ABSTRACT

This article critiques Kemeny’s theory of housing regimes to explain housing systems change. Power balances mediated through institutional structures are underlying causes of housing regimes in Kemeny’s schema in which the design of cost-rental sectors defines whole housing systems. However, the distinctive “unitary” systems Kemeny identified in Germany and Sweden are breaking down as economic failure prompted reforms to wider welfare systems, whilst mature cost-rental sectors were unable to maintain supply without subsidies. These mis-specifications in the theory have been exacerbated by the rise in unorthodox monetary policy. As poverty rates have risen, so the boundaries of possibility have shrunk, rendering “housing for all” approaches problematic and heralding more acute policy trade-offs. Nonetheless, policy choice and institutional differences counterbalance forces of convergence. Understanding system change requires theories of the middle range to be extended upwards to capture high-level forces of convergence and downwards to capture institutional detail that explains the difference.

1. Introduction

Understanding how housing systems function and change is one of the most enduring challenges in housing studies. Monochrome microeconomic approaches (e.g. World Bank Citation1993) which adopt market efficiency as the sole benchmark against which systems should be judged lack explanatory power and are intolerant of difference. Within housing studies, an alternative approach has been developed. Always inspired by and often derived from Esping-Andersen’s (Citation1990) Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism the housing-welfare regime approach has provided for a deeper analysis in which distinctive housing systems can emerge in parallel to wider welfare systems, with (contested) relationships between the two.

Of the practitioners of the housing-welfare regime framework, “the most influential is assuredly Jim Kemeny” (Blackwell and Kohl Citation2018, p. 1447). His theory of housing regimes centred around and developed from his (Citation1995) book, From Public Housing to the Social Market, audaciously suggests that the organization of cost-rental housing can shape the nature of the rental sector as a whole, and in turn, create a whole housing system. It is frequently used as the basis of country selection in comparative studies, and sometimes adopted as the independent variable in establishing housing outcomes (e.g. Borg Citation2014). It is the completeness and influence of Kemeny’s theory that makes it a suitable lens through which to analyse housing system change.

This article offers a critique of Kemeny’s theory of housing regimes as a means of explaining how housing systems are changing. It begins by locating Kemeny’s theory within the housing studies literature. A critical synthesis of Kemeny’s theory drawn from his relevant works is then presented. The theory is assessed through structured case studies of three housing systems (Germany, Sweden and the UK), which feed into a discussion that addresses the key issue. Implications of the findings for theory are suggested in the concluding section.

2. Locating Kemeny’s Theory in the Literature

Through his work on housing regimes, Kemeny sought to develop theory in housing studies which he believed had too often presented descriptions of policies and institutions that were uninformed by theory and consequently lacked explanatory power (Atkinson and Jacobs Citation2016). He is particularly critical of the approach “which juxtapose[s] the housing systems of a number of countries but which eschew[s] any attempt at generalising.” (Kemeny and Lowe Citation1998, p. 161)

Equally, he rejects convergence theories whereby “all modern societies are developing in a particular direction …” (Kemeny and Lowe Citation1998 p. 161). He therefore also rejects “universalistic” approaches that emphasize economic structure (“structural determinism”, Kemeny Citation1995 p. 38) as providing the explanation for the development of housing systems. He identifies Marxist approaches, including Harloe (Citation1995), as examples of this tradition, but it might equally apply to the most recent studies that identify neo-liberalism as driving convergence in housing systems so they become more marketized, commodified and individualized (Clapham Citation2019).

In contrast, Kemeny adopts the sociological theory of a middle range which provides “a more qualitative, culturally sensitive and historically grounded approach [than the alternatives]” (Kemeny and Lowe Citation1998, p. 162). This approach allows for typologies of housing systems to be “derived from cultural, ideological, political dominance or other theories as the basis for understanding the differences between groups of societies” (Kemeny and Lowe Citation1998, pp. 161–162). Consequently, he embraces “policy constructivism” which stresses “the importance of long-term policy in interaction with economic processes within rental housing stocks for the structuring of tenures.” (Kemeny Citation1995, p. 39).

Kemeny’s approach is part of a broader tradition associated with Esping-Andersen whose work on welfare regimes also sought to counter the “under-theorisation of the welfare state” (Citation1990, p. 107). There are differences, notably Kemeny’s rejection of working-class mobilization theory and his placing of greater emphasis on ideological preferences. Esping-Andersen’s framework of liberal, conservative and social-democratic regimes has, of course, been “read across” (Stephens Citation2016) or translocated (Aalbers Citation2016), to housing studies. This practice “has some logic if regime theory reflects causes … if power configurations in a country favour a social-democratic welfare regime, then we might expect the same configurations to apply to housing” (Stephens Citation2016, p. 23), but equally there are good reasons to be cautious of such a “self-evident categorisation” (Aalbers 2016, p. 9) due to variations in housing systems within the same welfare regime, and (pace Torgersen Citation1987) the distinctive nature of housing compared to the principal three pillars of the welfare state (namely education, health and social security). Aalbers (2016) warns that generalization in such circumstances may render the use of Esping-Andersen’s regimes “irrelevant and useless” whilst Kemeny himself warned against “mindless classification” (Citation2001, p. 61).

Nonetheless, Kemeny’s theory is part of a body of work which is now recognized as “housing-welfare regime approaches” (Blackwell and Kohl Citation2018, after Stephens Citation2016), in which there is a dynamic relationship between the housing and broader welfare regime. Aalbers criticizes prioritizing “the analysis of housing as a public policy of the welfare state rather than as a public policy in its own right … [which] is to reduce the study of housing to only one side of housing …” (Citation2016, p. 10). However, the “welfare state” is rather narrower than the “welfare regime” which also captures those broader economic institutions surrounding the labour market.

The body of work Aalbers (2016) has developed around financialization represents a form of “soft” convergence in which an exogenous global force, or “general mechanism” from outside the housing system (the “global wall of money”, p. 139), is mediated through distinctive institutional structures which he calls “specific conditions … at work in different housing markets …” (ibid.). Nonetheless, he notes “the remarkable congruence of actually-existing housing situations around the world …” (ibid.).

Considerable though the contribution of Aalbers’ work on financialisation is, it does not represent a complete theory of housing system change. By bringing the financialisation thesis back within regime approaches, Schwartz and Seabrooke (Citation2008) made a considerable effort to develop theory. Although their varieties of residential capitalism (VORC) badge are derived from the regime approach associated with the industrial organization, they explicitly adopt elements of welfare-regime theory. They argue that home-ownership levels reflect different state-market-family arrangements associated with welfare regimes, but households’ relationships with global financial markets are shaped by the availability of mortgage debt. Combinations of these variables determine the nature of a residential capitalist regime, for example, a country with high home-ownership and low debt as being “familial” and one with low ownership and low debt as being “state developmentalist”. Empirically, the framework is “substantially defective” (see Stephens Citation2016, p. 1212), but it nonetheless alerts us to the importance of the broader system of social and economic organization.

Blackwell and Kohl (Citation2018) argue that more attention should be paid to elements of the housing system that pre-existed the development of welfare states in the twentieth century. They argue that, for example, current patterns of home-ownership and mortgage debt have been influenced by the distinct housing finance systems and form of the built environment that they created in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries before welfare states had fully emerged. They, therefore, concur with Aalbers’ argument that it can be misleading to privilege the relationship between housing and the welfare state, although the emphasis on path dependency is one that Aalbers had previously dismissed as “not an explanation”, rather “an accepted way of saying that ‘history matters’” (2016, p. 8).

A banal but pertinent possibility is that Kemeny’s theory is merely outdated. Observing that Kemeny’s core text reflects housing systems as they were in the early to mid-1990s, Stephens (Citation2016) suggests that “it is important to ask whether they are still relevant” (Citation2016, p. 25). Blackwell and Kohl (Citation2018) further suggest that precisely the same critique applies to the Schwartz and Seabrooke (Citation2008) VORC approach noting that it reflects “a snapshot of the much more volatile debt measures in the late 1990s” (ibid., p. 306).

