ABSTRACT

To a large extent, established formal participation schemes fail to deliver on their promise of transferring substantial power to tenants, while self-organized housing remains a niche for those who have a strong inclination and ample resources. Given the rise of renting in Europe, and the intensifying housing crisis, increasing tenants’ ontological security by allowing them meaningful influence is urgent and important. Self-management, where tenants take over practical tasks from their housing provider, has the potential to expand the immediate influence of tenants over their direct environment in a more accessible manner than self-organization or formal participation. Yet, knowledge about such self-managed housing is limited and analyses are few. In this article, we present findings from a qualitative case-study of a Dutch project that is managed by its tenants. We conclude that self-management can have added value, but unless it is integrated in formal participation structures, its impact will be limited.

1 Introduction

Since the introduction of the new housing law in 2015, Dutch housing corporations are adjusting to their new roles. Specifically, rather than engaging in a wide range of activities for a broad audience traditionally including middle income groups, they are now to focus on housing low-income or otherwise vulnerable groups, that cannot fend for themselves on the free market. A desire to narrow the distance between themselves and their tenants is also part of the new ambitions. This ties in with broader societal trends of giving citizens more of a say about their direct environment. There is, however, little experience with significantly increasing tenants’ influence by letting them manage their housing themselves, especially in the Netherlands. Academic articles with a robust theoretical underpinning on this topic are scant and practitioners are searching for ways to implement this new strategy. Furthermore, in several European countries, since the 2008 global financial crisis, more households rent, and this number is likely to increase (Hulse, Morris, and Pawson Citation2019; Huisman and Mulder Citation2022). Yet, after decades of experiments with tenant participation, lack of influence over their housing is one of the main reasons for households to prefer to own their home rather than to rent (Foye, Clapham, and Gabrieli Citation2018). In itself, improving tenants’ influence is important because it increases their ontological security (Huisman Citation2020).

Hence, in this paper, we examine self-management; where tenants take over practical tasks from their housing provider, and ask in how far and in what way it increases tenants’ power. This translates into the following research question: how can we understand self-management and what could be its added value for tenants’ influence?

We answer this question by means of a case study of a project, the Startblok Riekerhaven in Amsterdam, where the tenants, 565 young adults, take over a large part of the tasks usually executed by the home-owner. In the remainder of this paper, we first zoom out to explore the distinct ideas of self-organizing and self-managing citizens and connect these to formal participation in housing. By fleshing out the conceptual differences between these forms of tenant engagement, the article contributes to the formation of robuster theories. We proceed with providing some context on Dutch housing and tenants’ formal participation rights, and clarify differences with self-management schemes elsewhere in Europe. Then we further justify why we selected this particular case and how we carried out the research. After describing the case, we present our main findings. Self-management as we observed it has added value compared to standard renting situations, because it leads to greater involvement of tenants. Taking over practical tasks from the housing provider can expand the immediate influence of residents over their direct environment in an accessible manner. However, the impact is limited, due to the absence of an embedding in formal participation structures. We conclude that self-management provides a new mode of involving residents in their housing, whose relevance depends on its integration in formal participation structures.

2 Theoretical Framework

Self-organization, Self-management and Tenant Participation in Housing

The popularity of the idea of citizen participation in urban policy has proven to be resilient over time. Currently, this popularity expresses itself in the idea of self-organization. Whereas the state has often come to be seen as failed and the market as an unreliable partner, bottom-up action has become a popular policy model, and government is to be facilitator of this process (Uitermark Citation2015). Before looking at the trend of allowing citizens more influence specifically in the domain of housing, we first explore this development more broadly. When it comes to citizens taking matters into their own hands, self-organization and self-management are two sociological concepts that in the literature are often used interchangeably. We first define self-organization. At the geographical level of the city, and linked to complexity theory, self-organization refers to unintentional and unconscious processes of urban development; the “spontaneous emergence of urban structures on a particular scale out of the uncoordinated interactions between initiatives on a lower level” (Rauws Citation2016:339). Uitermark (Citation2015) warns against such depicting of cities as organically evolving networks, since it naturalizes existing political and economic structures that constrict what is possible. However, we are interested in more conscious and intentional forms of citizen action, where people share a common goal, and pursue this together themselves. According to Rauws, such self-organization resembles self-governance; when “citizens deliberately organise themselves in order to realise a collective ambition” (2016:339). Uitermark focuses on the absence of the state, when he defines such self-organization as when “people can coordinate and cooperate without delegating power to a central authority”, or more colloquially “collective action by citizens that is not directed by the government” (2015:2301–2302, 2304). Ideas of co-creation (during strategic planning) and co-production (during implantation) (Brandsen and Honingh Citation2018) in contrast, emphasize the synergy leading to better outcomes that under certain conditions can come in existence when citizens and governments or companies work together to create goods or services (Ostrom Citation1996).

The idea of self-management originates from labour theory and practice. The first instances were part of the historical cooperative movement, with businesses led by the workers themselves (Széll, Blyton, and Cornforth Citation1989). With the rise of the neoliberal ideology and the economic recessions of the 1980s (Palley Citation2005) the idea of self-managing teams became influential in organizational studies, since they promised to increase productivity at a low cost, while simultaneously improving employee work satisfaction (Manz Citation1992). Rather than being managed at close hand by a supervisor, self-managing teams, usually consisting of 5–15 people, are given a certain target or goal. Together, they can decide on the best way to reach this goal, and act on this. Members of self-managing teams enjoy more personal freedom in how to go about their work than traditionally managed employees.

Manz proposes a move from self-managing teams to self-leading teams, where employees also get to decide on which goal to pursue, and for what reason. This means that: “employees are empowered to influence strategic issues concerning what they do and why, in addition to the issue of how they do their work.” (Manz Citation1992:1119, emphasis in original). This can be viewed as expanding self-management towards self-organization. The main difference between the two concepts is that self-organized citizens unite upon a common goal that they agree upon amongst themselves, whereas self-managing employees are a part of a broader organization, and they only have limited control over what goals they pursue. Self-management seems to conjure up a promise of a larger transfer of power than it delivers in practice. Hence, the resonance of the claim that “‘employee self-management’ in many ways is often more of an illusion or myth than a reality” (Manz Citation1992:1119). This echoes Sherry Arnstein’s seminal work on citizen participation (Citation1969). For her, unless there is some real redistribution of power between those who traditionally have little, and those who have most, giving citizens some influence remains an empty ritual. From a Foucauldian point of view, such rituals can be seen as forms as governmentality. Rather than managing people through a hierarchical and open exertion of power, self-managing teams can function as vehicles for governing people through mutual internalization of values and norms.

