ABSTRACT

In this article, I discuss social housing tenants’ experiences of tenure security and freedom in a housing regime characterized by strong market-orientation and means-testing. Based on thematic analysis of qualitative interviews, I argue that some tenants experience social housing as a haven of stability, whereas others regard it as a source of insecurity that prevents the realization of real personal freedom. These divergent personal experiences reflect the ambiguity of social rented housing in Oslo, a form of housing that for all its market-orientation and means-testing still provides relatively stable long-term homes for many social tenants. By highlighting the link between security and freedom this paper contributes to ongoing theoretical debates in housing studies. The main argument of the paper is that there is a strong connection between the dominant power of landlords in means-tested social housing, restricted tenure security, and the limited positive freedom of social housing tenants.

Introduction

The Norwegian housing regime is one of the more means-tested and market-oriented in Europe (Aarland and Sørvoll Citation2021), and Oslo is no exception to this general picture. In the Norwegian capital, social rented housing (SRH) is targeted at disadvantaged households, and sitting tenants are encouraged to leave SRH by the carrot of subsidized homeownership and the sticks of market-based rents and fixed-term tenancies (Sørvoll Citation2019).

In this article, I ask to what extent SRH-tenants’ experience tenure security and freedom in a highly targeted and residual form of housing. Based on thematic analysis of qualitative interviews, I argue that there are both significant differences and notable similarities between tenants’ subjective experiences of their conditions in the housing market. Some tenants experience social housing in Oslo as a relatively safe haven, whereas others regard its market-based rents and fixed-term tenancies as sources of constant insecurity to the detriment of personal freedom and progress. These variations in subjective experiences may partly be driven by differences in personal circumstances. However, the difference in personal experiences arguably also reflect the ambiguity of SRH in Oslo, that for all its market-orientation and means-testing, still provides (relatively) affordable and stable homes for many tenants. By discussing similarities and variations in personal experiences in a complex housing regime, the article contributes to interlinked debates about security, power, and freedom in housing studies.

The paper is a study of a group that is seldom heard in the public debate and the academic discourse in a nation of homeowners, where more than two-thirds of households are owner-occupiers (Sandlie and Gulbrandsen Citation2017). The study should be of particular interest to academics and practitioners from England, North America, New Zealand, Australia, and other parts of the world that have fully implemented or tested out the use of fixed-term tenancies (Fitzpatrick and Pawson Citation2014; Fitzpatrick and Watts Citation2017), a core characteristic of SRH in Oslo. Furthermore, this paper not only contributes to the growing literature on SRH (Hansson and Lundgren Citation2019) and security (Hulse and Milligan Citation2014; James et al. Citation2020) and freedom (Kimhur Citation2022; King Citation2003; Waldron Citation1991) in housing studies, but also the expanding literature examining the voices of low-income households and other groups experiencing precarity in the housing market (Humphry Citation2020; Listerborn Citation2018, Citation2021).

In what follows, the experiences of fifteen tenants are analysed with reference to the theoretical concepts of tenure security and freedom. These concepts are not new to housing studies but are seldom discussed systematically in relation to each other (see Kimhur Citation2022, for an exception), even though tenure security and residential stability are arguably preconditions for real or positive personal freedom to make progress in key spheres of life (Haman, Hulse, and Jacobs Citation2021). The paper starts with an outline of the housing regime and SRH in Oslo. In the next section, I present and discuss the theoretical concepts of “tenure security” and “freedom”, emphasizing that tenure security is a multidimensional concept, as captured by the term “secure occupancy” (Hulse and Milligan Citation2014), and the distinction between negative and positive freedom. In the theory section of the paper, I also highlight that the considerable discretionary power of local government housing providers in highly means-tested SRH, is a major factor affecting both the tenure security and freedom of tenants. Then I move on to the presentation of the interview sample and the method of qualitative thematic analysis. The next sections of the paper are devoted to the analysis of the patterns in the data, focusing on the similarities and differences in the subjective experiences of security and freedom amongst tenants. In the concluding remarks, I summarize the findings and contributions of the paper. I make the case that there is a strong link between the dominant power of SRH-landlords, limited tenure security and the restricted positive freedom of social housing tenants in situations where the latter have few other decent opportunities in the housing market.

The Housing Regime in Oslo

Housing regime has been defined as “the set of fundamental principles according to which housing provision operates in some defined area (municipality, region, state) at a particular point in time” (Ruonavaara Citation2020, 5). The local housing regime (Hoekstra Citation2020) in Oslo reflects the general characteristics of the national Norwegian regime: deregulated markets for rental- and owner-occupied housing, market-based housing construction, strong emphasis on homeownership promotion, and targeted demand-side subsidies to low-income families (Aarland and Sørvoll Citation2021).

One may briefly describe SRH in Oslo with reference to six characteristics (Johannessen, Hektoen, and Sørvoll Citation2023; MO. Citation2020; Sørvoll Citation2019, 54–55):

Limited size. SRH accounts for approximately four per cent of the housing stock in the city.

Means-tested housing allocation. Only households that are unable to find or afford housing in the private market qualify for SRH: low-income is usually not sufficient to gain entrance. Additionally challenges that make it difficult to access housing in the private market, such as refugee-status, disability, or concurrent substance abuse and mental health disorders, is usually required to qualify for a new SRH-unit.

Fixed-term tenancies. Most new tenants receive three-year fixed-term tenancies.

Market-based rents and means-tested housing allowances. Rents are set by calculating the average market rent of similar dwellings in an area. The poorest tenants receive housing allowances that covers a large proportion of their rent. In 2020, over a third of tenants in Oslo claimed municipal housing allowances.

Homeownership promotion. Tenants are encouraged to buy owner-occupied housing with the help of state subsidized mortgages and housing grants.

