ABSTRACT

Purpose

To assess the inclusivity of on-farm demonstration across Europe, in relation to age, gender, and geographical location of participants.

Methodology

The paper is based on a survey of 1162 on-farm demonstrators (farmers and organisations) and three supra-regional workshops.

Findings

Overall, on farm-demonstrations were found to be engaging young(er) farmers who are at a career stage of being able to implement long-term innovations. However, across Europe demonstrations were primarily attended by men. On-farm demonstrations were most common in Northern Europe, where advisory services brought together multiple AKIS actors. There were fewer on-farm demonstrations in Southern Europe, where demonstrations were more likely to be led by research institutes or individual farmers. Eastern Europe is notable for greater diversity in terms of gender and age of demonstration participants. Within countries, on-farm demonstrations occurred more frequently in regions of high agricultural profitability; more remotely located farmers had fewer opportunities to participate.

Practical implications

Demonstrations led by public and privately funded advisory services appear to attract primarily male farmers, thus reinforcing gendered patterns of participation in European agriculture. The location of advisory services and research institutes in high profitability locales disproportionately privileges farmers located there. More targeted efforts are required to ensure the participation of farmers who are female, older and located in less productive regions.

Theoretical implications

The paper draws attention to the lack of inclusivity of on-farm demonstration, developing a conceptual framework based on Lukes’ three faces of power.

Originality

The paper utilises the first European-wide inventory of on-farm demonstration to assess inclusivity.

1. Introduction

‘Inclusive Growth’ is one of the European Commission’s (EC) (Citation2020) three priorities for Europe’s social market economy in the twenty-first century.Footnote1 In the Europe 2020 Strategy, ‘inclusive growth’ refers to ‘a high-employment economy delivering economic, social, and territorial cohesion’ (Citation2020, 16). This is achieved through skill development,ensuring that economic growth spreads to all parts of the European Union (EU) and enabling access and opportunities for all throughout the lifecycle. As such, economic development in the EU is specifically connected to ensuring skill development across ages and geographical locations. The EC’s 2020 Strategy also identifies the need for policies to promote gender equality. Gender mainstreaming has been an official policy approach in the EU since the 1990s (European Parliamentary Research Service Citation2019), obliging the European Community to ‘eliminate inequalities and promote equality between women and men in all its activities’ (European Parliament Citation2020). Within the EU, inclusivity is thus understood as both a social justice issue and economic development imperative. In this paper we consider the inclusivity of a well-established form of agricultural knowledge exchange: on-farm demonstration. We focus specifically on the success of on-farm demonstration organisers in enabling inclusivity in relation to gender, age, and geographical location.

On-farm demonstration has been an important component of agricultural extension practice in Europe since the early twentieth century, with roots stretching back hundreds of years (Burton Citation2020). Through on-farm demonstration, innovations and novel practices can be developed, tested, and exchanged in farming networks. This study addresses a wide range of demonstration activities, including on-farm events organised by farmers, agricultural advisors, NGOs, charities, scientists, and industry professionals on farmer- or institutionally-owned farms (See Sutherland and Marchand Citation2021). Activities can range from one-off half day events, to regular meetings occurring over the course of years (e.g. ‘monitor farms’, Prager and Creaney Citation2017). The formats of on-farm demonstrations are thus diverse and are carried out by a wide range of European Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation Systems (AKIS) actors through their extension activities.

Within the European AKIS, recent literature has drawn attention to the inclusivity of extension services (e.g. Knierim et al. Citation2017; Prager, Creaney, and Lorenzo-Arribas Citation2017; Kinsella Citation2018; Dunne, Markey, and Kinsella Citation2019). Concerns have arisen in part from the privatisation of advisory services (Labarthe and Laurent Citation2013; Dunne, Markey, and Kinsella Citation2019; Haug Citation1999). The increasing plurality of advisory services (Knierim et al. Citation2017) and rising dependence on fee-for-service business models (Sutherland et al. Citation2017) disadvantages some farming types. Knierim et al. (Citation2017), in their European study, found that women, young farmers, part-time farmers, and farm employees are rarely identified as major target groups for any form of advisory services. In his study of ‘hard to reach’ farmers in Ireland, Kinsella (Citation2018) identified important age distinctions in engagement in extension services: both older farmers without successors and younger farmers who were working off-farm were considered ‘hard to reach’. Failure to engage these farmers is an issue for the economic vitality of the agricultural sector: young farmers in particular are considered an important source of innovation (Regidor Citation2012), receiving targeted European subsidies for this reason (Zagata and Sutherland Citation2015).

Ample literature has demonstrated issues of gendered access to contemporary extension practices, but this has focused primarily on the developing world. Gender was the subject of an entire special issue of this journal in 2013 (Jafry and Sulaiman Citation2013), and numerous subsequent papers (e.g. Rice et al. Citation2019; Lamontagne-Godwin et al. Citation2017, Citation2018, Citation2019), but has received considerably less attention within Europe. A Greek study (Charatsari, Černič Istenič, and Lioutas Citation2013) has found that that despite willingness to participate in agricultural extension and educational programmes, women’s actual participation is restricted by the perception that these programmes are designed for male farmers. Prager, Creaney, and Lorenzo-Arribas (Citation2017) propose that ensuring all client groups are covered – including women and young farmers – should be included in system-level assessment of advisory services. As a well-established mechanism of agricultural extension, on-farm demonstration may similarly omit particular cohorts, reinforcing a gap in innovation supports.

Geographical distinctions in European AKIS have been identified in multiple EU projects (e.g. PRO AKIS – Knierim et al. Citation2017; Prager, Creaney, and Lorenzo-Arribas Citation2017; SOLINSA – Moschitz et al. Citation2015; Tisenkopfs et al. Citation2015) but tend to focus on national level distinctions. Common patterns resulting from the differential development of agriculture (particularly under socialism in Central and Eastern Europe) are expected to yield supra-regional (Northern, Southern, and Eastern Europe) patterns. Published literature is already demonstrating that fewer advisory services are available for farms located in remote regions (e.g. Sutherland et al. Citation2017). We therefore consider sub-national, national, and ‘supra-regional levels’ with a view to better understanding the inclusivity of on-farm demonstration activities at these levels.

The paper addresses the following research questions:

What are the relationships between gender, age, and geographic location in participation in on-farm demonstration in Europe?

What types of demonstration organiser are achieving greater inclusivity in provision of on-farm demonstration?

To address these questions, we develop a conceptualisation of inclusivity grounded in Lukes’ three faces of power and apply it to a unique dataset of on-farm demonstrations across Europe.

