ABSTRACT

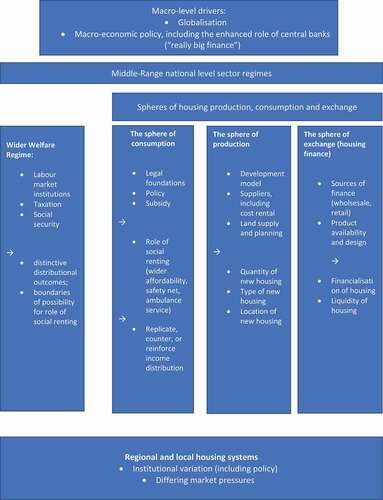

In this article I respond to commentators’ observations relating to my Focus Article, “How housing systems are changing and why”, and propose a multi-layered housing regime framework. I argue that the institutions of housing system are naturally located in the middle-range, and fall into three distinct spheres of production, consumption and exchange. These spheres interaction with the “wider welfare regime” which represents the institutions of the labour market, taxation and social security. They have distinctive distributional tendencies and set the “boundaries of possibility” of the social rented sector’s role. Sitting above these middle-range institutions are macro-level drivers including macro-economic policy and the relatively new phenomenon of “really big finance” implied by unconventional monetary policies adopted by many central banks. Beneath the middle-range institutions lie regional and metropolitan markets where institutional variations and market pressures may produce intra-regime variation of outcomes.

1. Introduction

It is a great privilege to be given the opportunity to present a critique of Jim Kemeny’s theory of housing regimes in a Focus Article published in the journal of which he was founding editor in its present form. The news of Jim’s death means that I feel also great sadness at this loss to the community of housing scholars.

Like many academics, my work has been greatly influenced by Jim Kemeny. He invited me to a workshop at the European University Institute in Florence in 1999 where I presented a rudimentary version of the thesis concerning the relationship between housing systems and the wider welfare regime that I have been developing since then. Jim was at first puzzled by my hypothesis that changes to the labour market and social security system could fundamentally affect the operation of the cost rental sector, but he acknowledged by email the development of this idea when it was published in Stephens, Burns, and MacKay (Citation2003).

Jim was not a great conference attender, which means that his rare appearances tended to make an impact. He made a memorable contribution to a plenary session at the 2004 European Network for Housing Research (ENHR) conference in Cambridge, and the last time I saw him was when he joined on-line an ENHR Comparative Housing Policy Working Group conference organized by Marja Elsinga and Richard Ronald at TU Delft in 2010.

In offering a critique of Kemeny’s theory of housing regimes as a means of explaining how housing systems are changing, I was conscious of a responsibility to represent his arguments accurately and to critique them with the constructive purpose of advancing understanding of housing system change.

I am therefore grateful to the contributions of the seven scholars who took the trouble to read my article and to provide commentaries on it, and equally I am grateful to the editors for the opportunity to respond to them.

In this response I first seek to summarize Kemeny’s thesis and my critique of it. I then summarize the commentators’ arguments, then to address the most substantive points, and finally to reflect on them in a concluding section to propose a new multi-layered housing regime framework.

2. Summary of Arguments

2.1. Kemeny’s Thesis

Kemeny argued that the design of a cost-rental sector could shape the entire housing system through its relationship with the market rental sector. Given the tendency of cost rental systems to mature as debt is repaid and construction is run down as shortages are met, governments encounter a critical juncture at which point they must decide whether to extract surpluses or allow the cost rental sector to retain them. Where they are extracted a dualist rental system emerges in which the cost rental sector is reserved for the poor and run as a command economy. Having no purchase over the market rental sector, households are encouraged into home-ownership which becomes the tenure of (constrained) choice. In contrast where surpluses are retained, what might have been a unitary rental system dependent on regulation and subsidy, gives way to an integrated market in which the cost rental sector competes with the market rental sector, so forming an integrated market capable of competing with home-ownership. What began as a theory of rental regimes became a theory of housing regimes in which the underlying drivers are power balances and attendant societal ideologies.

