ABSTRACT

Purpose

The aim of this article is to examine the role of formal and informal leadership for advancing gender equality in forestry education.

Methodology

The article builds on empirical material from focus group interviews and semi-structured interviews with students, teachers and leaders at an agricultural university in Sweden.

Findings

The article finds that leadership for gender equality is not exclusively the role of formal leaders. We show that students and teachers, together with the formal leaders at the university, all expect others to take responsibility while expressing uncertainty about their own opportunities to effect change. Still, teachers appear as a group with great potential to make a difference.

Practical Implications

The article reveals a need for case-based research to clarify issues of gender equality in education and, in particular, how change might happen and who is expected to lead it. We suggest that higher education institutions address this ambiguous division of responsibilities.

Theoretical Implications

The role of formal leadership in gender equality change is continuously stressed in research, policy and practice. We have broadened the definition of leadership in this context beyond formal leadership, and we highlight, for example, teachers and professionals as role models and agents of change.

Originality/Value

The study generates important insights about why gender equality work often fails in higher education, and in particular in the male-dominated forestry sector. It also sheds light on the value of comprehensive case study research.

Introduction

It is often asserted that the success of gender equality work in universities requires active support from the leadership (Blackmore and Sachs Citation2007; De Vries Citation2010; Oligati and Shapiro Citation2002; Bacchi and Everline Citation2010). In this article, we examine the forms this leadership can take and what expectations and ideas underpin this belief.

It has been noted that forestry education at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU), like the entire forestry industry, is permeated by a culture that has elements of discrimination and sexism (Grubbström and Powell Citation2020; Johansson, Johansson, and Andersson Citation2018; Lidestav et al. Citation2011). The need for urgent change was made apparent by Swedish forestry’s own #Me-Too movement #slutavverkat and by an open letter that female students in the forestry program wrote to SLU and the forestry industry in the spring of 2018 (Hallberg Sramek et al. Citation2018). The letter described discrimination and harassment and called for action from SLU and the whole forestry sector. It became clear that despite several years of gender equality initiatives (Andersson and Lidestav Citation2015; Wickman et al. Citation2013), far too little had changed. Demands were made for strong leadership to improve this situation.

Both research and examples of concrete initiatives emphasize the importance of leadership. It is often said that without the commitment of management, nothing will change. Gender equality work involves, from a feminist theoretical perspective, transformative processes where power relations are made visible, challenged and changed if necessary (Meyerson and Kolb Citation2000). A dilemma is that formal leaders are often part of the power structure that needs to change (De Vries Citation2015). Hence, van den Brink and Benschop (Citation2012) believe that it is the hierarchical structures and the inequalities they create that need to change. However, research has also shown how gender equality often, instead of challenging power structures, turn into administrative process of writing strategies and policies (Carbin and Rönnblom Citation2012; Liinason Citation2014) with the result that gender issues fail to be integrated into the work of the organization (Espersson Citation2014; Powell Citation2016). This disconnect means that gender equality work is only to a very limited extent perceived to be part of the core business (Espersson Citation2014; Powell Citation2016).

Criticism has also been directed at how the goal of gender mainstreaming (that gender equality should permeate the entire organization) risks leading to it becoming ‘nobody’s responsibility’ because it is ‘everyone’s responsibility’. Ahmed (Citation2007) argues that it is precisely because the idea of integrating gender equality and diversity perspectives does not have an obvious place in an organization that it needs special focus and specialists who promote the issues. She further believes that when gender equality becomes everyone’s responsibility, it is also assumed that everyone has the knowledge of how best to go about creating equal conditions for all. But, she says, when this knowledge is absent, and it is unclear who is responsible for the integration, then there is a danger that nothing will happen (Ahmed Citation2007). Ahmed also talks about ‘non-performativity’, whereby the management of an organization, by talking publicly about the importance of an issue such as gender equality, can make it appear that there is a commitment to action, whereas, in fact, this public expression serves as a smokescreen to hide an absence of real gender equality work. The image of commitment that is projected becomes an obstacle, rather than an opportunity for change when accounts of discrimination and vulnerability become irrelevant or silenced because the organization gives the impression that nothing like this is going on (Ahmed Citation2006b). Although management’s role in driving change has been emphasized in several studies (Blackmore and Sachs Citation2007; De Vries Citation2010), other studies indicate that an overly one-sided focus on management gives a false picture of the process of change as something that happens from the top-down (Callerstig Citation2014; Ely and Meyerson Citation2000). In this article, we contribute by addressing the complexity of determining responsibility for gender equality change. We do so by showing how students, teachers and the formal leadership view their own and others’ roles and opportunities to create change.

We see leadership as socially constructed, affected by the culture, time and context in which it is conducted. Leadership is thus subject to constant change (Dugan Citation2017). However, even though leadership takes place in the interaction between people, it is also conducted within certain frameworks. One such external framework is the designation of formal leadership positions within the university (Principal, Vice Principal, Deans, Heads of Department and Directors of Studies). There are also other types of leadership that are conducted more informally, such as those held by teachers in relation to the students they teach or by students in student organizations. We emphasize that the boundary between formal and informal leadership can be fluid.

The aim of this article is to examine, through focus groups and interviews, how university management, teachers and students in the forestry program at SLU view the role of formal leadership in leading change towards a more gender-equal education, as well as the ability of informal leaders to affect the process. We ask three questions:

How is the role of leadership in gender equality understood in the organization?

What are the expectations for formal and informal leaders to act as agents of change for gender equality?

