Abstract

Texture modified consistencies (TMC) is a common compensatory strategy in dysphagia management. Lack of consensus regarding TMC terminology places a person at risk of poor oral intake, malnutrition, dehydration, and aspiration.

Purpose

To investigate: (a) Swedish Speech-Language Pathologists (SLPs) dysphagia management with TMC, including terminology, inter-professional collaboration, and knowledge of standard TMC guides; and (b) the current TMC terminology/guides used within university hospitals, in Sweden.

Method

Part One surveyed SLPs from 19/21 regions. Recruitment occurred via regional SLP/department managers, the national SLP association and email lists. Non-parametric statistics were employed. Part Two explored TMC guides within the seven university hospitals.

Result

The initial survey identified 78 Swedish TMC terms. Overlap of both TMC terms and descriptions occurred. Different terms to describe same/similar textures were used by 70% of the SLPs. Knowledge of established guides was high (>90%), though TMC was often (60%) based on locally developed documents. Collaboration with other professions was reported by 97% of SLPs, however almost half perceived collaboration to be inadequate, citing difficulties with transfer of TMC recommendations. Variance in TMC terms/guides within/across the university hospitals occurred.

Conclusion

Variable TMC terminology is used in Sweden, impacting optimal dysphagia management. Future research should focus upon implementation of standardised TMC terminology.

Introduction

Swallowing difficulties can be a significant and debilitating symptom evidenced in both children and adults who acquire a range of medical diagnoses [Citation1–3]. The effects of dysphagia can be severe, including asphyxiation, malnutrition, dehydration, aspiration pneumonia and death [Citation4–6]. The negative consequences of dysphagia are not only physiological. Various studies have also shown negative impacts on numerous aspects of a person’s social and psychological well-being; significantly affecting quality-of-life [Citation7–9]. In healthcare settings, dysphagia is significantly associated with prolonged hospital lengths-of-stay, increased medical and total healthcare costs [Citation4,Citation5,Citation10–12]. Given the negative impacts of dysphagia, effective management is essential.

Dysphagia management often uses compensatory strategies and rehabilitation exercises to improve a person’s swallow safety and/or efficiency [Citation3,Citation13–15]. Texture modified consistencies (TMC), which refers to the modification of fluids and/or foods, is a common, perhaps controversially overused, compensatory technique [Citation16–20]. Regardless of the suggested negative consequences associated with TMC such as malnutrition, dehydration, sensory and palatability concerns, TMC remain the cornerstone of dysphagia management [Citation15,Citation21,Citation22].

Although there is a growing body of evidence for texture modification, several studies have also noted the diversity in terminology and lack of guidelines [Citation21–23]. These studies indicate a need for standardised terminology, descriptions, and testing-methods to better ensure patient care and safety. Furthermore, it has been reported that standardisation of terminology has the advantage of improving communication between healthcare professionals and preventing ambiguity and misunderstandings in dysphagia management [Citation21–23]. Guidelines implemented within other healthcare fields have also shown beneficial results [Citation24,Citation25]. Thus, over the past decades various countries have subsequently developed national TMC standards to address dysphagia management inconsistencies, including national guides in the UK, US, Japan, Australia, and Ireland to name a few [Citation23,Citation26].

Today, the field of texture modified fluids and foods have developed further, focusing not only on national, but international collaboration and consensus. The International Dysphagia Diet Standardisation Initiative (IDDSI) has since 2012 globally researched and developed an evidence-based guide providing terminology, descriptors, testing methods, and evidence for a range of different fluid and food levels [Citation21]. Addressing national and international guides’ lack of transference, the IDDSI project intends to be accessible regardless of profession, age, culture, or language [Citation21]. At the time of manuscript preparation, the IDDSI framework had been adopted and/or implemented in countries from most continents around the world and it had been translated, or was in the process of being translated, into over 30 languages [Citation27]. In-line with international standardisation trends, the European Society of Swallowing Disorders (ESSD) is also researching standard terminology and descriptors for modified fluids including standards for viscosity measurement, amylase resistance and thickening agent description [Citation15] .

It is well-established that standardisation of TMC is essential for patient safety and high-quality dysphagia management [Citation3,Citation13,Citation15,Citation22]. To move toward this, it is important for professional organisations and governments to review local and national practice and identify future areas for improvement. From a Swedish perspective, a texture modified food guide was first developed in 2007, in a research project funded by the Swedish innovation agency (Vinnova). This guide became informally known as the Findus Consistency Guide, and was a collaboration between Findus Special Foods, the Swedish National Board of Health & Welfare (Socialstyrelsen), the National Food Agency (Livsmedelverket), dietitians and SLPs, and was coordinated through the former Swedish Institute for Food and Biotechnology [Citation28]. The guide was created with a purpose to define different food textures and was based on the former British National TMC guide from 2002 [Citation28]. The Swedish guide (now known as The Consistency Guide) was further researched by Wendin et al. [Citation28] to quantify objective sensory descriptions and texture measurements for each of the food consistencies. Their study concluded that it was of importance to standardise terminology, recipes, and include objective definitions to ease communication between healthcare professionals and food producers. The absence of a guide and scale for fluids was addressed but not resolved, and The Consistency Guide deemed in need of further research to maintain validity. Currently, the use and acceptance of this, or other guides, in a clinical setting by SLPs in Sweden remains unknown. The general lack of clinical national guidelines for SLPs in Sweden, and its probable effect on care and practice, are mentioned in a survey study by Johansson et al. [Citation29] as well as by Möller et al. [Citation30].

