Abstract

Objectives. Assess the short- and long-term survival for patients who underwent isolated coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and evaluate the impact of gender and age. Furthermore to assess the long-term survival in the CABG group compared to the general population. Design. This study included 4044 consecutive patients who underwent isolated CABG at Oslo University Hospital, Ullevål, in Oslo, Norway in the time period from 01 January 2003 to 31 December 2015. Patient data was collected retrospectively from the quality register at the department. Information on survival status was obtained from the Norwegian National Registry. Life expectancy data for the general population was gained from Statistics Norway. Results. Female patients were significantly older than male patients at the time of surgery (mean age 67.0 and 63.9 years, respectively, p < .001), and had significantly lower 30-day survival (mortality was 1.4% and 0.6%, respectively, p = .017). Male gender was independently associated with lower long-term survival (p = .0037) in a multivariate analysis. Male patients aged less than 60 years also showed significantly lower long-term survival (SMR = 1.84, 95% CI = 1.49–2.25) compared to the age-matched general population. Among patients older than 60 years, survival was similar to survival in the age-matched general population. Conclusions. Survival was excellent for patients undergoing surgery. Despite increased age and operative mortality, female patients had better adjusted long-time survival than male patients. There was lower long-term survival among male patients aged less than 60 compared to the general population. Our findings may help clinicians in selecting appropriate patients for surgery.

Introduction

Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) was established as a surgical procedure in the late 1960s. The first CABG operation in Norway was performed in 1969 [Citation1]. The annual number of CABG operations in Norway has been decreasing since the mid-2000s. Contributing heavily to this is the rise of less invasive methods, such as percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) [Citation2]. However, CABG is still one of the most common cardiac surgeries performed in Norway. In 2016, 286 patients underwent a CABG operation at Oslo University Hospital [Citation2].

Although PCI is chosen over CABG in most patients with coronary disease, still a substantial number of patients undergo CABG. Therefore, it is important to continuously assess outcome, survival and associated risk factors in this patient group. This is important to be able to select suitable patients for surgery. The impact of gender on survival after CABG has been previously reported, although with differing results [Citation3–5]. Most relevant studies conclude with a gender difference in short-term survival, disfavoring female gender [Citation3–8]. Gender is included as a variable when calculating EuroSCORE.

Since the results of cardiac surgery have improved over time, we wanted to assess the outcome using a recent patient population. In the present study, we tried to expand the knowledge about gender differences in survival after CABG. The aim was to assess the short- and long-term survival for patients who underwent CABG and evaluate the impact of gender and age at the time of surgery. Furthermore, we aimed to evaluate the long-term survival in the CABG group compared to the general population. On these topics, the present study is one of the few large, recent cohorts with long follow-up time.

Material and methods

This is a retrospective study that includes four thousand and forty-four consecutive patients who underwent an isolated CABG operation at Oslo University Hospital, Ullevål, in the time period from 01 January 2003 to 31 December 2015. All elective, emergency and redo CABG surgeries are included. Almost all the patients were operated using extracorporeal circulation. All the surgeries were performed through a median sternotomy. The internal mammary artery (IMA) was routinely used in revascularization of the left anterior descending artery (LAD). The great saphenous vein was routinely used for other grafted coronary arteries.

The patient data was collected from the quality register at the Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery. All cases of isolated CABG were identified and controlled for duplicates and the extracted data were anonymized according to the Norwegian rules for quality studies on data from patient registers. The endpoint was death of all causes.

Date of death is registered in the department’s quality register by use of the Norwegian National Registry. The department’s quality register is regularly updated. The National Registry contains information of everyone that resides or has resided in Norway. The latest update of the department’s quality register prior to the extraction of data for this study was in January 2017. In order to improve statistical power, the follow-up period was set to a maximum of ten years. This is because relatively few patients were followed up for longer than 10 years. Data on the general population was gathered from Statistics Norway [Citation9].

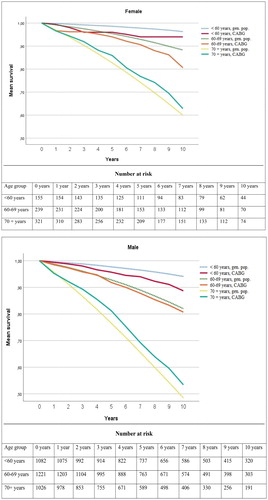

For the Kaplan–Meier analysis, the patient group was divided by gender. Moreover, each gender group was divided into three different age groups: Less than 60 years, 60–69 years and 70+ years. This division was based on the patients’ age at the time of surgery. Thus, the patients were divided in a total of six different groups. The general population during the observational period was divided in the same way, to make a valid comparison to the CABG patient group. The youngest patient in our cohort was 29 years at the time of surgery.