Fragmented and business-like administration. The municipal housing company (Boligbygg) owns and lets out housing according to for-profit principles. Oslo’s fifteen boroughs are responsible for the needs-based housing allocation of SRH-units. The social housing bureaucrats working in the boroughs wield considerable discretionary power over housing allocation and the periodic eligibility reviews conducted when tenancies expire.

The case of Oslo stands in sharp contrast to the universal public housing without any formal means-testing in neighbouring Sweden (Grander Citation2019) and is one of the clearest examples of highly targeted social housing in Europe (Aarland and Sørvoll Citation2021). In Oslo, SRH is close to being an “ambulance service”, or “a form of temporary assistance to be withdrawn when tenants cease to ‘need’ it” (Stephens Citation2019, 40). SRH in the Norwegian capital is a scarce resource micromanaged to target households with the greatest perceived needs at any given time. Core characteristics, such as short fixed-term tenancies, market-based rents, and homeownership promotion, are designed to push or motivate the relatively speaking better-off tenants to leave SRH. In this manner, the local government aims to maximize tenant turnover and increase the number of vacant dwellings available to disadvantaged households waiting in line for SRH (Sørvoll Citation2019).

Even though SRH in Oslo is designed to be a temporary alternative for households with the greatest need, it is arguably the best long-term alternative for many disadvantaged groups. Whereas housing allowances and frequent tenancy renewals protect the residential stability of the weakest SRH-tenants, both private rental housing and owner-occupation are challenging market segments for low-income households (Sørvoll, Citation2023). Since the 1990s, property prices have risen sharply, and the low-income homeownership rate has declined (Sørvoll and Nordvik Citation2020). In addition, the private rental sector (PRS) is characterized by limited security of tenure, and private small-scale landlords may deny access to ethnic minorities and low-income households or charge them a premium (FR. Citation2021; Sørvoll and Aarset Citation2015).

Theoretical Concepts: Freedom, Security, and Landlord Power

Many expositions on freedom start by juxtaposing Isiah Berlin’s concepts of negative and positive liberty (Bowring Citation2015; Spector Citation2010). Negative liberty is synonymous with individuals’ freedom to act without obstacles or constraints imposed by others, for instance a central state or local government. Positive liberty may be defined as “the possibility of acting – or the fact of acting – in such a way as to take control of one’s life and realize one’s fundamental purposes” (SEP 2021). For adherents of negative liberty, it is of fundamental importance that people have the formal freedom to make decisions in the markets for goods and services and other spheres of life. Whether individuals have a realistic opportunity or capacity to choose between alternative courses of action is neither here nor there. Defenders of negative liberty like Berlin stress that freedom “is the opportunity to act, not action itself” and that “liberty is one thing, and the conditions for it are another” (quoted from Bowring Citation2015, 157).

The merits of such arguments are rejected by scholars that are inclined towards positive conceptions of liberty. For defenders of positive freedom, real liberty is not being formally free to make decisions but presupposes actual opportunity or power to choose between different alternatives (SEP 2021). According to this line of reasoning, it is not sufficient to have formal rights to choose between adequate alternatives in the housing market; real freedom depends on having the economic and non-economic resources to identify, obtain and maintain a desirable dwelling. T. H. Green, an early advocate of positive liberty, argued that real freedom meant that everyone should have the fair opportunity “to realize his or her capacities to the full” (George Citation2012, 234). This conception of positive freedom is one of the ideological foundations of the post-war welfare state (ibid.).

Amartya Sen’s much cited capability approach stands firmly in the tradition of positive liberty. According to Sen, freedom is both of instrumental and intrinsic value. This means that freedom to choose not only enables desirable welfare outcomes but is also an end, in the sense that there is inherent value in having several plausible courses of action even if it is not possible to choose more than one (Sen Citation2012). Sen draws a distinction between capabilities and human functionings. Capabilities are the freedoms “to achieve valuable combinations of human functionings” (Sen Citation2005, 153), such as adequate nourishment, shelter, happiness, self-respect, political participation and belonging to a community. Unlike the prominent philosopher of virtue ethics Martha Nussbaum (Citation2003), Sen is reluctant to make a definite list of essential human capabilities but prefers to leave their exact specification to public deliberation in societies with different cultural values and living standards (Sen Citation2005).

In recent papers on housing and the capability approach, authors follow the lead of Sen and make no attempt to make a canonical list of capabilities (Foye Citation2021; Kimhur Citation2020). Based on the lessons from theoretical enquiries and empirical studies, however, the realistic opportunity to live in a stable and secure home over time, is a good candidate for the status of a fundamental and undisputed housing capability. Residential stability may not only yield the psychosocial benefit of ontological security, but also contribute to improve welfare outcomes and enable positive freedom to pursue valuable opportunities in life. What is more, the home is a potential source of both physical and financial safety, even though domestic violence or housing market volatility respectively may erode these dimensions of security (Agarwal and Panda Citation2007; Poppe, Collard, and Jakobsen Citation2016).

Following in the wake of works by Giddens and Saunders (Citation1990), the concept of ontological security has gained traction in housing studies (cf. Fitzpatrick and Pawson Citation2014; Fitzpatrick and Watts Citation2017; Hiscock et al. Citation2001). In the words of Giddens, ontological security is the “confidence that most human beings have in the continuity of their self-identity and the constancy of their social and material environments. Basic to a feeling of ontological security is a sense of the reliability of persons and things” (quoted from Hiscock et al. Citation2001, 50). Dupuis and Thorns (Citation1998, 29) argue that homes are foundations for ontological security if they function as sites of constancy, routine, identity construction and life control. Ontological security is often associated with homeownership, but there is reason to believe that households living long-term in the rental sector may also experience psychosocial benefits of residential stability (Fitzpatrick and Pawson Citation2014).

