ABSTRACT

Purpose

Innovations in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are essential for increasing resource efficiency and sustainability in the agri-food system. An innovation support service (ISS) can benefit SMEs but the provision and access to it can be restricted across national borders thereby hindering cross-border regions’ economic potential. The aim was to investigate how ISSs are provided and used in such a region and explore stakeholders’ perceptions on their limitations and opportunities.

Methodology

We conducted a case study in the Dutch-German cross-border region Euregio Rhine-Waal which included a content analysis of websites and stakeholder interviews.

Findings

The provision of ISSs was limited by differing structures and priorities in both countries. SMEs’ unfamiliarity with responsible authorities, significant administrative effort, and uncertainty about pay-offs were perceived as factors limiting ISS.

Practical implications

We provide recommendations on how to improve ISS in cross-border regions and inform policymaking for cross-border regional development. We recommend reducing limitations of ISS provision and use, e.g. by engaging ISS providers and users in a co-creative approach. Furthermore, we suggest using opportunities of ISS provision and use, e.g. through increased promotion of available ISS by brokers.

Theoretical implications

Our research contributes to the literature of extension and advisory systems by showing how differing institutional settings, combined with different ‘innovation cultures’ and the availability of cross-border brokers affect cross-border integration of ISS.

Originality

This is the first study to explore the limitations and potentials of ISSs in a cross-border region.

Introduction

An increasing number of innovative activities under the European Union Programmes, such as the European Innovation Partnership, multi-actor networks, and cross-visits of farmers and advisors aim to enhance international collaborations and exchanges. These activities include deliberate policies and instruments to stimulate cross-border cooperation (Klerkx et al. Citation2017b; Fieldsend et al. Citation2021; Fieldsend et al. Citation2022). The European Union (including Norway, Switzerland and Liechtenstein) has a total of 40 internal borders (European Commission Citation2017). Despite the implementation of European Cohesion policy to strengthen cross-border regional integration since 1986/1988 (European Commission Citation2008; Manzella and Mendez Citation2009), the economic potential of border regions remains underdeveloped (Camagni, Capello, and Caragliu Citation2019).

Agriculture is often an important economic activity in rural cross-border regions. While farms can also be considered a sort of small- and medium-sized enterprises (SME) with a focus on agricultural primary production (Klerkx and Leeuwis Citation2008; Phillipson et al. Citation2004). SMEs exist along the whole agri-food value chain and operate providing goods and services for the broader agri-food system, including food and feed processing, fertilizer production, waste management, or logistics. Innovation is crucial for improving SMEs’ competitiveness and resource efficiency along the value chain as well as for decreasing negative environmental impacts from the agri-food system (European Commission Citation2019a). Simultaneously, economic development in cross-border regions can be achieved through fostering innovation in SMEs.

Multiple factors influence cross-border regional integration, including differing national interests and regional strategies regarding economic and institutional structure, knowledge infrastructures, and socio-cultural factors (Lundquist and Trippl Citation2013). These factors also influence how enterprises operate across the border and can be related to differences in innovative activities between countries (Neuberger et al. Citation2021). However, SMEs compared to large businesses tend to lack the resources and capacities to innovate (Nooteboom Citation1994; Narula Citation2004), which has also been noted for agri-food SMEs (e.g. Klerkx and Leeuwis Citation2008). For example, cooperation is important for innovation development, but prior research shows that SMEs struggle to develop strong networks even in a national context (Tödtling and Kaufmann Citation2002). Furthermore, collaboration within agricultural innovation networks is generally underfunded or impacted by fragmentation of actors in agri-food systems (Hermans, Klerkx, and Roep Citation2015). Both imply additional barriers in a cross-border context (Neuberger et al. Citation2021).

Innovation support services (ISS) can help enterprises to mobilize knowledge supply and demand (Proietti and Cristiano Citation2023). ISSs constitute the extension or advisory system within the broader Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation System (AKIS) and can be defined as immaterial and intangible goods aiming to facilitate innovation processes through knowledge and other capacities (Mathé et al. Citation2016). ISSs depend on providers such as research institutes and innovation funders and SMEs can use ISS for improving knowledge exchange and research, developing business strategies, using opportunities for networking and advanced training, and receiving advice on legal structures, market structures and financing (Kilelu et al. Citation2011; Galanakis Citation2006; Lundquist and Trippl Citation2013).

Different countries offer different forms of ISS (e.g. Knierim et al. Citation2017; Christoplos Citation2010; Rivera and Sulaiman Citation2009; Faure et al. Citation2019), and within national AKIS there are also diverse ISS systems active as part of so-called ‘micro-AKIS’ which form around the needs of different sorts of farmers or SMEs (Klerkx et al. Citation2017a; Sutherland and Labarthe Citation2022; Proietti and Cristiano Citation2023; Potters et al. Citation2022). Despite this variety, often national AKIS provides the broader institutional setting in which these ISS systems or micro-AKIS form and operate, such as regulations, standards, infrastructure, etc. (Fieldsend et al. Citation2022; Klerkx et al. Citation2017a). ISS and more broadly AKIS can be fragmented as (sometimes competing) service providers exist which can hamper enterprises’ access to the right ISS providers and optimal use of the diversity of ISS providers (Faure et al. Citation2019; Knierim et al. Citation2017; Prager, Creaney, and Lorenzo-Arribas Citation2017; Garforth et al. Citation2003; Proietti and Cristiano Citation2023). Cross-border ISS can offer benefits for those receiving it because they could potentially access a larger diversity of ISS. Providers can benefit by expanding their market and become more specialized/targeted for a bigger target group as SMEs from both sides of the border can access them equally (Proietti and Cristiano Citation2023). Consequently, also the national economies could benefit from spillover effects of the integration of innovation systems across the border. If enterprises benefit from innovation, their success induces, e.g. more production, more need for employees, etc., which also spills over to the neighboring country.

As agri-food enterprises outside of primary production might be less tied to a particular territory and more likely to operate internationally. Also, ISSs do not have to be bound to national borders as advisors have started to operate internationally (Klerkx Citation2020). It is likely that complexity of ISS provisioning increases in a cross-border setting: previous research shows that ISSs cannot be easily transferred from one country to another without adjustments. This is primarily due to the differences in the set-up of AKIS in terms of institutional frameworks, context-specific knowledge, approach of ISS to use either linear or interactive approaches, and innovation and collaboration ‘cultures’ (Klerkx and Guimón Citation2017; Klerkx et al. Citation2017b; Berdegué Sacristán Citation2001), which influence how innovation networks and ‘micro-AKIS’ form. Hence, ISSs are context specific and some can only be partially adapted to the setting of another country, such as in cross-border regions.

Based on earlier studies (Abdirahman, Cherni, and Sauvée Citation2014; Brink Citation2018; Faure et al. Citation2019; Knockaert, Vandenbroucke, and Huyghe Citation2013; van den Broek, Benneworth, and Rutten Citation2019), we argue that agri-food SMEs have different needs to develop their business in cross-border regions and to establish cross-border networks compared to SMEs operating only in the national context. Within the context of national AKISs, research has investigated how ISS can be improved for farmers (Kilelu, Klerkx, and Leeuwis Citation2014; Proietti and Cristiano Citation2023; Potters et al. Citation2022) and comparative research has been done on how multi-actor innovation partnerships adopt contrasting approaches to co-innovation depending on contextual contingencies within countries (Fieldsend et al. Citation2022). However, it is still unclear how ISS provision in cross-border settings is shaped and how their provision and use are matched. Therefore, calls have been made to unravel how international ISS systems operate across nations and what adaptations are required to enable successful functioning of ISSs in cross-border contexts (Klerkx Citation2020; Klerkx et al. Citation2017a). As Faure et al. (Citation2019) and Proietti and Cristiano (Citation2023) indicate, studying the relationship between the provider (e.g. private advisors, public extension agents, companies, or researchers) and the user (e.g. enterprises along the value chain, including farmers) of ISSs is central for a better understanding of how the system works. To the best of our knowledge, insights are missing on how the provision and use of ISSs is structured for agri-food SMEs in cross-border regions.

