ABSTRACT

This paper addresses one of the most fundamental, but least considered, questions in housing research: how should we ultimately evaluate housing outcomes? Rejecting the fact vs value dichotomy so dominant in the social sciences, this paper draws on the work of Amartya Sen and Hilary Putnam to critically assess the ethical assumptions behind three commonly adopted “informational spaces” for evaluating housing outcomes: economic, subjective and “objective” metrics. It argues that all three fail to account for the plurality of goods that individuals have reason to value and the fallibility of human judgement. As an alternative, it proposes that housing outcomes should be ultimately evaluated in terms of people’s “housing capabilities” - the effective freedoms that people have in their homes and neighbourhoods to do and feel the things they have reason to value – which should generally be determined through a bottom-up process of democratic deliberation involving critical and expert perspectives.

Introduction

Whether we consider instances of housing policy/practice to represent progress or not depends upon how we define “success”, an intensely value-base judgement. Take Housing Market Renewal as an example. Between 2002–2011, UK central government spent £2.2 billion pounds and demolished 10,000 houses in an attempt to renew failing housing markets in the North of England (Wilson Citation2013). Was the programme a success? Well, it depends on how we define “success”. The evaluative framework used by the government was dominated by two metrics – house prices and vacancy rates – and based on these, the project arguably represented progressFootnote1. However, it is highly questionable whether this was an ethically reasonable evaluative framework in the first place. For one thing, the framework did not consider the financial well-being of renters and aspiring home-owners who would, if anything, have suffered from increased house prices (or associated rents). Nor did it consider the financial well-being of those owners whose homes were demolished, who faced a £35,000 average shortfall between the compensation received and the cost of a suitable alternative property (Cole and Flint Citation2007).

Besides judging the success of a regeneration initiative or policy intervention, the evaluation of housing outcomes takes place at a national scale through the periodic monitoring of affordability metrics and homelessness statistics, and at an organizational scale through the use of “key performance indicators” (KPI’s) and social impact measurement (Wilkes and Mullins Citation2012). We must also adopt a particular definition of housing justice or progress when evaluating levels of housing (in)equality. Some, if not most, of us would consider inequality in housing outcomes a matter of injusticeFootnote2, but inequality of what (Sen Citation1980)? Inequality of housing costs? Inequality of social, economic and cultural capital? Similarly, if we are to identify instances of housing poverty or deprivation, we must also ask “deprivation or poverty of what?” There is no commonly accepted definition but housing deprivation is commonly viewed through the lens of physical housing conditions (e.g. Decent Homes Standard, Over-crowding) and affordability.

All of the instances above require us to decide upon an evaluative framework for defining progress. But what type of metric(s) or informational space should we use? And who decides? Drawing largely on the work of Amartya Sen and Hilary Putnam, this paper addresses the normative question of how we should ultimately evaluate housing outcomes. The next section starts by laying out the epistemological foundations of the paper, arguing for “classical realist” approach which is both anti-foundationalist and anti-relativist. Section three then critically assesses three commonly adopted “informational spaces” for evaluating housing outcomes – economic, subjective and “objective” – tracing their philosophical roots, and reviewing ethical arguments for and against each in the context of housing. Section four then proposes that housing outcomes should be ultimately evaluated in terms of people’s “housing capabilities” which should generally be determined through a bottom-up process of democratic deliberation. The final section concludes.

Speaking Ethically (And epistemologically)

In discussions of housing policy (at HSA, ENHR, etc.), it would be unsurprising to hear someone challenge a statement, not by saying that the statement in question is false, or the arguments offered in its favour are not good ones, but by asking in a certain tone of voice, “Is that supposed to be a fact or a value judgment?”. The implication being that if it is a value judgement then it is simply “subjective”, and a further implication being that if it is “subjective” then “my value judgments are just as good as yours” – that is, the whole notion of better and worse reasons, not to say correctness and incorrectness, does not apply. In this scenario – adapted from Hilary Putnam (Citation2003) – facts are posited as being objectively true and capable of being objectively warranted, in direct opposition to values which are purely subjective and therefore lie outside the sphere of reason.

This dichotomy between fact and value has been hugely influential in the social sciences, yielding a whole set of accompanying dichotomies; between objective vs subjective, positive vs normative economics and descriptive vs prescriptive analysis. Hilary Putnam (Citation2002) traces the roots of the fact vs. value dichotomy back to the logical positivists but more recently, Milton Friedman, took great pride in the objectivity of positive economics, “Positive economics is in principle independent of any particular ethical position or normative judgments. [… It] is, or can be, an ‘objective’ science, in precisely the same sense as any of the physical sciences”. (Friedman Citation1953, 4)”. And although most economists today have moved on from logical posivitism, the fact/value dichotomy still underlies their beliefs and intended practice (Walsh Citation2003).

“Value-neutrality” is also prized by those policymakers, practitioners and consultants involved in evaluation, who are encouraged to remove themselves from ethical debates by viewing the policymaking process as two distinct stages: first, the democratically elected politician makes the value-based judgement of what the objectives of a programme or policy should be; second, the evaluator (be it an academic or research consultant) factually records the extent to which these objectives have been fulfilled.

The problem with such a distinction, however, is that fact and value judgements are inherently entangled. As Kemeny (Citation1984), Sen (Citation2009), Putnam (Citation2002, Citation2003) and countless others have demonstrated, value-based judgements pervade positive economics and the evaluation of housing outcomes more generally. They are there in the use of “thick ethical concepts” (Williams Citation1985) like “affordable”, “appropriate”, ”efficient”, “optimal” and “utility” which all contain both a factual and normative component (when we say that housing is “unaffordable”, we are essentially saying that people cannot afford a “reasonable” standard of housing on a “reasonable” proportion of their income where, in both cases, defining “reasonable” relies on a value judgement). They are there in the recommendation or disapproval of particular polices (such as increasing housing supply) or the (implicit) endorsement of particular evaluative metrics such as life satisfaction, the 30:40 affordability ratio or GDP per capita. Even the choice of p-value involves an epistemic value-based judgement that involves weighing up the risk of type one and type two errors (Reiss Citation2017).

