ABSTRACT

Purpose

This study explores the BioRegio Betriebsnetz (BRB) in Bavaria, a unique policy-initiated, farmer-based knowledge provider network that disseminates knowledge on organic farming and complements agricultural advisory services (AAS). This study aims to identify the characteristics and attributes critical to the successful implementation of knowledge provider networks and make recommendations based on the findings.

Design/Methodology

The data are based on background information from the state and an online questionnaire completed by 22 BRB farmers. Based on the questionnaire results, further in-depth interviews have been conducted among eight of the model farmers.

Findings

Farmers are generally satisfied with the BRB, noting the low amount of extra effort required to participate, which aligns with the network’s purpose. The excellent organization of the supervising authority and possibility of exchanging knowledge with other farmers in the BRB are deemed positive. The results have shown little demand for farmer-to-farmer talks.

Practical implications

Networks such as the BRB require thoughtful selection of model farmers, low levels of bureaucracy while providing good support, and consideration of the local agricultural context.

Theoretical implications

The paper presents an expanded view of knowledge transfer through model farmers in the context of farmer-to-farmer talks. It also identifies the necessary factors for the successful introduction of a knowledge provider network.

Novelty/Significance of the study

The BRB is unique in its design and structure, providing new insights into building knowledge provider networks.

1. Introduction

The EU has recently announced a target to reach 25% organic farming by 2030 (European Commission Citation2021). However, this endeavor is challenging because farmers’ motivation to adopt organic farming is multifactorial (e.g. environmental motives, economic efficiency, farm structure compatibility, secure markets) (Darnhofer, Schneeberger, and Freyer Citation2005; Koesling, Flaten, and Lien Citation2008). Further, organic farming is an innovative practice (Padel Citation2001; Unay Gailhard, Bavorová, and Pirscher Citation2015), significantly influenced by the production and distribution of related knowledge (Rogers Citation2003) while being knowledge-intensive and often non-prescriptive, in addition to exhibiting environmental, agronomic, and socioeconomic complexity (Cristóvão, Koutsouris, and Kügler Citation2012). Farmers primarily obtain knowledge directly from other farmers (peers) (Garforth et al. Citation2003), making on-farm demonstrations (OFDs) involving peer-to-peer contact an important instrument for the transfer of agricultural knowledge (Sutherland and Marchand Citation2021). Consequently, OFDs, which are deeply anchored in agricultural advisory services (AAS) as an advisory method, have garnered attention as an effective instrument for the exchange and transfer of knowledge, technology, and best practices (EU SCAR AKIS Citation2019); the number of EU OFD programs is growing (Ingram et al. Citation2021). The characteristics of knowledge transfer in the context of OFDs have been extensively studied in Europe through several FarmDemo projects (see Sutherland and Marchand Citation2021).

AAS, a part of the Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation System (AKIS), play an essential role in innovation and knowledge dissemination at the individual-farm level (Labarthe Citation2009; Piñeiro et al. Citation2020), involving different actors and structures for organic farming (Österle et al. Citation2016). AAS are diverse, with several service providers within the EU (public, private, farmer-based, non-governmental organizations) (Knierim et al. Citation2017). In previous research, Klerkx (Citation2020) underscored the need to elucidate the diversity inherent in advisory systems and existing sub-systems, and Cristóvão, Koutsouris, and Kügler (Citation2012) highlighted the need for innovative approaches in extension/advisory services, emphasizing the importance of knowledge brokers and participatory processes as well as providing extension-process experiences. As organic farming is observation-, knowledge-, and learning-intensive (Röling and Jiggins Citation1998), requiring that unique measures for innovation and knowledge transfer be applied to specific regions (Leeuwis and van den Ban Citation2004), its development also depends on AAS. Adapting measures for extension/advisory services is needed to promote the spread of sustainable agriculture and requires the involvement of diverse stakeholders to promote social learning as well as the use and dissemination of innovations (Brunori et al. Citation2013; Cristóvão, Koutsouris, and Kügler Citation2012; Moschitz et al. Citation2015).

This work presents a case study of the unique BioRegio Betriebsnetz (BRB) (BioRegio farm network), a novel, adapted advisory approach to AAS, along with its characteristics, implementation, and analysis based on a policy-initiated knowledge network consisting of 100 organic model farms distributed throughout Bavaria from 2012 onwards. The BRB offers model farmers as knowledge providers who transfer their comprehensive knowledge and act as a point of contact for farmers considering the conversion to organic farming as well as for individuals or groups seeking in-depth understanding of organic farming practices. Knowledge transfer occurs during prearranged meetings called farmer-to-farmer talks, herein called OFD, at the model farm.

The objectives of this study were to assess the setup and operating principles of the BRB and conceptualize it in relation to OFD and network structure. Furthermore, the BRB’s practicality was assessed from the perspective of BRB model farmers. This approach is unique, as the BRB reveals new aspects for successful implementation of agricultural knowledge provider networks as political instruments. Previously, the knowledge provider’s perspective has been disregarded; therefore, it is expressly considered in this study. The study findings inform recommendations for future implementation of similar networks aimed at promoting organic farming.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Chapter 2 discusses knowledge transfer within OFDs through peer-to-peer contact and the classification of knowledge types and knowledge networks in agriculture. Chapter 3 presents the BRB case study, followed by evaluation of the state. The results show the characteristics and peculiarities of the BRB and reveal its conceptualization based on OFDs and network structure. Chapter 4 discusses the perspectives of BRB model farmers, and Chapter 5 presents the applicability of the identified networks and summarizes the conclusions drawn from this study.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. Peer-to-peer learning through on-farm demonstrations

Through FarmDemo, the EU has funded projects demonstrating structural and procedural success factors for OFDs (Sutherland and Marchand Citation2021). The OFD combines three important aspects of agricultural knowledge transfer: (1) contact with peers who have similar attitudes and farming styles (Morgan Citation2011), being the most important source of knowledge (Garforth et al. Citation2003); (2) roadside farming and the assessment of skills and management abilities based on other farmers’ fields and practices, an established medium of knowledge transfer (Burton Citation2004); and (3) contact with spatially close model farmers, as local experiential knowledge is highly valuable (Šūmane et al. Citation2018). These mechanisms are used by OFD actors to disseminate tacit and explicit knowledge through peer-to-peer conversation. Within OFDs, farmers are taught agricultural techniques applicable to their own farms (Knapp Citation1916). Using model farms to facilitate this knowledge transfer is a known method (Burton Citation2020) that not only demonstrates the farmer's expertise but also builds the trust of those seeking knowledge (Rust et al. Citation2022). The BRB farmer-to-farmer talks combine these characteristics and can be referred to as OFDs.

Today, model farmers are primarily used in the context of agricultural extension in the global south, where they teach other farmers improved agricultural methods (Franzel et al. Citation2013; Hailemichael and Haug Citation2020; Taylor and Bhasme Citation2018). As illustrated by the evaluation of the BRB for organic farming in the present study, there is renewed interest in model farmers in the global north. This relates to model farmers being described as ‘change agents’ through peer contact and knowledge transfer of region- and production-specific knowledge (Van Poeck, Læssøe, and Block Citation2017) and by providing knowledge of holistic, sustainable farming practices based on agro-ecological processes, organic farming methods and values, and the social function of organic farming (Verhoog et al. Citation2003).

