making decisions when the majority, that is, 51%, of eligible members are present.Footnote24

The purpose of a quorum is twofold: First, it obviously serves the body to prevent decision-making by a minority, which would not be representative for the body. Second, a quorum allows for states to enter into abstentions to a vote without defeating the vote on the subject itself. In other words, by putting in place criteria for a quorum, broad participation in a vote is encouraged.Footnote25 It must be pointed out, however, that the purpose of the quorum necessary for decision-making is to encourage participation of those parties or stakeholders with voting rights. Consequently, in order to reach an as much representative vote as possible, a precondition is having voting rights. This consequently allows for the identification of two different quora: one for starting and engaging in the debates (quorum 1), and one for decision-making/voting (quorum 2).

Debates within a body can consequently also be taken up even though not all parties present in the room have voting rights. The purpose of quorum 1 is therefore to engage in debates with as many parties as possible and to reflect as many different views as possible, so that the body can reach a decision with the maximum number of viewpoints incorporated. While in theory this is rather clear, as we can see below, the term ‘quorum’ is mostly mentioned and defined for the start of the debates that ultimately lead to a vote. The vote itself is guided by its own rules, by its own quorum, even though it is not necessarily defined as such, as demonstrates.

Table 1.

While these rather broad definitions and purposes of a quorum prima facie appear to clarify the issue, the example from the IWC demonstrates that this is far from the truth. Indeed, as is shown below, different bodies have different rules in place that determine whether or not that body actually has decision-making powers. Some, like the International Astronomical Union (IAU), do not have quorum rules at all. When in 2006 the General Assembly of the IAU voted on a resolution that determined that Pluto was no longer to be considered a ‘planet’, but rather a ‘dwarf-planet’—thus reducing the number of planets of the Solar System from nine to eight—the vote was held at the end of the meeting when the majority of participants had already left. This meant that of approximately 10,000 members, less than 5% (i.e., less than 500) voted on the resolution, a vote that had significant impacts since history and science books now need to be rewritten. Not surprisingly, that particular vote has been faced with rather strong opposition, but still remains in place.Footnote26

For international organisations, four different types of quorum rules for quorum 1 could be identified: A quorum is reached when (i) the majority is present in the room; (ii) the majority is present at the meeting; or (iii) a minimum number is present for a vote and/or present for the body to conduct its business (i.e., different quora for votes and conduct of business). The fourth type refers to a lack of specification. At the same time, all bodies under scrutiny here have specific rules in place the guide their decision-making and the voting procedures. As shows, however, nine out of 14 instruments and bodies have voting rules in place (quorum 2) that do not mirror the rules for the debates to begin (quorum 1). And it is only five out of 14 instruments that more clearly define what the terminology ‘present and voting’ means. Only two instruments make clear that ‘present and voting’ refers to presence at the session at which voting takes place.

presents several international decision-making bodies and their respective provisions on the quorum, arranged in alphabetical order and based on their Rules of Procedure.Footnote27

What becomes clear from the survey of practice of these bodies is that the quorum does not enjoy the same definition across international organisations. That means that while organisations do have rules in place that ensure that a quorum is reached, this does not mean that it is clearly defined and shields the organisation from any disputes. Those organisations with an ‘unspecific’ quorum rule are especially prone to potential disputes concerning the decision of whether or not a quorum is reached, especially if:

Quorum 1 and quorum 2 are not in line with one another;

The quorum rules are not clearly defined; or

Quorum 2 is not considered as a quorum, but is treated differently to quorum 1.

That said, upon closer scrutiny of especially those bodies that were identified here as ‘unspecific’, an intentional breaking of the quorum (i.e., a ‘filibuster’ that intentionally delays the body from making any decisions) does not seem to have occurred in any organisation under scrutiny other than in the IWC. In fact, the issue of the quorum has hardly arisen in any other forum. Arguably, the reason for this is that none of these bodies is as politically divided as the International Whaling Commission and that, unlike the IWC, clear dispute settlement processes are in place, paired with a solution-oriented approach to policy- and decision-making. Even in highly politically divided entities such as the European Parliament, filibuster procedures are strictly controlled insofar as the speaking time of every Member of the European Parliament is limitedFootnote28—contrary to the United States Senate, for example.

