ABSTRACT

This article explores the way local states can challenge the process of housing financialization, by focusing on policy innovation for housing vulnerability. Building upon theoretical discourses that emphasize the influence of financial investors in shaping policy frameworks, we suggest that institutional settings that develop independently of financial logics and prioritize social policies can both incite shifts in financial investors’ strategies and change the dynamics in the financialization of housing. This is the case even within rental systems where local states demonstrate limited capacity to intervene in housing markets. Using desk-based research and interviews with expert informants, this study investigates the way new municipalism policies have addressed housing vulnerability in Barcelona. It considers investors’ responses to an institutional framework that prioritized social criteria, and interrogates the relation between housing policy and financial innovation. Key findings suggest that housing financialization is a dynamic process, contingent on the way different actors interrelate and mutually redefine power relations in housing affairs.

Introduction

Housing has been increasingly perceived as an(other) asset class that generates steady capital returns. This is a key topic in the academic discussion on housing financialization which scrutinizes the manner in which financial innovation, in tandem with policy deregulation and re-regulation (Aalbers Citation2016), has generated liquidity out of the spatial fixity of homes (Gotham Citation2009). The state is considered as a decisive actor, as changes in macroprudential, planning and property rights regulations de-risk financial investments in local real estate markets (Lapavitsas Citation2014). As the financial industry’s networked character substantially influences policymakers across state scales (Karwowski Citation2019), it is likely that housing policies are prone to accommodate financial interests. However, the state is a dynamic social relation fraught with internal contradictions (Jessop Citation1990) that impinge on how different state actors react under the influence of broader political, social, and economic events (Brenner Citation1999). Such contradictions have the potential to challenge policymaking processes that promote financial interests, and to curtail or reverse the financialization of housing in alignment with Wijburg’s (Citation2021) plea for de-financialization.

Over the past decade, throughout Europe numerous local governments led by progressive coalitions have demonstrated that the state’s transformative capacity can be harnessed to redefine local welfare and address issues of housing affordability (Janoschka and Mota Citation2021; Russell Citation2019; Thompson Citation2021). Barcelona stands as a paradigmatic example of such a shift towards new municipalism, that operates “in, against, and beyond neoliberalism” (Featherstone, Strauss, and MacKinnon Citation2015). To counteract the ramifications of the “Barcelona model” of urban growth and the impact of the global financial crisis on housing (Blanco Citation2015; Charnock, Purcell, and Ribera‐Fumaz Citation2014), social campaigns have placed the right to housing at the epicentre of political claims, which mobilized support for a progressive candidate for municipal leadership. From 2015 until 2023, Ada Colau, the charismatic former spokesperson of the Platform of Mortgage Affected People (la Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca – La PAH), held the position of Mayor of Barcelona. Such new municipalists do not reify the local state, but rather consider it as a strategic entry point for practising redistribution of economic and political power (Russell Citation2019). Within this framework, novel policies were launched to tackle housing vulnerability (Bianchi Citation2023; Blanco, Salazar, and Bianchi Citation2020). However, such progressive policy measures are viewed as potentially disruptive to what is referred to as market stability, prompting investors to reallocate portfolios or to wind down investments (Fuller Citation2021). Nevertheless, eight years after the introduction of new municipal housing policies, substantial financial investments in Barcelona’s housing sector persist, with no observable disinvestment transactions.

Despite academic insights into the role of the state vis-à-vis the profitability strategies of institutional investors in the financialization of housing, there is no evidence of how state and market actors negotiate and interpret housing problems such as housing vulnerability, affordability pressures, and evictions, within changing institutional frameworks that prioritize social matters; or how they reposition themselves in redefining power relations in housing markets. To address these questions, the research objectives of this article are to explore: (i) how policies address housing vulnerability within the context of new municipalism; (ii) how investors perceive and respond to a changing institutional framework that prioritizes social and housing vulnerability; and (iii) whether there is a relation between housing policy and financial innovation.