This research aims to investigate how ISS is provided and used in a cross-border region and simultaneously to explore stakeholders’ perception on their limitations and opportunities. This study contributes to extension and advisory systems’ literature by investigating the element of internationalization, i.e. how ISSs operate across borders (as suggested in Klerkx Citation2020) and contributes to the cross-border literature by providing empirical insights into the factors that enable and limit ISS provision in a selected case study regionFootnote1, i.e. the Dutch-German cross-border region Euregio Rhine-Waal. We first present the conceptual approach underpinning this research, which is followed by the presentation of the case study region and the description of the two research phases. The results and discussion sections are structured along the provision and use of ISS and the article finishes with a conclusion.

Conceptual framework

In this study, we explore what influences the provision and use of ISSs in a cross-border region. Therefore, the conceptual framework presents factors which can potentially influence innovation systems in cross-border regions and consequently how ISSs are provided and can be used. It helps to examine currently offered ISSs against previous findings and enrich the literature of extension and advisory systems toward limitations and opportunities of the cross-border ISS system (see discussion section).

Compared to a national context, different levels of cross-border regional integration cause specific challenges for ISS systems in a cross-border region, all of which influence the relationship between providers and users. Based on the reviewed literature, presents an overview of ISSs, aspects that define the level of cross-border regional integration and resulting factors that may influence the provision and use of ISS in a cross-border setting.

Table 1. Conceptual approach for investigating the provision and use of ISS in cross-border regions.

The first column of presents the different ISSs identified in the literature. According to various studies (Kilelu, Klerkx, and Leeuwis Citation2014; Klerkx and Leeuwis Citation2008; Proietti and Cristiano Citation2023), ISSs can be provided in the form of subject matter expertise (e.g. by agronomists) but can also focus on matching information and resource supply with the demand (e.g. making sure the farmer finds the right agronomist), also referred to as ‘intermediation’ (Koutsouris Citation2014). ISSs can be distinguished by different functions: knowledge brokering, network building, institutional support, innovation process monitoring, capacity building, demand articulation, and access to resourcesFootnote2 (Kilelu et al. Citation2011; Faure et al. Citation2019; Mathé et al. Citation2016). ISSs can be funded privately or publicly, and provided by private advisors, public extension agents, companies, or researchers (Kilelu, Klerkx, and Leeuwis Citation2014; Birner et al. Citation2009; Christoplos Citation2010; Klerkx and Leeuwis Citation2008; Parkinson Citation2009; Swanson and Rajalahti Citation2010; Proietti and Cristiano Citation2023). We argue that ISSs in a cross-border setting are similar to a national advisory system. Hence, the services focus on support for knowledge exchange and research as well as for the development of business strategies, opportunities for networking and advanced training, and advice on legal structures (including patents), market structures and financing (Kilelu et al. Citation2011; Galanakis Citation2006; Lundquist and Trippl Citation2013).

The second column presents the aspects defining the level of cross-border regional integration. Weakly integrated cross-border regions are characterized by major differences in science and knowledge infrastructure, economic structure, policy structure, institutional set-up, the nature of the linkages and accessibility (Lundquist and Trippl Citation2013). In strongly integrated regions, these aspects are more homogeneous. It is worth mentioning that neither too much nor too little integration is favorable for innovation because different systems can also offer chances for mutual learning and can be beneficial for innovation development (Boschma Citation2005; Balland, Boschma, and Frenken Citation2015; Knickel et al. Citation2021). We argue that the provision and use of ISSs in cross-border regions depends on the aspects defining cross-border regional integration, which will be described in detail further below.

The third column presents the factors that influence the provision and use of the ISSs. The list is based on the findings from previous research and some factors are designed for or have evolved from a national context. We also included research results which were not exclusively focusing on two neighboring countries because Kurowska-Pysz (Citation2016) shows that most enterprises treat foreign markets in the same way, be they just across the border or further away. In the remainder of the section, we relate the cross-border aspects to the ISS to illustrate the factors that influence ISSs.

The aspect ‘Nature of linkages’ defines the kind of established relationships which can be mutual or one-sided, driven by opportunities for knowledge exchange or financial reasons and, hence, can influence the level of cross-border regional integration (Lundquist and Trippl Citation2013; Trippl Citation2010; Hekkert et al. Citation2007). Generally, there are fewer business relationships and networks with stakeholders from the bordering country (Tödtling and Kaufmann Citation2002). Jørgensen (Citation2014) proposes that SMEs lack motivation for cross-border interaction, but Makkonen and Leick (Citation2020) could not confirm this finding. We suggest that the provision and use of the ISSs are affected by different opportunities to establish networks in the cross-border setting (Tödtling and Kaufmann Citation2002; Dashti and Schwartz Citation2018).

The aspect ‘Accessibility’ focuses on infrastructural barriers for cross-border regional integration (Klein Woolthuis, Lankhuizen, and Gilsing Citation2005; Lundquist and Trippl Citation2013). Such physical barriers can influence how and with whom enterprises cooperate. SMEs are confronted with increased costs for coordinating networks in cross-border settings (D’Ambrosio et al. Citation2017), although involving stakeholders from across the border could help enterprises in boosting their innovation activities (Dashti and Schwartz Citation2018). We expect that increased coordination costs influence primarily the use of ISSs across the border (D’Ambrosio et al. Citation2017).

The aspect ‘Socio-cultural proximity’ acknowledges that socio-cultural differences influence the level of cross-border regional integration (Hermans, Klerkx, and Roep Citation2015; Klatt and Herrmann Citation2011). It is well known that AKIS must be tailored to the national, and even regional setting, and therefore cannot be simply transferred from the setting of one country to another (Pfotenhauer and Jasanoff Citation2017; Klerkx et al. Citation2017b). A common language is an important starting point for cross-border cooperation (Borges et al. Citation2022; Capello, Caragliu, and Fratesi Citation2018). Doezema et al. (Citation2019) questions whether broad categories across diverse national contexts are suitable as explanatory factors to derive limitations and opportunities for any system because they found similarities in countries which do not seem obvious in the first place. We suggest that an important factor for the provision and use of ISSs is openness and willingness to engage in cross-border cooperation (van den Broek, Benneworth, and Rutten Citation2019; Klatt and Herrmann Citation2011; Capello, Caragliu, and Fratesi Citation2018) and the ability to overcome language differences (Capello, Caragliu, and Fratesi Citation2018; Klatt and Herrmann Citation2011; Balogh and Pete Citation2017).

The aspect ‘Science & knowledge base infrastructure’ considers the presence of education and research facilities important for cross-border regional integration (Lundquist and Trippl Citation2013; Trippl Citation2010), which are also an essential element of AKIS. Universities, for instance, can equip people with the necessary skills and knowledge to innovate (see also Vos Citation2005; Vos, Keizer, and Halman Citation1998) and often act as bridge builders for enterprise interaction in cross-border regional networks (van den Broek, Benneworth, and Rutten Citation2019). Hence, we presume that different opportunities to cooperate with universities and varying access to (project) funding influence how easily SMEs can benefit from knowledge exchange and research, e.g. attracting interest in qualified staff, participating in research projects and accessing funding across the border (van den Broek, Benneworth, and Rutten Citation2019; D’Ambrosio et al. Citation2017; Fidrmuc and Hainz Citation2013).

