Abstract

Objectives. We hypothesized, that patients with peripheral arterial disease (PAD) are less aware of risk factors and possible outcomes of the disease compared to patients with coronary artery disease (CAD), which are similar. Hence, the aim of this study was to evaluate awareness of and attitudes towards PAD and CAD among patients, who are already diagnosed with either disease. Design. A cross-sectional descriptive study was performed. Basic demographics, the presence and awareness of risk factors for PAD and CAD; perceived systemic and limb consequences, severity of PAD and CAD, self-reported knowledge about other non-vascular illnesses were assessed using an anonymous questionnaire. Results. 203 were invited and 157 (77%), 63 with PAD and 94 with CAD, patients agreed to take part in and completed the survey. Basic demographic characteristics were similar in both groups, except for the level of education: PAD patients were less educated compared to CAD patients (p = .002). Only 35% of PAD patients were familiar with the definition of PAD (key words were registered) in contrast to 52% CAD definition awareness among CAD patients (p = .034). PAD patients were significantly less familiar with other common diseases (p = .002) and risk factors for both PAD (p < .001) and CAD (p = .003) in comparison to equivalent CAD group parameters. Conclusions. PAD patients are less aware of risk factors for PAD and atherosclerosis in general, other illnesses and have lower level of education, which may negatively affect overall management of this complex disease.

Introduction

During the last decade, public health issues changed significantly. Nowadays, noncommunicable diseases are a major public health issue both in high-income and low-income countries [Citation1,Citation2]. Non-communicable diseases are the leading cause of morbidity, mortality and reduced quality of life. This is to be expected as the world population is aging and people in low-income countries are becoming more exposed to risk factors for chronic diseases, especially for cardiovascular diseases [Citation3–6].

Three diseases: coronary artery disease (CAD), cerebrovascular disease (CVD) and peripheral artery disease (PAD), reflect three main atherosclerotic syndromes. PAD patients have a worse prognosis for a major cardiovascular event within 1 year compared with patients suffering from CAD or CVD [Citation7–10]. In 2010 there were 202 million people worldwide affected by PAD. Current data suggests it is a rise by 28.7% in low-income countries and 13.1% in high-income countries compared with the previous decade [Citation11]. Up to 75% of those with PAD have atypical symptoms and only 10-20% have typical intermittent claudication [Citation12,Citation13]. The overall mortality in PAD population is 30% within 5 years and 50% at 10 years mostly from the major cardiovascular event (stroke or heart attack) [Citation14,Citation15].

Despite the growing prevalence and poor prognosis, PAD is still under-recognized and undertreated [Citation16–19]. Risk factor modification, adherence to treatment and recognition of possible outcomes of the disease are essential for successful treatment. These aspects are highly dependent on the patient perception of this illness. We hypothesized, that patients with PAD are less aware of the aforementioned factors compared to CAD patients, who share common risk factors and outcomes of their disease. Hence, the aim of this study was to evaluate awareness of and attitudes to PAD and CAD among patients, who are already diagnosed with one of the diseases. It included related terminology, major risk factors, and possible outcomes of the diseases.