None of the above will be new to readers of this journal. Social constructionists like Jacobs and Manzi (Citation2000), Kemeny (Citation1984), and Clapham (Citation1997) have been making this argument for decades, demonstrating, for example, how the value-based judgements that lie behind housing research, policy and practice are shaped by power-structures, with neo-liberal housing regimes advancing consumerist values at the expense of equality and sustainability (Clapham Citation2018, Chapter 11). Thus, it would be remiss to say that values have not been discussed in housing research. They have.

However, after pointing out that values are unavoidable in housing research, social constructionists consistently stop short of discussing which values housing policy, practice and research ought to advance. This leads to an incidental and unholy alliance against normative reasoning between positivists and social constructionists, both of whom hold (or at least don’t argue against) the view that because value-based judgements are subjective, it is not possible to say that one value-based judgement is more reasonable than another. Bo Bengtsson noted the absence of normative reasoning in 1995 (Citation1995: 123),

“Markets and politics are in the centre of most normative discussions on housing policy. They are also the focus of housing research. Consequently, one would expect housing researchers to have important things to say in policy matters. Nevertheless, when it comes to normative conclusions some housing researcher turn mute, while other candidly declare their personal position. It is sometimes amazing how social scientists, who would feel obliged to justify, page after page, the slightest methodological irregularity, seem to find it impossible to argue on normative matters in scientific terms.”

And there is nothing to suggest that anything has changed in the intervening 25 years. As Fitzpatrick and Watts (Citation2018, 225) recently noted,

“With some notable exceptions, there is scant theoretical attention paid to these ‘ought’ questions in housing studies, with unexamined values embedded more or less across the board in a largely taken-for-granted fashion…. Where normative issues are overtly addressed it is generally in a fairly shallow and unsophisticated manner”

Faith in the Power of Reason

If we are to reason about values – as this paper seeks to do – then we need an alternative epistemology that accounts for the position-dependency of all value-based judgements without lapsing into the strong moral relativism of social constructionism which holds that one statement can never be more valid than another. It is here that we turn to the thinking of the Hilary Putnam and Amartya Sen, who although coming from different philosophical tradition – Sen associated with a value-pluralist critique of neo-classical economics and Putnam associated with the classical pragmatism of John Dewey – both occupy positions which are largely complementary, dovetailing at various points (e.g. Walsh Citation2003; Putnam Citation2002, Citation2008; Sen Citation2005).

Following other social constructionists and anti-foundationalists, both accept that it is simply impossible to look at the world independently of where we stand (Putnam in Nussbaum and Sen Citation1993, 148; Sen Citation2009, 156) leading them to dismiss the possibility of achieving essentialist or transcendentalist “theories” of truth, knowledge or justice. For the anti-foundationalist philosophers such as Foucault, Rorty and Derrida, once we recognize this, we have no choice but relativism. For them, metaphysical realism represents vital foundations for our beliefs about the world and its contents (Putnam Citation1990, 20), and without these “foundations”, there is no way of saying that one normative (or factual) statement is more valid than another. Channelling the relativism of Foucault (1994), Chris Allen (Citation2008, 197) therefore rejected the call to propose an alternative course of action when criticizing Housing Market Renewal, arguing that “those who work in the sphere of thought should not be obliged to come up with ‘practical alternatives’”.

Not so for Putnam and Sen. They dismiss the significance of metaphysical realism, arguing that to discuss ethics in terms of ontology is deeply misguided (Sen Citation2009, 41). “To identify that metaphysical tradition with our lives and our language” (Putnam Citation1992, 124) argues “is to give metaphysics an altogether exaggerated importance”. More than misguided, it is positively dangerous for academia to vacate the realm of reasoned (normative) debate on ontological grounds and leave it open to “post-truth” demagogues like Erdogan and Trump. “The view that all the left has to do is tear down what is, and not discuss what might replace it” as Putnam ([1992] Citation1995, 130) goes on “is the most dangerous politics of all, and one that could easily be borrowed by the extreme right”.

For Putnam and Sen, the aim of philosophy in general, and ethics in particular, should not be infallibility or a set of eternal, idealized, abstract theoretical truths – as both the foundationalists and relativists assumed – but the progression of practical problems which are situated in particular contexts. In place of “metaphysical realist” understandings of objectivity, Putnam and Sen both argue in favour of a classical realist “common sense” position which understands “objectivity” to be linked to the ability to survive challenges from informed scrutiny coming from diverse quarters (Sen Citation2009, 45). Amartya Sen’s idea of (trans-) positional objectivity (Sen, Citation1993), for example, holds that if people from a range of social positions all agree upon a particular statement – such as “homelessness is unjust”- then we can consider that statement to be “trans-positionally objective”. This is not a metaphysical “rule” – there are undoubtedly times in history after all when an argument has turned out to be right despite being advanced by only a “crazed” minority, even a broken clock is right twice a day – but a fallible rule of thumb derived from historical experience. Shorn of any metaphysical proof, Sen and Putnam both rely on “a sort of cultivated naivete´” (Putnam Citation1994, 283), or democratic faith in the power of reason and the possibility of progress, as Hilary Putnam (Citation2008, 387) summarizes;

What Deweyans possess is the ‘democratic faith’ that if we discuss things in a democratic manner, if we inquire carefully and if we test our proposals in an experimental spirit, and if we discuss the proposals and their tests thoroughly, then even if our conclusions will not always be right, nor always justified, nor always even reasonable – we are only human, after all – still, we shall be right, we will be justified, we will be reasonable more often than if we relied on any foundational philosophical theory, and certainly more often that if we relied on any dogma, or any method fixed in advance of inquiry and held immune from revision in the course of inquiry.