How do formal and informal leaders act as agents of change and what factors make it more difficult or easier, for them to take on that role?

We assume that the role of formal management is important, not least in terms of putting gender equality on the agenda and allocating resources to the processes of change, but also by acting as role models. By broadening the understanding of what leadership looks like in forestry education, it also becomes possible to identify the key steps to change. Our study contributes with an in-depth understanding of how leadership for gender equality is understood by people who themselves work or study at the university. This understanding includes both expectations of one’s own role and what is expected of others. In this way, we cast light on the forms that leadership for gender equality can take within the daily life of the organization in higher education.

Theoretical perspectives on gender and leadership

We regard gender and power relations as constantly (re-)created in environments where people meet and interact (West and Zimmerman Citation1987). Gender is constructed socially, historically, as well as culturally. This means that gender is constructed in the way that leadership takes place in everyday organizational practice (Martin and Collinson Citation1999). In this way, organizations can be studied as cultures where gender identities are expressed in discourses, norms, languages, symbols and values, and where power relations are constantly negotiated and can change (Gherardi and Poggio Citation2001). Organizations, such as universities, are contexts in which members are socialized and where their organizational culture is created and recreated, through interaction. Further, the organizational culture studied here is embedded in national and international discourses of gender equality, higher education and forestry. Therefore, the results we present can give us important insights beyond this particular empirical case.

In this study, we see leadership as relational. Thus, leadership is created between people in different contexts where power and trust are constructed in social interactions (Hunt and Dodge Citation2000). Leadership is ‘carried out’ in the course of daily work. This means that it is rooted in historical, social and cultural contexts where there are also perceptions and expectations linked to what leadership means, how it should be practised and who is a leader (Crevani, Lindgren, and Packendorff Citation2010; Yukl Citation2012). Formal leadership implies that the leader has a right to exercise legitimate power over others, by virtue of their position, whereas informal leaders lack this right (Northouse Citation2016; van De Mieroop, Clifton, and Verhelst Citation2020). Non-institutionalized (informal) leadership can be assigned to, for example, teachers on the basis of expert knowledge or something else that causes members of a group to identify that person as an authority (Ensley, Hmieleski, and Pearce Citation2006).

It is important to note that there can be some overlap between formal and informal leadership; formal leaders can also be informal leaders, by virtue of their ability or role in leading others towards change (Dugan Citation2017). We have chosen to call the leadership that teachers exercise informal, even though it can be considered to be in a gray area between formal and informal leadership. The teacher leads a learning process and is an authority in relation to their students. There are also other informal leaders who, due to their informal standing, are normative in different situations and contexts; these can be more senior students or those who are considered ‘right’ in a particular context. In our study, this is exemplified by the female students who wrote the open letter, as well as by the female teachers who supported these students. Other informal leaders who encounter the students during their education are professionals (often in managerial positions) in the forestry sector, who meet students on occasions such as study visits and guest lectures. It is important to point out that one does not necessarily have to self-identify as a leader and role model in order to function as one. Our case study shows the complexity of different formal and informal roles and contributes to leadership theory by investigating the meaning of formal and informal leadership in gender equality change in higher education.

Leadership for gender equality – an overview

Many studies indicate that top management must be committed to driving gender equality initiatives in order for them to have any effect (Blackmore and Sachs Citation2007; Oligati and Shapiro Citation2002). Bacchi and Everline (Citation2010) say, in relation to the possibilities for successful gender mainstreaming, that: ‘Power works through leadership decisions about the relevance of gender to policy’ (Bacchi and Everline Citation2010, 303). Here, power, leadership and decision-making are linked to demonstrate the importance of gender-related issues. If we assume, like West and Zimmerman (Citation1987), that gender is constructed in the course of daily life, then it is also constructed in academic institutions. Hence, the university leaders also become important when they make decisions that affect gender equality and hence ‘create’ gender in the organization. Liff and Cameron (Citation1997) hold that leaders in an organization who act as ‘champions’ for gender equality are central to showing that such equality is prioritized. De Vries (Citation2010) concludes, in her dissertation on gender equality work in the police and academia, that managers and others in senior positions are very important for long-term change to be possible. She argues that grassroots initiatives also depend on support from management, not least financially. Management, from its position of power, can also effectively shut down initiatives. This is something that research on gender equality work at SLU has also shown (Powell Citation2016). People in positions of leadership are often involved in formal decisions where funds are distributed and priorities are set (Mergaert and Lombardo Citation2014), but their role seems to be complex. They can put the issue on the agenda, but their ability to create change is also challenged by themselves and others. Powell (Citation2018) show, for example, how leaders are worried about becoming too associated with gender equality because it is perceived as detrimental to the leadership role.

Furthermore, research has warned that an overly one-sided focus on the role of management creates a false image that change only takes place ‘top-down’. Pascale and Sternin (Citation2005) show how change can occur ‘bottom-up’, and others have highlighted how individuals in an organization (‘tempered radicals’) can create change with small everyday actions (Ely and Meyerson Citation2000). Meyerson and Scully (Citation1995) describe these ‘tempered radicals’ as people who, on the one hand, have their professional standing and position in an organization, but who nevertheless break the norms of the organization: examples could be a woman in a male-dominated organization or a nonwhite person in an organization with almost exclusively white people (Meyerson and Scully Citation1995). While many such people might leave their organizations or adapt to prevailing norms as best they can, others instead choose to try to quietly influence the institutional culture from a position that is sometimes marginalized (Meyerson and Scully Citation1995). They do not necessarily seek radical change but rather ‘small-wins’ (Meyerson Citation2001). These agents for change can have different roles and positions in an organization (Callerstig Citation2014). In this article, we are interested in how people who do not necessarily see themselves as agents of change can be of importance for gender equality work in higher education.

