ABSTRACT

Purpose

This study explores the intersection of gender and place with agricultural extension services to understand disparities in resource and information access and build community resilience in post-conflict Liberia. It emphasizes how such intersections may be further compounded by climate change and provides possible solutions.

Methodology

Using a community-based research approach, 352 surveys and 44 focus groups were conducted in 22 communities in 3 counties in north-central Liberia. Subsequently, qualitative, quantitative, and spatial analyses were done to explore gender and place-based differences in farmer access to agricultural resources and household agency.

Findings

Study results show that women farmers have less access to technology, agricultural resources and information; higher, combined productive and domestic, labor burdens; and that farmers of both genders want more female extension officers.

Practical Implications

This study provides critical data to help effectively target limited expenditures on national extension services to smallholder farmers in post-conflict settings. Further, solutions for practitioners to adaptively mitigate farming challenges enhanced by climate change.

Theoretical Implications

Studying the intersection among gender, rural isolation and diminished capacity in post-conflict countries will enhance understanding of (extension service) capacity in settings with multiple drivers affecting gender inequalities.

Originality

Improve the overall understanding of how compounding factors such as gender and place effect extension service access and the ability of farmers to adapt to change, in Liberia and other post-conflict settings.

Introduction

To varying extents across the globe agricultural extension (and advisory) services have become a staple mechanism for government and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to distribute resources, share relevant science and technology advancements, and engage in knowledge exchange with farmers to enhance agricultural productivity and technology adoption. At the core of extension are efforts, by both developing and developed nations, to close the gap between science and technology innovation for agriculture and its application (Jones and Garforth Citation1997). Over time, extension services have morphed from primarily top-down approaches to bottom-up information sharing, research and development, and sources of technological innovation for local problem solving (Rogers Citation1993). Despite efforts to increase the efficacy and equity of extension service dissemination to disenfranchized communities worldwide, women remain severely underserved in extension services across the globe (Coulter et al. Citation2019; Farnworth and Colverson Citation2015; Huyer Citation2016; Moore Citation2017; Quisumbing and Pandolfelli Citation2010).

Farmers play varied and vital social, economic, political, and environmental roles in their communities. In developing countries, agriculture is particularly critical for rural livelihoods and national food security. The agricultural sector is also intertwined with cultural gender norms, such as what women and men cultivate and who has access to the resources and power to make household agricultural decisions (Huyer Citation2016). Governments, via local agricultural extension services, may more effectively target the needs of farmers while simultaneously addressing cultural gender inequalities by understanding the needs of farmers through a holistic, intersectional lens.

In addition to having ample resources and highly trained personnel, the ability of governments to provide critical resources and information to farmers via local agricultural extension educators requires understanding the specific needs of farmers. However, farmers’ needs are not static, they often vary both demographically and geographically. Supporting farmers through siloed approaches is therefore ineffective. This paper integrates gender constructs and rural-urban linkages, specifically, how farmer agencyFootnote1 and access vary across and within gender and place. We also incorporate the concept of intersectionality (Crenshaw Citation1991) to explore the gender-place intersection as access limiting to rural Liberian farmers. Previous studies have used intersectional analysis to more holistically understand gender and agricultural development, and to provide suggestions for building farmer resilience in the face of change.

For example, Tavenner and Crane’s (Citation2019) study of Tanzanian dairy farmers showed the value of applying intersectionality analysis to differentiate the needs of women famers across social positionality and power scales. Through this approach they uncovered hidden social groups and power dynamics within agricultural systems, findings that may help development and extension practitioners to more effectively target farmer needs and build resilience rooted in local contexts. Further, Lawson et al. (Citation2020) explored the intersection of women farmers’ perceptions and climate change adaptation strategies in Ghana. Their study uncovered intra-gender differences critical to effectively target climate adaption policy, specific to women farmers. Similarly, a holistic understanding of the needs and challenges of Liberian farmers requires investigating the social and physical milieus in which they are shaped.

In post-conflict settings such as Liberia, that rely heavily on rural subsistence agriculture for national food security, employment, and gross domestic product, the roles of both women and men smallholder farmers are of critical value. In Liberia, 70% of the workforce derives a portion of their income from agricultural activities (Moore Citation2017) and up to 60% of productive agricultural labor in sub-Saharan Africa is conducted by women (Agarwal Citation2010; Ogunlela and Mukhtar Citation2009). While studies to date don’t specify a direct correlation or causation, social conflict may influence farmer demographics due to displacement, and disproportionate losses and injuries to young men that result in even higher proportions of women in agricultural production (Gbowee Citation2011; Tripp Citation2015). Therefore, understanding and addressing the needs of women farmers in rural agrarian communities is vital, especially in post-conflict countries.

This paper specifically investigates the intersection of gender, place in relation to rural isolation, and agricultural extension service access in north-central Liberia. The main aims were to understand 1) gender gaps in farmer agency and access to government provided extension services, 2) how rural isolation impacts farmer agency and access, and 3) how difference in agency and/or access may exacerbate the ability of farming communities to adapt to or resist social and environmental change in the Liberian study area, specifically in relation to women farmers.

Conceptualizing integration of gender constructs and place

The sections that follow are focused on understanding gender through the conceptual development of gender constructs and the meaning of place, including the impact of rural isolation on farmers. Additionally, we examine intersections of gender constructs and places specific to farmers’ access to resources and agency to use them. Finally, we highlight the intersection of gender and place in Liberia and suggest that climate stress will exacerbate this intersection and the need to address it through targeted extension services to rural women farmers.