Zooming in on the domain of housing, we observe that studies on collaborative housing (“collective self-organised and self-managed housing”, Lang, Carriou, and Czischke Citation2020), usually examine cases of self-organized citizens: when residents take the initiative to join forces to develop or buy their own housing as a group.Footnote1 Such initiatives constitute co-creation when they cooperate with local government and private companies (Brandsen and Honingh Citation2018; Czischke Citation2018). In this article, we focus on self-management, when residents become involved in the management of their housing, while the ownership remains with the landlord. When tenants undertake these tasks without remuneration, self-management can be viewed as coproduction, and this sometimes also occurs at lower levels of housing cooperatives. As in labour, self-management can be introduced to cut costs, by increasing efficiency, which savings can be used to lower rents and create more affordable housing stock (for a Danish example, see Jensen and Stensgaard Citation2017). Having more of a say about one’s home can also increase ontological security and strengthen social connections. Self-management means residents take over specific tasks from the landlord. These tasks can involve managing as governing; deciding and supervising, for instance, hiring repair people or cleaners (in the United Kingdom, this definition prevails). But self-managing tenants can also execute such tasks themselves, for instance carrying out repairs or cleaning common spaces (in the Netherlands, this definition prevails). However, as with self-managing teams of employees, in either case, self-managing tenants only obtain limited influence on strategic issues; most power stays with the landlord.

As with labour, top-down initiated self-management of tenants can also be viewed as a new way to discipline and responsibilise tenants (Costarelli, Kleinhans, and Mugnano Citation2020; Scheller and Thörn Citation2018). While elements of governmentality can indeed be traced in such housing, Huisman (Citation2019) argues, on the other hand, that there might also be advantages to such an organizational form. Self-Organized housing demands a large input in terms of time and energy (Bresson and Labit Citation2020), that people might not have readily available, or they might choose to spend their time in a different way. Self-managed housing is less demanding in this respect, making it more accessible; “the threshold for participating is much lower than in more autonomous self-organised projects, making it easier for tenants with other obligations or inclinations to take part” (Huisman Citation2019), while still offering more influence than more traditional forms of housing. Indeed, it is precisely because self-management presents an alternative halfway between the two extremes of tenants as passive consumers and autonomous self-organized citizens, that it is such an interesting organizational form. But this position also creates tensions, since self-management consists of a transfer of some, but not all power from the landlord to the tenants.

Similar issues occur with the related but distinct concept of formal tenant participation, here understood as increasing the democratic influence tenants have over decisions pertaining to their housing through rules and regulations (Kruythoff Citation2008). The substance of what tenants exactly do or do not get to decide about, is not often put centre-stage in the literature. However, how meaningful taking part in decision making processes is for tenants, depends a great deal on the salience of the issues under discussion, as well as the actual influence tenants achieve (Huisman Citation2014). Ontological security in housing, the feeling of safety that originates from the knowledge that your home is a long-term stable, affordable, good quality and secure place, is at the core of tenants’ interests (Huisman Citation2020). Rent levels and rent increases, termination of contracts, and plans for demolition, renovation or sale of the housing are important points that impact upon ontological security. Furthermore, the state of maintenance and of the social environment influence tenants’ experience of their housing. Whether tenants can only respond to plans made by landlords, or whether they can also actively come up with proposals is another relevant factor. For tenant participation to have a meaningful effect upon their ontological security, beyond giving advice, decision making power needs to be transferred to tenants.

However, established formal participation schemes fail to a large extent to deliver on their promise of transferring substantial power to tenants. There are several reasons for this, namely: it is difficult for tenants to join forces to defend their joint interests, tenants lack resources such as time and knowledge and the set-up of participation schemes (“the rules of the game”). To start with, the unrealistic idea of spontaneously, effectively and efficiently self-mobilizing and self-organizing citizens appears strongly in theories about tenant participation (Bengtsson Citation2000). In this context, it is important to consider Olson’s problem of collective action (Citation1965): even if it is in the interest of all individuals that share a certain interest to join forces to secure that joint interest, it does not follow that they will actually do so. In fact, it does follow, assuming all these individuals act rationally, that although it would be in all of their interests if they would join forces to secure their joint interest, they will not.Footnote2 Beyond this serious obstacle, tenants often lack resources (Cronberg Citation1986). Tenants lack time, while engaging in these processes is often very time consuming. Tenants have to engage in their free time, which they might not have or choose to spent it in a different way. Tenants also lack knowledge, since professional managers are trained in housing issues, and tenants are not. The professional support that is sometimes offered to tenants in formal participation only mitigates this problem slightly, since professionals often become institutionalized (Uitermark Citation2009). In itself, these obstacles limit the power of tenants. On top of this, the rules of the game are usually determined by the housing provider, in terms of setting the agenda. What is up for discussion and what not is usually decided by the housing provider, who portray certain issues as unavoidable, i.e. there is no alternative. In this context, formal participation can function as a technique of government (Huisman Citation2014).

Indeed, given that the interests of the landlord and the tenants are not necessarily aligned, meaningful transfers of power are thorny. For instance, a housing provider might be concerned with economies of scale, planning to maintain several of their houses at the same time, at some moment further in the future, to save money. Tenants want the maintenance of their homes to take place sooner rather than later. Housing providers also exist in a political context, which changing goals reflect themselves in their policies; in the following section we elaborate upon the Dutch political context. Finally, there exist several instances where “tenant participation” has been used for political ends. For instance, participation has been used to legitimize state-led gentrification policies that resulted in displacement of tenants (Huisman Citation2014).

To conclude this section, in all three forms of tenant engagement described above, residents are involved in different constellations at different scales. Self-Organized housing mostly attracts like-minded people with ample resources. Self-management can include all tenants at the most basic level, for instance in making them responsible for and giving them control over cleaning common entrance halls and stair cases. Formal participation arrangements follow the format of representative democracy. In summary, whereas self-organization encompasses citizens initiating and developing a project by themselves for themselves, and self-management transfers part of the responsibility for and control over practical tasks to tenants, formal tenant participation seeks to extend the democratic control of tenants over the governing of their housing. As a result, formal tenant participation involves tenants meeting and deliberating, among themselves as well as with housing providers’ staff. Self-managing tenants take over work, such as rent administration. However, as in labour, self-management increases the decision-making power of tenants, specifically at the micro-level. Maintenance done by tenants, allows them more influence on how they execute this task. Also, involvement in management necessitates a continuous line of communication with the housing provider.