Materials and methods

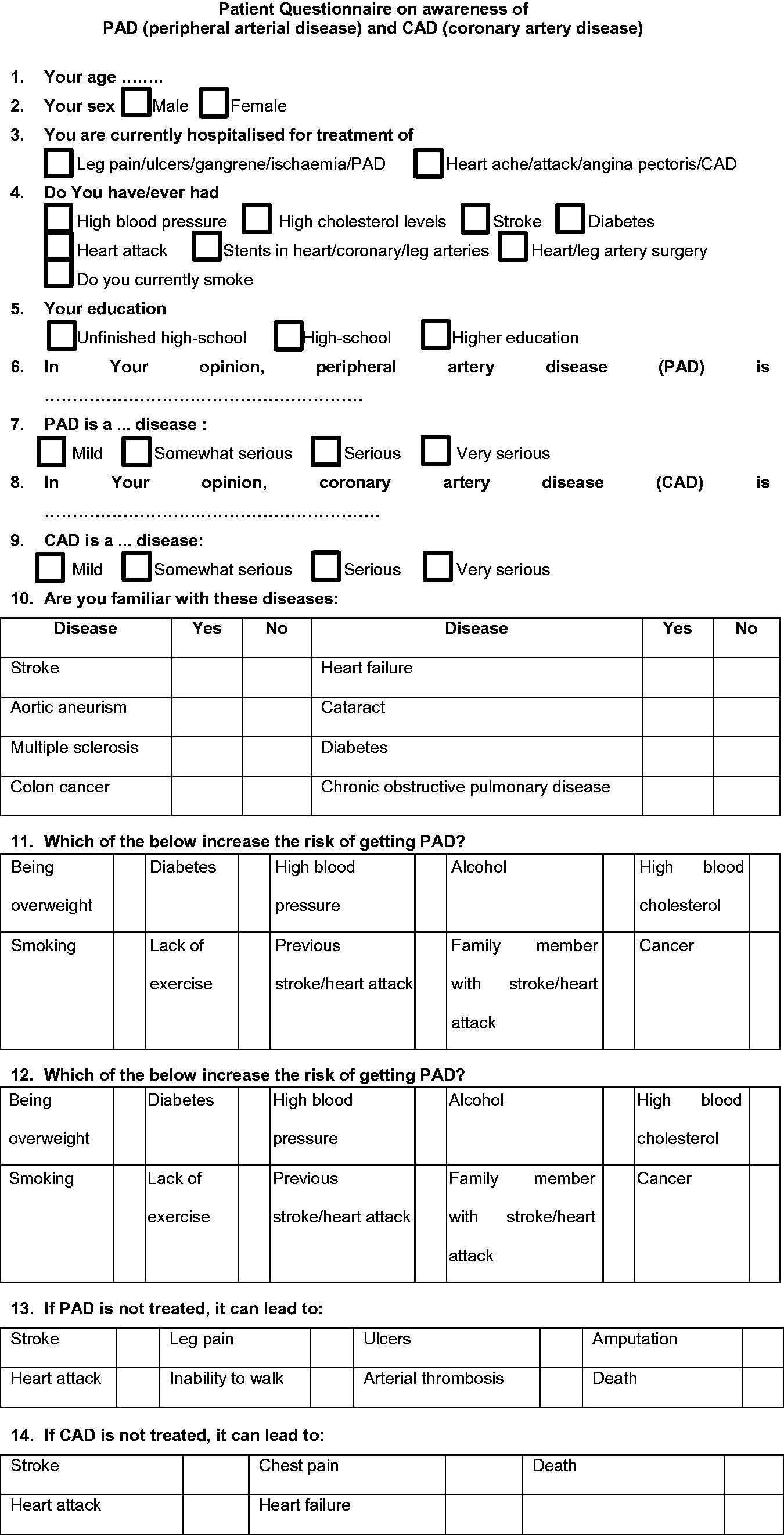

A cross-sectional descriptive study in a tertiary university teaching hospital from December 1st, 2015 through April 1st, 2016 was performed. In-patients already diagnosed with either CAD or PAD and hospitalised for further interventions after ambulatory treatment due to disease progression were interviewed face-to-face by either one of two investigators (I.U.B., E.B.). Two groups were formed according to which disease – PAD or CAD – was predominantly treated at the time irrespective of other comorbidities. Basic demographics, the presence and awareness of risk factors for PAD and CAD; possible consequences, severity of PAD and CAD, self-reported knowledge about other non-vascular illnesses in Lithuania were assessed using an anonymous questionnaire (Appendix 1), based on the study by Cronin et al [Citation19]. A pilot trial of the questionnaire before the study was tested on 16 individuals, which resulted in minor edits of the original version.

Ethical approval to conduct the study was granted by the institutional review board. The study was performed according to Declaration of Helsinki.

A total of 203 patients hospitalized for further interventions despite conservative treatment on either cardiology or vascular surgery wards were invited to participate. The purpose of the study was verbally explained and written informed consent was obtained from all those who agreed to participate. All questionnaires were completely anonymous. Participants, who had medical/nursing degree and those who could not answer the questions physically or mentally were excluded from the study.

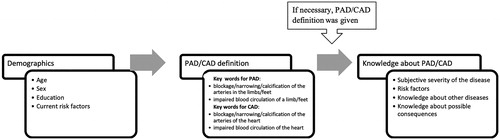

If the participant was not aware of the term “peripheral arterial disease” or “coronary artery disease”, an explanation of the condition was given (). Awareness of PAD was approved if the person mentioned keywords such as “blockage/narrowing/calcification of the arteries in the limbs/feet” or/and “impaired blood circulation of a limb/feet”. Keywords for CAD awareness included “blockage/narrowing/calcification of the arteries of the heart” or/and “impaired blood circulation of the heart”.

