ABSTRACT

Purpose

To explore young peoples’ motivation for engaging in agricultural education. Autonomous and controlled forms of extrinsic and intrinsic regulation are discussed regarding young peoples’ decision to pursue an agricultural education.

Design/methodology/approach

A qualitative research approach was applied comprising of purposive and snowball sampling for 28 face-to-face, in-depth, semi-structured interviews.

Findings

An understanding of the motivational regulations which mobilise young people to engage in agricultural education is provided. This paper sheds light on the psychological processes energising individuals to engage with agricultural education.

Practical implications

The research highlights the importance of understanding motivation for engaging in agricultural education, and subsequent impacts on education programmes and educators.

Theoretical implications

This paper contributes to pragmatic insights which demonstrate the importance of understanding young peoples’ motivation for engaging in agricultural education. The paper builds on previous studies by using S.D.T. as a framework for understanding motivational processes within agricultural education.

Originality/value

This paper supports an understanding of the motivational regulations which mobilise young people to engage with agricultural education.

Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to explore young peoples’ motivation for engaging in agricultural education. The findings presented discuss how autonomous and controlled forms of extrinsic and intrinsic regulation motivate young people to embark on an agricultural education journey. Zagata and Sutherland (Citation2015) call for a more nuanced understanding of young people in agriculture, surpassing the basic facts, and delving deeper into understanding the dynamics of young peoples’ needs within the sector. Accordingly, this paper adds to this body of work by providing a greater understanding of young peoples’ motivation for engaging in agricultural education, and allows for a discussion of the implications for agricultural education policies and classroom strategies.

Agricultural education is the teaching of agriculture, natural resources, and land management to prepare students for the agri-food industry (NAAE Citation2021). Given the sector specific nature of agricultural education, various stakeholders engage both directly and indirectly with the teaching and learning process. These stakeholders include farm families, local communities, government, policy makers, industry experts, and researchers. Internationally, young farmers represent a highly skilled labour force in terms of technical expertise and farm productivity (Cush and Macken-Walsh Citation2016), having the potential to impact positively on the local economy (Zagata and Sutherland Citation2015), environment (Vanslembrouck, Van Huylenbroeck, and Verbeke Citation2002), and social disposition of rural communities (Wynne-Jones Citation2017). Young farmer studies provide evidence of increased levels of productivity, profitability, and investment (Cush and Macken-Walsh Citation2016; Hamilton, Bosworth, and Ruto Citation2015), signifying the value of an agricultural education, particularly within the context of sustainable, global food production which gives consideration to climate change mitigation and the environmental impact of agricultural practices. The European Union recognises the importance of young farmers to the future of farming and acknowledges the importance of generation renewal to the longer-term survival of the sector (Brennan et al. Citation2016; Hamilton, Bosworth, and Ruto Citation2015). The number of young farmers across many developed countries, including Europe and the United States, over the last decade has declined due to social, economic and technological changes (Duesberg, Bogue, and Renwick Citation2017; Leonard et al. Citation2017; May et al. Citation2019). In Europe, young farmers represent only 11% of the total farming population (Eurostat Citation2021) with almost one-in-four farms managed by a farmer greater than 55 years of age and over one-third of farm holders over 65 years of age (Eurostat Citation2021). Consequently, political measures were introduced at the European level to encourage young farmer participation and to support the establishment of new farms (European Commission Citation2013; Zagata and Sutherland Citation2015). Such policy instrumentation resulted in a considerable increase in numbers enrolling on agricultural education programmes in Ireland as young people embarked on a journey towards young trained farmer statusFootnote1 (McKillop, Heanue, and Kinsella Citation2018; Teagasc Citation2021). Prior to 2014, annual enrolments on agricultural V.E.T. (Vocational Education and Training) programmes was around 400–500 students, with a dramatic increase from 2014 onwards, numbers remain in the region of 1500–1600 students today (Teagasc Citation2021).

Within the agricultural context, understanding the motivation of young people engaging with agricultural education is imperative, in an era where the farming population is aging and global demands regarding sustainable food production are increasing. Motivational regulation for engagement in agricultural education is important in terms of the teaching and learning nexus with regard to learner engagement, promotion of sustainable practice, and the ability to change mindset and broaden horizons. Consequently, this paper investigates young peoples’ motivation for engaging in agricultural education. The overarching research question is: what motivates young people to engage in agricultural education? The answer to this question sits within the complex nature of human motivation and behaviour.

Theoretical framework

Motivation is a dynamic, internal process guiding the achievement of a result, goal, or action (Gibson Citation2018) generally defined as the energy, direction, and persistence of behaviour (Howard et al. Citation2016; Pinder Citation1998). Although many theories have been applied to student motivation (e.g. Occupational Choice Theory (Beecher et al. Citation2019); Expectancy Value Theory (Ball et al. Citation2016); Theory of Planned Behaviour (Zhou, Chan, and Teo Citation2016); Social Cognitive Theory (Ruzek and Schenke Citation2019), this study employed Self-Determination Theory (S.D.T.) as it has been used as a framework for understanding motivational processes within education, more specifically with regard to specific subject(s) choice (Inegbedion and Islam Citation2020; Guay Citation2022). S.D.T. is a well-established motivation theory, however, it has only recently been applied to the subject area of agriculture (see, for example, Charatsari, Lioutas, and Koutsouris (Citation2017) and Inegbedion and Islam (Citation2020)).