2. Conceptualising power and inclusivity

The concept of inclusion does not have a formally agreed definition (Oxoby Citation2009). The EC’s usage of the term, described in the Introduction, clearly links it to social cohesion. The United Nations (UN) similarly defines an inclusive society as ‘one that rises above differences of race, gender, class, generation, and geography to ensure equality of opportunity regardless of origin’ (UN Citation2010, 3). Inclusivity is thus about ensuring that everyone – regardless of race, gender, age, and location – has access to the same opportunities. The notion of inclusive access to opportunities replaced poverty as a major concern of European social policy in the 1990s, when it became recognised that poverty was more than a distributional issue (i.e. lack of resources), but a reflection of low social integration, lack of participation, and powerlessness (Shortall Citation2008). Resultant policies tend to utilise the term ‘social exclusion’, which places the emphasis on the processes underlying inequalities (Shucksmith Citation2012).

Although there is widespread agreement that inclusivity is an important societal goal, there is considerable debate about how to measure it (UN Citation2010; Huxley Citation2015). Inclusivity could arguably be achieved when the characteristics of the participating population approximate those of the population as a whole (e.g. in terms of race, gender, class, generation, etc.). The weakness of this approach is that it is quite a blunt instrument, often failing to recognise regional differences, and does little to identify the underlying power dynamics that enable or disable societal participation in various forms. Shucksmith (Citation2000, 12) argues that ‘processes of social exclusion and inclusion … should therefore be analysed in relation to the means by which resources and status are allocated in society, and especially in relation to the exercise of power’. This is not to say that there is no individual agency or responsibility, but when there are major gaps between the characteristics of populations participating in (in this case) demonstration and what we would expect (for various reasons), this strongly suggests that the gaps are structural – i.e. that there are power dynamics at play.

In this paper we analyse statistics based on gender, age, and geographical location of demonstration participants. We interpret these statistics utilising feedback from stakeholder key informants who are familiar with the underlying issues and can inform our understanding of supra-regional (Northern, Eastern and Southern European), national and sub-national geographical patterns in on-farm demonstration provision and associated power dynamics. We base our conceptualisation of power on Lukes (Citation2005), who draws on Bourdieu’s tenet that people internalise power dynamics as part of their ‘internalised disposition to act’ or ‘habitus’ (Bourdieu Citation1984). Lukes (Citation2005) describes three ‘faces’ of power, placing particular emphasis on unconscious power dynamics. The first face of power is the power to achieve compliance. This is the form of power that is most easily recognised: power over people or things. In relation to on-farm demonstration, this is the authority of the organisers: the power to hold a demonstration (i.e. the resources and determination to host the event). Event organisers have the power to decide where a demonstration is held, what activities are involved, and to whom it is advertised. In the case of farmer-organised demonstrations, the host farmers themselves have this power. Lukes’ second face of power is the power to influence the context in which decisions are made – this is the power to influence who makes the decisions. In relation to on-farm demonstration, this is the power to allocate funding for demonstrations, and to establish governmental and institutional priorities for demonstration, which set the parameters within which institutional actors can organise demonstrations (e.g. on what topics, for what audience, and what type of learning needs should be addressed).

Lukes (Citation2005) third face of power is the power to influence what people think is important enough to challenge: embedded normative beliefs about the ‘natural state’ of affairs, which reinforce the status quo. The third face of power thus includes social norms around the roles and suitability of different cohorts for on-farm demonstration: women and young people may feel that demonstrations are for others (i.e. are not appropriate for them to attend). Demonstration organisers may also not see a need for women or young people to participate. Trauger et al. (Citation2008) in their US research into agricultural education and supports, argue that norms around the role of different farm household members lead to broader marginalisation of these cohorts by advisors and educators: women in their study were perceived as ‘farm wives’ and ‘book-keepers’ rather than farmers, and therefore not considered to be candidates for advisory service intervention. The perception of farm successors and employees as outside of the decision-making process could similarly marginalise them as candidates for participating in on-farm demonstration. Research into embodiment demonstrates how bodily characteristics such as age and gender intersect with practices that then become associated with those bodies (e.g. linking men to machinery and women to domestic labour) (Brandth Citation2006; Haugen and Brandth Citation1994). If the practice of participating in demonstrations becomes associated with particular body types (e.g. older, male) then this is likely to become normative and unchallenged within the industry.

3. Research methods

This paper is based on a survey of 1162 on-farm demonstrators across Europe and three ‘supra-regional workshops’ undertaken in 2017/2018. The PLAID (Peer to Peer Learning: Accessing Innovation through Demonstration) and AgriDemoF2F (Enhancing peer to peer learning) projects funded by the EC, collaborated to develop the first European inventory of on-farm demonstration, which has been expanded and operationalised into active ‘thematic networks’ by the NEFERTITI project. Consortia members and nine subcontractors (including both public and private advisory services, small to medium-size companies (SMEs), research institutes, and universities) compiled national inventories utilising a standardised questionnaire developed by consortia members. Participants were sourced utilising a combination of existing networks, national AKIS inventories produced through the PRO AKIS FP7 project, and internet searches. Following the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), all participants in the survey gave written permission for their data to be included in the inventory. The findings from the national inventories were presented, discussed, and validated at Supra-regional workshops, with PLAID, AgriDemo-F2F and NEFERTITI consortium members, stakeholder representatives, and members of the International Advisory Board. These workshops were held in Leuven (Belgium), Venice (Italy), and Krakow (Poland) in 2018.

The Europe-wide inventory (the dataset for this paper) comprises the EU 27,Footnote2 Norway, Serbia, and Switzerland. Data was collected at two levels: organiser (farmer or organisation) and demonstration. Organisers frequently organise multiple demonstrations, with different event structures and target audiences. The maximum number of demonstrations reported was capped at 10 per organisation, to reduce questionnaire fatigue. In total, 1162 demonstration organisers completed the survey.

The primary features identified in the inventory can be found on-line at www.farmdemo.eu. This paper focuses on the age, gender, and geographical location of participants. Geographic distinctions were made at country level and divided into the three regions where Supra-regional workshops were held:

Northern Europe: Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK;

Eastern Europe: Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia;

Southern Europe: Austria, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Malta, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain.

This geographical distinction is based on the differential histories of agricultural structure in Europe: for example, new EU member states have a shared history of collectivised agriculture which impacts on the current structural conditions of farming and the advisory services available.

Participants in the supra-regional workshops were asked the following questions:

What are the most common topics and purposes of demonstration?

