Abstract

Objectives. We aim to compare patient characteristics and coronary risk factors among participants and non-participants in a survey of CHD patients. Methods. A cross-sectional study explored characteristics and risk factors in patients hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction and/or revascularization. Study data collected from hospital medical records were compared between participants (n = 1127, 83%) and non-participants (n = 229, 16%), who did not consent to participation in the clinical study. Results. Non-participants showed statistically higher prevalence of women (28% versus 21%), ethnic minorities (6% versus 3%), patients living alone (26% versus 19%), depression (19% versus 6%), anxiety (9% versus 3%), hypertension (54% versus 43%) and diabetes (24% versus 17%). Significantly higher multi-adjusted odds ratios were found for Charlson comorbidity index 3.4 (95% confidence interval (CI), 2.8, 4.3) and depression 14.5 (4.4, 121.5) in non-participants. Conclusions. Non-participants do have higher prevalence of important coronary risk factors compared to participants, and risk factor control may thus be overestimated in available prevention studies. Patients with somatic comorbidity and depression appear to be at particular risk of non-participation in the present study. New strategies accounting for the causes of nonadherence are important to improve secondary prevention in CHD.

Introduction

Epidemiologic observational studies like the EUROASPIRE program [Citation1,Citation2] and cardiovascular disease registries like REACH [Citation3] provide important information on the quality of secondary coronary prevention, through monitoring the control of lifestyle and medical risk factors, treatment patterns, and outcomes. Valid estimates, however, presuppose that the sample of participants in clinical studies is representative of the respective population of coronary heart disease (CHD) patients. The EUROASPIRE 4 Study did not only show that implementation of evidence-based guidelines on secondary prevention was far from optimal, but also a low average interview rate (i.e. 49%).[Citation2] It was proposed by the authors that this may introduce a potential bias since those who did not participate in the study were more likely to have unhealthy lifestyles and coronary risk factors.[Citation2] Recent data from the large National Cardiovascular Data Registry in US found that trial participants had a lower risk profile and a more favorable prognosis compared with the large population with established CHD eligible for but not enrolled in a clinical trial.[Citation4] However, patient characteristics of non-participants other than their coronary risk profile were limited in these studies.

Evidence from surveys from general populations without established cardiovascular disease show that non-participants are more likely to be men [Citation5] and with a lower socioeconomic status (i.e. lower education, poorer employment status, and less likely to be married) when compared to study participants,[Citation6–8] while this association is less consistent for age and ethnicity.[Citation5,Citation9] Studies that have linked population-based studies to health registries report higher prevalence of psychiatric disorders [Citation10,Citation11] and a higher rate of hospitalization and mortality [Citation8,Citation12] among non-participants. To our knowledge, no previous studies have explored the differences between participants and non-participants with respect to socio-demographic and clinical characteristics in risk factor studies of patients with established CHD. This knowledge is needed to identify sub-groups of CHD patients that require particular measures for recruitment to clinical studies on coronary prevention.

The NORwegian CORonary Prevention (NOR-COR) Study was designed to identify socio-demographic, clinical, and psychosocial factors associated with unfavorable coronary risk factor control and subsequent cardiovascular events.[Citation13] The purpose of the present NOR-COR sub-study is to compare socio-demographic factors, coronary diagnosis and risk factors, coronary interventions, medication, and prevalence of somatic and psychiatric comorbidity between participants and non-participants. Data was obtained from hospital medical records during the index coronary event. We hypothesize that non-participants include a high-risk patient subgroup in particular need of improved secondary prevention when compared with participants.

Methods

A cross-sectional study with a retrospective component was conducted at two Norwegian hospitals (Drammen and Vestfold). Consecutive patients aged 18–80 years with a first or recurrent coronary event defined as acute myocardial infarction (ICD-10 I21)), coronary artery by-pass graft operation (CABG), elective or emergency percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) were identified from hospital discharge lists from 2011 to 2014. Patients not able to understand the Norwegian language, with cognitive impairment, living in nursing homes, with history of psychosis or drug abuse, and patients with short life expectancy due to terminal heart, lung, liver, kidney or malignant disease were excluded. Eligible patients were mailed an invitation letter with study information, a self-report questionnaire, and an appointment for the clinical examination with the collection of venous blood samples. In addition, data from the hospital medical record were registered. The concept, design, methods and baseline characteristics of the NOR-COR study have been described in detail elsewhere.[Citation13]

The study protocol was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics – South East Norway. In the sub-group of non-participants who did not respond to the study invitation, particular exemption from obtaining consent for the use of hospital medical record data, was given by the Committee of Ethics as the likelihood of positive health benefit exceeded the risk and burden of research entails. Patients who responded and refused analysis of hospital record data (refusers) were excluded.