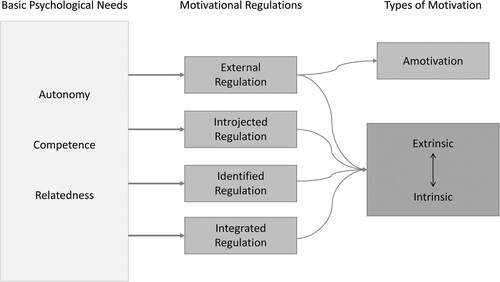

S.D.T. differentiates between autonomous and controlled forms of human motivation (Deci and Ryan Citation2012). S.D.T. suggests humans have three basic psychological needs (B.P.N.), namely autonomy (individual’s need to behave based on choice), competence (ability to maintain and enhance skills to be effective and increase capability), and relatedness (need for social connections with society/others and acceptance by others), which are considered essential for human functioning (Ryan and Deci Citation2017). However, Ryan and Niemiec (Citation2009) highlight some of the challenges associated with S.D.T., particularly given its foundations in quantitative methods, being ‘ … unabashedly a strong empirically based theory’ (p264). This paper applies a theoretical and analytical framework derived from S.D.T. which addresses the criticisms of the theory by applying a qualitative approach (Hancox et al. Citation2018; Kinnafick, Thøgersen-Ntoumani, and Duda Citation2014; White et al. Citation2020; Wood Citation2019) in exploring young peoples’ motivation for engaging in agricultural education. Thus, the theory provides a framework within which young peoples’ motivation for engaging in agricultural education can be understood. Accordingly, the paper focuses on young peoples’ motivational regulations for engaging with agricultural education. Autonomous forms of motivation encompass intrinsic and some extrinsic motivation which are self-determined, compared to controlled forms of motivation which are mainly extrinsic in nature. Intrinsically motivated individuals experience greater interest, enthusiasm, and self-confidence leading to greater performance, persistence, and creativity (Deci and Ryan Citation1991), in addition to an increased feeling of vitality (Nix et al. Citation1999), and improved self-esteem (Deci and Ryan Citation1991). On the contrary, amotivation, refers to a disinterest or lack of desire to engage in an activity, often resulting in individuals experiencing a feeling of detachment from activities, lacking control over a situation, resulting in reduced investment of time and energy towards activities/goals (Howard et al. Citation2016). Subsequently, the analytical framework for this paper is derived from S.D.T. as illustrated in .

Extrinsically motivated behaviours may not be sustainable in the long term as the effects of external interventions generally subside (Deci and Moller Citation2005). However, Herzfeld and Jongeneel (Citation2012) argue the introduction of extrinsic forms of motivation can undermine an individual’s intrinsic motivation to participate, often resulting in individual disinterest or stagnation due to a controlling system where rewards are dependent on behaviours an individual may not truly believe in and individual capacities to learn, adapt, and change are constrained (Deci and Moller Citation2005; Payne, Nicholas-Davies, and Home Citation2019).

The motivational regulations (illustrated in ) encompass introjection: a form of controlled intrinsic motivation; and identified regulation: a form of autonomous intrinsic motivation. Introjection denotes an individual’s desire for self-approval to avoid shame/guilt (Deci et al. Citation1994). Within the agricultural context, intergenerational transfer and patrilineal succession represent introjection in many instances (Cassidy Citation2019; Grubbström, Stenbacka, and Joosse Citation2014) and are captured within this paper. Identified regulation signifies autonomous behaviour where an individual recognises and appreciates the value and importance of an activity/behaviour. For example, recognising the value of agricultural education may encourage individuals to engage for reasons personally important to themselves which may help fulfil their B.P.N. Finally, integrated regulation represents the decision to engage with an activity, thus this type of motivation is exclusively internal and highly autonomous by nature (Deci and Ryan Citation2012).

The rationale for the establishment and promotion of agricultural colleges was the potential for the advancement in technical knowledge, decision-making abilities, and problem-solving skills among the farming population (Feder, Murgai, and Quizon Citation2004; Ortiz et al. Citation2004; Tomlinson and Rhiney Citation2018). Charatsari, Lioutas, and Koutsouris (Citation2017) concluded that autonomous motivation (i.e. identified and integrated) was associated with farmer participation in competence development projects. However, little consideration has been given to a young person’s motivation to pursue an agricultural V.E.T. education. Consequently, this paper explores young peoples’ motivational regulation for engaging with agricultural education to provide a nuanced understanding of the internal processes guiding the decision-making process among this cohort of learners.

Methodology

This study was conducted in Ireland, consisting of 28 in-depth, semi-structured interviews. A qualitative research approach was applied in this study to build an understanding of young peoples’ motivation towards an agricultural education.

A purposive sampling technique was used to select interviewees. This sampling technique supported the identification of information-rich sources willing to participate and articulate meaningful, sensitive experiences and opinions regarding agricultural education motivation (Bernard Citation2017; Creswell and Clark Citation2018). Snowball sampling was used in tandem with purposive sampling procedures to recruit informants the researchers did not have direct access to. Five key actor groups were categorised for purposive sampling to identify appropriate informants within the field of agricultural V.E.T. education; these groups were: (i) national population of agricultural college principals (n = 6); (ii) sample of agricultural college teachers (n = 6); (iii) sample of full-time agricultural education students (n = 6); (iv) sample of agricultural education graduates (n = 6); and (v) sample of policy makers within agricultural education (n = 4). Each of these key actor groups are directly involved in the praxis of education. Policy makers identified in this study are directly involved in agricultural education policy formulation and implementation in Irish agricultural colleges, of which there are six. Agricultural education students identified were enrolled on a full-time Level 6 agricultural V.E.T programmeFootnote2 at the time of the study. Agricultural graduates had completed a Level 6 agricultural V.E.T. programme in the previous two years. An evenly distributed sample of participants was chosen given that teachers, students, organisations, and policy makers equally contribute towards the success of the teaching and learning environment (Kidane and Worth Citation2014). Therefore, understanding motivation to pursue an agricultural education from each of these perspectives was deemed important within the context of the teaching and learning nexus.

The research presented in this paper is part of a larger project which investigated agricultural education from the perspective of the teaching and learning context. Consequently, other stakeholders indirectly involved in agricultural education, such as family and community members, were not involved in the study. This paper focuses on how external and internal factors regulate motivation using an analytical framework derived from S.D.T. to understand young peoples’ motivation for engaging in agricultural education (). In particular, the motivational regulations (i.e. external, introjected, identified, integrated regulation) from S.D.T. were adopted as a critical lens to identify these factors. Other studies employed a quantitative approach to the collection of data regarding student motivation (Charatsari, Lioutas, and Koutsouris Citation2017; Inegbedion and Islam Citation2020; Yasué, Kirkpatrick, and Davison Citation2020). This study aimed to provide an understanding of the motivation for engaging with agricultural education, using a qualitative approach that sought to explore, as opposed to confirm, motivational regulation towards an agricultural education. This supported an in-depth exploration of the study phenomenon. Such a qualitative approach has been applied by other researchers examining motivation through the lens of S.D.T (Hancox et al. Citation2018; Kinnafick, Thøgersen-Ntoumani, and Duda Citation2014; White et al. Citation2020; Wood Citation2019).