Gender constructs

The concept of gender can take on multiple meanings that often cause controversy and confusion. The terms sex and gender are distinct yet interconnected. Distinguished from ‘sex’, the biological characteristics that differentiate females from males (Reeves and Baden Citation2000), ‘gender’ denotes what it means to be a woman (feminine) or man (masculine) through social and cultural distinctions such as behavior, social roles, position, or identity (Reeves and Baden Citation2000; Maguire Citation2006). Gender is a construct used to separate people into distinct categories, it is not a trait (Ferree and Hess Citation1987). Diverging from the sole biological characteristics referred to by sex, this paper uses the stated definition of gender to understand the differences between women and men in relation to their abilities to gain access to agricultural resources and information and exert agency in their households. An aspect of this gap relates to social and cultural gender norms that relegate women in agriculture to subsistence farming for household nutrition or as farm helpers, and men to productive laborers (Huyer Citation2016; Kevane Citation2012).

The Swedish historian Yvonne Hirdman (Citation1991) uses gender systems theory to clarify that gender has historically implied difference, and ‘is a complicated process by which people are shaped to fit their gender, and the consequences this has in institutional, cultural and indeed even biological terms’ (190). Gender systems theory explicitly acknowledges power relationships that exist between the genders and the role of power in maintaining the subordination of women, and gender separation (Rantalaiho et al. Citation1997; Hirdman Citation1991).

Hirdman (Citation1991) refers to these as the two principles of ‘difference’ and ‘hierarchy’ explicit in gender systems. Framing the gender construct through a systems lens provides a more dynamic representation of the complex set of relations, ideas, and processes that shape how gender is interpreted and manifested (Rantalaiho et al. Citation1997). The definition of gender varies with context (i.e. spatially and temporally). This dynamic nature is more fully captured by the idea of local gender contracts. Despite the use of the term ‘contract,’ gender contract denotes a system that may include substantial power differentials and may be imposed by societal norms rather than voluntary agreement among the different genders or among individuals (Duncan Citation2000).

Gender contracts are place-based, informally organized gender relations. They define a pervasive system or set of norms that describe the appropriate or accepted actions and interactions of women (feminine) and men (masculine) in a given place at a given time (Hirdman Citation1991). Gender systems are operationalized through local gender contracts under specific circumstances. Local gender contracts have been used as a framework to describe overlapping gendered and geographic relationships and power divides in the everyday lives of women and men. For example, the gender and age specific practices of rubber tappers in Laos are described through geographic differences as related to divisions of labor in the public and private spheres (Lindeborg Citation2012); the societal roles of and equality for Swedish women inside and outside of the home (Duncan and Pfau-Effinger Citation2012; Forsberg and Stenbacka Citation2013); and through the negotiation of gender roles during a self-help housing project in Lobatse, Botswana (Kalabamu Citation2005). Whereas women are often responsible for constructing homes in rural Botswana, men are contracted to build in urban communities. Kalabamu’s (Citation2005) case study shows local gender contracts in the urban city of Lobatse initially constrained, and then further compromised, the ability of women to exert agency in a self-help housing project in this low-income urban neighborhood. Patriarchal traditions across Africa par excellence may continue to shape local gender contracts that subordinate and marginalize women or, through transformation, be used to uplift them. Despite the persistent and hierarchical nature of the social relations formed and sustained through gender contracts, they are not static. This idea provides the prospect of renegotiation and transformation for local gender contracts (Hirdman Citation1991; Kalabamu Citation2005).

Hirdman (Citation1991) describes a transition from the ‘housewife contract’ to a ‘contract of equality’ in Sweden during the period of 1930–1975, while Caretta and Börjeson (Citation2015) show further evidence for gender contract renegotiation through a case study in Sibou, Kenya. They suggest that climate variability influences the transformation of two gender contracts they call the ‘local resource contract’ and the ‘household income contract.’ The study shows that in order to build community adaptive capacity in the face of climate variability, women and men adapt differently in relation to their specific gender roles for agriculture and irrigation. Changes include the cultivation of cash crops by men leading to women adopting historically male roles like fencing, herding, and intercropping (Caretta and Börjeson Citation2015). In the face of change (physical or social), Caretta and Börjeson (Citation2015) contend that more effective and gender sensitive climate change adaptation policies will rely on understanding the negotiation and transformation of local gender contracts. We suggest the same might be true for the relationship between agricultural extension service provisioning and local gender norms or contracts in north-central Liberia where this study is set.

Place and rural isolation

Gender is socially constructed and cannot be removed from place and time; it is always rooted in individual human or collective social experiences. We refer to places as more than just differentiated physical locations. Places are unique, meaningful constructions that reflect and shape cultural and social habits and perceptions, including those pertaining to gender. Thus, rural places as the setting for local gender contracts is important to consider when exploring farmer access and agency in north-central Liberia.

A quarter of Liberia’s population lives in Monrovia proper combined with the outlying peri-urban settlements. In the context of this study, extension resources and information primarily originate from the Liberian Ministry of Agriculture in Monrovia and are disseminated via regional District Agricultural OfficersFootnote2 (DAO) in rural communities. Therefore, understanding the connections within and between urban and rural areas including power hierarchies and decision-making has an impact on the process of extension efficacy and how that relates to building food security and gender equality.

Rural-urban linkages

We see the rural-urban linkages framework as a conceptual approach to help account for rural isolation through the incorporation of place distinctions; specifically, by considering how agricultural resource and information access, farming productivity, and agency vary across the study communities via a rural to urban spectrum. To help distinguish rural vs urban, Tacoli (Citation2006, 4) references governmental designations by population size thresholds alone, or in combination with other criteria (e.g., local employment, access to electricity), through administrative or political boundaries, or national census data settlement lists (Tacoli Citation1998, Citation2003; Yerian et al. Citation2014). Despite such efforts, Satterthwaite and Tacoli (Citation2006) conclude that while these designations remain pertinent to resource allocation, they have significant variation and global ambiguity. For the purposes of this study, we use the Liberian designation for rural as a community with less than 2000 people (Perry Citation2017).

