Abstract

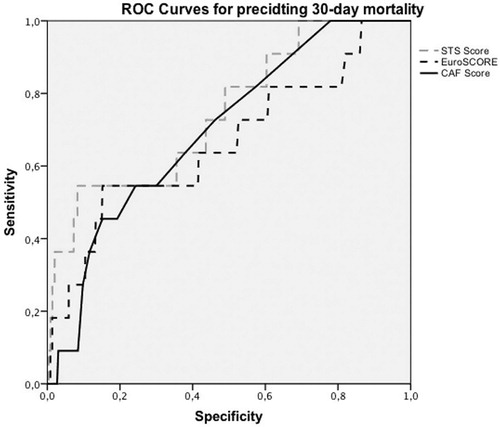

Objectives. Typically, patients referred to cardiac surgery are aged. Because EuroSCORE tend to overestimate and STS tend to underestimate the risk of mortality after cardiac surgery, frailty has become interesting as a potential predictor for mortality after cardiac surgery. Therefore, we conducted a study to identify the number of frail patients undergoing cardiac surgery and describe the risk of short-term complications and mortality. Design. In a prospective observational study, we have compared the surgical outcome in frail versus non-frail patients. Patients aged > 65 years and undergoing non-acute cardiac surgery were included. Frailty was assessed using the comprehensive assessment of frailty (CAF) score. The CAF evaluates the patient’s physical condition through performing physical tests. Results. 604 patients included, 477 were men and the median age was 73 years (range, 65–90). Twenty-five percent were deemed frail. Frail patients had a four times higher 30-day mortality. Furthermore, frail patients had higher postoperative complication rates of atrial fibrillation, prolonged ventilation, re-operations, renal failure, transfusion requirements, and increased length of stay. Patients who died within 30 days had a significantly higher CAF score than those who survived (p = .039). Based on ROC curves, the area under the curve (AUC) for CAF score was 0.700, EuroSCORE 0.664 and STS score 0.748. Conclusion. Frailty is common in patients undergoing cardiac surgery and carries increased risk of 30-day mortality and postoperative complications. The AUC indicates similar prediction of mortality for CAF score compared to the existing risk scores.

Clinical Trials Registration ID: NCT02992587

Introduction

In general, patients referred to cardiac surgery are growing older and more fragile with an increasing number of patients now being 65 years of age or older [Citation1]. This aging population of patients undergoing cardiac surgery often has several comorbidities and has an increased risk of complications and mortality compared to younger patients [Citation2,Citation3]. However, studies indicate that elderly patients continue to benefit from cardiac surgery in terms of increased quality of life, relief of symptoms, low incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events, and increased survival [Citation4]. On the other hand, studies have also shown that elderly patients with cardiovascular diseases might be frailer. Frailty is a term used to assess the biological status of a patient and is defined as an impaired resistance to stressors due to a decline in physiologic reserve [Citation4–9].

Cardiac surgery risk scores are used to assess 30-day mortality in clinical evaluation before surgery. The most common risk scores are the European system for cardiac operative risk evaluation (EuroSCORE) and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) score. However, the EuroSCORE seems to tend to overestimate the perioperative risk in the elderly population, while the STS score tends to underestimate the risk [Citation10,Citation11]. One of the reasons for this might be that none of the risk scores incorporate the biological status of the patients [Citation12–14].

Within the last 10 years, a few studies evaluating different ‘frailty scores’ in cardiac patients have been published [Citation4–7,Citation9,Citation15–22]. None of these frailty risk scores are fully validated and, therefore, have not been widely adopted. In a single-center study of 400 patients undergoing elective cardiac surgery and aged 74 or above, frailty was assessed by the comprehensive assessment of frailty (CAF) score. The CAF scores assess weakness, self-reported exhaustion, a decrease in gait speed, activity levels, and physical performance [Citation17,Citation18]. The CAF score showed good correlation with the EuroSCORE and STS score and is easy to perform for the patient and the staff [Citation18].