The aspect ‘Institutional set-up’ of a cross-border region is defined by the set of laws, regulations and future regional development plans which determine the integration of a cross-border region (Lundquist and Trippl Citation2013; Trippl Citation2010). Klerkx et al. (Citation2017b) found that different countries’ institutions create country-specific path-dependencies in an AKIS resulting in different starting positions for co-innovation. They also concluded that country-specific adjustments of institutional conditions are required for effective ISS provision and use. However, municipalities experienced difficulties to influence policy making beyond the border (van den Broek and Smulders Citation2015). Here, cross-border brokers can assist in bridging institutional and socio-cultural gaps and facilitating cross-border collaboration (Klerkx and Guimón Citation2017; Ma, Kaldenbach, and Katzy Citation2014). Cross-border brokers can take on different responsibilities (Walther and Reitel Citation2013) and help by fulfilling three critical roles: ‘conveners’ connect partners with relevant actors, facilitate public-private partnerships, and bridge social capital; ‘mediators’ facilitate the development of structural, relational, and cognitive dimension of bonding ties between partners; and ‘learning catalysts’ facilitate passive, active, and interactive learning processes among partner organizations (Stadtler and Probst Citation2012). We imply that ISS provision and use in a cross-border setting is influenced by legal differences, different institutional set-ups, and availability of cross-border brokers (Klerkx and Guimón Citation2017; Klerkx et al. Citation2017b; van den Broek and Smulders Citation2015; Walther and Reitel Citation2013). Here, cross-border brokers can thus act as a ‘broker between brokers’, as ISSs also fulfill brokering roles as noted in the introduction.

The aspect ‘Economic structure’ represents the influence of market structures and strategies on industry development for cross-border regional integration (Lundquist and Trippl Citation2013; Trippl Citation2010; Hermans, Klerkx, and Roep Citation2015). A cross-border context affects the extent to which SMEs have to adapt their business strategies in cross-border regions compared to national contexts (Milani Citation2020). They have to, for example, consider the presence of regional competences in terms of qualified labor forces in the region and account for differences in supply chain structures (Trippl Citation2010) and potentially compensate for border effects (Capello, Caragliu, and Fratesi Citation2018). We derive that the provision and use of ISS is influenced by SMEs’ ability to adapt their business strategy when operating across the border.

The aspect ‘Policy structure’ refers to the political system and governance structures which define the level of cross-border regional integration (Hermans, Klerkx, and Roep Citation2015; Lundquist and Trippl Citation2013; Trippl Citation2010). Prior research shows that cross-border policy network organizations do not have the required power to establish transnational governance structures but that they can mainly mobilize actors in the regions to foster change (Miörner et al. Citation2018; Walther and Reitel Citation2013). The European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) aims to facilitate cross-border regional integration with its Interreg program. Interreg joint-secretariates are responsible for implementing the program which is accessible for actors of the whole cross-border region and offers several ISSs, such as funding, networking opportunities, and introduction of the cross-border market structure. However, the impact of the Interreg program for enterprises is not always obvious (Kurowska-Pysz Citation2016). We suggest that the long-term planning of cross-border regional development influences ISS provision and use in cross-border (Szmigiel-Rawska Citation2016; Walther and Reitel Citation2013).

The list of mentioned factors is certainly not exhaustive because every cross-border region is unique. However, these factors allow to capture the dual embeddedness (see e.g. Klerkx and Guimón Citation2017) of ISSs in cross-border regions. The list of factors can further be extended based on the results of this research.

Methods

Region

We conducted a case study in the Dutch-German cross-border region Euregio Rhine-Waal. A case study serves to uncover aspects specific to a particular type of objects, in this case, cross-border regions. The method allows to learn from even a single case and in that sense it should be ‘characteristic’ rather than ‘representative' (Yin Citation2009). Through analytical generalizations from the specific case of one cross-border region, we uncover the specific processes and mechanisms in place in this (and potentially other) cross-broder regions compared to single-country contexts. The region covers the German areas of Kleve, Wesel, Duisburg, and Dusseldorf and the Dutch areas of Achterhoek, Gelderland, the northeast of Noord-Brabant, and Noord-Limburg. It is a predominantly rural cross-border region with urban centers close by. The agri-food sector is economically important in this region featuring intensive animal husbandry, horticulture, and food processing industry (LWK NRW Citation2021). Intensive agricultural production has led to environmental problems (i.e. high ammonia concentrations in groundwater and surface waters), which have created an urgent need for improved production techniques in the agri-food sector, i.e. agricultural innovation (LWK NRW Citation2021; Smit et al. Citation2015). This need for innovation also offers business opportunities for SMEs in the Euregio Rhine-Waal.

Currently, the Euregio Rhine-Waal is among the most innovative regions in Europe (European Commission Citation2019b) and therefore particularly well suited to study cross-border ISS. The history of intrinsically motivated cross-border interaction in the region officially dates to 1963, i.e. people in the region drove this development. In 1993, the first cross-border public-law special administrative unit in Europe (in German ‘grenzüberschreitende, öffentlich-rechtliche Zweckverband in Europa’) was founded in this region. Since then, this administrative unit aims to improve and intensify economic and social cross-border cooperation in the Dutch-German border region (Euregio Rhine-Waal Citation2022). After the foundation of the EU, an Interreg joint-secretariat was established in the Euregio Rhine-Waal – similar to many other European border regions - to promote cooperation and facilitate the economic development of the region. Between 2008 and 2020, 177 projects were supported there within the scope of InterregFootnote3 (Gemeinsames INTERREG-Sekretariat Citation2021). Unlike in the Euregio Rhine-Waal, the formation of many newly established administrative bodies was extrinsically motivated and there was less to no prior commitment and continuous growth of cross-border cooperation in the ‘new’ cross-border regions (Perkmann Citation2003). Thus, the (positive and negative) experiences of the Euregio Rhine-Waal offer valuable insights for other areas with a less rich history and the lessons learned from this case study are also useful for other cross-border regions.

Content analysis of websites providing ISSs

First, we conducted a content analysis of websites to become familiar with the ISS provided in the region. This first phase of the research helped to design the interview questions. We identified the websites for the content analysis through a Google search with prior defined search strings (Appendix, Table A1). After excluding doubles, newspaper articles, and outdated programs, we arrived at the sample of 14 Dutch and 20 German websites providing ISSs. The websites were analyzed through a pre-defined coding tree focusing on the ISSs listed in the conceptual framework (Kilelu et al. Citation2011; Faure et al. Citation2019).

Interviews with providers and users of ISSs

In the second phase of this study, we conducted 19 semi-structured interviewsFootnote4 with stakeholders in the Euregio Rhine-Waal: 10 interviewees were located on the Dutch side of the border and nine in the German oneFootnote5 (Appendix, Table A2). Interviewees were recruited from the website search of ISS providers and the personal network based on their location in the Dutch-German cross-border region and experience with providing or using ISS. We contacted potential interviewees from academia, local/regional governmental institutions, and innovation brokers via email and phone but some explained that they were unavailable for an interview due to time constrains or did not respond at all. The list of interviewees was extended through snowballing technique, i.e. asking interviewees to suggest other interview partners – this procedure was especially valuable for recruiting interviewees among SMEs. We elaborated case study protocols prior to starting the research and followed them throughout the research process. We interviewed stakeholders of equivalent institutions in the German and the Dutch regions: We asked four stakeholders from academic institutions and nine local and regional experts (including government institutions) about their role in supporting innovation and experiences with the provision and use of ISSs across the border. Additionally, six agri-food entrepreneurs were asked about their experience with available ISSs and how they could be improved. At that point of information saturation, we stopped actively recruiting further participants for interviews beyond our initial list. Two researchers conducted the interviews in English or German – depending on the interviewees’ preferences. We collected informed consent, and recorded and transcribed all interviews. The main points were shortly reflected between the two researchers after finishing each interview. However, the actual coding of the transcripts took place once all interviews were conducted. We followed Stebbins (Citation2001) approach for exploratory research techniques and combined deductive and inductive codingFootnote6 to explore how ISSs are provided and used and to identify the related limitations and opportunities in the cross-border region.

Results

In this section, we show how ISSs are provided and used in the cross-border region Euregio Rhine-Waal and how stakeholders perceive limitations and opportunities of ISS provision and use. We first provide an overview of the websites results and present ISS operating in the Euregio Rhine-Waal, followed by the inputs from the interviews.