Figure 1. Principal scheme of the interview. CAD: coronary artery disease; PAD: peripheral artery disease

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Version 23 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD or otherwise stated. Continuous variables were checked for normal distribution by Shapiro-Wilk test and compared by Student’s t-test when normally distributed or by the Mann-Whitney test for abnormally distributed variables. Categorical variables were compared by Chi-Square test or Fisher's exact test as appropriate. A p value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

157 (77%) out of 203 invited patients agreed to take part and completed the survey. There were 63 patients with PAD and 94 patients with CAD.

Demographic characteristics

Demographic characteristics are presented in . Basic demographic characteristics were similar in both groups, except for the level of education.

Table 1. Basic demographics.

The mean age of patients in PAD and CAD group was 68.29 (± 11.8) years and 66.36 (± 10.1) years respectively. There were more men in PAD + group. A number of reported cardiovascular risk factors and smoking prevalence was similar between the groups.

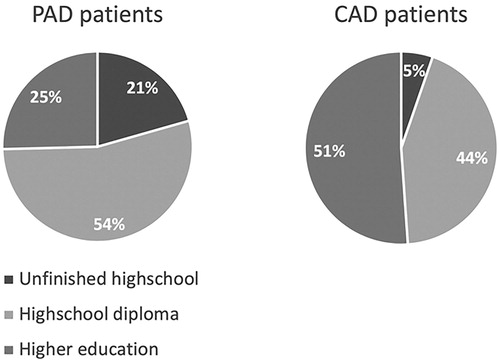

PAD patients had lower educational level compared to CAD patients (p = .002) (). Twice as many CAD patients had higher or university education in contrast to PAD + patients.

Figure 2. Level of education. PAD + patients: patients with peripheral artery disease; CAD + patients: patients with coronary artery disease.

PAD patients were trending to take less medications in comparison with CAD patients. Diference between goups was observed only for statins (p = .003).

Knowledge of cardiovascular risk factors and other illnesses

Patients in both groups demonstrated a high awareness of other common diseases, though PAD group was less informed (p = .002) ().

Table 2. Knowledge of cardiovascular risk factors, common illnesses, PAD, CAD and their perceived consequences.

PAD patients were less familiar with risk factors for both PAD (p < .001) and CAD (p = .003) in comparison to equivalent CAD parameters.

Knowledge about PAD and perceived consequences

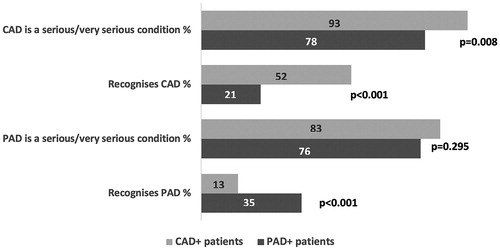

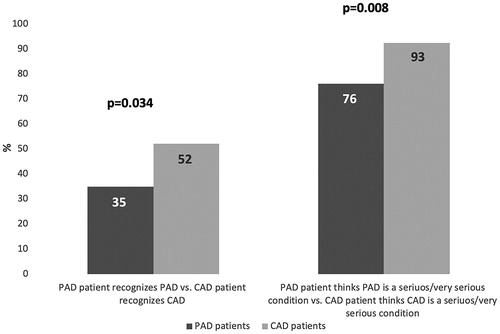

Only about a third of PAD patients were familiar with the definition of PAD in contrast to 52% CAD definition awareness among CAD patients (p = .034) (, ). The awareness of PAD was very low in CAD group – only around tenth of interviewees could describe it. Noteworthy to mention is that subjective perception about the seriousness of both conditions also differed - roughly twenty percent less patients in PAD group compared to CAD group thought that their disease is serious/very serious (p = .0078).

Figure 3. Perception of disease severity. CAD: coronary artery disease; PAD: peripheral artery disease

Figure 4. Perception differences between PAD patients and CAD patients. CAD – coronary artery disease, PAD – peripheral artery disease

Knowledge about potential consequences of PAD among patients with the disease was limited (). Though insignificantly, CAD patients performed better in this section. These differences were even greater when asked about possible consequences of CAD.

Discussion

The major findings of our study are:

just around every third patient diagnosed with PAD adequately understands her disease;

less PAD patients compared to patients with CAD perceive their diseases as serious one;

PAD patients are less aware of other illnesses and risk factors for PAD and atherosclerosis in general;

PAD patients are less educated all of which may negatively affect overall management of this complex disease.