Rural isolation is of particular concern in Libera, specifically for farmer productivity and gender equity in subsistence farming communities. Rural isolation is exacerbated in post-conflict settings due to limited infrastructure and social services that threaten the capacity of already vulnerable communities to meet their financial and nutrition needs. Perez et al. (Citation2015) found that women are more vulnerable to rural isolation due to their tendency to have internal community networks while men are more likely to have networks outside of their communities. This finding is corroborated by Cohen et al. (Citation2016) who showed that women and children in their study were less likely to access information through established relations with external agencies when compared to men. Further, as evidenced in Liberia (Moore Citation2017), rural isolation limits the reach and efficacy of extension officers. Living in rural communities compounds the inadequate access and use of vital agricultural resources and information of women farmers.

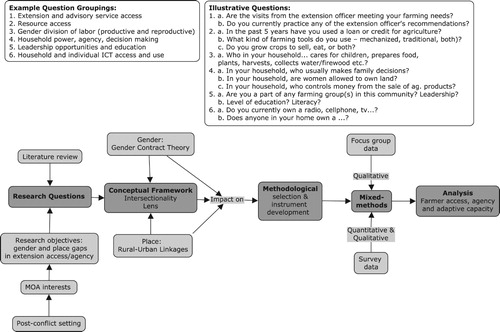

Rural isolation, influenced by rural-urban linkages, is inherently place-based. Therefore, it is useful to consider gender contracts within the distinct context of rural isolated places, particularly the roles that gender contracts play in women’s access to and agency involving agricultural resources and information. This study combines these concepts through an intersectionality lens to understand where gender and place may intersect to further discriminate against women farmers in certain communities. The analysis that follows is guided by this overarching conceptual framework to understand extension access and agency through intersectional, place-based, gender contracts ().

Methods

Study site

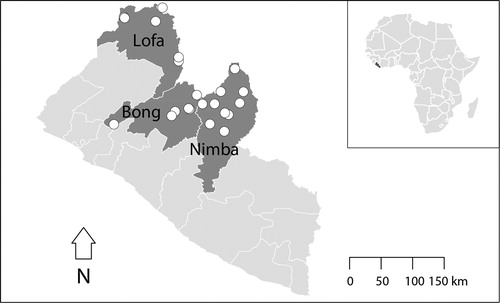

Situated on the west coast of sub-Saharan Africa, our study site in north-central Liberia encompasses three counties and 22 communities that are known for their agricultural productivity (primarily subsistence) (Moore Citation2017; Perry Citation2017). The communities are ethnically, religiously, and economically diverse, and mostly rural (14 communities had less-than 2000 people). The study area was central to fighting during the Liberian civil wars (1989–2003) and provided an artery for transmission of the Ebola virus (2015) (Gbowee Citation2011; Moore Citation2017) .

Data collection and analysis

Data collection took place between February 1–28, 2018. Study instruments included a 200-question mixed-methods survey and a 20-question focus group guide. Both were developed and administered using SurveyCTO software. A collective, multisite case study methodology was used to frame this study (Creswell and Poth Citation2016; Yin Citation1994; Zainal Citation2007). Three counties were pre-selected by in-country partners due to their productivity and distinction as Liberia’s breadbasket. From those counties, 24 communities (Bong 7, Nimba 11, and Lofa 6) were selected purposefully and using sampling techniques (Newing Citation2010); of those, we conducted focus groups and surveys in 22 communities. Communities were chosen based on specific criteria (Appendix A) provided by researchers through a participatory mapping exercise with District and County extension staff from the three focal counties. Selected communities fell between the rural-urban delineations, with the majority being considered rural (<2000); this strategy was used due to a lack of census data. The large physical area covered during data collection helped to increase the diversity of farmer experiences with agricultural and advisory services. An equal number of women and men participated in the 352 surveys administered by project-trained Cuttington University student enumerators in 22 communities (16 farmers per community). An additional 44 gender-disaggregatedFootnote3 focus groups (two per community) were conducted by the two lead researchers. Eight hundred and eleven farmers (417 women, 394 men) participated in focus groups across the study area.

In each community, the DAO, a local elder or farmer group representative, and farmers welcomed our team. The day always commenced with prayer and full introductions. Then, 16 farmers were randomly selected using what we called a paper game. This included farmers self-selecting by gender and then choosing a piece of paper from a hat brought around by the students; of the papers, 16 had an X written on it (8 for women and 8 for men) and farmers that selected these papers were individually surveyed. Survey and focus group respondents were over the age of 18 and self-identified as farmers based on their production of food, livestock, or their role as farm laborers. Daily, we gave a financial contribution for the community lunch and local translators who volunteered, those present contributed rice and prepared the meal.

During survey and focus group data collection, participants were asked questions about their use of information and communication technology (ICT), preference for the gender of their extension officers, access to extension services, etc. Groups of questions were developed by the research team targeting context specific research objectives set out in collaboration with and in response to goals of the Liberian Ministry of Agriculture. The results section subheadings reflect these pre-defined question groupings while the thematic codes specified under each subheading were inductive. Focus groups and open-ended survey questions were coded and descriptively analyzed using the computer assisted qualitative and mixed-methods data analysis software MAXQDA. Two researchers coded qualitative data to identify emergent themes. Quantitative analysis was conducted in SPSS and R Studio and is further explored in a subsequent manuscript (in review).

Results

Participant demographic characteristics

Demographic characteristics of the survey participants (n = 352) are summarized in and . The vast majority (98%) identified with one of six ethnic groups and responded that they were Christian (90%). Sixty-nine percent of the participants were between the ages of 25 and 54 years old, 81% were married or lived with a partner, and 80% of those that listed themselves as holding the position of household head were men. Just over half of the participants (52%) reported that they had no formal education or only elementary school. Women were more likely to have completed junior high school or below (43%, n = 150) when compared to men (25%, n = 89). However, a higher percentage of men completed high school through university classes (24%, n = 87) when compared to women (7%, n = 26); only 16% of the 51% of literate participants were women.