All face-to-face semi-structured interviews conducted were audio-recorded and subsequently transcribed verbatim by the first author. Thematic analysis was used to analyse this qualitative data using inductive and deductive approaches for coding and the identification of themes, using the analytical framework derived from S.D.T. Thematic analysis was applied given its flexibility in facilitating an exploration of how unique personal experiences are understood (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). Data collected were separated, analysed, and synthesised using qualitative coding (Enosh, Tzafrir, and Stolovy Citation2015).

An inductive approach was applied to explore themes arising from the data (i.e. variety of reasons for engaging in agricultural education e.g. financial, family expectation, etc.).

A deductive approach was used to categorise the reasons for engaging in agricultural education within the S.D.T. (e.g. specific motivational regulations: external regulation, introjected regulation, identified regulation, integrated regulation).

Open coding was applied to inductively identify codes within the dataset.

Axial coding was used to inductively create subcategories within the dataset, i.e. individual motivation for engaging with agricultural education (e.g. financial incentive, succession and inheritance, family expectation, love for farming, etc.).

Finally, subcategories identified were deductively integrated into broader categorisations based on the S.D.T. (i.e. external regulation, introjected regulation, identified regulation, integrated regulation).

Concepts occurring in-text were identified, patterns occurring were analysed, and any associations between themes were identified and recorded accordingly. Transcripts were reread multiple times by the authors to refine the coding approach and the categories identified were discussed between authors to ensure they were reflective of the patterns in the data.

Results and discussion

Young peoples’ motivation for engaging in agricultural education can be captured within S.D.T. as a taxonomy of human motivation. Reasons for entering agricultural education are classified into categories focused on motivational regulations as illustrated in the analytical framework. This section will outline each of these categories in relation to young peoples’ motivational regulation towards an agricultural education.

External regulation

Political measures were introduced at the European level to encourage more young people to pursue a career within the farming industry (European Commission Citation2013). The aim and purpose of this measure was to provide support to the establishment of new farms and alleviate the ‘young farmer problem’ across Europe. In the Irish case, such policy instrumentation resulted in a surge in numbers enrolling on agricultural programmes (Teagasc Citation2021) as young people embarked on a journey towards young trained farmer status1, which is commonly known as the ‘Green Cert’, and will be referred to as such here in. In this study, it was acknowledged that mandatory possession of the ‘Green Cert’ to avail of financial incentives resulted in a surge in numbers attending V.E.T. agricultural colleges to obtain young, trained farmer status.1 The introduction of this financial incentive had implications for extrinsic regulation of young peoples’ motivation, within farming communities, to engage with agricultural education. A notable proportion of the student population in V.E.T. agricultural colleges in Ireland pursued an agricultural qualification as a result of the financial incentives associated with the qualification. College teachers, agricultural graduates, and full-time students alluded to extrinsic regulation as a motivator for pursuing an agricultural education:

Unfortunately, a lot of the students come in with the motivation of getting a certificate to maximise [access to] schemes (I17 College Teacher)

… they want the ‘Green Cert’. If there was no ‘Green Cert’ they wouldn’t be here and they expect you to just give them the ‘Green Cert’ (I16 College Teacher)

For some of them they will see merit only in the award from the point of view of being a customer of the Department and getting grants (I3 College Teacher)

… they have no interest, they’re incredibly hard to motivate (I16 College Teacher)

It is very much up to the educator when you’re inside the classroom to actually make students interested in the topic or let them see merit in its own right … that [the financial incentives] might be the reason they’re there but that’s not good enough for us as educators to accept that as the baseline … it’s a case of something that’s very important to you over the next ten years in farming (I3 College Teacher)

Introjected and identified regulation

Young farmers are socially and psychologically influenced by family culture and expectation as farming is perceived as a way of life. The relationship of family farming with place (Downey, Threlkeld, and Warburton Citation2017) and genealogical attachments to land and place (Low Citation1992) have led to the continuance of inter-generational family farming. These non-monetary values and the culture of farming are regulating young peoples’ motivation for pursuing an agricultural education, highlighting the influence of socio-emotional wealth and the introjected motivation accompanying this wealth:

There’s still very much the family farm syndrome, I’m from a farm therefore I’m going to become a farmer (I22 College Principal)

It’s kind of an expectation within the family and part of it is because of individual desires and this is the life they see for themselves (I28 Policy Maker)

… often they’ll [young people] come here [V.E.T agricultural college] because there’s a farm at home. It’s not that they have great ambitions for it but they are expected to take over the farm (I1 College Principal)

It’s strong, the bloodlines or genetic lines that make up farming; am I going to be the generation that closes this place, that sells this place? To a certain extent maybe it’d be right if it was sold but the vast majority of people will struggle along (I2 College Teacher)

With regard to identified regulation, gender appears to have an influence on a young person’s motivation for pursuing an agricultural education. Identified regulation was repeatedly mentioned as a form of intrinsic regulation for females by college principals and policy makers within this study. These groups suggested agricultural education at the V.E.T. level provides a steppingstone to higher education (H.E.) for females, presenting opportunities for a career outside farming:

Girls probably do better at second level so they often go to higher education … higher expectations (I28 Policy Maker)

Females tend to go to colleges like University College Dublin to do agricultural science (I26 Policy Maker)

The smarter girls don’t come to agricultural college. That’s not to say that they’re not pursuing an agricultural qualification in University College Dublin, Tralee Institute of Technology, Waterford Institute of Technology, etc. (I23 College Principal)

Previously, it was mentioned that the culture and expectation of the farm family contributes to introjected regulation. Although, whilst the inter-generational family farming model still very much exists, the succession and inheritance model within farming is changing. Traditionally, the family farm was gifted to the eldest son within the family unit (Grubbström, Stenbacka, and Joosse Citation2014) but nowadays, and certainly within this study, this is not the traditional case:

A lot of them [farmers] are lucky if they get one son interested, so I think they’d be happy if they got one rather than picking and choosing who inherits (I21 Agricultural Graduate)

Most of my friends that’d be in farming, they’re not always the oldest one. I’m the second oldest and it’s just whoever is the most interested that usually takes it up (I20 Agricultural Graduate)

… very naturally maybe a successor was identified, who just showed a huge interest in the farm and wanted to farm (I27 Policy Maker)

It’s hard, labour-intensive work and I suppose the status quo was that the eldest son gets the farm (I10 College Teacher)

There’s a reason why men don’t play against women in rugby and it’s the same with farming, it’s a physical, tough career (I1 College Principal)

… it may be a cultural thing that agricultural college is seen as for boys and lads actually and that maybe people might be less comfortable going into that environment (I28 Policy Maker)

Finally, external regulation discussed previously was also closely associated with identified regulation within this study in terms of a young person’s motivation to pursue an agricultural education. The findings suggest that the financial incentive perhaps also supports autonomous intrinsic motivation as a young person potentially recognises and appreciates the value of an agricultural education from the perspective of obtaining agricultural grants and benefiting from increased basic payments annually under C.A.P. Pillar I payments. Agricultural graduates within this study referred to external and identified regulation:

It’s solely for the ‘Green Cert’ and the big one is stamp duty exemption (I7 Agricultural Graduate)

I think there are a small percentage of farmers who are students that are there to learn and become better farmers. The vast majority of them are there to get the piece of paper that will entitle them to grants and that’s where the whole structure is wrong because that should not be your motive to go to college (Interviewee 13 Agricultural Graduate)

Identified regulation for agricultural graduates focuses on the value of an agricultural education in terms of competence, a belief in their ability to apply best practice at farm level. A similar observation was made within the full-time students’ excerpts regarding motivation to pursue an agricultural education:

My goal was to get the ‘Green Cert’ but you also learn all the practical skills and how to do everything correctly (I5 Agricultural Student)

This student makes reference to competence and the value of education with regard to best practice. Within these excerpts, respondents are exhibiting controlled motivation in terms of external regulation, however, the value and significance of an agricultural education is still acknowledged and recognised in the form of identified regulation despite the initial motivation to pursue agricultural education.

Integrated regulation

Integrated regulation is apparent to a lesser extent than the previous regulations outlined above. In this study, it was closely associated with the other forms of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation mentioned thus far. It is suggested the majority of young people participating in agricultural V.E.T. education are male, descending from a farming background:

The majority, 95% of them [young people], are coming from the home farm. They have a background in agriculture and I would say 50% of them are hoping to pursue that interest in agriculture whether it be on the home-farm full-time, or perhaps part-time farming with an off-farm job, and then the remainder would be part-time farmers working full-time in a non-agricultural career. (I17 College Teacher)

In a lot of cases they’ve either grown up on a farm or they’ve worked on a farm. They’re practical learners, they’re kinaesthetic learners, they like to learn practically and they like being outdoors (I27 Policy Maker)

You genuinely have an interest in it [farming]. If you don’t have an interest in farming you’re not going to put in the work and the hours that’s needed for it (I20 Agricultural Graduate)

You have students that are interested and want to better the home farm, better themselves, and make it somewhat financially viable (I10 College Teacher)

The females that come in are exceptionally well equipped in terms of skills, knowledge, and competence so they selected a career in agriculture (I27 Policy Maker)

Conclusions and recommendations

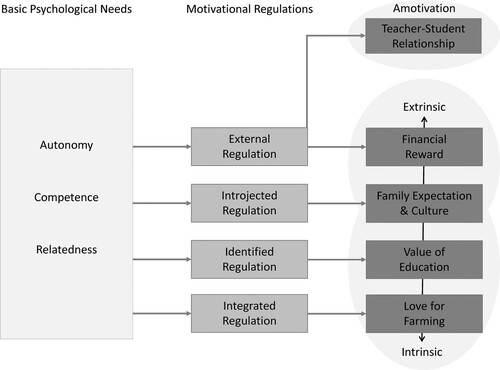

The findings of this study provide an understanding of the motivational regulations which mobilise young people to engage in agricultural education. Within the Irish context, numbers enrolling on agricultural V.E.T. programmes have dramatically increased over recent years (Teagasc Citation2021), largely due to the provision of young trained farmer status and the financial benefits associated with this status with regard to C.A.P. Pillar I payments. This represents positive progression in terms of upward mobility for the future generation of young farmers. However, understanding motivation for engagement in agricultural education is important in terms of the teaching and learning nexus. Based on the findings presented within this paper, young peoples’ motivation for engaging in agricultural education can be captured within the motivational regulations of the S.D.T. (). This sheds light on the psychological process that energises an individual to embark on such a journey.

Figure 2. External and internal factors regulating motivation for engaging in agricultural education.

