Abstract

Objectives. Using a patient and gender perspective, this study evaluates the experiences and perspectives of referral for paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (PSVT), and symptoms, Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL) and functional impairment before and six months after ablation. Design. This prospective study includes 214 (109 women) patients with PSVT who completed questionnaires before and after ablation addressing referral patterns, duration of arrhythmia, socioeconomic status, symptoms, HRQOL, and functional impairment. Result. Women had a longer history of symptomatic arrhythmia before ablation compared to men (16.2 ± 14.6 vs. 9.9 ± 13.1 years, p = .001). From the patient’s perspective, physicians more often incorrectly interpreted women’s symptoms as anxiety, stress, panic attacks, or depression compared to men, delaying referral for ablation. More women than men stated they were not taken seriously when consulting for their tachycardia symptoms (17% vs.7%, p = .03). At baseline, there were minor differences between the sexes in HRQOL and functional impairment, but women had a higher symptom score on Symptoms Checklist Frequency (19 vs. 14, p < .001) and Severity Scale (12 vs. 16, p = .001). At six months, women were more symptomatic and their HRQOL improved less than in men. Both sexes reported improvement in recreation and pastime (p = .001). Conclusion. Women with PSVT are referred for ablation later, and are more symptomatic before and after ablation than men. Symptoms due to PSVT are often incorrectly diagnosed as panic attacks, stress, anxiety, or depression, misdiagnoses that delay referral for ablation, especially for women.

Introduction

Catheter ablation of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (PSVT) has been used since the late 1980s. According to the ACC/AHAA/ESC guidelines from 2003 (the most recent guidelines during the period of the present study), ablation of both AV nodal re-entrant tachycardia and atrioventricular re-entrant tachycardia are classified as 1B indication [Citation1]. These recommendations state that if symptoms and the clinical history indicate that the arrhythmia is paroxysmal, and the resting 12-lead ECG gives no clue for the arrhythmia mechanism, then further diagnostic tests for documentation may not be necessary before referral for an invasive electrophysiological study and/or catheter ablation [Citation1].

Ablation of PSVT is highly successful with equally good results for both women and men [Citation2,Citation3]. PSVT may be associated with disabling symptoms such as fatigue, palpitations, dizziness, anxiety, or syncope, symptoms that negatively affect the Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL) [Citation4–6]. Women with PSVT experience more symptoms than men [Citation3,Citation7]. Despite more symptoms, women have been referred later for ablation than men, a difference that remains unexplained [Citation3,Citation7,Citation8]. However, these studies are 10 to 20 years old, and it remains unclear whether referral for ablation in patients with PSVT today differs between men and women. Furthermore, if there still is a difference, the underlying reasons have not been fully explored.

Using a patient and gender perspective, this study evaluates how patients experience their referral for ablation, their symptoms, Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL), and functional impairment before and six months after ablation.

Material and methods

Design and sample

During the period February 2013 to May 2015, 401 consecutive patients (208 women) referred to Karolinska University Hospital for a catheter ablation of PSVT, were asked to participate in the study. Demographic and clinical data and electrophysiological (EP) data were prospectively collected from the patients’ medical records. Exclusion criteria were age <18 years, previous ablations, ineligible arrhythmia diagnoses, inability to read or understand Swedish, or cognitive impairment. A delta-wave on the ECG was also an exclusion criterion, since this finding may have encouraged early ablation referral. PSVT with preexcitation during sinus rhythm is more common in men, and inclusion of these patients may have given misleading results [Citation1].

The 401 patients referred for a first ablation of PSVT were contacted by mail less than 30 days before the ablation. They were asked to participate in a prospective study regarding their experiences with ablation referral, symptoms, HRQOL, and functional impairment. The letter contained information about the purpose of the study, an informed consent form, a postage paid envelope, a folder with a questionnaire regarding the referral history, number of years with symptomatic arrhythmia, previous evaluations and diagnoses of the arrhythmia symptoms, the Swedish version of Symptom Checklist-Frequency and Severity Scale (SCL), the Swedish Medical Outcomes Short Form-36 (SF-36), and the Sickness Impact Profile (SIP). Symptom duration before ablation was defined as the time interval from the first symptoms experienced by the patients, suggesting an episode of PSVT, to the date of ablation.