Situating Tenant Participation in the Netherlands

To clarify these issues, we look at formal tenant participation in the Netherlands and explore tenant self-management in the United Kingdom, which in a different form has been established there for over forty years (Cairncross et al. Citation2002). To start with the Netherlands, after decades of the promotion of home-ownership and the privatization of rental housing, housing corporations, until the mid-1990s democratic associations providing the majority of all housing, have become not-for-profit foundations restricted to providing housing for those who are not (yet) capable of fending for themselves on the market. Following the loosening of government ties in the mid-1990s, housing corporations initially focused on selling off a substantial amount of their housing stock in order to push/seduce the middle classes out of social housing. After the economic crash of 2008, and under pressure of the outcomes of a 2012 Parliamentary inquiry into the excesses of the adaptation of business models (Van Vliet et al. Citation2014), including speculations with derivatives resulting in the bankruptcy of a major housing corporation (Aalbers, van Loon, and Fernandez Citation2017) housing corporations were tasked with a policy of ring fencing the social housing stock for only the poorest. This results in gradual residualisation, the process where regulated housing increasingly becomes occupied solely by the most disadvantaged households.

This most recent reformulation of their core task is anchored in the Housing Law of 2015, which also introduced temporary leases as well as a larger role for tenant participation. Currently, 28% of homes in the Netherlands are owned by housing corporations, 12% by private landlords and 60% are owner-occupied (Lijzenga et al. Citation2019). While time-limited leases are strongly on the rise (Huisman & Mulder Citation2020), the majority of leases from housing corporations still remains permanent.Footnote3 The emphasis on new forms of tenant participation derives from the Dutch concept of the “participation society”, aptly dubbed “more society for less” (Hurenkamp Citation2020), contemporary to the British 2010 government’s “Big Society” ideology that “ostensibly, [.] was aimed at devolving power from the state. Specifically, communities could be more involved in the organisation and delivery of previously public services”, alongside budget cuts (Dowling and Harvie Citation2014). However, the desire from housing corporations to narrow the distance between them and their tenants, was also influenced by the critique resulting from the Parliamentary inquiry mentioned above, that housing corporations lost touch with their tenants.

Formal participation rights in the Netherlands exist at different levels. At the level of the home, tenants’ participation rights concern landlords’ plans for demolition or retrofitting beyond normal maintenance. If the tenant does not find the landlord’s proposal reasonable, for instance in terms of rehousing or rent increases, the landlord needs to resort to the courts who decide about the reasonableness of the proposal. At the level of the block, when several homes adjacent to each other are owned by the same housing corporation, tenants can unite in a resident committee, and obtain formal rights concerning the governance of the block, including the right to be informed about relevant topics such as maintenance and future plans, the right to meet regularly with the landlord and the right to advise. On the municipal level, tenant organizations have the right to be informed and advise about policies and plans of the housing corporation, such as rent prices and allocation policies and plans for building, demolishing, buying or selling of stock. Municipal tenant organizations advise during periodic negotiations between housing corporations and municipalities about the housing policy for the coming years, and can put forward a minority of advisory board members. Local tenant organizations often join the national federation (Woonbond).

As argued in the theoretical framework, in practice, however, these rights are heavily constrained. Take the case of the state-led gentrification plans for the Tweebos neighbourhood in Rotterdam, involving demolition and forced displacement of many disadvantaged tenants. In April 2021, United Nations special rapporteurs drew attention to possible violation of human rights. They noted that formal participation rights had been bypassed: “Residents have not been involved in the planning and decision making for renewal plans and demolitions in their neighbourhoods [… while under] the Tenants and Landlords (Consultation) Act, landlords are required to inform tenants and residents as soon as possible of any plans involving policy or management changes, including any demolition and renovation plans, in order to enable them to obtain clarifications and engage in consultation.” (Rajagopal et al. Citation2021:4). Akin to for instance Sweden (Polanska and Richard Citation2021), the national tenant federation acts as a bureaucratic service organization rather than an active political body. While power transfers to tenants are thus in practice limited and heavily circumscribed, the existence in the Dutch system of a rights-based structure for tenant participation does create some political space for deliberation and contestation.

In the United Kingdom a similar picture emerges as in the Netherlands, of formal participation rights that can in theory strongly empower tenants, but in practice show very mixed outcomes. On the one hand, successive national governments in England purposely tried to weaken the power of the municipalities by transferring stock to housing associations (Bradley Citation2008), and using tenant participation through the Tenant Choice scheme to attempt to force this, with limited success. On the other hand, many local authorities were actively involved in the large scale voluntary transfer (LSVT) scheme that was implemented over twenty years. The transfer to housing associations sometimes resulted in tenant empowerment and improved housing conditions (Pawson and Mullins Citation2010). The right for local authorities in the United Kingdom to “delegate budgets and responsibility for housing management and maintenance to tenant management organizations” exists since the mid-1970s (Cairncross et al. Citation2002:15). The resulting Tenant Management Organizations (TMOs) occur at a range of scales – from a few, to thousands of houses – and with a variety of legal forms, but with the core idea that a board of tenants acquires significant management and budgetary authority previously held by the owner. Their political role depends heavily on the local context; a TMO can, for example, become a vehicle whereby dissatisfied tenants attempt to counter neglect or mismanagement of rental housing by a municipal landlord; but equally a TMO can be an instrument used by municipalities to strategically distance themselves from housing provision.Footnote4 In any case, tenants involved in TMOs potentially have more power than self-managing tenants in the Netherlands. Specifically, TMOs decide how and when maintenance and operational budgets are spent (e.g. which repair companies to hire), while in the Netherlands the emphasis is on tenants executing certain tasks themselves, with at best indirect influence on management decisions – by providing the landlord with feedback on proposed decisions, for example.

3 Method – Research into Self-management

This study forms part of a broader research project on how Dutch housing corporations and residents’ groups that take up more responsibility for and gain more control over the management of their housing work together. A case study is best suited to answer our research question, since it can deliver in-depth insights into what happens when tenants take over practical tasks from their housing provider. In this way, we can establish what its added value for tenants’ influence could be. We selected the Startblok Riekerhaven as a case because of its innovative set-up of housing together a large number of refugees that recently received asylum and young Dutch adults, while the housing corporation employs self-management to create a sense of community. There are still few examples of tenant self-management on this scale, especially in the Netherlands. A number of similar projects have emerged, several of which are using the current case as a template, so it is important to deepen our understanding of this case.

