Abstract

Objectives. The prevalence of patients with prior stroke is increasing globally. Accordingly, there is a need for up-to-date evidence of patient-related prognostic factors for stroke recurrence, post stroke myocardial infarction (MI) and death based on long-term follow-up of stroke survivors. For this purpose, the RIALTO study was established in 2004. Design. A prospective cohort study in which patients diagnosed with ischemic stroke (IS) or transient ischemic attack (TIA) in three Copenhagen hospitals were included. Data were collected from medical records and by structured interview. Data on first stroke recurrence, first MI and all-cause death were extracted from the Danish National Patient Registry and the Danish Civil Registration System. Results. We included 1215 patients discharged after IS or TIA who were followed up by register data from April 2004 to end of 2018 giving a median follow-up of 3.5–6.9 years depending on the outcome. At the end of follow-up 406 (33%) patients had been admitted with a recurrent stroke, 100 (8%) had a MI and 822 (68%) had died. Long-term prognostic predictors included body mass index, diabetes, antihypertensive and lipid lowering treatment, smoking, a sedentary lifestyle as well as poor self-rated health and psychosocial problems. Conclusions. Long-term risk of recurrent stroke and MI remain high in patients discharged with IS or TIA despite substantial improvements in tertiary preventive care in recent decades. Continued attention to the patient risk profile among patients surviving the early phase of stroke, including comorbidities, lifestyle, and psychosocial challenges, is warranted.

Introduction

The prevalence of patients with prior ischemic stroke (IS) is increasing globally [Citation1]. This is a consequence of a combination of a continued high incidence of IS and transient ischemic attack (TIA) and improvements in survival after first stroke [Citation2]. The improved post-stroke survival is at least partly explained by implementation of efficient acute treatment including reperfusion therapy [Citation3,Citation4] and specialised stroke units [Citation5] combined with adherence to evidence-based clinical guidelines on secondary/tertiary prophylaxis [Citation6].

Increased survival after stroke emphasises the need for up-to-date knowledge of the long-term prognosis including risk of recurrent vascular events and death to ensure the most optimal patient pathway after the early acute phase. The evidence of risk factors for a first stroke is well-established; however, even today considerable uncertainty remains regarding the long-term clinical implications of patient-related prognostic factors in stroke survivors [Citation6]. Hence, more evidence is warranted from well-defined IS/TIA cohorts with complete long-term follow-up. The cohort study of Risk Factors of Recurrent Stroke, Myocardial Infarction and Death in Patients Leaving Hospital with a Diagnosis of Stroke or TIA (RIALTO) was established for this purpose. The study is characterised by broad inclusion criteria, detailed identification of patients’ prognostic profile at baseline, and long-term follow-up.

Materials and methods

Study population and setting

The tax-financed Danish National Health Service guarantees no-cost, partial reimbursement of consumer costs of medical treatment, and equal access to general practitioners and hospitals. Information on the citizens’ vital and emigration status is complete and continuously updated. All Danish citizens are assigned a unique 10-digit Civil Registration Number, which enables unambiguous linkages between the national public registries. Critical and acute care is exclusively provided by public hospitals.

From April 2004 till September 2007, patients admitted to the stroke units of three Copenhagen University Hospitals (Hvidovre, Bispebjerg and Frederiksberg Hospitals) with a diagnosis of IS, intracerebral cerebral haemorrhage (ICH) or TIA were eligible for the study. The current study was restricted to patients diagnosed with IS or TIA. Patients with severe cognitive deficits, dementia or unconsciousness were excluded unless a close relative gave written informed consent on behalf of the patient. Study nurses were engaged in consecutive inclusion of patients for the study. After reviewing medical records for possible inclusion of patients, they approached eligible patients for written and oral information as soon as a neurologist had informed the patient about the diagnosis based on a CT scan or MR scan. Data were collected from medical records and by a structured interview of patients or close relatives.

Patient characteristics

The diagnosis of stroke followed the definition given by the World Health Organisation (WHO): rapidly developed clinical signs of focal (or global) disturbance of cerebral function, lasting more than 24 h. TIA was defined as symptoms lasting less than 24 h.