Study assessments

Study data from the hospital medical records at the time of the index coronary event were registered by an experienced cardiologist. Information about comorbidity was supplied with information from previous hospital admissions at the somatic and psychiatric department, outpatient clinic visits, and clinical examinations (i.e. echocardiography, laboratory tests, imaging studies, etc.). First and second generation patients from Asia, Africa and South America were categorized as ethnic minorities. Time since the index coronary event was calculated from index event to the date of study inclusion for participants and date of the planned study inclusion for non-participants.

Type of coronary event was categorized as (i) ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), (ii) non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), (iii) unstable or (iv) stable angina pectoris. Angiographic findings were classified as atherosclerosis without significant stenosis, and single-vessel disease or multi-vessel disease when significant stenoses were present. The number of previous coronary events was categorized as 1 or >1. Participation in cardiac rehabilitation programs was extracted from the hospital medical records and separate lists from the cardiac rehabilitation department. Coronary risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, smoking status) and cardiovascular medication (anti-thrombotics, anticoagulants, statins, ACE-inhibitors, angiotensin-2-receptor blockers, beta-blockers, diuretics and calcium channel blockers) were recorded from the hospital medical records. Somatic comorbidity (heart failure, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, liver disease, transitory ischemic attack/stroke or peripheral artery disease) was summarized according to the Charlson comorbidity index,[Citation14] with higher values indicating increasing comorbidity. Psychiatric comorbidity was defined as a clinical diagnosis of anxiety or depression registered in the hospital medical records at the time of the index event. The use of anxiolytics or antidepressants was noted. Patients were categorized as living alone or in a relationship. Low socio-economic status was defined as being unemployed or annuity on temporary or permanent disability benefit.

Statistical analysis

All study data were analysed using SPSS versus 21 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Differences between participants and non-participants were analyzed using an independent sample t-test for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to calculate crude- and multi-adjusted odds ratio (OR) for not participating in the study. In the multi-adjusted analysis we controlled for variables with significant association in the crude model.

Results

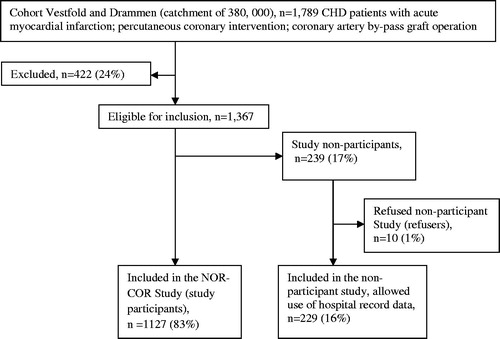

Out of 1789 patients, aged 18–80 years, with an index coronary event, 422 (23.6%) were excluded due to the following conditions: cognitive impairment (n = 28); psychosis (n = 18); drug abuse (n = 10); short life expectancy (n = 136); dead (n = 161); not able to understand the Norwegian language (n = 44); and other (n = 26). A total of 1367 patients were asked to participate and 1127 (83%) admitted to participation and were included in the NOR-COR study with an index coronary event on average 17.1 (2–38) months prior to study inclusion. Of the 239 non-participants, 191 patients consented to registration of their hospital medical record data, whereas 38 patients did not respond to this invitation. Accordingly, patient data for 229 non-participants (96% of all non-participants) are compared with the respective data for the 1,127 participants. Ten patients actively refused their hospital medical record to be used in the non-participants study and were excluded. The study flow chart is presented in .

Comparisons of socio-demographic data, clinical characteristics and coronary risk factors between the two groups are presented in . There were no significant differences between participants and non-participants in time from index event to study inclusion or planned study inclusion, respectively. We found no significant differences in average age at the index event. Compared to participants, non-participants included significantly more women (28% versus 21%), ethnic minorities (6% versus 3%) and patients who were living alone (26% versus 19%). There were no significant differences in the type or number of coronary events, angiographic findings or coronary intervention between the participants and non-participants. Non-participants had a significantly higher prevalence of hypertension (54% versus 43%) and diabetes (24% versus 17%), and a significantly lower participation rate in the cardiac rehabilitation program (28% versus 50%) compared with participants. The prevalence of current smoking did not differ significantly between the two groups.

Table 1. Comparison of socio-demographic factors, clinical characteristics and risk factors between participants and non-participants.