2.2. Stephens’ Critique

My review suggested that in the 1990s his identification of dualist (UK) and unitary (Germany, Sweden) rental systems plausibly represented the reality. However, whilst the dualist/unitary nature of rental systems was confirmed, they were found to define the nature of the housing system in Germany and Sweden, where integrated markets emerged, but not in the UK where the defining feature of the system was the division between cost rental housing and home-ownership. I further suggested that unitary or integrated systems in Sweden and Germany had since broken down. External factors included the failure (or perceived failure) of social and economic systems that can be attributed to globalization, leading governments to introduce labour market and social security reforms that increased poverty. Crucially, this curtailed the ability to operate cost rental sectors as social markets, making trade-offs between “housing for all” and targeted allocations policies more acute.

Integrated housing systems were further weakened from within. A key internal factor in both Sweden and Germany was that government began to extract rental surpluses through mechanisms such as stock sales, and this was reinforced by subsidy withdrawal which meant that cost rental sectors failed to reproduce themselves, so weakening their influence. In Sweden, acute shortages in the rental sector led the rental market to become dysfunctional, whilst financial liberalization facilitated the growth of mortgaged ownership, with asset prices further boosted by the adoption of unconventional monetary policies after the Global Financial Crisis. However, in Germany, despite the enfeeblement of the shrinking cost rental sector, the market rental sector has continued to compete with home-ownership partly through greater use of regulation, but also through apparent cultural resistance to mortgage debt.

The lessons that I drew for theory were that middle range housing theories such as Kemeny’s need to take account of their embeddedness within what I call the wider welfare regime, to acknowledge high-level forces of convergence such as globalization, whilst also recognizing the importance of institutional detail. Finally, I left open a consideration of the consequences for regime theory of the decline in the political ideologies (such as social democracy) that defined social and economic systems that spawned the distinctive housing systems under review, noting that “neoliberalism” is too loose a shirt to provide an adequate explanatory replacement.

2.3. Commentators’ Observations

The commentators present a wide range of views, ranging from a general endorsement of the thesis to a wholescale rejection of regime approaches.

David Clapham provides a fulsome engagement with the thesis, and relates it to his own developed in his recent book (Clapham Citation2019). The core of Clapham’s critique, at least as I understand it, revolves around to what extent drivers of change can be characterized as being internal or external to the housing system. Clapham’s tendency is to place a greater emphasis on the importance of external drivers and to interpret what I identify as being internal drivers as really being driven by external ones. He concurs with my assessment that middle-range theories need to be extended upwards and downwards, and interprets this as a de facto endorsement of his own suggestion that change can be understood only by “[taking] elements from a range of theories including welfare regimes, path dependence and financialisaton without being based on one or the other.” (Clapham Citation2020, this issue). In response to my complaint that neoliberalism being too looser shirt to provide an adequate explanation, Clapham characterizes it here as being one of a number of factors that needs to be considered. He therefore seems to downplay the central role it enjoys in his book in which it is “a discourse, a set of powerful ideas that are sustained and used by powerful agents to further their interests” (Clapham Citation2019, 2). (See also the review of Clapham, Citation2019, by Stephens Citation2020).

Michelle Norris concurs that housing regime theory “undoubtedly has more explanatory power than high level theories … such as neo-liberalism and financialisation, which if handled clumsily simultaneously explain everything and nothing” (Norris Citation2020, this issue), and raises two substantive points. She observes the importance that finance plays in Kemeny’s theory (notably the role of maturation of the cost-rental sector) and the distinctive expenditure profile that this gives housing compared to other welfare services, meaning that “finance regimes are likely to have at least as large a role as welfare regimes in shaping housing systems.” She points to the work of Blackwell and Kohl (Citation2018; Citation2019) and their suggestion that the early development of deposit-based finance in English speaking countries may have been a significant driver of higher home-ownership rates, compared with the bond-financed systems in Denmark and Sweden. Her second suggestion is that countries such as Austria and Denmark might provide useful comparisons with their most similar counterparts, Germany and Sweden.