Who are the major providers and organisers of on-farm demonstrations?

How common is it for farmers to lead demonstrations?

Are there particular regions where there are more demonstrations than others?

What is the balance of demonstration participants and organisers in terms of age and gender?

What are the major differences between countries – and what are the reasons for such differences?

The discussions at these meetings were recorded in note form and compiled into supra-regional reports. These supra-regional reports are the source material for the qualitative data presented in this paper.

For statistical analysis of the inventory, gender and age-related access issues were based on the question ‘Who is your MAIN audience?’ where respondents were offered multiple choice responses: ‘over 90% male’, ‘between 75% and 90% male’, ‘about 50/50 male/female’, ‘between 75% and 90% female’, and ‘over 90% female’; and ‘under 25’, ‘25-40’, ‘40-55’, ‘55+’, and ‘all ages’. Counts of the variable ‘over 90% female’ were so low (n = 11) that they were recoded with variable ‘between 75% and 90% female’ into variable ‘over 75% female’. The primary variables comprise self-reported estimates of survey participants; inferences must be treated with some caution.

It is important to note that although this dataset is substantial and involves a considerable cross section of European demonstration activities, it is not representative. Data collectors in every country reported that there were cases of on-farm demonstration where demonstration organisers did not wish to participate in the inventory. The European funders of the research specifically requested that large commercial providers of demonstration (e.g. input and machinery suppliers) be excluded; the inventory was intended to enable networking between demonstration farms, not to promote large companies. The use of personal networks to engage participants led to higher concentrations of demonstration being identified in geographic proximity to the data collectors. Some 25% of demonstration organisers reported 10 demonstrations,Footnote3 suggesting that these organisations could be underreporting their activity. In addition, 421 of 1162 demonstration organisers (36%) did not report on the gender characteristics of their audiences (i.e. their survey responses were incomplete).

Data analysis of demonstration participation is based on the individual demonstrations for which the relevant characteristics (e.g. age, gender, demonstration funder) was reported. Data was included in cross-table analysis on a pairwise basis: due to missing values for some questions, there are differences in sample sizes for individual comparisons. Analysis was conducted utilising Chi-Square test of independence to determine whether variables are statistically associated with each other, with significance at the 95% confidence level (p = .05). This is one of the most commonly utilised methods of statistical analysis for answering questions about the association between categorical variables (Franke, Ho, and Christie Citation2011). The supra-regional reports and synthesis report for the inventory, along with other project reports and materials, can be found at www.farmdemo.eu.

It is important to note that this paper focuses on three specific characteristics reflected in the provision of on-farm demonstration. Other socio-demographic patterns were identified in the supra-regional workshops, particularly educational achievement. Higher educational achievement appears to lead to a pattern of life-long learning, which includes participation in on-farm demonstrations when these are available. There was also concern raised that the enthusiasm of farmers for on-farm demonstration is not necessarily matched by skills in training and communication. These issues are further addressed by other papers in this special issue (e.g. Marchand et al. Citation2021; Ingram et al. Citation2021)

4. Results

Findings are divided into two sections which follow the research questions: differential participation in on-farm demonstration, and the inclusivity achieved by AKIS actors in their provision of demonstration. provides basic descriptive statistics of the dataset. includes descriptive statistics for the gender and age of participant variables.

Table 1. Supra-regions and five most common topics of on-farm demonstration.

Table 2. Age and gender profile of on-farm demonstration participants.

The frequency of topics suggests a good representation of agricultural sectors across Europe, providing a surface validity to the dataset. Discussions with supra-regional workshop participants confirmed that on-farm demonstrations were most common in Northern Europe. Farmer-led demonstration is relatively new, but popular in Eastern Europe, with greater frequency of demonstration reported than in Southern Europe. Participants in the Southern Europe supra-regional workshop reported that demonstration activities are declining in this region, in large part due to reduced funding and access to public advisory services. In total, organisers who participated in the survey estimated that there were over 680,000 farmer visits to their reported demonstrations.

4.1. Differential participation in on-farm demonstration

The survey analysis found that gender and age were significantly associated with participation in demonstration [p = .000]. demonstrates a significant association between age and gender of participants: events with higher percentages of women were more likely to be those events where there were more individuals under the age of 40.

Demonstration organisers reported that about half of demonstrations were attended by ‘all ages’ (), but where organisers specified age-related distinctions, participants were somewhat younger than the population of European farmers. Eurostat figures from 2016 identify just 11% of farmers as under the age of 40 (Eurostat Citation2018), whereas demonstration organisers identified 912 of the 3944 (23.1%) demonstrations as predominantly participated in by farmers under 40. Some 32% of European farmers are over 65 (Ibid.), a cohort which is much less common amongst on-farm demonstration participants. Only 145 demonstrations (3.7%) were reported which primarily reached farmers over the age of 55. This finding was confirmed at all of the supra-regional workshops, where participants reported that participants in on-farm demonstration events were typically younger than the population of farmers as a whole, although not necessarily ‘young farmers’ by European policy definitions (under the age of 40).Footnote4

Descriptive analysis of the dataset revealed that 61.2% of demonstrations reported were primarily attended by men (i.e. over 75% male), although about one third of demonstrations were reported to have an equal representation of male and female participants (). Demonstrations that were attended predominantly by women were unusual in the dataset. In discussing gender, the supra-regional workshop participants could not identify specific barriers to female participation, proposing that lack of female attendance reflected the demographic characteristics of the industry, and lack of interest in particular topics. Workshop participants explained the comparatively high incidence of farmers under 55 in attendance as reflecting higher levels of openness to innovation. This demographic characteristic was viewed favourably, as evidence that on-farm demonstration is engaging those farmers who are most likely to engage in innovative activities on their farms. Low participation of women was not identified as a problem for most supra-regional workshop participants.

Age and gender were statistically associated with geographical location at supra-regional level (, p = .000). Participants in Northern Europe were most commonly described as being in the ‘all ages’ or ‘40-55 years’ categories, suggesting that they are younger than the average age of farmers reported by Eurostat (Citation2018). However, demonstration participants in Eastern and Southern Europe were more commonly described as between 25 and 40 years of age, or ‘all ages’, suggesting that they are younger than in Northern Europe. Eastern Europe appears more egalitarian in terms of gendered participation, which may reflect the higher percentages of female-led farms located there (European Commission Citation2019Footnote5). In Eastern and Southern Europe, almost half of reported demonstrations were attended equally by both genders, although male-dominated events are still common. Participation in on-farm demonstrations in Northern Europe was very male-dominated, with over 70% of demonstrations reporting over 75% male participation.