Empirical studies also show that residential stability contributes to desirable welfare outcomes, such as improved educational attainment (Aarland and Reid Citation2019). Moreover, in the literature access to a permanent home of a decent standard is widely seen as a precondition for relative stability and fulfilment in other spheres of life. Building on Nussbaum, King (Citation2003) argues that housing is a freedom right that enables human flourishing. Or put in the words of Haman et al. (Citation2021, 1), there “is increasing research evidence that secure, decent, and affordable housing is a necessary foundation for individuals to participate in economic, social, and cultural life”.

While the home may be source of security in different ways, including financial, physical, and ontological security, I emphasize the importance of tenure security in what follows. A reasonable level of tenure security is arguably a necessary requirement for both ontological security and the attainment of the welfare benefits associated with residential stability. It may also be a necessary foundation for the pursuit of real or positive freedom in the housing market and other spheres of life. The paper’s focus on tenure security does not, however, mean that it has a narrow legal scope: tenure security is a broad multidimensional concept (Byrne and McArdle Citation2022; Hulse and Milligan Citation2014).

An enlightening typology of tenure security is provided by Van Gelder (Citation2010). The typology was originally developed with reference to ownership rights to land and housing in the Global South, however it is also easily adaptable to the study of rental markets in the OECD-area (Hulse and Milligan Citation2014). Van Gelder distinguishes between three forms of security: de jure, de facto and perceptual. In the rental market, de jure security of tenure refers to the legal terms of contract between tenant and landlord. For instance, short fixed-term leases or limited tenant protection from sudden rent increases may arguably be cited as evidence of weak de jure security of tenure. De facto security of tenure is the actual or objective security granted to tenants when all relevant contextual factors are considered. Even though tenants may enjoy a high level of codified legal security, this de jure protection is illusory if they cannot afford to pay rent, or landlords exploit legal loopholes to evict unwanted residents. Perceptual security of tenure is the subjective level of security experienced by tenants. This last category of security may differ significantly from the de facto or objective security postulated by housing researchers or other experts in the field. Tenants will experience reality in a myriad of ways due to their differing life histories, personalities, life phases, social and cultural norms, the influence of the media or other relevant factors (cf. Hulse and Milligan Citation2014; Sørvoll Citation2020).

Hulse and Milligan’s concept of “secure occupancy” is an attempt to capture the variety of factors that may influence the level of de jure, de facto and perceptual security of tenure. They define secure occupancy as “the extent to which households who occupy rented dwellings can make a home and stay there […] subject to meeting their obligations as a tenant” (Hulse and Milligan, 643). These authors also stress that the concept means that people are “able to participate effectively in rental markets; to rent housing with protection of rights as tenants, consumers and citizens; to receive support and assistance from governments if required; and to exercise a degree of control over housing circumstances and make a home” (ibid., 643). In this quote, control over housing circumstances and the ability to participate effectively in rental markets may be seen as aspects of positive freedom. If either of these aspects of secure occupancy is seriously restricted or non-existent tenants’ real opportunity to choose desirable options in the housing market is also limited.

To complete the presentation of the article’s theoretical framework, it should also be added that de facto and perceptual security of tenure is invariably influenced by the asymmetrical power relationship between tenants and landlords. Building on Luke’s concept of the three faces of power, Chisholm et al. (Citation2020) argue that property owners’ domination of tenants may be both obvious and subtle and take visible, hidden, or invisible forms. Recent scholarship on the PRS show that landlord power is often a source of insecurity among tenants (Byrne and McArdle Citation2022; McKee, Soaita, and Hoolachan Citation2020; Soaita and McKee Citation2019). In contexts where the PRS is lightly regulated, such as in England, Ireland, and Norway, landlords have considerable power over tenancy lengths, rent levels and the maintenance and management of rental properties. This means that central aspects of tenants’ living arrangements are unpredictable and controlled by others and that they may therefore experience that they live “at the whim of the landlord”, as stated by one of the tenants interviewed by McKee et al. (Citation2020, 1475).

SRH-landlords have not received the same level of attention in recent scholarship on power relationships in the rental market as their PRS counterparts, even though SRH-landlords have considerable power over the housing circumstances of tenants and therefore may undermine their sense of secure occupancy in different ways. In contrast to homeless individuals who reside in temporary accommodation, SRH-tenants exercise basic control over central aspects of their immediate environment. Their legal rights as tenants means, for instance, that they are free to cook meals, have visitors, and come and go at any hour they please. These rights are likely to be curtailed or non-existent in hostels and other forms of temporary accommodation (Watts and Blenkinsopp Citation2022). Nevertheless, SRH-landlords may control tenants’ housing circumstances through their power over allocation, tenancy lengths, eligibility reviews and rent-setting. In this regard, the power of landlords may both undermine tenure security and weaken the role of housing as a foundation for freedom in different spheres of life. This may be particularly true where SRH-landlords have considerable discretionary power to allow tenancies to expire when conducting eligibility reviews, such as in the case of Oslo (Sørvoll Citation2023).

In democracies, the power of municipal providers of SRH is granted by the elected assemblies that decide on the policies and guidelines that regulate social housing. These guidelines and policies may entail that the SRH-landlord is obliged to protect the interests of both current and prospective tenants. Thus, although a policy such as periodic eligibility review may limit the tenure security and freedom of current tenants, it may also create vacancies that increases the opportunities of households on the waiting list to enjoy the relative security of SRH (Sørvoll, Citation2023).

