Because health care resources are limited, it is crucial to differentiate between cost-effective and life-saving treatments and those that are costly and ineffective, or no more effective than cheaper alternatives. Unfortunately, the effectiveness of many new treatments is not fully established when they are implemented in clinical practice, and few are evaluated systematically after their implementation. With the increasing availability of high-quality healthcare registries, the norm should be for regulatory bodies and health care systems to evaluate new treatments by prospectively incorporating reliable variables in existing registries that capture the information that is necessary to reliably evaluate the effectiveness of these new treatments.

Pre-implementation phases of cardiovascular drugs and devices

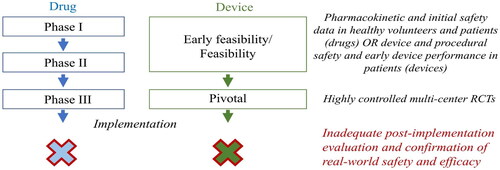

The regulatory framework for testing and approving new treatments for implementation in clinical practice is reasonably robust both in the US and EU (), and typically requires that the safety and efficacy of the treatment is studied in multi-center phase 3 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [Citation1–4]. However, because RCTs are expensive to conduct they are rarely designed to demonstrate conclusive mortality benefits for new treatments but instead rely on composite surrogate outcome measures, some of which may not be what matters most to patients. Even well-conducted RCTs rarely fully establish the effectiveness and safety of a treatment across all relevant patient subsets. To prevent unnecessary harm and ensure that patients who are expected to benefit from the treatment are enrolled, the RTCs often use eligibility criteria that may limit the external validity of its results in everyday clinical practice. Thus, although phase 3 RCTs are essential in the pre-implementation phase and provide some level of comfort that a new treatment is efficacious and safe before it is introduced in clinical practice, they do not fully establish a treatments effectiveness or safety in real-world practice. The uncertainty regarding safety and efficacy is particularly apparent for the few cardiovascular devices that receive approval without being tested in randomized multi-center trials.

Post implementation evaluation of cardiovascular drugs and devices is currently inadequate

Despite the uncertainty surrounding the efficacy, effectiveness, and safety of many new treatments at the time of their implementation, few treatments are evaluated systematically after their implementation, which is likely partly due to the near explicit focus of the regulatory systems in both the US and EU on pre-implementation testing [Citation5]. Others have called attention to the lack of systematic evaluation of drugs and other treatments after their introduction in clinical care, which carries the risk of the medical community failing to identify, or severely delaying the identification of unsafe treatments [Citation5,Citation6]; and suggested that robust and adequately powered post-marketing studies should be required when new treatments are introduced [Citation5]. However, conducting large-scale traditional post-implementation RCTs, the most robust type of study, is very expensive and most likely outside the scope of what is practically possible for most health care systems.

Health care registries allow for inexpensive comparative effectiveness analyses

An increasing number of health care systems now capture a variety of health data through dedicated registries [Citation7]. The Swedish health care system is one example, in which the Swedish Web-System for Enhancement and Development of Evidence-Based Care in Heart Disease Evaluated According to Recommended Therapies (SWEDEHEART) captures a number of patient characteristics, treatments and outcomes; and other registries collect key cardiovascular outcomes, including death. For death and many other important cardiovascular outcomes, the Swedish health care registries have almost complete coverage across the entire country, and patients can readily be linked across registries using their unique national identification number. As such, the Swedish health care system is well equipped to serve as a platform for evaluating the effectiveness of new treatments as they are introduced in clinical practice.

However, although the Swedish health care registries can be trusted to capture outcomes data reliably, there are several other challenges with evaluating treatments in registries. First, it must be possible to reliably define the desired study population, i.e. the patients for whom the treatment is indicated and implemented must be readily identifiable irrespective of whether they actually received the treatment, without substantial selection bias. As relates to Swedish registries, some patient populations can be reliably defined using pre-existing registries (such as patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention) [Citation8] whereas other patient populations cannot [Citation9]. Second, the new treatment must be either randomly assigned to patients in the study population or the probability of receiving the treatment must be predictable based on measured variables within the registry. Failure to meet either of these conditions can render analyses pertaining to the effectiveness of new treatments unreliable.