Table 3. Gender and age distinctions of on-farm demonstration participants by Supra-region.

Discussions at the supra-regional workshops drew out national distinctions within the supra-regions. Although participants at the Northern Europe supra-regional workshop agreed that demonstrations were typically male-dominated in most countries, this was not true of Norway, where more equal gender representation was reported. Norwegian participants also reported more young people participating in on-farm demonstrations. At the Southern Europe supra-regional workshop, participants from Portugal and Slovenia reported a gender-balanced pattern in on-farm demonstration participation. The Southern Europe supra-regional workshop confirmed the higher presence of younger farmers at on-farm demonstration events.

In all three supra-regional workshops, participants agreed that within countries, regions and sectors where agriculture is more profitable tend to have more on-farm demonstrations, reflecting the higher concentration of advisory services and research institutes located in these areas. These sub-national regions also tend to be more centrally located. Although they are often characterised by larger farms, this is not always the case: participants in the Southern Europe supra-regional workshop identified wealthier regions like Emilia Romagna or Bolzano in Italy and Navarra in Spain as having particularly plentiful on-farm demonstrations; these are regions where more profitable farms are in viticulture or horticulture and thus smaller in scale. There were different national patterns in farmer willingness to travel to demonstrations. For example, farmers in northern Sweden routinely travel to southern Sweden to gain access to on-farm demonstrations, whereas farmers in northern UK (Scotland) were unlikely to travel outside of their own regions. Concerns about national barriers (particularly in Southern Europe) were attributed to the underfunding of Farm Advisory Services (FAS) and sub-national barriers (availability of demonstrations to farmers in remote locations, or farmers with smaller and less commercially viable farms) were specifically raised at the supra-regional meetings.

The supra-regional workshops also noted that although there was a majority of men attending demonstrations, demonstration organisers tend to be more gender-balanced. This reflects more equal numbers of male and female agricultural advisors. Women who were raised on farms but do not inherit them, often remain in the agricultural sector as agricultural advisors (Shortall et al. Citation2017)

4.2. Inclusivity of AKIS actors in organising demonstrations

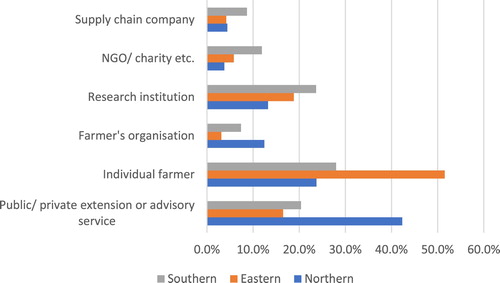

In this section we consider whether different types of on-farm organiser and funder attract a different socio-demographic cohort to their demonstrations. Inventory participants were asked to identify the primary organisers and funders of each of their demonstrations.Footnote6 Primary event funder and primary organiser were significantly associated (, p = .000).

Table 4. Most important demonstration funder by primary organiser.

demonstrates the complexity of organisers and funders in Europe’s pluralistic AKIS: although demonstration organisers tend to rely first on their own resources for demonstration, they also frequently relied on external funding. The high number of demonstrations organised and funded by individual farmers is particularly notable, representing 22.7% (n = 938) of demonstrations in the dataset. Publicly funded demonstrations accounted for 21.2%. The option for ‘self-funded’ was intended for farmers who organised demonstrations; the incidence of self-funded events indicated by other organisers suggests that they distinguished between use of their own institution’s funding, versus that funding made available to the demonstration by an external source (e.g. by a research project).

It is important to note that ‘commercial demonstrations’ by major companies oriented towards product sales were intentionally excluded from the inventory; supply chain company-led and funded demonstrations are therefore under-represented (comprising 9.3% of demonstrations in the dataset). These companies clearly play a role in funding demonstrations organised by others, particularly extension services. Supra-regional workshop participants in Eastern Europe identified a trend towards international suppliers of seeds, fertilisers, crop protection products, and machinery becoming increasingly important for on-farm demonstration, often crossing national borders to organise demonstration activities.

In considering these funders and organisers geographically, there were clear supra-regional distinctions. Whereas public and privately funded advisory services were most common in Northern Europe, organisation of on-farm demonstration in Eastern and Southern Europe was more commonly attributed to individual farmers (). In keeping with the ethos of peer-to-peer learning, all of the supra-regional workshops reported that farmers were the most common demonstrators, confirmed by the statistical analysis (Main demonstrator = farmer: 50.5% Northern Europe, 61.3% Eastern Europe, and 40.0% Southern Europe, n = 4393, averaging to 51.4% across all demonstrations) (p = .000). In Southern Europe, a stronger role was played by research institutes, in keeping with the stronger role of researchers in on-farm demonstration, but farmers remain the most common demonstrator.

In terms of organising demonstration, advisors played a much stronger role in Northern than Southern Europe (). In Southern Europe, farmers, researchers, students, and farmers themselves appear to be taking the place of advisors in demonstrating.Footnote7 The supra-regional workshops reported that the Northern Europe supra-region was characterised by more collaborative interactions between demonstration providers, with public and private advisory services acting as the ‘glue’ or integrating force for bringing members of the AKIS together. Within Southern Europe, particularly Mediterranean countries (e.g. Portugal, Spain, Italy, Greece), public extension services have largely disappeared, and private extension services have not arisen to take their place. This has resulted in a landscape where on-farm demonstrations were more commonly organised by research institutes or farmers themselves. The Southern supra-regional workshop participants expressed concern that this is leading to fragmentation, a lack of attention to sustainability and farming system approaches (e.g. on-farm demonstrations instead tend to be focused on specific crops and single technologies), and limited opportunities for many farmers to participate in demonstrations at all. While farmer-led demonstrations were welcome, all of the supra-regional reports include recommendations for specific training for host farmers in particular (as well as funding) to ensure that they offer high quality events.

Participants at the supra-regional workshops also identified national patterns in leadership of on-farm demonstrations (). Although extension or advisory services clearly play a major role in demonstration in many countries, there were countries in each supra-region where they do not play an important role: Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, Greece, Malta, Portugal, Serbia, and Slovakia. Notably, academic and research institutes play important roles in demonstration, evident in all but the smallest countries: Malta and Cyprus.

Table 5. National patterns in provider of on-farm demonstration.