The article is structured as follows. First it revisits the housing financialization literature to scrutinize state policies launched to de-risk financial investments, and the role of the local state and institutional investors’ strategies in exploiting local housing markets. This is followed by an outline of the methods employed in this research. The third section shifts attention to the way housing financialization plays out in Spain, and explores housing policy innovation in Barcelona. The fourth section analyses investor responses to changing institutional frameworks, by focusing on corporate social responsibility programmes as financial innovation to further de-risk investments. Concluding remarks underscore this article’s contribution by showcasing the interplay between housing policy and financial innovation, providing evidence that re-regulatory efforts incite investors to adapt to new institutional frameworks and open up novel ways for them to maintain their profitability margins intact.

State Policies and Business Logics in the Financialization of Housing

The financialization of housing refers to the ongoing structural changes in housing and financial markets, whereby housing is treated as a means for accumulating wealth, and as a security traded and sold on global markets (UN report Citation2017). Literature in the field initially examined how financial innovation, in the form of mortgage credits traded as securities in global financial markets (Alexandri and Janoschka Citation2018; Fields Citation2018), resulted in debt-driven practices of asset accumulation for institutional investors (Alexandri Citation2022). Increasingly, emphasis has been placed on the way financial innovation allowed investors to borrow against anticipated increases in future rents and property values, a practice characterized as assetization (see Birch and Muniesa Citation2020), or to securitize rent revenues to further finance expansion in niche markets (Nethercote Citation2020), pointing towards asset-driven practices of property accumulation.

The role of the central state is considered vital to facilitate housing financial investors, mainly through setting an institutional framework that de-risks investments, and therefore enables financial operations (Aalbers et al. Citation2023; Belotti and Arbaci Citation2021). De-risking entails a regulatory dimension that relies on removing barriers that prevent stakeholders from investing in new asset classes. This also relates to welfare restructuring, which includes budget reductions in education, pensions, and health and care systems, enabling the emergence of relevant private markets (Peck, Brenner, and Theodore Citation2018). De-risking also encompasses a macro-economic perspective, reallocating fiscal resources to align the risk/return features of new asset classes with investor preferences (Gabor and Kohl Citation2022). Within the context of housing, besides the transfer of portfolios of distressed assets to institutional investors, the privatization of public housing has given rise to privately-rented housing markets. As underscored in urban political economy discourses, this restructuring is coupled with labour casualization and more stringent mortgage criteria (Byrne Citation2016; Wijburg Citation2019), making investments in privately-rented housing markets risk-averse, as housing demand is secured due to lack of other housing options. Macroeconomic and fiscal de-risking were further associated with the advocacy of quantitative easing policies and low-interest rates, which were implemented until recently, and positioned real estate as a lower-risk and higher-yielding investment compared to other asset classes. Moreover, amendments in regulative frameworks for real estate investment trusts (REIT), which provide tax benefits to shareholders or corporate tax exemption, have triggered financial investors to participate in residential real estate due to such favourable risk/return ratios (Janoschka et al. Citation2020).

While central state policies essentially de-risked financial investments in local housing markets, local states engaged with financial practices that exposed public funds to financial risks as an outcome of post-crisis neoliberal restructuring. Local states, distressed by budget cuts and shrinking tax revenues, shifted their priorities from redistributive policies to wealth creation (Cochrane Citation2007). Urban infrastructure, public assets and land were exploited in entrepreneurial ways, underscored by profit-seeking strategies (Savini Citation2017; Van Loon, Oosterlynck, and Aalbers Citation2019). For instance, in urban planning, the prioritization of a planning gain mechanism was outlined by the need to secure financial and economic benefits from property developers as a precondition for granting planning permission (Ferm and Raco Citation2020; Savini Citation2017). Additionally, municipal governments started to convert income streams from public assets into financial products, through schemes like tax increment financing, which was used to fund public infrastructure in targeted areas through private investments, so as to generate wealth and produce profit (Karwowski Citation2019; Weber Citation2015). At the same time, as municipal governments engaged entrepreneurially with financial logics, they became increasingly reliant on capital markets and financial risks to promote urban growth and facilitate financial investors (Beswick and Penny Citation2018; Çelik Citation2021). This structural transformation of the local state (Ward Citation2017) pointed towards a financialized form of urban governance, which was underpinned by projects that were financially mediated by or developed in conjunction with financial actors (Van Loon, Oosterlynck, and Aalbers Citation2019).