3. Kemeny’s Theory of Housing Regimes: A Critical Synthesis

Understanding the whole of Kemeny’s typology of housing regimes requires reference to a series of publications, published over a period of about a decade. Although Kemeny’s (Citation1995) book is most commonly referenced in relation to it, the typology was further developed in a number of articles published in the years up to 2006. The typology was extended by Kemeny, Kersloot, and Thalmann (Citation2005) to differentiate between unitary and integrated rental markets, and the notion of housing (as opposed to rental) regimes was introduced in Kemeny (Citation2006). Meanwhile, the underlying theoretical and empirical relationship between housing and wider welfare regimes was discussed in Kemeny (Citation2001) and developed in Kemeny (Citation2005) and Kemeny (Citation2006). The present critical synthesis of his theory is derived from these works and covers the causes of housing regimes, the construction of rental markets, the dualist and unitary rental strategies, and the wider welfare regime.

3.1 Causes of Housing Regimes

Kemeny identifies three causes of housing and wider welfare regimes: the balance of power between capital and labour, its mediation through what can be thought of as an underlying societal ideology, and accompanying social, economic and political institutions.

In addressing the balance of power between capital and labour, Kemeny is wary of “labour movement theory” (equivalent to Esping-Andersen’s (Citation1990) “working class mobilisation theory”) which suggests that the welfare state is “the outcome of the relative strength of the labour movement and its political ability to implement collective welfare provision through electoral control of the state” (Citation1995, p. 64). However, although he prefers the “theory” of corporatism, he sees these two approaches as being compatible, at least to the extent that there is no “irreconcilable contradiction” (Kemeny Citation1995, p. 65) between them.

“Corporatist” countries are informed by an underlying ideology of “ordo-liberalism” which provides an alternative to the “profound statism” preferred by labour politicians in Anglophone countries. The theory was developed by the Ordo-Kreis (“order group”) as a third way between free-market capitalism and communism in 1930s in Germany. It gives rise to a “social market economy” (a term better known than “ordo-liberal” outside Germany) which “attempts to construct markets in such a way as to strike a balance between economic and social priorities and thereby ameliorate the undesirable effects of the market from within” (Citation1995, p. 11). Kemeny charts the well-documented roles of Ludwig Erhard as Minister of Economic Affairs and Chancellor (providing economic leadership), and Muller-Armack as under-secretary of state in the late 1950s and early 1960s who “became the political mediator for the implementation of ordo-liberalism during the early critical years of German’s reconstruction …. [when] the foundations were laid for the post-war German economic and social order” (Citation1995, p. 14). He claims (without documentary support) that the concept spread to neighbouring small countries such as the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden and Austria.

In Kemeny’s schema, the relative strength of labour is mediated through the formal corporatist structures, i.e. a “system of co-operation and compromise between capital and labour that is orchestrated by the state” (Citation1995, p. 65). He draws particular attention to adversarial legal systems and (two-party) electoral systems in Anglophone societies, in contrast to inquisitorial legal systems and multi-party electoral politics that typically deliver coalition governments in most of Europe and Scandinavia. He implies that the separation of the political and work-place wings of labour movements in Anglophone societies leads to their political wing seeking solutions to social problems through state institutions, so giving rise to a “profound statism” (Citation1995, p. 67). Differences in the balance of power between different interest groups located in the different “sectors” of the welfare state mean that “large differences can arise between welfare sectors in the power balance between diverse interests” (Kemeny Citation2006, p. 9). The result is a series of “sector regimes”.

The relationship between housing and broader welfare regimes is developed in Kemeny (Citation2001) and Kemeny (Citation2006). Kemeny (Citation2001) argues that housing represents a fourth pillar of the welfare state. Indeed, after Esping-Andersen’s identification of distinct “pension regimes” and “labour market regimes”, he suggests that housing is one of the several “sector regimes”. He provides an interpretation of Esping-Andersen in which

… different regimes derive from different power structures and constellations of class-derived power relationships. The three regimes are social democratic, corporatist and liberal. These, in turn, generate welfare systems that can be called decommodified, conservative and residual, respectively. (Citation2001, pp. 58-59)

In this distinction between regime and system, the regime is the independent variable and the system is the dependent variable. He further argues that Esping-Andersen’s “social democratic” regime is, in fact, part of the family of corporatist welfare regimes.

3.2 The Construction of Rental Markets

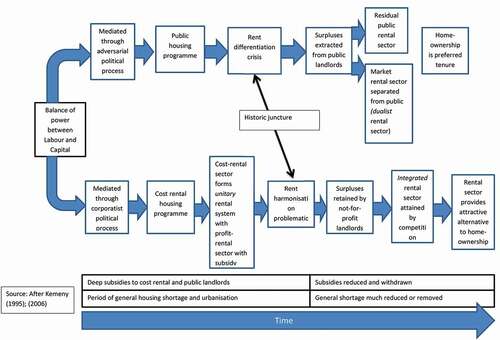

Kemeny’s typology of rental markets is illustrated in , which illustrates how two kinds of rental (and later, housing) systems emerge. The typology is grounded in the “fairly unique” (Kemeny Citation1995, p. 163) circumstance of the postwar period when many countries faced acute housing shortages, and sometimes experienced additional housing pressures from urbanization. These circumstances lead to the adoption of some form of the government-subsidized housing programme. However, the size and nature of that programme depend on the balance of power between capital and labour, and whether this was mediated through adversarial Anglophone or Germanic corporatist political structures. Over time, these respond in different ways to the “maturation” of the public/cost rental sector, which tends towards surplus as the housing shortage declines and housing debts are repaid.

3.2.1 The Dualist Rental Strategy

In Anglo-American “dualist” systems, the profit-driven market creates acute social problems that result in demands for a public sector safety net, the size of which depends on the balance of power between competing interests. In any case, it is kept separate from the market in order to shelter the market sector from the cost sector, so creating a “curious dualism” (Kemeny Citation1995, p. 9) between them. Nonetheless, as the state sector matures its rents fall relative to market rents, which results in a “rent differentiation crisis”. Presented with this historic juncture, the government will tighten control over the cost-rental sector, force rents to rise, preventing (re)investment and reversing the maturation process by allowing tenants to purchase properties at discount. The result is that the cost-rental sector becomes residualised as access is restricted to the poor and supply is limited. He characterizes its management as being akin to a socialist “command” economy as the government leaves public/social landlords with little discretion, and rents are insensitive to market conditions. Hence, “[t]he public housing sector has all the signs associated with planned economy in communist countries … creating a poor law sector”Footnote1 (Kemeny Citation2006, p. 3). Housing allowances may be necessitated by high rents in the public sector, which may be paid for by other public sector tenants who are not claimants. With access to public housing restricted, and the for-profit rental sector being unattractive due to high rents and lack of security, demand shifts towards owner-occupation that has to be subsidized in order to support marginal owners. The high level of representation of low-income home-owners in these systems, he claims, contributes towards housing market instability.

He identifies “Britain” (particularly England), Ireland, USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand as examples of the dualist model, to which he adds Finland and Iceland from the Nordic bloc (even though the Nordic countries are not examined in any detail). He later rather casually adds “most Mediterranean countries” to this group (Kemeny Citation2001).

3.2.2 The Unitary Rental Strategy

In the Germanic unitary systems, a different strategy is adopted. In the early years of a subsidized housing programme, an “integrated” or “unitary” rental market is achieved through a mixture of subsidies provided to cost-rental landlords, and the regulation of rents in the for-profit rental sector. In his 1995 book, Kemeny uses the terms “integrated” and “unitary” synonymously. However, in an article he describes as being “a first attempt to go beyond the typology outlined in Kemeny (Citation1995)” (Kemeny, Kersloot, and Thalmann Citation2005, p. 856), he distinguishes between the two.