Questionnaires

Referral process

During the construction of the questionnaire, six patients who had undergone catheter ablation of PSVT, were interviewed. The interviews were written down verbatim and analysed using qualitative content analysis [Citation9]. Themes found were anxiety and worries not to be believed or not to be treated politely when seeking medical help for the arrhythmias. The first version of the questionnaire was tested with a "think aloud method" on arrhythmia patients who had undergone cardioversion to help clarify the interpretation of the questions [Citation10]. Minor changes were made. The final version of the questionnaire consisted of questions that covered the described themes, symptom duration, referral history, and socioeconomic status.

The symptoms checklist: Frequency and severity (SCL)

Developed by Bubien and Jenkins, the SCL is a symptom specific instrument that measures both the frequency and severity of arrhythmia symptoms [Citation11]. The frequency scale choices are 0 to 4: never = 0; rarely = 1; sometimes = 2; often = 3; and always = 4. The severity scale choices are 1 to 3: mild = 1; moderate = 2; and extreme = 3. The two scales are summed independently. The possible range for the frequency scale is 0-64 and the possible range for the severity scale 0–48. A high total score in both scales indicates that more symptoms are experienced. The validation of the Swedish version of SCLs is ongoing. The primary data show good reliability and validity for our specific study group (Unpublished data).

The short form 36 health survey questionnaire

The HRQOL was assessed with the Swedish Short Form 36 (SF-36) survey elaborated within the framework of International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) in order to match the original US SF-36 Health Survey manual and Interpretation Guide. The Swedish version was developed by Sullivan et al. SF-36 is validated and adapted for Swedish conditions and exhibits high reliability [Citation12]. The scale evaluates eight health domains: physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional, and mental health. The scores range from 0 to 100, higher scores reflecting better functional status and well-being. Treatment of missing items and scoring was performed according to the SF-36 manual [Citation13].

The sickness impact profile

The self-rated functional capacity to perform daily activities in chronic and acute medical conditions was assessed with SIP. The instrument was developed by Bergner et al. in the United States and was translated and validated for Swedish conditions by Sullivan et al. [Citation14,Citation15]. The instrument includes 136 items that together form 12 scales. Points can be shown as total index (i.e., all 12 scales merged) for the physical and psychosocial index along with the remaining five scales or for the twelve part scales separately without compromising validity. In this study, we chose to use the following ten scales: ambulation, mobility, emotional behaviour, communication, work, sleep and rest, social interaction, alertness behaviour, home management, recreation, and pastime. The excluded items were body care and food intake. We judged these questions unfit in our specific study population, and the exclusion of the items did not affect the validity of the scale. SIP has previously been used in studies of arrhythmia patients [Citation16,Citation17].

Statistical analyses

The statistical analyses were performed using IBM corp. SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0 released 2013, Armonk, NY. AVNRT, AVRT, and focal atrial tachycardia patients were analysed together as a group. Descriptive analyses were used to describe the sample and study variables presented as mean and standard deviation or number and percent. Student’s t-test was used to compare changes in HRQOL, SIP subscales, and SCL symptom score and to evaluate differences between the sexes. Categorical variables were expressed as total number and compared between groups using the chi-squared test. To measure correlation between self-reported time with arrhythmia, education, marital status, ethnicity and occupational status, a Spearman’s correlation test was used. A p-value <.05 was considered significant.

Ethics

The investigation conforms to the principles outlined in the 2013 revised Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Regional Institutional Ethics Committee (Dnr: 2012/1390-32). The studies were performed in accordance with the international conference on Harmonization in Good Clinical Practice guidelines to protect the rights, integrity, confidentiality, and well-being of the trial subjects. All patients gave their written consent.

Results

Design and sample

Of the 401 PSVT patients contacted, 214 (53%) agreed to participate and completed the questionnaires before ablation. At the six-month follow-up, 187 (87%) of these patients completed and returned the folder with the questionnaire. There were no differences in comorbidity or anti-arrhythmic drug treatment between women and men except that hypertension was more frequent among men (p = .002) ().

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the study subjects.

Missing data

There were very few missing data from the questionnaires. One patient did not answer questions about the referral but completed the SCL, SIP, and SF-36. Regarding the SCL, six patients did not specify the severity of symptoms at baseline. No imputation was made. Only one patient did not fully complete the SF-36. This was handled according to the recommendations in the SF-36 manual. The SIP had no missing data.

Questionnaires

Referral process

Eighty-three percent of the patients were referred from specialists working in hospitals (54% from the hospitals’ outpatient clinics and 29% from the emergency departments). In 58%, the referring physician was a cardiologist. At the time of referral, only 4% of the patients were referred directly by their general practitioner. ECG documented tachycardia was available in 78% of the women and in 90% of the men (p = .03) (). More women than men were referred by female physicians (66% vs. 34%), and more men than women were referred by male physicians (39% vs. 61%) (p < .0001).