However, new evidence shed light on local governments’ regulatory efforts as a response to housing affordability pressures, and examined policy experimentation to curb real estate speculation (Kettunen and Ruonavaara Citation2021). For example, in 2019, New York State (USA) passed a major revision to rent regulations, to safeguard tenants from rent hikes; the city of Berlin (Germany), allocated potential sites for new construction to municipal housing companies to lower construction costs; and Vienna’s response (Austria) to a mounting housing shortage was to restart council housing construction (Kadi, Vollmer, and Stein Citation2021). In a distinctive scenario, evidence from Amsterdam (Netherlands), where the local state controls 80% of the urban land, showcased a novel form of regulated marketization within the private rented housing sector (Hochstenbach and Ronald Citation2020). Amsterdam municipality’s ability to guide market dynamics in new real-estate developments relied on policies that dampened rent increases and regulated new constructions (Uitermark, Hochstenbach, and Groot Citation2023). Although this kind of reforms aimed to expand the available affordable housing stock and regulate rents in the private rental sector, rents nevertheless persistently increase, rendering housing increasingly unaffordable. Moreover, regulative efforts at the local level are often ruled-out by policies at other state scales or even by court decisions, such as the rent cap policy of the state of Berlin, which was overruled by the German Constitutional Court (Holm, Alexandri, and Bernt Citation2023). In other cases, such as Vienna, policy measures have prompted developers to circumvent regulations and commodify rent-regulated housing (Musil, Brand, and Punz Citation2022).

Housing affordability pressures are attributed to financial investors’ activities in local housing markets (Haffner and Hulse Citation2021). Financial investors engage with housing in ways that enable profitmaking akin to interest-bearing capital investments (Adkins, Cooper, and Konings Citation2021), with a primary focus on consolidating strategies that ensure a continuous flow of rents (Wijburg, Aalbers, and Heeg Citation2018). At the same time, a key prerequisite is to further de-risk investments and guarantee existing profitability margins in ways that open up new opportunities for market expansion (Holm, Alexandri, and Bernt Citation2023). For example, the acquisition of properties catering to welfare recipients has evolved into a risk-averse strategy, given that state benefits guarantee consistent monthly rent payments (Bernt, Colini, and Förste Citation2017). Moreover, financial housing investors expand through acquisitions (Fields Citation2018), and diversify portfolios to specialize in certain types of properties that showcase capital turnover (e.g. luxury housing; Built-to-Rent), or target the needs of specific social groups (e.g. students, the elderly, mobile professionals). Profitability is further maintained by operational cost reduction, which is achieved either through marginal maintenance, via efficiency gains operationalized through digitization of housing stock management (Janoschka et al. Citation2020), or via valuation gains stemming from accounting practices that demonstrate increased balance sheet assessment of future potential values, which can then be used as collateral for borrowing capital (Holm, Alexandri, and Bernt Citation2023). Nonetheless, property investments are not independent, but remain closely linked to broader economic and regulatory processes. Therefore, reforms and regulations introduced at different state scales have significant impact on market actors’ strategies and behaviour (Taşan-Kok and Özogul Citation2021). Considering this, the next section explains the methodology of the research reported in this article, followed by a third section that examines the specificities of housing financialization in Spain, and changes in the regulatory framework during Barcelona’s new municipalism housing policies.