Table 1. Participant Demographic Characteristics

Table 2. Participant level of education, relationship status, and age by gender

Information and communication technology access

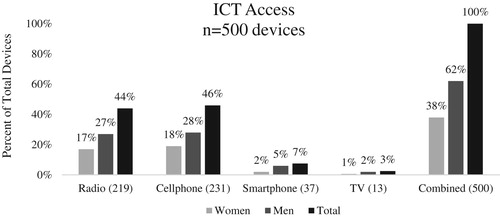

Three hundred and fifty-two farmers reported personal or household access to one or more ICT devices, resulting in 352 farmers with access to 500 total devices (). Of them, women were 24% less likely to have access to ICT devices for gaining and sharing information about agriculture (). Farmers described ‘ownership’ barriers to ICT access such as ‘it [the phone] is for me and I keep it in my room’ or ‘everyone has his or her less basic time to listen to the radio or use the cellphone.’ Additional gender specific barriers were expressed by women who stated the radio ‘is for the man in the home’ and ‘the gadgets are controlled by my husband.’ Further, out of 352 participants only women reflected technical skills as a barrier to ICT access as reflected by participant 277: ‘I can only receive call and don’t know how to make calls.’ Qualitative quotes also showed that ICT access for certain groups of people was limited due to the need for responsible adults to care for the devices or the cost to maintain them reflected by participant 297: ‘ … I use it [the cellphone] to access information and I also spend money to purchase battery. Due to this, if everyone uses it the way I use it, it means there are surplus batteries which is not possible.’

Figure 3. Access to ICT devices. Note: Values represent the percent of total devices owned by 352 participants; multiple devices could be selected.

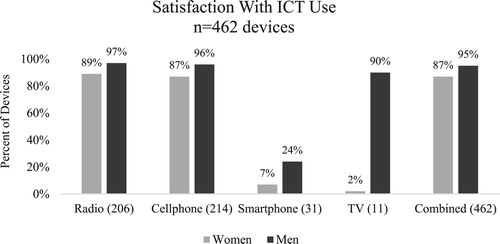

Gender differences in farmers’ satisfaction with ICT device use were also noted through descriptive quantitative results. In , respondent satisfaction of device use is calculated as a percent of total access by farmer gender shown in . Women respondents were satisfied with their use, i.e. time spent on the device, 87% of the time in comparison to men at 95% (). When combined with the descriptive survey results, qualitative data from focus groups and open-ended survey questions substantiated the findings that while many farmers had less than adequate access to technology, men had greater access and were more satisfied with their use than women farmers (also see supplemental material).

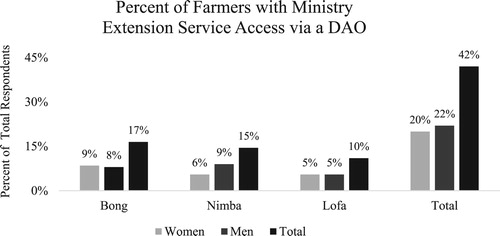

Access to extension services

Survey results reflected limited extension service access across all three counties for both women and men farmers with only 42% (148 farmers) reporting Ministry extension access via a DAO in the past three years. However, when viewed by county, Lofa farmers had the lowest amount of access (10%) in comparison to Bong (17%) and Nimba (15%) (). Using an analysis of variance test, we confirmed that this access gap between Lofa on the one hand and Bong and Nimba on the other was statistically significant (p = .001). Additionally, Lofa reported lower total extension service access when compared to Bong or Nimba while Nimba exhibited the largest gap in access between women and men (). On this basis, we investigated for other possible differences across counties. While we found that overall men had significantly larger farms (p = .01) and spent more on agricultural information (p = .001), these did not vary significantly by county. Overall, 189 farmers (54%) reported to have worked with an NGO, and 99 farmers (28%) received both Ministry and NGO extension services.

Figure 5. Percent of all respondents by county (n = 352) with access to Ministry extension services via a DAO in the past three years. Note: Total is the sum of women and men for each county and overall

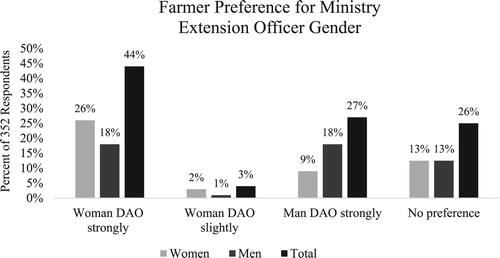

Farmer preference for ministry extension officer gender

shows that a plurality of farmers (women and men) reported wanting more women extension officers to serve them and their communities. Collectively, 44% of farmers would strongly prefer that a woman DAO serve them, two-thirds of whom were women. The same percent of men strongly prefer a woman or strongly prefer a man DAO, and 27% of all farmers would strongly prefer a man DAO. Twenty-six percent of women and men have no preference for the gender of their DAO.

Figure 6. Respondent gender preference for Liberian extension officers. Note: Total is the sum of women and men for each response, n = 352

Illustrative quotes from the focus group and open-ended survey questions can help to explain why farmers express these preferences (also see supplemental material). For example, one male participant noted that he would prefer a woman extension officer work with him in the future ‘ … because agriculture is like training a child or nurturing a child. This applies to growing crops.’ Another suggested that women are more trustworthy when he said, ‘I think that women are not corrupt to sell fertilizers to farmers. Most women are transparent.’ Several female participants alluded to the fact that they identify more with women farmers: ‘women are aware of the challenges in the home and in the field.’

Common themes highlighted by the 27% of farmers who preferred a male extension officer were their physical strength, ‘ … I feel they [men] are strong and able to walk in the bush with us,’ and religious references such as ‘ … because I don’t want woman control me. Because we are superior to them, they are our ribs.’ Another 26% of farmers shared that qualifications are their only requirement, not gender. Specific quotes reflect that ‘women are now going to school so they can do the same men can do’ including be an extension officer. Additionally, that the ‘ … Ministry [of Agriculture] is responsible to send extension agent who I think will be qualified.’ Gender equality and geographic limitations were also highlighted by participants.