Before presenting our empirical material, we will provide some background information about the forestry context in relation to gender equality.

Inequality and forestry

The forest is traditionally a male-dominated sector, where men have been active and where men have had power (Baublyte et al. Citation2019). This is still the case: 97% of forest companies are owned by men, and 85% of those employed in forest companies are men (SS Citation2016). Even though work in the forest industries today is largely mechanized or office-based, the belief persists that physical strength is required and that the work takes place under harsh conditions (Johansson et al. Citation2017).

The fact that the forest is now also seen as an important part of society’s response to climate change means that new types of competence are needed (for example, in biodiversity and sustainability issues). This has led to hopes that the male dominance of the forest can be broken. Unfortunately, this does not seem to be happening. Instead, research shows that work in the forest remains strongly gender-coded, with women mainly working with the administration, the environment and personnel issues, while men are found in production but also in research (Arora-Jonsson and Ågren Citation2019; Johansson et al. Citation2019). However, Larasatie et al.’s (Citation2019) study of leadership in the North American and Nordic forest industries shows a slow but positive trend where forest companies are increasingly favoring a non-gendered corporate culture.

Since 2017, SLU has had a gender mainstreaming plan, like all other universities and colleges in Sweden (SLU Citation2018). Forestry’s #Me-Too call during 2017–2018, with #slutavverkat and the open letter to SLU and the forest industry, received a lot of attention in the sector and at SLU, which introduced a number of measures in order to show that they took the problem seriously (Högberg et al. Citation2018). Among other things, the university, at the beginning of the semester, introduced theme days for teachers, and discussion sessions with students about discrimination and gender equality. One barrier to change seems to be the culture of silence, in which many feel that it is difficult to act when someone behaves in an unacceptable way (Grubbström and Powell Citation2020). This sheds light on leadership at different levels and on the roles that formal and informal leaders can play in breaking destructive patterns in education.

Methods and empirical material

Our study is based on interviews and focuses groups with university management, teachers and students on the forestry program at SLU during the autumn of 2018 and the spring of 2019.

Interviews and focus groups

We contacted people in different types of management positions and teachers and invited them to be interviewed about their experiences and thoughts on gender equality in forestry education. The managers included individuals from the highest leadership level and from middle management; in most cases, they also had experience as teachers and could therefore provide this perspective too. We selected formal leaders who had been involved in gender equality work and decision-making that had affected gender equality work. Eight of these leaders were from the university and two from forest companies. The leaders from the forest companies had been involved in gender equality work and had a working relationship with the university. We also met four teachers who had experiences from teaching where gender had been discussed. Everyone who was asked to participate in the interview study said yes, except one leader from a forest company who did not reply. The majority of the interviewees were men (one teacher and one in a leadership position were women), which reflects the fact that most people in these positions are men. Some of the interviewees were particularly interested in gender issues, and others had only been involved in gender work because this was one of the areas of responsibility in their position.

It was more challenging to find students to participate in the focus groups. We visited classes, presented the project and asked interested students to contact us. In the beginning, we got mostly women who were interested in gender issues. Through the student union and with the help of teachers, we were able to recruit male students and students that were not especially interested in gender issues to participate. In this way, we obtained different perspectives from students who had experienced, observed or only heard of discrimination towards women. In the focus groups, we introduced questions to stimulate discussion about: how a forestry student should be and behave; relations between women and men on the course; reactions to #slutavverkat and the open letter; explanations for why discrimination and sexual harassment continue; and how gender equality in the program could be increased. Two of the focus groups consisted of women only, one of both women and men, and one of men only. A total of 14 students participated in the focus groups: seven women and seven men. We also conducted three individual interviews with female students who could not participate in the focus groups or preferred an individual interview. gives an overview of the empirical material and the terms we use when we present the material.

Table 1. Empirical material.

Interviews and focus groups lasted about 1–2 h. We are aware of the reticence from participants towards expressing criticism and questioning gender equality; this is often reflected in our material through participants describing the behavior of others rather than of themselves. Our experience from recruiting students to the study showed us that a range of strategies were needed to contact participants and find students with different perspectives and interests in gender issues.

Ethical issues

Issues related to gender equality, especially concerning discrimination and sexual harassment, are sensitive. We have therefore anonymized all quotes and, with regard to the groups of teachers and people in management positions, we have chosen not to identify the sex of individuals, given that there are so few women in the organization.

Participating in this type of study tends to highlight problems within the organization. Revealing and discussing these problems openly risks throwing a negative light on the education program through, for example, being highlighted in the press and social media as an example of a problematic environment. When this happens, the ‘it happens there but it could never happen here’ effect often sets in. This means that it is possible, by pointing out that inequality exists elsewhere, to convince oneself that it does not exist in one’s own organization (cf. Johansson Citation2020). It is therefore important to emphasize two things that motivate this type of study. Firstly, the value of openly discussing the causes of the problems that exist in one’s own organization in a case study. This, in turn, provides an understanding of the complexity and difficulties of changing culture, but can in the long run, help speed up the process towards a more gender-equal education. Secondly, the general value of using this type of case study to provide tools for other organizations to recognize their own specific internal challenges.