Research Methods and Data Analysis

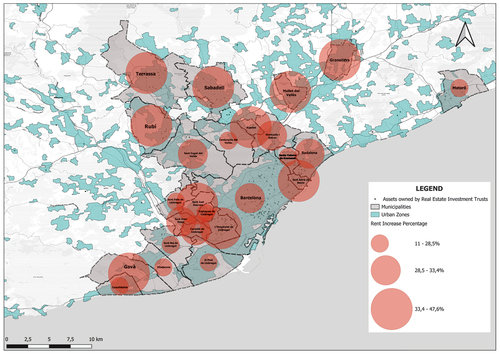

This article is rooted in a research project that compares the process of housing financialization in Barcelona with other EU cities. The focus lies on housing policies, and on the profile of financial housing investors and their strategies in local housing markets. The empirical investigation in Barcelona unfolded in three stages. Initially, desk-based research was conducted by compiling data from real estate market reports and financial journalism regarding the profiles of housing investors in Barcelona. Upon identifying the real estate investment trusts (REITs – SocimisFootnote1 in Spanish) listed on the Spanish stock exchange, further information was sourced from companies’ annual reports. This relied on compilation of data on the main participating capital shareholders, which was subsequently cross-referenced with information obtained from Orbis, a database that contains detailed company data. The collected data was organized to identify the key financial residential investors in Barcelona (). Additionally, the exact location of assets owned by financial investors was traced in their companies’ annual reports. Data was then geocoded onto a GIS map, creating a first layer of information. A second layer of information detailing rent levels spanning the period from 2013Footnote2 to 2021 was developed. Data on rental levels during this timeframe were acquired from the Idealista real estate website (, Map). Non-participant observation in real estate fairs and expert discussions (such as at SIMA in Madrid and SIMA Barcelona) helped to identify key informants in the real-estate industry, who were subsequently approached for expert interviews (see below).

In the second stage, desk-based research into housing policies in Spain across state scales evolved into specific analysis of the grey literature and official reports pertaining to local housing policies in Barcelona. This was further supported by data gathered from housing campaigner’s webpages (such as the PAH Barcelona and the Tenants’ Union) regarding pressing cases of eviction and the organization of housing struggles. Through this approach, the gatekeepers of housing campaigns were identified as key informants.

In the third stage, empirical research took the form of 26 expert in-depth interviews with informants from real estate and financial markets, real estate agents, policy-makers, academics and activists (see ). Lastly, the research received additional support from in-situ observations during the weekly meetings of the Tenants’ Union in Barcelona, from September to November 2019. These observations contributed to a thorough understanding of housing vulnerability.

Table 1. Overview of interview profiles.

The interviews aimed to provide an in-depth understanding of the logics motivating the asset management of housing investors, and policymakers’ rationale for addressing housing vulnerability pressures. Questions were crafted to identify how each actor reacts under the influence of the other. Interviewees were selected for their activities in local real-estate housing markets (real estate agents and directors in REITs), for their detailed knowledge of local housing (academics), and for their position in designing (individuals with a position in local or regional administration) or influencing (activists with direct lines of communication with financial investors and local policymakers) housing affairs. provides an overview of the interviewee profiles and the interview content. All interviews were anonymized, transcribed and their content was qualitatively analysed via the Nvivo software.

Housing Financialization in Spain, and Housing Policies Under Municipal Changes in Barcelona

In Spain, the financialization of housing is rooted in a three-stage schema of urban development that first, promoted homeownership as the preferred form of tenure; secondly, it facilitated credit financing as a crucial means to ensue homeownership (Alexandri and Janoschka Citation2018); and, lastly, it dismantled mortgaged homeownership through policies that enabled property acquisition by financial investors (Colau and Alemany Citation2014; Coq‐Huelva Citation2013; Palomera Citation2014). More precisely, in the aftermath of the 2007 global financial crisis, chain defaults among developers and households resulted in a high concentration of non-performing mortgages in financial institutions’ portfolios (López and Rodríguez Citation2011). Debt management policies relied on strong state intervention through the development of a new financial architecture (Vives-Miró Citation2018). Initially, the Fund for Orderly Bank Restructuring was established to stabilize the banking sector (Gutiérrez and Domènech Citation2017), followed by the formation of an asset management company, the SAREB, with primary responsibility to sanitize banks’ spreadsheets by acquiring assets, and re-introduce them in the market as new rental products. These distressed portfolios, alongside socially-protected housing units (Vivienda de Protección Oficial-VPO in Spanish), were sold by 2013 to international financial investors (Janoschka Citation2015). Furthermore, specific reforms absorbed investment risks for financial investors. For example, the amended 2012 Law on Real Estate Investment Trusts (SOCIMI), tendered zero corporate taxation (Gutiérrez and Domènech Citation2017; Janoschka et al. Citation2020); and the 2013 amendment to the Urban Rent Law reduced lease duration to three years (García-Lamarca Citation2021; Janoschka et al. Citation2020). Although this law was revised in 2019 to ensure a minimum five-year tenancy, it had already established a system of different velocities of tenant turnover.