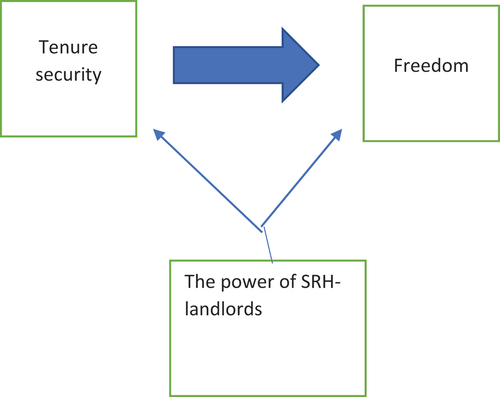

is a simplified theoretical depiction of the relationship between tenure security, freedom, and the power of SRH-landlords. The figure illustrates that landlord power may affect both tenure security and freedom directly. For instance, landlords may undercut tenure security by refusing to renew leases or reduce freedom by limiting the opportunities for tenant mobility within SRH. Moreover, landlord power may have indirect consequences for freedom by curtailing tenure security, in the sense that limited tenure security may reduce the role of housing as a basis of personal freedom.

Methods

In the fall of 2020, face-to-face semi-structured interviews were conducted with fifteen social housing tenants recruited with the assistance of the Tenants Union (Leieboerforeningen) in Oslo. The study was judged to comply with the laws regulating the processing of personal data by SIKT, Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research (reference number: 784153), and all tenants interviewed gave their written consent to participate.

The tenants participating in three focus group interviews and nine single-person interviews represented a wide variety of ages, personal circumstances, and geographical areas in the city. Most had lived for some years in SRH, whilst a few were relative newcomers to this form of housing. The tenants interviewed also had noteworthy similarities as they all – with two exceptions – had experience with tenant activism or participation in democratic governance of SRH-estates. This suggests that the individuals in the interview sample are more politically aware than the average tenant. Otherwise, there is little reason to believe that the interview sample stands apart from the realities of SRH in Oslo. The tenants interviewed share the basic conditions of most SRH-tenants in the city, such as short fixed-term tenancies (with three exceptions), market-based rents, and low incomes. It follows that their subjective experiences, although not representative in a statistical sense, should enrich our general knowledge about the conditions of SRH-tenants in the Norwegian capital. Thus, although personal experiences will invariably vary in their details, my enquiry should have a reasonable level of relevance or transferability (Chenail Citation2010) to tenants not covered in the present study.

The interviews lasted between one to two hours and were transcribed and analysed using descriptive codes constructed with reference to the questions in the interview guide, and the content of the transcripts. These descriptive codes were developed into broader themes or patterns with reference to the theoretical concepts of freedom and tenure security in a broad sense. This means that the thematic analysis was primarily deductive or guided by theoretical concepts (Braun and Clarke Citation2012). In qualitative analysis, a theme “captures something important about the data in relation to the research question and represents some level of patterned response or meaning within the data set” (Braun and Clarke Citation2006, 82). Following the lead of this definition, the themes in this study are based on the tenants’ patterned responses to open questions about security and freedom in social housing with particular emphasis on their experiences with fixed-term tenancies and market-based rent levels.

I have given pseudonyms to the tenants mentioned directly in the text to protect their anonymity. Carefully selected aspects of the informants’ biographies of relevance to the contextual interpretations in the next section are revealed in , including age, tenancy type and number of years lived in SRH:

Table 1. Basic biographical information about the tenants in the study.

Fixed-Term Tenancies and Tenure Security – Empirical Analysis

One of the most striking patterns in the data is the widely different self-reported experiences of fixed-term tenancies. Some of the tenants depicted social housing almost like a safe haven providing shelter from the unpredictability of life in the PRS. Others expressed the view that living with a fixed-term SRH-tenancy was an experience characterized by agonizing anxiety, or a source of insecurity that made it harder to enjoy life and plan for the long-term.

Selma, Roy, Richard, Patricia, and Anthony are examples of tenants that in some ways regarded social housing as a relatively stable form of housing. Anthony did not necessarily plan or hope to stay in SRH beyond his first rental contract. He thought his three-year tenancy provided him with the stability he needed to make progress in his working life and housing career. Roy stated that his fixed-term tenancy “had never weighed him down, because I’ve always counted on that I’ll get five additional years”. Like Roy, Richard was sure that his overall situation would not change much during the next years and was therefore quite confident of getting his lease renewed. Patricia, who had lived with her children in SRH for a long time, was also confident of getting her tenancy extended. She said that “I’m on 5-year contracts because I have kids. So, I’ve just sent in the papers to get it renewed, and I know that I’ll get it renewed”. Similarly, Selma did not see her fixed-term tenancy as a major concern. She admitted that a lifetime lease would have been ideal, but nonetheless thought that her three-year contract provided welcome “breathing space”: “To be sure, I would rather have one of those life-timers, but it is, you know, not to be expected, but I think three years gives me good breathing space, and I have hope that I get an extension”.

Selma’s positive view of renting from the municipality was shaped by her negative view of the PRS:

I feel very comfortable renting from the municipality and not a private landlord, for some reason it feels very safe […]. If you live municipally, it is more permanent, right. With private landlords you do not know if they suddenly need the apartment, if you suddenly need to leave, and I’m not that happy with changes.

Like Selma, other informants opined that SRH provided stronger security of tenure than the PRS. Even some of the tenants that thought that the fixed-term tenancies of the boroughs were a source of insecurity, agreed that SRH was a superior alternative to the PRS in this regard. Maureen had previously rented privately for years and had experienced several disappointing terminations of her tenancies. She stated it was common for PRS-landlords to say, “you can live here as long as you like”, but then change their mind after “maybe two years” and signal that they wanted to use the property themselves. According to Maureen, she had experienced it herself two or three times and thought it was “very exhausting”. Selma and Maureen’s experiences correspond to the reality that PRS-landlords have the legal right to terminate tenancies at short notice by citing a “reasonable cause” (saklig grunn), such as renovation or the need to house themselves or members of their family. These “reasonable causes” are very hard to contest for tenants, something that arguably contributes to making the Norwegian tenancy act quite friendly to the interests of landlords (FR Citation2021).