OFDs are an important medium for knowledge exchange among multiple actors in agriculture, contrasting with the classical top-down medium of knowledge transfer from extension agents/researchers to farmers. These new learning conditions shift the responsibility of knowledge acquisition and organization from the teacher to the knowledge seeker while the teacher may also benefit from reciprocal flow of knowledge (Cooreman et al. Citation2018). Cooreman et al. (Citation2021, 714) identified OFDs as transformative learning spaces and suggested increased effort to ensure that ‘the on-farm demonstration is relevant to the situation of the attendees and into application in real-life contexts and incorporation of hands-on experience by attendees.’ Recent studies have revealed that relevance, objectives, audience, and setup are critical aspects of the OFD (Adamsone-Fiskovica et al. Citation2021; Alexopoulos et al. Citation2021; Ingram et al. Citation2018; Pappa et al. Citation2018) and that OFD peer learning is dependent on several factors (Pappa et al. Citation2018; Sutherland and Marchand Citation2021). The transfer of knowledge among peers is highly dependent on the complexity, diversity, and context of the OFD. The demonstrator, who may be a farmer, researcher, advisor, or other certified specialist, is also crucial (Alexopoulos et al. Citation2021), as their characteristics are fundamental to successful OFDs (Adamsone-Fiskovica et al. Citation2021; Franzel et al. Citation2015; Kumar Shrestha Citation2014). Therefore, demonstrator characteristics have made OFDs an advisory method fundamental to many AAS; however, OFDs should not be considered in isolation but always in an adaptive interrelationship with the prevailing AAS, thereby making new approaches to OFDs, as in this study, highly relevant (Ingram et al. Citation2021).

In FarmDemo projects, researchers distinguish the enabling level (setup of advisory landscape and AKIS) and operational levels (practical implementation for successful OFDs) within OFD programs. For the enabling level, the number of demonstrations varies across the EU. Ingram et al. (Citation2021) reported that in the context of AKIS, countries with well-funded AAS particularly have more integrated and extensive OFD programs. They also found that hosting OFD programs provides an opportunity for increased AKIS integration through collaborative work. Reliance on government funding imposes certain constraints on the choice of OFD topics and demonstrator. In contrast, relatively pluralistic AKISs were characterized by more flexible approaches to OFD that could easily respond to emerging needs but were fragmented.

The operational level captures the ‘success factors’ for organizing successful OFDs, summarized by Adamsone-Fiskovica et al. (Citation2021) as the ‘nine Ps,’ identified in an analysis of 24 case studies from the PLAID (Peer-to-peer Learning: Accessing Innovation through Demonstration) project, also part of FarmDemo. The nine Ps are included in the conceptual framework for OFDs developed by the FarmDemo collaboration (Sutherland and Marchand Citation2021), identified as purpose, problem, place, personnel, positioning, program, process, practicality, and post-event engagement () (Adamsone-Fiskovica et al. Citation2021, 644f.)

2.2. Knowledge and knowledge networks in agriculture

The most recent classification of knowledge transferred in the context of OFD has emerged from FarmDemo. In contrast to Polanyi's (Citation1958) most common division of knowledge transferred in agriculture into tacit (implicit) and codified (explicit) knowledge, or Lundvall and Johnson's (Citation1994) division into knowing ‘what,’ ‘why,’ ‘how,’ and ‘who,’ FarmDemo authors link knowledge to learning type. This classification method distinguishes experiential (gaining tacit and explicit knowledge), transformative (changing behaviors and perspectives), and network learning (social interaction and relationship building). Such forms of learning at the operational level are considered ‘peer learning’ and are reflected in the FarmDemo conceptual framework of OFD (Sutherland and Marchand Citation2021). Therefore, the authors have shown the potential of peer contact in OFD programs.

The field of agriculture is complex and diverse, characterized by various aspects aligning with specific network structures. Smedlund (Citation2008) and Sutherland et al. (Citation2017) reported three primary network types: centralized, distributed, and decentralized. Centralized networks constitute a central node through which all knowledge flows. This structure is the most effective for routine problem solving where explicit, standardized knowledge, such as advice on general regulatory issues, is required. Codified knowledge, representing ‘why’ and ‘what,’ is mainly transmitted within this type of network. Knowledge sources such as agricultural advisors serve as central nodes in this context, as they can channel information. This can be individual interactions of farmers with an advisor, who, in turn, interacts with other advisors in their own or different organizations. Conversely, distributed networks are dense conglomerations of links where mostly tacit knowledge is exchanged, equated to ‘communities of practice’ where peers exchange knowledge. They are highly reliant on social capital, meaning the combination of shared norms, values, and understandings that facilitate cooperation within or among groups. The close nature of these relationships tends to foster incremental sharing of innovation and knowledge, driven primarily by experiential knowledge. For example, one network might involve a farmer primarily connected to other farmers. Lastly, decentralized networks have multiple nodal points, connecting various individuals. Decentralized networks foster the exchange of diverse knowledge, often from outside the immediate peer group (weak ties), and are typically associated with the gathering of potential knowledge on future or cutting-edge innovations (Smedlund Citation2008). An example is one farmer with local and distant ties to a broad range of actors (Sutherland et al. Citation2017). However, as Klerkx and Proctor (Citation2013) pointed out, the distinctions of these three network types are often blurred. Advisors and farmers alike draw on both decentralized and distributed networks to stay informed. Thus, the potential for hybrid networks is demonstrated, as revealed in this paper. In addition, this paper highlights the dynamic nature of knowledge transfer within the agricultural field, reflecting the adaptive and responsive strategies employed by those within the sector.

3. Materials and methods

For the BRB case study, a mixed-methods approach was utilized, including collecting background information from state documents, an online questionnaire with BRB model farmers, and in-depth interviews with eight BRB model farmers. The purpose of this approach was to gain a comprehensive understanding of the characteristics and processes involved as well as to capture both the state’s view and farmers’ perceptions of the BRB.

Background data were extracted from brochures, reports, and documents from Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Ernährung, Landwirtschaft und Forsten (Bavarian State Ministry of Food, Agriculture, and Forestry; StMELF) and analyzed to provide supplementary information on the BRB framework, special features, and characteristics. Through email and telephone correspondence with Landesanstalt für Landwirtschaft (LfL) (the State Institute for Agriculture) members responsible for the BRB, further background information on BRB implementation and processes was gathered and comprehension was clarified. In particular, the following topics were discussed: scheduling of visits, process and remuneration of visits, documentation/bureaucracy, selection of farms, network changes, and challenges/limitations. Two calls occurred in January 2020 and June 2023; the first was recorded and transcribed, and the second was noted and supplemented by memory log.