Institutional investors’ activities in the housing market resulted initially in evictions for mortgage defaulted homeowners and progressively into rent increases for tenants (Janoschka et al. Citation2020). With a dynamic discourse, housing activists in Barcelona have been advocating for the rehousing of evicted people in social housing, the occupation of vacant and foreclosed assets owned by transnational investors, and rent negotiations to prevent evictions and homelessness. It has been claimed that the PAH successfully transformed the lived experience of eviction into emancipatory struggles for the right to housing (García‐Lamarca and Kaika Citation2016). Additionally, since 2016 the Tenant’s Union (known in Catalan as Sindicat de Llogateres) has acted as legitimate intermediary between tenants and financial landlords, aiming to prevent evictions and rent increases.

Upon assuming office in 2015, the new municipal government proposed an alternative vision to financial speculation, by placing the social function of housing as a focal point for policy action (Barcelona City Council Citation2019). In this regard, housing provision for citizens was prioritized, and private properties were destined to serve productively the common good, that is via eluding speculation or other uses that impeded access to housing (see Santos and Ribeiro Citation2022). In this endeavour, the municipality relied firstly on the Catalan Law on the Right to Housing (Law 18/2007), which had laid the ground for policies against housing market discrimination, as well as on the central state Law 24/2015 on housing emergency and energy poverty. It should be noted that housing policies in Spain operate between the national and the regional state scales (interview, policy maker, 26/10/2019). Regional states are primarily responsible for implementing housing plans, while the central government retains significant cross-cutting competencies that influence housing, such as state plans for access to housing, allocation of public budgets, and regulation of the credit sector. Housing policies do not fall within the jurisdiction of the local state (Janoschka and Mota Citation2021). However, Article 85 of the Municipal Charter of Barcelona outlines that the planning, programming and management of public housing, correspond exclusively to the Consortium of Housing, in which the regional state (the Generalitat) has 60% of the votes and the City Council 40%, which opens up space for the development of housing policies at the local level. Nonetheless, specific historical and economic reasons have favoured homeownership as a strategic policy for housing provision, limiting the capacity of the local state to intervene in housing markets (Arbaci Citation2019).

The primary municipal goal was to tackle real-estate speculation and related housing vulnerability. However, the lack of statistical data regarding housing (such as vacancy rates, unlicensed short-term rentals, household demographics, number of evictions) compromised policy action. Therefore, initial efforts were directed towards the collection of primary data through surveys, public discussions, and interviews with civic society organizations and civil employees. Command of housing data was deemed crucial for the development of a comprehensive understanding of the housing market’s present condition and dynamics. This served as a basis to guide regulators in formulating precise and effective policies, thereby repositioning the local state as a significant actor in housing market arrangements.

Considering that by 2015 the VPO stock was around 7,500 units and comprised less than 1.5% of total housing, the municipality placed emphasis on expanding the housing stock owned or controlled by the local state to service vulnerable households. Policy innovation relied on the integration of the right of first refusal and the inclusionary planning principle. By asserting the right of first refusal, the municipality acquired priority as the preferred buyer for land and housing in real estate transactions. For example, in 2019 alone, this scheme facilitated the acquisition of over 700 properties, which were subsequently reintroduced into the market as affordable social housing for rent. Moreover, through the implementation of the inclusionary planning principle, the municipality stipulated that 30% of the housing units in new construction projects were to be designated at affordable rents. Additionally, a task force was established to enforce housing’s social function, imposing fines of up to €900,000 for property harassment, vacant flats, or the misuse of VPO housing.