Opportunities to improve extension impact

Qualitative quotes corroborate the quantitative findings that improving access to agricultural resources and training opportunities is vital for farmers to overcome stated challenges and increase productivity and food security. Farmers highlight specific access limitations and recommendations for the Ministry and its field staff. One participant asked for the Ministry to ‘train and utilize local technicians’ while another suggested that farmers’ needs are place specific and extension officers should ‘know where specific crops grow and send technicians where they know best or what they know best.’ Farmers also highlighted the need for improved access to loans and markets, in addition to monitoring and accountability for both Ministry extension providers and development projects. For example, ‘the government is not monitoring if their work is creating impacts and getting to who is meant to get it’ and another that ‘there is poor communication between DAO/Ministry and farmers and NGOs.’

Farmer insights about gendered roles

Ideas about connection between food security and local community security came out in the focus groups. The acknowledgment of women’s contributions around food preparation and money management in households and the farming community was expressed. For example, ‘No country will grow without food, without food security there is insecurity.’

Participants acknowledged women’s contributions and dual burdens. One farmer stated that ‘sometime some man will leave the work on the woman. After doing the hard work, we are also responsible for the children’ and another that ‘women do 60% [of the total household work] because they cater to the home and have work on the farms.’ One farmer highlighted the holistic nature of farming by suggesting ‘ … before, the population was not much, but now due to the [population] increase land issue is becoming the problem [for farmers].’ Both women and men farmers also stressed the need for more training (agricultural and otherwise) and empowerment in their communities. Lastly, through informal interactions during data collection we frequently heard mention of more recent government efforts to sensitize communities on the legal rights of women to inherit and own land.

Discussion and conclusions

Many smallholder farmers have less than sufficient access to extension resources and information or to information specific to their context, while Liberia is lacking overall in the resources to hire, train, and disseminate an adequate number of DAOs to over one million farmers nationally. Our study provides evidence that within the strained national systems, differences in local gender contracts impact the ability of farmers to access agricultural resources/information and utilize them, and that this is often specific to farmers’ gender and community.

However, farmers of both genders supported increasing the number of women extension officers, previously found to help close gender gaps in information exchange and technology adoption for women farmers. For example, Kondylis et al. (Citation2016) explored the potential to reduce gender bias in extension service dissemination through employing more women extension officers in Mozambique. They found an increase in women farmers’ demand for and access to information when it was disseminated by a trained female extension provider as opposed to a male provider. Further, the study found an increase in male extension providers’ motivation in the presence of female providers, potentially increasing the outreach to all farmers regardless of their gender.

Similar to earlier studies, we found that women farmers are more marginalized when compared to their male counterparts, with lower access to ICT devices, education, and associated agricultural resources that relate to their gender contracts (i.e., daily roles and responsibilities) (Perez et al. Citation2015). However, these findings should not be understood as immutable outcomes but rather how gendered contracts have unfolded over time in these communities due to a variety of other factors. Further, these local gender contracts have the potential to change over time and the national extension policies can play a role in influencing and transforming local outcomes of gender norms and systemic power structures. For instance, extension providers can train and promote women in specific communities in techniques of cash crop production, help to build women’s business and marketing competencies, and educate women on their legal right to own land. These recommendations draw from our contention that gender contracts are influenced by intersectional factors specific to place. Therefore, looking at gender and place through an intersectional lens is an important contribution.

Previous studies suggest that place influences agricultural productivity, what farmers need to be successful, and their access to resources (Grover and Gruver Citation2017). Post-conflict countries face additional challenges related to place, such as restricted access due to limited infrastructure, outmigration, mortality of young men, and detrimental gender norms (Tacoli and Mabala Citation2010; Tripp Citation2015). On these and related issues, looking at place or gender in isolation presents a partial lens that intersectionality helps account for in this case study (Rodo-de-Zarate and Baylina Citation2018). Gender-specific and place-targeted extension service practices are vital to Liberian smallholder farmers. Unfortunately, the uncertainties of funding and primarily older male personnel are not currently meeting farmers’ needs. Therefore, realizing what stands in the way of all farmers accessing agricultural resources and making decisions, regardless of gender or geography, is critical for extension officers to fully support agricultural productivity. Study results show significant differences in household power dynamics and resource access of farmers based on gender. In light of the Ministry’s gender initiatives, these results demonstrate potential for extension services to be used as a catalyst for the transformation of local gender contracts toward greater gender equity.

Gender contracts

Extension officer gender

An important discovery of our study is that farmers collectively support increasing the number of women extension officers. In fact, respondents of both genders report that they prefer for women extension officers to serve them and their communities. At the root of these sentiments are women’s increased access to education, farmers' frustration with their current male agents, and Liberia’s recent promotion of and legal stance on gender equality. However, cultural beliefs that women should hold lower rankings in society and stereotypes that men are more suited for extension work because of their physical strength remain possible deterrents to the acceptance of women extension officers by men farmers. Further, the training of local technicians and increased support for farmer-based organizations and entrepreneurial opportunities, especially for women, will require consistent knowledge sharing that may be further facilitated by increased technology access.

Land inheritance contract

Anecdotally, while in the field, our team members often heard from community members that they were aware of women’s legal rights to inherit and own land; however, women in many surveyed communities still cannot effectively exert those rights due to cultural, religious, and social barriers. Such beliefs and informal laws reinforce an inequitable patrilineal ‘land inheritance contract’ that favors sons over daughters for land allocation. Both formal and informal structures in the study area continue to limit women’s land ownership when compared to men. Extension officers can help transform this contract by increasing community sensitization to the national legal rights of Liberian women and girls to own and inherit land and access education. Also, extension officers can support women, as well as men, to diversify their crops and save seeds, develop local organic pesticides/fertilizers, and build business skills to open new economic opportunities.