To validate the CAF score in a Danish cohort of patients, a study was conducted to identify and describe the number of frail patients undergoing first-time non-urgent cardiac surgery and to compare the risk of short-term complications in frail versus non-frail patients.

We hypothesized that patients deemed frail using the CAF score had increased risk of short-term complications. Furthermore, it was expected that the frailty score in addition to the EuroSCORE or STS score, better predicts the risk of complications compared to the EuroSCORE or STS scores alone.

Materials and methods

Study design

The study was designed as a single-center prospective observational study at the Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen University Hospital, Denmark. To evaluate frailty, we used the CAF scoring scale [Citation18]. This is based on a combination of different scoring scales. The first part is based on the Fried criteria [Citation23]: weight loss, self-reported exhaustion, low activity, decreased gait speed, and weakness. The CAF scoring scale includes all except weight loss. Self-reported exhaustion is addressed by two questions by the original Center for epidemiological study Depression (CES-D) scale [Citation24]. Low activity was assessed by asking about the instrumental activity of daily living (IADL) [Citation25], including walking, housework, outdoor activity, regular sport, and others. Following this registration, kilocalories per week were calculated by the formula: kcal = (w × frequency of activity × duration of activity)/2. The ‘w’ variable is dependent on the type of activity. Slowness was measured as speed in meters per second, where the patient walks 4 m at normal walking speed, and weakness through grip strength by pulling the grasp of a dynamometer as strong as possible (reported in kg).

The second part is the physical performance tests. Balance was assessed by testing how long the participant can stand still with their feet together, with one foot halfway in front of the other (semi-tandem) and with one foot completely in front of the other one (tandem). The duration of each position is registered in a frailty table to score points. In the last balance test, the act of turning around 360 degrees is registered and scored in the frailty table. Body control is tested by the following: get up and down from a chair three times, put on and remove a jacket, and pick up a pen from the floor.

The last part involves laboratory tests, including the level of serum albumin, creatinine, and a lung function test for calculation of Forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1). Ultimately, two physicians, one cardiac surgeon, and one other clinician at the department estimated the patient’s frailty after the Clinical Frailty Scale score [Citation18].

The clinical frailty scale is derived from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging, and is based on a frailty index composed of 70 items estimating the frailty on a scale from 1 to 7. A total CAF score is composed of adding the individual test scores and has a maximum score of 35 points, divided in ‘not frail’ (points 1–10), ‘moderately frail’ (points 11–25), and ‘severely frail’ (points 26–35). As very few patients in our study were deemed severely frail. We have merged moderately and severely frail into one group, named ‘frail’.

Patients

A total of 604 patients were enrolled during February 2016 and January 2018. Inclusion criteria were: patients aged 65 years or above, referral to elective or subacute cardiac surgery, and undergoing CABG, valve replacement/repair, or CABG with valve replacement/repair. Exclusion criteria were: emergency surgery, clinically unstable patients, severe neuropsychiatric impairment, no cooperation (psychiatric diagnosis), and re-operation.

Outcome measures

Here, we report the 30-day outcome measures for the study:

All-cause mortality (hospital mortality or death within 30 days postoperatively)

Major Adverse Cardiac and Cerebrovascular Events (MACCE), acute myocardial infarction, stroke, and mortality

Postoperative complications, such as renal failure, defined from the RIFLE criteria (three times increased creatinine in 48 h, creatinine above 350 µmol/L, acute rise of >44 µmol/L or the need for dialysis), prolonged ventilation (>24 h), days in intensive care unit (ICU), readmission in ICU, deep sternal wound infection (need for operative intervention and antibiotic therapy with positive culture), need for reoperation (major bleeding), total length of stay in hospital, and number transferred to another hospital or nursing home for further medication or rehabilitation.

Statistic methods

Continuous data were studied as mean ± standard deviations (SD) or median with range and compared using Student’s t-test or Kruskal Wallis test for non-parametric data. Categorical data were collected as numbers and percentages and compared using the chi-square test.

