Abstract

Objectives. To identify patients at risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD) by analysis of clinical history. Design. A retrospective study of the Swedish cohort of 15–35 year olds having suffered an SCD during 1992–1999 and having undergone a forensic autopsy (162 individuals). We sought information in forensic, police and medical records and from interviews with family members. Results. Syncope/presyncope, chest pain, palpitations or dyspnoea were present in 92/162, unspecific symptoms such as fatigue, influenza, headache or nightmares in 35/162. Syncope/presyncope was most common (42/162). In 74 seeking medical attention, 32 had an ECG recorded (24 pathological). In 26 subjects there was a family history of SCD. Conclusions. The patient seeking medical advice before suffering an SCD is characterized by one to three of the following: 1) cardiac-related symptoms or non-specific symptoms often after an infectious disease, 2) a pathological ECG, 3) a family history of SCD. In 6 out of 10 a cardiac diagnosis was not considered. We conclude that symptoms preceding SCD were common but often misinterpreted.

Introduction

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) in the young is a shocking event as it strikes apparently healthy men and women, often without obvious warning signals. It is defined as a witnessed, natural, unexpected death from cardiac reasons occurring within 1 h after onset of symptoms in a previously healthy person, or an unwitnessed natural unexpected death of a person observed to be well within 24 h of being found dead Citation1.

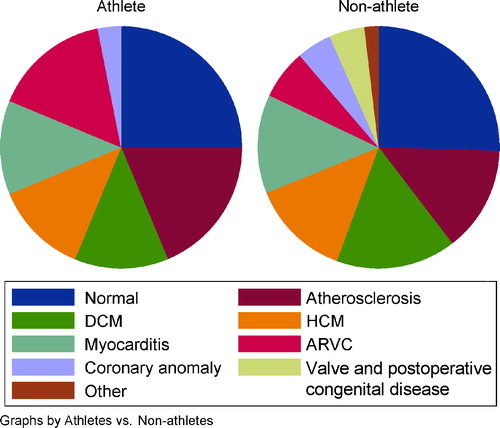

We have previously published two reports from the Swedish SCD cohort of 15–35 year olds 1992–1999 and found a stable incidence of about 1 per 100 000 per year, 73% men and 27% women Citation2. There were major or minor ECG abnormalities in 82% of the subjects with traceable ECGs, ST-T changes being most common Citation3.

Attempts to identify symptoms that are specific in patients at risk of SCD have not yet been successful. Previous studies have most often analysed the general population (all ages) where up to 80% of the individuals who suffer SCD have coronary heart disease. Fatigue has been one particularly common symptom, but is non-specific and found in many other conditions Citation4. In this paper we report a study of ante-mortem signs and symptoms in the Swedish SCD cohort of 15–35 year olds in Sweden 1992–1999, and try to link symptoms to each specific diagnosis.

Material and methods

We used all cases of SCD in 15–35 years olds in Sweden during the period 1992–1999, registered in the national Swedish database of forensic medicine (162 individuals with the exclusion of 19 cases with aortic aneurysm) Citation2. We searched for clinical details in forensic, police and medical records and obtained information from interviews with relatives by a questionnaire and by telephone interview.

Questionnaire and interview

For each subject, an informant (in most cases a close relative) was identified, either by the police report, the forensic institute or the population registry. Those who declined to participate were asked to indicate another informant. To those who accepted to participate, we sent a questionnaire containing 84 items related to the following domains:

relationship with the deceased

medical information (diseases, allergy, symptoms, medication)

family history

physical activity (frequency of training, participation in competitive sports)

food habits

stimulants used (alcohol, smoking and snuff use).

Main symptoms

The symptoms syncope/presyncope, palpitations, chest pain and dyspnoea were counted irrespective of when in the individual's life they occurred, but symptoms of infection and/or fatigue only if they were experienced within 2 months prior to death. If more than one symptom was reported, one of them was designated as the main symptom. In cases with syncope/presyncope this symptom was considered the main symptom. In other cases the main symptom was, in order of specificity: palpitations, chest pain, dyspnoea, fatigue/weakness, infectious disease, or in order of seriousness.