ISSs operating in the Euregio Rhine-Waal

14 Dutch and 20 German websitesFootnote7 offered all seven ISSs identified in the literature, namely Opportunities for networking, Support for knowledge exchange and research, Support with developing business strategies, Offer of advanced training, Advice on financing, Advice on legal structures (including patents), and Advice on market structures. Often one website provided information about multiple ISSs and the frequency of ISSs offered was similar on both sides of the border, with advice on financing, opportunities for networking and support with developing business strategies as the top 3 ().

Table 2. Number of websites offering specific ISSs.

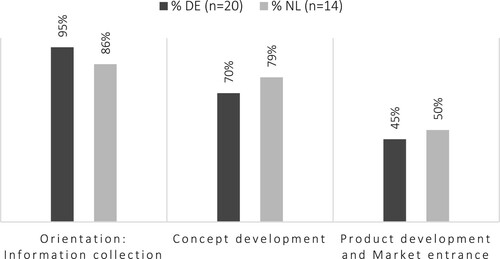

Among the German websites, only three ISSs providers (15%) specifically addressed the agri-food sector while the others were offered independent of the sector. Among Dutch websites, quite the contrary was the case: 10 ISS providers (71%) specifically addressed the agri-food sector. ISSs on German websites targeted more often explicitly SMEs and start-ups (55%; 80%), compared to ISSs on Dutch websites (21%; 29%). ISSs on German and Dutch websites offered to a similar extent support at different stages of the innovation process: (1) Orientation: information collection, (2) Concept development and (3) Product development and Market entrance (see ).

We found that only the Euregio Rhine-Waal with its Interreg program explicitly offered ISSs tailored to enterprises on both sides of the border. All other ISS providers appeared to target only national enterprises. An indication of the national focus was that the websites’ information was mainly provided in the country's native language and rarely in the language of the neighboring country or English (German websites: 4/20 in Dutch, Dutch websites: 0/14 in German; German websites: 7/20 in English, Dutch websites: 9/14 in English).

The outcomes of the website analysis were also used to develop information material for SMEs in the region (available in German: Neuberger and Darr Citation2021).

Perceived limitations and opportunities of ISS provision and use

We have anonymized the interview respondents and refer to them in brackets as R1, R3, etc. whenever specific cases are concerned. The interview results are structured according to the provision or use of ISSs and divided into limitations and opportunities. An overview of the perceived limitations and opportunities of ISSs is presented in the discussion section together with the practical implications ().

Table 3. Overview of perceived limitations and opportunities of ISSs in the Dutch-German cross-border region & its practical implications.

Provision of ISSs in a cross-border setting: limitations and opportunities

One of the limitations of ISS provision concerns the different priorities of countries and regions, for instance, national governments tend to focus on national interests and support national enterprises (R3, R15). Hence, different national interests of bordering countries are in competition, which complicates the agreement on a cross-border focus (R15). As a result, ISSs mainly target the national context, for example, tax benefits for start-ups and SMEs on the Dutch side (R7). Another example of different national priorities is the relative importance of the agricultural sector in Germany versus the Netherlands. While innovation hubs such as Food Valley and Greenports were founded in the Netherlands, something comparable is still missing in Germany.

Different institutional structures is another limitation that influences several aspects of the ISS provision side. Respondents mentioned that different legal systems (R3, R15), public authorities and connections to academic institutions influenced the appropriate supply of ISSs. In the Dutch and German region, several institutions support SMEs with advanced training and developing business strategies. Over time, these institutions reorganize and change within the country, which might in turn result in difficulties for SMEs to access ISSs. For example, while in Germany SMEs can currently contact the ‘Industrie- und Handelskammer’ (i.e. chamber of industry and commerce) for training and business strategy development, its Dutch counterpart, the ‘Kamer van Koophandel’ no longer covers this function (R17). Another limitation concerns different structures of academic institutions which directly affect opportunities for knowledge exchange and research. For example, a greater division was observed between the three stakeholder groups: academic institutions, businesses, and local/regional government institutions in the German part of the cross-border region (R2). Some respondents believed this has led to academic research being detached from the market (R4). In contrast, in the Netherlands, the different stakeholder groups seemed to be more closely connected to research (R2), forming an innovation ecosystem (R3). Because of these differences, our sample of entrepreneurs in the German part approached universities only if they are ‘stuck’ with a certain issue (R1) or have no resources available to develop a solution internally (R18). At the same time in the Dutch part, the agri-food enterprises are used to continuous cooperation with universities and renting of premises (R10) or equipment (R8) from them. These different structures limit ISS related to cross-border knowledge exchange because universities engage with enterprises in different ways.

An opportunity to access ISSs in the whole cross-border region is the presence of established cross-border structures which can be promoted and extended by the ISS provider. Respondents suggested drawing SMEs’ attention to already available matchmaking organizations such as the Euregio office (R11), the cross-border business club (R2), or specialized innovation spaces, such as the Dutch incubator Food Valley (R2, R8, R10). The Interreg program also represents an established structure which provides not only funding to cross-border projects but also contacts (R6, R7, R10, R11). SMEs from both regions value the Interreg program because of low entry requirements, support from local administrations, and reasonable chances to receive funding (R8, R11, R18). Moreover, an already available two-step evaluation tool helps businesses to access the market across the border (the ‘business evaluation tool’ can be access at: https://internationalisierungsscan.eu/). The tool was developed by the Fontys University of Applied Sciences, which first evaluates how much the firm already focuses on a bordering country, and second, helps SMEs to develop a targeted business strategy. This business strategy often includes matchmaking to compensate for missing market knowledge (R2). Another opportunity is a planned cooperation between a Dutch and a German bank, which should stimulate cross-border investment and access to financing (R2).

Use of ISSs in a cross-border setting: limitations and opportunities

A general limitation for SMEs is the lack of time and resources to search for and request the appropriate ISS which embody certain ISSs. SMEs are often not aware of ISSs such as networking opportunities and possibilities for knowledge exchange and research on the other side of the border (R10), and do not know ISS providers (R3). From the SMEs’ (user) viewpoint, setting priorities of time and resources is required in their daily business, which includes deciding which ISS services are most efficient for them. However, they rarely have the resources to remain up-to-date on public funding options and face difficulties in selecting the most suitable and promising option (R2, R5).

An entrepreneur expressed that their team was not aware of existing assistance (i.e. brokers) to select among ISSs (R18). There are brokering organizations (e.g. Oost NL, the Euregio office) assisting enterprises in the process of finding potential (cross-border) partners, but enterprises still need to articulate their needs and expectations (i.e. clear goals), something that is perceived as difficult (R9). A local/regional expert indicated that different mentalities could be a reason why individual enterprises seldom look for collaborators abroad (R17). However, one of the interviewed entrepreneurs shared that they are open for cross-border cooperation but need access to innovation brokers to connect with suitable partners because they lack a good network (R14). In a cross-border setting, casual unplanned interaction between actors rarely happens and the process does not seem to be sufficiently facilitated (R13).

Uncertainty is another limitation that primarily SMEs experience when using ISSs such as financing and networking opportunities. As already mentioned, enterprises’ time constraints result in careful consideration of payoffs for every decision. This includes deciding in favor of certain funding applications and networking events over other ones. In a cross-border setting, the level of uncertainty increases due to the unfamiliarity with the neighboring country, both in terms of administrative effort and cooperation outcome.

The interaction between SMEs and ISS providers often requires an administrative effort, which might not always be seen as reasonable by SMEs. The administrative effort to receive financing might include writing a proposal, a business plan, and sometimes interim reports. Within a country, relevant offices can assist SMEs by offering advice on knowledge exchange, financing, and business development, but cross-border cooperation between such organizations is limited. One reason could be the lack of clearly defined goals within a country and a different division of tasks across the border (R2) - an exception mentioned by many respondents is the Interreg program.Footnote8

The Interreg joint-secretariate Deutschland-Nederland is the only provider of ISSs specifically dedicated to facilitating interactions in a cross-border setting that offers a range of particularly broker services including funding, networking opportunities, introduction to market structure, and business strategy development through the Interreg program. Relevant offices support Interreg program funding applications and assist in further project coordination. This appeared to function equally effectively on both sides of the border. The interviewed SMEs perceived the Interreg grant application itself as less demanding than other EU or regional and national government funding schemes. However, the administrative tasks to be performed throughout the project appeared to SMEs to be more stringent and elaborate in Interreg (R8). Another interesting finding was that while Interreg was initially planned to be only for enterprises, high administrative costs led to the involvement of universities to take over the coordination function, as illustrated by the following quote of a university representative:

It is simply not possible to find five Dutch companies to work with five German companies unless a university or other research institution takes over the coordination (R7, German University).