The research was conducted during 11 months. Our qualitative methodology consisted of participant observation, complemented with semi-structured interviews and interactive workshops. This allowed us to move beyond researching what people say, to observe what actually happens, especially in interaction between tenants and the housing corporation. Participant observation occurred at meetings of tenants in organizational roles, such as their monthly meetings. Additionally, interviews covered 8 tenants in organizational roles (both refugee and Dutch) and 3 representatives of the housing corporation. In the context of the wider research project, an international seminar was held. The seminar focused on two themes, namely “social inclusion” and “collective self-determination”, which emerged from our field work. Next to scientists and practitioners, tenants and professionals from the case participated in the workshops and panel discussions and reflected on the topic from their position. Parallel to this we consulted a range of secondary data, such as the Startblok website, media attention and quantitative survey data describing tenant satisfaction in the project. The primary data was analysed in an iterative manner: insights from observations were used to inform further fieldwork. To protect the privacy of our respondents, we use pseudonyms for their names.

4 Findings- Self-management in Practice: More Influence, but Limited Impact

The Case: Promoting Interaction through Self-management

The Startblok Riekerhaven was developed by De Key in response to the sharp increase in 2015 in the number of refugees being granted asylum in the Netherlands. De Key is one of the six housing corporations in Amsterdam, who provide the majority of housing in the city (AFWC Citation2018). One idea that emerged was to mix young Dutch adults with refugees that had received an asylum status, solving the immediate need for housing of both groups, while enhancing integration (Czischke and Huisman Citation2018). Refugees that receive asylum are mostly young single adults. This category fits well with De Key, who recently changed its mission statement away from general housing provision, to providing solely for starters (young adults) on the housing market (De Key Citation2015). The residents of the Startblok Riekerhaven are 565 young adults within the age range 18–27, with two-thirds of them under 24 years. Half of them are Dutch young adults, the other half refugees who recently obtained a Dutch residence permit. The rents at the Startblok are moderate according to local standards. Reflecting eligibility requirements for social housing in the Netherlands, tenants need to have a low to lower middle income when they sign the lease. This is a youth contract, introduced nationally in 2016, only available to those under 28, that lasts for 5 years.

Startblok refers to starting blocks in Dutch, the idea being that the project provides young adults a head start in life. De Key wants to foster a sense of community between tenants in order to improve social cohesion, life opportunities and well-being. Their rationale for implementing self-management is that it will increase interaction between tenants, stimulating social connections. Notably, cost-savings are not the goal nor the result of the project. The self-management model is at best cost-neutral, but this is regarded as acceptable given its function of promoting interaction. In the case at hand, this is especially pertinent given that half of the tenants are recent refugees. We address the potential beneficial effect of collaborative housing on integration in other papers based on this case-study (Czischke and Huisman Citation2018; Huisman and Czischke Citation2020). Here, we focus on self-management and its potential for enhancing tenants’ influence. It is, however, important to note that both the Dutch and the refugee tenants are self-supporting. The Startblok is not a form of supported housing for those not (yet) capable to live on their own, such as previously homeless young adults. In the Netherlands, adult refugees that have been granted asylum and hence obtained a residence permit are allocated social housing. They are not placed in supported housing, and they never have been. As such the Startblok, which houses young adults, should not be viewed as a replacement or displacement of supported housing structures. Moreover, we argue that the Startblok should not be viewed as an instrument of residualisation, described above as the process where regulated housing increasingly becomes occupied solely by the most disadvantaged households. The tenants of the Startblok have in common that they are all young adults, of which some are still studying and others are already employed, and disadvantaged tenants are not overrepresented. Of course, being forcedly displaced from their country of origin puts the refugee tenants, who also show resilience, at a disadvantage compared with other young adults. However, being granted asylum and obtaining housing, as well as the integration trajectory of language training and coaching towards work that all refugees in the Netherlands receive, offers the refugees opportunities to overcome this disadvantage over time. Furthermore, while the use of five-year temporary contracts is part of a shift from permanent to temporary contracts in the Netherlands, this should not be overstated in the present context. The Startblok consists of physically temporary housing that is additive to, rather than displacing permanently-rented social housing, a result of its origin in the emergency policy response to a large influx of (mainly young and single) refugees following the Syrian refugee crisis of 2015.

The Startblok Self-management Model: Appointed, Reimbursed Tenants in a Hierarchical Structure

In this section, we analyse how the self-management of the Startblok is organized, and how it relates to self-organization and formal tenant participation. During development, De Key put the management of the project out to tender, and selected Socius for this task. This company has developed a model for temporarily transforming large vacant buildings into living spaces for young adults. The model stands out for the cost-effectiveness of the retrofitting, and the focus on self-management. The Startblok’s organizational model was adapted from the Socius model, because of the larger scale of the project and because half of the tenants are recent refugees. Based on our fieldwork, we identify four core elements of the Startblok’s self-management model. The first is a significant transfer of responsibilities for and control over managing the project from the housing corporation to the tenants. The second is proportional monetary compensation for tenants that assume organizational roles. The third is the hierarchical set-up. The fourth is that tenants in organizational roles are not elected but appointed. Furthermore, specific to this project is the consistent even mixing of refugee and Dutch tenants at every level of the project.