The implications of adopting this classical realist position for the remainder of the paper are not especially radical. Once we recognize that there is no metaphysical difference between fact and value and therefore no methodological difference between morality and science (Putnam Citation2017, Chapter 4), it simply means that we should subject value-based normative debates to the same (self-)critical reasoning as we would do when deliberating the causes of housing unaffordability or the drivers of homelessness.

Three Frameworks for Evaluating Housing Outcomes

Broadly speaking, there are three types of metric most commonly used to evaluate housing outcomes: economic metrics which are rooted in welfarism; subjective metrics derived from utilitarianism which require the subject themselves to judge their own well-being; and “objective” or “expert-defined” metrics which judge an individual’s housing outcomes according to some uniform, commonly agreed standard. Example of these three metrics is given below.

Most housing policy and practice evaluations do not rely on only one form of metric. For example, the two main metrics used to evaluate Housing Market renewal were “objective” (vacancy rates) and economic (house prices) (Leather and Cole Citation2009), and other regeneration scheme evaluations, such as that of Rayner’s Lane in London, have also included subjective metrics (Provan, Belotti, and Power Citation2016). Below, I briefly review the ethical arguments for and against each of these metrics before returning to Putnam and Sen to see what they have to say about how we should evaluate housing outcomes.

Economic Metrics and Welfarism

We can think of two types of value-based judgements in relation to economic metrics. First, there is the choice between different economic metric. Choosing one economic metric over another inevitably involves a value-based judgement about whose economic welfare to prioritize. If we use house prices as a positive evaluative metric (as in HMR, for instance), then we are clearly prioritizing the economic welfare of home-owners over renters as, for the latter, house price growth is likely to equate to higher rents and/or greater difficulty in achieving home-ownership.

Then, there are the ethical arguments for and against using economic metrics in general. On the plus-side, economic measures respect individual freedom to choose, and although economic wealth is not a good in itself, it tends to translate into other goods. If housing costs are more affordable relative to income, then individuals are less likely to experience housing stress (Meen Citation2018), and will be in a stronger position to demand greater security of tenure, and greater control over their homes.

However, economic metrics also have major ethical limitations. To appreciate these, it is perhaps worth briefly remembering their utilitarian foundation. Historically, the debate amongst economists has been about how best to measure happiness rather than about whether happiness is the only thing that matters. For the founders of modern economics (e.g. Francis Edgeworth, W.S. Jevons, Jeremy Bentham) the ultimate goal was to measure happiness directly. However, economists gradually departed from this aim, and placed increasing faith in choice behaviour (or “revealed preferences”) as a proxy for happiness (Read Citation2007).

According to welfarism (Sen Citation1979), the fundamental value of anything is equivalent only to what people are willing to pay for it. If people are willing to pay an extra £1000 per annum to increase their lifespan by 6 months (through, for instance, paying for better healthcare), and they are also willing to spend an extra £1000 per annum for a spare room, then both of these goods are of equivalent value (See Cheshire Citation2018 for example of this logic). The value of something, indeed, anything, is equivalent only to the happiness it brings, which in turn, is equivalent what people are willing to pay for it.

However, there are a number of factual and ethical weaknesses with the logic posited above. The major factual weakness is that improvements in economic metrics – and by extension, the satisfaction of individual preferences – does not always lead to an increase in happiness. Individuals adapt to the improvement in living conditions (e.g. Nakazato, Schimmack, and Oishi Citation2011), and judge their living conditions relative those people around them (their “reference group”) (e.g. Bellet Citation2017). Thus, the relationship between economic resources and happiness will vary between social groups; a two-bedroom house containing five family members is likely to be a source of shame in the UK but the same house may afford prestige in some developing countries.

The relationship between economic resources and happiness will also vary according to mental and physical health: an individual with severe physical disabilities is likely to need much more expensive housing than someone who is fully able to achieve equivalent levels of subjective well-being. In Sen’s terms, different individuals and societies have different “conversion factors” for turning resources into well-being (Sen Citation1992, 19–21, 26–30, 37–38). And, as the early economists recognized (Read Citation2007), the conversion rate will also vary according to one’s income level. An extra pound is going to bring more happiness to someone earning minimum wage than to a millionaire as income has a diminishing effect on happiness (Clark, Frijters, and Shields Citation2008).

Subjective Metrics and Utilitarianism

Partly due to limitations of economic metrics stated above, there has been something of a shift back to Bentham’s ideal of measuring happiness directly. “Customer satisfaction” is one of the key indicators used to evaluate the performance of UK Housing Associations in the Sector Scorecard,Footnote3 and subjective judgements about financial stress have been used to inform the development of economic affordability metrics (Meen Citation2018). Moreover, the UK Treasury’s Citation2018 “Green Book”, the “rulebook” of UK policy evaluation, explicitly states that economic appraisal should be based on the utilitarian principles of welfare economics (Treasury, H. M. S., Citation2018: line 2.3), prioritizing economic and subjective well-being metrics.

In one sense, subjective well-being is a more appropriate informational space to evaluate housing outcomes, as happiness is something which people value in itself, as opposed to money which only has instrumental value. However, people have good reason to value other things than happiness. Most of us would condemn racist social housing allocation policies regardless of their effect on societal well-being. Subjective and economic indicators, both rooted in utilitarianism, are ethically deprived because they fail to recognize that certain things can be morally right or wrong, regardless of their effects on “utility”.