Education was calculated as years in school combined with years of vocational training in accordance with International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) of the UNESCO. Marital status was categorised as married/living with a partner, widowed, or divorced/single. Patient’s baseline height and weight were measured by the staff at the stroke unit with the patient wearing light clothes and no shoes, and we calculated body mass index (BMI) as kilograms divided by height (in m2). Abuse of alcohol was defined as more than 14 drinks per week in women and more than 21 drinks in men according to the guidelines of the National Board of Health at that time. We calculated pack years of tobacco in current and former smokers with 20 g of tobacco per day in one year giving one pack year. Level of physical activity in leisure time: sedentary/at least four hours of light physical activity per week/at least four hours of vigorous activity per week. Patients were categorised as hypertensive when blood pressure (BP) in the medical records on day 2 or 3 after admission was 140/90 mmHg or higher in non-diabetic patients, and 130/80 mmHg or higher in those with diabetes. Questions about self-rated health (SRH), social isolation, and feeling lonely were identical to those used in population surveys performed by the National Institute for Public Health [Citation7].

Social isolation was examined by the question: “Could you count on getting help from others in case of sickness?” Loneliness was investigated by asking: “Are you ever alone when you would have preferred being with others?”

Baseline data were entered into the web-based Quality Measurement System database of the Unit of Clinical Quality at Bispebjerg Hospital.

Study outcomes

We used first recurrence of stroke, myocardial infarction (MI) and all-cause death as end points of the study until 31 December 2018. The outcomes were analysed both as a composite outcome, i.e. major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE), and as individual outcomes. Information on the outcomes was obtained by record linkage with population-based national administrative registers. Information on stroke and MI was obtained from the Danish National Patient Registry, which contains nationwide prospectively registered information on all hospital contacts [Citation8]. The registry provided individual-level information on admission and discharge, surgical procedures performed, primary diagnosis, and secondary diagnoses at discharge.

Coding of diagnoses followed the International Classification of Diseases version 10 (ICD-10). Data on all cause death was obtained from the Danish Civil Registration System, which holds electronic records of all changes in vital status and migration for the entire Danish population, including changes in address, date of emigration, and date of death [Citation9].

Ethics approval

The regional Ethics Committee (KF 07-00-031/02) and the Danish Data Protection Agency approved the study, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients or a close relative.

Statistical methods

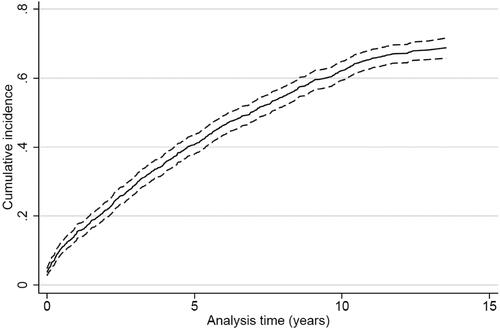

For descriptive data analysis, we present continuous variables as medians and quartile range, and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages. Cumulative incidence proportion curves for the outcomes were constructed. The curves for recurrent stroke and MI were made using the Aalen–Johansen estimator in order to account for the competing risk of death. The association between each of the exposure variables and recurrent stroke, MI, death, and MACE were analysed using Cox regression analysis. Hazard ratios (HRs) were estimated as unadjusted and adjusted for sex, age, and type of index event (IS vs. TIA) using inverse probability of treatment weights (IPTWs). For MI and recurrent stroke, the HRs were estimated as cause-specific, thus censoring at the occurrence of death. Only patients with data available for all assessed covariates were included, in order to ensure that the same study population was included in all analyses.

To account for the explorative nature of the study, we conducted a Benjamini–Hochberg analysis on all the adjusted HRs to see how many of the statistically significant results, using a 5% significance level, retained their significance at a false discovery rate (FDR) of 0.05, 0.1. 0.15 and 0.20. HRs and cumulative incidences are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and all analyses were conducted using Stata 16 (StataCorp, 2019, Stata Statistical Software: Release 16, StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX).