In 2019, a national working party consisting of (10) SLPs and dietitians presented survey results (n = 187) at the annual dysphagia meeting, Malmö, Sweden [Citation31]. Data from this online survey explored TMC guides used by healthcare professionals and was answered by SLPs (47.6%), dietitians (41.7%), hospital chefs (5.9%) and “others” (4.8%). Results identified that there are different guides used throughout Sweden for modified fluids where: 47.1% use The Consistency Guide; 39% use locally developed guides; 28.9% use IDDSI; and 8.6% use “other”. For texture modified foods: 73.8% use The Consistency Guide; 26.2% use locally developed guides; 18.7% use IDDSI; and 5.3% use “other” [Citation31].

Given that the Swedish healthcare system is predominantly governed by regional or county councils and municipalities, which allow for extensive self-governing, wide variability in practice occurs. Therefore, it is probable that SLPs and other healthcare professionals (HCP) may work and collaborate differently and to different extents throughout the country, likely negatively impacting optimal dysphagia management. This research, which commenced in 2017, with further follow-up data collection in 2020–2021, aimed to investigate TMC terminology used in Sweden and summarise the current status across the seven Swedish university hospitals.

Part One of this research investigated:

The terminology used by Swedish SLPs to describe texture modified consistencies of fluid and food in patients with dysphagia.

If a difference in SLP dysphagia experience resulted in a significant difference in knowledge of research-developed guides/guidelines.

If the extent of collaboration with other HCP regarding terminology surrounding TMC was perceived to be mutual and adequate.

Part Two of this research explored which guide was currently used to describe texture modified consistencies for fluid and food at the seven university hospitals in Sweden.

Methods

Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Sahlgrenska Academy at the University of Gothenburg (GU) guidance for scientific research within undergraduate education and training (routine for ethical approval). No ethical approval was deemed necessary as per GU student research work since no data within this study is traceable to participants. For Part One of this research (national survey of SLPs), all participants provided informed consent prior to submitting their survey responses, no identifying participant information was requested nor obtained. Part Two of this research, exploring the current status of TMC terminology used at the university hospitals, obtained data via the SLP and Dietetics department via email and/or telephone. No identifying data is reported.

Part One: survey of Speech-Language Pathologists (SLPs) working with dysphagia

Participants

This national, observational, cross-sectional study targeted SLPs who had worked with dysphagia during the previous six months. This time frame was chosen to ensure that current dysphagia experienced SLPs were surveyed. Participants were asked to anonymously complete a study specific questionnaire online without interviewer support. This ensured that answers could be sampled from the target population whilst covering a large geographical area within a limited timeframe and with limited funding. Participation was voluntary and could be withdrawn at any time prior to survey submission. To ensure confidentiality and anonymity, an open Uniform Resource Locator (URL) was used for the survey invitation.

Total number of respondents were 93, of which 88 matched inclusion criteria. Five (excluded) participants answered the survey despite not meeting the criteria of working with dysphagia within the recent six months. SLPs from 19 of 21 regions/county councils in Sweden (90%) responded, with only two county councils not represented. Participants worked within various settings: 81% with adults, 8% with paediatrics, and 11% reported to work with both adults and paediatrics. A range of caseloads were represented including, but not limited to, working in a neurological caseload (64%), general medical/hospital caseload (36%), and/or Ear-Nose-Throat caseload (11%). Responses were collected in 2017. See Supplemental Online Material 1, for more in-depth participant information.

Survey Design

Since no previous questionnaire had been validated within this research area, a study specific questionnaire was developed using published guides and recommendations for survey design [Citation32]. The survey was constructed with a web-based survey tool, Webropol (https://webropol.se/), as recommended by GU for security reasons. Webropol software licence was provided by GU. Data was automatically saved on Webropol’s server after submission and accessed by the authors only.

Pilot testing

An expert panel of four SLPs with expertise within TMC and dysphagia, naïve to the survey, completed the first pilot testing as per questionnaire design recommendations [Citation32]. Following feedback, edits around wording, understandability of questions, and survey structure were then incorporated. A second pilot testing then occurred with half of the original expert panel. This did not result in alteration of questions nor formatting, however a comment section for general thoughts/comments at the end of the survey was added. Survey completion time was reported to be 15–20 min.