The validity to assess 30-day mortality by CAF was analyzed by receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves, and the area under the ROC curve (AUC) was calculated. Logistic regression was used to demonstrate the association between frailty and 30-day mortality and reported as odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI).To compare the three different risk scores models (EuroSCORE, STS score, and CAF score), Spearman’s rank correlation was used. To analyze the value of adding CAF score to the existing risk scores, multivariate logistic regression was used. Statistical significance was defined as p-values ≤ .05 and all p-values reported were two-sided. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 22 software (IBM Corp. Released 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

Sample size calculation for the overall study was based on the results of the Sündermann et al. study [Citation26]. These authors found that 50% of the patients were frail and observed a 1-year mortality of 7% in the non-frail group vs. 14% in the frail group. Based on a power of 80% and the risk of type I error of 5% inclusion of 600 would be sufficient.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board at the University of Copenhagen, reference number H-16020318. All patients provided verbal and written consent to the study.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The median age of the 604 patients was 73 years, the majority were male, about half of the cohort underwent isolated CABG and one third underwent combined procedure. The baseline demographics are shown in , stratified by non-frail and frail patients. For the risk scores evaluated, both EuroSCORE and STS scores were significant different in the two groups and overall the median risk scores were greateast with the EuroSCORE and in the frail patient group. All-cause mortality within 30-days was 2%. Cause of death was cardiac in seven patients, infection in one patient and intestinal ischemia in three patients. The median CAF Score for all patients was 7 (range, 1–30). Based on the CAF Score 454 (75%), patients were categorized as non-frail [median CAF score 6 (range, 1–10)] and 150 (25%) as frail [median CAF score 13 (range, 11–30)]. Frail patients were more likely to have a higher age, to be smokers, higher NYHA classification III and IV, higher median EuroSCORE and STS score, and a more complex surgery (). Furthermore, patients who were scored as frail had a higher prevalence of comorbidities, such as arrhytmia mainly atrial fibrillation and impaired renal function (). In the frailty group, 56% were admitted to cardiac surgery from their home compared to 70% in the non-frailty group (p = .001). Neither time on cardiopulmonary bypass or aortic cross-clamp time was significantly different between the frail group and the non-frail group (112.1 ± 50.3 vs. 104.4 ± 50.0 min, p = .14 and 75.2 ± 34.5 vs. 69.7 ± 38.3 min, p = .16).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients.

30-day outcomes

The 30-day mortality was four times higher in frail patients compared to in non-frail patients (). The patients who died within 30 days after surgery had a significantly higher CAF score (median CAF score 11 (5–22) vs. 8 (1–30), p = .039).

Table 2. Primary and secondary outcomes.

At least one MACCE was recorded for 23 patients (4%). Compared to non-frail patients, patients deemed frail had significantly four-fold higher risk of MACCE, three-times as many strokes, and twice as many acute myocardial infarctions ().

Postoperative complications

Frail patients had an increased risk of postoperative re-operations, atrial fibrillation, renal failure, prolonged ventilation, gastrointestinal complications, and delirium (). Furthermore, 50% of the patients in the frail-group had at least one blood transfusion compared to 30% in the non-frail group.

Table 3. Postoperative data.

The median length of stay in the ICU or readmission to the ICU in both groups were comparable, but frail patients had significantly longer ICU stay if readmitted [5 (2–25) vs. 2 (1–12), p < .001]. Frail patients had a longer total length of stay in hospital compared to non-frail patients and only 45% of the frail patients could be discharged directly to home from the Cardiac Surgery Department compared to 79% of the non-frail patients ().

Table 4. Hospitalization.