In other legislative bodies, filibuster procedures are possible, but are very much in the hands of the chair of the meeting or house. In Germany, for instance, the German Parliament is considered capable of making decisions when more than 50% of its members are present.Footnote29 The practical application of this rule makes it look factually different, however: Since the Parliament also makes decisions in smaller groups and committees, the number of participants involved is often significantly smaller. Here it lies again in the hands of the Chair and the Board of the meeting to decide whether the Parliament has decision-making powers. This, in the end, also leads to situations in which decisions are made by less than one fifth of the members of the German Parliament, based on a simple majority.Footnote30

While theory and practice are rather clear in this regard, there are also ways and means to delay or challenge a vote. Through three different means, Parliament has wiggle room in this regard. The first means is the Parliamentary Committee on Elections, Immunity and Rules of Procedure, which has the mandate to assess the legitimacy of elections within the Parliament and, if necessary, to call for a repetition of the vote. A second, and politically usable, means refers to the so-called ‘mutton leap’ (German: Hammelsprung). The mutton leap has never been included in the Rules of Procedure but has been part and parcel of German Parliamentary votes since the Nineteenth century. A mutton leap occurs when the president of a session and the secretaries do not find consensus concerning the outcome of a vote or if the decision-making capabilities are challenged by a Parliamentary group in case it has not been explicitly confirmed by the Chair. If this is the case, all Parliamentarians leave the room and re-enter it again through two different doors marked with ‘yes’ and ‘no’ in order for a clear outcome to be generated.Footnote31

The mutton leap has also been used as a political tool. For instance, in 2019 the right-wing Alternative for Germany (Alternative für Deutschland, AfD) requested a mutton leap when the President of Germany aimed for a rapid signing of three different laws that the AfD did not approve of. Since the AfD did not consider the Parliament having reached a quorum, it used the tool of a mutton leap to undermine the signing. While the Chair of the meeting refused this request, the AfD took the matter to the German Supreme Court, which, however, ruled in the Chair’s favour.Footnote32 A third way to challenge and potentially alter the outcome of a vote is to request a vote by name and not merely by hand sign. This can occur when a Parliamentary fraction or at least 5% of the present Parliamentarians request a vote by name.Footnote33

The challenge, however, does not necessarily lie in how the quorum is defined, because when considering quorum 1, no decisions are taken that are reliant on a certain number of parties present, but reliant rather whether or not the body can actually start engaging in the debates that lead to a decision, as mentioned earlier. The controversy surrounding the SAWS consequently did not centre around quorum 1, because no one challenged the presence or absence of IWC members in the room for the debates. Instead, the controversy surrounded the vote, that is, quorum 2, and whether or not a presence in the room was required for that vote. While, as outlined above, many IWC members considered a physical presence at the meeting as a prerequisite for the quorum, this does not touch upon the question of whether having a presence in the room yet exercising the right not to vote or not participating in the vote has implications for the quorum.

6. Discussion

The mere existence of a quorum shows that it has been considered a prerequisite for proper decision-making in international as well as national bodies, as the example from the German Parliament demonstrates. The fact that all international organisations and conferences included in have provisions on the quorum in their respective RoPs in place shows that it is a practice that has been considered sensible for the conduct of a meeting in order to come to certain conclusions and to enable equitable voting.

6.1. Quorum and Voting

It is voting procedures in particular that make the existence of a quorum rather self-evident. If, say, merely 40% of membership is present at a meeting, of which half does not participate in/abstains from a vote (leaving merely 20% of the membership casting a yes/no vote), with an end result of 11% voting ‘yes’ and 9% voting ‘no’, the absence of a quorum rule would mean that the body has made a ‘yes’ decision based on merely 11% of its membership. This cannot be considered representative, even though it might of course be possible that it would still be the majority voting ‘yes’ if 100% of the members had cast a ‘yes’/’no’ vote. The aforementioned example from the IAU vividly demonstrates this problem.

Consequently, the issue of the quorum and the issue of voting are very closely intertwined. For instance, the Rules of Procedure for the meetings of the six Committees of the UN General Assembly were amended in 1949 to link the ‘presence of a majority of the members of the committee’ to be ‘required for a question to be put to the vote’.Footnote34 In other words, the majority is required for any vote to be taken, with these revisions being silent on issues related to other decisions, for instance, those that are taken by consensus. The current version of the RoPs of the committees, however, has done away with this link and now reads, in line with the quorum provisions for the Plenary meetings: ‘The presence of a majority of the members shall be required for any decision to be taken’.Footnote35 When this change occurred cannot be ascertained.

The RoPs of the Ramsar ConventionFootnote36 reflect the status quo of the 1949 approach to the quorum and decisions in so far as they make it a requirement for any debate to continue when at least one third of the Contracting Parties are present and any decision to be taken by at least two thirds who are ‘present and voting’.Footnote37 In other words, sticking strictly to the text, consensus-based decisions appear not to be affected by the quorum requirements since a vote is not cast. In practice, this does not seem to be the case since consensus-based decision-making is a crucial element of the way in which the Conference of the Parties takes its decisions, as reflected in the reports of the Conferences of the Parties.Footnote38

