Abstract

Objective. A substantial part of deaths and readmissions in octogenarians with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is assumed to be of non-cardiovascular causes. However, limited data on cause-specific long-term mortality and hospital readmissions are available. This study was aimed to investigate 5-year cause-specific deaths and re-hospitalizations as well as their prognostic predictors among octogenarians with ACS managed with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Methods. A total of 181 octogenarians managed with PCI on ACS indication during 2006–2007 at Sahlgrenska University Hospital were included. The time-period was chosen to allow a follow-up period of five years. Results. All-cause 5-year mortality was 46%. Approximately 70% of deaths were cardiovascular. All-cause hospital readmissions were 71%. The majority of readmissions were due to non-cardiovascular diseases, 61% of all readmissions. Cox proportional-hazard regression analyses for cardiovascular mortality identified female sex and culprit lesion in left coronary arteries as independent predictors. Negative binomial regression models showed female sex and complications during index hospitalization as independent predictors of increased cardiovascular re-hospitalizations and prior smoking as independent predictor of increased non-cardiovascular re-hospitalizations. Conclusions. In an octogenarian cohort presented with ACS treated with PCI, cardiovascular diseases were the main causes of deaths, whereas non-cardiovascular diseases were the main causes of re-hospitalizations.

Introduction

A substantial part of deaths and readmissions in octogenarians with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is assumed to be due to non-cardiovascular causes. However, limited data on causes of deaths and readmissions are available in octogenarians with ACS. This is a clinically relevant issue, not only because ACS often occurs in the elderly but also the prognosis of ACS in the elderly might be changed in the era of reperfusion therapy including percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).[Citation1–6] PCI is without a doubt the most important therapy that affects prognosis in ACS. Old age is associated with higher in-hospital mortality and frequent complications, such as renal failure and bleedings, after PCI.[Citation7,Citation8] However, results from studies on mid- and long-term outcomes of PCI are inconsistent.[Citation9–16]

Since co-morbidities increase with age, it is assumed that non-cardiovascular causes of deaths or readmissions increase among octogenarians. For instance, in elderly patients with heart failure, only 57% of deaths can be attributed to cardiovascular causes.[Citation17] However, the extent to which non-cardiovascular causes contribute to deaths or readmissions in octogenarians with ACS remains unknown, particularly after PCI. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate the causes of deaths, readmissions, and their prognostic predictors in octogenarians with ACS, five years after PCI.

Materials and methods

Study cohort

Among 504 patients aged ≥80 years who presented with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) at Sahlgrenska University Hospital during 2006, only 84 patients were treated with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Patients who did not undergo PCI were older and sicker with a higher mortality rate, 89%. Because the aim of the present study was to study the outcome after ACS in patients treated with PCI, we also included patients from 2007 to get a sufficient number. Altogether, 237 patients aged ≥80 years were treated with PCI with ACS indication during 2006–2007 at Sahlgrenska University Hospital. Fifty-six patients were excluded due to the fact that these patients did not belong to the catchment area of Sahlgrenska University Hospital, since medical records from other hospitals were not accessible. Only patients treated with PCI on ACS indication (n = 181) were included in the present study and retrospectively studied from January 2 to May 30, 2012. Only 8 patients were ≥90 years. Baseline parameters covering social, functional, and medical domains were entered into a database (). The time-period of 2006–2007 was chosen to allow a follow-up period of five years. PCI procedures for the specified age group and time period were identified from medical records. The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee at the University of Gothenburg.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics: comparison between men and women.

Laboratory analyses

All laboratory variables were analyzed, as routine protocol, by the Clinical Chemistry Laboratory at Sahlgrenska University Hospital. Almost all our patients were of the same ethnicity. We needed only to adjust for age, sex and weight. Therefore, we used the Cockcroft–Gault formula to calculate the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) in mL/min.

Clinical outcome data

The primary endpoint was cause-specific mortality and hospital readmissions five years following PCI. Data on causes of death were obtained from the death registry of the National Board of Health and Welfare in Sweden. The causes of death were classified according to ICD-10. The Automated Classification of Medical Entities (ACME) program was used to select the underlying cause of death. ACME program selects an underlying cause of death by applying the WHO rules to the ICD-codes. Cardiovascular mortality was defined as the underlying cause of death when categorized as I00-I99. Data on hospital readmissions were obtained from hospital records.