Paul was one of the tenants that voiced concern about the consequences of fixed-term tenancies in SRH. According to Paul, it was distressing that he could lose his apartment if he became “too healthy” or earned too much. He said that it was hard to settle down properly in the area where he lived, and that residents in social housing “had three years to worry about whether they got their contracts renewed’. Paul knew that most tenants got their leases renewed by the local government but did not personally feel comforted by this information, because “he knew too many that had been forced to move”. Maureen expressed similar sentiments and said that her fixed-term tenancy made her feel “worried” and “insecure”, and that a lease of longer duration would make her apartment feel more like a “home”.

Laura also worried about her long-term future in social housing, and said she had no other alternatives in the housing market because of her meagre disability pension. According to Laura, it was hard to make plans when her housing situation felt insecure. She was not getting any younger and wanted security in her old age and described the process of waiting for an extension of her three-year tenancy as “a bad feeling you walk around with. You don’t know anything”. Astrid also expressed anxiety regarding the local government’s periodic eligibility reviews. In her view, the tenancy review was unpredictable and could go either way: “I see that some people get three-years to begin with, and then they get a life-time tenancy just like that, while others must fight […]. You just don’t know”. Astrid’s point of view reflects the discretionary power of the social housing bureaucrats that conduct eligibility reviews. Moreover, their decisions may seem unpredictable as the practices regarding housing allocation and tenancy renewals vary between the fifteen boroughs (Sørvoll, Citation2023).

Like Paul, Maureen, Laura and Astrid, Anita experienced fixed-term tenancies as a source of insecurity. She voiced vehement opposition to the underlying logic of SRH in Oslo, including the concept of social housing as a transitory tenure for disadvantaged groups. Anita argued that it constituted a grievous abuse of power, that households could lose their right to SRH because other households had even greater needs. In her view, the whole logic of SRH should be turned upside down: “the residents should really decide for themselves how long they can live there. It sounds a bit controversial, but I think it is the most expedient. […] because as long as people live safely, they are also much better equipped to stay in the labour market”.

Anita’s criticism of what she sees as tenure insecurity in Oslo’s SRH, provides an interesting supplement to Marcuse and Madden’s concept of residential alienation. Following the lead of Madden and Marcuse (Citation2016, 59), housing insecurity in the PRS may be described as a form of “residential alienation”, meaning that “households cannot shape their domestic environment as they wish […]. Instead, their housing is the instrument of someone else’s profit and this confirms their lack of social power’. In heavily needs-tested social housing, such as the SRH-sector in Oslo, residential alienation is perhaps rather produced because landlords may use their power to undermine tenure security by using the homes of current tenants as social policy instruments, for instance by allowing tenancies to terminate to create vacancies for severely disadvantaged households. The existence of such tenant-turnover strategies undermined Anita’s sense of tenure security and eroded her confidence in SRH as a safe foundation for participation in the labour market – or what I would call the home as a basis for freedom to pursue valuable objectives.

Nonetheless, far from all the tenants interviewed regard fixed-term tenancies as a source of insecurity or alienation. This illustrates that the level of tenures security in SRH in Oslo is open to interpretation. On the one hand, fixed-term tenancies and eligibility reviews are potential threats to perceptual and de facto tenure security. On the other hand, most rental contracts are renewed, and the average tenant stays around seven years in SRH, much longer than the standard three-year tenancy. Thus, while de jure tenure security is limited, de facto security of occupancy is higher, particularly compared to the PRS (Sørvoll Citation2020), as highlighted by Selma and Maureen.

Moreover, the divergent subjective experiences of fixed-term tenancies partly reflect variations in personal circumstances. For a young adult that regards SRH as a temporary arrangement, such as Anthony, three-year tenancies may be a reasonable foundation for the pursuit of positive freedom in the labour and housing market. Moreover, some of the other tenants did not regard fixed-term tenancies as a threat to their tenure security because they represented household categories that often get their tenancies renewed, such as Patricia, who had children, and Roy, who had retired several years ago (Johannessen, Hektoen, and Sørvoll Citation2023). Others, such as Anita, were not in one of these categories and therefore may have had more reason to experience SRH as a source of insecurity that provided no real foundation for freedom in other spheres of life. Almost the exactly the opposite may be said of Selma, who had a very negative view of the PRS, and cherished the stability provided by SRH.

Market-Based Rents, Limited Freedom, and Lack of Control – Empirical Analysis

For some tenants it was not the fixed-term tenancies that threatened de facto and perceptual tenure security, but other housing related aspects of life, including market-based rents and the practices of the municipal landlord. Elisabeth, who had lived in the same flat since the mid-1990s, expressed concern that the constantly rising market-based rent levels would price her out of the home and neighbourhood she cherished. Similarly, Theresa also worried that rents would drive her out of the borough she had lived since the late 1980s. Two other tenants, Richard and Louise, said they considered leaving the city and the market-based rent system behind, and settle in another country with lower housing expenses. Richard stated that the periodic rent increases were constant sources of “unpredictability” that were amplified by the lack of any explanation or justification by the borough.