Place and rural isolation

From the results, it can be inferred that extension officers have the ability to leverage local social capital — making place germane due to the extremely disproportionate number of farmers to national extension officers combined with degraded infrastructure and varied farmer access to ICT.

Our survey results corroborate other studies that show how the marginalization of women in relation to agricultural extension service access and employment remains evident in both developing and developed countries (Huyer Citation2016; Trauger et al. Citation2008). Spatial variation in farmer access to ICT devices and extension services indicates that both the needs of farmers and extension capacity may be impacted by geographic isolation; further confirming that the Ministry of Agriculture field staff struggle to cover large territories under visibly difficult conditions with stated resources limitations (Moore Citation2017; Talery-Wiles Citation2012). Rural isolation also comes to bear in farmers’ limited access to stable markets, local banks and therefore credit, employment opportunities, and vital agricultural information and resources. In fact, the lack of sufficient education and employment opportunities in many rural areas has led to an outmigration of able workers, especially young men.

To combat rural isolation and poor infrastructure, the Ministry and other organizations providing agricultural support can capitalize on the use of ICT to increase communication with existing farmer-based organizations, develop new ones, and train extension technicians, all at the local level. Overall, ICT findings allude to the potential role of technology in extension education and concur with studies that suggest ICT can help combat geographic isolation and build community resilience (Perez et al. Citation2015; Zewdu and Malek Citation2010).

Information and communication technology

With urbanization leading to male outmigration (Tacoli Citation1998, Citation2003; Zewdu and Malek Citation2010) and other shifts in agricultural systems on the rise, it’s becoming more important to prepare women for technology advancements related to agricultural production and knowledge sharing (Quisumbing and Pandolfelli Citation2010; Huyer Citation2016). Quisumbing and Pandolfelli (Citation2010) highlight the potential behind technology for women as a tool for information sharing and to decrease women’s labor burdens (i.e., time allocation) in developing countries. Engaging farmers with technology may also provide an avenue to occupy the high number of unemployed youths in Liberia and other post-conflict countries (Scarborough Citation2017). Increasing women’s ICT capabilities may also enrich their external networks, which could lead to improved resilience via broadened support systems, and more diverse knowledge exchange and economic inputs (Perez et al. Citation2015). In order to enhance ICT capabilities, barriers to the exercise of household agency (i.e., power and decision-making) by women must also be addressed.

Financial strain and household power dynamics contribute to the insufficient access and use of ICT devices by both genders across the study area ( and ). However, women are less likely to be satisfied with their ICT access/use and are further constrained by higher illiteracy rates and less household power and free time. Technology infrastructure and literacy for agricultural information sharing with and between farmers would be a wise investment for the Ministry and NGOs alike. Moreover, it will be especially beneficial to target geographically isolated communities. ICT capacity building must be coupled with literacy, leadership, and business training for women.

Moving forward

With a more integrated approach, extension services have the potential to build community resilience in the face of natural disasters and disease epidemics on the rise due to climate change. Further research in this area should engage more with resilience literature. It has been shown that low-income countries will be disproportionately impacted by the climate crisis, and of those affected, women are likely to suffer the most (Farnworth and Colverson Citation2015; Perez et al. Citation2015). Therefore, it is important to understand the role of gender in agricultural production and resilience, and further, to acknowledge that the ability of farmers to be resilient, especially women, is and will continue to be compounded by the climate crisis. Climate change impacts vary geographically and, while future predictions acknowledge uncertainty, there is a general consensus that sub-Saharan Africa will be forced to grapple with increased natural disasters, both flooding and drought, and changes in temperature that may exacerbate pest outbreaks (Stanturf et al. Citation2013, Citation2015).

Accordingly, extension officers and systems play a critical role in improving the production potential of farmers and food security of nations. This study showed that they can influence women’s access to agricultural resources and improve community resilience when effectively targeted to local needs. Thus, understanding agricultural systems at the intersections of gender and place – through a local gender contracts lens – with extension services, is an important theoretical implication of this study and reinforces the need to support farmers at the local level. Theoretically speaking, we also see evidence of where gender contracts are maintained rigidly and where they seem to be malleable to change. Practically speaking, identifying the role of extension to improve food security and build farmers’ capacity in the face of change is even more critical in post-conflict settings where resources and data availability are limited, and systems are taxed.

Moving forward, we recommend that policy makers acknowledge that hiring more women extension officers can play a role in decreasing the gender gap in extension support. Additional suggestions for policy and decision makers are to a) target farmer specific geographic and demographic needs; b) train more local technicians and improve the capacity of community liaisons, especially women; c) more effectively use technology (i.e., radios, cellphones) for communication and knowledge sharing; d) work with community-based women’s farmer groups and establish them in communities where they don’t already exist; and e) partner with national academic and research institutions to engage the next generation of extension professionals. Lastly, in developing countries women remain at the fore of domestic labor and food production, and it is high time that national governments understand and account for their unique contributions to both.

Survey_Instrument.pdf

Download PDF (287.5 KB)supplemental_qualquotes.pdf

Download PDF (413.8 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Barbara Cosens and Janet Henderson for their feedback during development of study protocols, data analysis, and writing. We would also like to thank Cuttington University and the Liberian Ministry of Agriculture for their partnership on this project. Lastly, the University of Idaho Water Resources Graduate Program for collaboration and research support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rebecca Witinok-Huber

Rebecca Witinok-Huber is an environmental social scientist. Her work emphasizes intersectionality across disciplines, and focsus on gender, environmental health, agriculture, natural resource management, climate adaptation, and rural-urban connection. .

Steven Radil

Steven Radil is a political geographer and his research examines geographical dimensions of international and domestic politics. He is interested in the spatialities of political violence; the geographical spread of armed conflicts; and the issues involved in using geospatial technology to explore political topics.

Dilshani Sarathchandra

Dilshani Sarathchandra is an associate professor of sociology at the University of Idaho. Her research focuses on decision-making processes in science, public attitudes toward science and technology, and social dimensions of health.