The final survey contained 22 questions with both forced-choice and free-text response formats. Questions were displayed on nine pages and grouped together by five thematic sub-sections; (1) Background, (2) Dysphagia, (3) Texture modification of fluids and foods, (4) Guides and guidelines, and (5) Collaboration. A copy of the survey questions (in Swedish and in English) can be downloaded as Supplemental Online Material 2.

For terminology, descriptive data was gathered in two parts: one covering fluid terminology and the other covering food terminology. For texture modified fluids and texture modified foods, both (a) terms, and (b) descriptors for the terms, were reported individually in separate boxes for each fluid/food – with one term per box. That is, respondents were instructed to (a) name the term, and (b) the description for that term, in order of the least modified to the most modified consistency.

Data collection

Cross-sectional data was collected using nonprobability sampling. Due to the lack of a national register of SLPs working with dysphagia in Sweden [Citation29], a snowball sampling methodology was used to recruit respondents [Citation32]. Department managers from the 21 county councils and hospitals who provided SLP services were emailed and asked to forward a study introductory letter including the URL to the online questionnaire. To increase sampling rate, the URL was also posted on Sweden’s national web forum for SLPs (Logopedforum) and advertised on relevant SLP Facebook websites. Reminders were sent by email and posted on Logopedforum and Facebook twice during the data collection period.

Part Two: current status of Texture Modified Consistency (TMC) use in Sweden

In 2020–2021, the use of TMC guides used in the seven university hospitals in Sweden was explored. As an adjunct to the national survey, two follow-up questions were sent to the dietitian and SLP departments at the university hospitals in Sweden, including (alphabetically) Karolinska University Hospital (Stockholm), Linköping University Hospital (Linköping), Sahlgrenska University Hospital (Göteborg), Skåne University Hospital (Malmö and Lund), University Hospital of Umeå (Umeå), Uppsala University Hospital (Uppsala), and Örebro University Hospital (Örebro). These questions asked:

Which guideline or system is used at your hospital to describe texture modified fluids for people with swallowing difficulties?

Which guideline or system is used at your hospital to describe texture modified foods for people with swallowing difficulties?

Data analysis

Terminology of texture modified consistencies

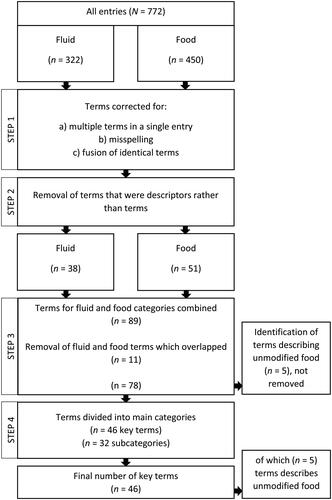

Descriptive data for TMC terms were reviewed and reported using a four-step summarising method by authors JYH and JL – see Flow Diagram, . First, raw data for all entries, (fluid n = 322, and food n = 450) underwent correction for: (a) multiple terms in a single entry (i.e. several different terms were supplied in the one data entry box); (b) misspelling; and (c) fusion of identical entries. Listed corrections were completed first for the fluid, then for the food category. Secondly, the data pertaining to terminology were then corrected for when descriptions were used rather than terms, i.e. entries that were not a stand-alone term, but instead a description of the modified fluid/food, were removed from the list. Thirdly, terms describing a non-modified food consistency, were identified. Categories of fluid and food were also compared for overlapping terms. The final step searched remaining terms for possible division into (a) key, stand-alone terms and (b) subcategories (terms with a descriptive adjective). For summary of the final 46 key TMC terms reported, see Supplemental Online Material 3.

Figure 1. Process of analysing reported terms for texture modified consistencies.

The effect of (1) dysphagia experience, and (2) frequency of working with dysphagia on participants’ knowledge of guides

Respondents provided information regarding their self-reported level of dysphagia experience, measured on a 5-point Likert scale (very little, little, neither little nor much, much, very much). Information regarding the SLPs frequency of working with dysphagia (as a percentage of their caseload, categorised into 0–19%, 20–39%, 40–59%, 60–79% and 80–100%) was also collated – see Supplemental Online Material 1. These data were then compared with their reported knowledge of research-developed guides: (a) no knowledge of listed guides; (b) knowledge of one listed guide; and (c) knowledge of more than one listed guide. Microsoft Excel and IBM SPSS version 24 (International Business Machines Statistical Package for Social Science) were used for statistical analysis.

Collaboration with other healthcare professionals (HCP)

Data from the initial survey, investigating collaboration with other HCP and perceived adequacy of TMC terminology, were descriptively analysed. Respondents’ free text answers and comments were reviewed by authors JYH and JL, with analysis based on inductive content analysis [Citation33]. Material was repeatedly reviewed, and codes identified which manifested one statement or idea from within the text. Codes were clustered then combined into categories to create the main ideas and suggested summarisation.

Current status of texture modified consistency use in Sweden

Part Two of this research, using two follow-up questions, investigated the current TMC terminology and guides used at the seven university hospitals in Sweden. Data were descriptively analysed.