Autonomous and controlled forms of extrinsic and intrinsic regulation are identified within this study as motivation for young peoples’ engagement with agricultural education. Fully internalised, intrinsic regulation is largely absent in terms of motivation leading to young peoples’ engagement in agricultural education. However, that said, integrated regulation with regard to the farm family’s identification of a son/daughter to engage in agricultural education features within participants excerpts. Extrinsic and intrinsic regulation in the form of external, introjected, and identified regulation featured as motivational regulations for young peoples’ engagement in agricultural education within this paper. Competence featured as motivating students towards engaging with agricultural education. Evidence of external and introjected regulations exhibited controlled motivation, external to the self, mainly in the form of a financial reward and shame/guilt avoidance regarding farm family culture and expectation. However, autonomous motivation in the form of identified regulation, and to a much lesser extent integrated regulation, also became apparent as motivational regulations for engagement in agricultural education. These findings are in line with a study conducted by Inegbedion and Islam (Citation2020) which found identified and integrated regulation to be the two most dominant motivational drivers for students to study agricultural courses. However, contrary to this paper, external regulation was not a motivational driver within Inegbedion and Islam (Citation2020)’s study. Indeed, external regulation was deemed to have a negative factor loading resulting in demotivation. Within this paper, external regulation featured as a motivational regulation for young people engaging in agricultural education, however, the impact of external regulation on the teaching and learning nexus and the challenges facing educators as a result was alluded to in terms of the increasing importance of competence and relatedness within the teaching and learning environment. Subsidies themselves have been proven as problematic market interventions which frequently result in unintended consequences (Cowe Citation2012). Within this paper, it could be argued that external regulation, such as the financial incentive associated with the ‘Green Cert’, is resulting in increased numbers of young people being motivated to engage in agricultural education and that agricultural education is merely becoming an extension of agricultural policy interventions. However, the aging farmer population, documented as a ‘young farmer problem’ in the literature (Zagata and Sutherland Citation2015), presents an important challenge to the future of farming communities given the importance of young farmers to the future of farming (Brennan et al. Citation2016) and the significance of generational renewal to the longer-term survival of these communities. Therefore, external regulation of young peoples’ motivation to engage in agricultural education may be a welcomed approach in this instance. However, it must be acknowledged that external regulation can undermine intrinsic motivation in educational settings (Charatsari, Lioutas, and Koutsouris Citation2017), which presents a noteworthy challenge for the agricultural education sector. Lack of intrinsic motivation in the decision-making process to acquire qualifications can result in disinterested, unmotivated students, not willing to engage fully with the teaching and learning process, taking for granted the value and worth of a formal agricultural education to the success of future farming practices within a hugely challenging sector. Thus, whilst the introduction of a financial incentive is helping alleviate the ‘young farmer problem’, the impact of such an incentive on individual motivation is not without concern given its impact on intrinsic motivation.

In addition to external regulation, less controlled and more autonomous forms of both extrinsic and intrinsic regulation also featured within participant excerpts in this study. Introjected and identified regulation relating to family culture and expectation and appreciated value of agricultural education engagement are evident within this paper. Non-monetary values associated with the culture of farming such as the relationship of farming with place, genealogical attachments to land and place, and the inter-generational family farming model present forms of introjected regulation which are highly controlled motivation for engaging in agricultural education. To avoid ‘letting down’ the family, often young people feel the pressure to choose agricultural education to avoid shame/guilt which may be associated with expressed interest in alternative education pathways or career aspirations. Other studies also allude to parents and peers as motivators for students’ choice to study agriculture (Fizer Citation2013; Rayfield et al. Citation2013). However, that said, interestingly, the succession and inheritance model in farming is changing. The farm family now identifies the young person within the family unit who is most interested in a future career within the farming sector as the individual to obtain a formal agricultural qualification. This represents integrated regulation on the part of the farm family as the decision is exclusively internal and highly autonomous. For the young person within the family unit, identified regulation motivates them as they appreciate and recognise the value of an agricultural education in terms of competence and perhaps also in terms of financial currency associated with a formal agricultural qualification. This somewhat supports autonomy towards intrinsic motivation which is largely absent with introjected regulation alone. Individuals motivated by identified regulation are more likely to continue a behaviour and persist with a task in the absence of external support (Lavigne, Vallerand, and Miquelon Citation2007; Ryan and Deci Citation2017), thus counteracting the negatives associated with external and introjected regulation. These findings are noteworthy given there is little to no evidence on the motivational influence of identified regulation in the context of agricultural education documented within the literature. Individual needs for competence motivated young people to engage in agricultural education. Identified regulation stemming from family culture and expectation as mentioned above, as well as gender decisions and the motivation for non-agricultural background students offer valuable insights into the psychological processes energising young people to engage in agricultural education. College principals and policy makers within this study suggested females enter agricultural V.E.T. education as a steppingstone to H.E. with their sights set on careers outside farming. It’s suggested this is historical and cultural as V.E.T. agricultural colleges are ‘seen as for boys’, but consideration needs to be given to the role of the female inside the farm gate. Often, females have different roles within the farm family (Zaridis, Rontogianni, and Karamanis Citation2015) with needs and interests also differing to their male counterparts (Bock Citation2004). They are often considered an invisible force (Charatsari Citation2014) where their work is seasonal, part-time, and unpaid (Tsiaousi and Partalidou Citation2021). Women consider themselves as helpers and housewives due to social-family norms where their contribution on farm is deemed contributory as opposed to empowering (Balaine Citation2019). Although this study did not examine females’ role on-farm and its potential impact on the motivation to engage in agricultural education, consideration should be given to the role and function of agricultural education programmes – does the ‘Green Cert’ (or similar programmes) equip women for these roles? Further research is needed to establish whether agricultural education programmes are designed for women in farming in terms of the programme’s role, function, and overall objective.