Public awareness of PAD despite growing prevalence and disabling outcomes is still low [Citation16–19]. Our results show that not only the general public but even patients themselves are quite ignorant to their disease. We found just two other studies, which investigated the perception of PAD by affected patients [Citation18,Citation20]. More than a decade after the last study, results are quite similar – PAD patients underestimate their high personal risk of major cardiovascular event and death as compared to those with CAD. This may indicate that in spite of rapidly developing new treatment methods, patient education strategies do not evolve equally fast.

Patient attitude towards her disease and its management plays a crucial role in successful treatment. This is backed up by Naderi et al., who found out that patient adherence to cardiovascular risk lowering medication is between 50–66% and neither their side-effects nor price are the major factors accounting for poor compliance [Citation21]. This finding is important as cardiovascular risk factors are common to PAD. According to our findings, PAD patients are poorly aware of the risk factors, which is in line with conclusions by group of scientists in a qualitative study concluded, that PAD + patients in UK experience lack of information about the disease, its risk factors, lifestyle change (including supervised exercise therapy) effects on disease progress as well as lack of support and empathy [Citation22]. Considering all of the above we may assume that PAD patient’s compliance to first line conservative treatment options [Citation23–26] is suboptimal which may compromise good outcomes.

An important finding of our study is that patients with PAD were significantly less educated. Level of education is the socioeconomic status indicator. Some researchers suggest that poor socioeconomic status is one of the reasons of late diagnosis, faster functional decline and poor treatment outcomes of PAD even when accounted for healthcare disparities, race, sex and etc. [Citation27–32]. Up to date, several studies have already concluded, that antiplatelet therapy, statins and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors are underused in PAD + cohort compared to CAD + cohort [Citation33–36]. Furthermore, the risk of limb complications and death are overestimated in comparison to underestimation of systematic complications among general physicians [Citation37]. Considering all of the above, it may be argued that patients who know more about PAD just get admitted as in-patients less often due to better conservative treatment. More research is necessary to test these assumptions. But it is clear, that patients already suffering from chronic lower limb ischemia should be educated more about their disease, risk factors and consequences both by general practitioners and vascular surgeons.

Our study has some limitations. Firstly, atherosclerotic risk factors were reported by patients, that is, they were not linked with objective clinical data (cholesterol levels and etc.). Secondly, patients, who had more than one atherosclerotic syndrome (CAD, CVD, etc) were not excluded or separated into a separate group. This could have led to an overestimation of CAD awareness among PAD patients and vice versa.

Disclosure statement

None.

References

- GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet Lond Engl. 2015;385:117–171.

- Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet Lond Engl. 2015;386:743–800.

- Ding D, Lawson KD, Kolbe-Alexander TL, et al. The economic burden of physical inactivity: a global analysis of major non-communicable diseases. Lancet Lond Engl. 2016;388:1311–1324.

- Farzadfar F, Finucane MM, Danaei G, et al. National, regional, and global trends in serum total cholesterol since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 321 country-years and 3·0 million participants. Lancet. 2011;377:578–586.

- Danaei G, Finucane MM, Lin JK, et al. National, regional, and global trends in systolic blood pressure since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 786 country-years and 5·4 million participants. Lancet. 2011;377:568–577.

- Finucane MM, Stevens GA, Cowan MJ, et al. National, regional, and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9·1 million participants. Lancet. 2011;377:557–567.

- Sabouret P, Cacoub P, Dallongeville J, et al. REACH: international prospective observational registry in patients at risk of atherothrombotic events. Results for the French arm at baseline and one year. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2008;101:81–88.

- Reid CM, Ademi Z, Nelson MR, et al. Outcomes from the REACH Registry for Australian general practice patients with or at high risk of atherothrombosis. Med J Aust. 2012;196:193–197.

- Valentijn TM, Stolker RJ. Lessons from the REACH Registry in Europe. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2012;10:725–727.

- Steg PG, Bhatt DL, Wilson PWF, et al. One-year cardiovascular event rates in outpatients with atherothrombosis. JAMA. 2007;297:1197–1206.

- Fowkes FGR, Rudan D, Rudan I, et al. Comparison of global estimates of prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2000 and 2010: a systematic review and analysis. Lancet Lond Engl. 2013;382:1329–1340.

- Stoffers HE, Rinkens PE, Kester AD, et al. The prevalence of asymptomatic and unrecognized peripheral arterial occlusive disease. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25:282–290.