Analysis

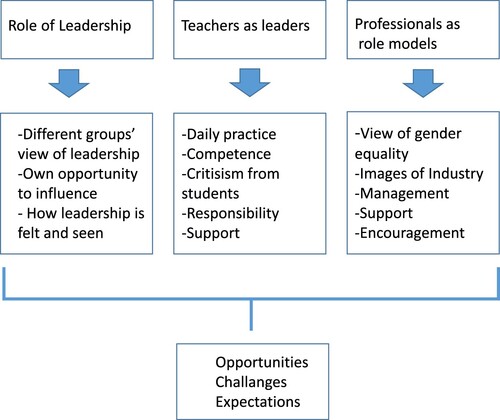

Our analysis was performed in three stages. The first stage was carried out immediately after the focus groups and interviews, when we summarized our impressions. After verbatim transcription of the recordings from the focus groups and interviews, the second stage was a content analysis, involving coding the text to identify the main themes. These were: ideas about the role of leadership; the importance of teachers as leaders; and the importance of professionals as role models. In the third stage of in-depth analysis, each main theme was divided into sub-themes ().

Ideas about the role of leadership could be sub-divided as different groups’ views about leadership; their own opportunities to influence; and how leadership is felt and made visible. The importance of teachers as leaders included the sub-themes: daily practice; competence; criticism from students; teachers’ responsibilities; and the role of teachers as support for students. In the importance of professionals as role models, sub-themes identified what these role models could communicate: views on gender equality; images of the industry; management; support and encouragement. The overarching sub-themes could be described as analysing opportunities, challenges and expectations associated with leadership and, more specifically, the role of teachers and professionals. Our theoretical understanding of leadership as relational, that is, constructed in social interactions and rooted in historical, social and cultural contexts, was an important assumption when we performed this analysis, guiding our examination of important relations and the specific context in which the culture has evolved.

Results

Understanding gender equality and leadership in the organization

If the top management does not do so, then no one else in the organization will prioritize the issue. (ILE)

A clear picture emerges from our interviews and focus groups that students and teachers, as well as formal leaders, are dependent on others for progress with gender equality work. This leads to a form of circular reasoning. The higher levels of management feel that it is difficult for them to influence everyday working practices and that they should not control individual institutions in detail. Leaders at the intermediate level, in turn, believe that without a clear signal from the top management that this is a priority, it is difficult to get a hearing for the issues among their employees. Teachers, for their part, find their role difficult. They believe that they lack the knowledge to teach about and address discrimination in teaching and in relation to students. The students, meanwhile, demand reaction and action both from senior management and from their teachers. Although the formal responsibility can be traced organizationally, no real clarity is experienced. This is expressed when an intermediate leader says:

And then there is probably also an ambiguity, who is really responsible when you see things? What is the faculty’s responsibility, what is your responsibility as a teacher, what are you expected to do if you discover something? Because these are difficult things to deal with if you see that something is not working. (ILE)

The students say that they are not aware of the management’s position on gender equality and that they do not know what the management really thinks. The only exception is a woman who is responsible for gender equality issues within the organization (FG3MW, IS, FG4M). Ahmed (Citation2006a) believes that a concept (in this case, gender equality) is associated with certain bodies/people. This association is also clear in our study and, as Jordansson and Peterson (Citation2019) have shown, gender equality still often seems to be regarded as an issue for women, driven by women. This, in turn, risks leading to gender equality issues not involving all managers in a way that is visible to students.

The question of responsibility and where management should and can go in and take control is complex, not least because managers themselves do not always perceive themselves as the right people to pursue the issues, despite a formal mandate. In some cases, they feel that top-down signals and strategies for gender equality do not necessarily lead to change. One manager puts it this way:

The work is institutionalized, but the problem is not only that, it is quite clear that management has a great responsibility, but it is important to mobilize the employees and that is where it usually falls down. (ILE)

This interviewee emphasizes that the management can only do part of the work with gender equality, and that it is in the daily activities at the university that change can really take place, but where it, in fact, fails to happen. Jordansson and Peterson (Citation2019) believe that the slow progress towards gender equality is due to the fact that it challenges the daily routine of work, its positions and its power relations. Next, we will analyse the expectations of teachers and the opportunities and challenges that they themselves experience in the daily practice of gender equality work.

Teachers as agents of change

Despite the fact that Swedish colleges and universities have worked with gender equality for many years, it is often regarded as a separate issue from their regular work (Powell Citation2016). The relationship between what is considered to be ‘the important and proper’ work, and gender equality is expressed by a teacher as follows:

This is an issue that you have to say is important, that you are going to work with this. But when you begin thinking about how the programmes should look, who should decide and what should be included in the course and who should be there as a teacher and all that. Then all of a sudden you fall back to the old norms, the old way of thinking that you have. (IT)

This quote illustrates that there is a difference between saying that gender equality is important and the more challenging application of these thoughts in practice. Gender equality work tends to be reduced to individual lectures or seminars, and students feel that their teaching has contained little about gender equality (FGWM, FGM, FGW1 & FGW2) and describe initiatives to promote gender equality as a one-off, short-term actions (FGM).

In relation to teaching and teachers’ participation in gender equality work, concerns are also raised about who has sufficient competence to teach and to lead discussions about gender equality issues. Our study reveals that a common solution is to use external expertise. This can send signals that further strengthen the idea that gender equality work is not part of the regular activities and thus falls outside the teacher’s responsibility. The teachers are given mixed messages – that they are responsible for dealing with the issue, but at the same time that they lack the competence to do so.