Statistical analysis

For comparison between groups the χ2-test was used. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

The regional ethics committee approved the study, and interviewed family members had given their informed consent.

Results

Data retrieval

Forensic pathology reports were available for all 162 individuals (115 men and 47 women), and 156 of those included a police report. Medical records were retrieved from 44 individuals (27%). One of the authors (A.W.) interviewed the relatives of 128 SCD victims (79%) who accepted to participate. In 10 cases no informant could be located, 13 did not respond and 11 individuals declined participation.

Main symptoms in relation to forensic diagnoses ()

Syncope (36 individuals) or presyncope (6 individuals), together 26% of the study group, were the most frequent symptoms in the SCD group. In a few cases there were also other concomitant symptoms such as sweating, headache, nightmares or nausea.

Table I. Family history and main symptoms in 162 cases of sudden cardiac death, by forensic diagnosis. Numbers in parentheses denote the number who consulted a doctor.

Syncope/presyncope ( and )

Syncope occurred between 6 h and 6 years prior to death. In six individuals, syncope appeared some weeks after an infectious disease (autopsy showed three cases each of myocarditis and normal heart). In 15 out of 31 cases who sought medical advice an ECG was taken. Two athletes died before a final diagnosis was made (both myocarditis). One man had been cardioverted because of ventricular tachycardia 2 years before death, but was later declared cardially healthy [autopsy showed arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC)]. One man, after extensive investigation, was suspected of having ARVC (which was the autopsy diagnosis). One case of long QT syndrome and one case of Wolff–Parkinson–White (WPW) syndrome were diagnosed and treated more than 10 years ante mortem.

Table II. Clinical characteristics in 42 patients with presyncope/syncope.

Chest pain ()

Chest pain preceded death by 0 h to 2 years. One subject was diagnosed with myocardial infarction 3 years prior to death, another was under investigation for chest pain. One man died in the car on his way to hospital and another man died just after arrival at the local medical centre. Clinical diagnoses used in cases with chest pain were anxiety Citation1, chest pain Citation1, musculo-skeletal pain Citation4, gastric ulcer Citation1, and four had no diagnosis.

Palpitations ()

In 20 individuals (12%) palpitations preceded death by 0 h to 9 months. One man aged 20 complained of palpitations during military training and died during exercise (autopsy showed a structurally normal heart). Eight out of 17 seeking medical advice underwent cardiac evaluation. Two athletes were considered as cardially healthy with no restrictions, abnormalities explained as typical of “athlete's heart” [autopsy showed ARVC and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), respectively]. Three cases of diagnosed HCM were given a beta-blocking agent. Other clinical diagnoses were supraventricular arrhythmia Citation1, pre-excitation Citation2, hypertension Citation2, allergy Citation1, anxiety Citation1, no diagnosis Citation5; none of these patients were under medical treatment or supervision.

Dyspnoea ()

Dyspnoea was an uncommon main symptom, but sometimes occurred together with syncope or palpitations. One subject was ante-mortem diagnosed with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), another cardially investigated without a diagnosis.

Fatigue, infection ()

Fatigue was reported in one-third of the SCD group, mainly as a coexisting symptom, and was thus seen in almost 50% of the patients with HCM and DCM, mainly together with syncope/presyncope or chest pain. Upper respiratory tract infections were seen in 11 cases and gastroenteritis in two cases. No cardiac evaluation was done in patients with infectious disease.

Distribution of main symptoms by age group

Chest pain was significantly more common in persons ≥30 years (18/60 ≥ 30 years vs 6/102 < 30 years, p<0.001). Syncope/presyncope was more common in the age group < 30 years (35 vs 7, p=0.002). Otherwise there were no significant differences between the age groups.

Activity at the time of death ()

Death was unwitnessed in 43% of the cases but in most a judgement of the activity at death could be arrived at. Death during ordinary daily activities was common in most diagnostic groups. However, in ARVC most died during physical activity (67%), and in subjects with a structurally normal heart most died during sleep.

Table III. Activity at death in 162 patients who suffered a sudden cardiac death, by diagnosis.

