Abstract

Aim. Barriers to participation in cardiac rehabilitation (CR) may occur at three levels of the referral process (lack of information, declining to participate, and referral to appropriate CR programme). The aim is to analyse the impact of socioeconomic status on barriers to CR and investigate whether such barriers influenced the choice of referral. Methods. The Rehab-North Register, a cross-sectional study, enrolled 5455 patients hospitalised at Aalborg University Hospital with myocardial infarction (MI) during 2011-2014. Patients hospitalised with ST-elevated MI and complicated non-ST-elevated MI were to be sent to specialized CR, whereas patients with uncomplicated non-ST-elevated MI and unstable angina pectoris were to be sent to community-based CR. Detailed selected socioeconomic information was gathered from statistical registries in Statistics Denmark. Data was assessed using logistic regression. Results. Patients being retired, low educated, and/or with an annual gross income <27.000 Euro/yr were significantly less informed about cardiac rehabilitation programmes. Patients being older than 70 years, retired, low educated and/or with an annual gross income <27.000 Euro were significantly less willing to participate in CR. Further, this patient population were to a higher extent referred to community-based CR. Conclusion. Patients with low socioeconomic status received less information about and were less willing to participate in cardiac rehabilitation. The same patient population was to a higher extent referred to community-based CR. Knowledge about barriers at different levels and the impact of social inequality may help in tailoring a better approach in the referral process to CR.

Introduction

Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) is important for improving the prognosis following ischemic heart disease. The known benefits of participation in CR include reduced mortality, symptom relief, smoking cessation, improved physical fitness, improved psychosocial well-being, and overall risk factor modification [Citation1]. Non-attenders in CR are often older, female [Citation2], with low socioeconomic status, and with increased risk factors [Citation3]. Further, studies have identified some predictors for non-referral [Citation4–8], including older age, female sex, and low socioeconomic status. Research suggests that barriers to referral and participation in CR include, e.g., lack of transport, financial cost, misunderstanding the reason for participation, and embarrassment [Citation9].

In Denmark, CR is considered an integral part of treatment of patients with ischemic heart disease [Citation10,Citation11].

It is challenging to recruit and motivate people to participate in CR and this combined with a continuously high dropout rate has led to an increased attention to possible barriers to the use of health care services and the inhomogeneity of its users. Barriers to participation in CR may occur at three levels of the referral process (lack of information, declining to participate, and referral to appropriate CR programme). It is unclear to what extend and at which levels in the referral process social inequality influences or predicts failure to engage in CR.

We created the Rehab-North Register from questionnaires administered to all patients first time admitted to Aalborg University hospital with a diagnosis of ischemic heart disease in the period 2011-2014. The aim of this paper was to analyse the impact of socioeconomic status on barriers to CR at different levels of the referral process on patient in the Rehab North Register. Further, we wished to analyse differences in socioeconomic characteristics on the population referred to a specialized CR compared to those referred to community-based CR.

Methods

Settings and study design

The Rehab-North Register is based on a cross-sectional study of patients hospitalized at the Department of Cardiology, Aalborg University Hospital with first time myocardial infarction in the period of 2011–2014.

Study population

Patients hospitalized with ST-elevated myocardial infarction (STEMI), non-ST-elevated myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), unstable angina pectoris (UAP) or angina pectoris (AP) are assessed for CR before discharge. Guidelines at Aalborg University Hospital recommend patients with STEMI and complicated NSTEMI to be referred to specialized CR. Patients with uncomplicated NSTEMI, UAP, or patients who received elective coronary angiography or percutaneous cardiac intervention, are referred to community-based CR. Cardiac rehabilitation nurses inform the patients about cardiac rehabilitation and doctors are in charge of the referral to the specific rehabilitation programme. Patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting is informed about cardiac rehabilitation at the Thoracic Surgery Department performing the operation.