The CMSFootnote39 is an even more confusing case in point: While the RoPs require that a quorum ‘consist of one-half of the Parties having delegations at the meeting’ (see ), the Convention itself does not help in clarifying the issue of the quorum or the validity of a vote. Article I(3) reads, ‘Where this Convention provides for a decision to be taken by either a two-thirds majority or a unanimous decision of “the Parties present and voting” this shall mean “the Parties present and casting an affirmative or negative vote”. Those abstaining from voting shall not be counted amongst “the Parties present and voting” in determining the majority’. What this means is that the two different quora have been considered from the outset: first, one third for the debates to begin and to call for a vote; second, at least half of the present countries present in the room casting an affirmative or negative vote. In order for the conference of the parties (CoP) to make a vote-based decision, therefore, both quora must be fulfilled. Whether this has ever been an issue in practice cannot be ascertained. That said, the reports of the CoPs do not reflect that this has ever seemed to have played a role in the deliberations.Footnote40

As can be seen in , the majority of instruments/meetings under scrutiny here are located in the category ‘(iii) different quora.’ This approach follows the practice of the United Nations, which has incorporated the lowering of the quorum at the beginning of a meeting in order to stimulate the discussions at an early stage of the meeting. As the Report of the Special Committee on the Rationalization of the Procedures and Organization of the General Assembly notes: ‘very often, presiding officers could not open meetings because of the lack of a quorum. If the present quorum requirements in Rule 69 and 110 were to be reduced, except with regard to voting, there would be an appreciable saving of time and the efficiency of the General Assembly would be considerably increased’.Footnote41

From a practical perspective, this approach is sensible since not all delegates may have arrived or credentials may not yet have been formalised. The higher level of the quorum when the issue is decided upon relates to the later stages of these decisions during the meetings. By then, presence and credentials are fully established and the vote/decision itself is more indicative of the opinion of the actual membership of the instrument/meeting.Footnote42

6.2. ‘Presence’

An evaluation of the RoPs in reveals that the declaration of a quorum or its ability to be reached hinges on the ‘presence’ of a certain number of Contracting Parties or representatives. While some RoPs are clear in regard to what ‘presence’ means—for instance, ‘presence’ during a session or ‘presence’ at a meeting—others are not. For instance, the Stockholm Convention and the United Nations Conventions cited here do draw a distinction between ‘presence’ at the beginning of the meeting and ‘presence’ for a vote. Neither clarifies, however, whether this means the physical presence in the room during the vote or indeed presence at the meeting (in the sense of being fully accredited and present at the venue). In the case of the IWC, ‘presence’ is substituted by the term ‘attendance’, which, for the sake of argument in this context, can be used interchangeably, but which is discussed in more detail below.Footnote43

The Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries define ‘presence’ of a person as ‘the fact of being in a particular place’.Footnote44 This implies that it would require an additional determinant to link this presence to a particular locale, such as a meeting room or a session. While some RoPs do this, as noted above, others do not. Despite this absence of the determinant, a contextual reading of the RoPs may prove helpful in this regard. Of particular interest are those RoPs that differentiate between a quorum for the opening of a meeting and the associated starting of the debate, and the quorum for votes. In both contexts, a minimum number of Parties is to be ‘present’. While this is not further defined, a debate cannot start if by ‘present’ mere presence at the meeting is referred to vis-à-vis presence in the room. While indeed the Party may attend the meeting by being physically at the venue, registered and accredited, the Party may not be participating in the session itself in which the debate is to take place. The Party is consequently not ‘present’ at the beginning of the meeting and therefore unable to contribute to the debate. This allows for the conclusion that in such a case a quorum is not reached and that ‘presence’ indeed refers to the physical presence in the room.

The case of CITESFootnote45 is somewhat more complicated. Here, the RoPs note: ‘[a] quorum for a plenary session of the meeting or for a session of Committee I or II shall consist of one-half of the Parties having delegations at the meeting’.Footnote46 While this may prima facie place the quorum as referring to the ‘presence’ at the CITES meeting and not as being in the room, observed practice of the Chairs at the different Committees as well as at the plenary session locates the definition of ‘presence’ as being present in the room in which the session takes place. As the meeting reports reflect, on one occasion a session of Committee II constituting the eighth session of the committee was not considered quorate and therefore a roll call vote was not possible. The session was suspended for nine minutes as a consequence.Footnote47 This implies that even though the delegates were already present at the meeting and fully accredited—after all, this was the eighth session of the meeting and the issue of the quorum did not occur before—the quorum as interpreted by the Chair meant the physical presence in the room in which the session was to take place. The CITES RoPs concerning voting do not clarify the issue of ‘presence’ since ‘present and voting’ merely refers to the status of accreditation and as such does not allow for an interpretation of the term ‘present’. Only the practice of the chair to consider the different committees quorate allows for a modus operandi in interpreting the rules.

6.3 ‘Attendance’ or ‘Participation’ at the IWC?

The terminology used in the RoPs of the IWC differs from that of other organisations and meetings insofar as it does not make use of the term ‘presence’ as a prerequisite for a quorum. Instead, “attendance by a majority of the members of the Commission shall constitute a quorum.”Footnote48 The Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries defines the term ‘attendance’ in a twofold manner: first (#1), ‘the act of being present at a place, for example at school’; second (#2), ‘the number of people present at an organized event’.Footnote49 While this might imply that the quorum refers to mere attendance at the meeting, the explanatory sentences that follow these definitions shed more light on the nature of this attendance. For the first definition, the two sentences read as follows:

‘Attendance at these lectures is not compulsory’.