Further strategic initiatives involved the construction of new housing units destined for rent at affordable rates. This was based on leasing of public land to cooperatives and third parties; financially it was supported by a total investment of €560 million; with one-third (€174 million) stemming from European Funding (EIB and CEB loans in 2019) to counterbalance national budget cuts. Moreover, the municipality launched the “Key is in your hands” programme, which invited property owners to enrol their homes in the Barcelona City Council’s housing pool. The government certified punctual rent payment contributions, provided that property owners agreed to predetermined rent levels for vulnerable households. Concurrently, rent subsidies assisted vulnerable families in fulfilling their rent obligations without accumulating arrears.

Over the course of the last eight years, the public housing stock has expanded by 4,100 units. Among these, 1,500 were newly constructed, 1,600 were obtained or transferred through the right of first refusal from financial institutions; 1,000 were sourced from private individuals for rental purposes, and an additional 600 were expected to be completed by the end of 2023. As of 2023, 1,900 units are in progress, and an additional 2,100 are in the pipeline. While in nominal terms these figures may seem insignificant, given the scarcity in VPO, the ongoing expansion of the housing stock managed or controlled by the municipality, indicates a resurgence of the state in housing provision. Presently, the city has significantly surpassed the availability of social housing in comparison to other Spanish cities. This underscores the ability of the municipal government to restore its capacity to intervene in the market with terms for negotiating affordability pressures.

Considering the city’s exposure to international tourist flows and short-term rental proliferation at the expense of housing, specific measures were introduced to counter housing shortages and escalating rents. In 2016, unlicensed tourist apartments were banned, and the municipality obliged Airbnb that listings are registered and conform to city regulations, prohibiting rentals of less than 31 days. Short-term rental operators were compelled to collect tourist taxes for remittance to the city, besides contributing taxes on rental earnings. Furthermore, in 2017, the Special Tourist Accommodation Plan (Peuat) was established, which blocked new hotels and tourist apartments in areas designated as impacted by tourism. By the its first mandate in 2019, the municipality had closed down nearly 5000 illicit tourist apartments, thereby enabling the recovery of over a thousand apartments for private housing use (Crónica Citation2019).

Despite the establishment of such novel measures, numerous households remain susceptible to rent increases and eviction proceedings. Often unable to secure accommodation in municipally-managed or other privately-rented housing, many households are confronted with the risk of social exclusion, potentially resorting to squatting, or are exposed to substandard living conditions. To alleviate the social impact, since 2016 the municipality has formed special units, the Service for Intervention in Situations of Housing Loss and Occupation (SIPHO), that mediate between tenants and landlords, and identify mutually beneficial solutions that enable households to remain in their homes. Furthermore, SIPHO connects vulnerable households with social services to access state benefits that support them in meeting their rent obligations, hence guaranteeing investors’ profitability margins, as discussed by Bernt, Colini, and Förste Citation2017. The SIPHO service has assisted 13,438 households since its inception, preventing 90% of eviction orders (Collel Citation2023).

It is noteworthy that financial investors display greater willingness to engage in such negotiations than individual landlords. With the aim of minimizing investment risk, they seem open to policy innovation:

the bigger actors they are and the longer they intend to stay in the market, the more they develop skills in managing homes and dialogue with the Administration. We have a very good relationship with [name of REITs], they have our telephone numbers, we have theirs, we talk to each other. Their corporate responsibility section and our housing emergency team are in permanent contact.

Prior to the change in local government, investors rarely engaged in discussions regarding eviction procedures. By 2019, most prominent REITs had established communication channels with both the municipality and the Tenants’ Union, to explore solutions for families unable to cope with rent increases. This shift in investors’ behaviour towards negotiating housing vulnerability highlights the local government’s capacity to negotiate new norms for an inclusive dialogue among housing actors regarding the social function of housing.

To further safeguard those experiencing housing vulnerability, in 2020 the Regional Government in Catalonia enacted a rent freeze Law, stipulating that new leases cannot exceed the regionally published price index. The law was adopted by several Catalan municipalities experiencing affordability pressures, including Barcelona, to curb rental increases. Although it was overturned by the Spanish Constitutional Court in 2021, it contributed to a progressive change in national housing policies. A year later, Royal Decree 42/2022 recognized the right to housing as a central pillar of the welfare state. This highlights how policy innovation on housing vulnerability has influenced housing policies across state scales. As regulatory processes define shifts in financial investors’ behaviours, the next section explores institutional investors’ engagement with housing vulnerability.