Table 2. Referral data, presented as n (%).

Symptom duration and referral history

Results from the questionnaire regarding the patient’s experience of the arrhythmia, symptom duration, and referral history are presented in and . Compared to the men, the women had a longer history of symptomatic PSVT before ablation (16.2 ± 14.6 vs. 9.9 ± 13.1 years, p = .001). Five patients (one woman and four men) had never experienced symptoms or palpitations. However, all five patients had documented tachycardia on ECG.

Table 3. Results from the questionnaire regarding the patient’s own experience of the arrhythmia, symptom duration and referral history.

Compared with men, women stated that they were more often incorrectly diagnosed or did not receive any relevant diagnoses. The general practitioners or physicians at out-patient clinics outside hospitals, compared to men, more often misdiagnosed women’s symptoms (e.g., “having palpitations is normal”) and more often indicated that women were suffering from anxiety or depression rather than tachycardia, whereas at the emergency ward women were more often diagnosed as suffering from high or low blood pressure or angina, and not tachycardia per se. In all, 23% (25/109) of the women and 11% (11/104) of the men stated that they were not believed or taken seriously when describing their tachycardia symptoms (p = .02). Furthermore, 51% (53/104) of the men stated that a correct diagnosis was made at the first consultation compared with 38% (41/109) of the women (p = .05). There was no difference regarding correct or incorrect diagnosis with respect to the consulting physician’s sex.

The reason given by the few patients who did not accept referral for ablation when first offered was that the symptoms were moderate and the arrhythmia attacks infrequent. Only one woman hesitated due to fear of complications in combination with moderate symptoms.

Socioeconomic factors

The only socioeconomic differences between the sexes were that the men had a higher income and were more often self-employed compared to the women. There was no correlation between self-reported time with arrhythmia and marital status, education, annual income, ethnicity, or occupational status (). The only correlation found was between sex and self-reported duration of arrhythmia.

Table 4. Socioeconomic data from the additional questionnaire.

Information

Seventy-two percent of the patients felt that they were well-informed and felt confident about how to act if a new arrhythmia episode should occur. Twenty-five percent of the patients wished they had been better informed ().

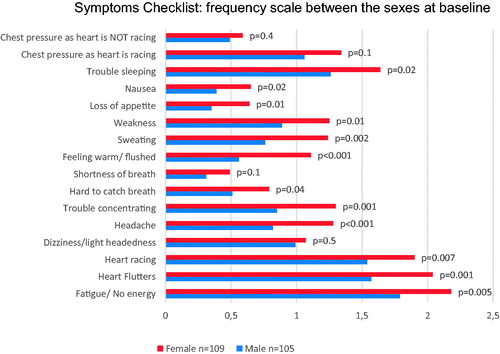

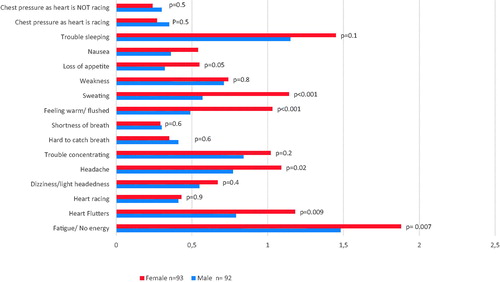

The symptoms checklist: Frequency and severity

Compared to the men, women scored higher both on the SCL Frequency scale (20 vs. 14; p < .001) and on the SCL Severity scale (16 vs. 12, p = .001) at baseline. They had more symptoms such as fatigue, heart fluttering/skipping, heart racing, headache, difficulties concentrating, difficulties breathing, feeling warm/flushed, sweating, weakness, poor appetite, and nausea. At the six-month follow-up, the frequency of the symptoms still differed between the sexes (p = .01), but there were no longer any significant differences in the severity scale (p = .1). The women still experienced more heart flutters (p = .001) and felt more fatigue (p = .005). Women also had more unspecific symptoms such as headache, sweating, and feeling warm ( and ). There were no significant differences of these unspecific symptoms when women 50 years old or younger (n = 44) were compared with women older than 50 years (n = 65).