The Rehab-North Register consists of patients identified from a questionnaire assessing CR eligibility during hospitalization. The questionnaire assessed whether patients were informed about CR, if patients wished to participate in CR, and which programme patients were referred to (specialized CR or community-based CR). To be eligible, patients had to suffer from ischemic heart disease with the diagnoses of STEMI [ICD-10: I21.0, I21.1, I21.3], NSTEMI [ICD-10: I21.4], UAP [ICD-10: I20.0] or AP [ICD-10: I20.1, I20.8, I20.9, I25.1], and be hospitalized in the period from 01.01.2011 through 31.12.2014. If the patient had non-ischemic heart disease as primary diagnosis, we searched secondary diagnoses to find possible ischemic heart disease diagnoses. The diagnoses were identified by linkage with the Danish National Patient Register. The questionnaires were introduced at the department in 2009. We defined the run-in period from 2009- to 2010 to achieve the most reliable material. One author extracted data from the questionnaires. If patients had more than one hospitalisation due to cardiac disease, we only included the first hospitalisation. If patients had more than one questionnaire linked to the same hospitalisation date, we used the one best filled out. Finally, patients with missing cardiac rehabilitation programme were excluded.

Register data sources from Statistics Denmark

Registers from Statistics Denmark were linked to the Rehab-North Register to reduce missing values. The registers provided diagnoses and socioeconomic information of the population. Data sources were linked with population registers using the unique 10-digit personal identification number (CPR number) that is assigned to all Danish residents at birth or upon immigration. This CPR number enables highly valid and cost effective individual-level record linkage of data between Danish registers. All used registers have previously been described [Citation12–15].

The Danish Civil Registration System provided data on the civil status [Citation12].

The Danish National Patient Register provided diagnoses to the study participants [Citation13]. Diagnoses were classified according to the International Classification of Disease, 10th revision.

The Student Register identifies each student’s educational career. The educational level is categorized into three levels according to Statistic Denmark’s classification system: higher education (university, medium length education including bachelor degree), medium education (high school, trade/craft education and short education), and low education (obligatory schooling) [Citation14].

The Income Statistics Register described the income composition of the Danish population. For this study, the register provided income data at a personal level [Citation15].

Definition of socioeconomic status:

Socioeconomic factors included civil status (married/registered partnership, divorced/annulled partnership, widowed/longest living partner, or unmarried), labour status (employed, unemployed, or retired), educational level (low, medium, or high education), and yearly gross income in Euro. Comorbidity is defined as diagnosis stated in Charlson Comorbidity Index, but only from the year 2011 until hospitalisation. Other important factors may be associated with socioeconomic status, but is not taken into account in this study.

Outcome measures

Barriers to CR were measured at two levels: lack of information and unwillingness to participate. This study analyses the impact of socioeconomic status on barriers to CR and investigates whether such barriers influenced the choice of referral despite the fact that referral should be based on the complexity of the disease.

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics and logistic regression were used to describe the population of the Rehab-North Register. Methods such as proportions and means were used to summarize data. Logistic regression analysis of odds of the different referrals was performed using Stata Software (v. 11.1; Stata Corp. College Station, TX). All odds ratios are based on univariate analyses. One category was chosen as reference and results are presented as odds ratios to the reference. When compared with the reference group, an odds ratio greater/lower than 1 estimates the association of outcome being higher/lower in the presence of a given exposure, e.g. information of CR. Data were systematically collected from CR questionnaires with EpiData Software (v. 2.0.5.51 EpiData Association, Denmark).

Ethics

The Danish Data Protection agency (project number: 2008-58-0028) and the Danish Patient Safety Authority (project number: 3-3013-1429/1) approved the study. No written consent is needed for use of such data in Denmark.