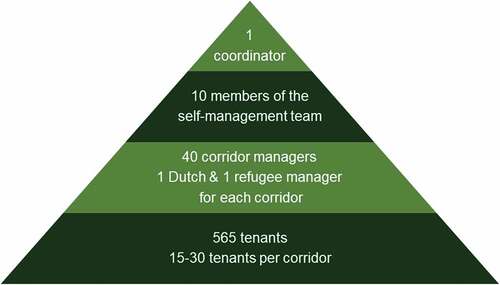

These traits can be found in the organizational model depicted in . For a more detailed description of how the Startblok is organized, we refer to Czischke and Huisman (Citation2018). As mentioned above, the usual idea in self-organization and citizen/ tenant participation is that of a volunteer organization with a broad, flat base that spontaneously and democratically organizes. In contrast, the Startblok model consists of layers in a pyramidal hierarchical form, with increasing responsibility, control and monetary compensation at each level. Each layer mainly engages with the layer above and below them. At the bottom of the pyramid, we see groups of tenants living together across corridors; the units the housing is divided into. Each corridor houses between 15–30 tenants, half of them Dutch and half of them refugee, as evenly mixed as feasible. On the corridors each room has its own kitchen and bathroom, and is thus in principle independent, but there is also a shared common room and kitchen. The next layer is that of the corridor managers. They receive a compensation of 50 euros per month for executing certain practical tasks. The corridor managers act in pairs, one refugee and one Dutch, and ensure that the shared spaces stay tidy. They are also the persons to turn to, for instance when issues between tenants on their corridor arise. The tenants on their corridor inform them about their experiences, which the corridor managers in turn share with the layer above them; the self-management team. Also, if the corridor managers feel a certain situation is too hard for them to handle, they will transfer this upwards. In this way, the self-management team becomes knowledgeable about the issues experienced by the tenants without speaking to all tenants themselves. The team consist of 10 people mixed evenly again between refugees and Dutch tenants. They are employed for approximately 12 hours per week by the housing corporation and coordinate the corridor managers. Vacancies for corridor managers are filled through an open application model, whereby a subset of the team decides who is most suitable, for instance in terms of reliability and communication skills. The team is also responsible for rent administration, maintenance, public relations and community work. Only one professional is present at the site: the non-residential project coordinator. Vacancies within the self-management team are filled through an open application model, whereby an ad hoc subcommittee of the team and the project coordinator decides who of the applying tenants is most suitable.

As such, the self-management model constitutes a hybrid model: the tenants that assume organizational roles stay “one of the people”, in the sense that they remain tenants living in the complex (as opposed to living elsewhere) but get partially (monetary) compensated for their time, allowing them to obtain more knowledge. This is akin to the model for municipal councillors in the Netherlands. Councillors are supposed to have a job/ other occupation, and receive a financial compensation (1000 euro per month) for the time (16–20 hours per week) they spend on their council work. Hence, being a councillor is not considered a full-time job in itself, and councillors are not professional politicians, but rather knowledgeable citizens compensated for their time, allowing them a degree of knowledge/ professionalization.

Self-management in Practice: Added Value, but Lack of Formal Participation Structures

We find that self-management as implemented at the Startblok has added value because it strengthens tenants’ influence over day-to-day management of their housing. The obstacles associated with formal participation listed in the theoretical framework are partially removed. Recall that these were the difficulty tenants experience with joining forces to defend their joint interests, tenants lacking resources such as time and knowledge and the set-up of participation schemes (“the rules of the game”). Specifically, lack of time is partially solved because tenants are financially compensated for their time, and by offering different levels of engagement. Similarly, lack of knowledge is partly remedied because of the layered structure combined with the monetary compensation, which allows tenants in organizational roles to gain more knowledge about housing (for instance technical knowledge about maintenance) and to become more knowledgeable about the issues the tenants of the block are experiencing. At the same time, the risk of institutionalization is reduced because they stay tenants, and stay connected through the layered structure. Finally, the self-management imbues them with some power, putting them in a position to become aware that more influence could be possible.

However, the involvement of tenants in formal participation and self-management differs. In formal tenant participation, tenants (at least in theory) obtain influence on substantial decisions about their housing. In self-management, tenants take over practical tasks from their landlords. This brings us to the limitations of self-management as implemented at the Startblok. No formal participation structure was installed to complement the self-management. In theory, the tenants of the Startblok might have the same legal rights as other tenants in the Netherlands in terms of democratic influence. As mentioned above, this includes the right to be informed about rent increases, maintenance and future plans, the right to meet regularly with the landlord and the right to advise. (This is uncertain since youth contracts were only introduced in the Netherlands in 2016, and the right to formal participation of tenants with such contracts has not yet been tested in court.) In any case, the difficulties tenants experience navigating the (political) complexities of participation schemes also hold for the Startblok tenants, making it hard for them to demand a seat at the housing corporation’s table.

The lack of formal participation structures leads to several stumbling blocks, which we identified through our fieldwork. To start with, the project is ambitious; the goal is that the tenants form a community together to improve social cohesion, life opportunities and well-being. Self-management by its very nature indeed promotes interaction, but there exists a lack of clarity about how to go beyond this. The members of the self-management team nor the housing corporation make conscious estimations of how much is feasible and what is a priority. As a result, the team feel pressed for time, since they are trying to achieve all the goals simultaneously, “Our ambitions are not always realistic given what we are able to do” (Megan, self-management team member). This relates directly to the structure of the cooperation. How all involved will work together is not made explicit, nor agreed upon. How decisions are made and how information is shared by the housing corporation remains unclear to the self-management team. Emily: “We are trying to find our way ourselves because there is no clear structure from the housing corporation”.

When we look at the specific actors, De Key took over the role of Socius after two years because they wanted to become more involved in the project and because they wanted to develop expertise in self-management. Furthermore, the self-management does not save money with respect to normal renting, but costs slightly more – due to extra staff costs and the payment of self-managers. However, while thus to some extent committed to self-management, the housing corporation is only slowly adapting to the self-management in the Startblok, as illustrated by the following quotes of employees.

Daniel: ‘For me, the self-management was hard getting used to it. We were used to having certain ideas and that would be the way it would happen.’

Chloe: ‘Not everyone at the housing corporation has woken up yet, [.] for some of my colleagues self-management remains very far away from their daily practice.’

Jack: ‘That the housing corporation really has to get used to self-management I notice all around. I have been working here now for ten years, which actually makes me a newbie because many employees have worked there much longer. So it’s full of people with ideas that are set in stone, who find it rather difficult to think in a different way, and self-management involves a proper change in culture. It is a large organisation so certain things do not move quickly.’

The housing corporation is searching for the right balance between being involved and giving the self-management team autonomy to make and execute their own decisions without losing control.

Daniel: ‘Letting things happen, and well yes, letting the self-managers undertake things themselves [.] We are looking for a way that the self-management team, that they have a certain degree of autonomy themselves, but at the same time, that our internal way we have arranged matters, that it is conform those rules.’

Relatedly, despite the agreement on the goals in general, the housing corporation staff lack clarity about what they want the project concretely to look like, and they identify this by reacting to things they observe and consequently think need changing. Lauren: “During meetings, we will hear from the housing corporation: ‘We do this differently, we do not do it like this, but actually, we are not so certain how we do it and how we are going to do it.’” For instance, some technical tasks that used to be done by the maintenance team, now have to be done by external professionals, since the housing corporation considers it not compliant with safety regulations for tenants to do this themselves, Joshua: “At first, we also used to do maintenance on electrics, but then, the housing corporation told us we were not trained for this and this constituted a safety risk, so we had to stop doing that.”

