Abstract

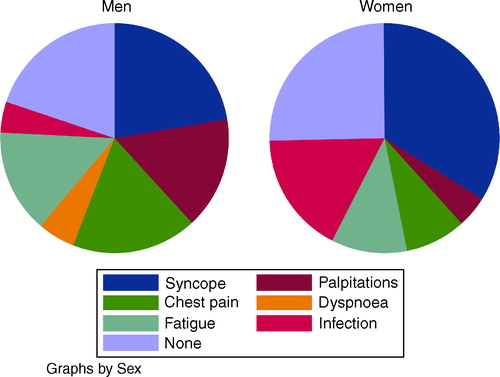

Objectives. To study the association between lifestyle and sudden cardiac death (SCD) in the young with special respect to athletic activities. Design. We compared lifestyle factors, collected from forensic and medical reports and from interviews with family members, in the Swedish cohort of individuals 15–35 years of age who had suffered an SCD during 1992–1999, with those of the control population of the same age group, obtained from national health registries. Results. Physical activity and body mass index (BMI) in men were the same as in the controls, whilst women had a higher BMI and a lower level of physical activity in the SCD group. Twenty-three per cent (32/138) were competing athletes in the SCD group and 29% in the control group (622/2131). Death during physical activity was more common in athletes (20/32) than in non-athletes (18/106) (p < 0.001). In coronary artery disease deaths, 11/15 (73%) were smokers and BMI was significantly higher than in the controls in both sexes. Conclusions. Young Swedish persons suffering SCD were very similar to the normal population with regard to lifestyle factors.

Introduction

An early case of sudden unexpected death was the Greek soldier Pheidippides who, according to the legend, suddenly died after having completed his run from Marathon to Athens in 490 bc to deliver the message of the victory over the Persians Citation1. These sudden unexpected deaths among young and fit persons are particularly shocking for the community when they occur in individuals who are perceived to be extremely healthy, and the deaths are usually given a lot of publicity. There are no precise data on the frequency of sudden cardiac death (SCD) in athletes, but in Minnesota high school athletes the annual incidence is estimated to be 1/200 000 during competition or practice Citation2. In a study from the Veneto region in Italy, athletes 12–35 years old are found to be at a 2.5-fold higher risk of SCD than non-athletes Citation3.

In Sweden 16 deaths diagnosed as myocarditis occurred among orienteers between 1979 and 1992, but no new cases have been reported within this sport after attempts were made to modify training habits and attitudes Citation4. However, the incidence of SCD in the young in Sweden has not declined; it has remained stable at about 1/100 000/year during the period 1992–1999 Citation5. We have previously analysed this SCD cohort with respect to ECG abnormalities, medical history, heredity and symptoms Citation6,7.

Is it possible to describe a group with a high risk of SCD? The aim of this study was to compare the young Swedish SCD cohort from 1992 to 1999 with respect to athletic activity and other lifestyle factors with a control population of the same age group Citation5.

Methods

Subjects

The study population included the Swedish SCD cohort from 1992 to 1999, consisting of all cases of SCD in the age group 15–35 years old and registered in the national forensic database. SCD was defined as a witnessed, natural, unexpected death from cardiac causes occurring within 1 h after onset of symptoms in a previously healthy person, or an unwitnessed natural unexpected death of a person observed to be well within 24 h of being found dead Citation8. The study group consisted of 162 cases (115 men, 47 women).

Data collection

We used information from forensic, police and medical records and from contacts with relatives by a questionnaire and by telephone interview, comprising information on athletic activity, medical history, substance use, food habits, among others. For a more thorough description of the methodology and questionnaire we refer to a previous paper Citation7.

Definitions

We defined physical activity as regular training of a sports activity; either an individual activity such as jogging or a team sport, e.g. European football. An individual was defined as an athlete if he/she participated in an organized team or individual sport which required regular training and competitions Citation9. Participation in competitions is what differentiated athletes from non-athletes.

Anthropometric variables

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from data in the forensic reports.

Comparison with the control populations

We compared our findings concerning competitive activity and training intensity in athletes with results from a report on the Swedish population (1048 men and 1083 women, ages 15–35, in the year 1999) from the Swedish Sports Confederation Citation10. Information on allergy, medication, BMI, smoking and physical activity was collected from a national health and lifestyle survey of the Swedish population in the years 1996 and 1997, 1971 men and 1924 women in the ages 16–34 Citation11. Both studies had been carried out on behalf of the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare and were used as control populations in this study.

Statistical analyses

For comparison of BMI with the control group, one-sample t-test was used. For comparison of categorical variables (training degree, smoking, snuff use, etc.) Fisher's exact t-test was used. A two-sided p-value less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. All statistical analyses were carried out using the “immediate” commands in the program Stata SE version 8.2 Citation12.