The teachers say that they receive two types of criticism from students when it comes to gender equality in teaching: on the one hand, criticism about the teachers’ own action or lack of action in concrete situations; and on the other hand, criticism if they raised gender equality as a subject within education. As an example of the first type of criticism, both students and teachers describe situations when people ‘joked’ in a way that was perceived as offensive by students. Students have then criticized teachers for not drawing attention to or reacting to the inappropriateness of this. The second criticism is that some students believe that gender equality is not a subject that belongs in forestry education at all. One of the teachers says:

But people claim that it is irrelevant, that I should be talking about … forest management, not about gender-related issues. (IT)

From some students, there has thus been resistance to discussing gender equality within the framework of forestry. The teacher interviews reveal that critical viewpoints have also emerged in evaluations, where students have expressed the opinion that gender equality does not belong in the course.

The focus groups have talked about the difficulty of starting discussions about gender equality, even on those occasions that have been set aside for just this. Students describe discussions that faltered and fell silent. Those who were interested in the issues have felt silenced by students who, for example, expressed in advance the opinion that gender equality is nonsense and that the occasion would be just a show for political correctness (FGW1 & FGW2).

Some teachers only contribute a short segment to a course, where they focus on their special area of expertise. In this way, gender equality as a theme is disconnected from subject teaching and ambiguity regarding leadership and responsibility issues becomes apparent. When a teacher does not meet the students very often, it is difficult for them to create relationships and get to know the students. This, in turn, can lead to it being more difficult for teachers to see problems in the student group, and any issues that are discovered can be considered someone else’s responsibility to sort out (ILE). However, the role of the teacher has been clarified as a result of #slutavverkat and the open letter. A teacher talks about his feelings after the arrival of the open letter:

So that I felt, I was like a little retroactively disappointed in myself that I had not been able to achieve such confidence. That I could have heard and sort of helped and resolved those situations that have been … until #slutavverkat I thought, come on, they are grown-ups after all. I try to monitor, manage my subject as well and do my job as a teacher. And what they do at their parties and stuff, it's actually not my responsibility to get involved. And then after the event it has felt that it is actually about the study environment and my ability to do my job, when it has that degree of impact on the work environment for the students. So that, in retrospect, I have understood that I need to … get more involved in order to be able to do my job as a teacher … .To build some kind of foundation so that we, as teachers, can actually be a channel for curbing bad behaviour. (IT)

This teacher’s account highlights the potential of the teacher as a leader: that an increased engagement can affect students’ study environment and promote gender equality.

Role models

Both female and male students believe that working men and women in the forestry sector are important both for support and as role models. The male students say that they need help to start a debate about gender equality and their own behavior:

… I guess you must have some who go into the breach and start to lift the debate more and help us get started with it because we will not magically change ourselves unfortunately (FGM).

During their course, the students encounter professionals working in the forestry sector as lecturers, during field visits and at dinners (attended by invited forestry professionals). It emerges from our focus groups and interviews that these meetings are an important part of the students’ education because they gain insight into the opportunities that exist for them after graduation and make valuable contacts in the industry. The contact with professionals also gives students insight into the industry from a gender equality perspective. The students feel that an employer has an opportunity to show that those who are to be employed in the company are expected to behave in a nonsexist way and that this message becomes very powerful when it comes from a large company where many of the students may seek work (FGM, FGWM).

However, the images of companies’ gender equality work given in focus groups and interviews are mixed. On the one hand, the students have met representatives of companies where gender equality issues have emerged as very important. On the other hand, the students describe meeting men in leading positions in the forestry industry who have spoken negatively about women and, for example, used sexist jokes at dinners. Events like these created great concern about what type of managers the students would meet in the future and to what extent they would have this same outdated view of women. These encounters also had the effect of deterring students from applying to the companies represented by these individuals (IS, FGW 1 & FGW2).

As the forest sector is male-dominated, female teachers and working women have a special position as role models. In line with research on how gender is constructed in organizations (West and Zimmerman Citation1987), we also see how ideas about women and men, and who can be a role model for the students, are created in the organization, for example, in different teaching elements.

Women as leaders and teachers in forestry

The students emphasize the importance of having female teachers, of meeting women who already work in the forest industry, and of lecturers using examples of both men and women in their teaching. If a teacher refers to the person working in the forest as a man, female students can feel excluded. One of the female students puts it this way: ‘Then you feel like someone who has been invited to watch, or that you are actually there as a spectator’. It is about being seen and feeling part of the forest industry.

Our material contains descriptions of women as role models and support, but also reports what the students perceive to be a fear among some senior women in the industry of being associated with gender equality issues. In connection with #slutavverkat, some female teachers and female leaders in forest companies played a very important role for the group of students who later wrote the open letter. These women arranged opportunities for the students to meet, but they also contributed with their experiences and encouraged the students to dare to publish the letter.

The importance of women in leadership positions supporting and encouraging other women is something that the students highlight in one of the focus groups:

Student 2: Sometimes you can feel like this that you may be able to find support from a professional woman as well. But I think it feels really scary to try to talk to someone who has been there for ages about this because it feels like they’ll just, like, say the same thing as a man would say maybe, or maybe be even harder.

Student 3: It's very likely, like, it’s tough here, you need to have skin on your nose … they have had to fight and now goddammit it’s your turn (laughs).

Student 2: Yes, exactly, yes, a bit like that. It would have been good to hear as well as from older women, who after all have been in the industry for a long time. That this is how I have handled this and there are a lot of things that I might have done differently but, yes but kind of just someone who says something, because during the whole #slutavverkat there’s like not a single female forestry official who has said anything … any of those big names. None of them have said anything about the culture in the forest industry.