From the point of view from the self-management team, there is a feeling that, although well-intentioned, the housing corporation remains distant and does not communicate well. A recurring point was that the housing corporation apparently did not yet fully understand (or realize) that the Startblok is a self-organized body with knowledge, experience and opinions – and thus a logical partner to involve in decision-making about the complex. Jessica, from the self-management team, reflects on what could be improved in the relationship with the housing corporation:

‘That the people from the housing corporation, that they look at: what is there already and what can we learn from that? And they do not heed it and they do not need to listen to it completely, but at least listening in itself is, in my opinion, very important. I think this is going a bit better in some areas, but it could be still much improved. Because I think the communication is rather lagging behind, and the wheel is being reinvented rather a lot, while we are here [at the Startblok] very well on track. I think quite many mistakes are being made that could really have been avoided. [.] And they say it very often, that they are going to listen. But then I see little of it in reality, and I think that is a pity.’

Indeed, several interviewees commented that it can be difficult to obtain information from the housing corporation and that some decisions by the housing corporation have a top-down flavour and seem slightly oblivious to the conditions “on the ground” at the Startblok.

Emily about the transfer from Socius to De Key: ‘We were under the impression and they kept us under this impression that the transfer would be discussed with us when it would become relevant. And afterwards we heard that a long time ago decisions were already made, which we were never informed about. Not even about the fact that there would be a meeting or that things would be decided at all, and we only heard months afterwards.’

We furthermore observed that the members of the team, like tenants more generally, find it difficult to articulate and strengthen their negotiating position vis-à-vis the house owner. Among the Dutch young adults, the project tends to attract socially motivated people. Many of the tenants are idealists, but they have not been trained in governance or political organization, and this opens the door to feelings of resignation.

This is also important for the working relationship between the self-management team and the other tenants of the Startblok. Despite having been established only two years ago at the moment the research was done, the internal organization of the Startblok already felt somewhat institutionalized. Sophie: “This is something I hear from people, for instance last week when we were doing job interviews, that people see us a bit as a clique”. This creates a sense of distance between the less involved tenants and the organizers, and this feeling flows both ways. Several self-managers said that they would like to see more active involvement from other tenants. They have experienced first-hand that, although many are willing to undertake small, incidental tasks, few tenants are willing to take on more structural responsibility. This leads to a further centralization of responsibility and control around core organizers, as can be observed in other projects as well.

To summarize, as mentioned above, the housing corporation is only slowly adapting to self-management. The self-management team identifies as their main issue their relationship with the housing corporation. They feel that their cooperation could be improved, if the housing corporation would share more information with them and if they would show more interest in the knowledge and experience of the self-management team. Some members of the team felt overburdened with their responsibilities. They also feel that they could be better connected with the tenants who are not in organizational roles, but struggle to make this a reality. Ultimately these problems stem from the lack of communication, and the lack of the integration of the self-management in formal participation structures which would constitute a transfer of part of the power to tenants.

As described in the theoretical framework, this formal participation should consist of several elements, the right to give advice, the right to consent and the right of initiative. The right to advise would encompass that the housing provider has to inform the tenants about any substantial plans, with an explanation about the reasons and consequences of the intended decision. The tenants then obtain the right to advise on this, and the housing corporation has to motivate what they do with the advice. Such a right to advise would likely improve the transparency that, in their quotes above, Emily and Jessica note to be missing. The right to consent means that for some substantial decisions the tenants need to agree in order for the decisions to be valid; this would prevent the housing association taking quite far-reaching decisions behind closed doors, which (as noted by Emily) are sometimes presented months after the fact to the tenants. In the case of the Startblok, relevant decisions about substantive issues would for instance be significant changes to the current set-up, e.g. if the housing provider would propose to end the project earlier than planned. Finally, the right of initiative gives tenants the right to put things on the agenda, i.e. the housing provider has to respond and talk with them about issues the tenants want to discuss. Agenda setting power would allow the tenants for instance to discuss the need of a larger meeting space, or to initiate a process whereby the formal delineation of responsibilities between the tenants and the housing corporation can be achieved. Thereafter situations such as described by Joshua, whereby the tenants are suddenly no longer allowed to maintain the electrics, would no longer occur.

Finally, taken as a whole, the combination of all these powers would help both the tenants and the housing corporation to more sharply define the exact goals and ambition levels of the project – as many of the quotes above indicate this structural uncertainty lies behind much friction, overwork and frustration. The incorporation of such rights would also require the tenants to formally articulate their representative mandate towards the other tenants, hopefully reducing the distance towards the wider tenant population and strengthening their negotiating hand in discussions with the housing association.

5 Conclusion: Increasing Tenants Influence through Self-management Needs to Be Integrated with Formal Participation

In this article we have looked at self-management by tenants in a specific project. As such, our conclusions are derived from a single case study. Furthermore, the Startblok Riekerhaven is experimental, rather than a regular landlord-tenant model. While we recognize these limitations of our study, we are confident our conclusions have value beyond this specific case, even if only to inform hypotheses to be tested in future research. Hence, we now return to the research question we posited in the introduction: how can we understand self-management and what could be its added value for tenants’ influence? We observe that the transfer of certain management tasks to tenants does have certain advantages compared to the classical tenant-landlord relationship. Specifically, the tenants in the project do seem to exert more control over their immediate environment, and thus feel more involved. In contrast to the usual focus elsewhere in the literature, where horizontal self-organization is posited as the ideal, we argue that one of the strengths of the project we studied is the hierarchical, pyramidal structure whereby tenants can get involved at different tightly circumscribed levels, requiring different investments of time, and are proportionally financially compensated for their efforts. This makes involvement in the self-management process feasible for a wider group of tenants. Despite the feeling of the parties that the system works quite well, and alignment (at least at an abstract level) about the overall goals of the project exists, we did identify a number of challenges. Communication between the self-management team and the house-owner seems lacking, leading to frustration on the side of the tenants, particularly when matters which directly impact upon them do not seem to receive the necessary attention. The team also seems overburdened by their tasks, and (relatedly) worries about a lack of involvement from the general population of tenants; the impact of the hierarchical pyramid structure on micro-scale interactions between the self-management team and the general population of tenants definitely warrants further research.