Results

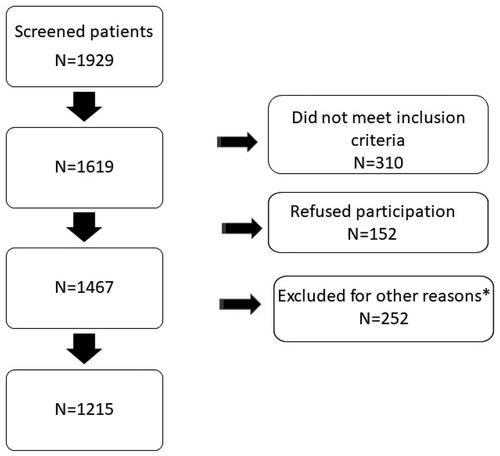

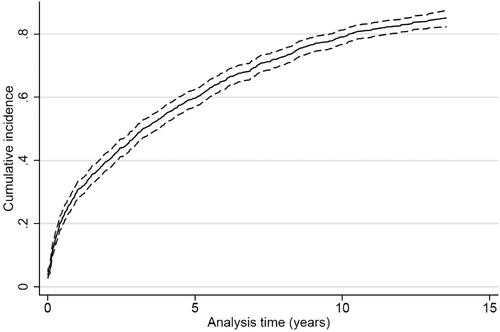

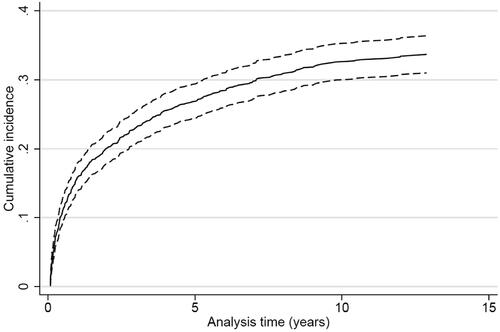

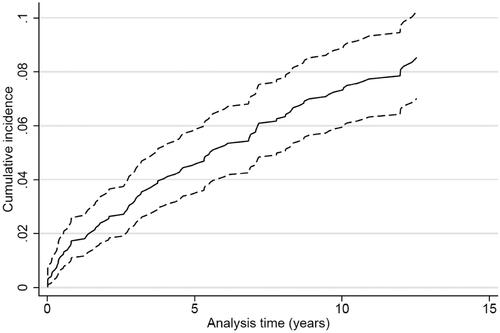

We screened 1929 patients and included 1215 patients with IS or TIA (). Complete data on all variables were available on 1013 patients (83%). Median time to inclusion in the study was nine days (inter-quartile range (IQR) 4–22). In 340 cases (28%), a close relative gave written informed consent to participation on behalf of the patient or assisted the patient in answering the questions of the structured interview. The median follow-up was more than three years for recurrent stroke and more than six years for MI and death (). At the end of follow-up, 406 (33%) patients had been admitted with a recurrent stroke, 100 (8%) with MI, and 822 (68%) were dead (). The majority − 711 patients (59%) – had one event, 289 (24%) had two events and all three events were found in 13 patients (1%). Thus, 393 patients (32%) were alive by the end of 2018 including 202 without recurrent stroke or MI. Cardiovascular risk factors were highly prevalent in the cohort (). At discharge, 717 (59%) were on antihypertensive treatment, 601 (50%) received lipid lowering medication, 1084 (89%) received antithrombotic treatment while 98 (51%) with atrial fibrillation received anticoagulant treatment.

Figure 1. Flowchart. *Fourteen patients had their diagnosis revised, 63 were discharged before contact with study nurse, 83 died, 53 due to cognitive deficits, and 39 for ethical reasons.

Figure 2. Cumulative incidence proportion curve of MACE (recurrent stroke, myocardial infarction and all-cause death) for patients surviving ischemic stroke or TIA (n = 1013).

Figure 3. Cumulative incidence proportion curve of recurrent stroke for patients surviving ischemic stroke or TIA (n = 1013).

Figure 4. Cumulative incidence proportion curve of myocardial infarction for patients surviving ischemic stroke or TIA (n = 1013).

Figure 5. Cumulative incidence proportion curve of all-cause death for patients surviving ischemic stroke or TIA (n = 1013).

Table 1. Adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals of potential patient-related predictors of recurrent stroke for patients surviving ischemic stroke or TIA (n = 1013)Table Footnotea.

Table 2. Adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals of potential patient-related predictors of myocardial infarction for patients surviving ischemic stroke or TIA (n = 1013)Table Footnotea.

Table 3. Adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals of potential patient-related predictors of all-cause death for patients surviving ischemic stroke or TIA (n = 1013)Table Footnotea.

Table 4. Baseline characteristics in 1215 patients with ischemic stroke or TIA.