Results

In 128/162 cases (79%) the informants completed the questionnaires. In 10 further cases we obtained information from forensic or medical records. Thus we obtained a total of 138/162 (85%); 97/115 (84%) of these were men and 41/47 (87%) were women. In 10 cases no informant could be located, 13 cases did not respond and 11 individuals declined to participate.

Athletes

In the SCD group there were 32/138 (23%) athletes, 28 men and 4 women. They represented 14 different sports (11 European football, 6 floor ball, 2 running, 2 riding, 2 orienteering, and 1 each of handball, bowling, jujitsu, snowboard, figure skating, triathlon, dancing, ice hockey and karate). Five were regarded as top athletes (of national standard). Three of them had been recommended to avoid hard training because of symptoms such as syncope in connection with sports activity (one case of orienteering, one case of ice hockey) or post-infectious fatigue (one case of triathlon). Three of the other athletes were also recommended not to train because of serious symptoms (two cases of European football, one case of athletics).

Diagnoses

Apart from a higher prevalence of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) in the athletic group, there were no differences in diagnostic spectrum between the athletes and non-athletes ().

Circumstances at death

Death during training or exercise was more common in athletes than in non-athletes (20/32; 63% vs 18/106; 17%, p<0.001). Of the top athletes, all (5/5) died during physical activity. In our study 17/20 (85%) of the athletes who died during physical activity had an underlying structural cardiac disease.

Athletes in the SCD group vs the control population ()

We found a lower proportion of athletes in the SCD group (23%) than in the control population (29%), but the frequency of athletes with a high training intensity (at least three times a week) was approximately the same.

Table I. Training intensity of a group of athletic victims of sudden cardiac death and that of a control group.

Physical activity, BMI, smoking and snuff use in the SCD group vs the control population ()

In men there was no significant difference in physical activity between the SCD group and the control population. Many women in the SCD group had a low level of physical activity as compared with the control group (26/41; 63% vs 685/1924; 36%, p < 0.001).

Table II. Characteristics of cases of sudden cardiac death in the young, and those of a control group.

BMI was available in 141/162 (87%). The mean BMI in men was the same in the SCD and in the control groups whilst in women BMI was significantly higher in the SCD group. In SCD men with atherosclerosis, the mean BMI was higher than in the control group (27 vs 24; p<0.002).

Smoking in men was more common in the SCD group than in the control group due to a higher proportion of smokers in the atherosclerotic group where 7/11 (64%) of the subjects were smokers. There was no significant difference in smoking habits between SCD and control women. There were fewer snuffers (only men) in the SCD group than in the control group.

Medications ()

In the SCD group the use of asthma medications at least 2 weeks a year was the same as in the control population. Women's use of contraceptives was less common than in the control population. Other drugs used in the SCD group were: beta-blockers (n=7), acetylsalicylic acid, lipid-lowering drugs, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (n=1), medication against gastric ulcer and inflammatory bowel disease (n=2 each) and replacement therapy in hypothyroidism (n=1).

Non-cardiac diseases

In the SCD group there were two cases of inflammatory bowel disease (autopsy diagnoses dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)), and one case of dystrophia myotonica (autopsy diagnosis DCM). Allergy or asthma was present in 10/41 women (24%) and 22/97 men (22%) in the SCD group. The corresponding figures in the control group were 609/1971 (31%) in men and 652/1924 (34%) in women.

Toxicology

Individuals with alcohol levels above 0.1% or other drugs in toxic doses were not included in the original study Citation5. Alcohol in concentrations between 0.01 and 0.089% was found in 18/162 (11%) in the SCD group. Some SCD patients had traces of drugs, all in adequate treatment levels: paracetamol (six subjects), antidepressants (three subjects), antibiotics (two subjects), beta-blocking drugs (two subjects), diuretic (one subject) and resuscitation drugs (eight subjects).

Food habits

In the SCD group most cases had normal food habits. However, two were vegetarians who ate fish and milk products and one was a vegan. Three persons ate ordinary food but avoided milk products.

Discussion

This study is part of an investigation of young patients suffering an SCD in Sweden 1992–1999. To our knowledge lifestyle factors have not been systematically studied before in a young SCD cohort covering a whole nation.

Other studies

Previous studies on lifestyle in a young SCD group mostly have been restricted to athletic activity and the results have been contradictory. The incidence figures of SCD in athletes differ between the USA and Europe. In a national retrospective study from the USA the estimated rate of non-traumatic sports’ deaths in high school and college athletes was 0.75/100 000/year for men and 0.13/100 000/year for women during 1983–1993. The cases were gathered from different sources by the National Center for Catastrophic Sports Injury Research, and the number of participants was estimated through information from sports associations. In 78% there was a cardiovascular background; HCM being the most frequent cause of death, coronary anomalies the second most common cause Citation13. In Minnesota high school athletes the incidence of SCD was small and HCM the most common autopsy diagnosis Citation2. The number of deaths and participants in that study was based on an insurance programme mandatory for all student athletes.