Marja Elsinga suggests that consideration of the Netherlands would also improve the representation of unitary regimes. She argues that the cost-rental sector in the Netherlands reached a state of “over” maturity to the extent that government sought to correct (“demature”) it through a tax on social landlords, so helping to push the system from being a unitary one towards being a dualist one. She suggests that “it is not a question of maturation but rather how governments deal with it, that is the driver for changing rental systems.” (Elsinga Citation2020, this issue). Elsinga points to “neoliberal thinking” as being the driver behind the landlord tax, and also observes that the fall-out from the European Commission state aid issue (in which government guarantee of housing association debt was seen as being an unjustified state aid) involves the adoption of a new emphasis on targeting cost rental housing on the most vulnerable.

Walter Matznetter, notes my suggestion that unitary/integrated regimes in the countries I examine have broken down (at least in the way that Kemeny described). He makes four substantive points, which lead to his conclusion that there is nothing inevitable about this. First, he endorses Kemeny’s belief that surpluses generated by the cost rental sector in the 1980s and 1990s would be sufficient to finance future new build and renovation, even without subsidy. He attributes the subsequent failure to reproduce cost-rental housing in Germany to a series of “political and economic forces” including the ending of the common interest law and sales of municipal stock. Second, he claims that, “Increasingly, regional to local markets and policies are becoming the appropriate scale for comparative housing research” (Matznetter Citation2020, this issue). This assertion links to a third point. Contending that unitary/integrated systems may have broken down in some areas, he asks (rhetorically) whether such systems might “continue to operate a smaller scales, pushed back to the welfarist pioneer regions of the past?” A fourth point, arising from his lengthy discussion of a report by German consultants on the Vienna market, seems to be that Viennese institutions of corporatism have been maintained and that this might be attributed to the maintenance of a broader “co-ordinated market economy” as a mode of capitalist organization. Hence, so long as the broader institutions of corporatism are maintained integrated markets can flourish.

Jozsef Hegedüs (Citation2020, this issue) divides his contribution into two sections. His general argument is that welfare regimes are too narrow a framework to fully understand housing systems. He believes that Kemeny’s focus on the use of public investment in the rental housing sector and its subsequent maturation is not only a fragile (“delicate”) part of the Kemeny thesis (as I observe), but cannot simply be traced back to “power structure and political ideology”. Echoing Blackwell and Kohl (Citation2019) he points to the role of “the historic/institutional structure of society” in shaping contemporary housing systems, and (more specifically) suggests that a range of public support (including off-balance sheet expenditures) broader than financial subsidy to cost-rental landlords should be considered. He agrees that globalization as an external force is an important influence on housing systems (to the extent that “the explanatory power of mid-level theories is greatly diminished by this fact”), and argues that a greater range of institutional interactions need to be built into an explanatory model of housing.

The second part of the Hegedüs commentary focuses on the (possible) application of Kemeny’s typology to the formerly socialist countries of central and eastern Europe. He argues that “[t]he use of Kemeny’s typology in the socialist countries is very questionable because the rental-housing sector is embedded in an autocratic economic-political system. His discussion marks an important contribution in its own right to the study of housing in this region, and extends beyond the scope of my article. I would observe that Kemeny was clear about the “fairly unique” temporal and geographical application of his model. Hegedüs’ comments do relate to another article I co-authored with Martin Lux and Petr Sunega (Stephens, Lux and Sunega, Citation2015) in which we suggest that it is possible to apply Esping-Andersen-type characterizations of housing (or welfare) systems in terms of the relative role of the state, market or families as sources of welfare in a descriptive sense. However, where there is no obvious underlying ideology (liberal, social democratic, etc.) then the core explanatory element is missing. This is the conundrum that I identify at the end of my article as the former ideological coherence that underpinned distinctive housing systems in western Europe is in decline.