The demonstration organiser was significantly associated with the gender and age of participants (, p = .000). In relation to age, advisory and extension services reported that over three quarters of their events have at least 75% men in attendance. Supply chain companies similarly reported high percentages of male attendance. In contrast, NGOs, charities, and research institutions reported over a third of their events to be gender-balanced in terms of visitor profile. Individual farmers were the most likely to describe their participants as equally composed of male and female attendees (50.9%), and they were the most likely to host events which were primarily attended by women. The majority of on-farm demonstrations were attended by ‘all ages’, but where respondents identified age-based distinctions, younger farmers (under the age of 40) were more commonly reached by individual farmers, farmers’ organisations, and NGOs or charities. Older farmers (over the age of 55) were not typically a major participant for any of the organisers.

Table 6. On-farm demonstration by organiser by age and gender of participants.

5. Discussion

This paper presents analysis of the first comprehensive inventory of on-farm demonstration in Europe, integrating data from 27 EU countries, Norway, Serbia, and Switzerland. Analysis of the inventory demonstrates that on-farm demonstration is a popular tool for knowledge exchange, engaging hundreds of thousands of farmers, often in a leadership capacity.

Analysis presented in this paper demonstrates that the inclusivity of on-farm demonstration varies widely across Europe in geographic terms. On-farm demonstration is more common in countries with well-funded advisory services (private or public), particularly in Northern Europe. Within countries, regions with more productive or profitable agriculture also have higher numbers of on-farm demonstrations. This reflects the co-location of advisory services, input supply companies, and research institutes in profitable locations. These regions appear to be self-reinforcing hubs of farmer innovation and access to information: advisory services and input companies in particular are likely to locate in regions where farmers can afford their services; those service providers then find it most cost effective to focus their services on local farmers.

In terms of demographics, the profile of on-farm demonstration participants is considerably different from that of farmers across Europe, reaching participants in the 25 to 55 age bracket, who are well placed to make longer-term innovations on their farms. This is consistent with Irish findings by Kinsella (Citation2018) that older farmers are less likely to engage with advisory services but counters his findings about younger farmers. Knierim et al. (Citation2017) also found that younger people were less likely to engage with advisory services. There are several potential reasons for the higher participation of young people in on-farm demonstration. First, it is important to clarify that the participants were younger than the age profile of European farmers in overall, but not necessarily ‘young farmers’ (under the age of 40). Second, as proposed by supra-regional workshop participants, younger farmers may be more interested in accessing information on the innovations demonstrated, because they are in a position to benefit from these innovations long-term. Third, the open format of demonstrations – typically held outdoors and attended by groups of people – may be less daunting (or costly) for younger farmers than the one-to-one interaction with agricultural advisors included in Knierim et al. and Kinsella’s studies. Fourth, the higher percentage of younger participants suggests that farming successors – typically unaccounted for in farming statistics (Zagata and Sutherland Citation2015) – are also attending demonstrations.

Participation in on-farm demonstration is also gendered, particularly in Northern Europe. To some degree, this reflects the gender profile of European farmers, with higher percentages of women attending demonstrations in Eastern Europe, where women are more commonly identified as farmers (European Commission Citation2019). More egalitarian gender relations have been noted amongst young farmers in general across Europe (EIP Agri Focus Group Citation2016), although this is not evident in Eurostat figures, where only 23% of farmers under the age of 40 were identified as female (Eurostat Citation2016), demonstrating the intersectionality of inclusivity issues. In the present study, the relationship found between gender and age of participants suggests that increasing the emphasis on attendance by younger farmers or women will have reciprocal benefits.

In many Northern European countries, advisory services form the ‘glue’ that brings together multiple AKIS actors to provide jointly organised and on-going programmes on on-farm demonstration. The lack of advisory services in Southern Europe was linked to the fragmented and sporadic nature of on-farm demonstration discussed in the supra-regional workshops. However, although farmers in Southern Europe clearly had fewer opportunities to participate in on-farm demonstration, when they did so, a broader sociodemographic range of participants was achieved. Jansen et al. (Citation2010) argued that failure to access advisory services did not necessarily denote lack of access to information; some farmers were seeking information elsewhere. In all three supra-regions, this also includes farmers organising informal on-farm demonstration for peer groups. The inclusivity of these demonstrations may reflect the role of the host family in organising the demonstration, creating a perception that multiple family members are welcome.

Research institutions clearly play an important role in on-farm demonstration in many European countries and appear to be more successful at including women and young farmers than advisory services. There are number of potential reasons for this. Advisory services and input supply companies may orient their advertising of on-farm demonstration to their ‘clients’, and therefore place more emphasis on attracting ‘primary farmers’, a known market failure of pluralised advisory services (Prager, Creaney, and Lorenzo-Arribas Citation2017). Privatisation of advisory services may therefore have had gendered implications. Research institutions may also be more socially aware of gender issues, and actively engaged in programming for students, thus targeting younger and female participants. The importance of identifying and effectively reaching target audiences is addressed in Adamsone-Fiskovica et al.’s (Citation2021) paper on success factors for on-farm demonstration in this issue.

In framing this paper in relation to inclusivity and Lukes (Citation2005) three faces of power it is apparent that farmers themselves have a major role in the first and second faces of power, organising and funding their own on-farm demonstration events. When they organise on-farm demonstrations, these events are more likely to be attended by women and younger farmers. Farmers are also more likely to be the organisers of demonstration in countries where there is limited public funding for advisory services. However, when this power is held by advisory services and input supply companies, on-farm demonstration organisers attract older and male participants, and tend to organise demonstrations in areas where more profitable farms are located. It therefore appears that public and private advisory services may be reinforcing gender and age-related norms in the agricultural sector, and contributing to the lack of access to demonstration for farmers in remote areas.

The lack of concern about gender at the supra-regional workshops reflects Lukes (Citation2005) third face of power: the predominantly male attendance at demonstrations is accepted as normal, characteristic of the gendered nature of the industry, rather than a standard to be challenged. When younger farmers attend events, this is considered laudable, but there was no concern expressed about enabling access for older farmers, or for increasing female attendance. However, supra-regional workshop participants were concerned about geographical issues, arguing steps to be taken to increase on-farm demonstration in countries and locales where there is limited access.