‘Teachers must keep a record of students’ attendances’.

For the second definition, the sentences are:

‘There was an attendance of 42 at the meeting’.

‘Cinema attendances have risen again recently’.

Concerning #1, what becomes clear is that the term does not merely refer to the attendance at school of which the teachers must keep records, but that it refers to the physical presence in the room/at the lecture that define whether or not a student is in attendance. Concerning #2, a reading of the explanatory sentences allows for the conclusion that 42 people were present in the room in which the meeting took place for (most of) the duration of the meeting and that people attending the cinema does not merely refer to people being present at the compounds of the cinema, but that an increasing number of individuals bought cinema tickets and were inside the screening room in which the movie was shown. If, therefore, the term ‘attendance’ in the RoPs of the IWC were to be read as merely being present at the meeting but not inside the meeting room, this would furthermore break with the practice of the United Nations, as outlined above.

A further clarification of the issue could specify the term by adding the verb ‘to be’ before. This would formalise the definition in so far as this would imply a physical presence at a special event. The Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries exemplifies this in the following manner: ‘Several heads of state were in attendance at the funeral’.Footnote50 This means that several heads of state shared the same locale at a specific funeral with family members and others. The logical result of this is a recommendation for an amended rule that would not refer to ‘presence’ at the meeting or in the session, but rather to the used term ‘attendance’: A majority of the members of the Commission being in attendance shall constitute a quorum.

What makes matters significantly more complex is the fact that the RoPs of the IWC include a second term, which is closely linked to ‘attendance’: ‘participation’. The Commissioner from Argentina rightfully pointed to the fact that ‘the concept of “Attendance” is used in several provisions of the Rules of Procedure, among them in Rule D.1.(a) in which it specifically refers to “participation and/or attendance at each meeting”, which makes clear that these are different concepts’.Footnote51 Indeed, the RoPs read in Rule D.1.(a):

1.(a) The names of all representatives of member and non-member governments and observer organisations to any meeting of the Commission or committees, as specified in the Rules of Procedure of the Commission, Technical and Scientific Committees, shall be notified to the Secretary in writing before their participation and/or attendance at each meeting.Footnote52

‘A show with lots of audience participation.’

‘Participation in something A back injury prevented active participation in any sports for a while’.Footnote53

While at first glance ‘attendance’ and ‘participation’ appear to be very closely related, upon scrutiny of the ‘Extra Examples’ that the dictionary provides,Footnote54 it becomes clear that the term ‘participation’ appears to be somewhat more abstract than the term ‘attendance’. For example, it is possible to participate in a meeting without being physically present, for instance, by registering and accrediting, but not attending the sessions. In principle, participation has therefore occurred. At the same time, it is also possible to attend a meeting but not participate in the session. The abstract nature of the term ‘participation’ becomes ever clearer since the term ‘participate’ does not automatically specify an active participation. This means that it is possible to participate in a meeting without actively engaging in the discussions. This is not the same case with the term ‘attendance’: It is not possible to passively attend a meeting in which physical presence is required, whereas it is possible to passively participate in it.

6.4. Implications for Voting Procedures at the IWC

The question of how to interpret the RoPs with regard to the quorum has significant implications for the way in which voting and decision-making can be conducted in future. For instance, one matter that will be discussed at the IWC meeting in 2024 will refer to absentee voting rights. This means that IWC Members are able to cast a vote on a specific issue even though they are not physically present at the meeting. In other words, the term ‘attendance’ will become a crucial element in this discussion: How will ‘attendance’ be defined with regard to decision-making powers? Do those members physically attending have a different voting ‘weight’ than those not present? Will the doctrine of ‘one state, one vote’ for members of the Commission be upheld even though states are not physically attending the meeting (but may be virtually or sporadically)?

These questions cannot be answered at this point, but the IWC already has rules in place that weaken the ‘one state, one vote’ doctrine as far as those IWC members that are in arrears are concerned. As the RoPs stress in Rule E.2.(a), ‘The right to vote of representatives of any Contracting Government shall be suspended automatically when the annual payment of a Contracting Government including any interest due has not been received by the Commission by the earliest of these dates: […]’.Footnote55

In practice this means that full members of the IWC being present in the room of the meeting when a decision is to be taken do not have the right to vote on account of having failed to ensure payment of the annual fee. While this does not seem to correspond to fair international practice, especially with regard to developing states, it has been applied in other multilateral bodies. For instance, in 2020 the CMS adopted a resolution that goes even further than merely denying voting rights: Members in arrears are even denied the right to hold office in any of the Convention’s bodies if they have been in arrears for three or more years. This move was generally perceived as being beneficial for the Convention and as a tool to increase its effectiveness.Footnote56