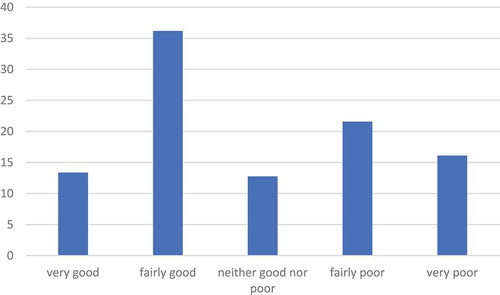

The second major ethical limitation of focussing on subjective metrics when evaluating housing outcomes is that we privilege those with high expectations at the expense of those with low expectations. Peoples’ preferences and what they judge to be the necessities of life depend on what they, and those people around them, have experienced in the past (see Nakazota et al., Citation2011; Bellet Citation2017). below, for example, shows that almost half of the people whose homes failed the Space Standard in 2008Footnote4 rated the size of their living space “very good” or “fairly good”. Deprived persons’ housing expectations can be stymied by powerful interests, meaning that instead of rebelling against injustice, they may lie down and accept their lot. Take this older ex-homeless man who was asked how he felt about only being offered a 5-year fixed term tenancy instead of a lifetime tenancy (which is the norm with social housing in the UK),

I didn’t really take that much notice to tell the truth, because it was – like I said, I was so grateful to have a roof over my head, especially after being there [hostel] so long … I didn’t really think that much of it because knowing that I needed a roof over my head I just accepted, right, what was on the plate as such. (Fitzpatrick and Watts Citation2017, 1031)

“Objective” (Or “Expert-defined”) Metrics and Objective List Theories

Many of the ethical limitations of subjective metrics can be addressed through the use of objectiveFootnote5 metrics such as rooms per person, and the Decent Homes Standard. Objective metrics are too heterogenous to be associated with one particular theory of justice, but they are probably most closely related to Aristotelian objective-list theories of well-being which specify goods, actions, or freedoms which universally constitute the good life (Rice Citation2013).

By using a commonly agreed standard of measurement, objective metrics avoid the problem of adaptive preferences as everyone’s housing conditions are measured on the same scale.

Objective metrics also allow for us to classify certain polices as unjust, regardless of their consequences: we can rank different local authorities on the inclusiveness of their allocation policies, and we can judge unhealthy living conditions to be inadequate even if the tenant is satisfied with them as a result of having known nothing better.

However, by taking the power of judgement away from individual citizens, and concentrating it in the hands of the evaluator or regulator, we run the very serious risk of undue paternalism: that the organization doing the evaluating will impose their vision of the good life onto the organization or citizens who may have an entirely reasonable but rivalling conception of the good life. A prime example of this relates to over-crowding. The ethnographer, Pader (Citation1994, Citation2002) has demonstrated how overcrowding regulations in the USA have been used to impose a Western-centric view of how space should be used on immigrant populations. This is vividly illustrated in the following quotation from a housing attorney interviewed by Pader (Citation2002, 301);

I never really thought about how I lived until I was an attorney working city cases where the state was moving to take kids away from their families. One case had a very young social worker, 24, and she was just outraged that a grandmother was sleeping in the same room with her grandchild. [The social worker] said it’s “inappropriate and we have to intervene in this family and take this child out. How could you have two generations … sleeping in the same bedroom … It’s totally inappropriate.

If a family’s economic circumstances leave them with no choice but to share a room, then that is arguably a matter of injustice. But in some cultures, people reject the option of having a separate bedroom because they value spatial proximity or “skinship” over privacy. As a Mexican woman who moved to Los Angeles in the late 1940s said to Pader (Citation1993, 129),

We do things differently. They don’t understand that we all share rooms, that it’s better for the children to learn to share and not just think about themselves. I see so many Americans living on their own, and I think how lonely they must be.

A More Reasonable Framework for Evaluating Housing Outcomes?

Returning to the perspective of Sen and Putnam, we can see that all of the ethical flaws discussed above with welfarism, utilitarianism and objective list-theories are rooted in the same failure to recognize the position-dependency and fallibility of human judgement.

In the same way that the logical positivists claimed to have an objective “view from nowhere” when describing and understanding the world, so these universalist “theories” of justice presuppose a uniformity of principles upon which all “rational” persons can agree. Welfarism, utilitarianism and objective list theories all share a “monological” form of moral reasoning which proceeds from the standpoint of the “rational” person, defined in such a way that differences among concrete selves become quite irrelevant (Benhabib Citation1986, 300). For the neo-classical economist, every “rational” person should agree that justice equates to economic resources; for the utilitarian, the “irrational” person is one who acts against their own subjective well-being out of a sense of duty, and for the social worker in Pader (Citation2002) it was objectively wrong for a granddaughter to share a room with her grandmother. These rationalist theories of justice – welfarism, utilitarianism, objective list theories – are all built on the assumption that the moral philosopher has been able to access some higher form of reasoning, some objective “view from nowhere” (Nagel Citation1986), that “irrational” others who disagree have not yet reached.

In their search for a universal, reductive formula of justice, these rationalist theories belie the irreducible plurality of goods and the conflict and uncertainty that is inherent in the pursuit of progress. Different people value, and have reason to value, different goods and often these goods conflict. Society may have good reason to prioritize the capability to have an extra year’s life expectancy over the capability to have a spare room, even if the willingness to pay metrics suggest both are of equal value.

Putnam and Sen, by contrast, adopt a more open, and pluralist stance, which has been most concretely manifested in the form of the capabilities approach. Advanced most notably by Amartya Sen (e.g. Sen Citation2009) and Martha Nussbaum (e.g. Nussbaum Citation2011), and endorsed by Putnam (Citation2002, Citation2008), the core claim of the capability approach is that judgements about justice or equality, or the level of development of a community or country, should focus ultimately on the effective opportunities that people have to lead the lives they have reason to value – their capabilities.

A key virtue of the capabilities approach is that it accounts for the plurality of goods which individuals have reason to value, including both means and ends (or “agency” and “well-being” in the conceptual terms of Sen Citation1985). It accounts for the intrinsic importance of happiness, as having the effective freedom to do the things that one has reason to value will generally enhance one’s happiness. But, by allowing people to decide upon the effectives freedoms they value, it also accounts for the fact that certain freedoms can be reasonably considered right or wrong regardless of their consequences. It allows for the fact that someone may want, in principle, to remain near their mother with severe dementia, even if neither party is any happier or economically better-off for it (subjective metrics and economic metrics, in contrast, would consider such a state of affairs as sub-optimal). It allows for the fact that not everyone wants a home that meets the Decent Homes Standard, and that some people are quite content with having a house that is technically over-crowded (some objective metrics would see both as obstacles to progress).