Statistics

The results are presented as percentage and mean ± standard deviation. For continuous variables, statistical analysis was performed using Student’s unpaired t-test or the Mann–Whitney U-test for non-normally distributed variables. For discrete variables, the chi-square test was used. Cox proportional–hazard regression models analyzing time to event were built to analyze for the prediction of cardiovascular mortality. All parameters presented in have been analyzed in univariable models. Parameters with p-value ≤.25 from univariable models were included in the final multivariable model. Variables of high clinical relevance, but with p-value >.25 from univariable models, have also been tested in the multivariable model, but withdrawn if resulting in insignificant p-value, ≥.05.

In case of hospital readmissions, due to over-dispersion instead of Poisson regression, negative binomial regression models with an estimated over-dispersion factor were used. By using negative binomial regression models, we could analyze for prediction of the counted outcome, number of re-admissions. The same strategy has also been used in selecting variables for negative binomial regression models.

The final multivariable Cox model included five variables that indicates about 10 events per included variable (). Negative binomial regression models included 10 and 8 variables indicating 28 and 22 events per included variable for non-cardiovascular and cardiovascular re-hospitalizations, respectively, .

Table 2. Independent predictors of five-year cardiovascular mortality from multivariable cox proportional-hazard regression analysis.

Table 3. Independent predictors of re-hospitalizations from negative binomial regression models.

Cox models were assessed for proportional-hazard assumption for covariates graphically with adjusted log minus log curves. The hazard ratios (HR) and incidence rate ratio (IRR) with confidence intervals (CI) and p-values were presented. The PASW Statistics 18 (USA) statistical package was used for all analyses. p <.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

Cause-specific deaths and hospital readmissions

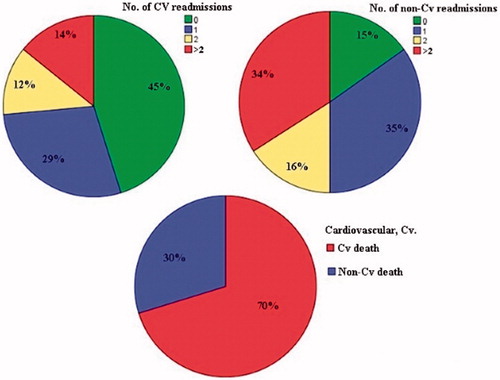

All-cause mortality 5 years after PCI was 46%. Approximately 70% of causes of deaths were cardiovascular. All-cause hospital readmissions were 71% with a total of 467 readmissions. The majority of readmissions were due to non-cardiovascular diseases (285 events), constituting 61% of all readmissions, .

Predictors of cardiovascular deaths and cause-specific re-hospitalizations

Cox proportional-hazard regression analyses for time to event for cardiovascular mortality showed female sex and culprit lesion in left coronary arteries as independent predictors of poor outcome (). Negative binomial regression models with an estimated over-dispersion factor showed female sex and complications during index hospitalization as independent predictors of an increased rate of cardiovascular re-hospitalizations, but medication with beta-blockers as an independent protective factor (). In case of non-cardiovascular re-hospitalization prior smoking was the only independent predictor of increased readmission rates (). In-hospital complications included both specific PCI-related complications and general complications including infections, acute renal failure and bleedings.

Discussion

In our study, the primary causes of deaths were cardiovascular, whereas non-cardiovascular diseases were the main reasons for hospital readmissions. Our findings are highly clinically relevant. Despite PCI, all-cause mortality is still as high as 46% over 5 years. However, according to data from the Swedish Central Bureau of Statistics, the 5-year all-cause mortality in the age group 80–89 years of the normal Swedish population during the same period (2008–2012) was about 42%. Most importantly, ∼70% of causes of deaths were cardiovascular, indicating a high potential for further cardiovascular improvement. In terms of prognostic predictors, female sex and culprit lesion in left coronary arteries were independent predictors of increased cardiovascular deaths, whereas medication with beta-blockers was an independent protective factor. It is well-known that compared to men, women have a worse prognosis after ACS.[Citation18,Citation19] Women had a higher proportion of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) compared to men. However, the regression models were adjusted for STEMI. Culprit lesion in the left side coronary arteries as a predictor of worse prognosis is not surprising, since these arteries supply the main part of the left ventricle. However, previous studies only showed increased incidence of post myocardial infarction heart failure in proximal culprit lesion compared to distally located lesions.[Citation20] Another possible mechanism is increased risk for arrhythmias.[Citation21] Complications during index hospitalization included both local complications during PCI and systemic complications; bleedings, acute renal failure and infections. These patients might not have received appropriate secondary preventive management due to a higher risk of side effects. In the case of non-cardiovascular re-hospitalizations, prior smoking was the only independent predictor of increased readmissions. Smoking-related conditions are still a major cause of mortality and morbidity.[Citation22] The common diseases which have a well-known association with smoking such as chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPD) and different malignancies were included in the regression analysis. This might indicate that these diseases are under-diagnosed in this patient group, only 12 patients (6%) had COPD and 10 patients (5.5%) had undergone lung function assessment tests. Prediction analysis for non-cardiovascular deaths was impossible due to few events.