Results

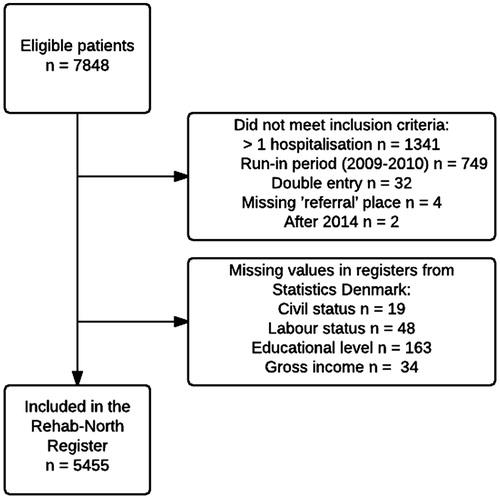

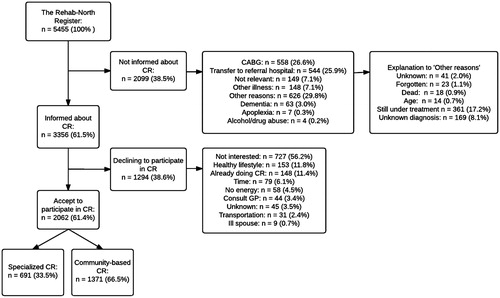

In total, 2393 patients were excluded from the study as they did not meet the inclusion criteria or had missing socioeconomic data, leaving a total study population of 5455 patients (). The flow through the referral process for the population included in the Rehab-North Register is depictured in . These data were obtained from questionnaires.

Figure 2. Flowchart of patients included in the Rehab-North Register. CR: cardiac rehabilitation: CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; GP: general practitioner.

Baseline socioeconomic characteristics overall and stratified by type of ischemic heart diagnosis is shown in . Overall, the population had a mean age of 67.3 years and approximately 69.7% were men. The majority of patients were married (64.4%), and either retired (67.8%) or currently employed (29.1%), while only a minority of patients had a higher education (12.6%). Similar baseline characteristics were observed when stratifying the population on type of ischemic heart disease.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics.

Patient characteristics and barriers to information about cardiac rehabilitation

A total of 3356 (61.5%) patients received information about CR. For each uninformed patient, the nurse noted reasons for this decision – these reasons symbolize system-level barriers to CR (). The three most common reasons were scheduled ‘coronary artery bypass grafting’ (26.6%), ‘transfer to referral hospital’ (25.9%), and ‘other reasons’ (29.8%). The comparison of informed and non-informed patients showed clear differences with regard to socioeconomic factors (). The odds for information were highest for people aged <50–59 years. The odds of information were 47% lower if widowed/longest living partner compared with married/in partnership. Regarding labour status, people being retired had significantly lower odds of information compared with those still in the working force.

Table 2. Informed about cardiac rehabilitation.

Odds of information were significantly lower for patients with low compared to medium or higher level of education. A clear trend in gross income was observed concerning information about CR. A gross income above 27,000 Euro resulted in a significant increase in odds of information about CR. Finally, no comorbidity significantly increased the odds of information compared with 1-2 comorbidities.

Patient characteristics and barriers to willingness to participate in cardiac rehabilitation

shows characteristics of patients by willingness to participate in CR.

Table 3. Wish to participate in cardiac rehabilitation.

Of the 3356 informed patients, 2062 (61.4%) chose to accept the offer of CR, while 1294 (38.6%) declined – the reasons for declining are categorized as patient-level barriers to CR ().

The three most common reasons for declining CR were ‘not interested’ (56.2%), ‘healthy lifestyle’ (11.8%) and ‘already doing a CR programme’ (11.4%).

The wish to participate in CR showed differences with regard to socioeconomic factors (). The odds for wish to participate were highest for people aged <50 years. Unmarried people had a significantly higher wish to participate. Being retired significantly lowered the odds for wishing to participate. Higher educational level increased the willingness to participate in CR. Gross income above 27,000 Euro per year significantly increased the odds of willingness to participate. Having 1-2 comorbidity increased the odds of willingness to participate with 37%.