In the early phase of a subsidized housing programme, the cost or non-profit sector requires subsidy and the profit sector to be regulated, in order for the former to be able to compete with the latter so creating a unitary rental market. As the cost-rental sector matures a “harmonisation problematic” (parallel to the “rent differentiation” crisis in dualist systems) emerges when the cost-rental sector is able to exert sufficient downward pressure on private rents and the government needs to decide when to abolish rent control. At this point it becomes an “integrated” rental market, although some important “state interventions may remain” (Kemeny, Kersloot, and Thalmann Citation2005, p. 859). For example, second-generation rent regulation might replace first-generation rent control. The conditions that are required for such competition are, in addition to competitive rents, a high degree of security of tenure and sufficient “market coverage” (ibid.). The nature of an integrated or unitary rental market differs from dualist rental markets in important ways. An integrated market might well be characterized by economists as being a “social market” with “demand sensitive” rents pooled across the stock of non-profit housing, rather than the historic costs of individual buildings or estates. It is also implied that non-profit housing will be open to a wide range of households.

A crucial consequence of a unitary (or integrated) rental market is that it “will be highly competitive with owner occupation and will retain a large proportion of households, including better off households” (Kemeny Citation1995, pp. 38–39). It is the knock-on effects of the different kinds of rental systems on home-ownership that imply that the theory is one that seeks to explain the nature of the entire housing system, and not merely the rental sectors.

Kemeny (Citation1995) identifies Sweden, the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, Austria and Denmark as countries that are “moving towards” unitary rental markets. Kemeny introduced some distinctions in a later paper in which non-profit rental sectors can “influence, lead and dominate the market” (Citation2005, p. 855), using the examples of Switzerland (“weakly-influencing”), Sweden (“strongly influencing”) and the Netherlands (“dominating”) as illustrations.

3.3 The Wider Welfare Regime

The degree of influence by the non-profit sector over the rental market is linked to the wider welfare regime in a paper published in 2006, but which confusingly does not adopt the distinction between integrated and unitary markets developed in the paper published in the previous year.Footnote2 Kemeny maintains that Esping-Anderen’s social-democratic welfare-regime type is “a variant of corporatism” (Citation2006, p. 15). In Esping-Andersen’s view, corporatist regimes are merely the product of stalemate in the conflict between capital and labour, but Kemeny notes that scholars of corporatism rank both the Nordic and Germanic countries as being corporatist (Kemeny Citation2006).

The distinction between corporatist countries which are “labour-led” and those which are “capital led” may help to explain the different emphases on state and market providers of cost-rental housing within the unitary regimes, and the relative size of the non-profit sector (see ). The balance between labour and capital may vary between sectors of the welfare regime, so labour may be stronger through unions in the labour market, or tenants in the housing market and pensioners’ associations. Hence,

To what extent different sectors are labour-led can vary, regardless of the extent to which the welfare system as a whole is labour-led. (Kemeny Citation2006, p. 9)

Table 1. Esping-Andersen’s regime types, compared to a left-right scale of regime types, and housing regimes

Table 2. Employment rates (%)

Table 3. Poverty (% individuals) in 2017

Table 4. Tenure of individuals living in poverty

However, Kemeny’s suggestion that housing represents a fourth pillar developed in parallel with wider welfare regime takes us only so far and leaves underdeveloped his thinking regarding a dynamic relationship between the wider welfare and housing regimes. His earlier (Kemeny Citation1981) work suggested an inverse relationship between levels of home-ownership and the strength of the welfare state. He suggests that this arises from the front-end-loaded nature of mortgage debt leading to home-owning voters to prefer low taxation over social expenditure. Subsequently, the attainment of outright ownership in retirement compensates for frugal state pensions. This thesis later became known as the “really big trade off” (after Castles Citation1998), but was supplemented by further another hypothesis:

… if those countries that still today enjoy a functioning integrated rental market and have low rates of home ownership begin to experience major declines in welfare – especially among the elderly – we can expect them to begin to transform into monotenural home owning societies. (Kemeny Citation2005, p. 59)

Here, housing system change is being driven by welfare system change, a theme to which we shall return.

4. The Theory Examined

In this section, we present a structured re-examination of three countries selected because they that were previously analysed by Kemeny: Germany and Sweden as unitary housing markets, and the UK as a dualist market. Given the need to consider the relationship between housing and the wider welfare system this selection was also influenced by a wish to include countries that fall into the categories of corporatist (Germany), social democratic (Sweden) and liberal (UK) welfare regimes within Esping-Andersen’s schema. The three countries are examined in turn, starting with a consideration of the political and economic context, and the way in which the wider welfare regime has changed, followed by overviews of the housing system in the mid-1990s (when Kemeny’s core text was published) and then an assessment of how it has changed since then.

4.1 Germany

4.1.1 Context

According to Kemeny (Citation1995), Germany is the home of the ordo-liberal philosophy that gave rise to social market institutions, including unitary housing markets. Ordo-liberalism may be distinguished from neo-liberalism. The latter “is naturally against all forms of state interference in markets. Its attitude is essentially laissez faire … In contrast ordo-liberalism sees a vital role for the state in ensuring that markets stay close to some notion of an ideal market” (Wren-Lewis Citation2014).

Ordo-liberalism was particularly strong within the Christian and Free Democrat parties. Together with the Christian Social Union these parties dominated the Governments of the Federal Republic of Germany from its formation until the mid-1960s and so oversaw the establishment of the key institutions. This included Germany’s macroeconomic policy which was based on the pursuit of low inflation attained through an independent central bank (Guerot and Dullien Citation2012). The commitment to ordo-liberalism also helps to explain the design of the Euro, which like the Deutschmark is based on the over-riding importance of low inflation and a rejection of Keynesian counter-cyclical fiscal policy.

The German social security system was founded on the Bismarckian principle of social insurance and supported a “male breadwinner” labour market model. Both came under pressure in the 1990s, when some cuts to social security were made as a result of the extreme budgetary pressures of unification rather than ideology (Clasen Citation1997). However, the poor performance of the German labour market in the 1990s led the Social Democrat-led government to introduce far-reaching reforms to both social security and the labour market. The “Hartz IV” reforms, in particular, have been characterized as “neoliberal” in character (Guerot and Dullien Citation2012), and follow the logic of the OECD (Citation1994) Jobs Study that advocated labour market flexibility as a means of increasing employment.

The performance of the German economy has improved since the late 1990s, and it escaped the worst effects of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). It has been relieved of the burden of providing the anchor currency in the Exchange Rate Mechanism that preceded the Euro. Both male and (in particular) female employment rates have risen so that Germany no longer resembles a “male breadwinner” model. Indeed, female employment is now higher than in the UK ().

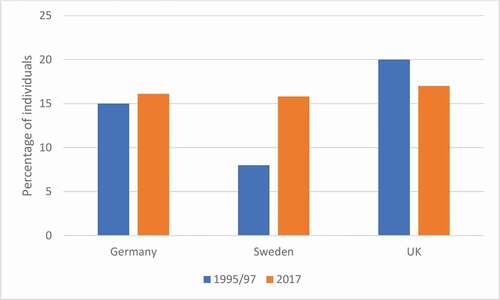

However, there has been an increase in part-time employment including “mini-jobs” and the growth in productivity has arisen from a downward pressure on wages reflected in a lower share of output. According to Lapavitsas et al. (Citation2012), “The euro is a ‘beggar-thy-neighbour’ policy for Germany, on condition that it beggars its own workers first” (quoted by Bieler Citation2013). The general poverty rate is 16.1%, similar to the mid-1990s (), but in-work poverty has almost doubled since 2005 (to 9.1% in 2017: Eurostat Income and Living Conditions indicator ilc_iw01). The introduction of a minimum wage in 2015 reflected the growth in low-paid employment that had previously been avoided by centrally negotiated wage agreements. Meanwhile, German politics has seen the decline in support for the main centre-right and centre-left parties, now forced into a coalition, whilst the anti-immigrant AfD (Alternative für Deutschland) party has emerged as a destabilizing force.