Interviewer: Why do you think that is so?

Student 3: There may be some kind of fear of …

Student 1: Not to discourage us, or I don’t know.

Student 3: not to be destabilized … that they are so afraid of their position or kind of respect that they do not dare, so they have far too many men's eyes on them, I would say. That they dare not stand out because it costs so much in such a position. (FGW1)

This discussion shows that the female students would have liked influential women in the forest industry to relate their own experiences. In interviews and focus groups, students describe some women in the forest industry as harder than men. This is explained in our study by the fact that it has been important for many women to fit in and that the women, therefore, did not want to feel that there are different conditions for men and women in the industry. Some have described that some women they met were more devoted to traditions and norms than their male student colleagues (ILE, IT, IT). In addition, it seems to be more difficult for women who want to make a career to also be associated with gender equality work (ILE). This can, in part, be explained by the fact that it can create conflicts or is considered to be something that does not belong in the core business and is not prioritized (Espersson Citation2014). There is a risk that the silence that the students experience from the female leaders conveys the message that if you are to achieve a prominent position in this industry, you must be quiet and adapt. What is clear in interviews with students is that in cases where women in senior management positions in the forest industry have expressed support for gender equality work and themselves have been open with their own experiences of a negative male culture, this has been important for students (FG2W). The working women have thus become important role models.

Concluding discussion

In this article, we have focused on how university management, teachers and students in the forestry program at SLU view the role of formal and informal leadership in creating a more gender-equal education. We have studied the ideas that exist about the role of leadership in gender equality, how teachers can act as agents of change, and how students view the professional leaders they meet during their education and their role in fostering a gender-equal forestry sector.

The study contributes, with its detailed empirical case study, to a discussion about gender inequality in forestry education in Sweden and beyond. Even if our study is conducted at one particular university in Sweden, we see the organizational cultures developing here as embedded in larger national and international discourses on gender equality in higher education institutions. In this study, we have scrutinized the taken for the granted idea that formal leadership is central for any gender equality change (Blackmore and Sachs Citation2007; De Vries Citation2010; Oligati and Shapiro Citation2002; Bacchi and Everline Citation2010) by broadening the meaning of leadership in this context beyond the formal. By identifying different ways in which leadership is taking place, by different actors, we have highlighted central mechanisms in the everyday practice of higher education and teaching that affect the opportunities for realizing gender equality.

In agreement with studies by Ahmed (Citation2006a) and Bacchi and Everline (Citation2010), we see how the issue of responsibility ‘slides around’ in the organization. It is, therefore, important that universities work with clear directives on the division of responsibilities for gender equality in forestry education.

Furthermore, this study contributes to an increased understanding of the nature of leadership. We see that formal leaders, teachers, and students are not clear about who should actually lead and carry out the practical and daily work for gender equality and how it should be done, despite the fact that strategies and policies exist. Students want formal leaders to be vociferous about and address the problems of inequality and thus show a clear stance on the issue. Formal leaders at the university believe that gender equality is important, but at the same time, express an unwillingness to get involved in the organization too much and state that they want to avoid directing the work from above. We also see a concern among formal leaders about becoming too associated with gender issues (Powell Citation. 2018).

In our analysis, the teachers appear to be central to the process of change in forestry education, as they are often immersed in the activities of the organization and meet the students. But their role, which is in the gray zone between formal and informal leadership, is not simple. While some students demand more focus on gender equality, others believe that it is just politically correct to talk that does not belong in their education. We see how a lack of knowledge (experienced or real) about how to talk about gender equality creates insecurity among teachers that can lead to them avoiding raising the issue with their students. This is at the same time as students are looking for encouragement and support from their teachers. Teachers are given conflicting signals regarding their opportunities to talk about and carry out active gender equality work. On the one hand, they are asked to dare to discuss gender equality with the students and to act and react when something happens. Both teachers and students we interviewed believe that teachers have great opportunities to influence the study environment by drawing attention to discrimination and inequalities among students. On the other hand, SLU frequently brings in external experts when gender equality is on the agenda, which can be seen as a way of disconnecting gender equality from other parts of education (cf. Espersson Citation2014). This sends a signal that working towards gender equality is not part of the teachers’ remit. It is clear that teachers need support to feel more confident about raising gender issues within education.

At the same time, we see examples of what Meyerson and Scully’s (Citation1995) call ‘tempered radicals’ in our study, and how these individuals have contributed to important gender equality work. One instance of this is the teachers and formal leaders who encouraged the authors of the open letter to have the confidence to publish it.

The students in our study highlight the formal leaders, teachers and representatives of the forest industry as important role models. Female students identify successful women in the forest sector as especially important in an environment that has been described as discriminatory and difficult for female students. They believe that the negative masculine culture that exists in forestry education and in the sector benefits the men who meet the norm, but that many (both women and men) feel that they do not fit in, and thus there is a need for a wider range of role models for the students (Grubbström and Powell Citation2020). If we understand organizations as cultures (Gherardi and Poggio Citation2001; Gherardi Citation1995), where gender is created through norms, daily practices, discourses and languages, then individuals’ actions (or lack of actions as Ahmed (Citation2006a) shows) play an important part in determining what change is possible. We see in our study how these individuals can proactively act for gender equality and thus demonstrate the importance of change.