Comparison of risk scores

The CAF score was an independent risk factor of 30-day mortality (OR = 1.1, 95% CI 1.0–1.2, p = .044. Our univariate logistic regression analysis showed that gait speed was an independent predictor of mortality (OR = 5.0, 95% CI 1.6–16.0, p = .006) along with chair raise (OR = 1.6, 95% CI 1.1–2.4, p = .016). However, in multivariate logistic regression, each variable of the test had a p-value higher than .05. Using Spearman’s correlation analysis, we found a statistically significant correlation between CAF score and EuroSCORE (r = 0.351, p < .001) and between CAF score and STS score (r = 0.447, p < .001). In a multivariate logistic regression of CAF score and STS score and the CAF score and EursoSCORE, CAF score had a p-value higher than .05. The ROC curves are plotted in . The area under the ROC curve for EuroSCORE was 0.664 and 0.748 for STS. For CAF, an AUC of 0.700 was observed.

Discussion

We found that in a prospective cohort of patients above 65 years undergoing first-time cardiac surgery, 25% of the patients were frail according to the CAF score. Thirty-day mortality was four-fold higher in frail patients compared with non-frail patients. Also, we observed an increased risk of postoperative complications as well as a significant prolonged length of stay in hospital in frail patients. In comparison to EuroSCORE, and STS score the ROC curve analysis suggested similarity with the CAF score of predicting 30-day mortality.

In agreement with previous studies of frailty in patients undergoing cardiac surgery, we detected a strong correlation between frailty and early mortality and complications after cardiac surgery [Citation27]. Lee et al. were the first to evaluate frailty in patients in a retrospective study of 3826 undergoing cardiac surgery. These authors assessed frailty by daily activity using the Katz Index [Citation7]. The Katz Index consists of questions of independence in feeding, bathing, dressing, transferring, going to the restroom, and urinary continence, with the inclusion of a potential need of walking aid or assistance. Patients who had at least one of these, ambulation dependence, or diagnosed with dementia were defined as frail. Based on this definition, only 4.1% of the patients in the cohort were found frail, but the in-hospital mortality was 14.7% in frail patients compared to 4.5% in non-frail patients. Of note, this study included patients undergoing emergency surgeries and re-operations.

In the first study evaluating the CAF score, Sündermann et al. conducted a prospective observational study including 400 patients undergoing elective cardiac surgery, aged 74 years or older [Citation18]. These authors found that 50% of their cohort was deemed frail using the CAF score and the median CAF score was 11. The cohort included patients with higher mean age and more combined surgical procedures. Similar to our study, these authors found the CAF score to be a strong predictor for mortality after cardiac surgery and found a four times higher 30-day mortality in frail vs. non-frail patients.

In a study including 131 patients, frailty was simply measured by gait speed [Citation4]. The study included patients with a mean age of 76 years and undergoing elective first-time cardiac surgery. Forty-six percent of the patients were frail. Slow gait speed was a strong predictor for mortality and major morbidity after cardiac surgery. In this study, frailty (slow gait speed) was associated with ten-fold increased mortality and a two- to four-fold increased risk of morbidity postoperatively. Also, the validity of the STS scores improved after addition of gait speed to the algorithm.

Gait speed is an element in the CAF score. In our study, we evaluated gait speed and daily activity as single predictors and found that only gait speed was a predictor for mortality after cardiac surgery (p = .006).

Thus, previous studies have demonstrated the ability of different scores of frailty to predict mortality, as well as a significantly higher rate of postoperative complications and increased length of hospitalization in frail patients compared to non-frail patients. Our study has confirmed these findings.

The CAF score correlated well with the existing risk score models (STS score and Euroscore) and with the values partly overlaping it demonstrate potential to complement them. Still no statistical significance influence were found of adding the CAF score to the exisiting scores. However the ROC curve indicated similar prediction of 30-day mortality compared to EuroSCORE and STS score.