Another limitation for the use of ISSs was related to uncertain cooperation outcome. A local/regional expert highlighted that the ISS availability of networking opportunities was very important but can only work if entrepreneurs have an immediate benefit from it (R17). This stakeholder also observed that enterprises preferred to attend network events in their own country. However, there is one exception: if an SME is already familiar with the organizers of an event and trust relationships are already established, SMEs already feel connected and hence more willing to receive networking support and attend an event across the border (R17). Consequently, language and culture embody some sort of uncertainty in connection with anticipated cooperation outcomes. If unfamiliar with both, the outcomes are even more difficult to estimate (R2, R11, R19). Another example from the participation in an Interreg project: financing is often not the main reason to participate but seen as a chance to establish contacts (R17). However, during an Interreg project, SMEs often succeed only in initializing partnerships which will still need to evolve over time (R2). Occasionally, networks cannot be sustained and as soon as funding ends, so does networking. Thus, enterprises cannot fully benefit from such projects as initially expected (R9). Hence, the ISS networking opportunities must be designed in a sustainable manner, e.g. by focusing on a specific aim or topic (R6, R16).

An opportunity for increasing attention to and use of ISSs across the border is the promotion of experiences within the cross-border region. A stakeholder observed that (positive) experiences about cooperation and doing business across the border could change predefined opinions (R19). In our study, the demand for competences and expert knowledge appeared more important than the location (R17, R18), which indicates the value of ISSs that stimulate knowledge exchange and research. Becoming familiar with the working patterns and the culture of neighboring partners can increase enterprises’ willingness and openness to use ISSs across the border. One of the interviewed stakeholders highlighted that actual willingness to collaborate was helpful in overcoming cultural differences because these differences can also exist within one country, i.e. southern, and northern parts of Germany (R3). Respondents also reported that a native speaker was not necessarily required to operate cross-border but a person familiar with the business culture of the neighboring country is recommended (R2). In Interreg, different cultures, communication patterns, and mentalities to handle projects and deliverables collide and this experience can help enterprises to develop an understanding and to align working patterns to some extent (R15). If connections within a project were initiated successfully and SMEs experienced benefits, cross-border cooperation can outlive the duration of a project (R9). This observation indicated that the development of trust was important for cooperation and partnerships in the long term. As one of the respondents noted, established structures end at the border, only the reduction of these administrative borders might help to decrease borders in individuals’ mind-sets (R17). Stakeholders also acknowledged that Interreg projects represented a low threshold and high success rate for SMEs to ‘get in touch with a new country, a new way of working, new culture’ (R2). Consequently, such new experiences might increase SMEs’ cultural awareness and therefore promote further attempts to access ISSs across the border in the future.

Discussion

In this research, we investigated how ISSs are provided and used in the cross-border region Euregio Rhine-Waal and we explored how stakeholders perceive limitations and opportunities of these services. The results indicated a difference in the factors influencing the provision compared to the use of ISSs in the cross-border region. One of the key findings is that the level of cross-border regional integration in the provision of ISSs is primarily influenced by different institutional set-ups and the availability of brokers, while the use of ISSs is mainly affected by coordination costs (accessibility) and cultural awareness (socio-cultural proximity). Furthermore, it appears that no structured mechanisms to match the provision with the demand of ISS seems to be implemented. Here, we will reflect on these findings against the literature on the topic of internationalization of ISSs and elaborate on practical implications for the case study region Euregio Rhine-Waal and other cross-border regions (see also ).

Cross-border settings and the provision of ISSs

Based on our results, the biggest limitation for the provision of ISSs in our case study region was the focus on national interests resulting in different national priorities and institutional structures. On the positive side, brokers can help to promote available ISSs and connect SMEs with well-established ISS structures across borders. We will now discuss this in more detail.

Different institutional structures

Structural differences can complicate the establishment of a common cross-border ISS system (and particular associated cross-border micro-AKIS) because different starting conditions in either country are present (Klerkx et al. Citation2017b) and different interests must be balanced (Klerkx and Guimón Citation2017). Regardless of the long history of fostering cooperation in the Euregio Rhine-Waal, the institutional settings appear to differ within the cross-border region and ISSs primarily serve national interests and target almost exclusively national enterprises because governments prioritize the needs of their country. The content analysis of the websites also revealed a focus on national objectives because information was primarily presented in the national language. Our findings are in line with various prior studies (Klerkx and Guimón Citation2017; Klerkx et al. Citation2017b; van den Broek and Smulders Citation2015). First of all, the differences of the legal system, the institutional set-up, and the knowledge infrastructure limit the integration process of national ISSs in a cross-border setting (Klerkx et al. Citation2017b; Lundquist and Trippl Citation2013). Secondly, transferring ISSs from one country to another is not possible without adjustments and the provision and use of ISSs is closely linked to the national context because of a lack of integration. These results resonate with findings elsewhere (Klerkx and Guimón Citation2017; Berdegué Sacristán Citation2001; Klerkx et al. Citation2017b; Proietti and Cristiano Citation2023; Fieldsend et al. Citation2022). Third, our study confirms previous work (Klatt and Herrmann Citation2011) and shows that 10 years later and despite deliberate efforts to foster integration, cooperation remains difficult and may take even longer due to still lacking decisive influence on the development of sustainable cooperation activities (at governance levels). Our study provides a reality check in this sense for suggestions to create a level playing field for innovation in terms of institutional context and knowledge infrastructure (see e.g. Fieldsend et al. Citation2022; Klerkx et al. Citation2017b; Klerkx and Guimón Citation2017).

Cross-border brokers as part of established collaborative structures

The Interreg joint-secretariat Deutschland-Nederland was found to be the only provider of ISSs accessible on both sides of the border and, hence, links up two ISS systems existing in parallel in the two countries acting as a cross-border broker. Our results confirm prior research on the importance of international cross-border brokers to facilitate the provision of ISSs across the border for interested enterprises (Stadtler and Probst Citation2012; Ma, Kaldenbach, and Katzy Citation2014; Walther and Reitel Citation2013; Klerkx and Guimón Citation2017). While the AKIS literature speaks a lot about brokers and brokering, these are generally working within national AKIS, and the role of cross-border brokers is hardly mentioned and acknowledged (though probably well represented in practice), and this role could receive more attention in future AKIS studies and policies such as European Innovation Partnerships and multi-actor groups. In our Dutch-German case study region, some cross-border structures were already established and fulfill the three critical roles proposed by Stadtler and Probst (Citation2012): (1) The cross-border organization Euregio Rhine-Waal can answer general questions on the cross-border setting, connect partners with important actors and play a prominent role in sustaining cross-border relationships because it is also involved in key decisions and future development plans for the whole region (i.e. ‘convener’). (2) The Interreg joint-secretariat Deutschland-Nederland is responsible for implementing the Interreg program. Through implementing Interreg projects, structural, relational, and cognitive bonding ties between partners are facilitated (i.e. ‘mediator’). (3) Various Interreg project coordinators can facilitate learning processes among partner organizations on an intellectual and cultural level (i.e. ‘learning catalyst’).