Christine Whitehead brings an economist’s perspective to the discussion. She argues that typologies have four functions: to provide a point-in-time “structured description of a particular topic” and to identify a “set of stable relationships which hold over time” (Whitehead Citation2020, this issue). In turn these may assist the third function, which is to make predictions about the future, and finally to provide an independent variable (“policy packages”) in assessing housing outcomes, and therefore policy development. She then provides commentary on the three case study countries. She suggests that the ability of Germany’s rental sector to compete with home-ownership may be temporary if tougher rent controls lead to transfers into home-ownership, whilst Sweden’s rising poverty rate might be attributable to rising housing costs in the context of a limited housing allowance system. She is more optimistic about England’s ability to resist shifting towards an “ambulance model” of social rented housing, due to the financial strength of housing associations and the revival of building by municipalities. Overall, she points to the weakening of political institutions supportive of a “positive approach to housing-specific intervention” as being of particular concern, but holds out the possibility that a greater emphasis on the value of community and inclusion might strengthen political commitment to affordable housing.

Sean McNelis declines to engage with the substance of my article, leaving it to others to comment on the “the adequacy of [my] explanation of Kemeny’s writings and their development, in particular the dynamic of the relationship between housing systems and welfare systems” (McNelis Citation2020, this issue). Rather, his core point is that the focus on tenure should not be taken as being representative of the housing system as a whole. Tenure is but one “technology” and others (building materials, land assembly, construction, finance) “are as important, if not more important than tenure.” “A housing system,” he notes, “is not simply the processes that bring about the tenure structure.” He asserts that “a regime [is] an aggregate of technological, economic, political and cultural processes, [so] a change in any one of these can bring about change in the housing system.” His (tautological?) conclusion is that, “the dominant ideology will change as it seeks to legitimate changes or other processes.” Since he provides no examples, even hypothetical ones, it is not clear what insights might have been made.

3. Substantive Points

A number of substantive points raised in the commentaries deserve explicit consideration.

3.1. Housing Tenure and Housing Systems

Kemeny used his studies of what he initially termed “rental strategies” to identify “housing regimes”, and I, in turn, referred to the unitary/integrated/dualist markets as “housing systems”. However, it would be perverse to suggest that either of us were maintaining that tenure is the only part of a housing system. Housing tenure is, of course, “only” one part of the housing system, which elsewhere I defined as “the way in which housing policies inter-act with public and private institutions” (Stephens Citation2011, 347). But tenure is a very important part of it, and its study can be illuminating of the system as a whole, provided that it is treated in what I have called a “system embedded” way (ibid.). This means that we need to go beyond narrow categorization (owner-occupation, social rented, etc.) and capture its “contingent” qualities, and understand its jurisdiction-specific legal basis, its financial qualities (e.g. its liquidity as an asset), and its cultural symbolism (e.g. cultures of home-ownership) (ibid.).

To understand how tenure is created requires an understanding of the full range of institutions in the housing system, so that “[i]n substantive terms – that is in defining social relations of occupancy and ownership – tenure can be important and should be expected to have certain social and political effects.” (Barlow and Duncan Citation1988, 229). The effects that most concern me are distributional ones (and I shall return to these later). I readily concede that an interest in other effects might lead scholars to place greater emphasis on other institutions – particularly those located more firmly in the sphere of production rather than consumption – but I would reject any suggestion that Kemeny’s work, or my critique and development of it, is a narrow study of tenure and unrepresentative of housing systems or their change.

3.2. Welfare Regimes and Other Frameworks

Housing scholars have tended to gravitate towards explanatory frameworks derived from, or associated with, welfare regimes. Matznetter suggested that these might be combined with frameworks, such as varieties of capitalism, that seek to reflect modes of capitalist organization. My article makes it clear that housing systems are embedded in wider social and economic structures, and I begin each case study with a contextual section that does precisely that – for example, outlining the Rehn-Meidner model in Sweden and the application of ordo-liberalism in Germany, and the subsequent winding down of both models in response to economic failure or underperformance.