Data were collected by administering an online questionnaire and interviewing eight organic farmers from the BRB. In March 2021, the online questionnaire was sent to all 100 BRB model farmers via LfL, specifically tailored to capture the following information: level of satisfaction of model farmers with the network; effort put into the network; and value, disadvantages, and scope for network improvement. The online questionnaire, comprising three blocks, was adapted in close consultation with LfL and adjusted for feasibility. The first block, featuring general introductory questions, yielded an overview of farm characteristics as well as personal characteristics of the farmer and encouraged survey completion. The second block consisted of simple questions about the farms’ BRB participation and implementation (e.g. length of BRB membership, number of farmer-to-farmer meetings held, and topics discussed at the meetings with a pre-selection informed by LfL). The third block determined the farmers’ opinion of the BRB (satisfaction level, amount of additional work caused by the BRB, and suggested improvements). The reason for selection was asked in certain questions to understand the decision.

The obtained data were used to derive insights from the model farmers’ perspective and to make inferences about the BRB. The online questionnaire addressed all 100 farms via a public email from BRB project coordination at LfL to achieve the highest possible response rate. As the online questionnaire was anonymized, whether it was completed by the eight model farmer interviewees is not known. The questionnaire was accessible online for four months, and the target respondents received a reminder after two months; 22 of the 100 BRB members responded. Two answer sheets were only partially completed, but the indicated questions were used. The author is aware that, due to the small number of responses, no claim to completeness can be made here.

Complementing in-depth data on the insights obtained from the online questionnaire were gathered via the eight semi-structured interviews with BRB model farmers. To ensure a comprehensive representation of farmer views, farmers from districts with varying rates of organic farming expansion, including low (0%–6%), moderate (7%–15%), and high (16%–30%) rates, based on data from 2019, were contacted. Fifteen farms from four administrative districts (Central Franconia, Lower Bavaria, Swabia, and Upper Bavaria) were contacted, resulting in the eight farm managers willing to be interviewed. The farms differed with respect to their basic setting, district, and types of farming and cultivation techniques used, and represented all four major organic farmers’ associations (OFAs) (Bioland, Biokreis, Demeter, and Naturland). The interviews were conducted in April and May 2021. Seven of the eight interviews were recorded, but for one, recording was not permitted, and the interviewee’s responses were manually recorded. The interviews were then transcribed. Next, all interviews were coded using MAXQDA as follows: satisfaction with the BRB, additional effort toward the BRB, strengths of the BRB, weaknesses of the BRB, suggestions for improvement, and other remarks regarding the BRB.

4. Introduction of the case study BioRegio Betriebsnetz (BRB)

The BRB lends itself to a single-case study design because of its unique nature (Yin Citation2018). The BRB was long considered unique in its approach and structure and was used as a template for ÖkoNetz BW in Baden-Württemberg, which was founded in 2023.

4.1. Bioregio Betriebsnetz

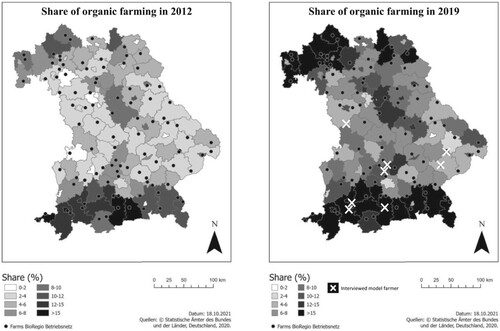

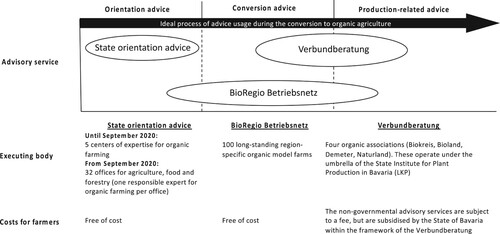

The BRB network comprises 100 organic model farms distributed throughout Bavaria (), an established measure in 2013 of the BioRegio Bayern 2020 program. The purpose of the BRB is to foster knowledge transfer to farmers interested in conversion to organic farming, intending to lower the barriers of engagement for conventional farmers by offering peer-to-peer contact in the form of OFDs from model farmers without obligations (StMELF 2017). Questions from those seeking knowledge can be answered and, if necessary and desired, clarified through demonstration and explanation of farm practice. The BRB complements state orientation advice and Verbundberatung in Bavaria (), thus becoming part of the Bavarian AKIS, which is predominantly shaped by state organizations managed by StMELF. Within StMELF, the state departments of Food, Agriculture, and Forestry (Ämter für Ernährung, Landwirtschaft und Forsten, or ÄELF) coordinate agricultural advice and serve as the first contact point. ÄELF collaborates with accredited advisory partners (farmer-based organizations, non-governmental advisory organizations, and private organizations) called the Verbundberatung (Birke et al. Citation2021).

Figure 1. Spatial distribution of organic farming in Bavaria in 2012 (on the left) and 2019 (on the right). (Source: Statistische Ämter des Bundes und der Länder, Deutschland 2020).

Figure 2. Agricultural advisory services (AAS) for organic farming in Bavaria for each phase in the conversion process (Source: LfL 2020).

Advice for organic farming in Bavaria varies and is tailored for farmers interested in switching to or already practicing organic farming. According to LfL, farmers should seek advice when planning conversion to organic farming (LfL Citation2020). There are two phases during conversion and two corresponding AAS as follows: (1) ‘orientation advice’ offered by ÄELF (no cost), and (2) ‘conversion- and production-related advice’ offered by OFAs, which either entails a partially state-subsidized fee or is free for OFA members of Bioland, Biokreis, Demeter, and Naturland (). The advice provided by the OFAs is compiled in Landeskuratorium für pflanzliche Erzeugung (the State Board for Plant Production in Bavaria).

4.2. State’s evaluation of the BioRegio Betriebsnetz

According to StMELF, the BRB is a successful part of the BioRegio Bayern 2020 program (Kaniber Citation2021). The LfL 2020 progress report stated that the BRB ‘is a valuable instrument for supporting existing organic farms in the further development of their competitiveness and for enabling additional farms to convert to organic farming’ (Sadler et al. Citation2020, 179). Kaniber (Citation2021) and Sadler et al. (Citation2020) revealed that the number of farm talks increased in the beginning and then plateaued. However, a declining trend was observed during the pandemic years as peer-to-peer contact was hindered. The approximate number of participants increased steadily. Notably, ‘others’ was the second strongest audience group, indicating a growing demand for information on organic farming from actors outside the agricultural sector. While visits of organic farming academies and organic farming colleges are to be expected, the BRB notably offers an introduction to organic farming for young people at agricultural and vocational schools (). The state expenditures for BRB farmer financial compensations declined from €24,887 in 2019 to €14,066 in 2020 owing to reduced demand. The BRB is generally positively portrayed, as concluded from figures on the development of organic farming and the demand for the BRB.

Table 1. Demand for farm visits and number of participants of the BRB from 2013 to 2020; the number of participants is only documented with active indication by the farmer, and each participant counts individually (Kaniber Citation2021; Sadler et al. Citation2020).