By focussing on people’s effective opportunities to do things rather than whether they do them or not, the capabilities approach also accounts for the fallibility of decision-makers and evaluators, thus guarding against undue paternalism. Whereas an “objective” metric focussing on human functionings might consider an adolescent to be impoverished if they shared a bedroom, the capabilities approach would only consider them impoverished if they did not have the “effective freedom” to a room of their own.

The emphasis on “effective” freedoms is also crucial. A common argument used by libertarians to justify dire market outcomes is that because the individual “chose” to live in a room without windows, or “chose” to work on a zero-hours contract, that outcome should be considered just because it resulted from a voluntarily market transaction between a willing buyer and willing seller. For the capabilities approach, however, it is not sufficient that the transaction was voluntary, both transacting agents must also have had a “sufficiently” wide range of options (or “capabilites”) to choose from for that transaction to be considered just (Varoufakis Citation2002–2003).

Despite its ethical merits, there have been few attempts to actually evaluate housing outcomes using capabilities as the primary informational space (Clapham, Foye, and Christian Citation2018), although there has been a recent uptick (Haffner and Elsinga Citation2019; Tanekenov, Fitzpatrick, and Johnsen Citation2018). This neglect maybe borne partly out of ignorance, but the impracticality of the capabilities approach must also be a significant factor (Robeyns Citation2006). It can be extremely difficult to measure an individual’s effective freedoms, as you must measure all the options potentially open to an individual. Ascertaining whether someone would have access to an adequately sized home if they wanted is much more difficult than calculating the number of rooms per person. For this reason, researchers attempting to measure capabilities on a large-scale basis often just end up measuring functionings (see Coates, Anand, and Norris Citation2013 for an example of this applied to housing).

It is also unclear the extent to which the capabilities approach can capture the nuance, subtlety and passivity that characterizes people’s relationships with their home. The capabilities approach works well for substantive freedoms that can be discretely separated out and defined – the freedom to green space or cook one’s meals or to have a spare bedroom – but there are a lot of senses and feelings that people value from home such as “homeliness”, “security” and “the ability to be themselves” which cannot be neatly “pigeon-holed and padlocked” into “effective freedoms”. As Peter King (Citation2017, 18) argues;

“Housing does not actively engage us. It settles us, calms us, hides us and teaches us not to worry about what is outside. Housing works best when we do not notice our need of it. Housing is fulfilment and so the creation of complacency”

This chimes with G.A. Cohen’s critique of the capabilities approach for espousing an all too `athletic’ image of the human deriving happiness only from what they can do (Cohen Citation1993, 24±5), and ignoring the many passive ways in which humans derive happiness. In light of the above, there may be a good reason to expand the definition of capabilities in the context of housing to encompass “the effective freedoms that people have in their homes and neighbourhoods to do and feel the things they have reason to value.”

When it comes to the process of developing a list of capabilities, Sen and Putnam (following Dewey) both make an “epistemological defense of democracy”. Because every observation is made through one’s own particular lens, and is therefore fallible, it is wrong for evaluators to presuppose that every rational person should think the same way, or values the same capabilities, as them. For a set of capabilities to adequately reflect the diversity of values – or to be “positionally-objective” – it needs to be developed from the bottom-up; immersed rather than detached from the community in question (Nussbaum and Sen Citation1987, 308).

The epistemological defence of democracy is particularly valid when applied to value judgements as these are inherently “perspectival” in a way that factual judgements are not (Anderson Citation2003). It makes sense for a neighbourhood to be perceived as downtrodden and derelict by one group of people, but homely and secure by another. It does not, however, make sense for one group to say that “2 + 2 = 5” and another group to say “2 + 2 = 6”. Moreover, those value-based judgements derived from ascriptive identities – such as prioritizing “local people” when allocating social housing – are necessarily perspectival since they are defined through contrast with outgroups (Anderson Citation2003).

Whilst giving weight to the everyday knowledge of the citizen, we should not consider their preferences and values to be sacred. Individuals and communities can be unreasonable, holding views which are stubbornly racist, sexist, selfish, xenophobic, homophobic and intolerant of others, their opinions structured by the currents of power which shape and distort housing preferences (e.g. Gurney Citation1999) and reasoning processes (e.g. Flyvberg Citation1998).

Sen has been elusive in specifying an ideal process for deciding capabilities but if we bring together his thinking, we can start to picture a process that resembles deliberative democracy (Crocher, Citation2006). Broadly defined, deliberative democracy refers to the idea that legitimate law-making issues from the public deliberation of citizens (Bohman and Rehg in Bohman, Citation1997). Whereas representative or direct democracy gets people to express their values simply through voting (for example, on whether to regenerate an estate or not); deliberative democracy gets people to explain and justify their point of view to others, especially those with conflicting viewpoints. Whereas direct democracy takes people’s opinions and values as given, deliberative democracy gets people to critically reflect on their values in recognition that all individuals are capable of being unreasonable, and will therefore benefit from being exposed to external critical perspectives. Deliberative democracy recognizes the inherently political and fallible nature of collective decision-making, emphasizing the ability of individuals to reason with each other, find common ground, or agree to disagree in which case decisions are typically made through a majority vote.

As well as engaging with diverse perspectives, deliberation may also involve experiencing different environments. For someone living in a poorly lit, and ill-proportioned home, it may require them to experience a well-designed home to realize what physical aspects of their built environment they value most. The UK charity “Local Trust” (https://localtrust.org.uk/) commonly uses the experience of different built environments to stimulate deliberation. Rather than getting an urban designer to say “but what about density and air pollution” they take a community to see a high street with lots of well-designed spaces that is used by “people like them”. All of these instances can be broadly understood as forms of deliberation.