There is a tendency in housing studies to equate welfare regimes with welfare states, hence the almost ubiquitous nod in the direction of Torgersen’s (Citation1987) “wobbly pillar”. I place great emphasis on the organization of labour markets as well as the role of taxation and social security, since these determine patterns of income distribution and poverty. I treat these as being of vital importance for the operation of cost or social rental sectors as they determine? the “boundaries of possibilities” concerning the (predominant) function that social renting plays: “wider affordability”, “safety net” or (in countries such as the US) “ambulance service”. So I agree with Matznetter that the mode of capitalist organization is important, and go further in suggesting that it needs to be extended beyond micro-economic institutions such as labour markets to include frameworks of macro-economic policy. I highlight the importance of Quantitative Easing adopted by central banks in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis in placing upward pressure on house prices and return to its further evolution in response to the COVID-19 pandemic below.

3.3. Other Countries

I agree with the three commentators who suggest that the consideration of other (unitary) countries might shed further light on housing system change. Whilst there is clearly not space for a detailed consideration here, I present a brief review of Austria, Denmark and the Netherlands.

3.3.1. Wider Welfare Regimes and the “Boundaries of Possibility”

In my explanation of housing market change, I place emphasis on the way in which economic crises or underperformance prompted UK, Swedish and German governments to reform their labour markets and social security systems. In particular, in the UK and Sweden this resulted in a rise in poverty with a resultant narrowing of the “boundaries of possibility” for the role of the social and cost-rental sector.

Extending the analysis to include Austria, Denmark and the Netherlands, as commentators suggest, would require a detailed examination of their “wider welfare regimes”, or mode of capitalist organization, if you prefer.

Here, let us take a short cut to the levels of poverty – shorthand for the distributional outcomes of these contextual modes of capitalist organization. extends a table from my article to include the three additional countries suggested by the commentators. Indeed, it is interesting that poverty after social transfers is lower in these countries than in the ones included in my article. In all three, and especially in Denmark and the Netherlands, the poverty rate is lower than in the countries included in my article. This would suggest a somewhat more favourable context for the operation of social markets in the rental sector. However, despite the more favourable distributional context in these additional countries compared with the case study countries in my paper, shifts towards targeting can be detected. Elsinga (Citation2020, this issue) notes the shift towards targeting and Mundt notes that in Austria’s municipal rented sector, “new allocations are more strictly targeted at households in acute need of social housing and at vulnerable groups” (Mundt Citation2018, 15).

Table 1. Poverty (% individuals) 2017

3.3.2. Maturation and Subsidy

A pivotal part of Kemeny’s thesis is the response that governments make when the cost rental sector matures, i.e. begins to generate surpluses. He posits that even if subsidy is withdrawn, in unitary systems surpluses may be sufficient to finance the renovation of existing and building of new stock. The decision regarding the extraction or retention of surpluses is, as Elsinga observes, a political decision. There is no disagreement here: Kemeny treats this explicitly as an “historic juncture”, as do I. Whether surpluses are sufficient to maintain and reproduce the cost rental sector without subsidy is an empirical question. In each of my case study countries surpluses were extracted or lost (Norris usefully notes the “inbuilt ‘self-destruct mechanism’” in Germany), and subsidy much reduced or withdrawn. Is this the case elsewhere?

Elsinga (Citation2020, this issue) highlights the case of the Netherlands which “demonstrates that maturation was able to compensate for the loss of subsidies.” However, the Dutch government approached the “historic juncture” in a rather different way in the mid-1990s when it, in effect, wrote off housing association debt whilst ending future general supply-side subsidies through he “grossing and balancing” exercise. So the loss of subsidies was predicated on a massive one-off subsidy that laid the foundations of the “over mature” system. More recently, surpluses are being extracted through the landlord tax, whilst the role of the sector is becoming more targeted as a matter of policy choice.