Statistical BRB data from 2012 to 2020 demonstrate approximately 86.6% growth in the land area of organic farming (), whereas the number of organic farms increased by approximately 67.8%. The share of organic farming increased from 6.4% in 2012 to 12.1% in 2020, whereas, in the same period, the total utilized agricultural area declined by 1.5% (LfL Citation2020; DeStatis Citation2022). The spatial distribution of organic farming in Bavaria changed accordingly, with slight differences in all districts and district-free cities ().

5. Results

5.1. Background, processes, and implementation

The BRB model farms were selected based on OFA or supervising organic advisor recommendations; at that time, one person from each of Bavaria’s five centers of expertise for organic farming suggested suitable farmers. In addition to the farmer's excellent agricultural and economic expertise, communication skills were crucial. The selection committee included individuals from StMELF, LfL, Landesvereinigung für den ökologischen Landbau in Bayern e.V. (the Bavarian Association for Organic Farming), and all four OFAs (Biokreis, Bioland, Demeter, and Naturland). In addition to the selection criteria, model farms were selected to ensure that, to the greatest extent possible, each of the 96 districts and district-free cities had one model farm and represented various farming methods, husbandry practices, and specialty crops.

Within the BRB, bureaucracy on both sides is minimized as follows. An appointment with one farm is arranged through the supervising institution, LfL. The model farms register their capacity for OFDs with LfL in advance, depending on the time of year and availability. LfL then schedules an OFD and informs the farm of the number of visitors. After the OFD, the farmer faxes or e-mails LfL a form with visitor names, if documented. During the second phone call, the LfL contact person stated that, depending on the preparation effort and number of participants, the model farm is compensated for the effort associated with tariff payments for master farmers (approximately €35–100). The tariff is paid from the Bavarian government's BRB project budget; however, the funding amount covers the entire BRB and not individual farms; therefore, certain farms conduct significantly more OFDs than others. The LfL contact also stated that there is a high variance in demand for individual BRB farms; some have a very high demand, and others have almost no demand at all. This can be explained by the characteristics of the farms, particularly the type of husbandry or cultivation, and the publicity of individual farmers in surrounding districts. In addition, LfL found that the rarer a type of husbandry, e.g. sheep, the more distant would be the inquiries, even from outside Bavaria. The only additional obligations for BRB farmers are the annual meetings organized by LfL, where all BRB farmers are informed about new findings and developments in organic farming. Owing to the diversity of farms, some topics at the meetings may not correspond to the farm profile, although an attempt is made to cover a wide range of topics. Neither the model farmers nor LfL document the personal data of visitors of OFDs within the BRB; thus, it is nearly impossible to analyze the effects experienced by the visitors.

5.2. Conceptualizing the BioRegio Betriebsnetz

5.2.1. On-farm demonstrations

In contrast to the FarmDemo OFDs analyzed by Adamsone-Fiskovica et al. (Citation2021), who subsequently identified the nine Ps, based on the interviews with the farmers and LfL, the situation for OFDs under the BRB is different (). In the BRB, OFDs are not specifically designed for knowledge exchange between multiple actors with different backgrounds. Actor diversity is usually low (farmer to farmer or farmer to interest group with similar background), which also influences the type of knowledge transfer. In OFDs, knowledge flows primarily from the BRB farmer to the knowledge-seeking farmer although reciprocal knowledge exchange also occurs. In the case of interest groups, a teacher–student relationship exists in the exchange of knowledge from the farmer to the knowledge-seeking group, partly because the individual group member has less practical experience than the BRB farmer. In the BRB, the preparation of OFDs and means of knowledge exchange are simpler; however, this does not reduce the demonstration quality. For example, OFDs are not specially prepared, as problems and questions are only revealed to the BRB farmer during the OFD itself and must be handled spontaneously. Further, there is little need to prepare the locations, as communication virtually occurs in the ‘everyday life’ of BRB farmers. For group visits, relatively more preparation is needed to ensure adequate conditions for group knowledge transfer. The actual implementation is left to the BRB farmer, as they know the existing conditions best.

Table 2. Nine Ps influencing the success of OFDs according to Ademsone-Fiskovica et al. (Citation2021, 644f.) and the respective situation in BRB OFDs.

5.2.2. Knowledge provider network structure

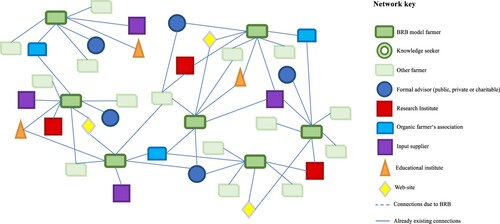

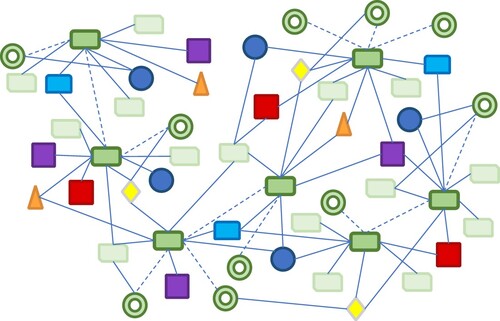

BRB farmers have great knowledge and connections with various actors in agriculture because of their background and the criteria used to select them. Consequently, farmers’ knowledge, whether categorized according to Lundvall and Johnson's (Citation1994) typology or Sutherland and Marchand's (Citation2021) type of learning, is extensively diverse. BRB farmers can answer questions that require knowledge on ‘what,’ ‘why,’ ‘how,’ and ‘who,’ while also engaging in and implementing experiential, transformative, and network learning. Even if they cannot answer a question, they likely know who to contact. The assessment of the knowledge network is similar in that different types of knowledge are associated with different networks. Because the BRB is not a ‘naturally’ grown network but a politically implemented network designed to transfer knowledge from model farmers to knowledge-seeking farmers, its network structure differs as a combination of known agricultural network types (Sutherland et al. Citation2017); thus, it is considered a knowledge provider network (for organic farming). The BRB has the characteristics of a distributed network because a high amount of tacit knowledge is transmitted, and the network is regarded as a ‘community of practice’ or ‘network of practice.’ However, the social capital on which such networks depend is limited in the BRB because it is based on close personal relationships, which are scarce among BRB farmers. Such relationships between BRB farmers and knowledge seekers do not exist but could emerge. Therefore, the BRB also has the characteristics of a decentralized network, as it has multiple nodes connecting different individuals. Over the years, the BRB model farmers have built their own knowledge network through different sources and thus also serve as knowledge nodes. Therefore, they rely on their own individual knowledge network to obtain needed information (). As each farmer and farm is unique, the actors differ in their personal knowledge network. This facilitates the dissemination of different knowledge types and qualifies them as BRB model farms. The connections to other actors that BRB farmers gain through BRB activities also expand their personal network. It thus combines a distributed network structure with a decentralized network structure, allowing for diverse individuals (peers and groups) to connect (). The evaluation and embedding of the BRB are necessary for its comprehensive elucidation and, based on this, for classifying and understanding the following findings. The uniqueness of the BRB provides the opportunity to capture additional aspects for the successful implementation of such a network as a policy tool.

Figure 3. An abstract representation of knowledge networks of model farmers as it would have looked before the BRB was installed. Based on Sutherland et al. (Citation2017).