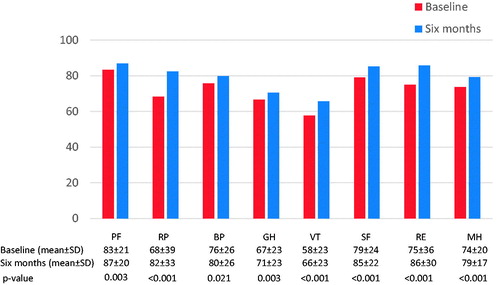

Medical outcomes short form-36

Both sexes reported lower HRQOL scores in all domains at baseline than at the six-month follow-up. The greatest improvement in scoring post ablation was seen for the items role-physical, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional, and mental health (p < .001) (). There was no difference in HRQOL when comparing the sexes at baseline, except that women scored lower than men for vitality (p = .04). At the six-month follow-up, the only difference was that women scored lower in social function than men (p = .02). Comparing the scoring for women from baseline to the six-month follow-up, there were four domains that did not improve significantly: physical functioning (p = .1), bodily pain (p = .2), social functioning (p = .1), and role-emotional (p = .1). The men improved in all domains except for bodily pain, which remained unchanged.

Sickness impact profile (SIP)

There were no significant differences between the sexes in the ten different dimensions at baseline. At the six-month follow-up, both women and men improved in the domain recreation and pastime (p = .001), but women scored lower in emotional behaviour (p = .02).

Discussion

Questionnaires

Referral process

There are significant differences between the sexes in the referral policy for ablation of PSVT. Despite more severe symptoms, women are referred for ablation later than men. From the patients’ perspective, this seems to be a doctor’s delay; women with a history of PSVT consulting physicians are more often incorrectly diagnosed than men are and consequently are offered ablation later than men are. Regardless of sex, the duration of symptomatic PSVT is still very long before curative ablation is offered. Furthermore, this study shows that men improve more after ablation than women do, as judged by HRQOL and with respect to symptom and functional impairment, even though the success rate of ablation is similar.

Gender differences

Earlier studies have reported longer duration of symptoms for women compared to men with respect to PSVT. A study by Dagres et al. (2003) covering 894 patients during a 43-month period found that women had symptomatic PSVT longer than men before ablation – 15.4 vs.13.1 years [Citation3]. Wood et al. reported the same finding in a study of 52 patients (34 women) [Citation4]. The mean duration of symptomatic tachycardia for men was 11 years vs. 14 years for women [Citation4]. At our own institution, Braunschweig et al. evaluated 318 patients with PSVT undergoing a transoesophageal EP study between 1990 and 2007 [Citation18]. Durations of symptoms for men and women were 13 and 17 years, respectively.

Although ablation today is a well-established treatment for patients with symptomatic PSVT, women were still referred much later for ablation than men after they had experienced their first episode of tachycardia, despite more symptoms. Dagres et al. (2003) suggested that one reason women wait longer for ablation may be that women are more hesitant to undergo this procedure, and doctors more hesitant to recommend this therapy due to the possible adverse effects of radiation exposure on the female reproductive function [Citation3]; however, we did not find any support for this. In our study, 84% of both men and women accepted referral for ablation when first offered.

One explanation why women with PSVT are referred later for ablation, appears to be a difficulty in correctly interpreting symptoms in women. More women than men stated that they were not taken seriously when consulting physicians and health care providers for their arrhythmia. Women with PSVT were more often incorrectly diagnosed as suffering from anxiety, depression, or social stress. Fewer women than men believed they had been correctly diagnosed at their first consultation.

Previous reports support our finding that women with PSVT are more often incorrectly diagnosed compared with men [Citation7]. Lessmeier et al. (1997) suggested that women with arrhythmia symptoms often are diagnosed as suffering from stress, panic attacks, or anxiety [Citation8]. Women who experience tachycardia episodes, were more often incorrectly diagnosed with psychiatric symptoms. Dagres et al. (2003) also suggested that women are more concerned about the safety of the ablation procedure, and that they tolerate the incapacitation of the arrhythmia better than men [Citation3]; however, these findings are not supported by our findings. In our study, only one woman hesitated due to minor symptoms and fear of complications. Furthermore, in our study the women were more symptomatic and had a lower HRQOL than the men.

It should also be noted, however, that a contributing factor for longer referral times for women could be that women, despite being more symptomatic, endure their arrhythmia longer and consult a doctor later than men, (i.e., patient’s delay). We do not have reliable data regarding the patients’ first contact with their doctor due to their arrhythmia in relation to the first experienced episode. However, we found that women tended to consult doctors more often for their arrhythmia than men, before referral for ablation. This finding supports the conclusion that doctor’s delay is of importance.