6. Conclusion

As described in the introduction, increasing inclusivity has been identified as an important priority for the European Commission, essential to economic, social, and territorial cohesion. The present analysis demonstrates that although the provision of on-farm demonstration is challenging age-related norms in the agricultural sector, there are clear inequalities relating to gender and geographic location. This finding may link to the growing body of evidence about the adverse impact of the privatisation of advisory services on access to advice (e.g. Labarthe and Laurent Citation2013; Sutherland et al. Citation2017). We suggest that further scrutiny of the inclusivity of recipients of public funding in particular is warranted, to ensure that their state funding is employed in a way that aligns with European policy priorities. The national CAP Strategic Plans being produced in 2020, which will be informed by findings from this and other projects (see the EU SCAR-AKIS Citation2019 report), are intended to specifically yield a more ‘joined up AKIS’ (EIP Agri Citation2020), thus offering the potential to address geographical issues related to fragmentation. However, funding for the FAS remains a national-level decision, meaning that the amount of funding for advisory services – particularly in Southern Europe – may remain low.Footnote8 Promotion of gender equality remains problematic, particularly in light of the limited gender-disaggregated data available at European level (Shortall Citation2010). New strategies for on-farm demonstration activities to reach under-represented groups (e.g. virtual or on-line demonstration, additional supports to enable demonstration in remote regions), should be considered in these AKIS Plans, and included in reviews of Europe’s FAS.

At a practical level, there is an evident need for awareness raising and unconscious bias training for advisory services and input companies. The economic benefits of inclusivity do not appear to have been realised by these demonstration providers. There is also an apparent disconnection from the academic literature on extension. The disconnection between natural science and its application advisory practice is well established: many advisory services have limited ‘back office’ funding or activities to enable new scientific research to be integrated into advice provision (Labarthe and Laurent Citation2013; Prager et al. Citation2016). This paper demonstrates the disconnection between social science and advisory service practice. The importance of inclusivity is becoming established in the social science literature (e.g. Prager, Creaney, and Lorenzo-Arribas Citation2017; Knierim et al. Citation2017) but these ‘best practices’ in service provision and evaluation do not appear to be making it into practice.

In terms of advancing science, the ongoing patriarchal nature of European agriculture is well established (Shortall Citation2010). Geographical barriers to advisory service provision are also well known (Sutherland et al. Citation2017). Where this paper demonstrates particularly novel evidence is in revealing that on-farm demonstration providers are challenging age-based norms in the agricultural sector, but are less concerned with gendered participation. To date, the latter issue has primarily been addressed in the global South, where it is considered an important issue for increasing agricultural productivity (Lamontagne-Godwin et al. Citation2018; FAO Citation2011). Further investigation of the power dynamics underpinning inclusivity in European AKIS are warranted.

As a final note, we recognise that this paper focuses on the inclusivity of demonstration organisers. It is also important to consider participant perspectives. The more general topic of inclusivity in on-farm demonstrations goes beyond the structural factors singled out in this paper, as there are many other kinds of potential barriers at play in these types of learning environments. These include barriers related to farmer characteristics, those of individual and institutional providers of education and training, the learning content, the accessibility to learning opportunities, and the method of delivery (Fulton et al. Citation2003). It is therefore important to speak not only of structural, but also specific physical, economic, communicative, cognitive, and other types of external and internal factors either enabling or restricting the inclusivity of on-farm demonstrations.

Reflecting back to the Lukes (Citation2005) three faces of power, we argue that all three dimensions are at play in the inclusivity of on-farm demonstrations. It is not only about the decisions made by organisers about how they will market their demonstration, it is about power at the level of national authorities to support (or not) public extension activities which enable a diverse range of farmers to participate in on-farm demonstrations and define eligible beneficiaries. National and European authorities hold the power to encourage demonstration organisers to target and address groups in actual need of this type of instruction and communication. Lukes (Citation2005) third face of power is particularly important – the need to recognise the opportunity and importance of challenging demographic norms through on-farm demonstration provision.

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to all the PLAID, AgriDemoF2F and NEFERTITI project partners and subcontractors involved in collecting and analysing the national inventories and to the participants in the Supra-regional workshops who gave valuable input. We are particularly grateful to Cristina Micheloni and Harm Brinks for their work on the Supra-regional workshops and reports, and Jon Hopkins for his comments on an earlier version of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lee-Ann Sutherland

Lee-Ann Sutherland is Director of the International Land Use Study Centre at the James Hutton Institute. She leads research on farmer identify, gentrification of agriculture, agricultural knowledge systems, farm diversification, and social justice issues in the agricultural sector relating to gender, age, and land access. She has recently begun investigating the role of farming computer games in shaping agrarian imaginaries.

Rob J. F. Burton

Rob J. F. Burton is a professor level researcher (Forsker 1) at Ruralis: Institute for Regional and Rural Research in Trondheim, Norway. He has over 20 years’ experience in agricultural research in Europe and New Zealand, with his early work focusing on farmer behaviour and behavioural change. His current interest lies in understanding long-term transitions in agriculture through historical analysis.

Anda Adamsone-Fiskovica

Anda Adamsone-Fiskovica is a researcher at the Baltic Studies Centre in Riga, Latvia. She holds a master’s degree in Society, Science and Technology in Europe from Linkoping University and a doctoral degree in sociology from the University of Latvia. She has undertaken research on innovation policy, science communication, public understanding of science, and citizen engagement. A more recent academic interest is related to agricultural knowledge and innovation systems and farmers’ learning as well as food studies.

Claire Hardy

Claire Hardy a researcher at The James Hutton Institute Aberdeen, Scotland. She has a background in farm management a PhD in Aquaculture/Animal Behaviour from the University of Stirling she has a keen interest in farmer behaviour, peer-to-peer learning and decision making. She is following an interest in the use of digital media and particular virtual immersion to engage stakeholder groups in issues around innovation, climate change and health and wellbeing.

Boelie Elzen

Boelie Elzen is senior researcher at Wageningen Research in the Netherlands. He has a PhD in innovation studies and his research focus is on the analysis of sustainability transitions in agriculture. He is primarily interested bridging gaps between science an practice by being involved in various multi-stakeholder projects, both national and at the European level, where scientists and practitioners jointly try to make steps forward towards making agriculture more sustainable.

Lies Debruyne

Lies Debruyne is a senior researcher at the research group Agricultural and Farm Development of the Social Sciences Unit of ILVO (Flanders Research Institute for Agriculture, Fisheries and Food). Her main research interests lie in learning processes of farmers and other agricultural stakeholders, with a focus on the role of various formal and informal networks on learning. Furthermore, she looks into how such networks can support transitions in agriculture.

Sharon Flanigan

Sharon Flanigan is a qualitative social scientist in Social, Economic, and Geographical Sciences (SEGS) Group at the James Hutton Institute. She has a background in rural topics, primarily focussing on aspects of farming and tourism in rural areas. She is particularly interested in exploring opportunities for interaction, learning, and collaboration between people and groups (e.g. peer-to-peer, host-guest) in terms of effect on individuals, businesses, and communities.