Figure 4. Structure visualization of the BRB, where knowledge seekers are added as actors. A knowledge provider network is created. Based on Sutherland et al. (Citation2017).

5.3. Perspectives of BRB farmers

Insights into the BRB farmers’ perspectives were obtained from 22 online questionnaires. The eight in-depth interviews provided additional insights.

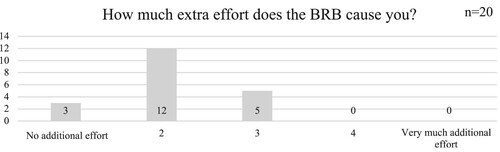

The additional effort for model farmers as a result of the BRB is reported as being non-existent or low. No respondents perceived a high level of additional effort (). The farmers mentioned that they allowed farm visits before the BRB and already served as an advisory contact point for farmers interested in switching to organic farming. ‘I like to take the time for the farmer-to-farmer talks. They are always interesting conversations. You also learn something from others, even just little things,’ stated one farmer, further demonstrating their open-mindedness and indicating that knowledge transfer is not exclusively unilateral.

Seventeen of 22 farmers stated that the ratio of additional effort to the benefit of the BRB is balanced; one denied this balance, and two were unsure. Most BRB farmers, therefore, did not consider their role as a knowledge resource in the BRB to be a waste of time.

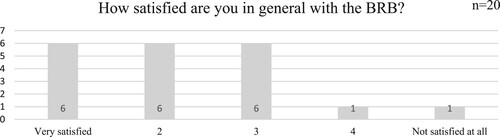

Satisfaction among respondents varied widely between very satisfied, fairly satisfied, and satisfied (). The farmers gave the following reasons for their choice. Among the very and fairly satisfied respondents, the reasons given were the excellent supervision of the BRB by LfL, the opportunity to interact with other BRB farmers, and that through OFDs from vocational and agricultural schools, future farm managers can obtain insight into organic farming. Among the satisfied respondents, the reasons included that they had previous experience as consultants, that the initial euphoria had been lost over the years, and that the BRB was seen more as ‘just another network.’ Unsatisfied farmers highlighted challenges such as animal welfare or biodiversity. The compensation for OFDs within the BRB is also important, as one farmer mentioned in an interview, ‘it is about time we got paid for what we have been doing for so long.’

All eight farmer interviewees believed that the basic mechanisms and intentions of the BRB have been effectively implemented. One farmer said ‘the transfer of knowledge should be the focus [of the BRB], and if you assume that, [the] BRB is ok.’ In addition, based on the online questionnaire responses, the following topics were the most frequently addressed by the knowledge seeker: economic efficiency, cultivation methods, motivation to farm organically, production technology, and animal husbandry/stable construction requirements. When asked about the topics that farmers felt were important but never addressed, three were mentioned: social policy, animal welfare/biodiversity, and workload. According to data obtained from the online questionnaire and interviews, the production-specific knowledge of BRB farmers is highly practical because it is generated through personal experimentation and exchanges with organic-farmer colleagues. The questionnaire responses indicate that knowledge on topics beyond the farm is mostly obtained directly through OFA meetings at regional and local scales and supplemented by OFA circulars. Additionally, farmers mentioned using exchanges with advisors, print media, and the internet as sources of knowledge on organic farming and tacitly through their exchanges with other farmers.

Many interviewed farmers also hold positions such as board members at dairy firms, co-founders of producer rings, and OFA representatives and may also be involved in local politics. Such activities expand their network and knowledge, validating their qualification as model farmers. During the eight interviews, the idealistic attitude and willingness and intrinsic motivation of BRB farmers to support the development of organic farming were evident in the enthusiastic way they engaged in the interviews.

Although the inter-network exchange is not a goal set by the BRB, 12 of the 22 online questionnaire respondents stated that they benefit from the inter-network exchange. Three stated that they benefit from annual meetings, two from the support for public relations work, and one each of exclusive information and the Competence Center Organic Farming newsletter. Sixteen of the 22 BRB members stated their desire for more inter-network exchange. In addition, BRB farmers indicated they value each other's opinions and exchanges and can also be an inspiration, as one BRB farmer said: ‘Demeter farmers are different and have different approaches. I always find that quite exciting.’ This does not necessarily mean that they switch to Demeter agriculture, but it indicates their openness to other approaches and, thus, broadens their horizons of knowledge. Seventeen farmers stated that they are acquainted with more than 15 organic farmers within their district.

Additionally, although the online questionnaire results presented the BRB in a positive light from the farmers’ point of view, the interviews revealed indifference among the farmers toward related policies. Although all were in favor of the BRB, they felt that the network’s potential has not been exhausted but did not provide explicit suggestions for improvement. They generally expect more tools and support for the development of organic farming. In addition, the recently announced target of 30% organic farming in Bavaria by 2030 was described by certain farmers in the interviews as ‘unattainable’ if the policy continues to support organic farming at the current level; as one farmer said: ‘I have to say, they [the state of Bavaria] will not achieve anything this way. That is why they will not reach their percentages. It will not work. Not a chance.’ When asked how many farmer-to-farmer talks were held, the number ranged from 2 to 50, with the average of all (n = 19) being just over 17. However, low demand for OFDs was reported within the interviews.

Overarching tension and indifference among organic farmers with respect to politics, such as too little appreciation or preference for conventional farmers, was reflected in the enormous influence of Bavarian Farmers’ Association (Bauernverband). Farmers complained about the lack of representation of organic agriculture; particularly, the need for structural change to reach the 30% target was mentioned. One farmer said, ‘If I want more organic [farming], then more resources have to be used for it. For me that means 30% [staff] in government and other institutions.’

6. Discussion

The farmer's perspective adds value by showing the daily practical implementation and identifying the problems associated with the BRB. The evaluation of the network by the state (Kaniber Citation2021) has a political background, which means that the BRB is not questioned but only presented as a success; the figures in the report are not presented in perspective. Therefore, it is difficult to assess the BRB’s actual impact and potential. The potential of the BRB is only indicated by the additional capacity for OFDs. This limitation calls for further research on the BRB.

The level of satisfaction of BRB farmers, identified in this work as a crucial aspect for a functioning BRB-type network, is predominantly high yet variable. Excellent organization and communication on the part of the supervising institution is therefore a basic prerequisite for a high level of satisfaction. However, the resulting exchange among farmers is an advantage for the farmers, which increases their satisfaction level. Therefore, certain farmers associate the level of satisfaction with a benefit they receive. It is speculative whether farmers would associate the exchange among themselves with the level of satisfaction if the general communication and organization were poor. However, extra work required to participate in the BRB, which was generally low, was not cited as a reason for the level of satisfaction. Therefore, as observed by Adamsone-Fiskovica et al. (Citation2021), the pre-selection of farmers is important to identifying those interested in participating in knowledge transfer within OFDs, who may have previously done so in a similar way and who do not consider it to be much effort.