The patient-related factors with the strongest associations with a higher long-term risk of MACE were short education, smoking (in particular a smoking history >50 pack years), sedentary lifestyle, diabetes, poor SRH, and feeling lonely. In contrast, BMI < 18.5 and lipid lowering treatment at discharge were associated with a lower long-term risk of MACE (). In addition, a low adjusted HR was observed for anticoagulant treatment among patients with atrial fibrillation although it did not reach statistical significance.

Table 5. Adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals of potential patient-related predictors of MACE (recurrent stroke, myocardial infarction and all-cause death) for patients surviving ischemic stroke or TIA (n = 1013)Table Footnotea.

In general, most of these associations persisted when focusing on the individual components of MACE, i.e. recurrent stroke, MI and all-cause death (). However, not all associations reached statistical significance due to the lower number of outcomes and consequently poorer statistical precision. Still, some variation was noted, e.g. BMI >25 was associated with lower risk of all-cause death (), but higher HR point estimates of recurrent stroke and MI ( and ). Furthermore, treatment with lipid lowering medication at discharge was associated with higher risk of MI, but a lower risk of all-cause death ( and ).

The Benjamini–Hochberg analysis revealed, that 19, 22 and 26 of the statistically significant results were retained at an FDR of 0.05, 0.10 and 0.15, corresponding to a corrected significance level of 0.009, 0.020 and 0.036, respectively. All the statistically significant results were retained at a FDR of 0.20.

Discussion

In this long-term follow-up study of patients with IS and TIA, we found notable high cumulative long-term risk of adverse clinical outcomes, including the composite MACE outcome as well as recurrent stroke, MI and all-cause death. The risk varied substantially according to a range of patient-related baseline characteristics of which the vast majority is amenable to intervention. Patients in the RIALTO-study were included from April 2004 till September 2007. By the end of 2018, 68% of patients had died and only 17% survived without stroke recurrence and MI. Although a high cumulative risk of adverse events is to be expected when conducting long-term follow-up of a cohort with a median age of 73 years at baseline, the results indicate that a substantial potential for improved secondary/tertiary preventive care was present. This is emphasised by the low proportions of patients discharged on antihypertensive, lipid-lowering and anticoagulant treatment.

Recurrence, MI, and death

In a meta-analysis reporting the cumulative risk of stroke recurrence from 13 studies performed between 1961 and 2006, the pooled 10-year recurrence rate was 39% [Citation10], quite similar to the recurrence rate of 33% in the present study.

A French meta-analysis based on 58 studies indexed before December 2016 investigating risk of MI and recurrent stroke showed a decreasing MI rate over time as opposed to the apparent quite stable risk of recurrent strokes [Citation11]. The median follow-up was 3.5 years. The risk of MI was below 1.3% per year versus 4.3%/year for stroke recurrence. In the present study, we found similar results regarding MI with 8% of patients suffering a MI during a median of six years of observation, but a higher incidence of stroke recurrence with 33% having a recurrent stroke within a median of 3.5 years. Still, differences in study populations regarding diagnoses of stroke, first-ever or any stroke, and ethnicity complicate direct comparison of these outcomes.

Although post-stroke mortality has declined over the past decades, it remains substantial [Citation12,Citation13]. Results from previous long-term follow-up studies of stroke populations, including from our own study area have shown very high cumulative mortality risks. Hence, the Copenhagen City Heart Study included first-ever stroke patients from 1978 to end of 2001. Of the 2051 included patients, 88% were dead by follow-up in 2007 [Citation14]. Data from the Copenhagen Stroke Study (n = 999) also revealed a 10-year mortality rate of 81% [Citation15]. Participants were included from Bispebjerg Hospital 10 years prior to the initiation of our study. Similar findings have been reported from other settings. In a study of stroke patients in Auckland, New Zealand, from 1981 to 1982, 626 (92%) of patients had died by 21 year follow-up [Citation16]. Likewise, a study from South London including 2625 patients with first-ever stroke between 1995 and 2003, a total of 79% had died by follow-up at the end of 2014 [Citation17].

Our finding of a 68% cumulative all-cause mortality risk within a median follow-up period of 6.9 years among patients discharged from hospital alive after IS or TIA in a more contemporary setting and in a tax-financed health care system with universal coverage is noteworthy as it emphasises that IS and TIA remain associated with a serious long-term prognosis.