4.1.2 The German Housing System

Germany built up a substantial social rented sector in the decades following the war. Although Christian Democrat governments provided for subsidy for home-ownership, this was stymied at the state level by Social-Democratic administrations (Kohl Citation2018). About one-quarter of all postwar housing was “social” housing by 1970 (Droste and Knorr-Siedow Citation2014). In contrast to many other countries a range of landlords, including for-profit private landlords, was eligible for the subsidy. Subsidy was intended to reduce rents to below full cost levels in order to allow them to compete with the lower end of the private rental stock, although rents on the older stock would be lower. For a lock-in period of on average 30 years, rents would be limited and eligibility restricted to lower-income groups. Thereafter, the housing leaves the social rented sector and can be let or sold on the open market. The subsidy design means that as shortages were removed and the subsidy programme scaled back, the social stock “melted away” with a net loss of perhaps 80,000 units per year over the past two decades (ibid.). It is now probably under 5% of all stock, but as Droste and Knorr-Siedow (Citation2014) note, the de jure social rented housing is bolstered by de facto social housing particularly in the form of former de jure social housing that is nonetheless in the ownership of organizations with a social purpose, such as municipal housing companies.

The non-social private rented sector was subject to rent controls until the early 1960s, from which point they were phased out in different localities as shortages diminished (McCrone and Stephens Citation1995). Nonetheless, in the early 1970s, the sector was subjected to “second generation” rent control, relating rent increases to rents for similar properties in the market and limiting rent rises to 30% over 3 years, as well as providing security of tenure (ibid.). Landlords were compensated by generous tax treatment, including an accelerated depreciation allowance (replaced with a linear version in 2005) and the ability to offset losses from landlord activities against other income (“negative gearing”) (Gibb, Maclennan, and Stephens Citation2013).

In his book, Kemeny argued,

The finesse of the system is that cost rental housing comprises a substantial pool of low-rent housing to dampen rents in general, and that this stock of housing automatically renews itself as older, low debt housing – both ‘private’ and ‘public’ – passes out of subsidy and therefore out of rent regulation while new build, high debt subsidised housing is added to ‘top-up’ this part of the stock. (Citation1995, pp. 121-122)

He characterized the rental market as being “unitary” in nature and as “part-profit”; and later (Citation2006) as a market “influenced” by the non-profit sector.

In our assessment, in the mid-1990s, Germany’s pursuit of a unitary rental strategy had moved the system close to becoming an integrated rental market.Footnote3 Initially, the cost/non-profit rental sector required subsidy to compete with the for-profit non-subsidized sector, but as the sector first grew then matured the subsidies could be reduced. When the cost/non-profit rental sector was heavily indebted, the for-profit non-subsidized rental sector was subjected to rent control which was replaced with demand-sensitive rent regulation as shortages were removed. Consequently, the rental sectors housed a wide range of households, and crucially provided an attractive alternative to home-ownership, to the extent that it was only one of the two European countries where the rental sector was larger than the ownership sector. Kemeny’s theory works at this point because we can attribute the dynamic between the cost and for-profit rental sectors as being the key driver. Although the formal social rented sector was diminishing and Kemeny did concede that the fall in subsidized new-build might lessen the rent-dampening effect, he maintained that this might well be reversed if demand for such housing rose in response to rising rents.

4.1.3 The Changing German Housing System

The picture has clearly changed since the 1990s.

First, the upswing in new subsidized housing has not occurred. The politics of housing in Germany shifted decisively against social rented housing when the “common interest law” applied to social landlords was abolished in the wake of the Neue Heimat scandal (Power Citation1993). Indeed, in 2006, housing was devolved to the regional governments with the intention that federal subsidies would be phased out, so representing “the final stages of relinquishing responsibility for social housing” (Droste and Knorr-Siedow Citation2014, p. 198). However, with growing population and affordability pressures, and supply lagging behind the Federal Government’s 375,000 annual target, the law has been changed to provide €5 billion federal funding over 2018–21, which when combined with funding from the states is expected to provide 100,000 units of social housing (Federal Republic of Germany Citation2019).

Second, whilst many regional governments continue to subsidize new housing, this is increasingly for home-ownership and it is not financed from the recycling of surpluses as Kemeny’s theory anticipated. On the contrary, since the 1990s, there has been an extensive sales programme by public sector employer and municipal housing company landlords. More than 1.5 million units of housing were sold in the period up to 2006 (Elsinga, Stephens, and Knorr-Siedow Citation2014). Notable disposals included Dresden’s entire public housing stock, more than 150,000 units in Berlin, as well as those owned by the post office, state railway and Krupp. Municipalities in the former German Democratic Republic were in any case obliged to sell 15% of their public housing. These privatizations were part of a wider programme of asset sales prompted by public sector deficits, although it appears to have been infused with a neo-liberal rejection of the state in the market, so was attributable to “both political and ideological pressures” (Elsinga, Stephens, and Knorr-Siedow Citation2014, p. 403). The new landlords (including international financial investors) have often segmented the stock by renovating and selling the most attractive properties. Tenants’ Charters have provided only limited protection. The strategy appears to have drawn to a close, as municipalities have been hit by higher housing allowance and social assistance costs as rents have risen, and in Munich, some housing was bought back (ibid.). However, the loss of municipally owned stock to the profit sector is generally permanent. Further, Wijburg and Aalbers (Citation2017) note that the private equity and hedge funds that were the first to purchase municipal housing have now often sold the housing on to listed real estate companies. The authors speculate that their strategies might include sales to tenants, whilst conceding that “it is difficult to estimate in what direction the German housing market is moving” (ibid., p. 15).

Third, acute shortages have re-emerged in some markets leading to provision for the regulation of rents on new contracts. The law, which was rolled out in Berlin in 2015, is intended to link rents on new contracts to the pool of existing rents on similar properties. Rents on new contracts may not exceed this threshold by more than 10%. The regulation broadly falls within social market principles, at least if the shortages that are driving rent rises are met and the measure is temporary. However, continued rising rents and the emergence of real estate companies such as Vonovia and Deutsche Wohnen have sparked protests in Berlin, Cologne and Munich (BBC Citation2019). In 2019, the Berlin state government went further and introduced a 5-year freeze on rents (Reuters Citation2019). In reality, the “freeze” allows for inflation-related increases and exempts properties built after 2013, but is indicative of the increasing reliance on regulation arising from the weakened market power of the cost-rental sector.

Fourth, Germany has now followed the route of other countries in increasing its reliance on demand-side subsidies to secure housing for low-income households. Eligibility for the traditionally mainstream Wohngeld has been limited by withdrawing it from recipients of social assistance benefits. In 2017 most of its 600,000 recipients were pensioners, and its cost was only €1.2 billion. However, some four million households now receive support for rent and heating through social assistance, which can meet the cost of the entire rent. These subsidies cost some €17 billion in 2017.Footnote4

Germany’s rental market may have been close to being integrated in the 1990s, but this is clearly no longer the case. The combination of the smaller reach of the cost-rental sector and upward pressure on market rents has led to a greater reliance on regulatory interventions in the for-profit sector. This would simply mark a retreat to a unitary market if it were not for the changing nature of the cost-rental sector. Shortages combine with growing need with the result that the remaining stock of (formerly) “first tier” social housing is increasingly targeted on those people who are threatened with homelessness (Droste and Knorr-Siedow Citation2014). Dependence on social assistance to meet rental costs is a further inhibitor of a social market. A key implication of these changes is that Kemeny’s theory no longer explains Germany’s rental or wider housing system because the relationship between the cost- and for-profit rental sectors is no longer the key dynamic.

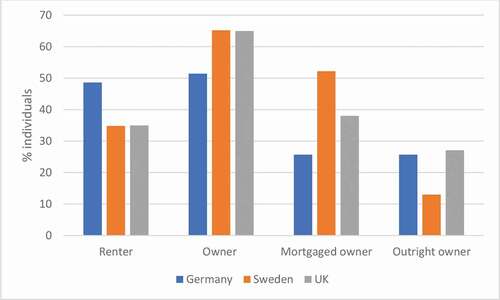

Nonetheless, although the rental sector has become more segmented, in a wider housing market sense, a kind of unitary housing system remains. Germany is one of the few western countries to have resisted the rise of owner-occupation, in particular, that financed through mortgages. This has been attributed to lack of demand (frequently attributed to risk aversity as well as relative incentives – e.g. BNP Citation2016) rather than institutional inertia (Voigtänder Citation2009). Just over one-quarter (25.7%) of individuals live in households in mortgaged ownership, whilst the same proportion of individuals are outright owners (). Overall Germany’s fragmented rental sector has retained the ability to compete with home-ownership: it houses almost half the population, including 43.7% of those who are not poor ().