In addition to their various knowledge sources (meetings, media, advisors), their experience underscores the importance of the practical nature of knowledge for BRB farmers. This in turn highlights the value of organic farming experiential learning. In addition, farmers would like to see more interaction among themselves in the BRB, although they mentioned that they already benefit from interaction with other BRB farmers. Because exchange between BRB farmers is not a goal of the network, this would have to come from their own initiative.

One aspect that did not emerge from the questionnaire or the state’s evaluation was the generally low utilization of the BRB, evident from interviewee responses. The variation in demand among model farmers, as reported by LfL, also complicates the estimation of the BRB’s potential, as there is less demand for rare livestock or crop species. Nevertheless, there is capacity for increased demand for BRB farmers. In addition, the low budget of the BRB is a major advantage over other policy measures for AAS. Further analysis to assess spatial demand patterns, how often each BRB farmer is requested, or how the BRB visit affects the visitor’s decisions is not feasible, as LfL does not record visitor information or the number of talks. Spatial analysis would provide reference for region-specific adjustments. However, further inquiry with LfL revealed that the documentation of each talk was too time consuming. The lack of detailed documentation by LfL limits the assessment of spatial in-depth performance of the BRB.

The low, although not atypical, response rate of approximately 20% should be considered. Although these farmers are open and interactive, one possible explanation for the low response rate could be a general aversion to questionnaires. Therefore, the question of representativeness must be raised. The results provide insights but may not reflect the full range of perspectives of BRB farmers. Despite the author's collaboration with LfL, the response rate was low. This is surprising, given the model farmers’ interest in knowledge transfer. It can also be inferred from this behavior that there is a dislike for politics and institutions, as was also noted during the interviews. However, there was no aversion towards the BRB per se, because on the one hand, BRB is considered a means for organic farming and provides compensation, but on the other hand, the interference, i.e. coordination, of LfL is very low. Hence, the transfer of knowledge to other farmers or interest groups is not resisted.

Because of its uniqueness, the BRB complements studies on network structure and knowledge networks. Unlike Bailey et al. (Citation2006), the value of information sources is not given, but similar networks for farmers are revealed (Bailey et al. Citation2006). Based on the network structures from the work of Madureira et al. (Citation2015), the BRB structure integrates different characteristics from the networks. A clear demarcation of the networks in which farmers are integrated, as shown by the authors, is hardly possible owing to their multiple sources of knowledge and interactions in the real world (Madureira et al. Citation2015). The BRB is also unique compared with demonstration programs within the EU analyzed by Ingram et al. (Citation2021). The on-demand OFDs provided by model farmers to promote organic farming in an increasingly pluralistic AAS, organized by a state institution, make the BRB a highly interesting and promising example for the future.

7. Realization and recommendations

The uniqueness of the BRB offers new insights into the successful implementation of knowledge provider networks. The responsibility of acquiring information is shifted to the knowledge seeker, such that the imparted knowledge is problem-specific and information is, thus, directly imparted. In this case, the success principles of OFDs (the nine Ps) differ from those reported by Adamsone-Fiskovica et al. (Citation2021), requiring a reassessment of the BRB type of OFD.

The findings of the present study provide reference for the following five recommendations regarding the implementation of similar knowledge provider networks: (1) There is a need to understand local context; it is important to know the policy objectives, general barriers, and challenges with respect to regional organic agriculture. Involving different stakeholders in the agricultural sector and organic farming can help avoid upstream problems. (2) There is a need to assess the local AAS to identify shortcomings; depending on what is offered, a knowledge provider network such as the BRB may not fill this gap and may, therefore, be obsolete. Nevertheless, free knowledge by model farmers through easily arranged meetings is welcome. (3) Model farmers must be carefully selected; the selection process is essential. In addition to having excellent agricultural and economic skills, farmers must be willing to share their knowledge. (4) Institutional support is required to handle the coordination and bureaucracy associated with OFDs and compensation; less additional effort from farmers translates into less frustration, making OFD evaluation through feedback unfeasible. (5) Finally, public relations should be considered; without awareness of the knowledge provider network, it can hardly be used. Awareness should be promoted through print media, social media, the internet, and word of mouth. However, some of these approaches require funding, which may be insufficient depending on the budget.

8. Conclusion

This work highlights the importance of networks for the dissemination of knowledge for sustainable forms of agriculture by presenting a case study of the BRB knowledge provider network in Bavaria, established as a complementary building block for the agricultural advisory service of organic farming. The BRB primarily facilitates knowledge transfer among farmers (peer-to-peer) to support the process of conversion to organic farming and utilizes OFDs to offer the benefit of knowledge on organic farming from model farmers. The diverse knowledge base among BRB farmers and their extensive connections with various actors in the agricultural sector underscore their central role as knowledge disseminators for organic farming.

Data from the state demonstrated an increasing demand for the BRB. In line with the generally growing organic farm-land area in Bavaria, the government is developing a growing interest in organic agriculture and considers the BRB as an important building block for this development. Model farmers demonstrated a high degree of satisfaction with the BRB and, in combination with their intrinsic motivation to promote organic farming, the effectiveness of such knowledge provider networks for sustainable agriculture is highlighted.

However, the farmer perspective also revealed problems and weaknesses, indicating that demand for OFDs varies widely and is generally perceived to be low; moreover, the model farmers would like to have more interaction and exchange with each other. However, this is not provided for in the BRB, yet emphasizes the importance of knowledge exchange with peers. There is little resistance to the BRB in that it was regarded as a remarkable practice, yet general dissatisfaction was expressed with the policy agenda related to organic farming development.

Networks like the BRB play a crucial role in the evolving landscape of organic farming and increasing demand for sustainable agricultural practices. The success of such networks depends on integrating different knowledge types, effectively engaging stakeholders, and aligning with regional and national agricultural objectives. As the agricultural sector moves toward increasing sustainability, the findings of this study provide valuable guidance for policy makers, educators, and farmers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kilian Hinzpeter

Kilian Hinzpeter is currently working on his Ph.D. at the Research and Teaching Unit ‘Economic Geography’ at Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich. His focus is on organic farming and its transformative performance and capacity, with a particular interest in knowledge transfer and conversion decision making. He obtained his master degree at the University of Innsbruck, Austria (2017).

References

- Adamsone-Fiskovica, Anda, Mikelis Grivins, Rob J. F. Burton, Boelie Elzen, Sharon Flanigan, Rebekka Frick, and Claire Hardy. 2021. “Disentangling Critical Success Factors and Principles of On-Farm Agricultural Demonstration Events.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 27 (5): 639–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2020.1844768.

- Alexopoulos, Y., E. Pappa, I. Perifanos, F. Marchand, H. Cooreman, L. Debruyne, H. Chiswell, J. Ingram, and A. Koutsouris. 2021. “Unraveling Relevant Factors for Effective on Farm Demonstration: The Crucial Role of Relevance for Participants and Structural Set Up.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 27 (5): 657–676. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2021.1953550.

- Bailey, Alison, Chris Garforth, Brian Angell, Tricia Scott, Jason Beedell, Sam Beechener, and Ram Bahadur Rana. 2006. “Helping Farmers Adjust to Policy Reforms through Demonstration Farms: Lessons from a Project in England.” Journal of Farm Management 12 (10): 613–625.