Surprisingly, universities hardly took over the role of learning catalysts or developing cross-border connections in our case study region. This observation is contrary to prior research observations where universities contribute to cross-border connections and can even educate people toward a more cross-border mind-set (van den Broek, Benneworth, and Rutten Citation2019) or are interlinked in international knowledge hubs (Coenen, Moodysson, and Asheim Citation2004). We found that the interaction of SMEs with universities differed in the cross-border region. It tended to be more problem-driven in the German region and more co-development-oriented in the Dutch region. Typical of both regions was that enterprises were generally restricted in networking for knowledge exchange and research across the border. However, we also observed that universities to some extent facilitate cross-border accessibility of other ISSs due to universities’ predominant role as coordinators in Interreg projects. This observation hereby confirms the findings of Tagliazucchi et al. (Citation2021) but also highlights that the role of universities can and should be further exploited in international collaboration including cross-border regions.

Cross-border settings and the use of ISS

The biggest limitation for the use of ISSs in our case study region was caused by SMEs often lacking resources to familiarize themselves with available ISS options and perceived high uncertainty about the pay-offs of using ISSs across the border. Disseminating experiences of SMEs can offer an opportunity to motivate further SMEs to extend their business operations across the border.

Coordination costs (accessibility)

The results showed that potential benefits of cross-border integration were not immediately apparent at the enterprise level because learning was costly for SMEs: searching for and accessing relevant information, training and education come at a cost, also in national innovation systems (Lundvall Citation2010). We found that enterprises tended to be uncertain in the initial phase of finding partners and establishing contacts in cross-border networking because of the required time and resource investments. Hence, SMEs put a similar effort when operating ‘just’ across the border or further away and we argue that it should be easier for them to cooperate across the border compared to other international partners. Enterprises usually operate within the national context and their expertise is less developed or completely absent for a neighboring country (similar to what Kurowska-Pysz (Citation2016) found in the Czech-Polish border region).

We also observed that lacking knowledge of how to do business and how to access ISSs across the border caused uncertainty for enterprises. An example of SMEs’ uncertainty reported in our study was that requesting financing might lead to dependence of the enterprise on this funding for their business thus causing undesired consequences in the long term. Within our study, cross-border accessibility of financing was limited to the Interreg funding and applied to the context of Interreg financing. Prior research (Szmigiel-Rawska Citation2016; Samara et al. Citation2020) shows that not only enterprises can become dependent on Interreg financing. One illustrative example in this respect are eastern European countries where cross-border organizations often did not evolve naturally after the EU accession. This in turn has led to continued dependence on funding for developing cross-border relations (Szmigiel-Rawska Citation2016; Shepherd and Ioannides Citation2020). Our findings confirm that costs occur because SMEs need assistance to deal with ISS providers (Christoplos Citation2010), demand articulation and partner identification (e.g. knowledge, finance) (Klerkx and Guimón Citation2017; Klerkx and Leeuwis Citation2008; Knickel et al. Citation2021). We derive that the aspect Accessibility, which originally accounts for physical barriers of cross-border regional integration, should also comprise coordination costs associated with (1) additional efforts of extension and advisory agents to manage brokering tasks and (2) SMEs adjusting their business strategy to cross-border requirements.

Innovation culture and cultural awareness (socio-cultural proximity)

We observed different cultures of innovation and views on co-innovation through different responsibilities of and task division between stakeholder groups in the bordering countries. However, enterprises demonstrated willingness and motivation to establish new contacts and partnerships while at the same time expressing their limited awareness of available networking opportunities across the border. While prior research clearly showed the importance of socio-cultural barriers for cross-border cooperation (Capello, Caragliu, and Fratesi Citation2018; Balogh and Pete Citation2017), research demonstrated opposing results with regard to enterprises motivation for border interaction (Jørgensen Citation2014; Makkonen and Leick Citation2020). At the same time, Pfotenhauer and Jasanoff (Citation2017) show that countries’ culture influences the articulation of expectations on what innovation is (‘imaginaries of innovation’) and corresponding development of a common innovation strategy. This implies that the rights and the responsibilities of all stakeholders in innovation processes should be clearly communicated in cross-border innovation projects.

Moreover, following Klerkx and Guimón Citation2017, a strategy is needed to address deficiencies of the regions to develop a common understanding of the goals and agree on a common innovation strategy. In line with Klerkx (Citation2020), and also highlighted by Fieldsend et al. (Citation2022), the aspect of cross-border collaboration and the difference in ‘innovation cultures’ across EU member states could receive much more attention.

Practical implications for the case study region Euregio Rhine-Waal and other cross-border regions

This study can be useful not only for the Euregio Rhine-Waal but also other regions can benefit from the suggestions mentioned thereafter. We highlight four practical implications. Starting from the identified limitations, we discuss strategies to reduce these and decrease according weaknesses of the region, one for provider and one for the users side:

In practice, the findings of our study suggest that ISSs should be designed, extended or adopted following a co-creation approach (Lioutas et al. Citation2019; Proietti and Cristiano Citation2023) and managed flexibly (Ingram et al. Citation2020). Frequent communication between enterprises, regional and national entities, and cross-border organizations responsible for regional development is essential to improve ISS provision because these affected stakeholders know best what different institutional structures are blocking. In this research, we could not observe any attempts to match the provision of ISS with the needs of those using them as suggested in Kilelu, Klerkx, and Leeuwis (Citation2014). It can be assumed that such learning processes also take place within national borders.

Following a co-creative approach for ISSs provisioning can facilitate common learning from each other, help stakeholder gaining first-hand experience of cross-border cooperation and finally encourage adjusting ISSs offered. The framework used in this study can be applied to other cross-border regions to identify provided ISS. The results of this study can serve as the base for discussion specifically in the Euregio Rhine-Waal, where the Euregio office supported by local municipalities can initiate such a co-creation approach to (re-)design ISSs. The outcomes of such co-creative approaches ultimately depend on the openness and willingness of providers and users to cooperate (van den Broek, Benneworth, and Rutten Citation2019; Klatt and Herrmann Citation2011; Capello, Caragliu, and Fratesi Citation2018) and in the best case lead to such an inclusive approach observed in Proietti and Cristiano (Citation2023).

A first step toward reducing coordination costs for using ISS was already initiated: the business evaluation tool developed by the Fontys University of Applied Sciences follows a survey approach to identify the readiness of a business to operate across the border and could help SMEs to identify weaknesses and equip them with the necessary skills and knowledge (see also Vos Citation2005; Vos, Keizer, and Halman Citation1998). To assist the users of ISS, more targeted promotion of available ISS is necessary to ease the information finding, a tool like the business evaluation could help SMEs in scanning through available offers. Local universities can develop such a tool in cooperation with local municipalities, and ISS providers. However, uncertainties cannot be completely eliminated. Ma, Kaldenbach, and Katzy (Citation2014) recommend small projects to become acquainted with the structures across the border and conducting a feasibility study before entering a market across the border.

We identified two opportunities which can be used to advance the strengths of the region, one for the provider and one for the user side:

Similar to Miörner et al. (Citation2018), we consider it advisable to build on structures which are present in cross-border regions and to broaden the national focus to transnational to arrive at a common cross-border strategy. In our case, brokers, such as the Euregio office, Interreg secretariate or others (e.g. Oost NL), can help in the translation of actions, goals and expected outcomes of offered ISSs in a cross-border setting. Additionally, the Euregio Rhine-Waal but also other cross-border organizations could, for instance, facilitate cross-border integration by initiating an Interreg program that is even more tailored to the needs in the region and less driven by general regional development goals.

Furthermore, we suggest that sharing experiences with available expert knowledge and cultural awareness can promote the use of ISS by other enterprises. Euregio offices/cross-border organizations should provide room for exchanging ideas for demand and supply in both countries and raising awareness of different ideas and goals and to encourage users of ISS to share their experiences. Possible channels can be newspapers, social media and presentations in industry associations and business clubs. ISS providers can also install feedback mechanisms to learn and adjust their offered ISS and gain insights into the innovation culture of SMEs.

Limitations of this research

Due to the explorative character of our study, our findings must be interpreted with caution. We focus on the Dutch-German cross-border region Rhine-Waal and certain limitations and opportunities discussed in this study might pertain to other European cross-border regions with similar contexts, while others might not apply to the regions with a more recent history of cooperation. First, whereas our case study region has already showed a long history of cross-border cooperation, cross-border regions with a more recent history of cooperation might face even more hurdles. Second, the agri-food sector is similarly important in the Dutch and German regions of the Euregio Rhine-Waal and cross-border regions with different industrial foci on either side of the border might face other cross-border factors influencing innovation.