Patricia and Paul warned about the detrimental consequences of the market-based rent system for their personal progress – or what I term the positive freedom to pursue opportunities they value. According to Patricia, the rent setting system made it impossible to take some time off work and invest in an education: “I don’t have a three-year college degree, but if the rent was much lower, I would have rushed off to school many, many years ago and got myself a higher education”. Paul also felt the SRH-system limited his freedom to plan for the long term. The market-based rent system meant that he was unable to save money and relied on the social services for emergency cash many months of the year. Paul said it was possible for him to live a more independent life in which necessary expenses did not have to be controlled and approved by the social services, but only if the rent setting system had been more in sync with the income of the tenants. Market-based rents not only meant that he had to buy cheap second-hand kitchen appliances approved by the social services, but also that he could not afford going anywhere that cost him money. Thus, while emergency payments from the social services boosted Paul’s short-term tenure security, it left him in a form of welfare dependency that limited his positive freedom in other spheres of life.

Whereas Patricia and Paul lacked the positive freedom to pursue valuable opportunities, Selma experienced the combination of market-based rents and housing allowances as liberating: “It works fantastically well for me, you know. The rent is 10,700 a month, but I get housing allowances, so the actual rent is only 4100. And this means I suddenly feel that I have a lot of money”. For Selma, it had been “such a relief to get the municipal apartment […] and that housing allowance” since it increased her tenure security and disposable income compared to when she resided in the PRS. Significantly, only SRH-tenants are eligible for municipal housing allowances, a subsidy which is more generous than the state housing benefit that covers all tenants regardless of sector (Sørvoll, Citation2023).

It is perhaps not surprising that Selma, and not Patricia and Paul, experienced SRH as a boost to her freedom in life. Unlike Paul and Patricia, she had recent negative experiences as a tenant in the PRS, and as part of the approximately forty percent of SRH-tenants who qualified for means-tested municipal housing allowances (Johannessen, Hektoen, and Sørvoll Citation2023), she did not have to rely on emergency cash from the social services like Paul.

Some of the other tenants interviewed, voiced the opinion that unpredictable behaviour and lack of information from the municipal landlord were sources of tenure insecurity. To mention one example, Roy said that he had heard unconfirmed rumours that the building where he lived was about to be refurbished or even demolished. Even though there had been an article in the local paper giving credence to the rumours, he had heard nothing about it directly from the local authorities. According to Roy, the rumours were “a pretty frequent topic of conversation” amongst tenants in the building and many of them were “nervous” about the future. Roy said that one could ask the housing company about anything, but that it was like “shouting in the woods, you won’t get an answer, you know”. Nadia was also distressed about the limited communication and information from the municipal housing company concerning what she experienced as a disruptive refurbishment of her building.

The lack of information and transparency experienced by Roy, Nadia, and others, illustrates that the informants struggle to realize one of the conditions of secure occupancy, namely “a degree of control over housing circumstances” (Hulse and Milligan Citation2014, 643). All tenants interviewed also provided further examples that illustrated their limited freedom to influence significant factors affecting their contemporary and future housing circumstances.

None of the informants experienced that they had any real freedom of choice when it came to the rent level, standard and location of their apartment. Anita said that “if you get municipal housing that is where you are going to live. Full stop”. When people are offered a municipal home in one of the city’s fifteen boroughs, it is a question of “take it or leave it”, according to Laura: “You don’t get any options. If you’re offered […] you have to take it. If you don’t want it, you will not get an apartment. Done. That’s the way it is”.

Paul tells the story of getting a flat in a borough he had very few prior ties. According to Paul, he was told by the local government that it was wise to sign the contract and stop worrying, even though he personally felt the rent was too high. Paul said that the municipality did not enquire about his housing needs, and that nobody offered him any alternatives when it came to size, price and location. He would prefer to move to a smaller apartment in an area with a lower market rent, but that was not an option put on the table by the local authorities.

Paul’s experience reflects not only that tenants’ secure occupancy is undermined by limited control of their own housing circumstances, but also the imbalanced power relationship between tenants and landlords in Oslo’s SRH. For instance, it is the landlords who decide where, for how long and under what terms tenants may access social housing. When it comes to location, size, standard, rent-level, and tenancies there is very little freedom of choice for SRH-tenants (Author, 2023). Thus, most of the housing-related living conditions vital for the tenure security and personal freedom of tenants are controlled by SRH-landlords. For sitting SRH-tenants, it is for example almost impossible to change to an apartment in another part of own. The boroughs have no administrative responsibility for the welfare of tenants registered in another part of city, and fear the costs related to childcare, social assistance, and other services following in the wake of welcoming new social housing tenants (Johannessen, Hektoen, and Sørvoll Citation2023).

The fact that SRH tenants often lack good exit-options in the private market arguably contributes to increasing the relative power of SRH-landlords and limits the positive freedom and tenure security of tenants in a broad sense. As indicated by the interviews with Anita, Laura and Paul, tenants only have the nominal freedom to refuse an apartment from the local government. Because of a shortage of decent options in the private market, whether because of discrimination and limited de jure security in the PRS or high prices in the market for owner-occupied housing (Sørvoll and Aarset Citation2015; Sørvoll and Nordvik Citation2020), their positive freedom to refuse an offer is limited at best. In this sense, they are at the mercy of the power of the municipal landlord when it comes to most aspects of their housing circumstances, and because of limited choices outside the SRH they may hardly be considered to participate or compete “effectively in rental markets” (Hulse and Milligan Citation2014, 643), and thus fall short of many of the requirements of secure occupancy or tenure security in a broad, multidimensional sense.

Concluding Remarks

In this article, I have analysed the subjective experiences of freedom and tenure security amongst fifteen tenants residing in SRH in Oslo. Some of the tenants interviewed, such as Paul, Maureen, and Laura, expressed the view that the fixed-term tenancies of SRH housing created insecurity that made it difficult to plan and realize their potential in other spheres of life. Thus, insecurity created less freedom in the positive sense.