- Beckman JA, Jaff MR, Creager MA. The United States preventive services task force recommendation statement on screening for peripheral arterial disease. Circulation. 2006;114:861–866.

- Hajibandeh S, Hajibandeh S, Shah S, et al. Prognostic significance of ankle brachial pressure index: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vascular. 2016;52:208–224

- Ankle Brachial Index Collaboration, Fowkes FGR, Murray GD, et al. Ankle brachial index combined with Framingham Risk Score to predict cardiovascular events and mortality: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:197–208.

- Hirsch AT, Murphy TP, Lovell MB, et al. Gaps in public knowledge of peripheral arterial disease: the first national PAD public awareness survey. Circulation. 2007;116:2086–2094.

- Lovell M, Harris K, Forbes T, et al. Peripheral arterial disease: lack of awareness in Canada. Can J Cardiol. 2009;25:39–45.

- Willigendael EM, Teijink J. a W, Bartelink M-L, et al. Peripheral arterial disease: public and patient awareness in The Netherlands. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2004;27:622–628.

- Cronin CT, McCartan DP, McMonagle M, et al. Peripheral artery disease: a marked lack of awareness in Ireland. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015;49:556–562.

- McDermott MM, Mandapat AL, Moates A, et al. Knowledge and attitudes regarding cardiovascular disease risk and prevention in patients with coronary or peripheral arterial disease. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2157–2162.

- Naderi SH, Bestwick JP, Wald DS. Adherence to drugs that prevent cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis on 376,162 patients. Am J Med. 2012;125:882.e1–887.e1.

- Gorely T, Crank H, Humphreys L, et al. “Standing still in the street”: experiences, knowledge and beliefs of patients with intermittent claudication–a qualitative study. J Vasc Nurs. 2015;33:4–9.

- Peripheral arterial disease: diagnosis and management. Guidance and guidelines. NICE [Internet]. [cited 2017 Aug 15]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG147/chapter/1-Guidance#management-of-intermittent-claudication.

- Gerhard-Herman MD, Gornik HL, Barrett C, et al. 2016 AHA/ACC guideline on the management of patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2017;135:e686–e725.

- Norgren L, Hiatt WR, Dormandy JA, et al. Inter-society consensus for the management of peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg. 2007;26:81–157.

- Ultee KHJ, Bastos Gonçalves F, Hoeks SE, et al. Low socioeconomic status is an independent risk factor for survival after abdominal aortic aneurysm repair and open surgery for peripheral artery disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015;50:615–622.

- Giacovelli JK, Egorova N, Nowygrod R, et al. Insurance status predicts access to care and outcomes of vascular disease. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:905–911.

- Loehrer AP, Hawkins AT, Auchincloss HG, et al. Impact of expanded insurance coverage on racial disparities in vascular disease: insights from Massachusetts. Ann Surg. 2016;263:705–711.

- Ultee KHJ, Hoeks SE, Gonçalves FB, et al. Peripheral artery disease patients may benefit more from aggressive secondary prevention than aneurysm patients to improve survival. Atherosclerosis. 2016;252:147–152.

- Henry AJ, Hevelone ND, Belkin M, et al. Socioeconomic and hospital-related predictors of amputation for critical limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53:330–339.e1.

- Durham CA, Mohr MC, Parker FM, et al. The impact of socioeconomic factors on outcome and hospital costs associated with femoropopliteal revascularization. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:600–606. discussion 606–607.

- McDermott MM, Polonsky TS, Kibbe MR, et al. Racial differences in functional decline in peripheral artery disease and associations with socioeconomic status and education. J Vasc Surg. 2017;66:826–834

- Hirsch AT, Criqui MH, Treat-Jacobson D, et al. Peripheral arterial disease detection, awareness, and treatment in primary care. JAMA. 2001;286:1317–1324.

- Ardati AK, Kaufman SR, Aronow HD, et al. The quality and impact of risk factor control in patients with stable claudication presenting for peripheral vascular interventions. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:850–855.

- Subherwal S, Patel MR, Kober L, et al. Missed opportunities: despite improvement in use of cardioprotective medications among patients with lower-extremity peripheral artery disease, underuse remains. Circulation. 2012;126:1345–1354.

- Lindahl AK. Comments regarding “a systematic review of implementation of established recommended secondary prevention measures in PAOD.”. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;39:87–88.

- Haigh KJ, Bingley J, Golledge J, et al. Barriers to screening and diagnosis of peripheral artery disease by general practitioners. Vasc Med. 2013;18:325–330.

Appendix 1