Multivariate analysis was calculated for diabetes Mellitus (DM), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), peripheral vascular disease, renal failure and body mass index (BMI). DM is defined as treated DM. COPD is defined as treated with broncholytics and/or steroids. Peripheral vascular disease is defined as claudicatio, carotic stenosis, or planned or completed vascular surgery or x-ray intervention. Renal failure is defined as creatinine >200 µmol/l or anuria.

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. To protect the privacy of the subjects, the data that was provided from the department’s registry was anonymized. Thus, it was not possible for the authors to obtain informed consent. As a quality study with anonymized data, the study was exempt from approval by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics according to Norwegian regulations. The study was approved by the head of the Department and recommendation in processing personal data or health information was given by the hospital's data protection officer according to institution protocol.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was computed by use of IBM SPSS version 23-25. Descriptive data was calculated for the entire patient group and for each gender separately. A chi-square test was used to examine the effect of gender on 30-day mortality. The gender differences in categorical variables were assessed by using chi-square test. The gender differences in age at the time of surgery, BMI and number of grafts were assessed with t tests, while difference in EuroSCORE I was assessed with Mann–Whitney U test.

The long-term survival was adjusted for age and other variables and compared between the genders by using Cox regression analysis. Kaplan–Meier curves were used to estimate the mortality during 10 years. Data from Statistics Norway was used to estimate age and time period-matched mortality during 10 years in the general Norwegian population. To evaluate whether a mortality curve from the CABG study differed significantly from a corresponding mortality curve from the general population, a standardized mortality rate (SMR) with 95% confidence interval was calculated. The assumptions of the proportional-hazards model were checked for each Cox regression model and found to be adequately met.

Results

Patient characteristics

Of the 4044 patients, 715 patients (17.7%) were female. The mean age of the patients at the time of surgery was 64.5 years. The mean age of the female patients was 67.0 (SD 9.9) years, while the mean age of the male patients was 63.9 (SD 9.7) years (p < .001). The maximum follow-up time was 10 years, and the median follow-up time was 6.7 years.

The prevalence of peripheral vascular disease was significantly higher among the female compared to the male patients (p = .020). There was no statistically significant difference between the genders in prevalence of COPD, left main stem stenosis, diabetes mellitus or renal failure. Female patients had a significantly higher median preoperative EuroSCORE I (5 vs. 3, p < .001). A significantly larger proportion of the operations on female patients were emergency operations compared to male patients and more women were operated without cardiopulmonary bypass. Male patients received slightly more grafts. displays patient and operation characteristics.

Table 1. Patient and operation characteristics.

Survival

During the observational period, 669 (16.5%) of the patients died. 29 (0.7%) died within 30 days of surgery. 119 (16.6%) of the female patients died, while 550 (16.5%) of the male patients died. Females had significantly higher 30-day mortality than males (p = .017). Kaplan–Meier estimates for survival 1 year, 5 years and 10 years after surgery are presented in .

Table 2. The estimated survival for male and female patients 1 year, 5 years and 10 years after the surgery.

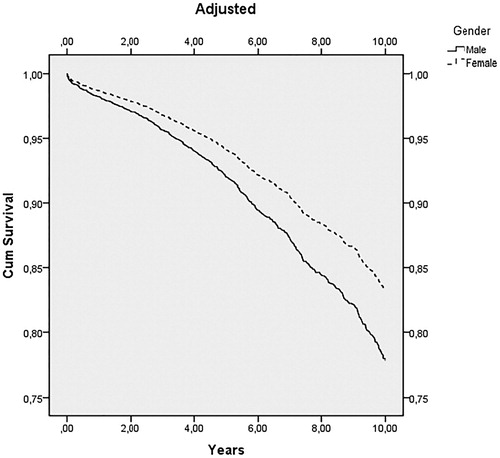

Before any variable adjustment, there was no difference in the long-term survival between the genders (p = .74). However, there was a significant gender difference (p = .0037) when adjusting for age and other pre-operative variables, which are listed in . Females showed better survival. This is illustrated in .

Table 3. Multivariate analysis of pre-operative variables with corresponding p-value.

The prevalence of peripheral vascular disease was significantly higher among the female compared to the male patients (p = .020). There were no statistically significant differences between the genders in mean BMI or prevalence of COPD, diabetes mellitus or renal failure. Female patients had a significantly higher median pre-operative EuroSCORE I (5 vs. 3, p < .001).

The survival of operated patients was compared to age-matched survival in the general population during the observational period. In , two graphs, one for each gender, illustrate the estimated survival of the patient group compared to the general population.

Figure 2. Kaplan–Meier curves and number at risk for both genders categorized in different age groups.