Results

Terminology used by Speech-Language Pathologists to describe texture modified consistencies

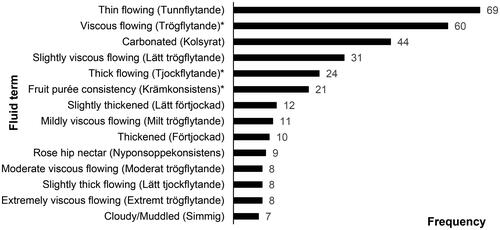

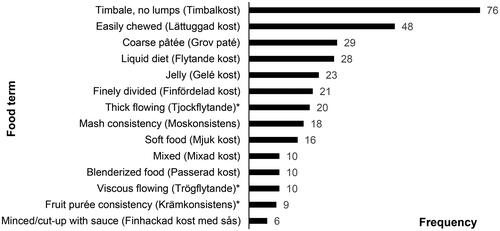

Data shows that a total of 78 different fluid and food terms were used by SLPs in their dysphagia management - see and . For fluids, a total of 38 different terms were reported. For food, 51 different terms were identified. Five of the food terms were non-modified consistencies. An overlap of 11 identical terms for fluid and food were reported. Stand-alone key-terms for fluid and food resulted in a combined total of 46 terms. A summary of key-terms and subcategories can be found in Supplemental Online Material 3.

Figure 2. Terminology used by speech-language pathologists when describing modified fluids. English translation followed by Swedish terminology in brackets. All terminology with ≥5 answers are represented. Twenty-five terms with < 5 entries were not included in figure. Terms marked with an asterisk* are overlapping for both fluid and food.

Figure 3. Terminology used by speech-language pathologists when describing texture modified food consistencies. English translation followed by Swedish terminology in brackets. All terminology with ≥5 answers are represented. Thirty-one terms with < 5 entries and unmodified food consistencies were not included in figure. Terms marked with an asterisk* are overlapping for both fluid and food.

Respondents’ associated descriptions of the listed terms resulted in a large data set that is not presented in the current study (See Supplemental Online Material 3 and 4 for summary). Of note, was the overlap between numerous terms and descriptions found within the raw data (not presented). For example, rose-hip nectar was a commonly used consistency key-term yet also used as a description. When asked if the SLPs ever used different terms to describe the same or similar consistency, 70.1% (n = 61) answered yes, 17.2% (n = 15) answered no and the rest 12.6% (n = 11) reported unsure/don’t know. Respondents used between 2-8 boxes for fluid (M = 3.7, Md = 4) and 2–11 boxes for food (M = 5.1, Md = 5), indicating that a wide range of terminology descriptions are in use in Sweden for both fluid and food TMC. Summarised key-terms and their descriptions/subcategories in Swedish can be found in Supplemental Online Material 4.

Respondents reported that the 78 TMC terms were derived from the following sources: Documents created for the specific workplace, 59.1% (n = 52); The (Findus) Consistency Guide, 34.1% (n = 30); Documents created for the specific region, 29.5% (n = 26); Not sure, 19.3% (n = 17); IDDSI Framework, 18.2% (n = 16); Clinical guidelines from the Swedish Association of Speech-Language Pathology, 5.7% (n = 5); Other countries’ national guidelines, 4.5% (n = 4); Documents from National Board of Health & Welfare, 3.4% (n = 3); and Other, 8.0% (n = 7), including TMCs obtained through training, from the hospital kitchen, the consistency hierarchy, and through verbal agreement with colleagues.

The effect of SLPs’ dysphagia experience on their knowledge of guides

identifies that there was no difference between SLPs level of dysphagia experience nor their frequency of working with dysphagia, and how many researched-developed TMC guides they knew. Descriptive statistics showed that 54.5% of respondents (n = 48) had knowledge of more than one research-developed guide or guideline, with 36.4% (n = 32) reporting to have knowledge of only one. Nine percent (n = 8) indicated no knowledge of any guidelines. In terms of guidelines: 78.4% (n = 69) had knowledge of The Consistency Guide; 55.7% (n = 49) of IDDSI framework; and 13.6% (n = 12) of the Australian Standards for Texture Modified Foods and Fluids.

Table 1. The effect of dysphagia experience on participants’ knowledge of research-developed guides.

Speech-language pathologists’ collaboration with other healthcare professionals

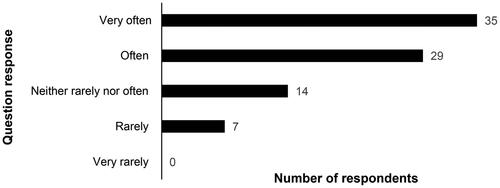

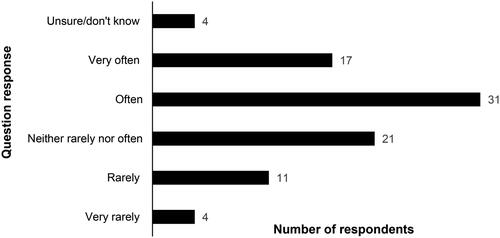

Of respondents, 96.6% (n = 85) of SLPs reported to collaborate with other HCPs, and 3.4% (n = 3) reported not to. Interprofessional collaboration is detailed in . Perceived extent of collaboration when working with TMC in patients with dysphagia is reported in . Most SLPs (55%, n = 48) reported that the mutual use of TMC terminology by other HCP occurred often/very often, see .