Notes

1 The other two priorities are smart growth and sustainable growth.

2 Luxembourg was excluded from the inventory for logistical reasons.

3 All of the variables used in the analysis were completed for each demonstration.

4 Targeted European subsidies for young farmers restrict these to farmers who are under the age of 40 (Zagata and Sutherland Citation2015).

5 For example, Lithuania and Latvia are notable for the highest percentage of female-led farms in Europe, at 45%. The fewest female-led farms are in the Netherlands, Malta, Germany, and Ireland, where they range from 5 to 11% respectively.

6 Demonstration organisers also identified secondary and tertiary organisers and funders, demonstrating similar patterns to those presented here.

7 The Eastern Supra-regional workshop reported that advisory services play a stronger role in organising demonstrations than is evident in the inventory statistics. Subsequent sense checking of the data led to the discovery that translation issues meant that some Eastern European participants to identify demonstrations organised on farm as organised by farmers, when extension services had primarily organised the demonstration. We retained the Eastern European data in to demonstrate the importance of other organisers. The importance of advisors to on-farm demonstration in Eastern Europe is evident in .

8 For further information on the national CAP AKIS strategic planning process see: https://ec.europa.eu/eip/agriculture/en/event/eip-agri-seminar-cap-strategic-plans-key-role-akis

References

- Adamsone-Fiskovica, A., M. Grivins, R. J. F. Burton, B. Elzen, S. Flanigan, R. Frick, and C. Hardy. 2021. “Disentangling Critical Success Factors and Principles of On-Farm Agricultural Demonstration Events.” Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 27 (5): 639–656.

- Bourdieu, P. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Brandth, B. 2006. “Agricultural Body-Building: Incorporations of Gender, Body and Work.” Journal of Rural Studies 22 (1): 17–27.

- Burton, R. J. F. 2020. “The Failure of Early Demonstration Agriculture on Nineteenth Century Model/Pattern Farms: Lessons for Contemporary Demonstration.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 26 (2): 223–236. doi:10.1080/1389224X.2019.1674168.

- Charatsari, C., M. Černič Istenič, and E. D. Lioutas. 2013. “I’d Like to Participate, but … : Women Farmers’ Scepticism Towards Agricultural Extension/Education Programmes.” Development in Practice 23 (4): 511–525.

- Dunne, A., A. Markey, and J. Kinsella. 2019. “Examining the Reach of Public and Private Agricultural Advisory Services and Farmers’ Perceptions of Their Quality: The Case of County Laois in Ireland.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 25 (5): 401–414.

- EIP Agri. 2016. EIP-AGRI Focus Group New Entrants into Farming: Lessons to Foster Innovation and Entrepreneurship. Final report. https://ec.europa.eu/eip/agriculture/en/publications/eip-agri-focus-group-new-entrants-final-report.

- EIP Agri. 2020. EIP-AGRI Seminar CAP Strategic Plans: The Key Role of AKIS in Member States. https://ec.europa.eu/eip/agriculture/en/event/eip-agri-seminar-cap-strategic-plans-key-role-akis.

- European Commission. 2019. Females in the Field. More Women Managing Farms Across Europe. News Agriculture and Rural Development. https://ec.europa.eu/info/news/queens-frontage-women-farming-2019-mar-08_en.

- European Commission. 2020. A Strategy for Smart, Sustainable and Inclusive Growth. Communication from the European Commission 2020. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwidlfDR9LrqAhW7WxUIHWiyAZoQFjADegQIBBAB&url=https%3A%2F%2Fec.europa.eu%2Feu2020%2Fpdf%2FCOMPLET%2520EN%2520BARROSO%2520%2520%2520007%2520-%2520Europe%25202020%2520-%2520EN%2520version.pdf&usg=AOvVaw2vSdv5EcWXEKhq-KGXYzeu.

- European Parliament. 2020. Equality Between Men and Women. Fact Sheets on the European Union. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/factsheets/en/sheet/59/equality-between-men-and-women.

- European Parliamentary Research Service. 2019. Gender Mainstreaming in the EU: State of Play. At a Glance. Plenary – January 2019. http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=7&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwiI99ml_OTlAhWGSRUIHU8JB5IQFjAGegQIARAC&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.europarl.europa.eu%2FRegData%2Fetudes%2FATAG%2F2019%2F630359%2FEPRS_ATA(2019)630359_EN.pdf&usg=AOvVaw0O8-hB0KDlxHpbKsoBDzTq.

- Eurostat. 2016. Farming: Profession with Relatively Few Young Farmers. Eurostat News. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/DDN-20180719-1?inheritRedirect=true.

- Eurostat. 2018. Farm Structure Survey 2016. Of the 10.3 Million Farms in the EU, Two Thirds are Less than 5 ha in Size. Eurostat News Release 105/2018, 28 June 2018. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/en/web/products-press-releases/-/5-28062018-AP.

- EU SCAR AKIS. 2019. Preparing for Future AKIS in Europe. Brussels: European Commission. https://scar-europe.org/index.php/akis-documents.

- FAO. 2011. The State of Food and Agriculture, Women in Agriculture, Closing the Gender Gap in Agriculture. Rome. Report written by the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations.

- Franke, T. M., T. Ho, and C. A. Christie. 2011. “The Chi-Square Test: Often Used and More Often Misinterpreted.” American Journal of Evaluation 33 (3): 448–458.

- Fulton, A., D. Fulton, T. Tabart, P. Ball, S. Champion, J. Weatherley, and D. Heinjus. 2003. Agricultural Extension, Learning and Change. A report for the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. https://rirdc.infoservices.com.au/downloads/03-032.pdf.

- Haug, R. 1999. “Some Leading Issues in International Extension: A Literature Review.” Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 5 (4): 263–274.

- Haugen, M. S., and B. Brandth. 1994. “Gender Differences in Modern Agriculture: The Case of Female Farmers in Norway.” Gender and Society 8 (2): 206–229.

- Huxley, P. 2015. “Introduction to Indicators and Measurement of Social Inclusion.” Social Inclusion 3: 50–51.

- Ingram, J., H. Chiswell, J. Mills, L. Debruyne, H. Cooreman, A. Koutsouris, Y. Alexopoulos, E. Pappa, and F. Marchand. 2021. Situating Demonstrations Within Contemporary Agricultural Advisory Contexts: Analysis of Demonstration Programmes in Europe.” Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 27 (5): 615–638.