The importance of frailty has been addressed in the new versions of the EuroSCOREII and STS scores; the EuroSCORE II now includes poor mobility and the STS score (Version 2.73) now includes the 5-m gait speed. This has improved the prediction of 30-day mortality; however, still studies have shown the EuroSCORE has a tendency to overestimate and STS score a tendency to underestimate the mortality [Citation10,Citation11,Citation28]. To determine its clinical potential, the adding of a single frailty marker to the existing risk models needs to be tested in prospective cohorts.

To our knowledge, no validated scoring method is routinely used in the pre-surgical evaluation process before cardiac surgery. This is most likely due to the absence of an internationally accepted definition of frailty. The importance of a new and better predictor for outcomes after cardiac surgery, including frailty, are strongly requested in the rapidly growing population of aging and frail patients [Citation27]. The disadvantages of the CAF score model include the time consumption and equipment needed. It takes up to 20 min to complete the test, and some instruments are needed (e.g. a hand-held dynamometer and spirometry). Identifying a specific, strong predictor for frailty in the future might make these instruments superfluous and make testing easier, as we develop our understanding of the frailty concept.

A more accurate risk assessment would offer each patient a better risk-benefit evaluation and help in the design of tailored treatments for high-risk patients. Secondly, the high complication rates (transfusion, delirium, renal failure, and re-operations) seen in frail patients might be mitigated in many cases with the preoperative improvement of the baseline health status (physical, nutritional, renal parameters, hemoglobin, and mental status). This effort has been reported to improve postoperative outcomes and enhance recovery after cardiac surgery [Citation29]. Thirdly, using validated score systems can give guidance regarding resource distribution, such as ICU beds and rehabilitation facilities. This influences medical costs. Early identification of frail patients might reduce costs related to a length of hospital stay and resources used if preoperative health optimization and patient-tailored treatment can be offered using a validated assessment tool as the CAF score [Citation30].

Study limitations

There are some limitations to this study. It is a single-center study with an inherent risk of selection bias. Some of the patients tested were found to be very frail, and subsequently had their surgery canceled after a re-evaluation by the surgeon.

This study did not include patients in need of emergent surgery, which limits the applicability of the study findings to the patients requiring emergent surgery. The number of frail patients turned down for surgery at The Heart Team Conference is unknown.

In conclusion, the CAF score is a strong independent predictor of 30-day mortality in patients aged 65 years or older undergoing cardiac surgery. CAF score has a good correlation with EuroSCORE and STS score and, similar AUC for the prediction of 30 days mortatliy. Still no influence were found when adding CAF score to the existing scores. Our findings highlight the importance of and need for a better predictive scoring model for patients undergoing cardiac surgery. A frailty score taking 10 to 20 min preoperative must be practically reasonable given that it has been proven to be such a strong predictor.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alexander KP, Newby LK, Cannon CP, et al. Acute coronary care in the elderly, part I: non-ST-segment-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology: in collaboration with the Society of Geriatric Cardiology. Circulation. 2007;115:2549–2569.

- Goldberg RJ, Yarzebski J, Lessard D, et al. A two-decades (1975 to 1995) long experience in the incidence, in-hospital and long-term case-fatality rates of acute myocardial infarction: a community-wide perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1533–1539.

- Alexander KP, Anstrom KJ, Muhlbaier LH, et al. Outcomes of cardiac surgery in patients > or = 80 years: results from the National Cardiovascular Network. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:731–738.

- Afilalo J, Eisenberg MJ, Morin J-F, et al. Gait speed as an incremental predictor of mortality and major morbidity in elderly patients undergoing cardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1668–1676.

- Green P, Woglom AE, Genereux P, et al. The impact of frailty status on survival after transcatheter aortic valve replacement in older adults with severe aortic stenosis: a single-center experience. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:974–981.

- Schoenenberger AW, Stortecky S, Neumann S, et al. Predictors of functional decline in elderly patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI). Eur Heart J. 2013;34:684–692.

- Lee DH, Buth KJ, Martin B-J, et al. Frail patients are at increased risk for mortality and prolonged institutional care after cardiac surgery. Circulation 2010;121:973–978.

- Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173:489–495.

- Stortecky S, Schoenenberger AW, Moser A, et al. Evaluation of multidimensional geriatric assessment as a predictor of mortality and cardiovascular events after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:489–496.

- Noyez L, Kievit PC, van Swieten HA, et al. Cardiac operative risk evaluation: the EuroSCORE II, does it make a real difference? Neth Heart J. 2012;20:494–498.

- Shih T, Paone G, Theurer PF, et al. The society of thoracic surgeons adult cardiac surgery database version 2.73: more is better. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100:516–521.

- Di Dedda U, Pelissero G, Agnelli B, et al. Accuracy, calibration and clinical performance of the new EuroSCORE II risk stratification system. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;43:27–32.

- Koene B, Van Straten AHM, Soliman Hamad MA, et al. Predictive value of the additive and logistic EuroSCOREs in patients undergoing aortic valve replacement. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2011;25:1071–1075.

- Qadir I, Salick MM, Perveen S, et al. Mortality from isolated coronary bypass surgery: a comparison of the society of thoracic surgeons and the EuroSCORE risk prediction algorithms. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2012;14:258–262.

- de Arenaza DP, Pepper J, Lees B, et al. Preoperative 6-minute walk test adds prognostic information to Euroscore in patients undergoing aortic valve replacement. Heart 2010;96:113–117.

- Afilalo J, Mottillo S, Eisenberg MJ, et al. Addition of frailty and disability to cardiac surgery risk scores identifies elderly patients at high risk of mortality or major morbidity. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:222–228.

- Sündermann SH, Dademasch A, Seifert B, et al. Frailty is a predictor of short- and mid-term mortality after elective cardiac surgery independently of age. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2014;18:580–585.

- Sündermann S, Dademasch A, Praetorius J, et al. Comprehensive assessment of frailty for elderly high-risk patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac. Surg. 2011;39:33–37.

- Afilalo J, Alexander KP, Mack MJ, et al. Frailty assessment in the cardiovascular care of older adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:747–762.

- Lytwyn J, Stammers AN, Kehler DS, et al. The impact of frailty on functional survival in patients 1 year after cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;154:1990–1999.

- Rodríguez-Pascual C, Paredes-Galán E, Ferrero-Martínez AI, et al. The frailty syndrome and mortality among very old patients with symptomatic severe aortic stenosis under different treatments. Int J Cardiol. 2016;224:125–131.

- Chung CJ, Wu C, Jones M, et al. Reduced handgrip strength as a marker of frailty predicts clinical outcomes in patients with heart failure undergoing ventricular assist device placement. J Card Fail. 2014;20:310–315.

- Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol Med Sci 2001;56:146–157.

- Vilagut G, Forero CG, Barbaglia G, et al. Screening for depression in the general population with the center for epidemiologic studies depression (CES-D): a systematic review with meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0155431.

- Kojima G. Quick and simple frail scale predicts incident activities of daily Living (ADL) and Instrumental ADL (IADL) disabilities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMDA 2018;19:1063–1068.

- Sündermann S, Dademasch A, Rastan A, et al. One-year follow-up of patients undergoing elective cardiac surgery assessed with the comprehensive assessment of frailty test and its simplified form. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2011;13:119–123.

- Abdullahi YS, Athanasopoulos LV, Casula RP, et al. Systematic review on the predictive ability of frailty assessment measures in cardiac surgery. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2017;24:619–624.

- Nashef SAM, Roques F, Sharples LD, et al. EuroSCORE II. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;41:734–745.

- Arora RC, Brown CH, Sanjanwala RM, et al. New prehabilitation: a 3-way approach to improve postoperative survival and health-related quality of life in cardiac surgery patients. Can J Cardiol. 2018;34:839–849.

- Pattakos G, Johnston DR, Houghtaling PL, et al. Preoperative prediction of non-home discharge: a strategy to reduce resource use after cardiac surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214:140–147.