Figure 4. Speech-language pathologists’ experience of collaboration with other healthcare professionals when working with texture modified fluid and food in patients with dysphagia.

Figure 5. Speech-language pathologists’ opinion regarding to what extent the terminology used is also mutual with other healthcare professionals when working with texture modified fluid and food in patients with dysphagia.

Table 2. Speech-language pathologists’ reported collaboration with other healthcare professionals.

Open-ended comment sections

Respondents’ comments were derived from the four open-ended sections: Fluid (n = 35); Food (n = 27); Guidelines (n = 18); and General (n = 32). Several sections had common or related themes such as: (a) factors affecting a consensus on terminology/practice; (b) implementation challenges; with (c) comments identifying that current terminology is based on either local documents, The Consistency Guide or IDDSI. Since completion of Part One of this study, IDDSI has now been translated into Swedish [Citation38]. For a complete overview of categories and examples of open-ended comments, see .

Table 3. Categories and examples of open-ended comments with number of comments connected to each category shown in brackets.

Current status of texture modified consistency use in Sweden

The two follow-up questions investigating current TMC terminology and guides used at the seven university hospitals in Sweden were descriptively analysed, see . Only two university hospitals reported internal consensus between the dietitian and SLP departments on terminology. Four hospitals used or were in the process of implementing IDDSI. In most cases, there was uncertain use of terminology, or terminology variability reported between SLP and dietitian departments, even within the same university hospital.

Table 4. Answers from dietetic and Speech-Language Pathology (SLP) Departments from Seven University Hospitals in Swedena regarding use of guide or guideline for describing texture modified fluid and food for patients with swallowing difficulties.

Discussion

Part One of this research, surveyed SLP terminology and practice within the field of TMC use for patients with dysphagia. Results revealed a wide variety of terms used (n = 78), an overlap between terminology for fluid and food, different terms describing the same consistencies, and an uncertainty of the sources for terminology in current use. The SLP participants expressed difficulties conveying TMC – stemming from external environmental factors such as kitchen resources, other HCPs’ practice and their mutual understanding of TMC terminology – all of which negatively impact dysphagia management [Citation23,Citation34]. Knowledge of research-based guides was high, however this did not have any extensive effect or carry-over to the terminology used in practice. Results are also consistent with previous research which indicate that without well implemented guides containing consensus on terminology among all relevant stakeholders, variability and inconsistency ensues [Citation23,Citation28,Citation35,Citation36].

The authors agree with previous research reporting possible negative consequences for dysphagia practice, which were also mentioned in comments given by respondents. Negative consequences reported in Part One of this research included, but are not limited to, a negative impact on accuracy, efficacy, patient safety and also the ability to perform good quality research [Citation23]. According to Wendin et al., reaching a consensus for terminology when prescribing TMC in Sweden was an important future direction to prevent variable and suboptimal dysphagia management [Citation28]. Results from Part Two of the current study, from the seven university hospitals (2020–2021), continue to identify variable TMC terminology use in Sweden.

In terms of TMC variability, results from Part One of this research identified that reported terms for TMC were numerous, ambiguous, and often difficult to separate from a term’s connected description, with a frequent overlap between key-terms and their descriptions. Respondents could, for example, give the TMC term pudding and then describe it as “like pudding”. A common description for different types of thickened fluid was rose-hip nectar – also reported as a key-term by other respondents. These overlaps occurred within data for individuals as well as between different respondents. Such overlaps between terms and descriptions negatively influences dysphagia management, as indicated by previous research highlighting the pitfalls of when TMC is insufficient, inconsistent, and not optimally transferrable [Citation23,Citation28].

Many TMC terms related to a specific type of food, something that may help describe it, but does not always ensure reliability nor mutual understanding, i.e. a specific term used may be different depending on food brand and individual perception [Citation22]. An example of this is the reported use of buttermilk or rose-hip nectar, which can flow differently depending on brand and temperature, or porridge, which can be created with different ingredients and cooked to varying thickness. Other terms with an extensive interpretational range included the many fluid terms (and their variations) of thin, thick, and viscous descriptions. All these share the common denominator of being difficult to describe and/or replicate without additional descriptions or recipes (see Supplemental Online Material 3 and 4). As such they can be interpreted differently by SLPs, HCPs, patients, and caregivers – jeopardising patient safety and treatment efficacy as highlighted in previous literature [Citation23,Citation35,Citation37].