Caroline Nyaplue-Daywhea

Caroline Nyaplue-Daywhea is a lecturer at Cuttington University with extensive practical experience in agricultural education. Her work focuses on improving farmer access to agricultural extension services, food security, gender equity, and inclusive pedagogy.

Notes

1 Agency is a process by which an individual or group is able to define their goals and act on them (Kabeer, Citation2005), it is closely related to power and decision-making.

2 In Liberia, field-based extension providers are called District Agricultural Officers (DAO). While the terms agent (global south) and educator (global north) may be used synonymously with officer depending on the regional context, we refer to professionals providing extension services as extension officer throughout the manuscript.

3 The collection of data based on community and/or self-identified gender division of participants.

References

- Agarwal, Bina. 2010. “Does Women’s Proportional Strength Affect Their Participation? Governing Local Forests in South Asia.” World Development 38 (1): 98–112.

- Caretta, Martina Angela, and Lowe Börjeson. 2015. “Local Gender Contract and Adaptive Capacity in Smallholder Irrigation Farming: A Case Study from the Kenyan Drylands.” Gender, Place and Culture 22 (5): 644–661. doi:10.1080/0966369X.2014.885888.

- Cohen, Philippa J, Sarah Lawless, Michelle Dyer, Miranda Morgan, Enly Saeni, Helen Teioli, and Paula Kantor. 2016. Understanding adaptive capacity and capacity to innovate in social-ecological systems: Applying a gender lens. Ambio 45 (3): 309–321.

- Coulter, Janna E., Rebecca A. Witinok-Huber, Brett L Bruyere, and Wanja Dorothy Nyingi. 2019. “Giving Women a Voice on Decision-Making about Water: Barriers and Opportunities in Laikipia, Kenya.” Gender, Place and Culture 26 (4): 489–509. doi:10.1080/0966369X.2018.1502163.

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 1991. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review 43 (6): 1241–1299. doi:10.2307/1229039.

- Creswell, John W., and Cheryl N. Poth. 2016. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Sage Publications.

- Duncan, Simon. 2000. “Theorising Comparative Gender Inequality in Duncan S and Pfau-Effinger B eds Gender, Economy and Culture in the European Union Routledge.” London 1: 24.

- Duncan, Simon, and Birgit Pfau-Effinger. 2012. Gender, Economy and Culture in the European Union. London and New York: Routledge.

- Farnworth, Cathy Rozel, and Kathleen Earl Colverson. 2015. “Building a Gender-Transformative Extension and Advisory Facilitation System in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Journal of Gender, Agriculture and Food Security (Agri-Gender) 1 (1): 20-39.

- Ferree, Myra Marx, and Beth B. Hess. 1987. Analyzing Gender: A Handbook of Social Science Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Forsberg, Gunnel, and Susanne Stenbacka. 2013. “Mapping Gendered Ruralities.” European Countryside 5 (1): 1–20. doi:10.2478/euco-2013-0001.

- Gbowee, Leymah. 2011. Mighty be our Powers: How Sisterhood, Prayer, and sex Changed a Nation at war. New York: Beast Books.

- Grover, Samantha, and Joshua Gruver. 2017. “Slow to Change’: Farmers’ Perceptions of Place-Based Barriers to Sustainable Agriculture.” Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 32 (6): 511–523.

- Hirdman, Yvonne. 1991. “‘The Gender System’.” In Moving on: New Perspectives on the Women's Movement, edited by T. Andreasen, et al. Arhus: Arhus University Press, 187–208.

- Huyer, Sophia. 2016. “Closing the Gender Gap in Agriculture.” Gender, Technology and Development 20 (2): 105–116. doi:10.1177/0971852416643872.

- Jones, Gwyne E., and Chris Garforth. 1997. “Chapter 1-The History, Development, and Future of Agricultural Extension.” In Improving Agricultural Extension: A Reference Manual, edited by Burton E. Swanson, Robert P. Bentz, and Andrew J. Sofranko, 1–32. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Kabeer, Naila. 2005. “Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the Measurement of Women's Empowerment.” Development and Change 30 (3): 435–464.

- Kalabamu, Faustin. 2005. “Changing Gender Contracts in Self-Help Housing Construction in Botswana: The Case of Lobatse.” Habitat International 29 (2): 245–268.

- Kevane, Michael. 2012. “Gendered Production and Consumption in Rural Africa.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109 (31): 12350–12355.

- Kondylis, Florence, Valerie Mueller, Glenn Sheriff, and Siyao Zhu. 2016. “Do Female Instructors Reduce Gender Bias in Diffusion of Sustainable Land Management Techniques? Experimental Evidence from Mozambique.” World Development 78: 436–449.

- Lawson, Elaine T, Rahinatu Sidiki Alare, Abdul Rauf Zanya Salifu, and Mary Thompson-Hall. 2020. “Dealing with Climate Change in Semi-Arid Ghana: Understanding Intersectional Perceptions and Adaptation Strategies of Women Farmers.” GeoJournal 85 (2): 439–452.

- Lindeborg, Anna-Klara. 2012. “Where Gendered Spaces Bend: The Rubber Phenomenon in Northern Laos.” PhD diss., Kulturgeografiska institutionen, Uppsala universitet.

- Maguire, Patricia.. 2006. “Uneven Ground: Feminisms and Action Research.” In Handbook of Action Research, edited by Peter Reason and Hilary Bradbury, 60–70. London, Thousand Oaks and New Delh: Sage Publications.

- Moore, Austen. 2017. “Agricultural Extension in Post-conflict Liberia: Progress made and Lessons Learned.” Chap. 1 in Agricultural Extension in Post-Conflict Liberia: Progress Made and Lessons Learned, edited by Paul McNamara and Austen Moore. Wallingford: CABI. doi:10.1079/9781786390592.0001.