Table 5. Tenure of individuals not living in poverty

Figure 3. Tenure, 2017

4.2 Sweden

4.2.1 Context

The Swedish social and economic model was developed during the 40-year period of Social-Democratic hegemony that ended in 1976. In the 1930s, the Social Democrats were able to widen the party’s base “from a party of class struggle … to a national party, capable of presenting itself as the bearer of a truly national project [known as folkhemmet – the people’s home]” (Rojas Citation2005, p. 21).Footnote5 The party built corporatist structures centred on the 1938 Saltsjöbaden Agreement between the trade unions (Landsorganisationen, LO) and employers’ federation (Svenska Arbetsgivareföreningen, SAF). What became known as the Rehn-Meidner model (named after two LO economists) used centralized wage bargaining to constrain wage growth and reduce pay differentials (“equal work for equal pay”) in the context of full employment. This allowed successful companies (which remained in the private sector) to reinvest profits for future expansion. Those workers made unemployed in uncompetitive industries were provided with high levels of social protection and retraining, although the state became an increasingly important employer as collective consumption expanded with the welfare state in the 1960s (Iversen Citation1998). The model began to fail from the late 1960s, as the principle underpinning wage settlements shifted from “equal work for equal pay” to “equal pay for all” and the LO launched a controversial campaign for “wage-earner funds” that would be built up to take-over profitable industries. These were introduced in a diluted form (Vartiainen Citation1998).

Employers responded by disengaging from the centralized wage bargaining system, which oversaw a wage explosion in the mid-1970s and substantial “wage drift”. The centralized wage bargaining system was dismantled in the 1990s. Meanwhile, the model had come to rely on high tax rates and high levels of public spending. By 1993, the public sector accounted for 43% of employment and public expenditure reach 73% of GDP (Rojas Citation2005). Macroeconomic policy was based on a soft currency with periodic devaluations aimed at restoring economic competitiveness.

The Swedish model reached a critical juncture in the early 1990s with the economic and banking crisis. Of symbolic as well as material importance was the end to full-employment as unemployment rose to 12.6% in 1994 (Rojas Citation2005). Although the centre-right government in the early 1990s made budget cuts, it was Göran Persson’s Social-Democratic administration (1996–2006) that introduced a series of reforms. These included allowing a role for the private sector in the provision of education and the privatization of utilities, transport and postal services. Although Swedes voted against joining the European single currency, the central bank (Riksbank) was granted independence in 1999 and charged with pursuing a policy of inflation-targeting. Since the GFC it has been pursuing an aggressively loose monetary policy involving negative interest rates and a programme of quantitative easing, with a consequent upward pressure on property prices. Politically, the rise of the anti-immigrant Swedish Democrats (Sverigedemokraterna) has destabilized politics because mainstream parties will not enter a coalition with a racist party.

The Swedish labour market now sustains high levels of male and female employment (), both in excess of the OECD average, and the growth in part-time employment has not been to the extent seen in Germany. However, Sweden’s status as having the lowest level of poverty in Europe is now over. In the mid-1990s only 7% of Swedes lived in poverty (). This rose slightly to 9.5% in 2005, and to 15.7% in 2017 () – bringing it close to German and UK levels. The extent to which the distinctive Swedish welfare system has declined is demonstrated by the convergence in poverty rates across the three countries, both before and after redistribution through taxes and social security ().

4.2.2 The Swedish Housing System

Swedish housing policy is underpinned by the cross-party agreement that the country should avoid creating a “social” model of housing, involving the targeting of social housing on low-income households (Lind Citation2014). The idea of tenure neutrality informed the creation of the Swedish model in the 1940s when cross-tenure subsidies were introduced and rent control introduced. These subsidies underpinned the Million Homes programme of ca. 1965–74 at the end of which the government explicitly confirmed its commitment to equal standards and costs across the tenures (Christophers Citation2013).

The non-profit sector is represented by Municipal Housing Companies (MHC), which are owned by, but managed independently of, local authorities. This sector reached parity with the for-profit sector by the mid-1960s (Kemeny Citation1995), a situation that has more or less been maintained since then (Lind Citation2014). Since 1968, rent setting in MHC and private rental sectors has been based on “use values” which implies a high degree of rent pooling, although in reality, the extent to which this happens varies between municipalities. The tenants’ union (Hyresgästföreningen, SUT) is resistant to above-cost rents being charged on older properties. An explicitly corporatist mechanism applies to rent setting, which is determined by annual local negotiations between SUT and the MHC, and since 2011 the private landlords, too. Rent setting in the MHC is therefore used as the basis of rent setting in the for-profit sector – so by regulation “lead” rent setting in the rental market as a whole. The end of the Million Homes programme has allowed the MHC sector to mature.

In his 1995 book, by which time housing subsidies were being phased out in response to the economic crisis (Turner and Whitehead Citation2002) and some municipalities were beginning to sell a stock, Kemeny remained of the view that there had been no fundamental shift away from the commitment to cost-renting. He reviewed the situation in Sweden in his 2005 article in which he maintained that

“ … progress towards an integrated market that will enable non-profit companies to compete with profit landlords without regulatory restrictions has been considerable in the last three ‘consolidation decades.’” (Kemeny Citation2005, p. 866)

However, he did acknowledge a number of “retrograde threats”, which included the sale of MHC properties and that lack of new-build investment (attributable in part to the hostility to cross-subsidizing new build from older properties). Nonetheless, he concluded that “… progress from [a] unitary to integrated [market] is at best crab-like (or perhaps more like two steps forward and one step back)” (ibid., p. 867).

Our assessment is that in the 1990s and in 2005 (the date of Kemeny’s last assessment), Sweden operated a unitary rental market, and the relationship between the cost- and for-profit sectors was a key dynamic. However, it is not clear that there was “progress towards an integrated market” as there was no notable reduction in regulation that indicated the shift from regulatory to market power to unify the rental market. Certainly, had regulation been removed, one would have expected the MHCs to have exercised considerable market power, which is perhaps what Kemeny meant.

There is, however, a need to examine a crucial element in Kemeny’s theory which is that in unitary rental markets, the rental sector is able to compete against owner-occupation. Owner-occupation in Sweden had been restricted to family houses, until 1968 when the status of owner-co-operatives changed. Previously, they could be sold only at use value, but thereafter they could be traded at exchange value. Being both freely tradable and mortgageable, the change effectively extended owner-occupation into the apartment sector. The deregulation of the mortgage market in the 1980s facilitated the growth in mortgaged home-ownership leading to a boom-bust cycle that contributed to the banking and economic crisis of the 1990s. Further property taxation now favours ownership over renting, too (Christophers Citation2013). Certainly, by 2005, most Swedes lived in mortgaged home-ownership (54.9%) and the overall home-ownership rate exceeded two-thirds (68.1%) (Eurostat Income and Living Conditions, variable ilc_lvho02).

4.2.3 The Changing Swedish Housing System

Since the 1990s, the trend has been strongly against the maintenance of a functional unitary rental market and this has undermined further the ability of renting to compete with ownership.

First, the scale of the MHC sector has shrunk and with it its ability to influence the rental market as a whole via market power. This has been most acute in the three largest cities where demand pressures are greatest. Housing output fell as a result of the withdrawal of subsidies from MHC in the 1990s and the private sector has never filled the gap (OECD Citation2017). The government has introduced new subsidies to support the construction of rental housing in pressurized markets over the 2015–20 period, but this does not mark a return to the use of MHC as the vehicles for shaping the housing market (OECD Citation2017).

Moreover, sales of MHC properties have substantially reduced the stock not only in Stockholm (Lind Citation2014) but across the country. In excess of 100,000 units were sold between 2002 and 2015, mostly to private landlords, but a substantial minority shifted to the tenant-owner sector (Boverket Citation2017, Diagram 2.2). This suggests that rental surpluses are being extracted contrary to the principles of a unitary market and this weakens the ability of the non-profit sector to “lead” the for-profit sector by competition.