To further complicate TMC communication and patient safety, not only did SLPs report a variety of TMC terms and descriptions, but other collaborating HCPs were also frequently not using the same terminology when working with TMC. Results from Part One of this research demonstrated that 40 SLPs (45.5%) self-reported that they very rarely, neither rarely nor often, or were unsure of if mutually understandable terminology was used with other HCPs (). Results from the open-ended comments also highlighted difficulties in transferring recommendations and ensuring collaborative practice – all concerning factors for dysphagia management, increasing the risk of miscommunication between HCPs, SLPs and patients. In Part Two of this research, exploring TMC terminology at the seven university hospitals, variability was noted between the SLP and dietetics department at most of the university hospitals.

Ineffective communication is known to result in negative consequences [Citation34]. Results from Part One of this research indicate that a consensus on terminology should be prioritised with the aim to positively impact collaboration whilst, importantly, improving communication transfer between SLPs, other HCPs and patients, as well as across hospitals within the same region. These goals for optimal dysphagia management are further supported by research evaluating the uptake of the Australian standardised terminology and definitions for TMC and similar work by the International Dysphagia Diet Standardization Initiative [Citation21–23,Citation35]. Part Two of this research indicates such trends of improving TMC standardisation in Sweden, with four of seven university hospitals in the process of moving towards IDDSI use or implementation.

This trend towards improved standardisation of TMC is noteworthy, particularly since it appears that the TMC field is rapidly changing in Sweden. In the period between Part One and Part Two of this research, IDDSI had been scientifically translated into Swedish and made available on the iddsi.org website. Data from the National Dysphagia Network meeting in 2019 [Citation31] and Part Two of this research from the seven university hospitals in Sweden (2020–2021) indicate a growing adoption of IDDSI. The IDDSI framework provides evidence-based TMC terms, descriptions, and standardised testing methods, and is being used as the standard descriptor for TMC in dysphagia research internationally [Citation21–23]. Furthermore, the IDDSI website and network provides resources to assist in adoption and implementation. Implementation, however, requires more than just resources.

Implementation research shows that personal factors, such as knowledge of a guideline alone, is insufficient to make successful changes in practice, even if evidence based [Citation36]. This again echoes the results from Part One of the current study which identified that knowledge of guides for texture modified consistencies were high among respondents, with almost every SLP knowing at least one. Yet, despite a reported high knowledge of guides, this did not impact the respondents’ reported practice. The majority of respondents based TMC guides on locally created (59%) or regionally developed documents (30%), and many reported sources of their TMC to be unknown (19%). Although the translation and cultural adaptation of IDDSI [Citation38]has occurred since the initial study (Part One) was conducted, Part Two of this study (conducted almost four years after the initial survey), demonstrates the continuing variability in TMC use across Sweden. This knowledge – usage gap could be explained by the fact that even if knowledge of terminology from a standardised international (and translated) guide exists, it is unlikely to improve communication or ease practice without local and national implementation [Citation23,Citation28].

Regarding optimal dysphagia management, Swedish HCPs are bound by law to work according to evidence-based practice and to maintain high patient safety standards as per the Patient Safety Act (2010:659) [Citation39]. This research identifies areas for improvement within dysphagia management specifically in terms of TMC terminology and mutual understanding for: (a) improved communication between HCP, key stakeholders, patients and family; and (b) not least, improved patient safety. The importance of mutual terminology for efficient communication is further underlined in current research, emphasising collaboration in multidisciplinary teams around patients with dysphagia [Citation11]. Future changes to the healthcare system would thus benefit from focusing on all relevant healthcare, professional organisations and key stakeholders, including, but not limited to: National Associations of Dietitians, Speech Pathology; the National Board of Health & Welfare; the National Food Agency; nutrition companies; food producers, healthcare support services, such as kitchen staff; and other clinical HCPs. Other important key stakeholders to include are patient support and voluntary organisations, particularly considering communication resources for patients and their families [Citation23].

According to Swedish resources from the National Board of Health & Welfare, implementation in healthcare is achieved by managing three areas; the users (education and guidance), the organisation (readiness for change, resources, feedback) and the leadership (managing sudden, unforeseen events and motivating professionals) [Citation40]. Although these three areas of implementation were not primarily investigated in this study, results on SLPs’ knowledge of guides, together with comments in the open-ended sections, clearly reflect issues with change and implementation. SLPs expressed that their practice was restricted due to work environment related factors. Examples of this were hospital kitchens with limited textures to offer, not being able to change terminology due to the practice of other HCPs, or uncertainty of other HCPs understanding the terminology used. Hence, before implementing any new guide and standardised terminology, further research and planning would be required if nationwide uptake is to be achieved [Citation35,Citation36]. This is identified and addressed within international dysphagia terminology and implementation research where resources and implementation framework and guides support the three areas of (a) promoting awareness, (b) preparing for change, and (c) adoption of the International Dysphagia Diet Standardisation Initiative [Citation27].

Limitations

As with all research, this study has its limitations. Part One of this study used non-probability sampling and open invitations to distribute the survey. This therefore influences the ability to calculate for response and non-response rate, which is required to estimate whether survey results are representative and generalisable to the greater population [Citation32]. Since the current study targeted SLPs working in healthcare, respondents’ answers in this study are expected to be somewhat representative of SLPs matching inclusion criteria. An exception to this, however, are SLPs working with dysphagia in paediatrics and the habilitation caseloads, as respondents in the current study reported to work mostly with adults.