Characteristics of patients referred to specialized or community-based cardiac rehabilitation

shows characteristics of patients referred to specialized compared with community-based CR. The 2062 patients who accepted the offer of CR were, depending on their diagnosis and clinical status, sent to either specialized CR (691 (33.5%) patients) or community-based CR (1371 (66.5%) patients). Males were to a significantly much higher degree referred to specialized CR. Being under 59 years of age increased the odds of specialized CR compared with older patients. Regarding civil status, widows had a 54% lower odds of being referred to specialized CR. Further, retired patients also had a significant lower odds of referral to specialized CR compared with patients still working. Having a medium-length or high education significantly increased the odds of referral to specialized CR. Similarly, a gross income above 40,500 significantly increased the odds compared with patients with lower incomes. Comorbidities did not influence the place of referral.

Table 4. Characteristics of patients referred to CR.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, we wished to investigate the impact of social inequality on barriers to the referral process of CR. Our principal findings were that patients with lower socioeconomic status were overrepresented among those not informed about CR and among those who declined to participate in rehabilitation. The same patient population were to a higher extent referred to community-based CR. A total of 61.4% of the informed patients wished to participate in CR and were referred to a CR programme after hospital discharge. This is in accordance with earlier findings, showing that 56%-86% of the eligible patients were referred to CR [Citation4,Citation16].

Barriers to CR

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the referral process of ischemic heart patients to CR and investigate the influence of social inequality on barriers to such programmes. We sought to split the cardiac referral process into ‘information about CR, ‘wish to participate in CR’ and ‘referral to CR’ and hereby identify barriers at different levels with focus on social inequality.

The arguments for not informing some patients seemed well-reasoned (). However, it is interesting that patients with low socioeconomic characteristics to a higher degree were put into these categories. The question is, if health care workers subconsciously are more prone to categorise these patients into categories not able to undergo a CR programme – thus performing system-level barrier to CR.

‘Coronary artery bypass graft’ and ‘transfer to referral hospital’ are considered well-founded reasons not to inform the patients about CR, as patients receive information about CR at other cardiology departments. Unfortunately, these patients are lost to follow-up in this study, and we have not received any confirmation regarding referral to CR. The patient-level barriers indicated a continuous need to improve the referral rate to CR, as 56.2% stated ‘not interested’ as their main reason for their nonparticipation in CR. Obtaining thorough information about socioeconomic factors may be an important first step in identifying patients with lower socioeconomic status, who may be targeted for tailored motivation strategies regarding participation in CR. The existence of national guidelines and devoted health care workers may explain the remarkably high percentage of STEMI patients who wished to participate in CR (17% vs. 2.2%). The explanation for a lower willingness to participate in CR among patients with angina pectoris and unstable angina pectoris is multi-causal, but studies find that the health care workers’ attitude towards CR programmes is a clear predictor of referral [Citation7,Citation9,Citation16,Citation17].

Referral to either a specialized or community-based CR programme seemed to be under influence by socioeconomic status as patients with high socioeconomic status to a higher extent were referred to specialised CR. More data are needed to estimate if the patients were given a correct referral to a given CR programme or if system-level barriers were present at this level of the referral process.

Gender differences in referral to CR

Despite knowledge of an increasing proportion of female myocardial infarction patients, research has documented that women were less often referred to CR – likely because of a cluster of predictors such as: higher age, greater co-morbidity, higher depression, lower initial exercise capacity, and less available social support [Citation5,Citation17,Citation18]. We found no gender differences in information about and willingness to participate in a CR programme. However, women were more likely to be referred to a community-based CR programme. It should be noted, that our study had noticeably larger percentages of informed/referred patients compared with another international study [Citation5] but in accordance with a national study [Citation16].

The Rehab-North Register addressed barriers in the process from hospital admission to referral status. Whether patients actually participated in rehabilitation, which programme they were finally enrolled in and subsequent adherence to the rehabilitation programme are subject to further analyses. Moreover, since CR programmes are to be an exclusive community task in the North Denmark Region, future studies also based on the Rehab-North Register will address if participation in either a specialized or community-based CR programme translates into differences in clinical outcomes.