The issue of governments being in arrears was also raised in 2022 at IWC68 in 2022. While the RoPs are rather clear in this regard, the COVID-19 pandemic has nevertheless placed additional burdens on several developing country members, which has made it ever more difficult to pay their annual contributions. The effects would have been that for years to come they would not have had voting rights while at the same time contributing to a decision-making quorum in which they have no voice. Inevitably, this situation could challenge the representativeness of the decisions taken by the Commission. In order to counter this rather worrying trend, in a virtual meeting in 2021, the Commission tasked the Working Group on Operational Effectiveness (WGOE) with the development of options for the change of the RoPs to address this issue. At IWC68, three options for changes of the RoPs were presented,Footnote57 with one option ultimately approved by the Commission. This option considers the Commission is capable of restoring voting rights in case of ‘exceptional circumstances,’ which resulted in those governments in arrears for the Plenary of IWC68 having their voting rights restored since the years 2020–2022 were considered ‘exceptional circumstances’ due to the pandemic.Footnote58

Be that as it may, ‘exceptional circumstances’ can also be used in a different manner and in relation to the participation in and attendance at a meeting: In a case in which a delegation is forced to leave a meeting because of a national emergency, because of precautionary measures (for instance an impending volcanic eruption that may threaten international air travel) or for any other reason, would this mean that (1) they do longer attend the meeting and therefore lose their participatory/voting rights? Furthemore, would a situation like this also mean that (2) the organisation potentially loses its quorum?

Concerning proposition (1), absentee voting rights would in all likelihood gain hold. If a member is properly registered, accredited and not in arrears (a status that is determined in whatever manner), there would be no reason to deny a member voting rights just because its delegates are not physically present (i.e., in attendance) at the meeting. In fact, not attending the meeting might even prevent the country from entering arrears by saving significant costs that would otherwise have been incurred for travelling and lodging for an extended period. However, in the absence of clear rules concerning absentee voting, amendments to the RoPs in this regard are necessary. In order to avoid minority decision-making just because fully accredited members are not present at the meeting, it is likely that this matter will be resolved at the next meeting.

That said, the notion of ‘absentee voting rights’ implies that a quorum is a prerequisite, because if no quorum was reached, voting would not be possible to begin with. The question on attendance/presence/absence of a meeting is of significance here. The current RoPs only marginally touch upon this issue in Rule E.1, which stipulates that ‘Each Commissioner shall have the right to vote at Plenary Meetings of the Commission and in his/her absence his/her deputy or alternate shall have such right’.Footnote59 In other words, just because the Commissioner is not present at the meeting does not mean that a country loses the right to vote or that this has any implications for the quorum. This does imply, however, that a member’s Commissioner was already present at the meeting, that s/he is no longer present in the room for the vote and that her/his alternate will make use of the right to vote in the Commissioner’s absence.

By interpreting the notion of ‘attendance’ as meaning ‘attendance at the meeting’ and not at the session, Rule E.1 could give rise to severe problems. If the Commissioner is not in the room for the vote (i.e., s/he is absent), but is still at the meeting (for instance, in a different room for a different meeting, in the bathroom, or elsewhere on the compound for any other reason), there would be no justification to allow her/his alternate to cast the vote since s/he would still be attending the meeting. Following this logic, the alternate would not be granted the right to vote while the quorum would still be considered to have been reached. To this end, the decision to be taken—either by vote or by consensus—would be occur without the voice of a fully accredited member of the Commission. This consequently underlines that it should be the physical presence in the room and not the attendance of the meeting that should be decisive for the reaching of the quorum.

Presence in the context of ‘absentee voting’ appears to be a conundrum: How can a member be ‘present’ and contribute to the quorum whilst being absent but eligible for the vote? Before briefly trying to untangle this matter, it is noteworthy that ‘absenteeism’ in this context does not necessarily mean that the absent country has a deeper political motivation not to attend the meeting, for instance, because of lack of interest,Footnote60 a lack of a clear policy-development in the respective home country, or in light of a weak ministry.Footnote61 Instead, countries in arrears or countries absent from the meetings are often developing countries that do not have the capacity (whether financial, political, or human) to attend the meetings, which take place in remote (or expensive) locations of the world. The idea to introduce mechanisms for absentee voting is therefore laudable in order to reduce costs and other challenges for developing countries and enable them to make full use of the ‘one state, one vote’ doctrine.

From a practical perspective, however, the issue is complex since the system would have implications on the quorum. The IWC would have to amend or specify its quorum rules so as to clearly define what ‘attendance’ means. The most obvious criterion would be that ‘attendance’ also implies participating in the sessions of the meeting via remote means such as Zoom, Teams or a similar platform. To some extent this process has already been initiated since the IWC has been streaming its meetings via its own YouTube channelFootnote62 since IWC66 in 2016. But although the meetings are therefore publicly viewable, viewers can still not ‘participate’ in the sessions given that there is only a chat function available and viewers are not considered officially registered and accredited observers to the Commission. This means that they do not have the right to speak (or potentially have their chat messages read out) before the Commission.