Regarding the study sample size for Part One, previous studies have similarly struggled to reach SLPs within specific sub-groups [Citation29]. Although snowballing is commonly used to contact hard-to-reach populations, this method potentially risks the sample becoming more representative of one area whilst failing to reach others [Citation32], a limitation demonstrated in the current study. Nevertheless, a strength of the current study was that this survey, geographically, collected responses from all but two regions in Sweden, consequently making data broadly representative nationally, even if few respondents were recruited within some areas. True representativeness in studies of the Swedish SLP population is otherwise impossible to calculate since no public data exists with detailed information regarding number of SLPs working with dysphagia, nor SLP dysphagia caseloads across different workplaces.

Part Two of the current study posed the question, “Which guideline or system is used at your hospital to describe texture modified fluids/foods for people with swallowing difficulties?”. This infers that a guide/system is expected and may forge a biased response. Other, non-leading questioning may therefore have resulted in different responses.

Finally, whilst this research was being undertaken, the adoption of IDDSI across Sweden was increasing. Part One of this study was conducted in 2017 and IDDSI had not yet been translated into Swedish. The IDDSI framework was scientifically translated and published on the international website, iddsi.org, in January 2021. In hindsight, it is possible that the availability of IDDSI, in Swedish, could have affected results from Part One of the current research. Further research regarding this may be warranted.

Conclusion

Results from this national survey (Part One of this research) showed that Swedish SLPs in 2017 used a wide variation of terminology that was reportedly hard to replicate and transfer information between and within HCPs and patients, potentially affecting both patient safety and interprofessional work efficiency. Reports from the seven university hospitals in Sweden in 2020–2021 (Part Two of this research), continue to identify variable TMC terminology use. Although most SLPs (91%) were aware of at least one research-based guide, use of local/regional terminology continued (60%). Results from this study indicate that collaboration between HCPs within dysphagia management is high however communication regarding TMC between the various health professions is inadequate. Only half of the SLPs surveyed (55%) reported that mutual terminology used with other HCP occurred often/very often. Suboptimal management of dysphagia, including miscommunication and errors with TMC, is an established patient safety risk and requires a concerted effort for improvement. The authors of this study conclude that with well-researched international resources available regarding TMC terminology, testing-methods and guides, future research should focus on the necessary steps to implement international standardised terminology for improved dysphagia management.

SOM_4_terminology_in_Swedish.docx

Download MS Word (20.4 KB)SOM_3_terminology_in_English.docx

Download MS Word (19.7 KB)SOM_2_survey_questions.docx

Download MS Word (33.3 KB)SOM_1_respondent_information.docx

Download MS Word (19.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Dodrill P, Gosa MM. Pediatric dysphagia: physiology, assessment, and management. Ann Nutr Metab. 2015;66 (Suppl 5):24–31.

- Morgan AT, Dodrill P, Ward EC. Interventions for oropharyngeal dysphagia in children with neurological impairment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:Cd009456.

- Wirth R, Dziewas R, Beck AM, et al. Oropharyngeal dysphagia in older persons - from pathophysiology to adequate intervention: a review and summary of an international expert meeting. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:189–208.

- Altman KW, Yu GP, Schaefer SD. Consequence of dysphagia in the hospitalized patient: impact on prognosis and hospital resources. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;136(8):784–789.

- Arnold M, Liesirova K, Broeg-Morvay A, et al. Dysphagia in acute stroke: incidence, burden and impact on clinical outcome. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(2):e0148424.

- Lanspa MJ, Jones BE, Brown SM, et al. Mortality, morbidity, and disease severity of patients with aspiration pneumonia. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(2):83–90.

- Ekberg O, Hamdy S, Woisard V, et al. Social and psychological burden of dysphagia: its impact on diagnosis and treatment. Dysphagia. 2002;17(2):139–146.

- Leow LP, Huckabee ML, Anderson T, et al. The impact of dysphagia on quality of life in ageing and Parkinson’s disease as measured by the swallowing quality of life (SWAL-QOL) questionnaire. Dysphagia. 2010;25(3):216–220.

- Martino R, Beaton D, Diamant NE. Perceptions of psychological issues related to dysphagia differ in acute and chronic patients. Dysphagia. 2010;25(1):26–34.

- Attrill S, White S, Murray J, et al. Impact of oropharyngeal dysphagia on healthcare cost and length of stay in hospital: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):594.

- Dziewas R, Beck AM, Clave P, et al. Recognizing the importance of dysphagia: stumbling blocks and stepping stones in the twenty-first century. Dysphagia. 2017;32(1):78–82.

- Muehlemann N, Jouaneton B, de Léotoing L, et al. Hospital costs impact of post ischemic stroke dysphagia: database analyses of hospital discharges in France and Switzerland. PLoS One. 2019;14(1):e0210313.