So far only one study has compared the risk of SCD in athletes and non-athletes. In a prospective study from the Veneto region in Italy, the incidence of SCD in athletes 12–35 years old was 2.1/100 000/year as compared with 0.7/100 000/year in non-athletes Citation3. The athletic population in that region is registered in the Sports Medicine Data Base of the Veneto Region of Italy and has undergone pre-participation screening by history, physical examination, 12-lead ECG and limited exercise testing as required by Italian law. The higher frequency of SCD in athletes in Italy, as compared with those in the USA, may be due, in part, to the prospective study design. In Italy there is a higher probability of identifying cases of SCD in competing athletes because they are registered in a database. Otherwise, the higher risk of SCD in athletes in the Veneto region is somewhat surprising because the pre-participation screening programme for athletes has been in use since 1971. On the other hand, the pre-participation screening programme may explain why HCM is an uncommon cause of death in young competitive athletes in Italy as compared with the USA Citation14,15. In addition, ARVC, which is difficult to detect at screening, is a more commonly found cause of death in Italy Citation3. The high incidence of ARVC in Italy may also be due to genetic factors; since the disease is endemic in the Veneto region Citation16.

The Swedish SCD cohort

Athletes

In our study there was a lower percentage of athletes in the SCD group (23%) than in the control population of the same age (29%). We compared our results concerning athletic activity with a report on the Swedish population of the same age from the Swedish Sports Confederation. The high frequency of self-reported athletes in this report may reflect either a tendency to overestimate competing habits or that the concept of competitive activity is used in a very broad sense by the respondent. Most likely, we had no overrepresentation of competing athletes in the SCD group as compared with the control population. If we compare our results with the Italian study, their athletic pre-screened SCD group probably represented a much more selected group (8% of the total population) Citation3 competing at a higher level than our self-reported athletes (29% of the control population). It is estimated that Italian athletes who have regularly undergone medical screening probably constitute much less than 50% of all potential candidates Citation17.

The sports with the highest number of deaths in our study were different ball sports such as European football, floor ball and handball. Together those sports represented more than half of the cases. The predominance of ball sports in athletic SCD cases also has been shown in other studies Citation13,15.

Is physical activity dangerous?

We saw that a high percentage of athletes died during physical activity (63%), but almost 4 out of 10 died during other activities or sleep. Other studies have suggested that physical activity can trigger SCD Citation3,13,15,18. In the non-athletic population 10–25% of SCD is exercise related, in agreement with 17% in our study. The European Society of Cardiology has recently published a consensus document recommending screening of all young competing athletes involved in organized sports programmes with implementation of a screening protocol based on a 12-lead ECG Citation19. However, many young people today participate in different recreational sports on a regular basis, often with a high level of training intensity. It is not evident that competitive physical activity increases the risk of a cardiovascular event more than non-competitive physical activities.

Gender difference

In our study there were seven times more men (28) than women Citation4 in the athletic SCD group, a gender difference of the same magnitude as shown in other studies Citation3,13,18. One reason for this great difference between the genders might be that women are more rarely involved in high intensity training than men. Recently male gender was reported to be, in itself, a risk factor for sports-related sudden death, probably because of the greater prevalence of cardiomyopathies and premature coronary artery heart disease Citation19.

Physical activity and BMI

The male SCD group seemed to be similar to the control population with regard to physical activity and BMI. In contrast, the female SCD group had a lower level of physical activity and a higher BMI. This might be an adaptation to a silent cardiac disease among the women. As expected, the patients belonging to the atherosclerotic group differed from the others. Both men and women had a higher BMI than the controls and 75% were smokers.

Medication, allergy

Asthma and the use of asthma medications were as common in the SCD group as in the control population. The incidence of sudden death in patients with bronchial asthma is increasing in all age groups, and it has been suggested that β agonists may contribute to death in some patients Citation20. On the whole the use of medication was low in the SCD group and at the same level as in the control population; none of the cases of SCD in our group had blood levels of β agonists at the post-mortem analysis.

Commotio cordis

There were two cases of blunt impact to the chest in this study, both occurring during participation in European football. In one, the ball struck the chest of the player and in the other there was a collision between two players. In these patients the autopsy showed DCM and ARVC, respectively. Although uncommon, it has been suggested that sudden death may result from ventricular arrhythmia induced by a blow to the chest during a vulnerable phase of the heart in the absence of demonstrable underlying cardiovascular disease Citation21.