- Jafry, T., and R. Sulaiman V. 2013. “Gender Inequality and Agricultural Extension.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 19 (5): 433–436.

- Jansen, J., C. D. M. Steuten, R. Renes, N. Aarts, and T. J. G. M. Lam. 2010. “Debunking the Myth of the Hard-to-Reach Farmer: Effective Communication on Udder Health.” Journal of Dairy Science 93: 1296–1306.

- Kinsella, J. 2018. “Acknowledging Hard to Reach Farmers: Cases From Ireland.” International Journal of Agricultural Extension 6: 61–69.

- Knierim, A., P. Labarthe, C. Laurent, K. Prager, J. Kania, L. Madureira, and T. Hycenth Ndah. 2017. “Pluralism of Agricultural Advisory Service Providers – Facts and Insights From Europe.” Journal of Rural Studies 55: 45–58.

- Labarthe, P., and C. Laurent. 2013. “Privatization of Agricultural Extension Services in the EU: Towards a Lack of Adequate Knowledge for Small-Scale Farms?” Food Policy 38: 240–252.

- Lamontagne-Godwin, J., S. Cardey, F. E. Williams, P. T. Dorward, N. Aslam, and M. Almas. 2019. “Identifying Gender-Responsive Approaches in Rural Advisory Services That Contribute to the Institutionalisation of Gender in Pakistan.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 25 (3): 267–288.

- Lamontagne-Godwin, J., F. E. Williams, N. Aslam, S. Cardey, P. Dorward, and M. Almas. 2018. “Gender Differences in use and Preferences of Agricultural Information Sources in Pakistan.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 24 (5): 419–434.

- Lamontagne-Godwin, J., F. E. Williams, W. M. P. T. Bandara, and Z. Appiah-Kubi. 2017. “Quality of Extension Advice: A Gendered Case Study From Ghana and Sri Lanka.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 23 (1): 7–22.

- Lukes, S. 2005. Power: A Radical View. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

- Marchand, F., H. Cooreman, E. Pappa, Y. Alexopoulos, L. Debruyne, H. Chiswell, J. Ingram, and A. Koutsouris. 2021. “Effectiveness of On-Farm Demonstration Events in the EU: The Role of Structural Factors.” Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 27(5): 677–698.

- Moschitz, H., D. Roep, G. Brunori, and T. Tisenkopfs. 2015. “Learning and Innovation Networks for Sustainable Agriculture: Processes of Co-Evolution, Joint Reflection and Facilitation.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 21 (1): 1–11.

- Oxoby, R. 2009. “Understanding Social Inclusion, Social Cohesion, and Social Capital.” International Journal of Social Economics 36: 1133–1152.

- Prager, K., and R. Creaney. 2017. “Achieving On-Farm Practice Change Through Facilitated Group Learning: Evaluating the Effectiveness of Monitor Farms and Discussion Groups.” Journal of Rural Studies 56: 1–11.

- Prager, K., R. Creaney, and A. Lorenzo-Arribas. 2017. “Criteria for a System Level Evaluation of Farm Advisory Services.” Land Use Policy 61: 86–98.

- Prager, K., P. Labarthe, M. Caggiano, and A. Lorenzo-Arribas. 2016. “How Does Commercialisation Impact on the Provision of Farm Advisory Services? Evidence From Belgium, Italy, Ireland and the UK.” Land Use Policy 52: 329–344.

- Regidor, J. G. 2012. EU Measures to Encourage and Support New Entrants. European Parliament. Directorate-General for Internal Policies. Policy Department B: Structural and Cohesion Policies. Agriculture and Rural Development. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/note/join/2012/495830/IPOL-AGRI_NT(2012)495830_EN.pdf.

- Rice, M. J., J. M. Apgar, A.-M. Schwarz, E. Saeni, and H. Teioli. 2019. “Can Agricultural Research and Extension be Used to Challenge the Processes of Exclusion and Marginalisation?” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 25 (1): 79–94. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2018.1529606.

- Shortall, S. 2008. “Are Rural Development Programmes Socially Inclusive? Social Inclusion, Civic Engagement, Participation, and Social Capital: Exploring the Differences.” Journal of Rural Studies 24 (4): 450–457.

- Shortall, S. 2010. Women Working on the Farm: How to Promote Their Contribution to the Development of Agriculture. European Parliament. Directorate-General for Internal Policies. Agriculture and Rural Development.

- Shortall, S., L.-A. Sutherland, A. J. McKee, and J. Hopkins. 2017. Women in Farming and the Agriculture Sector. Final Report for the Environment and Forestry Directorate, Rural and Environmental Science and Analytical Services (RESAS) Division, Scottish Government. Scottish Government Riaghaltas na h-Alba gov.scot Social Research.

- Shucksmith, M. 2000. “Endogenous Development, Social Capital and Social Inclusion: Perspectives From LEADER in the UK.” Sociologia Ruralis 40 (2): 208–218.

- Shucksmith, M. 2012. “Class, Power and Inequality in Rural Areas: Beyond Social Exclusion?” Sociologia Ruralis 52 (4): 377–397.

- Sutherland, L.-A., L. Madureira, V. Dirimanova, M. Bogusz, J. Kania, K. Vinohradnik, R. Creaney, D. Duckett, T. Koehnen, and A. Knierim. 2017. “New Knowledge Networks of Small-Scale Farmers in Europe’s Periphery.” Land Use Policy 63: 428–439.

- Sutherland, L.-A., and F. Marchand. 2021. “On-farm Demonstration: Enabling Peer-to-Peer Learning. Editorial.” Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 27 (5): 573–590.

- Tisenkopfs, T., I. Kunda, S. Šūmane, G. Brunori, L. Klerkx, and H. Moschitz. 2015. “Learning and Innovation in Agriculture and Rural Development: The Use of the Concepts of Boundary Work and Boundary Objects.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 21 (1): 13–33.

- Trauger, A., C. Sachs, M. Barbercheck, N. E. Kiernan, K. Brasier, and J. Findeis. 2008. “Agricultural Education: Gender Identity and Knowledge Exchange.” Journal of Rural Studies 24 (4): 432–439.

- United Nations. 2010. Analysing and Measuring Social Inclusion in a Global Context. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. New York: United Nations.

- Zagata, L., and L-A. Sutherland. 2015. “Deconstructing the ‘Young Farmer Problem in Europe’: Towards a Research Agenda.” Journal of Rural Studies 38: 39–51.