Regarding the suboptimal communication, this is partly the result of everybody adjusting to a new, previously untried model, and becoming familiar with the different organizational cultures involved. Nevertheless, one of our key conclusions is that more dialogue and clearer communication channels are not, in themselves, enough. The self-managing tenants, while enjoying a certain level of control over daily management tasks, seem to lack power in the formal sense. Long-established democratic rights in Dutch housing, such as the right to be consulted, the right of approval, and the right to propose, are not visible in this project. If the rights are actually there in theory (which is unclear), they are de facto absent. Without such rights it is questionable whether the self-managing tenants will achieve the interaction they desire with the house-owner, and to raise the issues important to them. Such rights could also help to make abstract goals more concrete, possibly resulting in points of disagreement with the house-owner. In itself this is normal and natural, given the different interests of tenants and landlords. Similarly, the sharpening of the concept of self-management – its goals, its (formal) opportunities and (formal) limitations – could be a good way to involve and activate the wider tenant community in the process, countering the drift towards institutionalization that the self-management team observed.

That said, formal participation structures and democratic power as traditionally deployed in renting relationships in the Netherlands, do not live up to their potential, due to alienation of tenants; a lack of time, knowledge, expertise; the fact that agenda-setting and the determination of the “rules of the game” are still very much in the hands of the landlord; and the fact that the ideal of spontaneous self-organization is unrealistic. Indeed, as noted in the theoretical framework, traditional participation procedures in Dutch housing can function as an instrument for disciplining and responsibilising tenants; a technique of government. Why then might the incorporation of formal participation structures into self-management, succeed? Critically, the difference here is that self-managing tenants, particularly those organized in a hierarchical structure with financial compensation, already have more experience and knowledge than normal tenants, and the pyramidal structure offers some loose approximation of a representative democratic structure and clear channels through which tenants can articulate their viewpoints. The development of expertise amongst the tenants themselves, as opposed to hiring in external experts, is crucial as it prevents the drift towards reliance on external experts who inevitably struggle to understand the on-the-ground realities of living in the project. There are therefore grounds for optimism that formal participation structures and democratic powers will, with self-managed tenants, fall on fertile grounds. In the other direction, we hope that the incorporation of formal participation structures will help mitigate the risk that the self-management team becomes too isolated, frustrated and institutionalized. In short, in a fusion the strengths of each model can be used to mitigate the weaknesses and risks of the other.

This is emphatically not to say that self-managing tenants can or should assume all tasks of the house-owner; this is neither possible, nor desirable. But it is clear that self-managed tenants already have considerable insights and knowledge about many issues that can be of great help to both the tenants and the house-owner. Integrating existing participation structures into self-management is likely to require some careful design. However, by building these powers into future self-management projects, both legally and in the culture of the organization, and making resources (time and money) available, self-management in renting can become a successful hybrid paradigm combining the best parts of traditional renting and self-organization, and avoiding some of the pitfalls of both.

Acknowledgments

We thank our respondents for their kind cooperation, without which this research would not have been possible. Carla Huisman expresses her gratefulness to Steven Kelk for the helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The continuing housing crisis has inspired tenants to join forces against their precarious housing conditions in several European countries such as Spain, Germany (Berliner Mieterverein) and the United Kingdom (Byrne Citation2019). Such tenant unions are recent examples of other forms of self-organization, and can be viewed as political developments countering the obstacles in formal tenant participation discussed below.

2. Olson’s theory is unfortunately often narrowed down to the problem of the free rider. Critique questions the rational-choice assumptions. Olson proposes coercion (as by the state) and economic or social incentives other than the securing of the joint goal as solutions, see Bengtsson (Citation2000) for an application of this theory on housing.

3. A permanent lease cannot be terminated by the landlord unless the tenant is not fulfilling the terms of the contract, such as being in long-time arrears. This derives from the unequal contractual relation between tenants and landlords, which is exacerbated by the increasing scarcity of affordable rental housing.

4. Relatedly, according to Power (Citation2017), the city borough organization that was responsible for managing the Grenfell Tower, and so indirectly for the tragic fire, “masqueraded” for strategic/efficiency reasons as a Tenant Management Organization. The issue here is that, following the fire, some argued that it demonstrated a major flaw with self-management – when, in fact, according to Power, it was a de facto council body without any meaningful tenant involvement.

References

- Aalbers, M., J. van Loon, and R. Fernandez. 2017. “The Financialization of a Social Housing Provider.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 41 (4): 572–587. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12520.

- AFWC (2018) Jaarbericht 2018 - Deel Amsterdam in Cijfers [Year report 2018 – Part Amsterdam in numbers]. Amsterdam, Amsterdam Federation of Housing Corporations.

- Arnstein, S. 1969. “A Ladder of Citizen Participation.” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35 (4): 216–224. doi:10.1080/01944366908977225.

- Bengtsson, B. 2000. “Solving the Tenants’ Dilemma: Collective Action and Norms of Co-operation in Housing.” Housing, Theory and Society 17 (4): 175–187. doi:10.1080/140360900300108618.

- Bradley, Q. 2008. “Capturing the Castle: Tenant Governance in Social Housing Companies.” Housing Studies 23 (6): 879–897. doi:10.1080/02673030802425610.

- Brandsen, T., and Honingh. 2018. “Definitions of Co-Production and Co-Creation.” In Co-production and co-creation: Engaging Citizens in Public Services, edited by T. Brandsen, T. Steen, and B. Verschuere, 9–17. New York/ London: Routledge.

- Bresson, S., and A. Labit. 2020. “How Does Collaborative Housing Address the Issue of Social Inclusion? A French Perspective.” Housing, Theory and Society 37 (1): 118–138. doi:10.1080/14036096.2019.1671488.

- Byrne, M. 2019. “The Political Economy of the ‘Residential Rent Relation’: Antagonism and Tenant Organising in the Irish Rental Sector.” Radical Housing Journal 1 (2): 9–26. doi:10.54825/CDXC2880.

- Cairncross, L., C. Morrell, J. Darke, and S. Brownhill. 2002. Tenants Managing- an Evaluation of Tenant Management Organisations in England. London: Oxford Brookes University with HACAS Chapman Hendy & Office of the Deputy Prime Minister.

- Costarelli, I., R. Kleinhans, and S. Mugnano. 2020. ““Thou Shalt Be a (More) Responsible Tenant”: Exploring Innovative Management Strategies in Changing Social Housing Contexts.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 35 (1): 287–307. doi:10.1007/s10901-019-09680-0.