Our study also shows how professionals, as informal leaders who, in various ways, participate in the education, are important for the culture that develops and thus also have the opportunity to be agents of change in daily practice. As role models, formal as well as informal leaders such as teachers, professionals and students in leading positions play a vital role in changing gendered cultures. Therefore, we see it as essential that higher education institutions enable discussions that develop awareness about what leadership means in a particular context and about the responsibility that leadership brings. Our results suggest that this is of particular importance in education programs with close collaboration with industry and professionals.

In conclusion, we have shown how students and teachers, together with the formal leaders at the university, all expect others to take responsibility while many express uncertainties about their own opportunities to influence and change. However, teachers appear as a group with great potential to make a difference. Their role as leaders in the classroom and as role models for the students means that they have the opportunity to act, to take the gender equality work from thoughts and written words to the practical daily reality of teaching. This does not mean that the main responsibility for gender equality work in education should lie with the teachers. Formal leaders must continue to speak out about gender issues, and they must fund and support their staff. They must also dare to continue being, or become, role models and dare to be associated with the issues.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Skogssällskapet for their generous support for this research as a part of the research project: To stop counting bodies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Stina Powell

Stina Powell, Ph.D., is a researcher in Gender Studies and Environmental Communication with a particular focus on sustainability from a feminist perspective. She teaches at the Master of Environmental Communication and is acting Head of Division.

Ann Grubbström

Ann Grubbström, Ph.D. Associate Professor, Department of Urban and Rural Development, Unit of Environmental Communication, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden. Ann Grubbström’s research focuses on gender and forestry as well as generational issues with regards to farming and in rural areas in Sweden and Estonia. Ann is responsible for the Supervision courses at SLU, and she also teaches Environmental Communication at SLU.

References

- SLU Gender integration plan 2018. 2017–2019 ua: 2017.1.1.1-1795.

- Ahmed, Sara. 2006a. “Doing Diversity Work in Higher Education in Australia.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 38 (6): 745–768.

- Ahmed, Sara. 2006b. “The Nonperformativity of Antiracism.” Meridians 7 (1): 104–126. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40338719.

- Ahmed, Sara. 2007. “The Language of Diversity.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 30 (2): 235–256.

- Andersson, Elias, and Gun Lidestav. 2015. Gender Equality as a Joint Forestry Sector Strategy. Dept of Forest Resource Management SLU. Report: 4442015.

- Arora-Jonsson, Seema, and Mia Ågren. 2019. “Bringing Diversity to Nature: Politicizing Gender, Race and Class in Environmental Organizations?” Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 2 (4): 874–898.

- Bacchi, Carol, and Joan Everline. 2010. Mainstreaming Politics: Gendering Practices and Feminist Theory. Adelaide: University of Adelaide Press. http://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/33166

- Baublyte, Gintare, Jaana Korhonen, Dalia D’Amato, and Toppinen Anne. 2019. “‘Being one of the Boys’: Perspectives from Female Forest Industry Leaders on Gender Diversity and the Future of Nordic Forest-Based Bioeconomy.” Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research 34 (6): 521–528.

- Blackmore, Jill, and Judyth Sachs. 2007. Performing and Reforming Leaders. New York, NY: SUNY.

- Callerstig, Ann-Charlott. 2014. Making Equality Work: Ambiguities, Conflicts and Change Agents in the Implementation of Equality Policies in Public Sector Organisations. Tema Genus. Linköpings universitet. Linköping: LiU Electronic Press.

- Carbin, Maria, and Malin Rönnblom. 2012. “Jämställdhet i akademin- en avpolitiserad politik?” TGV (1–2): 75–94.

- Crevani, Lucia, Monica Lindgren, and Johann Packendorff. 2010. “Leadership, not Leaders: On the Study of Leadership as Practices and Interactions.” Scandinavian Journal of Management 26 (1): 77–86.

- De Vries, Jennifer. 2010. “A Realistic Agenda? Women Only Programs as Strategic Interventions for Building Gender Equitable Workplaces.” PhD thesis, UWA.

- De Vries, Jennifer. 2015. “Champions of Gender Equality: Female and Male Executives as Leaders of Gender Change.” Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal 34 (1): 21–36.

- Dugan, John. 2017. Leadership Theory: Cultivating Critical Perspectives. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

- Ely, Robyn, and Debra Meyerson. 2000. “Advancing Gender Equity in Organizations: The Challenge and Importance of Maintaining a Gender Narrative.” Organization 7 (4): 589–608.

- Ensley, Michael D., Hmieleski Keith M., and Pearce Craig L. 2006. “The Importance of Vertical and Shared Leadership Within New Venture Top Management Teams: Implications for the Performance of Startups.” Management Department Faculty Publications 71.

- Espersson, Malin. 2014. “Isärkoppling som strategi. Om spänningen mellan meritokrati och likabehandlingsarbete på ett svenskt lärosäte.” In Att bryta innanförskapet, edited by E. Sandell, 122–143. Lund: Makadam.

- Gherardi, Silvia. 1995. Gender, Symbolism and Organizational Cultures. New York, NY: Sage.

- Gherardi, Silvia, and Barbara Poggio. 2001. “Creating and Recreating Gender Order in Organizations.” Journal of World Business 36 (3): 245–259.

- Grubbström, A., and Stina Powell. 2020. Persistent norms and the #metoo effect in Swedish forestry education. Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research 35(5–6): 308–318.