This means that there is a greater reliance on regulation to maintain a unitary rental market, but rent setting in the for-profit sector has been relaxed somewhat as rents can now be based on those in similar apartments in both sectors, rather than just the (lower) MHC rents (Christophers Citation2013). This is suggestive of a weakening of the regulatory influence of the MHCs over the for-profit sector rents.

However, the key disruptive dynamic arises from the shortage of both MHC and private rental housing. The “unitary” market may still function for “insiders”, but a different dynamic applies to “outsiders” for whom access is restricted. People with contracts are reluctant to surrender them and if they wish to move will instead often trade their tenancies or sublet the property (legally or illegally) (Lind Citation2014). Access is, therefore, more dependent on an informal rental market, often at market rents, composed of series of second-hand contracts or sub-lets, and predictably there is a black market, too (Christophers Citation2013). The knock-on effects on the demand for owner-occupied housing are discussed further below.

The commercialization of MHC objectives after 2011 occurred to avoid EU intervention arising from the competitive advantage they enjoyed over the for-profit sector provided by loan guarantees. Faced with a choice between adopting a “social” model targeted at poorer households, or behaving like normal businesses, the Government and MHC favoured the second option. Consequently, MHC are now expected to operate in a more “business-like” way, whilst not subjecting access to a maximum income (Elsinga and Lind Citation2013).

This decision might be interpreted as the “critical juncture” at which the decisive decision was made to retain a notional “housing for all” model. However, the dynamics have produced a distinctive allocation pattern. MHC have always been reluctant to house the poorest and most vulnerable households, using mechanisms such as minimum income requirements and references to restrict their access, or at least divert them to less popular stock (Fitzpatrick and Stephens Citation2014). Particularly since 2011, these mechanisms have been intensified, for example, by excluding people reliant on housing allowances, so pushing allocations upmarket (Grander Citation2017). This, within the context of rising poverty, has increased the reliance on the “secondary” market, whereby municipalities lease properties from MHC and private landlords to house poor and vulnerable households, but on terms inferior to those of mainstream tenants. Those in the middle are being squeezed out of the MHC sector, whilst the overall effect has been towards residualisation, particularly in municipalities with smaller public housing sectors (Borg Citation2019).

The disruption of the rental market has caused people to turn to home ownership – to the extent that they can afford to. Overall, home-ownership has fallen back a little to 65.2% in 2017 (compared to 68.1% in 2005), but most Swedes still live in properties that are owned with a mortgage (). Lind comments that “Young households with reasonable incomes are … often ‘forced’ into the ownership market, especially if they want to live in more attractive areas where waiting times are longer” (Citation2014, p. 996). This is an important dynamic that Kemeny attributes to the dualist rental systems. Further, one in six Swedes who live in poverty are mortgaged owners – a similar proportion to the UK (), although in both countries, the proportions have fallen significantly since the GFC. Yet this remains another clear breach of the predicted tenure pattern arising from a unitary rental market.

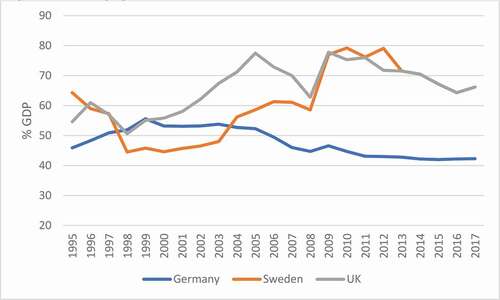

Further, mortgage debt as a share of GDP has risen from 44.5% in 1997 to 66.2% in 2017 (), confirming housing’s increased role as a liquid financial asset.Footnote6 This shift towards a financialised home-ownership sector is significant because once rising asset values become an important element in home-ownership, there can be no neutrality between owning and renting.

Figure 4. Mortgage debt as a share of GDP

Formally, the institutional structure of the Swedish housing model has been largely maintained, but the unitary rental market has collapsed from within, undermined by market pressures arising from shortages, the rise of ownership, and the weakening of the supportive architecture of relative equality that was provided by the social-democratic social and economic model. The relationship between the cost and for-profit rental sectors is no longer the key dynamic in the Swedish housing system, and in this crucial sense the theory has lost its explanatory power.

4.3 The United Kingdom

4.3.1 Context

The UK’s social and economic system has experienced two broad phases in the postwar period. The 30 years up to the mid-1970s are often referred to as the era of the “social democratic consensus” in which both main political parties supported a Keynesian macro-economic policy and supported the institutions of the welfare state that were introduced by the 1945–51 Labour Governments. This was a period of steady economic growth and falling income inequality. Workers’ rights were protected by collective bargaining between trade unions and employers, without resort to corporatist structures. The postwar social insurance system contrasted to much of continental Europe and Scandinavia by providing flat-rate benefits or “flat-rate universalism” (Esping-Andersen Citation1990, p. 25). The “rediscovery of poverty” in the early 1960s (Gazeley Citation2003) prompted the introduction of a series of social assistance benefits. The relative decline in economic performance in the 1970s, combined with government attempts to contain wage inflation through statutory prices and income policies, contributed to the industrial conflict which exploded spectacularly in the “winter of discontent” in 1978/79.

Although the election of the Thatcher government in 1979 symbolized the break with the social-democratic consensus, it had effectively ended in 1976 when the economic crisis forced the government to take out a loan from the IMF whose conditions required expenditure cuts. The Thatcher government’s economic policy of “monetarism” was intended to control inflation, but the policy of high interest rates led to an overvalued currency, rapid deindustrialization and a large growth in unemployment.

Subsequently, the economy restructured with a growth of services. The labour market became more feminized, particularly in part-time jobs, and eventually polarized into “work rich” dual-earner households, and “work poor” no earner households. Poverty and income inequality rose rapidly after bottoming out in the mid-1970s. Social security was reformed and became more dependent on social assistance benefits. The Labour Governments of 1997–2010 attempted to tackle poverty through means-tested tax credits for working households, and a much more generous social assistance system for pensioners, which successfully lowered the pensioner rate of poverty below the average for the first time. The austerity programme pursued by Conservative and Conservative-led governments since 2010 has focussed on reducing the deficit after the Global Financial Crisis, and have greatly increased conditionality among the growing spectrum of claimants who are expected to work, resulting in a much greater use of sanctions and a huge growth in the use of food banks. Benefits have also been cut for people with disabilities, but pensioners have largely been protected. Due to the suppression of median incomes, poverty has declined since the mid-1990s (). However, there has been a rise in destitution (Fitzpatrick et al. Citation2016).

4.3.2 The UK Housing System

The postwar housing policy in the UK focussed on public rental housing owned and managed by local authorities, which already been established as significant providers in the inter-war period. From the 1950s subsidy was shifted to focus on replacing sub-standard slum housing, which marked a shift away from the “universal” model promoted in the early postwar period. The standard of council housing also declined from the very high standards set in the 1940s, and additional subsidies were provided to encourage local authorities to build a high-rise. So, although a broad spectrum of the population lived in council housing, by the 1960s many aspirational families were increasingly opting for home-ownership. Meanwhile, the private rented sector was mostly subject to security of tenure and rent control, and by the 1970s was a residual tenure characterized by housing a mixture of older households, and younger mobile people. Certainly, the notion that the social rented sector was kept separate to provide shelter the for-profit sector does not hold, at least until the 1990s, as it was subjected to onerous regulation.

By the time of the IMF economic crisis and subsequent Thatcher revolution arrived, the rental sector was already “dualist” in nature. However, the primary cleavage was between the two tenures that were growing at the expense of for-profit renting, namely social renting and owner-occupation. So, although the rental sector could be described as being “dualist”, this dynamic was not the central driver of the housing system. More importantly, the aspiration for home ownership was strong and the combination of the subsidized sales policy (Right to Buy) introduced for council tenants in 1980, and the deregulation of the mortgage market in the early 1980s leading to a greatly increased availability of mortgage finance, set the course of housing system change for the next 25 years. Home-ownership grew (until 2006), private renting continued to decline (until the 1990s), and council housing declined, due to sales and much-reduced subsidies for building. From 1989 (in England) surpluses in local authorities’ housing revenue accounts were systematically extracted by Government, encouraging a wave of stock transfers to housing associations, which were also chosen by the government to be the main providers of new social housing. The social rented sector became increasingly residualised, for a variety of reasons, which included the effect better off tenants buying their properties, and local authorities increasingly targeting allocations on people who were in greatest housing need, including the (unintentionally) “statutory homeless” in priority need whom they had a duty to rehouse from 1977. The sector, therefore, provided a secure and long-term “safety net” for a broad range of poorer households (Stephens, Burns, and McKay Citation2003).