Strengths and limitations

A weakness with this study was the non-response in one-fifth of the SCD group, more common in the atherosclerosis group (53% non-response) than in the other diagnostic groups (13% non-response). There was also a bias involved in questioning relatives 3–10 years after the event. This could imply problems with remembering details but also a tendency to exaggerate. In the control group the respondents were the participants themselves. The weaknesses with a retrospective study are also applicable to our investigation. A strength with our study was that our SCD group was selected from a national database that included all cases of SCD in which a forensic autopsy had been performed. It is also a strength that we had two national health investigations from the study period for comparison.

Conclusion

We found the SCD group very similar to the control population, both with regard to competitive athletic activity and with regard to other lifestyle factors, such as training habits, BMI, use of medication and smoking. Athletic activity has been discussed as a presumptive risk factor or triggering factor for SCD and The European Society of Cardiology has recently published recommendations concerning screening of all young competing athletes Citation19. We conclude that since no risk group could be defined, a simple cardiac screening procedure including both athletes and non-athletes should be considered.

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the family members of the deceased for their cooperation and support. The study was funded by an unrestricted research grant from the Norrbotten County Council, Luleå, Sweden.

References

- Herodotus. The histories. London: Everyman; 1991.

- Maron BJ, Gohman TE, Aeppli D. Prevalence of sudden cardiac death during competitive sports activities in Minnesota high school athletes. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998; 32: 1881–4

- Corrado D, Basso C, Rizzoli G, Schiavon M, Thiene G. Does sports activity enhance the risk of sudden death in adolescents and young adults?. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003; 42: 1959–63

- Larsson E, Wesslén L, Lindquist O, Baandrup U, Eriksson L, Olsen E, et al. Sudden unexpected cardiac deaths among young Swedish orienteers – morphological changes in hearts and other organs. APMIS 1999; 107: 325–6

- Wisten A, Forsberg H, Krantz P, Messner T. Sudden cardiac death in 15–35 year olds in Sweden 1992–1999. J Int Med 2002; 252: 529–36

- Wisten A, Andersson S, Forsberg H, Krantz P, Messner T. Sudden cardiac death in the young in Sweden – electrocardiogram in relation to forensic diagnosis. J Int Med 2004; 255: 213–20

- Wisten, A, Messner, T. Symptoms preceding sudden cardiac death in the young are common but often misinterpreted. Scand Cardiovasc J. In press, 2005.

- Myerburg R, Castellanos A. Cardiac arrest and sudden cardiac death. Heart disease: A textbook of cardiovascular medicine, E Braunwald. WB Saunders, Philadelphia 1997; 742–79

- Maron BJ, Mitchell BD. Recommendations for determining eligibility for competition in athletes with cardiovascular abnormalities. J Am Coll Cardiol 1994; 24: 848–50

- Swedish Sports Confederation. Svenska folkets tävlings- och motionsvanor; 1999.

- Statistics Sweden. The Swedish survey of living conditions; 2000. Available at: http://www.scb.se.

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software. Release 8.2 ed. College StationTX: Stata Corporation; 2003.

- Van Camp SP, Bloor CM, Mueller F, Cantu RC, Olson HG. Nontraumatic sports death in high school and college athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1995; 27: 641–7

- Corrado D, Basso C, Schiavon M, Thiene G. Screening for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in young athletes. N Engl J Med 1998; 339: 364–9

- Maron BJ, Shirano J, Poliac L, Mathenge R, Roberts W, Mueller F. Sudden death in young competitive athletes. Clinical, demographic and pathological profiles. JAMA 1996; 276: 199–204

- Rampazzo A, Nava A, Danieli GA, Buja G, Daliento L, Fasoli G, et al. The gene for arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy maps to chromosome 14q23-q24. Hum Mol Genet 1994; 3: 959–62

- Pelliccia A, Maron BJ. Preparticipation cardiovascular evaluation of the competitive athlete: Perspectives from the 30-year Italian experience. Am J Cardiol 1995; 75: 827–9

- Burke AP, Farb A, Virmani R, Goodin J, Smialek J. Sports-related and non-sports-related sudden cardiac death in young adults. Am Heart J 1991; 121: 568–75

- Corrado, D, Pelliccia, A, Björnstad, H, Vanhees, L, Biffi, A, Borjesson, M, et al. Cardiovascular pre-participation screening of young competitive athletes for prevention of sudden death: Proposal for a common European protocol, Eur Heart J 2005;26:516–24.

- Hunt, LW, Silverstein, CE, O'Connell, EJ, O'Fallon, WM, Yunginger, JW. Accuracy of the death certificate in a population-based study of asthmatic patients. JAMA 1993;269:1947–52.

- Maron BJ, Poliac L, Kaplan J, Mueller F. Blunt impact to the chest leading to sudden death from cardiac arrest during sports activities. N Engl J Med 1995; 333: 337–42