- Cronberg, T. 1986. “Tenants’ Involvement in the Management of Social Housing in the Nordic Countries.” Scandinavian Housing and Planning Research 3 (2): 65–87. doi:10.1080/02815738608730091.

- Czischke, D. 2018. “Collaborative Housing and Housing Providers: Towards an Analytical Framework of multi-stakeholder Collaboration in Housing co-production.” International Journal of Housing Policy 18 (1): 55–81. doi:10.1080/19491247.2017.1331593.

- Czischke, D., and C. Huisman. 2018. “Integration through Collaborative Housing? Dutch Starters and Refugees Forming self-managing Communities in Amsterdam.” Urban Planning 3 (4): 61–63. doi:10.17645/up.v3i4.1727.

- Dowling, E., and D. Harvie. 2014. “Harnessing the Social: State, Crisis and (Big) Society.” Sociology 48 (5): 869–886. doi:10.1177/0038038514539060.

- Foye, C., D. Clapham, and T. Gabrieli. 2018. “Home-ownership as a Social Norm and Positional Good: Subjective Wellbeing Evidence from Panel Data.” Urban Studies 55 (6): 1290–1312. doi:10.1177/0042098017695478.

- Huisman, C. 2014. “Displacement Through Participation.” TESG 105 (2): 161–174.

- Huisman, C. (2019) ‘Top-down Collaborative Housing?’ Blog on the Co-lab Website, May, https://co-lab-research.net/2019/05/06/1290/

- Huisman, C. (2020) Insecure Tenure- The Precarisation of Rental Housing in the Netherlands. Groningen: Groningen University. 10.33612/diss.120310041.

- Huisman, C., and D. Czischke. 2020. “Samen Wonen Om te Integreren- Hoe Gemengde Woonprojecten Interactie Stimuleren Tussen Vluchtelingen En Nederlandse Bewoners.” Bestuurskunde 29 (3): 45–54. doi:10.5553/Bk/092733872020029003005.

- Huisman, C., and C. H. Mulder. 2022. “Insecure Tenure in Amsterdam: Who Rents with A Temporary Lease, and Why? A Baseline from 2015.” Housing Studies 37 (8): 1422–1445. doi:10.1080/02673037.2020.1850649.

- Hulse, K., A. Morris, and H. Pawson. 2019. “Private Renting in a Home-owning Society: Disaster, Diversity or Deviance?” Housing, Theory and Society 36 (2): 167–188. doi:10.1080/14036096.2018.1467964.

- Hurenkamp, M. (2020) ‘Participatiesamenleving: De Opkomst En Neergang van Een Begrip’. Sociale Vraagstukken www.socialevraagstukken.nl/participatiesamenleving-de-opkomst-en-neergang-van-een-begrip/.

- Jensen, J., and A. Stensgaard (2017) ‘Affordable Housing as a Niche Product: The Case of the Danish “Socialhousing Plus”’. Paper presented at the ENHR Conference Tirana, Albania.

- Key, D. 2015. Ruimte voor beweging- De koers van De Key. Room for Movement- The Direction of De Key. Amsterdam: Woonstichting De Key.

- Kruythoff, H. 2008. “Tenant Participation in the Netherlands: The Role of Laws, Covenants and (Power) Positions.” Housing Studies 23)4 (4): 637–659. doi:10.1080/02673030802116730.

- Lang, R., C. Carriou, and D. Czischke. 2020. “Collaborative Housing Research (1990–2017)- A Systematic Review and Thematic Analysis of the Field.” Housing, Theory and Society 37 (1): 10–39. doi:10.1080/14036096.2018.1536077.

- Lijzenga, L., V. Gijsbers, J. Poelen, and C. Tiekstra. 2019. Ruimte voor Wonen- de Resultaten van het WoonOnderzoek Nederland. Den Haag: Ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties.

- Manz, C. 1992. “Self-leading Work Teams: Moving beyond self-management Myths.” Human Relations 45 (11): 1119–1140. doi:10.1177/001872679204501101.

- Olson, M. 1965. The Logic of Collective Action. Cambridge/ London: Harvard University Press.

- Ostrom, E. 1996. “Crossing the Great Divide: Coproduction, Synergy, and Development.” World Development 24 (6): 1073–1087. doi:10.1016/0305-750X(96)00023-X.

- Palley, T. 2005. “‘From Keynesianism to Neoliberalism: Shifting Paradigms in Economics.’.” In Neoliberalism: A Critical Reader, edited by A. Saad-Filho and D. Johnston, London/Ann Arbor: Pluto Books, 20-29.

- Pawson, H., D. Mullins with, and T. Gilmour. 2010. After Council Housing: Britain’s New Social Landlords. Basingstoke/ New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Polanska, D., and Å. Richard. 2021. “Resisting Renovictions: Tenants Organizing against Housing Companies’ Renewal Practices in Sweden.” Radical Housing Journal 3 (1): 187–205. doi:10.54825/BNLM3593.

- Power, A. (2017) ‘How Tenant Management Organisations Have Wrongly Been Associated with Grenfell’. British Politics and Policy at LSE- blog http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/84698/.

- Rajagopal, B., S. Alfarargi, F. González Morales, F. de Varennes, and O. De Schutter. 2021. Letter to the Dutch Government- Reference AL NLD 3.2021. Geneva, United Nations.

- Rauws, W. 2016. “Civic Initiatives in Urban Development: Self-governance versus self-organisation in Planning Practice.” Town Planning Review 87 (3): 339–361. doi:10.3828/tpr.2016.23.

- Scheller, D., and H. Thörn. 2018. “Governing “Sustainable Urban Development” through Self‐Build Groups and Co‐Housing: The Cases of Hamburg and Gothenburg.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 42 (5): 914–933. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12652.

- Széll, G., P. Blyton, and C. Cornforth. 1989. The State, Trade Unions and Self-Management: Issues of Competence and Control. Berlin/ New York: Walter de Gruyter.

- Uitermark, J. 2009. “An in Memoriam for the Just City of Amsterdam.” City 13 (2–3): 347–361. doi:10.1080/13604810902982813.

- Uitermark, J. 2015. “Longing for Wikitopia- the Study and Politics of self-organisation.” Urban Studies 52 (13): 2301–2312. doi:10.1177/0042098015577334.

- Van Vliet, R., E. Groot, F. Bashir, W. Hachchi, A. Mulder, and P. Oskam. 2014. Ver van Huis- Parlementaire Enquête Woningcorporaties. Den Haag: Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal. https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/kst-33606-4.pdf.