Regarding the baseline characteristics and the outcomes, the present study is based on more comprehensive and better validated with less missing data than in any available registry databases. However, the patients in this cohort were selected for PCI on clinical bases on the discretion of the attending physician.

In summary, our study, based on our hospital cohort of ACS patients ≥80 years of age and treated with PCI, demonstrated that cardiovascular diseases were the main causes of deaths, whereas non-cardiovascular diseases were the main causes of hospital readmissions.

Disclosures statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Hamm CW, Bassand JP, Agewall S, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: the Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2999–3054.

- Van de Werf F, Bax J, Betriu A, ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG), et al. Management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with persistent ST-segment elevation: the Task Force on the Management of ST-Segment Elevation Acute Myocardial Infarction of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2909–2945.

- Wijns W, Kolh P, Danchin N, et al. Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2501–2555.

- Appleby CE, Ivanov J, Mackie K, et al. In-hospital outcomes of very elderly patients (85 years and older) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;77:634–641.

- De Boer SP, Westerhout CM, Simes RJ, et al. Mortality and morbidity reduction by primary percutaneous coronary intervention is independent of the patient's age. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3:324–331.

- Shanmugasundaram M. Percutaneous coronary intervention in elderly patients: is it beneficial? Tex Heart Inst J. 2011;38:398–403.

- Klein LW. Percutaneous coronary intervention in the elderly patient (Part I of II). J Invasive Cardiol. 2006;18:286–295.

- Thomas MP, Moscucci M, Smith DE, et al. Outcome of contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention in the elderly and the very elderly: insights from the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Cardiovascular Consortium. Clin Cardiol. 2011;34:549–554.

- Yan BP, Gurvitch R, Duffy SJ, et al. An evaluation of octogenarians undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention from the Melbourne Interventional Group registry. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2007;70:928–936.

- Munoz JC, Alonso JJ, Duran JM, et al. Coronary stent implantation in patients older than 75 years of age: clinical profile and initial and long-term (3 years) outcome. Am Heart J. 2002;143:620–626.

- Varani E, Aquilina M, Balducelli M, et al. Percutaneous coronary interventions in octogenarians: Acute and 12 month results in a large single-centre experience. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;73:449–454.

- Hiew C, Williams T, Hatton R, et al. Influence of age on long-term outcome after emergent percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Invasive Cardiol. 2010;22:273–277.

- Savonitto S, Cavallini C, Petronio AS, et al. Early aggressive versus initially conservative treatment in elderly patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:906–916.

- Tegn N, Abdelnoor M, Aaberge L, et al. Invasive versus conservative strategy in patients aged 80 years or older with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction or unstable angina pectoris (After Eighty study): an open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387:1057–1065.

- Damman P, Clayton T, Wallentin L, et al. Effects of age on long-term outcomes after a routine invasive or selective invasive strategy in patients presenting with non-ST segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: a collaborative analysis of individual data from the FRISC II–ICTUS–RITA-3 (FIR) trials. Heart. 2012;98:207–213.

- Avezum A, Makdisse M, Spencer F, et al. Impact of age on management and outcome of acute coronary syndrome: observations from the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE). Am Heart J. 2005;149:67–73.

- Henkel DM, Redfield MM, Weston SA, et al. Mode of death in patients with newly diagnosed heart failure in the general population. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10:1108–1105.

- Mehta LS, Beckie TM, DeVon HA, et al. Acute myocardial infarction in women: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation. 2016;133:916–947.

- Alfredsson J, Clayton T, Damman P, et al. Impact of an invasive strategy on 5 years outcome in men and women with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J. 2014;168:522–529.

- Antoni ML, Yiu KH, Atary JZ, et al. Distribution of culprit lesions in patients with ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction treatedwith primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Coron Artery Dis. 2011; 22:533–536.

- Gheeraert PJ, Henriques JP, De Buyzere ML, et al. Out-of-hospital ventricular fibrillation in patients with acute myocardial infarction: coronary angiographic determinants. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000; 35:144–150.

- Gutiérrez-Abejón E, Rejas-Gutiérrez J, Criado-Espegel P, et al. Smoking impact on mortality in Spain in 2012. Med Clin (Barc). 2015;145:520–525.