The motivational regulations identified in this paper, combined with an array of academic and practical abilities within a student group, presents a significant challenge to educators and education providers in terms of engagement, promotion of sustainable practice, and the ability to change mind-set and broaden horizons. In a system where controlled regulation is a motivator for young peoples’ engagement in agricultural education, there is a requirement for autonomy-supportive teachers in the creation of learning environments conducive to learner construction of knowledge based on both new and previous learnings and experiences. A challenging task for agricultural education programme designers is the provision of agricultural education programmes which facilitate internalisation of extrinsic motivation given young peoples’ motivation for engaging in agricultural education in the first instance. S.D.T. scholars believe more intrinsically motivated learners achieve higher levels of learning outcomes (Deci and Ryan Citation1991; Ryan and Deci Citation2017). Therefore, learning environments which create active, collaborative, peer-to-peer learning opportunities which challenge students’ abilities and intellect regarding agricultural practices is required to enhance student engagement and motivation for participation once the decision is made to engage in agricultural education. As mentioned previously, external and introjected regulation can diminish intrinsic motivation in the educational setting and so teaching and learning strategies which promote autonomous forms of intrinsic motivation become imperative. Consequently, problem-based learning as an educational approach deserves some attention (Rotgans and Schmidt Citation2012). The findings within this study have significant implications for relevant policies and interventions regarding agricultural education. The establishment of an educational philosophy at the policy level and a teaching philosophy at the individual educator level becomes important in this instance, as it will influence the alignment of instructional techniques with both formative and summative assessment. In this context, a shift away from the traditional, teacher-centred approach to teaching and learning towards a student-centred learning environment where the teacher acts as a facilitator of knowledge exchange becomes imperative. Incorporating the student voice is important in an environment where different motivational regulations are present within a diverse group of learners in terms of academic and practical ability. In this instance it becomes significantly important for policy makers and scholars to nuance the understanding of young peoples’ motivation for engaging with agricultural education. An understanding of the motivational regulations involved in the decision-making processes regarding professional life and future achievement is crucial to policy makers in terms of promoting and marketing education programmes. The relevance of a training programme to the needs and objectives of an individual have been shown to influence individual’s decisions to engage in agricultural extension, education, or training activities (Charatsari, Lioutas, and Koutsouris Citation2017; Murray-Prior, Hart, and Dymond Citation2000). Subsequently, from the perspective of gender, the female’s role inside the farm gate, and the overall objective of agricultural education, further research is required to explore the extent to which agricultural education programmes meet females’ needs. Additionally, agricultural education curriculum development policy makers should consider the establishment of self-governed learning frameworks which enhance young peoples’ autonomous self-regulation. This is an important consideration given that encouragement of self-direction is important in facilitating intrinsic motivation (Charatsari, Lioutas, and Koutsouris Citation2017). Cultural and economic factors such as family and financial support influence career choice (Lent, Brown, and Hackett Citation2002) while parents from farming backgrounds are more likely to encourage their son(s)/daughter(s) to pursue careers in farming (Beecher et al. Citation2019), and subsequently an agricultural education. This will foster the continuation of the stereotypical perception that farming is a male occupation with agricultural V.E.T. education being predominantly for males. However, this paper presents opportunities for gradual change as females view agricultural V.E.T. education as a steppingstone to H.E. Thus, beyond the individual and their motivation for participation in agricultural education, educating parents and communities is essential in leading informed decisions and policies around agricultural education. Exposure to the realities of agricultural education will help challenge the stereotypes and perhaps support self-direction which in turn can help facilitate intrinsic motivation. In essence, understanding the motivation of young people and their motivational regulation for engaging in agricultural education is essential as young farmers are crucial for generational renewal and the facilitation of innovation and growth within the farming sector. The agricultural education sector needs to change/adapt and promote itself to a wider audience, including those from non-agricultural backgrounds, parents, and communities. There is a need for innovation in attracting young people towards agricultural education to ensure high quality recruits, intrinsically motivated to engage in agricultural education. This will help in addressing the current challenge facing agricultural educators and education providers, i.e. facilitating internalisation of extrinsic motivation given young peoples’ motivation for engaging in agricultural education in the first instance.

Although this paper demonstrates young peoples’ motivational regulation for engaging with agricultural education, there are some limitations to the study which are worth mentioning, as they highlight areas for further investigation. The research presented is part of a larger project which focused on agricultural education from the teaching and learning perspective. Thus, family and community members weren’t included in the sample population. However, given the cultural importance of place and community and their influence on career choice, further research should include these groups in exploring further the motivational regulations for engaging in agricultural education from their perspectives. The findings in this paper suggest integrated regulation is closely associated with the other forms of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation present. Subsequently, future studies involving family and community members have the potential to contribute to understanding the influence of this motivational regulation on agricultural education engagement further. Additionally, a small sample of students were selected for this study, alongside other key actor groups as mentioned in the methodology, given their involvement in the praxis of education. Further studies may use a larger student sample population to add to the discussion presented within this paper, particularly in relation to the different types of motivational regulations present. Despite the limitations, the significant contribution of this paper to existing needs and priorities within V.E.T. policy and research lies in the pragmatic insights which demonstrate the importance of understanding young peoples’ motivational regulation towards engagement in agricultural education. This paper supports an understanding of the external and internal factors which regulate young peoples’ motivation for engaging in agricultural education through the lens of S.D.T.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sinéad Flannery

Dr. Sinéad Flannery is an Assistant Professor in Behavioural Science in Agriculture in the School of Agriculture and Food Science, University College Dublin. Sinéad’s key areas of interest are agricultural education, farmer behaviour change, and farm health, welfare and safety.

Karen Keaveney

Dr. Karen Keaveney is an Assistant Professor and Head of Rural Development in the School of Agriculture and Food Science, University College Dublin. Previously, Karen was a Lecturer in Rural Spatial Planning in Queen’s University Belfast and has held a number of visiting appointments internationally. Karen’s key areas of interest are rural planning, housing and development, and agricultural education.

Frank Murphy

Frank Murphy is Head of the Teagasc Curriculum Development and Standards Unit based at Kildalton College, Co Kilkenny, Ireland. Prior to taking up this post, he was Principal of Kildalton College coordinating Further Education and Training (FET) courses. He has recently been steering the development of land-based apprenticeship programmes.

Notes

1 This refers to the successful completion of a Level 6 N.F.Q. qualification in agriculture which entitles the trained individual to a 25% top-up on their annual basic payment received from the national government and European Union under C.A.P. Pillar I payments.

2 Level 6 on the N.F.Q. is equivalent to Level 5 on the E.Q.F. Graduates of V.E.T. programmes obtain a Certificate level of training.

3 Level 7 and 8 on the Irish N.F.Q. is equivalent to Level 6 on the E.Q.F.

References

- Balaine, L. 2019. “Gender and the Preservation of Family Farming in Ireland.” EuroChoices 18 (3): 33–37.

- Ball, C., K.-T. Huang, S. R. Cotten, R. V. Rikard, and L. O. Coleman. 2016. “Invaluable Values: An Expectancy-Value Theory Analysis of Youths’ Academic Motivations and Intentions.” Information, Communication & Society 19 (5): 618–638. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2016.1139616.

- Beecher, M., M. Gorman, P. Kelly, and B. Horan. 2019. “Careers in Dairy: Adolescents Perceptions and Attitudes.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 25 (5): 415–430. doi:10.1080/1389224X.2019.1643745.

- Bernard, H. R. 2017. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Bock, B. B. 2004. “Fitting in and Multi-Tasking: Dutch Farm Women's Strategies in Rural Entrepreneurship.” Sociologia Ruralis 44 (3): 245–260.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101.