Except for atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter and stroke/transitory ischemic attack being more frequent among non-participants, the prevalence of various somatic comorbidities listed in did not differ significantly between the two groups. However, non-participants had a significantly higher Charlson comorbidity score (p < 0.05). Except for insulin, there were no significant differences in prescription of somatic medication. Compared to study participants, the prevalence of anxiety and depression were three times higher among non-participants whose prescription rate of psychotropic drugs was 2.5 times higher. shows the crude and multi-adjusted odds ratios for non-participation. In the multi-adjusted estimates, odds ratios for the Charlson comorbidity index and depression were significantly higher among non-participants than participants.

Table 2. Comparison of somatic and psychiatric comorbidity and medication between participants and non-participants.

Table 3. Multi-adjusted odds ratio for not participating in the NORwegian CORonray Prevention Study.

Discussion

Non-participants had a considerably higher prevalence of depression and anxiety registered in their hospital medical records and the most striking finding was the 15 times higher likelihood that a patient with depression is a non-participant rather than a participant. Furthermore, non-participants had a higher prevalence of somatic comorbidity and the risk factors diabetes mellitus and hypertension, and a lower participation rate in the cardiac rehabilitation program.

Despite the potential importance of participating in health surveys, patient recruitment is often suboptimal in clinical epidemiologic studies due to a number of reasons, including unwillingness of patients to participate, the burden of additional procedures, declining volunteerism and distrust in clinical research.[Citation9] The participation rate was not reported in a worldwide study on risk factor management in CHD patients,[Citation3] while the participation rate was only 50% in the EUROASPIRE studies.[Citation1,Citation2] Knowledge about the non-participants is important for the generalizability and external validity of studies leading to more precise assumptions and conclusions.[Citation9] On the other hand, non-participation in epidemiologic studies has the largest implications for prevalence studies, while its impact may be less marked in studies of associations between exposures and outcomes which is the overall aim of the NOR-COR study.[Citation9] Recruitment procedures for both epidemiologic and randomized intervention studies in coronary prevention should be further developed to account for the sub-groups of CHD patients in particular need of better secondary prevention and rehabilitation.

We found a higher burden of somatic comorbidity among the non-participants who are at highest risk of subsequent events.[Citation15] In accordance with the results from the EUROASPIRE Study,[Citation2] we also found a higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus and hypertension. It is therefore concerning that these underserved patients with the strongest need for structured prevention and rehabilitation had the lowest participation rate in cardiac rehabilitation. Our data indicate that previous studies have underestimated the true standard of secondary coronary prevention.[Citation2,Citation3] The risk of all-cause mortality has previously reported to be significantly higher three years after screening among people who did not participate in a screening study for cardiovascular disease compared with participants.[Citation16] Whether CHD patients who do not participate in studies also have a poorer prognosis as regards to CVD morbidity and mortality needs to be addressed.

The prevalence of depression and anxiety among study participants was 6% and 3%, respectively, and substantially lower than that previously reported in patients with established CHD, where approximately 20% of patients met the diagnostic criteria for major depression, and an even larger percentage had subclinical levels of depressive symptoms.[Citation17] The qualitative differences rather than the numerical level of prevalence for anxiety and depression should thus be emphasized in the present study (cf. Limitations). The significantly higher prevalence among non-participants is a matter of concern, as anxiety and depression are associated with a 1.5- to 3-fold increased risk of subsequent cardiovascular events in CHD patients.[Citation18,Citation19]

Depression is also associated with a poor coronary risk profile,[Citation20] medication non-adherence,[Citation21] and drop-out from cardiac rehabilitation.[Citation22] As we found depression to be the most convincing findings among non-participants, the present study emphasizes the potential importance of successful management of psychosocial factors for coronary prevention and rehabilitation.[Citation23] In the NOR-COR Study, we have recently introduced a systematic step-wise approach for the development of a more tailored psychosocial intervention programs according to the patients behavioural profile.[Citation13] This program may hopefully contribute to improve secondary prevention for CHD patients with psychosocial factors, including anxiety and depression.

Limitations

Study data were retrospectively obtained from the hospital medical records with the possibility for a reporting bias. For example, the prevalence estimates of depression and anxiety in the present study are most likely too low as they are based on hospital medical records that are less sensitive and accurate compared to standardized psychiatric diagnostic assessments. However, the frequency of presumed underreporting is most likely equally distributed between participants and non-participants. Moreover, the delayed patient recruitment 2-–6 months after the index coronary event may have influenced the results, with the possibility that patients dying during prior to inclusion could be more seriously ill and more depressed than living non-responders. Smoking status was incompletely reported and could only be categorized as current smoking versus non-smoking. Thus, quantification of smoking was not possible. Important coronary risk factors such as diet, body weight and physical activity could not be evaluated due to incomplete information available in the actual hospital medical records. Non-participants represent a heterogeneous group of patients including patients who refused to participate and patients who were unable to provide informed consent. The reasons for non-participation were not recorded in the present study. Accordingly, stratified analyses based on the reasons for non-participation could not be performed.