Distribution of main symptoms by sex ()

The total prevalence of possibly cardiac-related symptoms was higher in men 70/115 (61%) than in women 22/47 (47%), but this sex difference was not statistically significant. Palpitations were significantly more frequent in men (18 men vs 2 women, p<0.005). Twenty men and four women had chest pain (p=0.15). Infections were more common in women than in men (5 men, 8 women, p<0.007).

Ante-mortem investigation

In the total study group 74 (46%) sought medical advice because of symptoms, half of these within 6 months before death, one-third more than a year prior to death.

Of all 12-lead electrocardiograms taken in those seeking medical advice [32/74 (43%)], 24 (75%) were pathological, mostly with abnormal repolarization Citation3. In 23 of these cases at least one more cardiological investigation (e.g. echocardiogram, Holter monitoring, exercise testing) was done, resulting in eight cardiac diagnoses [HCM Citation3, one case each of long QT syndrome, ARVC, DCM, WPW syndrome, myocardial infarction]. In seven cases the diagnoses were settled more than a year before death, in one case 2 months before death (HCM). All eight were under treatment and supervision. None had an intracardiac defibrillator (ICD). In six individuals congenital heart disease was diagnosed in childhood, and four of these had been surgically treated.

Family history ()

There was heredity of SCD or a condition that could lead to SCD in first-degree relatives (brothers and sisters, children or parents) in 26 (16%) of the afflicted. A young man of 20 years with autopsy diagnosis ARVC had five relatives (all men; maternal grandfather and his brothers) who had suffered SCD. A young man aged 15 with autopsy diagnosis DCM had a sister who had died 7 years previously at the age of 7 (autopsy showed myocarditis). Long QT syndrome ante-mortem diagnosed in a woman was also present in her father, son and brother. Two siblings without ante-mortem diagnoses were included in our study; the man had DCM (ECG showed a short QT syndrome), the sister had normal heart at autopsy (no ECG). In four families, one first-degree relative now has an ICD implanted. No genetic analysis has been performed in the affected families to our knowledge.

Discussion

We believe this is one of the largest studies of signs and symptoms preceding SCD in 15–35 year olds. Systematic investigations in this group are difficult to perform because of low patient numbers. We saw a high frequency of cardiac-related symptoms and a certain pattern: syncope/presyncope being the most common symptom in the large diagnostic groups except in HCM and atherosclerosis, in which palpitations and chest pain was most common.

Comparison with other studies

Pooled data on 469 sudden deaths in young persons from nine studies show that the frequency of reported prodromal symptoms among young persons who die suddenly from cardiac causes is generally about 50% Citation5. Drory et al. reported prodromal symptoms in 52% of those with CAD, 35% in myocarditis and in 60% of cases with HCM, which is in good agreement with our results. The most frequent symptom was chest pain in subjects aged ≥20 years, and dizziness in those aged <20. Syncope was a rare symptom Citation6. However, other studies, like ours, found syncope/presyncope to be a common symptom prior to sudden death Citation7, Citation8.

Structurally normal heart

Syncope/presyncope was the most common symptom in cases with no detectable pathology in the heart at forensic autopsy. This was the largest diagnostic group in the Swedish cohort constituting one-fifth of the cases Citation2. Death during sleep was the most common mode of death in these patients, two-thirds of them being men. Death during sleep is known to be common in Brugada syndrome, sometimes called “sudden unexpected nocturnal death syndrome” Citation9. Other disorders which may lead to an SCD with no or limited autopsy findings include myocarditis with subtle changes, long and short QT syndrome and catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Only in one case of a structurally normal heart was an ante-mortem diagnosis established (long QT syndrome). Recent studies have shown that non-structural heart diseases causing arrhythmias are mostly a consequence of ion channel gene mutations. Therefore, genetic testing of affected families may be a possibility in the future Citation10.