Study limitations

Firstly, the presence of missing values as data were collected for administrative purposes rather than for scientific research. Therefore, some questionnaires lacked specified reasons for ‘no information about CR’ and ‘no wish to participate in CR’. Incorrect registration may have appeared, but this is unlikely to have influenced the overall results, as it would likely be independent of the referral process. Further, the large sample size curtailed the influence of random variation in the study. Patients’ use of medication was not included. The use of administrative registers to identify socioeconomic factors allowed us to estimate its influence on the referral process of CR. All registers have previously been described, and socioeconomic factors generally have a high validity in Danish nationwide registers [Citation12–15]. The use of gross income, educational level and occupational status must be acknowledged as being highly correlated when using them as measures of socioeconomic differences. Multivariable analyses could assess this issue but it would be difficult to interpret as the estimates most often are related in a causal relation. When interpreting the results in , this must be taken into account, as the analyses only contain univariate associations.

Conclusion

In the present study, patients with low socioeconomic status were more likely not to receive information about CR. The same patient population were to a higher extent referred to community-based CR. Barriers existed at patient and system levels and showed that social inequality still interferes with the referral process. Knowledge about barriers at different levels and the impact of social inequality may help in tailoring a better approach in the referral process to CR.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Laukkanen JA. Cardiac rehabilitation: why is it an underused therapy? Eur Heart J. 2015;36:1500–1501.

- Witt BJ, Jacobsen SJ, Weston SA, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation after myocardial infarction in the community. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:988–996.

- Nielsen KM, Faergeman O, Foldspang A, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation: health characteristics and socio-economic status among those who do not attend. Eur J Public Health. 2008;18:479–483.

- Brown TM, Hernandez AF, Bittner V, et al. Predictors of cardiac rehabilitation referral in coronary artery disease patients. Findings from the American Heart Association’s Get with the Guidelines Program. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:515–521.

- Colbert JD, Martin B-J, Haykowsky MJ, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation referral, attendance and mortality in women. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2015;22:979–986.

- Shanmugasegaram S, Oh P, Reid RD, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation barriers by rurality and socioeconomic status: a cross-sectional study. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12:72–78.

- De Vos C, Li X, Vlen I, et al. Participating or not in a cardiac rehabilitation programme: factors influencing a patient’s decision. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2013;20:341–348.

- Dahhan A, Maddox WR, Krothapalli S, et al. Education of physicians and implementation of a formal referral system can improve cardiac rehabilitation referral and participation rates after percutaneous coronary intervention. Hear Lung Circ. 2015;24:806–816.

- Neubeck L, Freedman SB, Clark AM, et al. Participating in cardiac rehabilitation: a systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative data. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2012;19:494–503.

- Netvaerk af forebyggende sygehuse i Danmark. Hjerterehabilitering på danske sygehuse. Hjerterehabilitering på danske sygehuse. 2004.

- Available drom: http://nbv.cardio.dk/hjerterehabilitering. 29. Hjerterehabilitering; 2014. p. 1–7.

- Pedersen CB. The Danish Civil registration system. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39;22–25.

- Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39;30–33.

- Statistics Denmark. Documentation of statistics for The Student Register 2015; 2015.

- Baadsgaard M, Quitzau J. Danish registers on personal income and transfer payments. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:103–105.

- Meillier LK, Nielsen KM, Larsen FB, et al. Socially differentiated cardiac rehabilitation: Can we improve referral, attendance and adherence among patients with first myocardial infarction? Scand J Public Health. 2012;40:286–293.

- Jackson L, Leclerc J, Erskine Y, et al. Getting the most out of cardiac rehabilitation: a review of referral and adherence predictors. Heart. 2005;91:10–14.

- Pouche M, Ruidavets J-B, Ferrières J, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation and 5-year mortality after acute coronary syndromes: The 2005 French FAST-MI study. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2016;109:178–187.