- Newing, Helen. 2010. Conducting Research in Conservation: Social Science Methods and Practice. London and New York: Routledge.

- Ogunlela, Yemisi I., and Aisha A. Mukhtar. 2009. “Gender Issues in Agriculture and Rural Development in Nigeria: The Role of Women.” Humanity and Social Sciences Journal 4 (1): 19–30.

- Perez, Carlos, E. M. Jones, Patricia Kristjanson, Laura Cramer, Philip K. Thornton, Wiebke Förch, and C. A. Barahona. 2015. “How Resilient Are Farming Households and Communities to a Changing Climate in Africa? A Gender- Based Perspective.” Global Environmental Change 34 (September): 95–107. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.06.003.

- Perry, Edward. Interview by Rebecca Witinok-Huber. Informal Project Development and Extension Service Background Interview. Monrovia, Liberia, December 15, 2017.

- Quisumbing, Agnes R., and Lauren Pandolfelli. 2010. “Promising Approaches to Address the Needs of Poor Female Farmers: Resources, Constraints, and Interventions.” World Development 38 (4): 581–592. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.10.006.

- Rantalaiho, Liisa, Tuula Heiskanen, Päivi Korvajärvi, and Marja Vehviläinen. 1997. “Studying Gendered Practices.” In Gendered Practices in Working Life, edited by Liisa Rantalaiho and Tuula Heiskanen, 3–15. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Reeves, Hazel, and Sally Baden. 2000. “Gender and Development: Concepts and Definitions.” Accessed August 15, 2018. http://www.bridge.ids.ac.uk/sites/bridge.ids.ac.uk/files/reports/re55.pdf.

- Rodo-de-Zarate, Maria, and Maria Baylina. 2018. “Intersectionality in Feminist Geographies.” Gender, Place and Culture 25 (4): 547–553.

- Rogers, Alan. 1993. “Adult Education and Agricultural Extension: Some Comparisons.” International Journal of Lifelong Education 12 (3): 165–176.

- Satterthwaite, David, and Cecilia Tacoli. 2006. The Role of Small and Intermediate Urban Centres in Regional and Rural Development: Assumptions and Evidence.

- Scarborough, Gregory. 2017. “Growing a Future: Liberian Youth Reflect on Agriculture Livelihoods.” Mercy Corps. Accessed June 1, 2018. https://www.mercycorps.org/sites/default/files/2020-01/Liberian-Youth-Reflect-on-Agriculture-Livelihoods-Mercy-Corps-2017_0.pdf.

- Stanturf, John A., Scott L. Goodrick, Melvin L. Warren, Jr., Susan Charnley, and Christie M. Stegall. 2015. “Social Vulnerability and Ebola Virus Disease in Rural Liberia.” PLoS One 10 (9): e0137208. Accessed October 5, 2019. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0137208#sec001.

- Stanturf, John A., Scott L. Goodrick, Melvin L. Warren, Jr., Christie M. Stegall, and Marcus Williams. 2013. Liberia Climate Change Assessment. USAID, USDA Forest Service. Accessed August 10, 2019. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237102310_LIBERIA_CLIMATE_CHANGE AESSMENT.

- Tacoli, Cecilia. 1998. “Rural-Urban Interactions: A Guide to the Literature.” Environment and Urbanization 10 (1): 147–166.

- Tacoli, Cecilia. 2003. “The Links Between Urban and Rural Development.” Environmental and Urbanization 15 (1): 3–12. Accessed June 10, 2018. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/095624780301500111.

- Tacoli, Cecilia. 2006. The Earthscan Reader in Rural-Urban Linkages. London and New York: Routledge.

- Tacoli, Cecilia, and Richard Mabala. 2010. “Exploring Mobility and Migration in the Context of Rural— Urban Linkages: Why Gender and Generation Matter.” Environment and Urbanization 22 (2): 389–395. doi:10.1177/0956247810379935.

- Talery-Wiles, Tonieh A. 2012. Republic of Liberia Ministry of Agriculture: Strategy for mainstreaming gender issues in agriculture programs and projects in Liberia. Draft.

- Tavenner, K., and T. A. Crane. 2019. “Beyond “Women and Youth”: Applying Intersectionality in Agricultural Research for Development.” Outlook on Agriculture 48 (4): 316–325.

- Trauger, Amy, Carolyn Sachs, Mary Barbercheck, Nancy Ellen Kiernan, Kathy Brasier, and Jill Findeis. 2008. “Agricultural Education: Gender Identity and Knowledge Exchange.” Journal of Rural Studies 24 (4): 432–439. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2008.03.007.

- Tripp, Aili Mari. 2015. Women and Power in Post-Conflict Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Yerian, Sarah, Monique Hennink, Leslie E. Greene, Daniel Kiptugen, Jared Buri, and Matthew C. Freeman. 2014. “The Role of Women in Water Management and Conflict Resolution in Marsabit, Kenya.” Environmental Management 54 (6): 1320–1330.

- Yin, Robert. 1994. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. 2nd ed. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publishing.

- Zainal, Z. 2007. “Case Study as a Research Method.” Jurnal Kemanusiaan 5 (1): 1–6.

- Zewdu, Getnet Alemu, and Mehrab Malek. 2010. “Implications of Land Policies for Rural-Urban Linkages and Rural Transformation in Ethiopia.” Development Strategy and Governance Division, International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). Ethiopia Strategy Support Program 2: 20006–21002.

Appendix A: Community Selection Criteria

You (Liberian District Agricultural Officer) have worked in this community and feel good about the work you’ve done.

There are women and men farmers in this community.

Farmers in this community are diverse ages. (18 to …)

Farmers in this community have different income levels or livelihoods and have different farm sizes (in acres).

Farmers are engaged in a number of agricultural activities (i.e. crops, livestock and fishery etc.)

You would feel comfortable having this community host the research team.

You would like to know how to better serve this community.

This community may have CBOs, FBOs or other farming groups.