In Denmark, the Landsbyggefonden (LBF) was established in the late 1960s to equalize rents, but became a means to retain the autonomy of the housing association sector, and is often seen as the institutionalization of a “revolving door” mechanism for recycling rental surpluses. New development in Denmark’s housing association sector enjoyed both capital and revenue subsidy as well as a tenants’ contribution. However, when, in the early 2000s, the government chose to withdraw subsidy, the fund was rapidly depleted, until subsidy was restored. One analysis concluded “In principle, the Danish system offers a mechanism for ‘revolving door finance. However, the fund intended for regeneration was effectively run down in the 2000s to compensate for reductions in government subsidy for new build.” (Gibb, Maclennan, and Stephens Citation2013, 36). Meanwhile, Austria’s limited profit rental sector exhibits “a revolving-fund component: nowadays (in many regions), repaid loans can be used to finance new construction and therefore decrease the financial burden on regional budgets” (Mundt Citation2018, 14).

3.3.3. Integrated Markets?

A key element in the development of Kemeny’s theory from one concerning rental markets to one meriting the term “housing regime” is the ability of unitary rental markets to compete with home-ownership. In my article, we saw that whilst Germany’s rental sector seemed to have continued to compete with home-ownership, but this was not so in Sweden.

shows that in Austria, as in Germany, renting remains the largest (if not majority) tenure. The other side of the coin, is that mortgaged ownership in Austria, along with Germany is the lowest of the six countries. The Netherlands emerges as the country with the highest rate of mortgaged ownership, and in Denmark it is the largest (but not majority) tenure. (The favourable tax treatment of mortgage interest in the Netherlands is often cited as a reason for the prevalence of mortgage debt.) In Denmark some 16.9 per cent of people living in poverty also live in a household with a mortgage – a figure almost identical to Sweden and the UK (Eurostat, Income and Living Conditions, indicator ilc_lvho02). This rises to almost one-quarter (23.6%) in the Netherlands. These statistics are consistent with a breakdown in integrated housing markets in Denmark and the Netherlands, and their continuance in Austria.

Table 2. Tenure (% individuals), 2017

3.4. Financial Regimes and “Really Big Finance”

Norris makes the interesting suggestion that financial regimes might be added to the framework. These might provide an alternative or complementary explanation for levels of home-ownership. Blackwell and Kohl (Citation2018) have argued that since mortgage bond-based finance systems had to compete with other customers, economies of scale were required in housebuilding; this resulting in a preponderance of multi-family dwellings more suited to renting. In contrast, deposit-based systems, often protected from competition, were able to support retail customers building at the lower densities that allowed for houses to be constructed, a building form more suited to ownership. This thesis is worth exploring further, although it would not explain why, in the collapse of specialist retail circuits and the aftermath of deregulation, wholesale finance flooded into mortgage markets once dominated by depositories, yet houses for home-ownership continued to be built. Where such an examination would be useful, is in establishing whether, nearly 30 years after the establishment of the European Single Market (Stephens Citation2000) the continued low levels of mortgaged ownership in Austria and Germany are attributable primarily to the lack of demand (as I posit) or to supply-side restrictions.

The emergence and evolution of unconventional monetary policy is arguably of greater significance to contemporary housing markets. In my article, I noted the role that quantitative easing adopted by central banks in response to the Global Financial Crisis, along with ultra-low (even negative) interest rates, was likely to have been a cause of rising house prices in metropolitan markets over the past decade. The practice, which involves bond purchases by central banks which frees up banks’ balance sheets for further lending, is especially controversial in Germany where it offends the ordo-liberal principles that underpinned the Bundesbank, and subsequently the European Central Bank and Euro as originally conceived. The German constitutional court ruled against the ECB’s QE programme in May 2020 on the ground that it had strayed from monetary into “economic” policy – leading one commentator to refer to the distinction as “an ordoliberal fantasy world” (Tooze Citation2020). The ECB’s most recent iteration of QE, the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) has strayed further into fiscal policy by focusing on the purchase of government bonds and dropping the “capital key” – the convention by which bonds are purchased in proportion to an economy’s size (Arnold Citation2020). The PEPP, and parallel initiatives by other central banks, marks an intensification of post-GFC actions, and is part of what I shall call “really big finance” that is likely to shape housing systems over the next decade.