The qualitative data also reflect that the secure occupancy of the tenants interviewed was undermined by market-based rents, lack of information, unpredictability, and the discretionary power of SRH-landlords, as well as their restricted capacity to compete in the rental market and influence their own housing circumstances. The domination of landlords and tenants’ limited power to control and choose means that the latter had limited positive freedom to pursue valuable opportunities in the housing market and other spheres of life. By highlighting this connection between tenure security (cf. Fitzpatrick and Watts Citation2017; Hulse and Milligan Citation2014) and positive freedom (cf. Kimhur Citation2020, Citation2022) this paper merges insights from different strands of the housing studies literature. The main theoretical lesson of the paper is arguably that there is a strong connection between the dominant power of SRH-landlords in highly means-tested social housing, limited tenure security, and seriously restricted positive freedom of tenants in contexts where the latter have few decent alternatives in the private housing market.

That noted, Selma and Anthony are examples of informants that experienced SRH in Oslo as a relatively secure housing alternative that boosted their positive freedom. Both opined that their fixed-term tenancies provided them with the stability they needed to move on with their lives, and Selma’s status as recipient of municipal housing allowances provided her with a sense of newfound relative prosperity. The divergent experiences of SRH in Oslo amongst the tenants certainly reflect variations in their exact circumstances, as shown above. However, the divergent perspectives in the data are arguably also explained by the specific character of the SRH in Oslo. Despite all its market-orientation, needs-testing, and eligibility reviews, SRH in the Norwegian capital still provides relatively affordable long-term homes for many tenants with few other options. In other words, SRH in Oslo is ambiguous and open to different plausible interpretations depending on the circumstances and perspectives of the beholder.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Anne Rita Andal of the Tenants Union in Oslo for help with recruiting informants, and Katja Johannessen from the local government (Velferdsetaten/Welfare Agency & VID Specialized University) for our research collaboration and many interesting conversations about social housing in later years. I would also like to thank Maja Flåto for good comments to an earlier version of this paper, as well as three anonymous referees that helped improve the quality of the paper substantially. Lastly, the tenants that participated in the study have my gratitude.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aarland, K., and C. Reid. 2019. “Homeownership and Residential Stability: Does Tenure Really Make a Difference?” International Journal of Housing Policy 19 (2): 165–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2017.1397927.

- Aarland, K., and J. Sørvoll. 2021. Norsk boligpolitikk i internasjonalt perspektiv [Norwegian housing policy in international perspective]. Oslo: NOVA.

- Agarwal, B., and P. Panda. 2007. “Toward Freedom from Domestic Violence: The Neglected Obvious.” Journal of Human Development 8 (3): 359–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649880701462171.

- Bowring, F. 2015. “Negative and Positive Freedom: Lessons From, and To, Sociology.” Sociology 49 (1): 156–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038514525291.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2012. “Thematic Analysis.” In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, and K. J. Sher edited by, Vol. 2, Washington DC, DC: American Psychological Association 57–71. Research Designs https://doi.org/10.1037/13620-004.

- Byrne, M., and R. McArdle. 2022. “Secure Occupancy, Power, and the Landlord-Tenant Relation: A Qualitative Exploration of the Irish Private Rental Sector.” Housing Studies 37 (1): 124–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2020.1803801.

- Chenail, R. J. 2010. “Getting Specific About Qualitative Research Generalizability.” Journal of Ethnographic & Qualitative Research 5 (1): 1–11.

- Chisholm, E., P. Howden-Chapman, and G. F. And. 2020. “Tenants’ Responses to Substandard Housing: Hidden and Invisible Power and the Failure of Rental Housing Regulation.” Housing, Theory & Society 37 (2): 139–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2018.1538019.

- Dupuis, A., and D. C. Thorns. 1998. “Home, Home Ownership and the Search for Ontological Security.” The Sociological Review 46 (1): 24–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.00088.

- Fitzpatrick, S., and H. Pawson. 2014. “Ending Security of Tenure for Social Renters: Transitioning to ‘Ambulance Service’ Social Housing?” Housing Studies 29 (5): 597–615. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2013.803043.

- Fitzpatrick, S., and B. Watts. 2017. “Competing Visions: Security of Tenure and the Welfarisation of English Social Housing.” Housing Studies 32 (8): 1021–1038. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2017.1291916.

- Foye, C. 2021. “Ethically-Speaking, What is the Most Reasonable Way of Evaluating Housing Outcomes?” Housing, Theory & Society 38 (1): 115–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2019.1697356.

- FR. 2021. Å leie bolig [To rent a home]. Oslo: Forbrukerrådet.

- George, V. 2012. Major Thinkers in Welfare. Bristol, UK: The Policy Press.

- Grander, M. 2019. “Off the Beaten Track? Selectivity, Discretion and Path-Shaping in Swedish Public Housing.” Housing, Theory & Society 36 (4): 385–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2018.1513065.

- Haman, O. B., K. Hulse, and K. Jacobs. 2021. “Social Inclusion and the Role of Housing.” In Handbook of Social Inclusion, edited by P. Liamputtong. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-48277-0_130-1.

- Hansson, A. G., and B. Lundgren. 2019. “Defining Social Housing: A Discussion on the Suitable Criteria.” Housing, Theory & Society 36 (2): 149–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2018.1459826.

- Hiscock, R., A. Kearns, S. MacIntyre, and A. Ellaway. 2001. “Ontological Security and Psycho-Social Benefits from the Home: Qualitative Evidence on Issues of Tenure.” Housing, Theory & Society 18 (1–2): 50–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036090120617.

- Hoekstra, J. 2020. “Comparing Local Instead of National Housing Regimes? Towards International Comparative Housing Research 2.0.” Critical Housing Analysis 7 (1): 74–85. https://doi.org/10.13060/23362839.2020.7.1.505.