- Brennan, N., M. Ryan, T. Hennessy, and P. Cullen. 2016. “The Impact of Farmer age on Indicators of Agricultural Sustainability.” FLINT Deliverable D5.2H: 9–34.

- Cassidy, A. 2019. “Female Successors in Irish Family Farming: Four Pathways to Farm Transfer.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies/Revue Canadienne D'études du Développement 40 (2): 238–253.

- Charatsari, C. 2014. “Is This a Man’s World? Woman in the Farm Family of Thessaly, Greece from the 1950s Onwards.” Gender Issues 31 (3): 238–266.

- Charatsari, C., E. D. Lioutas, and A. Koutsouris. 2017. “Farmers’ Motivational Orientation Toward Participation in Competence Development Projects: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 23 (2): 105–120.

- Cowe, R. 2012. “Why Farm Subsidies Don't Always Achieve the Results Intended.” The Guardian. Accessed 14th October. https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/farm-subsidies-unintended-consequences.

- Creswell, J. W., and V. L. P. Clark. 2018. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Washington DC: Sage Publications.

- Cush, P., and Á Macken-Walsh. 2016. “Farming ‘Through the Ages: Joint Farming Ventures in Ireland.” Rural Society 25 (2): 104–116.

- Deci, E. L., H. Eghrari, B. C. Patrick, and D. R. Leone. 1994. “Facilitating Internalization: The Self-Determination Theory Perspective.” Journal of Personality 62 (1): 119–142.

- Deci, E. L., and A. C. Moller. 2005. “The Concept of Competence: A Starting Place for Understanding Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determined Extrinsic Motivation.” In Handbook of Competence and Motivation, edited by A. J. Elliot and C. S. Dweck, 579–597. New York: Guilford Publications.

- Deci, E. L., and R. M. Ryan. 1991. “A Motivational Appraoch to Self: Integration in Personality.” In Nebraska Symposium on Motivation: Perspectives on Motivation, edited by R. Dienstbier, 237–288. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Deci, E. L., and R. M. Ryan. 2012. “Motivation, Personality, and Development Within Embedded Social Contexts: An Overview of Self-Determination Theory.” In The Oxford Handbook of Human Motivation, edited by R. M. Ryan, 85–107. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Downey, H., G. Threlkeld, and J. Warburton. 2017. “What is the Role of Place Identity in Older Farming Couples’ Retirement Considerations?” Journal of Rural Studies 50: 1–11.

- Duesberg, S., P. Bogue, and A. Renwick. 2017. “Retirement Farming or Sustainable Growth–Land Transfer Choices for Farmers Without a Successor.” Land Use Policy 61: 526–535.

- Enosh, G., S. S. Tzafrir, and T. Stolovy. 2015. “The Development of Client Violence Questionnaire (CVQ).” Journal of Mixed Methods Research 9 (3): 273–290.

- European Commission. 2013. “Overview of CAP Reform 2014-2020.” Agricultural Policy Perspectives Brief No 5, December 2013.” Accessed 14th June. https//ec.europa.eu/agriculture/sites/agriculture/files/policy-perspectives/policy-briefs/05_en.pdf.

- Eurostat. 2021. “Young People in Farming.” Accessed 15th November. https://ec.europa.eu/info/food-farming-fisheries/key-policies/common-agricultural-policy/income-support/young-farmers_en.

- Feder, G., R. Murgai, and J. B. Quizon. 2004. “Sending Farmers Back to School: The Impact of Farmer Field Schools in Indonesia.” Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy 26 (1): 45–62.

- Fizer, D. 2013. “Factors Affecting Career Choices of College Students Enrolled in Agriculture.” MSc, A research paper presented for the Master of Science in Agriculture and Natural Science degree at The University of Tennessee. Martin, University of Tennessee.

- Gibson, S. C. 2018. ““Let’s go to the Park.” An Investigation of Older Adults in Australia and Their Motivations for Park Visitation.” Landscape and Urban Planning 180: 234–246.

- Grubbström, A., S. Stenbacka, and S. Joosse. 2014. “Balancing Family Traditions and Business: Gendered Strategies for Achieving Future Resilience among Agricultural Students.” Journal of Rural Studies 35: 152–161. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2014.05.003.

- Guay, F. 2022. “Applying Self-Determination Theory to Education: Regulations Types, Psychological Needs, and Autonomy Supporting Behaviors.” Canadian Journal of School Psychology 37 (1): 75–92. doi:10.1177/08295735211055355.

- Hamilton, W., G. Bosworth, and E. Ruto. 2015. “Entrepreneurial Younger Farmers and the “Young Farmer Problem” in England.” Agriculture and Forestry 61 (4): 61–69.

- Hancox, J. E., E. Quested, N. Ntoumanis, and C. Thøgersen-Ntoumani. 2018. “Putting Self-Determination Theory Into Practice: Application of Adaptive Motivational Principles in the Exercise Domain.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 10 (1): 75–91.

- Herzfeld, T., and R. Jongeneel. 2012. “Why do Farmers Behave as They do? Understanding Compliance with Rural, Agricultural, and Food Attribute Standards.” Land Use Policy 29 (1): 250–260.

- Howard, J., M. Gagné, A. J. Morin, and A. Van den Broeck. 2016. “Motivation Profiles at Work: A Self-Determination Theory Approach.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 95: 74–89.

- Inegbedion, G., and M. M. Islam. 2020. “Youth Motivations to Study Agriculture in Tertiary Institutions.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 26 (5): 497–512.

- Kidane, T., and S. Worth. 2014. “Student Perceptions of Agricultural Education Programme Processes at Selected High Schools in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 20 (4): 381–396.

- Kinnafick, F.-E., C. Thøgersen-Ntoumani, and J. L. Duda. 2014. “Physical Activity Adoption to Adherence, Lapse, and Dropout: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective.” Qualitative Health Research 24 (5): 706–718.

- Lavigne, G. L., R. J. Vallerand, and P. Miquelon. 2007. “A Motivational Model of Persistence in Science Education: A Self-Determination Theory Approach.” European Journal of Psychology of Education 22 (3): 351–369.