The challenge therefore lies in the reconciliation of being physically absent from the meeting, participating in the sessions of the meeting remotely, and being entitled to cast a vote. A quorum can only be established if the absent members of the Commission are counted as being present in the session through a means other than YouTube. A specific software designed for conferences that contains individual links with special permissions for absent members must therefore be created. While this generates costs as well, these must be regarded as significantly lower than those that would be incurred through travelling and lodging. Through these links, a quorum can be established once the delegates are able to join online.Footnote63 Consensus-based decision-making can therefore rather easily be established.

If a decision is taken by vote, absentee voting can occur through a mechanism within the software that either includes a yes/no/abstain option or simply enables the absent voter to show her/his support/opposition/abstention by a means that has been previously specified by the Secretariat. Since the IWC does not have the possibility for secret ballots, absentee voting would not be affected by this issue.

7. Proposed Changes to the Rules of Procedure

The preceding discussion has shown that the matter of the quorum and the accommodation of absentee voting requires some changes to the IWC’s Rules of Procedure for future meetings to be conducted without further challenges in this regard. In order to stimulate discussion, I therefore propose to the WGOE and to the Commission that they consider the following changes to the Rules of Procedure, where text in italics and strikethrough is deleted text and bold text shows proposed amendments:

Rule B.1:

Attendance by a A majority of the members of the Commission being in attendance shall constitute a quorum. Upon prior notification of the Secretariat, members are entitled to attend the meeting virtually by means established by the Secretariat. Special Meetings of the Commission may be called at the direction of the Chair after consultation with the Contracting Governments and Commissioners.

Rule D.1.(a):

The names of all representatives of member and non-member governments and observer organisations to any meeting of the Commission or committees, as specified in the Rules of Procedure of the Commission, Technical and Scientific Committees, shall be notified to the Secretary in writing before their participation and/or being in attendance at each meeting.

Rule E.1:

Each Commissioner shall have the right to vote at Plenary Meetings of the Commission and in his/her absence his/her deputy or alternate shall have such right. Commissioners or their deputies or alternates being in attendance remotely may also exercise their right to vote by means established by the Secretariat.

Rule E.2.(d):

Votes shall be taken by show of hands, by means established by the Secretariat for representatives being in attendance remotely, or by roll call, as in the opinion of the Chair, appears to be most suitable.

Rule E.3.(a):

3. (a) Where a vote is taken on any matter before the Commission, a simple majority of those participating in the session at which the voting takes place and casting an affirmative or negative vote shall be decisive, except that a three-fourths majority of those participating in the session at which the voting takes place and casting an affirmative or negative vote shall be required for action in pursuance of Article V of the Convention.

8. Summary and Conclusion

The controversies that have surrounded the decisions and decision-making of the International Whaling Commission have led the organisation to become rather prominent in scholarly discourse on international organisations. While with Japan’s exit in 2019 a major player advocating commercial whaling has left the organisation, controversy still persists. As the preceding has outlined, one crucial element lies in the unclear language of the IWC’s Rules of Procedure as regards the meaning of the word ‘attendance’.

Although also other organisations and meetings may also have RoPs in place that are not clear in their wording either, they are not as synonymous with controversy as the IWC. Therefore, the issue of the quorum has not surfaced prominently in these bodies. In the case of the IWC, however, questions surrounding the interpretation of the RoPs concerning the quorum surfaced already in 2011, but the problem was postponed in the hope that this might not occur again. In 2022, members opposing the establishment of the SAWS made use of this ambiguity again by purposefully breaking quorum prior to the vote on the proposed sanctuary, which consequently could not be adopted. To do away with these ambiguities once and for all, the next IWC meeting in 2024 is to address this as the first matter of business.

Essentially, two strains of argument prevail in the debate: First, ‘attendance’ and associated quorum relate to the attendance of the meeting and not of the session; second, ‘attendance’ refers to the physical presence in the room when a decision is to be made. While other organisations also refer to the meeting and not to the session as being a prerequisite for reaching a quorum, practice has shown that it is after all the number of members being present in the room when the quorum is being determined.

Throughout this article, I have argued that from a linguistic perspective also, based on the terminology used in the IWC’s RoPs, ‘attendance’ rather refers to the presence in the room of a session than to the presence at the venue/meeting. The matter becomes even more complex when rules for absentee voting are to be established, as intended by the IWC at its next meeting. Here, virtual attendance is a prerequisite for reaching a quorum, underlining again that attendance equates to active or factual participation in the session itself.

Based on the arguments laid out throughout this article, I have proposed changes to the Rules of Procedure that I invite the IWC and the Working Group on Operational Effectiveness (WGOE) to take into account in their deliberations. Without a solution to the challenges surrounding the quorum that is acceptable for all, the IWC has the potential to generate even more controversy that may weaken its operational effectiveness.