Structural cardiac disease

In structural cardiac diseases symptoms develop gradually which makes the majority of patients asymptomatic or only mildly symptomatic Citation1. However, structural heart disease is a major risk factor for sudden death in patients with syncope Citation11–13. This was, in part, confirmed by our study, syncope being the most common symptom in all cardiomyopathies except in HCM. The combination of syncope and palpitations was common in our patients with ARVC. These are typical clinical features earlier reported in ARVC as well as a 7–23% risk of SCD Citation14, Citation15. The high frequency of palpitations reported in our group of HCM patients suggests that this is a potentially ominous symptom preceding SCD. Cardiac arrest may be triggered by arrhythmias, and studies have shown that non-sustained ventricular tachycardia is a useful marker of increased risk of SCD in patients with HCM Citation16,17. In the literature dyspnoea is reported in up to 90% of symptomatic patients with HCM, and the combination of young age, syncope at diagnosis, severe dyspnoea and a family history of sudden death best predicted the sudden death Citation11. In myocarditis we saw not only non-specific symptoms, such as fatigue and precordial discomfort often reported in the literature Citation1, but also specific symptoms such as syncope/presyncope often following an influenza-like illness.

Symptoms often misinterpreted

Distinct symptoms such as syncope, chest pain or palpitations may arouse the suspicion of cardiac disease while febrile disease or fatigue will probably not. However, fatigue after an infection sometimes is the only sign of myocarditis and this diagnosis may be revealed by an ECG, especially if there is an old ECG for comparison Citation3. We showed that an ECG was recorded in only 44% (27/61) of those seeking medical advice because of syncope, chest pain or palpitations. There are different explanations for this: chest pain was sometimes interpreted as musculo-skeletal pain, palpitations as anxiety. The patients were often totally asymptomatic during the visit to the physician. In some cases the patient reporting syncopal episodes was evaluated only for seizures with encephalography. However, it has been shown that EEG has little value in unselected patients with syncope Citation18,19. Syncope is often misinterpreted as a seizure disorder in long QT syndrome Citation20. Young patients with syncope are considered to be at low risk of cardiac disease while more than 80% of these have a vasovagal or psychogenic syncope, not associated with sudden death Citation21. However, the 1-year mortality risk of sudden death in patients with cardiac syncope ranges between 18 and 33%. In the initial evaluation of syncope a cardiac cause is considered more likely when syncope is preceded by palpitations or occurs during exercise Citation22. In our study one-third of the patients with syncope also had experienced palpitations, but only 30% of the cases were exercise-related.

Weaknesses and strengths of this study

In the atherosclerotic group there was a high degree of non-responders (53%) compared to the other groups (13%) that may give a false low number of symptomatic cases with atherosclerosis. Another weakness with the study is the retrospective interview design. This may imply an increase in the number of symptomatic cases because of a tendency to overemphasize symptoms. Symptoms may also be lost because of the time delay (3–10 years after the event). Also information about doctor's visits may be lost. Another problem is that the reported symptoms are common in the normal population and may not reflect cardiac disease.

We have also used other sources of information such as police and medical records. Police records sometimes include information about signs and symptoms reported in connection with the police inquest. The strength of this study is that it is a cohort design, covering the whole of Sweden, with forensic autopsy performed in all cases, and that details about signs and symptoms were available both by medical records (in 27%) and by interviews (in 79%).

Implications for prevention

In this national collection of SCD cases symptoms related to heart disease were common, but we could not link a certain sign or symptom to a specific diagnosis. Symptoms were often not interpreted as cardiac-related. In 4 out of 10 seeking medical advice an ECG was taken and three of these were pathological. This implicates that ECG is an underused tool in the investigation of symptoms, and we believe that a database with old ECGs easily available for comparison would be useful in the prevention of SCD. In one-third of those who were thoroughly investigated a cardiac diagnosis could be settled ante mortem, suggesting that more diagnoses could be found in non-investigated patients. If the ECG is abnormal, the symptoms severe or there is a family history of SCD, the patient should be referred to further cardiological evaluation since drugs or an ICD could be effective treatment options. In our study group a significant number had a non-structural heart disease, possibly with a genetic background. With the rapid progress of new genetic diagnostic methods, a molecular autopsy in the proband and clinical testing in the surviving family members may become a valuable complement for diagnosis and risk stratification of inherited cardiac diseases in the future.

This study was supported in part by a grant from the Norrbotten County Council. The authors wish to express their gratitude to the family members of the deceased for their cooperation and support.