- Lent, R. W., S. D. Brown, and G. Hackett. 2002. “Social Cognitive Career Theory.” Career Choice and Development 4 (1): 255–311.

- Leonard, B., A. Kinsella, C. O’Donoghue, M. Farrell, and M. Mahon. 2017. “Policy Drivers of Farm Succession and Inheritance.” Land Use Policy 61: 147–159. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.09.006.

- Low, S. M. 1992. “Symbolic Ties That Bind: Place Attachment in the Plaza.” In Place Attachment, edited by I. Altman and S. M. Low, 165–185. New York: Plenum Press.

- May, D., S. Arancibia, K. Behrendt, and J. Adams. 2019. “Preventing Young Farmers from Leaving the Farm: Investigating the Effectiveness of the Young Farmer Payment Using a Behavioural Approach.” Land Use Policy 82: 317–327.

- McKillop, J., K. Heanue, and J. Kinsella. 2018. “Are all Young Farmers the Same? An Exploratory Analysis of on-Farm Innovation on Dairy and Drystock Farms in the Republic of Ireland.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 24 (2): 137–151.

- Murray-Prior, R., D. Hart, and J. Dymond. 2000. “An Analysis of Farmer Uptake of Formal Farm Management Training in Western Australia.” Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture 40 (4): 557–570.

- NAAE. 2021. What is Agricultural Education?”, Accessed 12th November 2021. https://www.naae.org/whatisaged/.

- Nix, G. A., R. M. Ryan, J. B. Manly, and E. L. Deci. 1999. “Revitalization Through Self-Regulation: The Effects of Autonomous and Controlled Motivation on Happiness and Vitality.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 35 (3): 266–284.

- Ortiz, O., K. Garrett, J. Health, R. Orrego, and R. Nelson. 2004. “Management of Potato Late Blight in the Peruvian Highlands: Evaluating the Benefits of Farmer Field Schools and Farmer Participatory Research.” Plant Disease 88 (5): 565–571.

- Payne, S. M., P. Nicholas-Davies, and R. Home. 2019. “Harnessing Implementation Science and Self-Determination Theory in Participatory Research to Advance Global Legume Productivity.” Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 3: 62.

- Pinder, C. C. 1998. Motivation in Work Organisations. New Jersey: Upper Saddle River.

- Rayfield, J., T. P. Murphrey, C. Skaggs, and J. Shafer. 2013. “Factors That Influence Student Decisions to Enroll in a College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.” NACTA Journal 57 (1): 88–83.

- Rotgans, J. I., and H. G. Schmidt. 2012. “Problem-based Learning and Student Motivation: The Role of Interest in Learning and Achievement.” In One-day, one-Problem, edited by G. O'Grady, E. Yew, K. Goh, and H. Schmidt, 85–101. Singapore: Springer.

- Ruzek, E. A., and K. Schenke. 2019. “The Tenuous Link Between Classroom Perceptions and Motivation: A Within-Person Longitudinal Study.” Journal of Educational Psychology 111 (5): 903–917. doi:10.1037/edu0000323.

- Ryan, R. M., and E. L. Deci. 2017. Self-determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness. New York: Guilford Publications.

- Ryan, R. M., and C. P. Niemiec. 2009. “Self-determination Theory in Schools of Education: Can an Empirically Supported Framework Also be Critical and Liberating?” Theory and Research in Education 7 (2): 263–272. doi:10.1177/1477878509104331.

- Teagasc. 2021. Teagasc Opening Statement on Teagasc Education and Training to the Oireachtas Committee on Agriculture Food and the Marine.” Accessed 12th November. https://www.teagasc.ie/media/website/publications/2021/Teagasc-Opening-Statement-on-Teagasc-Education-and-Training-to-the-Oireachtas-Committee-on-Agriculture-Food-and-the-Marine.pdf.

- Tomlinson, J., and K. Rhiney. 2018. “Assessing the Role of Farmer Field Schools in Promoting pro-Adaptive Behaviour Towards Climate Change among Jamaican Farmers.” Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences 8 (1): 86–98.

- Tsiaousi, A., and M. Partalidou. 2021. “Female Farmers in Greece: Looking Beyond the Statistics and Into Cultural–Social Characteristics.” Outlook on Agriculture 50 (1): 55–63.

- Vanslembrouck, I., G. Van Huylenbroeck, and W. Verbeke. 2002. “Determinants of the Willingness of Belgian Farmers to Participate in Agri-Environmental Measures.” Journal of Agricultural Economics 53 (3): 489–511.

- White, R. L., A. Bennie, D. Vasconcellos, R. Cinelli, T. Hilland, K. B. Owen, and C. Lonsdale. 2020. “Self-determination Theory in Physical Education: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies.” Teaching and Teacher Education 99: 103247.

- Wood, R. 2019. “Students’ Motivation to Engage with Science Learning Activities Through the Lens of Self-Determination Theory: Results from a Single-Case School-Based Study.” Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science & Technology Education 15 (7): 1–22.

- Wynne-Jones, S. 2017. “Understanding Farmer co-Operation: Exploring Practices of Social Relatedness and Emergent Affects.” Journal of Rural Studies 53: 259–268.

- Yasué, M., J. B. Kirkpatrick, and A. Davison. 2020. “Meaning, Belonging and Well-Being.” Conservation & Society 18 (3): 268–279.

- Zagata, L., and L.-A. Sutherland. 2015. “Deconstructing the ‘Young Farmer Problem in Europe’: Towards a Research Agenda.” Journal of Rural Studies 38: 39–51.

- Zaridis, A. D., A. Rontogianni, and K. Karamanis. 2015. “Female Entrepreneurship in Agricultural Sector. The Case of Municipality of Pogoni in the Period of Economic Crisis.” Journal of Research in Business, Economics and Management 4 (4): 486–497.

- Zhou, M., K. K. Chan, and T. Teo. 2016. “Modelling Mathematics Teachers’ Intention to Use the Dynamic Geometry Environments in Macau: An SEM Approach.” Educational Technology & Society 19 (3): 181–193.