The standardized mortality rate (SMR) was calculated for each group. The results are presented in . Males aged less than 60 years were found to have a statistically significant higher mortality than the matched background population. Among patients older than 60 years, survival was similar to age-adjusted survival in the general population.

Table 4. Standardized mortality rate for male and female patients in various age groups, with 95 % confidence intervals.

Discussion

In the present study, we found that female patients had lower 30-day survival after isolated CABG compared to male patients, although the overall survival was high. Female patients were significantly older at the time of surgery than male patients. When adjusting for selected pre-operatively registered risk factors, female patients had better long-term survival than male patients. When compared to the age-matched general population, male patients under the age of 60 had inferior long-term survival. Patients older than 60 years had similar long-term survival as the age-matched general population.

The lower short-term survival in female patients is consistent with findings in previous studies, and female gender is included as a risk factor in the EuroSCORE. Other studies have discussed whether female gender is an independent risk factor for lower short-term survival. Some studies report that female gender, when adjusted for confounding variables, does not predict short-term survival [Citation10–12]. On the contrary, a large meta-analysis by Alam et al from 2013 reported that female gender was independently associated with decreased survival [Citation5], and other studies have showed decreased short-term survival in females when adjusting for age and other pre-operative risk factors [Citation8,Citation13–15]. We found that female patients had a significantly higher median EuroSCORE I. It is important to take into account that female gender is a risk factor in EuroSCORE I, and that female patients were older.

The female patient group in our study was significantly older than the male patient group, and this might have affected both short- and long-term survival. The majority of other studies have shown that female CABG patients have a higher degree of comorbidity [Citation5]. This leads to speculation as to whether this might be a reason for the survival difference. However, of the pre-operative risk factors examined in our analysis, only peripheral vascular disease was found to be significantly more common in female patients. Compared to operations on male patients, a larger proportion of operations on female patients were emergency operations. This might have influenced the short-term survival. Although females have lower 30-day survival, this survival was still very high in our study.

Furthermore, in our study there was a significant difference in longterm survival between the genders when adjusting for age, BMI and pre-operatively diagnosed COPD, peripheral vascular disease, kidney failure and diabetes mellitus. Female patients showed a better survival than male patients over the 10 years of follow-up. This finding is consistent with some other studies [Citation16,Citation17]. Guru et al. reported that the female patients have equal or better long-term survival than male patients [Citation13]. Other studies have shown conflicting findings regarding differences in long-term survival between the genders [Citation11–13,Citation18]. The finding in our study could partly be explained by the higher life expectancy of women compared to men in the general population.

When compared to the age-matched general population, male patients aged less than 60 years showed poorer long-term survival in our study. This can be at least partly explained by more pronounced cardiovascular disease, which has required CABG surgery at an early age. In addition, the prevalence and severity of cardiovascular disease increases with age. This implies that the difference between the patients and the age-matched general population is more marked in the younger age groups.

Patients who undergo CABG surgery have serious cardiovascular disease, with potentially fatal outcome. However, patients older than 60 years did not show worse long-term survival than the age-matched general population. A possible explanation is that the patients undergo a treatment that has a well-established effect on survival [Citation19]. Furthermore, patients who are considered suitable for CABG surgery represent a selected group with a limited extent of comorbidity. Another contributing factor could be that patients who undergo a CABG operation get closer medical follow-up than the general population.

A study from Trondheim, Norway from 2016 followed patients that had undergone CABG, aortic valve replacement (AVR) or both. This study reported that female patients and patients in the age groups under 60 years and 60–69 years had reduced long-term survival compared to the general population, while male patients older than 70 years had improved survival [Citation20]. The findings regarding female patients, male patients older than 70 years and patients in the age group 60–69 years differ from the findings in our study. A possible reason is the inclusion of AVR-operated patients in that study, in contrast to ours.

A study published in 1997 from Rikshospitalet in Oslo also compared the long-term survival of CABG patients to a matched part of the general population [Citation21]. In this study the survival in the patient population was reduced when compared to the general population. Thus, the findings in that study differ from ours. There are several possible reasons for this. Improvement of treatment and differences in selection criteria are plausible explanations.

When evaluating whether a patient should undergo CABG surgery, both the short- and long-term survival of surgery must be considered. Therefore, the findings of the present study might be relevant to clinicians selecting patients for CABG surgery. The results of the study may also be relevant for patients when they make informed decisions regarding whether to undergo surgery or not. Our study might contribute to the general knowledge about survival after CABG surgery.

The strength of this study is that the sample size is large, and that the patients have been followed up for a long time. A limitation of the study is that the female patient population was much smaller than the male. However, it should be noted that this is the case for most similar studies. Another limitation is that the number of variables included in the multivariate analysis could have been larger.