References

- Myerburg R, Castellanos A. Cardiac arrest and sudden cardiac death. Heart disease: A textbook of cardiovascular medicine, E Braunwald. WB Saunders, Philadelphia 1997; 742–79

- Wisten A, Forsberg H, Krantz P, Messner T. Sudden cardiac death in 15–35 year olds in Sweden 1992–1999. J Int Med 2002; 252: 529–36

- Wisten A, Andersson S, Forsberg H, Krantz P, Messner T. Sudden cardiac death in the young in Sweden – electrocardiogram in relation to forensic diagnosis. J Int Med 2004; 255: 213–20

- Feinleib M, Simon AB, Gillum JR, Margolis JR. Prodomal symptoms and signs of sudden cardiac death. Circulation 1975; 52 Suppl 3: 155–9

- Liberthson, R. Sudden death from cardiac causes in children and young adults. N Engl J Med 1996;334:1039–44.

- Drory Y, Turetz Y, Hiss Y, Lev B, Fisman EZ, Pines A, et al. Sudden unexpected death in persons < 40 years of age. Am J Cardiol 1991; 68: 1388–92

- Kramer MR, Drory Y, Lev B. Sudden death in young soldiers. High incidence of syncope prior to death. Chest 1988; 93: 345–7

- Driscoll DJ, Edwards WD. Sudden unexpected death in children and adolescents. J Am Coll Cardiol 1985; 5: 118B–21B

- Krittayaphong R, Veerakul G, Nademanee K, Kangkagate C. Heart rate variability in patients with Brugada syndrome in Thailand. Eur Heart J 2003; 24: 1771–8

- Wichter T, Schulze-Bahr E, Eckardt L, Paul M, Levkau B, Meyborg M, et al. Molecular mechanisms of inherited ventricular arrhythmias. Herz 2002; 27: 712–39

- McKenna WJ, Deanfield J, Faraqui A, England D, Oakley C, Goodwin J. Prognosis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Role of age and clinical, electrocardiographic and hemodynamic features. Am J Cardiol 1981; 47: 532–8

- Dalal P, Fujisic K, Hupart P, Schwietzer P. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia: A review. Cardiology 1994; 85: 361–9

- Brembilla-Perrot B, Donetti J, de la Chaise A, Sadoul N, Aliot E, Juilliere Y. Diagnostic value of ventricular stimulation in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am Heart J 1991; 121: 1124–31

- Daliento L, Turrini P, Nava A, Rizzoli G, Angelini A, Buja G, et al. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy in young versus adult patients: Similarities and differences. J Am Coll Cardiol 1995; 25: 655–64

- Peters S. Right ventricular cardiomyopathy: Diffuse dilatation, focal dysplasia or biventricular disease. Int J Cardiol 1997; 62: 63–7

- Monserrat L, Elliott PM, Gimeno JR, Sharma S, Penas-Lado M, McKe WJ. Non-sustained ventricular tachycardia in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: An independent marker of sudden death risk in young patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003; 42(5)880–1

- McKenna WJ, England D, Doi YL, Deanfield J, Oakley C, Goodwin J. Arrhythmia in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. I: Influence on prognosis. Br Heart J 1981; 46: 168–72

- Kapoor W, Karpf M, Wieand S, Peterson J, Levey G. A prospective evaluation and follow-up of patients with syncope. N Engl J Med 1983; 309: 197–204

- Davis T, Freemon F. Electroencephalography should not be routine in the evaluation of syncope in adults. Arch Intern Med 1990; 150: 2027–9

- Moss AJ, Zareba W, Benhorin J, Locati EH, Hall WJ, Robinson JL, et al. ECG T-wave patterns in genetically distinct forms of the hereditary long QT syndrome. Circulation 1995; 92: 2929–34

- Risser W. Syncope in adolescents. Fam Phys 1985; 32: 117–23

- Brignole M, Alboni P, Benditt D, Bergfeldt L, Blanc JJ, Bloch Thomsen PE, et al. Guidelines on management (diagnosis and treatment) of syncope. Task force on syncope, European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2001; 22: 1256–306