BMI, sedentarity, and smoking

The patients’ pre-stroke lifestyle strongly affected post-stroke outcomes. Among the lifestyle factors BMI, low level of physical activity and smoking had the strongest association with the end points in the present study. BMI <18.5 was associated with a 60% higher risk of MACE, whereas BMI ≥25 was associated with a lower risk of death and a borderline significant association with higher risk of stroke recurrence. These findings are similar to those of a Japanese study comparing outcomes after stroke according to level of BMI showing an adjusted HR of death of 2.1 for BMI <18.5, and 0.9 for BMI ≥25, whereas level of BMI was not associated with the risk of stroke recurrence [Citation18].

Obesity is a risk factor for stroke [Citation19,Citation20]; yet, a BMI ≥25 has been associated with a post stroke survival benefit in observational studies [Citation21,Citation22] most pronounced in case of IS. The exact explanations for this so-called obesity paradox remain unclear but may be related to selection mechanisms, i.e. “survival of the fittest”, and differences in subsequent use of appropriate preventive medication [Citation23,Citation24].

In the present study, prestroke leisure physical activity of less than four hours per week was associated with a higher risk of MACE, MI and all-cause death. These findings are in accordance with a recent cohort study on prestroke physical activity among 881 individuals with a median follow-up of three years. Higher levels of total prestroke physical activity as well as work and leisure activity were associated with lower risk of poststroke mortality [Citation25].

Use of tobacco was highly prevalent in the population of RIALTO with only 21% of patients being never smokers. More than 50 pack-years of tobacco was associated with a 25% higher risk of MACE and a 39% higher mortality. A meta-analysis of cohort studies and randomised controlled trials of predictors and impact of smoking cessation after stroke or TIA found that half of patients quit smoking. More severe stroke and intention to quit smoking prior to stroke were associated with smoking cessation. Intensive smoking cessation programs were more successful than in-hospital smoking cessation counselling. Smoking cessation was associated with a lower risk of recurrent strokes, acute myocardial infarction and death [Citation26].

Diabetes

In the present study, diabetes was associated with a 31% higher risk of MACE, a 39% higher risk of death and a more than twofold risk of MI.

In a meta-analysis covering 359,783 patients with IS or ICH diabetes was associated with stroke recurrence in one of three studies and associated with 1-year mortality after IS in one of two studies. The prevalence of diabetes in all stroke patients was 28% with 33% in IS-patients [Citation27]. With the high prevalence of diabetes and evolving diabetes treatment options, efforts to optimise diabetes care should be fundamental in stroke patients.

Self-rated health and socioeconomic factors

Our study shows that mental and social aspects of life are strongly associated with mortality after stroke. Thus, poor/very poor SRH was associated with a 36% higher long-term mortality. A systematic review from 2019 including 51 studies found inconclusive results as to the relation between poor SRH and stroke mortality [Citation28]. Home-based psychoeducational programs as well as family involvement in functional rehabilitation of stroke survivors may be effective in improving SRH [Citation28,Citation29].

In addition, socioeconomic factors, including lower level of education, living alone and social isolation and loneliness were all associated with higher post-stroke mortality in our study. These results confirm and extend findings from previous studies [Citation30,Citation31].

Among interventions aimed at decreasing social isolation and loneliness group interventions with an educational focus or a target population as well as seeking participants’ suggestions to the intervention beforehand have proved successful. Referral to social workers and psychologists may be helpful, but more research is needed on how to best identify and treat social isolation [Citation32].

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of our study included the detailed assessment of a wide range of patient-related and treatment characteristics and the long-term follow-up using high-quality population-based national registries. The study specifically focused on the role of patient-related characteristics, which can easily be assessed at the time of hospital discharge in order to understand the prognostic information that these characteristics may represent in a routine clinical setting and may pragmatically be used to inform health care professionals and patients about the long-term prognosis while at the same time acknowledging that changes in lifestyle, medical care and life circumstances may occur during long-term follow-up.