Shelter’s Living Home StandardFootnote6 (2016) is perhaps the most ambitious attempt to develop a framework for evaluating housing outcomes through bottom-up deliberative democracy. Drawing heavily on the philosophy of JRF’s minimum income standard (Bramley and Bailey Citation2018), the Standard was “the first definition of what home means that has been defined by the public, for the public”. The process was democratic, starting from the bottom-up and asking residents what they value about home and neighbourhood, and also deliberative: the idea wasn’t to produce a long wishlist of housing attributes, incorporating and aggregating everyone’s preferences, but to draw people towards a common view about what an acceptable home would look like. Findings from other citizen juries suggest that participants are open-minded, willing to engage and change their mind, and prepared to take the process seriously, providing recommendations that can be realistically implementedFootnote7, and this was true of the final Living Home Standard which was ambitious without being unrealistic (according to a survey, 58% of homes in the UK met it).

Although it starts from the bottom-up, a deliberative democracy does not preclude a role for experts. “In a deliberative democracy, learning how to think for oneself, to question, to criticize, is fundamental” but as Putnam (Citation2001, 25) notes, “thinking for oneself does not exclude – indeed it requires – learning when and where to seek expert knowledge”. We all have informational blind spots. Despite looking fine, new-build housing may in fact be environmentally unsustainable, of poor quality or structurally unsound. An area that feels dangerous to local people may, according to the data, be relatively crime-free. By providing citizens with evidence and making them more aware of the effect that housing (policy) has on the effective freedoms and feelings that they value, experts can improve the informational base upon which capabilities are decided. Juries are perfectly capable of grappling with complex research, given time, patience, and empathetic expert witnesses (Breckon, Hopkins, and Rickey Citation2019)

That said, even if we develop a set of capabilities from the bottom-up and involve the perspectives of critics and experts, there still is no “metaphysical rule” saying that the resulting evaluating framework will be reasonable. Power distorts all reasoning processes, and any democratic approach, including deliberative ones, remains susceptible to a “tyranny of the majority” hijacking the process to advance their own interests. For this reason, the state should reserve the right to intervene on behalf of minorities if they have been unreasonably excluded or subjugated. Indeed, it is notable that although Sen refuses to endorse Nussbaum’s list of 10 capabilities (for reasons stated in Sen Citation2004), he has implicitly argued that being healthy, well-nourished and educated are universal basic capabilities that no person can be reasonably denied (Anand and Sen Citation2000, 85).

Conclusion

In this paper, I have argued that the examination and evaluation of housing outcomes require us to make value-based, as well as factual, judgements. Unfortunately, most of the social scientific literature to date has responded to this entanglement of fact and value by side-lining normative reasoning, with both neoclassical economists and social constructionists arguing that value-based judgements are subjective and therefore beyond the realm of reason. The divorce between positive and normative has been damaging for both sides. On the one side, it has severely stunted social scientists’ understanding of normative thought, and arguably eroded our ability to engage in normative reasoning. On the other side, it has led philosophy to become overly abstracted from concrete social practice (Olson and Sayer Citation2009). As both sides grow further apart, engagement with each other becomes harder to countenance.

I have drawn on the work of Sen and Putnam to argue that although all value judgements are position-dependent, some are more reasonable than others and the best way of discriminating between them is generally through a bottom-up process of deliberative democratic reasoning which focusses on maximizing people’s housing capabilities: the effective freedoms that people have in their homes and neighbourhoods to do and feel the things they have reason to value.

While arguing that housing capabilities represented the best “information space” for evaluating housing outcomes, I also recognized that, in practice, it is difficult to operationalize. Therefore, it is reasonable that evaluators use subjective, objective and economic indicators as proxies for housing capabilities. If the vast majority of people value more living space, then it would seem reasonable to use objective metrics of overcrowding as metric of progress, provided we remember that it is the underlying capability to have an adequate level of living space that is important. Likewise, if the vast majority of people value being happy, then we could use subjective well-being indicators (such as life satisfaction) as metrics of progress, provided we remember that people have good reason to value freedoms that are detrimental to their happiness.

Shelter’s Living Home Standard is the closest thing that I know to a set a of housing capabilities developed through deliberative democracy, and it would useful if this were incorporated into the English Housing Survey (and UK equivalents), so that evaluators can track the attributes of home that citizens actually value. This would then allow researchers and policymakers to ground different housing concepts and standards such as housing-inequality, affordability, overcrowding and the Decent Homes Standard in the deliberative reasoning of citizens.

Future research could also explore the extent to which the effective freedoms people value from home vary by location, nationality, age, gender, ethnicity, class; and examine how bottom-up deliberative democratic forums, and “democratic innovations” (Elstub and Escobar Citation2017) can reconcile conflicting values and enable society to muddle through local problems such as disagreement between residents and housing association practitioners over regeneration projects or social housing allocations policies, and national problems such as land-value capture. In all the above, it is essential that we understand the role that power has to play in shaping values, discourses and negotiation – and the ways which power imbalances can be addressed so that the better reason may prevail.