Conclusions

Non-participants do have higher prevalence of important coronary risk factors compared to participants. The risk factor control in CHD patients may thus be overestimated in available prevention studies. Patients with somatic comorbidity and depression appear to be at particular risk of non-participation. New strategies accounting for the causes of nonadherence are important to improve secondary prevention in CHD.

Acknowledgments

The NOR-COR project originates from and is based at Department of Medicine Drammen Hospital and the study is funded and carried out at the sections for cardiology at Drammen and Vestfold Hospitals. The concept is developed by the project in close collaboration with communities at the University of Oslo, with methodological expertise in behavioral sciences. The authors thank study patients and all study personnel in the NOR-COR Research group for their invaluable help in completing the study.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Funding

The study was funded by research grants from the participating hospitals.

References

- Kotseva K, Wood D, De Backer G, et al. Cardiovascular prevention guidelines in daily practice: a comparison of EUROASPIRE I, II, and III surveys in eight European countries. Lancet. 2009;373:929–940.

- Kotseva K, Wood D, De Bacquer D, et al. EUROASPIRE IV: A European Society of Cardiology survey on the lifestyle, risk factor and therapeutic management of coronary patients from 24 European countries. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016;23:636–648.

- Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Ohman EM, et al. International prevalence, recognition, and treatment of cardiovascular risk factors in outpatients with atherothrombosis. JAMA. 2006;295:180–189.

- Udell JA, Wang TY, Li S, et al. Clinical trial participation after myocardial infarction in a national cardiovascular data registry. JAMA. 2014;312:841–843.

- Dunn KM, Jordan K, Lacey RJ, et al. Patterns of consent in epidemiologic research: evidence from over 25,000 responders. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:1087–1094.

- Dryden R, Williams B, McCowan C, et al. What do we know about who does and does not attend general health checks? Findings from a narrative scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:723

- Korkeila K, Suominen S, Ahvenainen J, et al. Non-response and related factors in a nation-wide health survey. Eur J Epidemiol. 2001;17:991–999.

- Drivsholm T, Eplov LF, Davidsen M, et al. Representativeness in population-based studies: a detailed description of non-response in a Danish cohort study. Scand J Public Health. 2006;34:623–631.

- Galea S, Tracy M. Participation rates in epidemiologic studies. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17:643–653.

- Hansen V, Jacobsen BK, Arnesen E. Prevalence of serious psychiatric morbidity in attenders and nonattenders to a health survey of a general population: the Tromso Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:891–894.

- Knudsen AK, Hotopf M, Skogen JC, et al. The health status of nonparticipants in a population-based health study: the Hordaland Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172:1306–1314.

- Jousilahti P, Salomaa V, Kuulasmaa K, et al. Total and cause specific mortality among participants and non-participants of population based health surveys: a comprehensive follow up of 54 372 Finnish men and women. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59:310–315.

- Munkhaugen J, Sverre E, Peersen K, et al. The role of medical and psychosocial factors for unfavourable coronary risk factor control. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2016;50:1–8.

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, A KL. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383.

- Fox KA, Carruthers KF, Dunbar DR, et al. Underestimated and under-recognized: the late consequences of acute coronary syndrome (GRACE UK-Belgian Study). Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2755–2764.

- Walker M, Shaper AG, Cook DG. Non-participation and mortality in a prospective study of cardiovascular disease. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 1987;41:295–299.

- Thombs BD, Bass EB, Ford DE, et al. Prevalence of depression in survivors of acute myocardial infarction. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:30–38.

- Lichtman JH, Froelicher ES, Blumenthal JA, et al. Depression as a risk factor for poor prognosis among patients with acute coronary syndrome: systematic review and recommendations: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129:1350–1369.

- Roest AM, Martens EJ, de Jonge P, et al. Anxiety and risk of incident coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:38–46.

- Ziegelstein RC, Fauerbach JA, Stevens SS, et al. Patients with depression are less likely to follow recommendations to reduce cardiac risk during recovery from a myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1818–1823.

- Gehi A, Haas D, Pipkin S, et al. Depression and medication adherence in outpatients with coronary heart disease: findings from the Heart and Soul Study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2508–2513.

- Swardfager W, Herrmann N, Marzolini S, et al. Major depressive disorder predicts completion, adherence, and outcomes in cardiac rehabilitation: a prospective cohort study of 195 patients with coronary artery disease. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:1181–1188.

- Pogosova N, Saner H, Pedersen SS, et al. Psychosocial aspects in cardiac rehabilitation: From theory to practice. A position paper from the Cardiac Rehabilitation Section of the European Association of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2015;22:1290–1306.