The limitations included the moderate size of the study population, which implied that the statistical precision was challenged in some of the analyses. In addition, a somewhat simplified approach was needed when adjusting for potential confounding in the multivariable analyses. Hence, we chose to adjust only for age, sex and type of index event in the analyses, even though other potential confounding variables could potentially be at play in some of the studied associations. The presented analyses should therefore not necessarily be interpreted as causal associations. The findings of antihypertensive and lipid lowering treatment being associated with a higher risk of MI are examples of this. These findings are clearly likely to be the result of confounding by indication as there are no biological explanations for these associations [Citation33]. Furthermore, we had no information on adherence with the prescribed pharmacological treatments and life style recommendations during follow-up, e.g. whether target values for BP and lipids were met or whether smoking cessation was upheld. This will likely have biased the associations in a conservative direction. Detailed information on stroke severity and etiology, including NIHSS score or TOAST classification, or TIA characteristics was also not available on the cohort. This limits the ability of our study to provide more accurate prognostic information for specific subgroups which are at higher risk of future cardiovascular events (i.e. recurrent TIAs, capsular warning syndrome) [Citation34,Citation35]. Finally, the characteristics of our study population were for most characteristics comparable with the contemporary national stroke population in Denmark as reflected by the most recent report from the Danish Stroke Register [Citation36]. However, there are also differences, i.e. a higher proportion of smokers and lower proportion of patients on antihypertensive and anticoagulant treatment. These differences may both reflect temporal changes in the risk profile of the general and stroke population as our cohort was recruited in the period 2004–2007 and specific characteristics of the patient population in the catchment area of the hospitals in our study. However, even if the risk profile of our study population is not completely comparable to the average contemporary IS/TIA population, the findings may still be both valid and relevant if we assume that the biological effect of examined factors are the same. This would seem like a reasonable assumption, although we cannot know for sure.

Conclusions

Patients surviving IS and TIA remain at a high absolute risk of adverse long-term outcomes, including recurrent stroke, MI and all-cause mortality despite substantial improvements in rehabilitation and tertiary medical prophylaxis in the last decades. Further efforts are warranted in order to more systematically use readily available information on baseline patient characteristics to ensure effective and targeted post-stroke care.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank study nurse Tove Brink-Kjær for her competent and dedicated work with identification of eligible patients, information and interview of patients and relatives as well as her data collection for this cohort study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Johnson CO, Nguyen M, Roth GA, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(5):439–458. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30034-1.

- Feigin VL, Lawes CM, Bennett DA, et al. Worldwide stroke incidence and early case fatality reported in 56 population-based studies: a systematic review. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(4):355–369. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70025-0.

- Lees KR, Bluhmki E, von Kummer R, et al. Time to treatment with intravenous alteplase and outcome in stroke: an updated pooled analysis of ECASS, ATLANTIS, NINDS, and EPITHET trials. Lancet. 2010;375(9727):1695–1703. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60491-6.

- Goyal M, Menon BK, Van Zwam WH, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet. 2016;387(10029):1723–1731. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00163-X.

- Langhorne P, Ramachandra S, Stroke Unit Trialists’ Collaboration. Organised inpatient (stroke unit) care for stroke: network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;4(4):CD000197. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000197.pub4.

- Pan Y, Li Z, Li J, et al. Residual risk and its risk factors for ischemic stroke with adherence to guideline-based secondary stroke prevention. J Stroke. 2021;23(1):51–60. doi: 10.5853/jos.2020.03391.

- Ekholm O, Hesse U, Davidsen M, et al. The study design and characteristics of the Danish National Health Interview Surveys. Scand J Public Health. 2009;37(7):758–765. doi: 10.1177/1403494809341095.

- Schmidt M, Schmidt SAJ, Sandegaard JL, et al. The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:449–490. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S91125.

- Mainz J, Hess MH, Johnsen SP. The Danish unique personal identifier and the Danish Civil Registration System as a tool for research and quality improvement. Int J Qual Heal Care. 2019;31(9):717–720.

- Mohan KM, Wolfe CDA, Rudd AG, et al. Risk and cumulative risk of stroke recurrence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2011;42(5):1489–1494. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.602615.

- Boulanger M, Béjot Y, Rothwell PM, et al. Long-term risk of myocardial infarction compared to recurrent stroke after transient ischemic attack and ischemic stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(2):e007267. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007267.

- Schmidt M, Jacobsen JB, Johnsen SP, et al. Eighteen-year trends in stroke mortality and the prognostic influence of comorbidity. Neurology. 2014;82(4):340–350. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000062.

- Yafasova A, Fosbøl EL, Christiansen MN, et al. Time trends in incidence, comorbidity, and mortality of ischemic stroke in Denmark (1996–2016). Neurology. 2020;95(17):e2343–e2353. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010647.

- Boysen G, Marott JL, Grønbaek M, et al. Long-term survival after stroke: 30 years of follow-up in a cohort, the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Neuroepidemiology. 2009;33(3):254–260. doi: 10.1159/000229780.