ECG confirmation of tachycardia

The number of patients who had a documented ECG recording of their index tachycardia at the time of referral is remarkably high – 78% in women and 90% in men. It is reasonable to assume that many physicians do not refer a patient with PSVT for ablation without an ECG confirming the diagnosis, a confirmation strategy that is not part of the ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines. These guidelines state that if a patient exhibits typical symptoms and has a resting 12-lead ECG without evidence of arrhythmia mechanism, then further diagnostic tests for documentation may not be necessary before referral for catheter ablation [Citation1]. In patients with infrequent tachycardia, recording the tachycardia on ECG is notoriously difficult and may contribute to the delayed referral. However, the clinical picture in patients with PSVT is often quite characteristic with a sudden onset and often a sudden termination of symptoms. Furthermore, the patient has often been able not only to distinguish the heart rate as fast and highly regular, but can also often report the exact heart rate during the attacks. It is not uncommon that the patient has learned to terminate the tachycardia with a vagal manoeuvre [Citation7]. One may therefore argue that with a typical case history, a diagnosis of PSVT is highly probable, and ECG documentation not always necessary. One explanation for the remarkably long delay from first experienced tachycardia until ablation may be a demand for ECG proof before referral. Furthermore, this demand may also help explain why women wait longer for referral, as we found that women less often than men had a confirmed ECG diagnosis.

Referring physicians

We found that the patient’s GP seldom referred the patient for ablation. Similarly, Wood et al. (2007) found that the primary care physicians misinterpreted the patients’ symptoms and consequently did not refer them to a cardiologist or electrophysiologist [Citation7]. They also describe the patients’ disappointment and frustration when an episode of PSVT abruptly ended before it was documented on an ECG.

In our study, female physicians more often referred women than men for ablation, whereas male physicians more often referred men than women for ablation. It is not possible to determine whether this finding reflects a genuine difference in the evaluation of the patients’ symptoms or the patients’ preference for a female or a male physician.

Information

Twenty-five percent of the study group wished that they had been provided with better information about arrhythmias, treatment options, and how to handle tachycardia episodes in daily life. Lane et al. (2015) has suggested that a structured educational program addressing the quality of life, misperceptions of the disease, and treatment effects might help patients with PSVT [Citation6].

The symptoms checklist: Frequency and severity scale and SF-36

We found an improvement regarding symptom and HRQOL after ablation, but the women did not improve as much as the men. Similar results have been described in other reports [Citation11,Citation19]. The women in our study were more symptomatic and experienced more heart flutters, felt more fatigue, and exhibited more unspecific symptoms than the men at baseline and at the follow-up. Post-menopausal symptoms could be a confounding factor in this respect. However, comparing women 50 years or younger with those older than 50 years did not show any differences regarding unspecific symptoms such as headache, sweating, and feeling warm.

Wood et al. (2010) found that patients experienced heart flutters and heart skipping during the initial few weeks after RF-ablation, but the study did not report whether these symptoms differed between women and men [Citation4]. These symptoms are usually caused by supraventricular premature beats and the clinical experience is that symptomatic premature beats diminish gradually during the first six months after ablation. However, since women are more symptomatic to tachycardia per se, it is reasonable to assume that they also experience more symptoms due to premature beats after ablation [Citation3,Citation20].

At the six-month follow-up, both the SF-36 and SIP showed less improvement in the role emotional scales in both women and men. The role emotional item addresses issues like “difficulties performing the work or other activities” or “accomplished less than you would like”. However, it is unclear why the role emotional items remain an issue after cardiac ablation.

Limitations

Our results may suffer from selection bias. It is reasonable to expect that the patients who accepted to participate in the study were more motivated than those who did not, which may correlate to more symptoms before the referral. Compared with previous reports from our institution mean age, sex distribution and comorbidities are similar in the present report [Citation21–23]. In addition, we do not know whether the improvement in the HRQOL and reduction of symptoms are exclusively due to the catheter ablation or whether a reduction of antiarrhythmic drugs contributes. Finally, which we want to emphasize, we only capture the patients’ experiences of their medical consultations before the actual referral for ablation and not their physicians’ experiences.

Conclusion

Women with PSVT are referred for ablation later, and are more symptomatic before and after ablation than men. From the patients’ perspective, symptoms due to PSVT are often incorrectly diagnosed as panic attacks, stress, anxiety, or depression, diagnoses that delay referral for ablation, especially for women. Once a correct diagnosis has been made, there is no sex difference regarding recommendation of ablation.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by the Women and Health Foundation, the 1.6 Million Club, funds from the Heart and Vascular Theme at Karolinska University Hospital, and The Swedish Heart and Lung Association.