- Birke, Fanos, Sangeun Bae, Annkathrin Schober, Maria Gerster-Bentaya, Andrea Knierim, Pablo Asensio, Margret Kolbeck, and Carola Ketelhodt. 2021. AKIS and Advisory Services in Germany - Report for the AKIS Inventory (Task 1.2) of the I2connect Project. I2connect Interactive Innovation.

- Brunori, Gianluca, Dominique Barjolle, Anne-Charlotte Dockes, Simone Helmle, Julie Ingram, Laurens Klerkx, Heidrun Moschitz, Gusztáv Nemes, and Talis Tisenkopfs. 2013. “CAP Reform and Innovation: The Role of Learning and Innovation Networks.” EuroChoices 12 (2): 27–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/1746-692X.12025.

- Burton, Rob J. F. 2004. “Seeing Through the ‘Good Farmer’s’ Eyes: Towards Developing an Understanding of the Social Symbolic Value of ‘Productivist’ Behaviour.” Sociologia Ruralis 44 (2): 195–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.2004.00270.x.

- Burton, Rob J. F. 2020. “The Failure of Early Demonstration Agriculture on Nineteenth Century Model/Pattern Farms: Lessons for Contemporary Demonstration.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 26 (2): 223–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2019.1674168.

- Cooreman, Hanne, Lies Debruyne, Joke Vandenabeele, and Fleur Marchand. 2021. “Power to the Facilitated Agricultural Dialogue: An Analysis of on-Farm Demonstrations as Transformative Learning Spaces.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 27 (5): 699–719. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2021.1969958.

- Cooreman, Hanne, Joke Vandenabeele, Lies Debruyne, Julie Ingram, Hannah Chiswell, Alex Koutsouris, Eleni Pappa, and Fleur Marchand. 2018. “A Conceptual Framework to Investigate the Role of Peer Learning Processes at On-Farm Demonstrations in the Light of Sustainable Agriculture.” International Journal of Agricultural Extension Special Issue: 13th International Farming Systems Association (IFSA) Symposium, Greece: 91–103.

- Cristóvão, Artur, Alex Koutsouris, and Michael Kügler. 2012. “Extension Systems and Change Facilitation for Agricultural and Rural Development.” In Farming Systems Research into the 21st Century: The New Dynamic, edited by Ika Darnhofer, David Gibbon, and Benoît Dedieu, 201–227. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4503-2_10.

- Darnhofer, Ika, Walter Schneeberger, and Bernhard Freyer. 2005. “Converting or Not Converting to Organic Farming in Austria:Farmer Types and Their Rationale.” Agriculture and Human Values 22 (1): 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-004-7229-9.

- DeStatis (Statistisches Bundesamt). 2022. “41141-04-02-4:Landwirtschaftliche Betriebe Insgesamt Sowie Mit Ökologischem Landbau Und Deren Landwirtschaftlich Genutzte Fläche (LF) Und Viehbestand - Jahr - Regionale Tiefe: Kreise Und Krfr. Städte.” https://www.regionalstatistik.de/genesis//online?operation=table&code=41141-04-02-4&bypass=true&levelindex=1&levelid=1676289673399#abreadcrumb.

- European Commission. 2021. “Action Plan for the Development of Organic Production - Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions.” https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:13dc912c-a1a5-11eb-b85c-01aa75ed71a1.0003.02/DOC_1&format=PDF.

- EU SCAR AKIS. 2019. Preparing for Future AKIS in Europe. Brussels: European Commission.

- Franzel, Steven, Ann Degrande, Evelyne Kiptot, Josephine Kirui, Jane Kugonza, John Preissing, and Brent Simpson. 2015. “Farmer-to-Farmer Extension.” Note 7. GFRAS Good Practice Notes for Extension and Advisory Services. GFRAS: Lindau, Switzerland.

- Franzel, Steven, Charles Wambugu, Tutui Nanok, and Ric Coe. 2013. The “Model Farmer” Extension Approach Revisited: Are Expert Farmers Effective Innovators and Disseminators? Proceedings of the Conference on Innovation in Extension, November 15-18, 2011. Nairobi.

- Garforth, Chris, Brian Angell, John Archer, and Kate Green. 2003. “Fragmentation or Creative Diversity? Options in the Provision of Land Management Advisory Services.” Land Use Policy 20 (4): 323–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-8377(03)00035-8.

- Hailemichael, Selam, and Ruth Haug. 2020. “The Use and Abuse of the ‘Model Farmer’ Approach in Agricultural Extension in Ethiopia.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 26 (5): 465–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2020.1757475.

- Ingram, Julie, Hannah Chiswell, Jane Mills, Lies Debruyne, Hanne Cooreman, Alex Koutsouris, Yiorgos Alexopoulos, Eleni Pappa, and Fleur Marchand. 2021. “Situating Demonstrations within Contemporary Agricultural Advisory Contexts: Analysis of Demonstration Programmes in Europe.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 27 (5): 615–638. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2021.1932534.

- Ingram, Julie, Hannah Chiswell, Jane Mills, Lies Debruyne, Hanne Cooreman, Alex Koutsouris, Eleni Pappa, and Fleur Marchand. 2018. “Enabling Learning in Demonstration Farms: A Literature Review.” International Journal of Agricultural Extension Special Issue: International Farming Systems Symposium (IFSA): 29–42.

- Kaniber, Michaela. 2021. “Beschluss Des Bayerischen Landtags Vom 12.11.2020, Drs. 18/11361; Mehr Bio Für Bayern – Jahresbericht Über Die Ökologische Landwirt- Schaft, Verarbeitung Und Vermarktung in Bayern”.

- Klerkx, Laurens. 2020. “Advisory Services and Transformation, Plurality and Disruption of Agriculture and Food Systems: Towards a New Research Agenda for Agricultural Education and Extension Studies.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 26 (2): 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2020.1738046.

- Klerkx, Laurens, and Amy Proctor. 2013. “Beyond Fragmentation and Disconnect: Networks for Knowledge Exchange in the English Land Management Advisory System.” Land Use Policy 30 (1): 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2012.02.003.

- Knapp, Bradford. 1916. “Education through Farm Demonstration.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 67 (1): 224–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/000271621606700130.

- Knierim, Andrea, Pierre Labarthe, Catherine Laurent, Katrin Prager, Jozef Kania, Livia Madureira, and Tim Hycenth Ndah. 2017. “Pluralism of Agricultural Advisory Service Providers – Facts and Insights from Europe.” Journal of Rural Studies 55 (October): 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.07.018.

- Koesling, Matthias, Ola Flaten, and Gudbrand Lien. 2008. “Factors Influencing the Conversion to Organic Farming in Norway.” International Journal of Agricultural Resources, Governance and Ecology 7 (1/2): 78. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJARGE.2008.016981.

- Kumar Shrestha, Shiva. 2014. “Decentralizing the Farmer-to-Farmer Extension Approach to the Local Level.” World Journal of Science, Technology and Sustainable Development 11 (1): 66–77. https://doi.org/10.1108/WJSTSD-08-2013-0028.