The argument summarized above also has some broader implications for housing studies as a discipline. For one thing, the entanglement of fact and value implies that we should be more relaxed about using those “thick ethical concepts” like “impoverished” or “humiliating” (Williams Citation1985) which contain a value, as well as factual, component. If “description” involves choosing from a set of possibly true statements on the grounds of their relevance (as Sen Citation1980 posited), then one of these grounds may reasonably relate to ethical concerns. For another, it implies that the role of (housing) philosophy is not to discover an eternal and universal theory of justice, but to test the moral intuition of citizens and probe for logical inconsistencies or, as Isiah Berlin (Citation1978, 11) put it “to assist men to understand themselves and thus operate in the open, and not wildly, in the dark”

Acknowledgements

In its slow evolution, this has benefited considerably from the input of a whole range of academics and non-academics. In particular, I‘d like to thank: the referees whose suggestions throughout have been tremendously useful; those who attended the CaCHE seminar on this topic in London in Spring 2019 and provided such insightful comments; and David Clapham for all the stimulating conversations on this topic.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. As Peter Housden, then Permanent Secretary of CLG put it, “on its two key indicators – vacancy rates and the relation to regional house prices – the pathfinder areas are demonstrably succeeding in their objectives”. House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts, 2008, Housing Market Renewal: Pathways. Available online at; https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200708/cmselect/cmpubacc/106/106.pdf.

2. For example, ideas of moral equality are present in the Jerusalem-based religions which span much of the world’s population (Putnam Citation1987: 60–61).

3. www.sectorscorecard.com.

4. 2008 is the most recent year that respondents were asked this question.

5. In this section, we use the word “objective” in its epistemologically naïve sense, as a metric of housing outcomes that is defined according to some uniform, commonly agreed standard.

6. For more details see, http://www.shelter.org.uk/livinghomestandard.

7. See, for example, the findings from a citizen assembly on Social Care undertaken in June 2018 (https://www.involve.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/).

References

- Allen, C. 2008. Housing Market Renewal and Social Class. London: Routledge.

- Anand, S., and A. Sen. 2000. “The Income Component of the Human Development Index.” Journal of Human Development 1 (1): 83–106. doi:10.1080/14649880050008782.

- Anderson, E. 2003. “Sen, Ethics, and Democracy.” Feminist Economics 9: (2–3. doi:10.1080/1354570022000077953.

- Bellet, C. 2017. “The Paradox of the Joneses: Superstar Houses and Mortgage Frenzy in Suburban America.” CEP Discussion Paper, 1462.

- Bengtsson, B. 1995. “Politics and Housing markets – Four Normative Arguments.” Scandinavian Housing and Planning Research 12 (3): 123–140. doi:10.1080/02815739508730382.

- Benhabib, S. 1986. Critique, Norm, and Utopia: A Study of the Foundations of Critical Theory. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Berlin, I. 1978. Concepts and Categories: Philosophical Essays. Henry Hardy (ed.). London: Hogarth Press. New York, 1979: Viking; 2nd ed., Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013.

- Bohman, J. (Ed.), 1997. Deliberative Democracy: Essays on Reason and Politics. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Bramley, G., and N. Bailey 2018. Poverty and social exclusion in the UK: Vol. 2: Volume 2 - The dimensions of disadvantage.

- Breckon, J., A. Hopkins, and B. Rickey 2019. Evidence vs Democracy

- Cheshire, P. 2018. “Housing: The Happy Self-delusion of ‘No Shortage’.” http://spatial-economics.blogspot.com/2018/03/

- Clapham, D. 1997. “The Social Construction of Housing Management Research.” Urban Studies 34 (5–6): 761–774. doi:10.1080/0042098975817.

- Clapham, D. 2018. Remaking Housing Policy.

- Clapham, D., C. Foye, and J. Christian. 2018. “The Concept of Subjective Well-being in Housing Research.” Housing, Theory and Society 35 (3): 261–280. doi:10.1080/14036096.2017.1348391.

- Clark, A. E., P. Frijters, and M. A. Shields. 2008. “Relative Income, Happiness, and Utility: An Explanation for the Easterlin Paradox and Other Puzzles.” Journal of Economic Literature 46 (1): 95–144. doi:10.1257/jel.46.1.95.

- Coates, D., P. Anand, and M. Norris. 2013. “Housing and Quality of Life for Migrant Communities in Western Europe: A Capabilities Approach.” Journal on Migration and Human Security 1: 163. doi:10.1177/233150241300100403.

- Cohen, G. A. 1993. Equality of What? on Welfare, Goods, and Capabilities. The Quality of Life. M. C. N. A. A.Sen. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cole, I., and J. Flint. 2007. Demolition, Relocation and Affordable Rehousing: Lessons from the Housing Market Renewal Pathfinders. London: Joseph Rowntree Foundation by the Chartered Institute of Housing.

- Crocker, D. A. 2006. “Sen and Deliberative Democracy.” Capabilities Equality 155 (197): 155–197. ROUTLEDGE in association with GSE Research.

- Elstub, S., and O. Escobar 2017. “A Typology of Democratic Innovations.” In Political Studies Association’s Annual Conference. Glasgow

- Fitzpatrick, S., and B. Watts. 2017. “Competing Visions: Security of Tenure and the Welfarisation of English Social Housing.” Housing Studies 32 (8): 1021–1038. doi:10.1080/02673037.2017.1291916.

- Fitzpatrick, S., and B. Watts. 2018. “Taking Values Seriously in Housing Studies.” Housing, Theory and Society 35 (2): 223–227. doi:10.1080/14036096.2017.1366941.

- Flyvberg, B. 1998. Rationality and power: Democracy in action.

- Friedman, M. 1953. The methodology of positive economics.

- Gurney, C. M. 1999. “Pride and Prejudice: Discourses of Normalisation in Public and Private Accounts of Home Ownership.” Housing Studies 14 (2): 163–183. doi:10.1080/02673039982902.

- Haffner, M., and M. Elsinga. 2019. “Housing Deprivation Unravelled: Application of the Capability Approach.” European Journal of Homelessness 13 (1): 13.

- Jacobs, K., and T. Manzi. 2000. “Evaluating the Social Constructionist Paradigm in Housing Research.” Housing, Theory and Society 17 (1): 35–42. doi:10.1080/140360900750044764.

- Kemeny, J. 1984. “The Social Construction of Housing Facts.” Scandinavian Housing and Planning Research 1 (3): 149–164. doi:10.1080/02815738408730045.