- Hallberg Sramek, Isabella Lina, Arnesson Ceder, Johanna Hägglund, Felicia Lidman, and Jenny . 2018. “Från hashtag till handling.” Öppet brev till SLU och skogsnäringen. https://www.skogen.se/nyheter/oppet-brev-fran-hashtag-till-handling 2018-03-21

- Högberg, Peter, Karin Holmgren, Göran Ståhl, Anders Alanärä, and Ann Dolling. 2018. “Vi måste höja ambitionerna.” SLUs svar på det öppna brevet, 2018-04-03.

- Hunt, James, and George Dodge. 2000. “Leadership Déjà vu all Over Again.” The Leadership Quarterly 11 (4): 435–458.

- Johansson, Maria. 2020. “Business as Usual? Doing Gender Equality in Swedish Forestry Work Organisations.” PhD thesis, Luleå University of Technology.

- Johansson, Kristina, Elias Andersson, Maria Johansson, and Gun Lidestav. 2019. “The Discursive Resistance of Men to Gender-equality Interventions: Negotiating “Unjustness” and “Unnecessity” in Swedish Forestry.” Men and Masculinities 22 (2): 177–196.

- Johansson, Maria, Kristina Johansson, and Elias Andersson. 2018. “#MeToo in the Swedish Forest Sector: Testimonies from Harassed Women on Sexualised Forms of Male Control.” Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research 33 (5): 419–425.

- Johansson, Kristina, and Gun Lidestav. 2017. “The discursive resistance of men to gender equality interventions. Negotiating ”unjustness” and ”unnecessity” in Swedish forestry.” Men Masc 22 (2): 177–196.

- Jordansson, Birgitta, and Helen Peterson. 2019. “Jämställdhetsintegrering vid Svenska Universitet och Högskolor. Det Politiska Uppdraget återspeglat i Lärosätenas Planer.” Kvinder Køn & Forskning 28 (1-2): 58–70.

- Larasatie, Pipiet, Gintare Baublyte, Kendall Conroy, Eric Hansen, and Anne Toppinen. 2019. “‘From Nude Calendars to Tractor Calendars’: the Perspectives of Female Executives on Gender Aspects in the North American and Nordic Forest Industries.” Canadian Journal of Forest Research 49 (8): 915–924.

- Lidestav, Gun, Elias Andersson, Solveig Berg Lejon, and Kristina Johansson. 2011. “Jämställt arbetsliv i skogssektorn.” SLU, rapport 345.

- Liff, Sonia, and Ivy Cameron. 1997. “Changing Equality Cultures to Move Beyond ‘Women’s Problems’.” Gender, Work and Organization 4 (1): 35–46.

- Liinason, Mia. 2014. “Maktens skiftningar.” En utforskning av ojämlikhetsregimer i akademin. TGV 35 (1): 75–97.

- Martin, Patricia Yancey, and David Collinson. 1999. “Gender and Sexuality in Organizations.” In Revisioning Gender, edited by M. M. Ferree, J. Lorber, and B. Hess, 285–310. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Mergaert, Lut, and Emanuela Lombardo. 2014. “Resistance to Implementing Gender Mainstreaming in EU Research Policy.” In ‘The Persistent Invisibility Of Gender In EU Policy’ European Integration online Papers (EIoP), Special issue 1, edited by Weiner, Elaine and Heather MacRae, Vol. 18, 1–21, http://eiop.or.at/eiop/texte/2014-005a.htm

- Meyerson, Debra. 2001. Tempered Radicals: How People Use Difference to Inspire Change at Work. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Meyerson, Debra E., and Deborah M. Kolb. 2000. “Moving out of the `Armchair’: Developing a Framework to Bridge the Gap Between Feminist Theory and Practice.” Organization 7 (4): 553–571.

- Meyerson, Debra E., and Maureen A. Scully. 1995. “Crossroads Tempered Radicalism and the Politics of Ambivalence and Change.” Organization Science 6 (5): 585–600. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2634965

- Northouse, Peter. 2016. Leadership: Theory and Practice. Los Angles, CA: SAGE.

- Oligati, Etta, and Gillian Shapiro. 2002. “Promoting Gender Equality in the Workplace.” Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions.

- Pascale, Richard Tanner, and Jerry Sternin. 2005. “Your Company’s Secret Change Agents.” Harvard Business Review 83 (5): 72–81.

- Powell, S. 2016.Gender equality and meritocracy. Contradictory discourses in the academy. Diss. Uppsala: SLU.

- Powell, Stina., Ah-King Malin, and Hussénius Anita. 2018. “Are we to become a gender university?” Facets of resistance to a gender equality project. Gender, Work & Organization 25(2): 127–143.

- SS (Statistics Sweden, SCB) Statistics over professions and employment. 2016.

- van De Mieroop, Dorien, Jonathan Clifton, and Avril Verhelst. 2020. “Investigating the Interplay Between Formal and Informal Leaders in a Shared Leadership Configuration: A Multimodal Conversation Analytical Study.” Human Relations 73 (4): 490–515.

- van den Brink, Marieke, and Yvonne Benschop. 2012. “Slaying the Seven-headed Dragon: The Quest for Gender Change in Academia.” Gender, Work & Organization 19: 71–92.

- West, Candace, and Don H. Zimmerman. 1987. “Doing Gender.” Gender and Society 1 (2): 125–151. https://www.jstor.org/stable/189945

- Wickman, Kim, Ann Dolling, Gun Lidestav, and Jonas Rönnberg. 2013. “Genusintegrering och jämställdhetsarbete vid fakulteten för skogsvetenskap SLU.” Rapport 21.

- Yukl, Gary. 2012. Ledarskap i organisationer. Harlow: Prentice Hall.