3.5. In Search of Appropriate Scale: National, Regional or Local?

Citing Hoekstra (Citation2020), Matznetter (Citation2020, this issue) suggests that, “regional to local housing markets and policies are becoming the appropriate scale for comparative research.” In my article on comparative methods (Stephens Citation2011) I defended the continued importance of the nation state, especially for policy-relevant research on four the grounds. First, nations are still resource rich compared to regional, local or indeed supranational entities. Second, the path dependent importance of past national housing policies and programmes remains even where these no longer exist or have been scaled back. Third, national level housing system institutions such as the mortgage finance and legal systems are clearly important. Finally, the labour market, taxation and social security institutions that make up the wider welfare regime are of vital contextual importance are still largely set and resourced nationally (Stephens Citation2011). A decade later, these reasons continue to be persuasive, although I do agree that regional and local sub-systems can also be significant. The importance of political devolution to the UK’s smaller nations is a case in point (although these are nations not regions), and I have argued that Scotland’s social rented sector has moved more firmly into the “safety net” role when England’s was shifting towards an “ambulance service” (Stephens Citation2019). But since the parameters of the “wider welfare regime” are still predominantly set by the UK government, the “boundaries of possibility” are limited. More broadly, a feature of the post-GFC world has been the boom in house prices in key metropolitan markets that seems to have driven differences within countries, even where formal policy and institutions are still set nationally. Sub-national analysis can complement the national, and may sometimes be the appropriate scale of analysis in its own right, but Matznetter’s view that it is “becoming the appropriate scale for comparative research” (emphasis added) is not one I share.

4. Conclusions

I have structured my responses to the commentators’ comments so as to permit some development of the conclusions to my article. David Clapham “wholeheartedly agrees” with my conclusion that middle-range theories need to be more sensitive to higher forces of convergence and to institutional detail, and suggests that the approach outlined in his book represents a way of doing this. He envisages this as being a “holistic analysis” which takes “elements from a spectrum of theories including welfare regimes, path dependence and financialisation, without being based on one or the other.” (Clapham Citation2020, this issue) I do not seek disagreement for its own sake, and indeed there is much agreement between us. However, I regard financialisation as a process, path dependence as a tendency, and neither to be a theory. Moreover, whilst Clapham is absolutely right to emphasize the importance of a range of factors in shaping housing systems, this pick-and-mix approach to theory does not seem likely to be very coherent in the sense of establishing an explanatory (i.e. theoretical) framework.

I envisage a refinement of the housing-welfare regime approach outlined in the conclusions to my article as follows. Tentatively I refer to this as a typology of a multi-layered housing regimes framework and this prototype is illustrated in .

First, the institutions of the housing system are by their nature located in the middle-range. They are created by path dependent ideologies mediated through power structures, and are supplemented by contemporary policy and behaviour. Whereas Kemeny treated housing as being a unified “sector regime”, we may think of it as being made up of several sub-sector regimes, or spheres. Broadly, these are the sphere of production (or housing supply) and the sphere of consumption (mediated through tenure). The sphere of exchange (housing finance) plays a role both in the sphere of production and consumption. These housing spheres continue to inter-act with my notion of the “wider welfare regime”: the institutions of the labour market, taxation and social security which have distinctive distributional tendencies and set the “boundaries of possibility” of the cost/social rented sector.