- King, P. 2017. Thinking on Housing: Words, Memories, Use. London: Routledge.

- Leather, P., and I. Cole. 2009. National Evaluation of Housing Market Renewal Pathfinders 2005-2007. London: Department for Communities and Local Government.

- Meen, G. 2018. How should housing affordability be measured?

- Nagel, T. 1986. The View From Nowhere. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Nakazato, N., U. Schimmack, and S. Oishi. 2011. “Effect of Changes in Living Conditions on Well-being: A Prospective Top–Down Bottom–Up Model.” Social Indicators Research 100 (1): 115–135. doi:10.1007/s11205-010-9607-6.

- Nussbaum, M., and A. Sen. 1987. Internal criticism and Indian rationalist traditions.

- Nussbaum, M., and A. Sen, Eds.. 1993. The Quality of Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Nussbaum, M. C. 2011. Creating Capabilities. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Olson, E., and A. Sayer. 2009. “Radical Geography and Its Critical Standpoints: Embracing the Normative.” Antipode 41 (1): 180–198. doi:10.1111/anti.2009.41.issue-1.

- Pader, E. 2002. “Housing Occupancy Standards: Inscribing Ethnicity and Family Relations on the Land.” Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 300–318.

- Pader, E. J. 1993. “Spatiality and Social Change: Domestic Space Use in Mexico and the United States.” American Ethnologist 20 (1): 114–137. doi:10.1525/ae.1993.20.1.02a00060.

- Pader, E. J. 1994. “Spatial Relations and Housing Policy: Regulations that Discriminate against Mexican-origin Households.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 13 (2): 119–135. doi:10.1177/0739456X9401300204.

- Provan, B., A. Belotti, and A. Power. 2016. “Moving on without moving Out: The Impacts of Regeneration on the Rayners Lane Estate.” http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/67851/1/casereport100.pdf

- Putnam, H. 1987. The many faces of realism.

- Putnam, H. 1990. Realism with a Human Face. (Ed.) J. Conant. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Putnam, H. 1992. Renewing Philosophy. Harvard University Press.

- Putnam, H. 1994. Words and Life. (Ed.) J. Conant. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Putnam, H. [1992] 1995. Pragmatism: An Open Question. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Putnam, H. 2001. Enlightenment and Pragmatism. Assen: Uitgeverij Van Gorcum.

- Putnam, H. 2002. The Collapse of the Fact/value Dichotomy and Other Essays. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Putnam, H. 2003. “For Ethics and Economics without the Dichotomies.” Review of Political Economy 15 (3): 395–412. doi:10.1080/09538250308432.

- Putnam, H. 2017. Pragmatism as a Way of Life: The Lasting Legacy of William James and John Dewey. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Putnam, H. W. 2008. “Capabilities and Two Ethical Theories.” Journal of Human Development 9 (3): 377–388. doi:10.1080/14649880802236581.

- Read, D. 2007. “Experienced Utility: Utility Theory from Jeremy Bentham to Daniel Kahneman.” Thinking & Reasoning 13 (1): 45–61. doi:10.1080/13546780600872627.

- Reiss, J. 2017. “Fact-value Entanglement in Positive Economics.” Journal of Economic Methodology 24 (2): 134–149. doi:10.1080/1350178X.2017.1309749.

- Rice, C. M. 2013. “Defending the Objective List Theory of Well‐Being.” Ratio 26 (2): 196–211. doi:10.1111/rati.2013.26.issue-2.

- Robeyns, I. 2006. “The Capability Approach in Practice.” Journal of Political Philosophy 14 (3): 351–376. Cambridge. doi:10.1111/jopp.2006.14.issue-3.

- Sen, A. 1979. “Utilitarianism and Welfarism.” The Journal of Philosophy 76 (9): 463–489. doi:10.2307/2025934.

- Sen, A. 1980. “Description as Choice.” Oxford Economic Papers 32 (3): 353–369. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.oep.a041484.

- Sen, A. 1985. “Well-being, Agency and Freedom: The Dewey Lectures 1984.” The Journal of Philosophy 82 (4): 169–221.

- Sen, A. 1992. Inequality Reexamined. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sen, A. 1993. “Positional Objectivity.” Philosophy & Public Affairs 22 (2): 126–145. Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/2265443

- Sen, A. 2004. “Capabilities, Lists, and Public Reason: Continuing the Conversation.” Feminist Economics 10 (3): 77–80. doi:10.1080/1354570042000315163.

- Sen, A. 2005. “Walsh on Sen after Putnam.” Review of Political Economy 17 (1): 107–113. doi:10.1080/0953825042000313834.

- Sen, A. K. 1980. “Equality of What?” In Tanner Lectures on Human Values Vol. 1, edited by S. McMurrin. England: Cambridge University Press.

- Sen, A. K. 2009. The Idea of Justice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Tanekenov, A., S. Fitzpatrick, and S. Johnsen. 2018. “Empowerment, Capabilities and Homelessness: The Limitations of Employment-focused Social Enterprises in Addressing Complex Needs.” Housing, Theory and Society 35 (1): 137–155.

- Treasury, H. M. S. 2018. The Green Book: Central Government Guidance on Appraisal and Evaluation. London: HM Treasury. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/685903/The_Green_Book.pdf

- Varoufakis, Y. 2002–2003. “Against Equality.” Science & Society 66 (4): 448–472. doi:10.1521/siso.66.4.448.21109.

- Walsh, V. 2003. “Sen after Putnam.” Review of Political Economy 15 (3): 315–394. doi:10.1080/09538250308434.

- Wilkes, V., and D. Mullins 2012. “Community Investment by Social Housing Organisations: Measuring the Impact.” Third Sector Research Centre Survey Report for HACT.

- Williams, B. 1985. Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy. London: Fontana Press/Collins.

- Wilson, W. 2013. Housing Market Renewal Pathfinders. London: House of Commons Library.