- Labarthe, Pierre. 2009. “Extension Services and Multifunctional Agriculture. Lessons Learnt from the French and Dutch Contexts and Approaches.” Journal of Environmental Management 90 (May): S193–S202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2008.11.021.

- Leeuwis, Cees, and A. W. van den Ban. 2004. Communication for Rural Innovation: Rethinking Agricultural Extension. 3rd ed. Oxford: Ames, Iowa: Blackwell Science ; Iowa State Press, for CTA.

- LfL (Bayerische Landesanstalt für Landwirtschaft). 2020. Umstellung Auf Ökologischen Landbau - Information Für Die Praxis in Bayern. LfL-Information. Freising-Weihenstephan: Institut für Ökologischen Landbau, Bodenkultur und Ressourcenschutz, Kompetenzzentrum Ökolandbau.

- Lundvall, Bengt-äke, and Björn Johnson. 1994. “The Learning Economy.” Journal of Industry Studies 1 (2): 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/13662719400000002.

- Madureira, Lívia, Timothy Koehnen, Dora Ferreira, Miguel Pires, Artur Cristóvão, and Alberto Baptista. 2015. Designing, Implementing and Maintianing Agricultural/Rural Networks to Enhance Farmers’ Ability to Innovate in Cooperation with Other Rural Actors. Final Synthesis Report for AKIS on the Ground: Focusing Knowledge Flow Systems (WP4) of the PRO AKIS. www.proakis.eu/publicationsandevents/pubs.

- Morgan, Selyf Lloyd. 2011. “Social Learning among Organic Farmers and the Application of the Communities of Practice Framework.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 17 (1): 99–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2011.536362.

- Moschitz, Heidrun, Dirk Roep, Gianluca Brunori, and Talis Tisenkopfs. 2015. “Learning and Innovation Networks for Sustainable Agriculture: Processes of Co-Evolution, Joint Reflection and Facilitation.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 21 (1): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2014.991111.

- Österle, Nina, Alex Koutsouris, Yannis Livieratos, and Emmanuil Kabourakis. 2016. “Extension for Organic Agriculture: A Comparative Study between Baden-Württemberg, Germany and Crete, Greece.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 22 (4): 345–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2016.1165711.

- Padel, Susanne. 2001. “Conversion to Organic Farming: A Typical Example of the Diffusion of an Innovation?” Sociologia Ruralis 41 (1): 40–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9523.00169.

- Pappa, Eleni, Alex Koutsouris, Julie Ingram, Lies Debruyne, Hanne Cooreman, and Fleur Marchand. 2018. “Structural Aspects of On-Farm Demonstrations: Key Considerations in the Planning and Design Process.” International Journal of Agricultural Extension Special Issue: 13th International Farming Systems Association (IFSA) Symposium, Greece: 79–90.

- Piñeiro, Valeria, Joaquín Arias, Jochen Dürr, Pablo Elverdin, Ana María Ibáñez, Alison Kinengyere, Cristian Morales Opazo, et al. 2020. “A Scoping Review on Incentives for Adoption of Sustainable Agricultural Practices and Their Outcomes.” Nature Sustainability 3 (10): 809–820. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-00617-y.

- Polanyi, Michael. 1958. Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy. London, UK: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Rogers, Everett M. 2003. Diffusion of Innovations. 5th ed. New York: Free Press.

- Röling, Niels, and Janice Jiggins. 1998. “The Ecological Knowledge System.” In Facilitating Sustainable Agriculture: Participatory Learning and Adaptive Management in Times of Environmental Uncertainty, edited by Niels Röling, and M. A. E. Wagemakers, 283–311. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rust, Niki A., Petra Stankovics, Rebecca M. Jarvis, Zara Morris-Trainor, Jasper R. de Vries, Julie Ingram, Jane Mills, et al. 2022. “Have Farmers Had Enough of Experts?” Environmental Management 69 (1): 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-021-01546-y.

- Sadler, Thomas, Melanie Wild, Harald Ulmer, Cordula Rutz, and Klaus Wiesinger. 2020. “Sieben Jahre BioRegio Betriebsnetz Bayern - Eine Zwischenbilanz.” In Angewandte Forschung Und Entwicklung Für Den Ökologischen Landbau in Bayern, Öko-Landbautag 2020, edited by LfL (Bayerische Landesanstalt für Landwirtschaft) and University of Applied Science Weihenstephan-Triesdorf, 4/2020, 177–181. Freising-Weihenstephan. https://www.lfl.bayern.de/mam/cms07/publikationen/daten/schriftenreihe/oeko-landbautag-2020-lfl-schriftenreihe.pdf.

- Smedlund, Anssi. 2008. “The Knowledge System of a Firm: Social Capital for Explicit, Tacit and Potential Knowledge.” Journal of Knowledge Management 12 (1): 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1108/13673270810852395.

- StMELF (Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Ernährung, Landwirtschaft und Forsten). 2017. BioRegio Bayern 2020 - Eine Initiative Der Bayerischen Staatsregierung. München.

- Šūmane, Sandra, Ilona Kunda, Karlheinz Knickel, Agnes Strauss, Talis Tisenkopfs, Ignacio des Ios Rios, Maria Rivera, Tzruya Chebach, and Amit Ashkenazy. 2018. “Local and Farmers’ Knowledge Matters! How Integrating Informal and Formal Knowledge Enhances Sustainable and Resilient Agriculture.” Journal of Rural Studies 59 (April): 232–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.01.020.

- Sutherland, Lee-Ann, Lívia Madureira, Violeta Dirimanova, Malgorzata Bogusz, Jozef Kania, Krystyna Vinohradnik, Rachel Creaney, Dominic Duckett, Timothy Koehnen, and Andrea Knierim. 2017. “New Knowledge Networks of Small-Scale Farmers in Europe’s Periphery.” Land Use Policy 63 (April): 428–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.01.028.

- Sutherland, Lee-Ann, and Fleur Marchand. 2021. “On-Farm Demonstration: Enabling Peer-to-Peer Learning.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 27 (5): 573–590. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2021.1959716.

- Taylor, Marcus, and Suhas Bhasme. 2018. “Model Farmers, Extension Networks and the Politics of Agricultural Knowledge Transfer.” Journal of Rural Studies 64 (November): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.09.015.

- Unay Gailhard, İlkay, Miroslava Bavorová, and Frauke Pirscher. 2015. “Adoption of Agri-Environmental Measures by Organic Farmers: The Role of Interpersonal Communication.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 21 (2): 127–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2014.913985.

- Van Poeck, Katrien, Jeppe Læssøe, and Thomas Block. 2017. “An Exploration of Sustainability Change Agents as Facilitators of Nonformal Learning: Mapping a Moving and Intertwined Landscape.” Ecology and Society 22 (2): art33. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09308-220233.

- Verhoog, Henk, Mirjam Matze, Edith Lammerts van Bueren, and Ton Baars. 2003. “The Role of the Concept of the Natural (Naturalness) in Organic Farming.” Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 16 (1): 29–49. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021714632012.

- Yin, Robert K. 2018. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods. 6th ed. Los Angeles London New Delhi Singapore Washington DC Melbourne: SAGE.