Notes

1 International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (ICRW) (adopted 2 December 1946, entered into force 10 November 1948) 161 UNTS 72.

2 IWC, ‘The Revised Management Procedure’, https://iwc.int/management-and-conservation/rmp.

3 On the interpretation of the ICRW, see M Fitzmaurice, ‘The Whaling Convention and Thorny Issues of Interpretation’ in M Fitzmaurice and D Tamada (eds), Whaling in the Antarctic: The Significance and Implications of the ICJ Judgment (Leiden/Boston, Brill, 2016) 53–138.

4 22 U.S.C. § 1978(a)(2).

5 N Sellheim, International Marine Mammal Law (Heidelberg, Springer, 2020) 109–111.

6 See, for example, Jonathan Iversen, An Angry Rift in the Year 2000: Japan’s Scientific Whaling’ (2001) 12 Colorado Journal of International Environmental Law and Policy 121.

7 The ICRW recognises three types of whaling: commercial whaling, special permit whaling, and aboriginal subsistence whaling (ASW).

8 S Fisher, ‘Japanese Small Type Coastal Whaling’ (2016) 3 Frontiers in Marine Science 121.

9 For example, TS Illingworth, ‘The North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO) vs. the International Whaling Commission: Who Can Legitimately Regulate Whaling?’ (1999) 3 Eco-Notes 1.

10 A Gillespie, ‘Iceland’s Reservation at the International Whaling Commission’ (2003) 14 European Journal of International Law 977.

11 E Couzens, ‘“Opening Up a Procedure”: Might the Re-adherence of Iceland to the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling in 2002 Provide an Example for Japan to follow?’ in N Sellheim and J Morishita (eds), Japan’s Withdrawal from International Whaling Regulation (Abingdon, Routledge, in press).

12 See for example IWC, Annual Report of the International Whaling Commission 2003 (Cambridge, IWC, 2004) 97.

13 JR Strand and JP Tuman, ‘Foreign Aid and Voting Behavior in an International Organization: The Case of Japan and the International Whaling Commission’ (2012) 8 Foreign Policy Analysis 409.

14 C Perry, ‘Blogging Live from the IWC: July 2011’, https://eia-international.org/blog/blog-iwc-fin-whale-updates. See also IWC, Annual Report of the International Whaling Commission 2011 (Cambridge, IWC, 2012) 24.

15 Japan, Cambodia, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, The Gambia, Ghana, Iceland, Norway, Nauru, Mongolia, Mauritania, Guinea-Bissau, Grenada, Kiribati, Morocco, Republic of Korea, Palau, Togo, Tuvalu, St Kitts and Nevis, and St Lucia.

16 IWC, Rules of Procedure and Financial Regulations (Cambridge, IWC, 2022) Rule B.1.

17 IWC, Annual Report of the International Whaling Commission 2011 (Cambridge, IWC, 2012)

18 IWC, Annual Report of the International Whaling Commission 2012 (Cambridge, IWC, 2013) 60.

19 Antigua and Barbuda, Benin, Cambodia, Côte D’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, Iceland, Kiribati, Laos, Liberia, Mauritania, Morocco, Nauru, Palau, St Lucia and the Solomon Islands.

20 IWC, Chair’s Report of the 68th Meeting of the International Whaling Commission (Cambridge, IWC, 2022) 23.

21 IWC (n20) 122.

22 IWC (n14), Rule E.4.

23 IWC, ‘Martha Rojas-Urrego, Confirmation of Appointment as IWC Executive Secretary’, 4 August 2023, https://archive.iwc.int/pages/download.php?direct=1&noattach=true&ref=20360&ext=pdf&k=.

24 C Wang, ‘Issues on Consensus and Quorum at International Conferences’ (2010) 9 Chinese Journal of International Law 717.

25 L Randolph, The Fundamental Laws of Governmental Organization (New Haven, College & University Press, 1971) 49.

26 Paul Rincon, ‘Pluto Vote ‘Hijacked’ in Revolt’ BBC News, 25 August 2006, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/5283956.stm.