Conclusion

In this study, we have shown excellent survival for patients undergoing CABG surgery. Moreover, we found that female patients who underwent isolated CABG showed lower 30-day survival when compared to male patients. Female patients were significantly older at the time of surgery. On the other hand, female patients showed better long-term survival compared to male patients when adjusting for age and selected pre-operative variables. Only male patients aged less than 60 had significantly lower long-term survival compared to the age-matched general population. Patients aged older than 60 had similar survival to the age-matched general population. The findings in this study may help clinicians in selecting appropriate patients for surgery.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bjørnstad JL, Tønnessen T. Koronarkirurgi. Kirurgen [Internet]. 2016 Apr 20 [cited 2018 Feb 05]; Thoraxkirurgi:[About 10 screens]. Available from: http://kirurgen.no/fagstoff/thoraxkirurgi/koronarkirurgi/

- Fiane A, Geiran O, Svennevig JL. Årsrapport for 2016 med plan for forbedringstiltak. Oslo: Norsk Hjertekirurgiregister; 2017. (Annual Report; no. 22).

- Ahmed WA, Tully PJ, Knight JL, et al. Female sex as an independent predictor of morbidity and survival after isolated coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thoracic Surg. 2011;92:59–67.

- Norheim A, Segadal L. Relative survival after CABG surgery is poorer in women and in patients younger than 70 years at surgery. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2011;45:247–251.

- Alam M, Bandeali SJ, Kayani WT, et al. Comparison by meta-analysis of mortality after isolated coronary artery bypass grafting in women versus men. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112:309.

- Arif R, Farag M, Gertner V, et al. Female gender and differences in outcome after isolated coronary artery bypass graft surgery: does age play a role? PLoS One. 2016;11:e0145371.

- Vaccarino V, Abramson JL, Veledar E, et al. Sex differences in hospital mortality after coronary artery bypass surgery: evidence for a higher mortality in younger women. Circulation. 2002;105:1176–1181.

- Filardo G, Hamman BL, Pollock BD, et al. Excess short-term mortality in women after isolated coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Open Heart. 2016;3:e000386.

- Statistics Norway. Forventet gjenstående levetid, etter kjønn og utvalgte alderstrinn 1821–1830 – 2011–2015 [dataset]. In: Ekstern produksjon [Internet]; 2016 Mar 11 [cited 2018 jan 17]. Available from: https://www.ssb.no/statbank/table/05862/tableViewLayout1/?rxid=87d961a5-19ed-45aa-9059-f6cfca7bb4d2

- Wang J, Yu W, Zhao D, et al. In-hospital and long-term mortality in 35,173 Chinese patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting in Beijing: impact of sex, age, myocardial infarction, and cardiopulmonary bypass. J Cardiothorac Vascular Anesthesia. 2017;31:26–31.

- Koch CG, Khandwala F, Nussmeier N, et al. Gender and outcomes after coronary artery bypass grafting: a propensity-matched comparison. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;126:2032–2043.

- Saxena A, Dinh D, Smith JA, et al. Sex differences in outcomes following isolated coronary artery bypass graft surgery in Australian patients: analysis of the Australasian Society of Cardiac and Thoracic Surgeons cardiac surgery database. Eur J Cardio-Thorac Surg. 2012;41:755–762.

- Guru V, Fremes SE, Tu JV. Time-related mortality for women after coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a population-based study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127:1158–1165.

- Miskowiec DL, Walczak A, Jaszewski R, et al. Independent predictors of early mortality after coronary artery bypass grafting in a single centre experience – does gender matter? Kardiologia Polska. 2015;73:109–117.

- Bukkapatnam RN, Yeo KK, Li Z, et al. Operative mortality in women and men undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (from the California Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting Outcomes Reporting Program). Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:339–342.

- Abramov D, Tamariz MG, Sever JY, et al. The influence of gender on the outcome of coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;70:800–805.

- Toumpoulis IK, Anagnostopoulos CE, Balaram SK, et al. Assessment of independent predictors for long-term mortality between women and men after coronary artery bypass grafting: are women different from men? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;131:343–351.

- Shahian DM, O'Brien SM, Sheng S, et al. Predictors of long-term survival after coronary artery bypass grafting surgery: results from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database (the ASCERT study). Circulation. 2012;125:1491–1500.

- Engebretsen KV, Friis C, Sandvik L, et al. Survival after CABG – better than predicted by EuroSCORE and equal to the general population. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2009;43:123–128.

- Enger TB, Pleym H, Stenseth R, et al. Reduced long-term relative survival in females and younger adults undergoing cardiac surgery: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0163754.

- Risum O, Abdelnoor M, Nitter HS, et al. Coronary artery bypass surgery in women and in men; early and long-term results. a study of the Norwegian population adjusted by age and sex. Eur J Cardio-Thorac Surg. 1997;11:539–546.