- Gosa MM, Dodrill P, Robbins J. Frontline interventions: considerations for modifying fluids and foods for management of feeding and swallowing disorders across the life span. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2020;29(2s):934–944.

- Lazarus CL. History of the use and impact of compensatory strategies in management of swallowing disorders. Dysphagia. 2017;32(1):3–10.

- Newman R, Vilardell N, Clavé P, et al. Effect of bolus viscosity on the safety and efficacy of swallowing and the kinematics of the swallow response in patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia: white paper by the European Society for Swallowing Disorders (ESSD). Dysphagia. 2016;31(2):232–249.

- Murray J, Miller M, Doeltgen S, et al. Intake of thickened liquids by hospitalized adults with dysphagia after stroke. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2014;16(5):486–494.

- Okkels SL, Saxosen M, Bügel S, et al. Acceptance of texture-modified in-between-meals among old adults with dysphagia. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2018;25:126–132.

- Shimizu A, Maeda K, Tanaka K, et al. Texture-modified diets are associated with decreased muscle mass in older adults admitted to a rehabilitation ward. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2018;18(5):698–704.

- Vucea V, Keller HH, Morrison JM, et al. Modified texture food use is associated with malnutrition in long term care: an analysis of making the most of mealtimes (M3) project. J Nutr Health Aging. 2018;22(8):916–922.

- Beck AM, Kjaersgaard A, Hansen T, et al. Systematic review and evidence based recommendations on texture modified foods and thickened liquids for adults (above 17 years) with oropharyngeal dysphagia - an updated clinical guideline. Clin Nutr. 2018;37(6 Pt A):1980–1991.

- Cichero JA, Lam P, Steele CM, et al. Development of international terminology and definitions for texture-modified foods and thickened fluids used in dysphagia management: the IDDSI framework. Dysphagia. 2017;32(2):293–314.

- Steele CM, Alsanei WA, Ayanikalath S, et al. The influence of food texture and liquid consistency modification on swallowing physiology and function: a systematic review. Dysphagia. 2015;30(1):2–26.

- Cichero JA, Steele C, Duivestein J, et al. The need for international terminology and definitions for texture-modified foods and thickened liquids used in dysphagia management: foundations of a global initiative. Curr Phys Med Rehabil Rep. 2013;1(4):280–291.

- Ormseth CH, Sheth KN, Saver JL, et al. The American Heart Association’s Get with the Guidelines (GWTG)-stroke development and impact on stroke care. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2017;2(2):94–105.

- Tassy L, Zrounba P, Girodet D, et al. Impact of clinical practice guideline’s on medical practice and survival for head and neck cancer management in first line treatment (N = 1121 patients). Ann Oncol. 2014;25:341

- Cichero JA, Heaton S, Bassett L. Triaging dysphagia: nurse screening for dysphagia in an acute hospital. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18(11):1649–1659.

- IDDSI. International dysphagia diet standardisation initiative: international dysphagia diet standardisation initiative; [cited 2021 Jan 30]. Available from: https://iddsi.org/Translations

- Wendin K, Ekman S, Bülow M, et al. Objective and quantitative definitions of modified food textures based on sensory and rheological methodology. Food Nutr Res. 2010;54(1):5134. 10.3402/fnr.v54i0.5134.

- Johansson MB, Carlsson M, Sonnander K. Working with families of persons with aphasia: a survey of Swedish speech and language pathologists. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(1):51–62.

- Möller R, Safa S, Östberg P. Validation of the Swedish translation of eating assessment tool (S-EAT-10). Acta Otolaryngol. 2016;136(7):749–753.

- McGreevy J, Dernbrant Y, Johansson J, et al. The Consistency Working Group. Presentation at the National Dysphagia Network Meeting; 2019; Malmö, Sweden.

- Kelley K, Clark B, Brown V, et al. Good practice in the conduct and reporting of survey research. Int J Qual Health Care. 2003;15(3):261–266.

- Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288.

- Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacum D. The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13 Suppl 1:i85–i90.

- Jukes S, Cichero JAY, Haines T, et al. Evaluation of the uptake of the Australian standardized terminology and definitions for texture modified foods and fluids. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2012;14(3):214–225.

- Shea CM, Jacobs SR, Esserman DA, et al. Organizational readiness for implementing change: a psychometric assessment of a new measure. Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):7. 2014/01/10

- Hanson B. A review of diet standardization and bolus rheology in the management of dysphagia. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;24(3):183–190.

- Dahlström S, Henning I, McGreevy J, et al. How Valid and Reliable Is the International Dysphagia Diet Standardisation Initiative (IDDSI) When Translated into Another Language?. Dysphagia. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-022-10498-2.

- Patient Safety Act (Patientsäkerhetslag [2010:659]). Ministry of Health and Social Affairs; 2010.

- Socialstyrelsen. Om implementering. [cited 2022 Feb 23]. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/ovrigt/2012-6-12.pdf