Corporate Social Responsibility, or Housing Financialization Reloaded?

Financial investors entered the housing market of Barcelona after acquiring NPL portfolios from regional banks, notably Catalunya Caixa, and other financial entities, such as the SAREB. Moreover, in the aftermath of the 2007 financial crisis, Catalan families active in industrial sectors, acquired assets at below market price, and redirected their economic activities towards real estate. In a similar vein, after the moratorium on tourist accommodation, hospitality actors shifted their activities into long- and medium-term rentals. Currently, eighteen residential REITs in Barcelona are registered at the Spanish Stock Exchange. The main shareholders comprise US institutional investors, alongside companies and individual investors from France, Spain and Israel. Notably, SAREB emerges as a significant investor through the REIT Tempore (see ). REITs with national companies or individual investors as majority shareholders are controlling assets which are mainly located in the city centre, while assets stemming from foreclosures, controlled by institutional investors, are traced in the city’s periphery (see also García-Lamarca Citation2021; Gutiérrez and Domènech Citation2017).

Table 2. Residential REITs in Barcelona.

As detailed in interviews with REITs directors, investors in Barcelona predominantly utilize online platforms to display properties and establish direct communication with clients. Potential tenants are required to provide a comprehensive set of personal and financial data, consisting of payslips, historical rental data, and insolvency records. Data are then assessed via an algorithm, which evaluates tenant profiles in relation to market conditions, such as property valuations, rent fluctuations, and the acceptable risk threshold outlined by the company for each individual tenant. While the use of algorithms is presented as a value-neutral method of data analysis, it enables investors to de-risk investments as they predetermine the criteria for access to housing. Moreover, data collection strategies result in continuous monitoring of tenant profiles that mitigates the potential for rent default, and hence the investment risk, but also reinforces an advantageous position of investors in the housing market. Additionally, operating real-estate transactions through online platforms curtails operational costs, particularly those linked to the resources needed for in-person interactions, such as those requiring real estate agents.

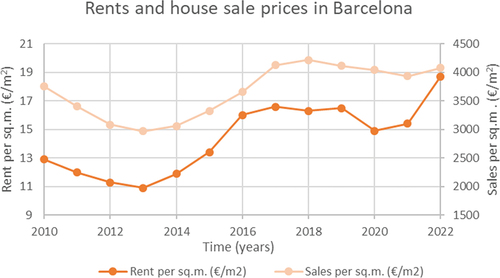

Data shows that between 2013 and 2022, rents in Barcelona witnessed a significant increase, rising from under €12 per m2 to €18.7 per m2 (Idealista Citation2023). This upward trend was temporarily halted in 2020 and 2021, due to the implementation of the rent freeze law. However, following its revocation in 2022, rents began to increase again (see above). Our mapping exerciseFootnote3 shows that neighbourhoods where REIT-owned properties are located, have seen rent increases exceeding 65% since 2013, especially in inner city areas such as Ciutat Vella and Sarrià-Sant Gervasi, as well as on the city periphery, such as in L’Hospitalet de Llobregat (, Map).

Figure 1. Rents and house sale prices in Barcelona 2013-2022.

Figure 2. Map: rent increases in neighbourhoods where properties managed by REITs are located.

One might suggest that, given the documented rent increase, financial investors have persistently adhered to their modus operandi despite the shift in local government. However, our research findings offer a more nuanced approach by focusing attention on the way the most prominent institutional investors have interpreted policy innovation regarding housing vulnerability. As stipulated by Law 24/2015, and fully embraced by the Catalan government, large-scale property owners (possessing more than 10 assets spanning an area exceeding 1.500 m2) must offer social rent contracts to tenants who meet predefined vulnerability criteria and find themselves financially constrained to pay the rent. This legislative framework, coupled with new municipal housing policies, introduces legal risks for investors. As explained:

It is very difficult to manage this risk [referring to rent defaults and squatted assets] because the laws in Catalunya are all about protecting and legalising squats. The administration does not have the capacity to produce social housing and the solution they found is that investors donate assets […] This goes against the principles of a privately rented housing market: if as a fund I invest in this market […] I rent an asset and the asset is occupied or the tenant is not paying the rent, and I have to offer a contract on the basis of the 24/2015 legislation or the 4/2016 law that is the legislation that does not allow evictions for non-payment because of vulnerability […] and now there is a new legislation for a housing squat that existing tenants by July 2019 can stay in the house with a social contract […] there is high juridical risk as they constantly change the regulatory framework […] constitutionally the right to property in Spain is of high value, but what public authorities do here is the expropriation of the property of financial investors.