4.3.3 The Changing UK Housing System

It should be noted that the crisis-induced changes in the UK housing system occurred earlier than in Germany or Sweden and were captured in Kemeny’s work. The changes observed here are therefore those that have occurred after Kemeny’s assessments.

The housing system changes further with the revival of the private rented sector, after new tenancies were freed from rent control and fixed-term tenancies were introduced in 1989. As house prices rose after the mid-1990s, more people became priced out of home-ownership. Whilst the headline rate of home ownership did not begin to fall until 2006, the falls among younger households were deeper seated and more dramatic. Whilst the UK was an early exemplar of a housing system where mortgaged owner-occupation was a key feature, this is no longer true to the same extent ( and ). The nature of private renting changed and now houses a broader section of the population, including families with children (Stephens and Stephenson Citation2016). Meanwhile, loose monetary policy and unorthodox quantitative easing have been hallmarks of post-GFC policy, deliberately supporting asset prices. In what follows, the discussion relates to England only, due to growing divergence in housing policy within the UK (Stephens Citation2019).

Whilst the private and social rented sectors remain distinct (hence “dualist”), it is policy and practice that is changing the social rented sector, although it has little influence on the rest of the housing system. The social rented sector began to change with the election of the Conservative-led coalition in 2010 and the Conservative majority government elected in 2015. Initially, subsidies were shifted away from providing new social rented housing and low-cost home ownership to affordable housing with rents set up to 80% of the market (in England). A “reinvigorated” Right to Buy programme (with larger maximum discounts) and a new (but now abandoned) policy of mandatory “pay to stay” to make higher-income tenants pay market rents are intended to encourage sales to better off tenants (Perry Citation2019). The Government is also running a pilot to introduce Right to Buy into the housing association sector. The legislation was passed to introduce mandatory fixed-term tenancies, based on the supposition that social rented housing should not provide housing for life. Had these policies been enacted they would have marked a move away from the safety net model, to the “ambulance service” model seen in the USA and Australia. However, the Government backed off making them obligatory, although many social landlords choose to use them for new tenants (Perry Citation2019).

5. Discussion: How Housing Systems are Changing and Why

In each of the three countries, economic crises or perceived economic underperformance prompted far-reaching reforms to the wider welfare system represented by the labour market and the tax and social security systems. In the UK, the critical juncture occurred with the IMF crisis of 1976, in Sweden following the banking crisis of the early 1990s, and in Germany following the underperformance of the economy of the late 1990s. Each spawned reform that weakened organized labour, ended centralized wage bargaining, and represented at least a partial acceptance of neo-liberal logic. Later, the decay in underlying ideologies is reflected in the weakening of traditional centre-right and centre-left parties, and the rise of populist or anti-immigrant rivals (e.g. Rydgren and Van der Meiden Citation2019). Labour market and social security reforms introduced in the three countries have led to a convergence in both employment and poverty levels. Distinguishing features of “classic” welfare regimes such as Germany’s “male breadwinner” model and Sweden’s egalitarianism are no more. Poverty rates in the three countries have converged towards the higher levels that were once a distinguishing feature of the UK. In theoretical terms, welfare regimes were changing leading to changes in welfare systems.

Meanwhile, the unitary or integrated rental markets of Sweden and Germany have decayed from within for two principal reasons. First, they decayed as a result of the implosion of the subsidy-maturation nexus. The failure to anticipate the necessity of subsidy in maintaining the new supply of cost-rental housing and instead to rely on maturation is perhaps the most significant factor in weakening the ability of the cost-rental sector to influence and shape the rest of the housing system. We may think of this as Kemeny’s Panglossian error (of over-optimism) to be contrasted with the Romeo error (of over-pessimism) with which he charged his critics. Second, the temptation to sell off municipal housing assets occurred in Germany and Sweden. Both of these phenomena may be thought of as being part of a process parallel to that occurring in the wider welfare system, indicative not only of policy but the values that underpin it – in other words, the overarching welfare and housing regimes.

Second, Kemeny’s misspecification of the relationship between housing and wider welfare regimes is highlighted by the role that welfare system reform played in changing housing systems. When levels of poverty are low and the supply of cost-rental housing sufficient, it is possible to operate a cost-rental sector that is open to a large cross-section of society and to allow quasi-market signals (such as demand-sensitive rents) to operate without causing undue hardship on the poor. In contrast, when poverty rates are high and supply of cost-rental housing is constrained, “housing for all” must mean housing for some, but not others. The policy choices made by the government and landlords then become vital to determining the nature of the housing system. In Germany municipal housing has become more targeted on poorer households. In Sweden, the decision by MHCs to move “upmarket” by raising barriers against low-income applicants has prompted a greater reliance on the “secondary” market whereby local authorities lease housing on behalf of low-income tenants with terms inferior to those enjoyed by mainstream tenants – a dualist cost-rental system mocking the very notion of a unitary rental market. In the UK, the “safety net” role of the social rented sector has been vital in a country with enduringly high levels of poverty, and the near adoption of an “ambulance service” model in England emphasizes the vital role of policy choice.

Thus, undermined from within and from outwith, integrated rental markets, attained by the effective competition from the cost-rental sector, have broken down. The shrinkage of the cost-rental sector in Germany has enfeebled its market power, with the result that, wholly contrary to the social market tradition, greater reliance is placed on direct regulatory mechanisms in an attempt to retain a unitary rental market, which has itself fractured as cost-rental housing is targeted on the poor. In Sweden, the rental system remains unified by corporatist mechanisms, but fatally undermined by shortages, waiting lists and informal markets.

But, in addition to the changes occurring within rental sectors and the context of the wider welfare system, the globalization of finance exerted further pressure especially on the UK and Swedish both which deregulated mortgage finance in the 1980s, which facilitated the growth in mortgaged home-ownership. The global shift towards low-interest rates and consequently the “search for yield” made the property an attractive investment in Germany too, albeit in the rental sector, and was further enhanced by the adoption of aggressive and unorthodox monetary policies in response to the Global Financial Crisis, which places upward pressure on property prices.

The crucial test of a unitary housing system is whether the rental sector is able to compete effectively with home-ownership, and (now) to do so under the conditions of financialisation whereby debt is used to strengthen the role of housing as an asset above that of a consumption good. Manifestly, this is not the case in Sweden whose housing system has become increasingly defined by mortgaged home-ownership. High levels of home-ownership, including a significant proportion of the poor, were singled out by Kemeny as being a feature of dualist systems such as the UK. Now mortgaged ownership rates among the Swedish poor rival those in the UK.

In contrast, Germany’s rental system continues to offer a sufficiently attractive alternative to home-ownership. Financialisation may have occurred within the rental sector, but financial incentives, institutional structures and apparent risk aversity mean that mortgaged home-ownership rates remain low. Clearly, a substantial proportion of the non-poor live in rental accommodation through choice. However, it is only in this narrow sense there is a unitary housing system is maintained; it is dependent on regulation, and has little to do with the influence of the cost-rental market.

6. Conclusions

Kemeny’s theory marked a unique and outstanding contribution to the understanding of housing systems. It sought to demonstrate that under certain circumstances the whole housing system could be shaped by the cost-rental sector and its relationship with the for-profit sector. In our assessment at the time that Kemeny was writing this was the key causal dynamic in Germany and Sweden, although not in the UK. However, since then the two unitary rental markets examined here broke down not just because things changed, but because the theory was in places mis-specified. The relationship between housing and the wider welfare regime was misunderstood, the belief that maturation would counterbalance the loss of subsidy misplaced, and the refusal to accept the power of high-level forces of convergence associated with globalization myopic, whilst the post-GFC era of unorthodox monetary policy was unforeseeable.