- Hulse, K., and V. Milligan. 2014. “Secure Occupancy: A New Framework for Analysing Security in Rental Housing.” Housing Studies 29 (5): 638–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2013.873116.

- Humphry, D. 2020. “From Residualisation to Individualization? Social Tenants’ Experiences in Post-Olympics East Village.” Housing, Theory & Society 37 (4): 458–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2019.1633400.

- James, B. L., L. Bates, L. Coleman, M. T. R. Kearns, and F. Cram. 2020. “Tenure Insecurity, Precarious Housing and Hidden Homelessness Among Older Renters in New Zealand.” Housing Studies 37 (3): 483–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2020.1813259.

- Johannessen, K., M. Hektoen, and J. Sørvoll. 2023. Når kontrakten går ut [When the tenancy ends]. HOUSINGWEL Working Paper 1/23. Oslo: NOVA.

- Kimhur, B. 2020. “How to Apply the Capability Approach to Housing Policy? Concepts, Theories and Challenges.” Housing, Theory & Society 37 (3): 257–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2019.1706630.

- Kimhur, B. 2022. “Approach to Housing Justice from a Capability Perspective: Bridging the Gap Between Ideals and Policy Practices.” Housing Studies 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2022.2056148.

- King, P. 2003. “Housing as a Freedom Right.” Housing Studies 18 (5): 661–672. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673030304259.

- Listerborn, C. 2018. Bostadsojämlikhet: röster om bostadsnöden. Stockholm, Sweden: Premiss förlag.

- Listerborn, C. 2021. “The New Housing Precariat: Experiences of Precarious Housing in Malmö, Sweden”.” Housing Studies 38 (7): 1304–1322. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2021.1935775.

- Madden, D., and P. Marcuse. 2016. In Defense of Housing. London, UK: Verso.

- McKee, K., A. M. Soaita, and J. Hoolachan. 2020. “‘Generation rent’ and the Emotions of Private Renting: Self-Worth, Status and Insecurity Amongst Low-Income Renters.” Housing Studies 35 (8): 1468–1487. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2019.1676400.

- MO. 2020. Kommunal Boligbehovsplan 2021-2030 [Municipal Housing Needs Plan]. Oslo: Oslo kommune.

- Nussbaum, M. 2003. “Capability as Fundamental Entitlements: Sen and Social Justice.” Feminist Economics 9 (2–3): 33–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/1354570022000077926.

- Poppe, C., S. Collard, and T. B. Jakobsen. 2016. “What Has Debt Got to Do with It? The Valuation of Homeownership in the Era of Financialization.” Housing, Theory & Society 33 (1): 59–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2015.1089934.

- Ruonavaara, H. 2020. “Rethinking the Concept of ‘Housing Regime’.” Critical Housing Analysis 7 (1): 5–14. https://doi.org/10.13060/23362839.2020.7.1.499.

- Sandlie, H. C., and L. Gulbrandsen. 2017. “The Social Home Ownership Model – the Case of Norway.” Critical Housing Analysis 4 (1): 52–60. https://doi.org/10.13060/23362839.2017.4.1.324.

- Saunders, P. 1990. A Nation of Homeowners. Oxon, UK: Unwin Hyman.

- Sen, A. 2005. “Human Rights and Capabilities.” Journal of Human Development 6 (2): 151–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649880500120491.

- Sen, A. 2012. “Development as Capability Expansion.” In The Community Development Reader, edited by J. Defillipis and S. Saegert, 319–327. New York: Routledge.

- SEP (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy). 2021. “Positive and Negative Liberty”. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/liberty-positive-negative/.

- Soaita, A. M., and K. McKee. 2019. “Assembling a ‘Kind of’ Home in the UK Private Renting Sector.” Geoforum 103:148–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.04.018.

- Sørvoll, J. 2019. “The Dilemmas of Means-Tested and Market-Oriented Social Rental Housing: Municipal Housing in Norway 1945-2019.” Critical Housing Analysis 6 (1): 51–60. https://doi.org/10.13060/23362839.2019.6.1.460.

- Sørvoll, J. 2020. Bostabilitet Vs. Sirkulasjon: Botrygghet I Kommunale Boliger I Oslo? [Residential Stability Vs. Tenant Turnover: Secure Occupancy in Municipal Housing in Oslo?]. Oslo: NOVA.

- Sørvoll, J. 2023. “The Great Social Housing Trade-Off. ‘Insiders’ and ‘Outsiders’ in Urban Social Rental Housing in Norway”. Forthcoming in Housing Studies.

- Sørvoll, J., and M. F. Aarset. 2015. Vanskeligstilte på det norske boligmarkedet [The disadvantaged in the Norwegian housing market]. Oslo: NOVA.

- Sørvoll, J., and V. Nordvik. 2020. “Social Citizenship, Inequality and Homeownership. Postwar Perspectives from the North of Europe.” Social Policy & Society 19 (2): 293–306. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746419000447.

- Spector, H. 2010. “Four Conceptions of Freedom.” Political Theory 38 (6): 780–808. https://doi.org/10.1177/0090591710378589.

- Stephens, M. 2019. “Social Rented Housing in the (DIS)United Kingdom: Can Different Social Housing Regime Types Exist within the Same Nation State?” Urban Research & Practice 12 (1): 38–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2017.1381760.

- Van Gelder, J. L. 2010. “What Tenure Security? The Case for a Tripartite View.” Land Use Policy 27 (2): 449–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2009.06.008.

- Waldron, J. 1991. “Homelessness and the Issue of Freedom.” UCLA Law Review 39:295–324.

- Watts, B., and J. Blenkinsopp. 2022. “Valuing Control Over One’s Immediate Living Environment: How Homelessness Responses Corrode Capabilities.” Housing, Theory & Society 39 (1): 98–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2020.1867236.