Sitting above this are the macro-level drivers, including macro-economic policy in which “really big finance” arising from central bank behaviour is likely to be of key importance. The enduring importance of globalization remains at this level.

Meanwhile, the way the macro-level and middle-range institutions interact will depend on the regional and metropolitan markets in which they operate. There may be variation in institutional arrangement, but market pressures may be the most important driver.

Whether a single ideology is capable of giving coherence to this is moot. Given the different levels of institution design, and the legacy of past ideologies, we must allow for different – even contradictory – ideologies to co-exist as causes of sector regimes. If an overarching characterization can be identified, it may have to be post hoc. The world is more complicated than it used to be.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arnold, M. 2020. “ECB Ponders Pandemic Firepower Limits.” Financial Times Brussels Briefing, June 4.

- Barlow, J., and S. Duncan. 1988. “The Use and Abuse of Housing Tenure.” Housing Studies 3 (4): 219–231. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02673038808720632.

- Blackwell, T., and S. Kohl. 2018. “Urban heritages: How history and housing finance matter to housing form and homeownership rates.” Urban Studies, 55 (16), 3669–3688. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098018757414.

- Blackwell, T., and S. Kohl. 2019. “Historicizing housing typologies: beyond welfare state regimes and varieties of residential capitalism.” Housing Studies, 34 (2), 298–318. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2018.1487037.

- Clapham, D. 2019. Remaking Housing Policy: An international study. Abingdon and New York: Routledge.

- Clapham, D. 2020. “The Demise of the Welfare Regimes Approach? A Response to Stephens.” Housing Theory and Society. this issue.

- Elsinga, M. 2020. “About Housing Systems and Underlying Ideologies.” Housing Theory and Society. this issue.

- Gibb, K., D. Maclennan, and M. Stephens. 2013. Innovative Financing of Affordable Housing: International and UK Perspectives. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Hegedüs, J. 2020. this issue.

- Hoekstra, J. 2020. “Comparing Local Instead of National Housing Regimes? Towards International Comparative Housing Research 2.0.” Critical Housing Analysis 7 (1): 74–85. doi:https://doi.org/10.13060/23362839.2020.7.1.505.

- Matznetter, W. 2020. this issue.

- McNelis, S. 2020. this issue.

- Mundt, A. 2018. “Privileged but Challenged: The State of Social Housing in Austria in 2018.” Critical Housing Analysis 5 (1): 12–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.13060/23362839.2018.5.1.408.

- Norris, M. 2020. this issue.

- Stephens, M. 2000. “Convergence in European Mortgage Systems before and after EMU.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 15 (1): 29–52. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010194725136.

- Stephens, M. 2011. “Comparative Housing Research: A “System-embedded” Approach.” International Journal of Housing Policy 11 (4): 337–355. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14616718.2011.626598.

- Stephens, M. 2019. “Social Rented Housing in the (Dis)united Kingdom: Can Different Social Housing Regime Types Exist within the Same Nation State?” Urban Research & Practice 12 (1): 38–60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2017.1381760.

- Stephens, M. 2020. “A Review of “Remaking Housing Policy: An International Study”, by David Clapham.” International Journal of Housing Policy 20 (2): 302–304. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2020.1716290.

- Stephens, M., N. Burns, and L. MacKay. 2003. “The Limits of Housing Reform: British Social Rented Housing in a European Context.” Urban Studies 40 (4): 767–789. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098032000065290.

- Stephens, M., M. Lux, and P. Sunega. 2015. “Post-Socialist Housing Systems in Europe: Housing Welfare Regimes by Default?” Housing Studies, 30 (8): 1210–1234, doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2015.1013090.

- Tooze, A. 2020. “The Death of the Central Bank Myth.” Foreign Policy, May 13.

- Torgersen, U. 1987. “Housing: The Wobbly Pillar under the Welfare State, Scandinavian Housing and Planning Research.” . 4 (sup 1): 116–126. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02815737.1987.10801428

- Whitehead, C. 2020. this issue.