What lessons are there for theory?

First, the efficacy of the general housing-welfare regime approach is largely (if not wholly) confirmed. Balances of power, ideological or cultural preferences, their formal expression through voting and their mediation through institutions create the regimes that spawn welfare and housing systems. When the regimes changed, the systems necessarily followed. We have also sought to establish that the relationship between the housing and the wider welfare system, which includes labour market as well as social security (so is broader than the welfare state) plays a crucial role in housing systems and their change. Welfare systems have necessary (or causal) distributional tendencies which set the parameters (“boundaries of possibility”) within which a social rented sector can operate as providing “housing for all”, a long-term safety net for people on low incomes or an ambulance service of temporary assistance for the most desperate people. In turn, the housing system plays an important role in determining overall distributional outcomes since those arising from the housing system can replicate, exacerbate, or counter those of the wider welfare system (see Stephens and van Steen Citation2011).

Second, the housing welfare-regime approach does, however, need to be extended. The relationship between the housing system and the institutions of monetary and financial policy needs to be incorporated into our understanding of housing systems. The globalization of finance was crucial to the financialisation of housing in the years up to the GFC. As a consequence of the GFC, central banks have become more influential as their role associated with the “technical” exercise of targeting consumer price inflation has widened as monetary policy – both orthodox and unorthodox – has become the core instrument of macroeconomic policy. Their role in utilizing unorthodox monetary policy to support asset values contributes to the ongoing advance of financialisation.

These observations point to the limitations of theories of the middle range, and hence the housing-welfare regime approach. Understanding housing systems requires scholars to look beyond the middle range, upwards to embrace high-level forces of convergence, and downwards to consider institutional details (such as housing allocation policies) that explain differences. They also suggest that although globalization of finance acts as a powerful force for convergence, simple convergence theories are inadequate because convergent forces are mediated through distinct (and path dependent) institutional structures and are subject to the continued role of policy choice. Whilst this may point to “soft” convergence, it is not clear – empirically – that housing systems are actually converging at all. Indeed, a counterintuitive observation is that as the policy environment has become more constrained, the importance of policy choices has been amplified, reflecting the more acute trade-offs and consequences for more economically vulnerable populations.

There is, however, a final conundrum. If the underlying cause of welfare or housing regimes is the ideological underpinning of liberalism, social democracy, or conservatism, finding formal expression in political parties and other (corporatist) institutions, then how do we understand them as these foundations are weakened? Stephens, Lux and Sunega (Citation2015) highlighted this problem in interpreting post-socialist housing systems where no clear ideology replaced socialism, but this now extends to the former heartlands of social democracy and corporatism. Neoliberalism is too looser shirt to provide a convincing explanation and is in any case challenged by populism. This is an important challenge for the future.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by the UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence, a research centre funded by ESRC, AHRC and the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (grant reference: ES/P008852/1). I am grateful to many people for providing information and/or comments on earlier drafts of this paper. They include Volker Busch-Geertsema, Jennie Gustafsson, Thomas Knorr-Siedow and Rolf Müller. I am also grateful to Terry Hartig for his detailed editorial comments. Responsibility for errors of fact or judgement remains my own.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. This refers to the system of poor relief developed in the UK in the nineteenth century, known as the “poor law”. It was based on the principle of “less eligibility” meaning that the living standards within a workhouse for the poor should be worse than the standards outside it (Gazeley Citation2003, pp. 10–11). Kemeny presumably used the term for effect to make a general point about residualisation in public housing, rather than meaning it literally.

2. The probable explanation for this discrepancy is that the paper published in English in 2006 was originally published in Swedish in 2003.

3. In contrast to other formerly socialist housing systems, only a relatively small proportion of public rental housing in the former German Democratic Republic was sold at discount to tenants. Much was sold to German institutional and international investors.

4. I am grateful to Rolf Müller for providing these statistics.

5. Contrary to Kemeny’s speculation that Sweden was influenced by ordo-liberalism, I can find no evidence of this in the literature.

6. Minimum levels of amortization have been required since 2016.

References

- Aalbers, M. B. 2016. The Financialization of Housing. A political economy approach, Abingdon: Routledge.

- Atkinson, R., and K. Jacobs. 2016. House, Home and Society. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

- BBC. 2019. “Berlin Protests: Thousands Gather for March against Rising Rent Prices”, 6 April

- Bengtsson, B. 2001. “Housing as a Social Right: Implications for Welfare State Theory.” Scandinavian Political Studies 24 (4): 255–275.

- Bieler, A. 2013. “Austerity and Resistance: The Politics of Labour in the Eurozone Crisis.” Social Europe 11 (July).

- Blackwell, T., and S. Kohl. 2019. “Historicizing Housing Typologies: Beyond Welfare State Regimes and Varieties of Residential Capitalism.” Housing Studies 34 (2): 298–318.

- BNP. 2016. Germany: Thrifty and Risk Averse. Paris: BNP.

- Borg, I. 2014. “Housing Deprivation in Europe: On the Role of Rental Tenure Types.” Housing, Theory and Society 32: 73–93.

- Borg, I. 2019. “Universalism Lost? the Magnitude and Spatial Pattern of Residualisation in the Public Housing Sector in Sweden 1993-2012.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 34: 405–424.

- Boverket. 2017. Allmännytta samt hyreslagstiftning [Public utility and rental legislation], Karlskrona: Boverket

- Castles, F. G. 1998. “The Really Big Trade‐Off: Home Ownership and the Welfare State in the New World and the Old.” Acta Politica 33 (1): 5–19.

- Christophers, B. 2013. “A Monstrous Hybrid: The Political Economy of Housing in Early Twenty-first Century Sweden.” New Political Economy 18 (6): 885–911.

- Clapham, D. 2019. Remaking Housing Policy: An International Study. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Clasen, J. 1997. “Social Insurance in Germany – Dismantling or Reconstruction?” In Social Insurance in Europe, edited by J. Clasen, 60–83. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Droste, C., and T. Knorr-Siedow. 2014. “Social Housing in Germany.” In Social Housing in Europe, edited by K. Scanlon, C. Whitehead, and M. F. Arrigoitia, 183–202. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

- Elsinga, M., M. Stephens, and T. Knorr-Siedow. 2014. “The Privatisation of Social Housing: Three Different Pathways In.” In Social Housing in Europe, edited by K. Scanlon, C. Whitehead, and M. F. Arrigoitia, 390–413. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

- Elsinga, M., and H. Lind. 2013. “The Effect of EU-Legislation on the Rental Systems in Sweden and the Netherlands.” Housing Studies 28 (7): 960–970.

- Esping-Andersen, G. 1990. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Federal Government of Germany. 2019. “What Is the German Government Doing for the Housing Market?”, August

- Fitzpatrick, S., G. Bramley, F. Sosenko, J. Blenkinsopp, S. Johnsen, M. Littlewood, G. Netto, and B. Watts. 2016. Destitution in the UK. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Fitzpatrick, S., and H. Pawson. 2014. “Ending Security of Tenure of Social Renters: Transitioning to ‘Ambulance Service’ Social Housing?” Housing Studies 29 (5): 597–625.

- Fitzpatrick, S., and M. Stephens. 2014. “Welfare Regimes, Social Values and Homelessness: Comparing Responses to Marginalised Groups in Six European Countries.” Housing Studies 29 (2): 215–234.

- Gazeley, I. 2003. Poverty in Britain 1900–1965. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gibb, K., D. Maclennan, and M. Stephens. 2013. Innovative Financing of Social Housing. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Grander, M. 2017. “New Public Housing: A Selective Model Disguised as Universal? Implications of the Market Adaptation of Swedish Public Housing.” International Journal of Housing Policy 17 (3): 335–352.

- Guerot, U., and S. Dullien. 2012. “The Long Shadow of Ordoliberalism.” Social Europe 30 (July).

- Harloe, M. 1995. The People’s Home. Social Rented Housing in Europe and America. Oxford: Blackwell.