The respondents were recruited based on their insights and experiences with ISSs in the cross-border region, but it was especially difficult to engage enterprises in sharing their experiences. However, risk, uncertainty, and a lack of resources are common challenges in innovation development. Future research is necessary to (1) measure the effectivity of ISS, (2) characterize how ISS providers operate in socio-cultural and institutional environments, and (3) explore cross-border related factors influencing the provision and use of ISSs in other cross-border regions, particularly in regions without a long history and tradition of cross-border cooperation.

Conclusion

Users of ISS could benefit from a cross-border ISS system due to a larger diversity of services accessible to them. ISS providers could expand their market and specialize more for the target groups in the cross-border region. Our research investigated how ISSs are provided and used in a cross-border region and explored the related limitations and opportunities perceived by different stakeholders.

The results indicate that the provision and use of ISS are closely linked to the national context and that parallel systems exist in bordering countries. The provision of ISSs across the border was limited by differences in structures and national priorities in the cross-border region. Furthermore, stakeholders perceived the use of ISSs across the border as restricted by unfamiliarity with responsible authorities, the administrative effort required, and the uncertainty about pay-offs.

The provision and use of ISSs in cross-border regions can meet enterprises’ needs only to a certain extent due to adaptation problems. Our research adds to the literature on advisory systems by showing that ISS sub-systems in cross-border regions are bound to a national context and that cross-border linkages between national sub-systems are lacking. We argue that ISSs in cross-border regions should consider costs associated with the effort of working across the border and try to minimize them, without having the illusion that a level playing field can be created easily. Cross-border brokers can help, and while these may already be implicitly and sometimes also explicitly operating, they could receive a more prominent place in AKIS policies and programs.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank their interviewees who were willing to share their experiences and insights, two student assistants who helped with the data preparation, and their colleagues who were engaged in several discussions in the context of this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

S. Neuberger

S. Neuberger is a Scientist at the Center for Innovation Systems & Policy of AIT Austrian Institute of Technology GmbH (Austria). During her PhD at Wageningen University (The Netherlands), she focused on SMEs working in the agri-food sector in a cross-border regional innovation system. Her research interest evolved towards foresight looking approaches in the areas of digitalization and food system transformation.

M. Knickel

M. Knickel is a social scientist working in agri-food research with transdisciplinary approaches. In her research she is interested in strengthening science-society collaborations by focusing on mutual learning for actors' capacity-building, knowledge integration processes and epistemic justice. She has expertise in fostering knowledge co-production processes in science-society collaborations aiming at transformative outcomes in the areas of agri-food and sustainable rural development (e.g. in Living Labs).

L. Klerkx

L. Klerkx is Principal Scientist at the Department of Agricultural Economics at the University of Talca (Chile) and Full Professor of Agrifood Innovation and Transition at the Knowledge, Technology and Innovation Group of Wageningen University (The Netherlands).

H. Saatkamp

H. Saatkamp is Associate Professor in the Business Economics Groups at Wageningen University (The Netherlands). His research focuses on Economics of Livestock Production and Soil Health. He has particular interest and over 20 years of experience in German-Dutch cross-border agricultural policy, with emphasis on Livestock Production, Quality Assurance and Epizootic Disease Control.

D. Darr

D. Darr is Professor of Agribusiness at Rhine-Waal University of Applied Sciences, Kleve (Germany). His research interests include the socio-economic analysis of smallholder agriculture and related land use decision-making, and the analysis of innovation processes in the agri-food industry. In addition to his teaching and research activities, he provides consulting services to companies and organisations in the agrifood sector and other clients.

A. Oude Lansink

A. Oude Lansink is the head of the department of Business Economics of Wageningen University and an adjunct professor at the University of Florida and Universitas Padjadjaran in Bandung. His research interests evolve around four main themes, i.e. dynamic efficiency and productivity analysis, economics of plant health and invasive species, sustainable performance of food supply chains and agribusiness, investments and sustainable finance in the agribusiness.

Notes

1 The case study focuses just on one specific cross-border regions, in which the mechanisms typical for cross-border regions (compared to single-country contexts) can be revealed. This region was selected because it offers a long history, insights, and lessons for other cross-border regions to compare themselves with.

2 Knowledge brokering consists of dissemination and communication of knowledge and technology. Network building includes matchmaking and gate keeping. Institutional support comprises boundary work (linking science, policy, and practice) and facilitating institutional change (changes in rules/regulations, working on attitudes and practice). Innovation process monitoring involves mediating relationships, aligning agendas, building trust, and sharing complementary assets. Capacity building covers organizational development, training, and competence building. Demand articulation focuses on scanning and foresight diagnosis (Kilelu et al. Citation2011). Access to resources covers activities to ease and support the availability of resources (Faure et al. Citation2019).

3 The Interreg funding programs always focused on supporting SMEs and hence it can be considered an ISS.

4 The Social Sciences Ethics Committee of Wageningen University & Research approved the study (CoC Number 09215846).

5 Another study was carried out with the same stakeholders but with a different research focus: the role of innovation brokers and academic institutions in fostering hybridization in cross-border cooperation (Knickel et al. Citation2021).

6 Deductive coding was applied to identifying ISSs; inductive coding was used to explore the cross-border-related factors.

7 List of ISS providers identified through the website analysis is provided in the Appendix (Table A3).

8 At the time of this research (i.e. data collection and analysis) the Interreg VA program was operating.

References

- Abdirahman, Z.-Z., M. Cherni, and L. Sauvée. 2014. “Networked Innovation: A Concept for Knowledge-Based Agrifood Business.” Journal on Chain and Network Science 14 (2): 83–93. https://doi.org/10.3920/JCNS2014.x003.

- Balland, Pierre-Alexandre, Ron Boschma, and Koen Frenken. 2015. “Proximity and Innovation: From Statics to Dynamics.” Regional Studies 49 (6): 907–920. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2014.883598.

- Balogh, Péter, and Márton Pete. 2017. “Bridging the Gap: Cross-Border Integration in the Slovak–Hungarian Borderland Around Štúrovo–Esztergom.” Journal of Borderlands Studies 33 (4): 605–622. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2017.1294495.

- Berdegué Sacristán, Julio A. 2001. “Cooperating to Compete: Associative Peasant Business Firms in Chile.” Dissertation. Wageningen University and Reserach.

- Birner, Regina, Kristin Davis, John Pender, Ephraim Nkonya, Ponniah Anandajayasekeram, Javier Ekboir, Adiel Mbabu, et al. 2009. “From Best Practice to Best Fit: A Framework for Designing and Analyzing Pluralistic Agricultural Advisory Services Worldwide.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 15 (4): 341–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/13892240903309595.

- Borges, João A. R., Sabine Neuberger, Helmut Saatkamp, Alfons Oude Lansink, and Dietrich Darr. 2022. “Stakeholder Viewpoints on Facilitation of Cross-Border Cooperation.” European Planning Studies, 30(4): 627–642. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2021.1988061.

- Boschma, Ron. 2005. “Proximity and Innovation: A Critical Assessment.” Regional Studies 39 (1): 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/0034340052000320887.

- Brink, Tove. 2018. “Organising of Dynamic Proximities Enables Robustness, Innovation and Growth: The Longitudinal Case of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs) in Food Producing Firm Networks.” Industrial Marketing Management 75: 66–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2018.04.005.

- Camagni, Roberto, Roberta Capello, and Andrea Caragliu. 2019. “Measuring the Impact of Legal and Administrative International Barriers on Regional Growth.” Regional Science Policy & Practice 11 (2): 345–366. https://doi.org/10.1111/rsp3.12195.

- Capello, Roberta, Andrea Caragliu, and Ugo Fratesi. 2018. “Compensation Modes of Border Effects in Cross-Border Regions.” Journal of Regional Science 58 (4): 759–785. https://doi.org/10.1111/jors.12386.