- Andersen KK, Olsen TS. One-month to 10-year survival in the Copenhagen Stroke Study: interactions between stroke severity and other prognostic indicators. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;20(2):117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2009.10.009.

- Anderson CS, Carter KN, Brownlee WJ, et al. Very long-term outcome after stroke in Auckland, New Zealand. Stroke. 2004;35(8):1920–1924. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000133130.20322.9f.

- Crichton SL, Bray BD, McKevitt C, et al. Patient outcomes up to 15 years after stroke: survival, disability, quality of life, cognition and mental health. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87(10):1091–1098. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2016-313361.

- Kawase S, Kowa H, Suto Y, et al. Association between body mass index and outcome in Japanese ischemic stroke patients. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17(3):369–374. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12713.

- Strazzullo P, D'Elia L, Cairella G, et al. Excess body weight and incidence of stroke: meta-analysis of prospective studies with 2 million participants. Stroke. 2010;41(5):e418–e426. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.576967.

- Kurth T, Buring JE. Body mass index and risk of stroke in women. Cardiol Rev. 2006;23(3):29–32.

- Oesch L, Tatlisumak T, Arnold M, et al. Obesity paradox in stroke – myth or reality? A systematic review. PLOS One. 2017;12(3):e0171334. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171334.

- Akyea RK, Doehner W, Iyen B, et al. Obesity and long-term outcomes after incident stroke: a prospective population-based cohort study. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2021;12(6):2111–2121. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12818.

- Doehner W, Clark A, Anker SD. The obesity paradox: weighing the benefit. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(2):146–148. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp339.

- Steinberg BA, Cannon CP, Hernandez AF, et al. Medical therapies and invasive treatments for coronary artery disease by body mass: the “obesity paradox” in the get with the guidelines database. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(9):1331–1335. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.06.019.

- Mediano MFF, Mok Y, Coresh J, et al. Prestroke physical activity and adverse health outcomes after stroke in the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Stroke. 2021;52(6):2086–2095. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.032695.

- Noubiap JJ, Fitzgerald JL, Gallagher C, et al. Rates, predictors, and impact of smoking cessation after stroke or transient ischemic attack: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2021;30(10):106012. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2021.106012.

- Lau LH, Lew J, Borschmann K, et al. Prevalence of diabetes and its effects on stroke outcomes: a meta-analysis and literature review. J Diabetes Investig. 2019;10(3):780–792. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12932.

- Araújo ÉdF, Viana RT, Teixeira-Salmela LF, et al. Self-rated health after stroke: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Neurol. 2019;19(1):221. doi: 10.1186/s12883-019-1448-6.

- Chang AK, Park YH, Fritschi C, et al. A family involvement and patient-tailored health management program in elderly Korean stroke patients’ day care centers. Rehabil Nurs. 2015;40(3):179–187. doi: 10.1002/rnj.95.

- Che B, Shen S, Zhu Z, et al. Education level and long-term mortality, recurrent stroke, and cardiovascular events in patients with ischemic stroke. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(16):e016671. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.016671.

- Liu Q, Wang X, Wang Y, et al. Association between marriage and outcomes in patients with acute ischemic stroke. J Neurol. 2018;265(4):942–948. doi: 10.1007/s00415-018-8793-z.

- Ferreira G, Walters A, Anderson H. Social isolation and its impact on the geriatric community. Top Geriatr Rehabil. 2021;37(3):191–197. doi: 10.1097/TGR.0000000000000314.

- Bosco JLF, Silliman RA, Thwin SS, et al. A most stubborn bias: no adjustment method fully resolves confounding by indication in observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(1):64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.03.001.

- Foschi M, Pavolucci L, Rondelli F, et al. Capsular warning syndrome: features, risk profile, and prognosis in a large prospective TIA cohort. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2023;52(2):218–225. doi: 10.1159/000525954.

- Foschi M, Pavolucci L, Rondelli F, et al. Prospective observational cohort study of early recurrent TIA: features, frequency, and outcome. Neurology. 2020;95(12):e1733–e1744. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010317.

- Danish Stroke Register. Annual report 2022. Danish; 2023. Available from: https://www.sundhed.dk/content/cms/69/4669_danstroke_aarsrapport-2022_offentlig-version_201130.pdf