Improving the reliability of post-implementation registry-based comparative effectiveness analyses by prospective implementation strategies

Both aforementioned limitations of registry studies can be mitigated by prospective measures taken as new treatments are implemented in clinical practice. First, selection bias can be mitigated by the introduction in the registries and quality assurance of new variables that identify the patient population of interest, i.e. patients for whom the new treatment is indicated. Second, treatment preference instruments can be introduced (and quality assured). Such treatment preference instruments can include variables that capture regional or temporal natural variations in the adoption or implementation of the treatment. These treatment preference instruments can then serve as instrumental variables (IVs) in IV analyses, similar to the act of randomization in a randomized trial [Citation10]. Alternatively, the implementation of the new treatment can be done systematically to introduce a non-natural variation in treatment preference that can serve as an IV.

One example of a systematic implementation of a new treatment is the stepwise transition from ticagrelor to prasugrel as the recommended P2Y12 inhibitor for patients undergoing PCI due to acute coronary syndrome that is currently being done in Sweden (NCT05183178) [Citation11]. Specifically, the transition from ticagrelor to prasugrel has been coordinated such that 3 different clusters of health care regions make the transition one after the other with 9 months intervals between each cluster’s transition. Because most patients are treated according to the local recommendation, the preferred P2Y12 inhibitor in the region at the time of percutaneous coronary intervention will be a strong IV. Other forms of systematic variations in treatment preference across regions or time can also be effective prospective IVs, with the most appropriate approach varying according to the type of treatment(s) being studied.

Conclusion

In summary, new treatments are often expensive and their effectiveness for reducing important clinical outcomes in real-world patients is often incompletely understood at their time of implementation. To avoid wasting resources on costly and ineffective treatments for longer periods of time, health care systems should prospectively supplant pre-existing registries with the necessary treatment-specific infrastructure to be able to reliably evaluate the effectiveness of new treatments as they are implemented.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Regulation (EU. 2017/745 Of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 April 2017 on medical devices, amending Directive 2001/83/EC, Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 and Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 and repealing Council Directives 90/385/EEC and 93/42/EEC. OJ L. 2017;117:1–175.

- Regulation (EU. No 536/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 April 2014 on clinical trials on medicinal products for human use, and repealing Directive 2001/20/EC. OJ L. 2014;158:1–76.

- Code of Federal Regulations (CFR). Title 21, Part 312 - Investigational New Drug Application. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. [cited 2023 May 7]. Available at https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/retrieveECFR?gp=1&SID=4e36990a5a57b3d4b4f96bfe6170b59e&ty=HTML&h=L&mc=true&=PART&n=pt21.5.312.

- Code of Federal Regulations (CFR). Title 21, Part 812 - Investigational Device Exemptions. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. [cited 2023 May 7]. Available at https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/retrieveECFR?gp=1&SID=4e36990a5a57b3d4b4f96bfe6170b59e&ty=HTML&h=L&mc=true&=PART&n=pt21.8.812.

- Ray WA, Stein CM. Reform of drug regulation–beyond an independent drug-safety board. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(2):194–201. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb053432.

- Okie S. Safety in numbers—monitoring risk in approved drugs. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(12):1173–1176. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058029.

- Vasko P, Alfredsson J, Bäck M, et al. SWEDEHEART Annual Report 2022. [cited 2023 May 6]. Available at https://www.ucr.uu.se/swedeheart/dokument-sh/arsrapporter-sh.

- The Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry (SCAAR). [cited 2023 May 6]. Available at https://www.ucr.uu.se/swedeheart/start-scaar.

- The Swedish Heart Failure Registry (SwedeHF). [cited 2023 May 6]. Available at http://www.ucr.uu.se/rikssvikt-en/.

- Brookhart MA, Rassen JA, Schneeweiss S. Instrumental variable methods in comparative safety and effectiveness research. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19(6):537–554. doi: 10.1002/pds.1908.

- Omerovic E, Erlinge D, Koul S, et al. Rationale and design of switch swedeheart: a registry-based, stepped-wedge, cluster-randomized, open-label multicenter trial to compare prasugrel and ticagrelor for treatment of patients with acute coronary syndrome. Am Heart J. 2022;251:70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2022.05.017.