- Christoplos, Ian. 2010. “Mobilizing the Potential of Rural and Agricultural Extension.” Accessed November 20, 2023, http://www.fao.org/3/i1444e/i1444e.pdf.

- Coenen, Lars, Jerker Moodysson, and Bjørn T. Asheim. 2004. “Nodes, Networks and Proximities: On the Knowledge Dynamics of the Medicon Valley Biotech Cluster.” European Planning Studies 12 (7): 1003–1018. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965431042000267876.

- D’Ambrosio, Anna, Roberto Gabriele, Francesco Schiavone, and Manuel Villasalero. 2017. “The Role of Openness in Explaining Innovation Performance in a Regional Context.” The Journal of Technology Transfer 42 (2): 389–408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-016-9501-8.

- Dashti, Yossi, and Dafna Schwartz. 2018. “Should Start-ups Embrace a Strategic Approach Toward Integrating Foreign Stakeholders Into Their Network?” Innovation 20 (2): 164–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/14479338.2017.1403853.

- Doezema, Tess, David Ludwig, Phil Macnaghten, Clare Shelley-Egan, and Ellen-Marie Forsberg. 2019. “Translation, Transduction, and Transformation: Expanding Practices of Responsibility Across Borders.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 6 (3): 323–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2019.1653155.

- European Commission. 2008. “EU Cohesion Policy 1988-2008: Investing in Europe’s Future.” Accessed November 20, 2023, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/panorama/mag26/mag26_en.pdf.

- European Commission. 2017. “Boosting Growth and Cohesion in EU Border Regions: Communication from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament.” Accessed November 20, 2023, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/communication/boosting_growth/com_boosting_borders.pdf

- European Commission. 2019a. “A European Green Deal.” Accessed November 20, 2023, https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en.

- European Commission. 2019b. “Regional Innovation Scoreboard 2019.” Accessed November 20, 2023, https://doi.org/10.2873/89165.

- Faure, Guy, Andrea Knierim, Alex Koutsouris, Hycenth T. Ndah, Sarah Audouin, Elena Zarokosta, Eelke Wielinga, et al. 2019. “How to Strengthen Innovation Support Services in Agriculture with Regard to Multi-Stakeholder Approaches.” Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 28 (1): 145–169. https://doi.org/10.3917/jie.028.0145.

- Fidrmuc, Jarko, and Christa Hainz. 2013. “The Effect of Banking Regulation on Cross-Border Lending.” Journal of Banking & Finance 37 (5): 1310–1322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2012.09.007.

- Fieldsend, Andrew F., Evelien Cronin, Eszter Varga, Szabolcs Biró, and Elke Rogge. 2021. “‘Sharing the Space’ in the Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation System: Multi-Actor Innovation Partnerships with Farmers and Foresters in Europe.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 27 (4): 423–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2021.1873156.

- Fieldsend, Andrew F., Eszter Varga, Szabolcs Biró, Susanne von Münchhausen, and Anna M. Häring. 2022. “Multi-actor Co-innovation Partnerships in Agriculture, Forestry and Related Sectors in Europe: Contrasting Approaches to Implementation.” Agricultural Systems 202: 103472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2022.103472.

- Galanakis, Kostas. 2006. “Innovation Process. Make Sense Using Systems Thinking.” Technovation 26 (11): 1222–1232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2005.07.002.

- Garforth, Chris, Brian Angell, John Archer, and Kate Green. 2003. “Fragmentation or Creative Diversity? Options in the Provision of Land Management Advisory Services.” Land Use Policy 20 (4): 323–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-8377(03)00035-8.

- Gemeinsames INTERREG-Sekretariat. 2021. “INTERREG Deutschland - Nederland.” Accessed November 20, 2023. https://www.deutschland-nederland.eu/.

- Hekkert, M. P., R. A. A. Suurs, S. O. Negro, S. Kuhlmann, and R. E. H. M. Smits. 2007. “Functions of Innovation Systems: A New Approach for Analysing Technological Change.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 74 (4): 413–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2006.03.002.

- Hermans, Frans, Laurens Klerkx, and Dirk Roep. 2015. “Structural Conditions for Collaboration and Learning in Innovation Networks: Using an Innovation System Performance Lens to Analyse Agricultural Knowledge Systems.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 21 (1): 35–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2014.991113.

- Ingram, Julie, Pete Gaskell, Jane Mills, and Janet Dwyer. 2020. “How do we Enact co-Innovation with Stakeholders in Agricultural Research Projects? Managing the Complex Interplay Between Contextual and Facilitation Processes.” Journal of Rural Studies 78: 65–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.06.003.

- Jørgensen, Eva J. 2014. “Internationalisation Patterns of Border Firms: Speed and Embeddedness Perspectives.” International Marketing Review 31 (4): 438–458. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-09-2012-0147.

- Kilelu, Catherine W., Laurens Klerkx, and Cees Leeuwis. 2014. “How Dynamics of Learning are Linked to Innovation Support Services: Insights from a Smallholder Commercialization Project in Kenya.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 20 (2): 213–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2013.823876.

- Kilelu, Catherine W., Laurens Klerkx, Cees Leeuwis, and Andy Hall. 2011. “Beyond Knowledge Brokering: An Exploratory Study on Innovation Intermediaries in an Evolving Smallholder Agricultural System in Kenya.” Knowledge Management for Development Journal 7 (1): 84–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/19474199.2011.593859.

- Klatt, Martin, and Hayo Herrmann. 2011. “Half Empty or Half Full? Over 30 Years of Regional Cross-Border Cooperation Within the EU: Experiences at the Dutch–German and Danish–German Border.” Journal of Borderlands Studies 26 (1): 65–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2011.590289.

- Klein Woolthuis, Rosalinde, Maureen Lankhuizen, and Victor Gilsing. 2005. “A System Failure Framework for Innovation Policy Design.” Technovation 25 (6): 609–619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2003.11.002.

- Klerkx, Laurens. 2020. “Advisory Services and Transformation, Plurality and Disruption of Agriculture and Food Systems: Towards a new Research Agenda for Agricultural Education and Extension Studies.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 26 (2): 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2020.1738046.

- Klerkx, Laurens, and José Guimón. 2017. “Attracting Foreign R&D Through International Centres of Excellence: Early Experiences from Chile.” Science and Public Policy 44 (6): 763–774. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scx011.

- Klerkx, Laurens, and Cees Leeuwis. 2008. “Matching Demand and Supply in the Agricultural Knowledge Infrastructure: Experiences with Innovation Intermediaries.” Food Policy 33 (3): 260–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2007.10.001.

- Klerkx, Laurens, Pieter Seuneke, Pieter de Wolf, and Walter A. Rossing. 2017b. “Replication and Translation of Co-Innovation: The Influence of Institutional Context in Large International Participatory Research Projects.” Land Use Policy 61: 276–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.11.027.

- Klerkx, Laurens, Egil Petter Stræte, Gunn-Turid Kvam, Eystein Ystad, and Renate M. Butli Hårstad. 2017a. “Achieving Best-fit Configurations Through Advisory Subsystems in AKIS: Case Studies of Advisory Service Provisioning for Diverse Types of Farmers in Norway.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 23 (3): 213–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2017.1320640.

- Knickel, Marina, Sabine Neuberger, Laurens Klerkx, Karlheinz Knickel, Gianluca Brunori, and Helmut Saatkamp. 2021. “Strengthening the Role of Academic Institutions and Innovation Brokers in Agri-Food Innovation: Towards Hybridisation in Cross-Border Cooperation.” Sustainability 13 (9): 4899. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094899.

- Knierim, Andrea, Pierre Labarthe, Catherine Laurent, Katrin Prager, Jozef Kania, Livia Madureira, and Tim H. Ndah. 2017. “Pluralism of Agricultural Advisory Service Providers – Facts and Insights from Europe.” Journal of Rural Studies 55: 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.07.018.