27 The various RoPs are reproduced in full here: Cartagena Convention: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/32680/UNEP, 2010-Rules of Procedures-en.pdf?sequence = 1&isAllowed = y; CBD: https://www.cbd.int/convention/rules.shtml; CITES: https://cites.org/sites/default/files/eng/cop/E16-Rules.pdf; CMS: https://www.cms.int/sites/default/files/document/COP11_Doc_04_Rules_of_Procedure_E.pdf>; European Council: https://www.cvce.eu/content/publication/2014/11/5/00df8091-d7e0-4740-8867-ff0175fb6eb0/publishable_en.pdf; European Parliament: <https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/RULES-9-2023-07-10-TOC_EN.html; ICC: https://asp.icc-cpi.int/sites/asp/files/asp_docs/ASP7/ICC-ASP-Rules_of_Procedure_English.pdf; IWC: https://archive.iwc.int/pages/download.php?direct=1&noattach=true&ref=3605&ext=pdf&k=; Ramsar: https://www.ramsar.org/sites/default/files/documents/library/ramsar_rules_of_procedure_e.pdf; Stockholm: https://www.basel.int/Portals/4/download.aspx?d=UNEP-FAO-CHW-RC-POPS-PUB-COP-RulesOfProcedures.English.pdf; UNCCD: https://knowledge.unccd.int/sites/default/files/inline-files/Manual%20on%20Procedural%20Aspects.pdf; UNFCCC: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/02_0.pdf; UN General Assembly: https://www.un.org/en/ga/about/ropga/index.shtml; World Heritage Committee: https://whc.unesco.org/document137812&usg=AOvVaw3ki1HOhuwcog0pRa_u1ALd&opi=89978449.

28 European Parliament, Rules of Procedure of the European Parliament, May 2023, Rule 171.

29 Deutscher Bundestag, Geschäftsordnung, 2 July 1980 (BGBl. I S. 1237), § 45.

30 Votes concerning the German Constitution, any federal law or the Rule of Procedure themselves require different majorities; Ibid., § 48.

31 Deutscher Bundestag, ‘Hammelsprung’, https://www.bundestag.de/services/glossar/glossar/H/hammelsprung-444858.

32 Die Zeit, ‘AfD scheitert vor Gericht im Streit um Hammelsprung’, Die Zeit, 24 September 2019; https://www.zeit.de/politik/deutschland/2019-09/bundesverfassungsgericht-afd-hammelsprung-bundestag-antrag-abgelehnt.

33 Deutscher Bundestag, ‘Abstimmungen’; https://www.bundestag.de/services/glossar/glossar/A/abstimmungen-245316.

34 UNGA, Resolution 362 (IV) Methods and Procedures of the General Assembly, 22 October 1949.

35 Emphasis added; UNGA, XIII. Committees, Rule 108.

36 Convention on Wetlands of International Importance, especially as Waterfowl Habitat Convention on Wetlands of International Importance especially as Waterfowl Habitat (adopted 2 February 1971, entered into force 21 December 1975) 996 UNTS 245 (amended 1982 and 1987).

37 Emphasis added; Ramsar Convention, Rules of Procedure for meetings of the Conference of the Contracting Parties to the Convention on Wetlands of International Importance Especially as Waterfowl Habitat, 1 June 2015 (n27).

38 The proceedings of each Ramsar CoP can be accessed here: https://www.ramsar.org/official-documents.

39 Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (adopted 23 June 1979, entered into force 1 November 1983) 1651 UNTS 333.

40 The proceedings of each CMS CoPe can be accessed here: https://www.cms.int/en/meetings/conference-of-parties, accessed 7 August 2023.

41 United Nations, The Report of the Special Committee on the Rationalization of the Procedures and Organization of the General Assembly, UN Doc. A/8426 [1971].

42 See also Wang (n24), 727.

43 We turn to the issue of semantics in the IWC RoPs below.

44 Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries, ‘Presence’, https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/presence?q=presence.

45 Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (adopted 3 March 1973, entered into force 1 July 1975) 993 UNTS 243.

46 CITES, Rules of Procedure of the Conference of the Parties, https://cites.org/sites/default/files/eng/cop/E16-Rules.pdf, accessed 26 July 2023, Rule 7.

47 CITES, Summary Report of the Committee II meeting [2000] 28.

48 IWC (n16) Rule B.1.

49 Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries, ‘Attendance’, https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/attendance?q=attendance.

50 Ibid.

51 IWC (n16) 24.

52 Emphasis added; IWC (n16) Rule D.1.(a).

53 Original emphasis; Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries, ‘Participation’, https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/participation?q=participation.

54 Teachers were asked to solicit student participation; Those who declined participation were excused and sent back to the classroom; We were very pleased with the high level of participation in the charity events; the decline in voting and civic participation.

55 IWC (n16) Rule E.2.(a).

56 See further N Sellheim and J Schumacher, ‘Increasing the Effectiveness of the Bonn Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species’ (2022) 25 Journal of International Wildlife Law and Policy 367.

57 See IWC, Voting Rights and Contracting Government Contributions at the International Whaling Commission, FA/68/4.1.1/01/EN [2022].

58 IWC (n20) 3.

59 IWC (n15) Rule E.1.

60 Even though China is an IWC member, it has not participated in many meetings in the past.

61 D Panke, ‘Absenteeism in the General Assembly of the United Nations: Why Some Member States Rarely Vote’ (2014) 51 International Politics 729.

62 Available at https://www.youtube.com/@IwcInt.

63 In case of connectivity problems, it could also possible for other members to represent the fully absent member for as long as these technical issues persist.