References

- Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Scheinman MM, Aliot EM, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias–executive summary. a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on practice guidelines and the European society of cardiology committee for practice guidelines (writing committee to develop guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias) developed in collaboration with NASPE-Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1493–1531.

- Sohinki D, Obel OA. Current trends in supraventricular tachycardia management. Ochsner J. 2014;14:586–595.

- Dagres N, Clague JR, Breithardt G, et al. Significant gender-related differences in radiofrequency catheter ablation therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1103–1107.

- Wood KA, Stewart AL, Drew BJ, et al. Patient perception of symptoms and quality of life following ablation in patients with supraventricular tachycardia. Heart Lung. 2010;39:12–20.

- Meissner A, Stifoudi I, Weismüller P, et al. Sustained high quality of life in a 5-year long term follow-up after successful ablation for supra-ventricular tachycardia. Results from a large retrospective patient cohort. Int J Med Sci. 2009;6:28–36.

- Lane DA, Aguinga L, Blomström-Lundqvist C, et al. Cardiac tachyarrhythmias and patient values and preferences for their management: the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) consensus document endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), and Sociedad Latinoamericana de Estimulacion Cardiaca y Electrofisiologia (SOLEACE). Europace. 2015;17:1747–1769.

- Wood KA, Wiener CL, Kayser-Jones J. Supraventricular tachycardia and the struggle to be believed. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2007;6:293–302.

- Lessmeier TJ, Gamperling D, Johnson-Liddon V, et al. Unrecognized paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia. Potential for misdiagnosis as panic disorder. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:537–543.

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24:105–112.

- Someren MV, Barnard YF, Sandberg JAC. The think aloud method: a practical guide to modelling cognitive processes. London (UK): Academic Press; 1994.

- Bubien RS, et al. Effect of radiofrequency catheter ablation on health-related quality of life and activities of daily living in patients with recurrent arrhythmias. Circulation. 1996;94:1585–1591.

- Sullivan M, Karlsson J, Ware JE, Jr., The Swedish SF-36 Health Survey–I. Evaluation of data quality, scaling assumptions, reliability and construct validity across general populations in Sweden. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41:1349–1358.

- Sullivan M, Karlsson J, Ware JE, et al. Swedish manual and interpretation guide. 2nd ed. Gothenburg: Sahlgrenska University Hospital; 2002.

- Bergner M, Bobbitt RA, Carter WB, et al. The sickness impact profile: development and final revision of a health status measure. Med Care. 1981;19:787–805.

- Sullivan M, Ahlmen M, Archenholtz B, et al. Measuring health in rheumatic disorders by means of a Swedish version of the sickness impact profile. Results from a population study. Scand J Rheumatol. 1986;15:193–200.

- Lim KT, Davis MJ, Powell A, et al. Ablate and pace strategy for atrial fibrillation: long-term outcome of AIRCRAFT trial. Europace. 2007;9:498–505.

- Sweeney MO, Hellkamp AS, Ellenbogen KA, et al. Prospective randomized study of mode switching in a clinical trial of pacemaker therapy for sinus node dysfunction. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2004;15:153–160.

- Braunschweig F, Christel P, Jensen-Urstad M, et al. Paroxysmal regular supraventricular tachycardia: the diagnostic accuracy of the transesophageal ventriculo-atrial interval. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2011;16:327–335.

- Walfridsson U, Walfridsson H, Arestedt K, et al. Impact of radiofrequency ablation on health-related quality of life in patients with paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia compared with a norm population one year after treatment. Heart Lung. 2011;40:405–411.

- Farkowski MM, Pytkowski M, Maciag A, et al. Gender-related differences in outcomes and resource utilization in patients undergoing radiofrequency ablation of supraventricular tachycardia: results from Patients’ Perspective on Radiofrequency Catheter Ablation of AVRT and AVNRT Study. Europace. 2014;16:1821–1827.

- Insulander P, Bastani H, Braunschweig F, et al. Cryoablation of substrates adjacent to the atrioventricular node: acute and long-term safety of 1303 ablation procedures. Europace. 2014;16:271–276.

- Insulander P, Bastani H, Braunschweig F, et al. Cryoablation of atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia: 7-year follow-up in 515 patients-confirmed safety but very late recurrences occur. Europace 2017;19:1038–1042.

- Bastani H, Insulander P, Schwieler J, et al. Safety and efficacy of cryoablation of atrial tachycardia with high risk of ablation-related injuries. Europace. 2009;11:625–629.