Financial investors have discerned the economic risks that relate to occupied properties or those accruing unpaid rents, as these assets cease to generate rental income. At the same time, they are aware of the political risks associated with regulations that attach properties to social rent and obscure profitability margins. In many cases, the prolonged legal proceedingsFootnote4 discourage investors from pursuing eviction orders. To mitigate the impact on their portfolios, most prominent REITs in the city have established dedicated corporate social responsibility sections that are in constant communication with the local government and housing campaigners. Moreover, since 2016, partnership projects have been established with third-sector companies that aim to restore tenants’ social and employment status within the framework of corporate social responsibility. This strategy is based on recognizing that households experiencing rent arrears lack the financial resources to fulfil rent obligations due to labour precarity. A fundamental prerequisite for participation in these socio-labour programmes is a new tenancy agreement amongst involved parties. In situations where households face mortgage arrears, they lose property ownership, but they are offered a tenancy lease. For tenants in rental arrears or squatted assets, a preliminary lease agreement offers a social rent, contingent on tenants’ participation in job placement programmes. Upon joining these programmes, households receive tailored support, such as access to digital devices, internet services, or guidance on curriculum structuring, until their reintegration in the local labour market. Once this succeeds, the tenancy agreement is updated, though with a revised rent set at 30% of the newly-acquired income.

Corporate social responsibility initiatives help to de-risk investments in times of progressive housing policies, but also bestow tangible and intangible financial advantages. As discussed in the interviews, the development of socio-labour projects contributes to: (i) the economic recovery of assets, as those previously labelled as dormant or non-productive due to non-contributing tenants start to generate rents; (ii) diminished likelihood of rent defaults, given that rent is guaranteed by the tenant’s stable income from labour; (iii) the restoration of the public image of the investor company, since investors’ economic activities encompass social criteria and alleviate housing vulnerability; and (iv) a social justification of rent increases.

Affiliating the label of social responsibility to the economic activities of financial housing investors is of paramount significance. Mediation procedures with administrative units are marketed under the frame of corporate social responsibility and negotiations with housing campaigners have the potential to avoid protests that attract media attention. This behaviour, besides waiving the bad reputation which was attached to investors after housing repossessions, proves equally important in tenders for land development projects. A prerequisite for prospective bidders is commitment to social corporate responsibility. Therefore, the demonstration of this commitment through housing-related socio-labour projects grants priority to financial investors during the tender process (interview with third sector company director, 02/12/2020).

A housing investor reported having tendered 3,000 social contracts of this kind, boasting a 78% success rate in tenant job placement programmes (interview, REIT real-estate director 01/07/2020). This is branded as a private housing policy initiative that addresses housing vulnerability and employment instability with more concrete results than relevant housing or labour policies (interview, REIT operation manager 30/10/2019). Nevertheless, corporate social responsibility represents a managerial strategy that integrates social, or even environmental, concerns into business practices with a key emphasis on mitigating risks. Such schemes are instrumental in diminishing the societal repercussions of economic activities; while in the context of housing, they help to restore rent revenue streams, thus attaching a kind of political legitimacy to investors with so-called social intentions. In the context of Barcelona, the attachment of social corporate responsibility to business plans epitomizes the investors’ capacity to adapt to the new norms over the social function of housing, while underscoring financial innovation.

Concluding Discussion

Academic discourses have focused on the state as a key actor in the financialization of housing for its regulatory capacity to set an institutional framework that de-risks investments and facilitates financial activities in local residential real-estate markets (Aalbers et al. Citation2023; Çelik Citation2021; Fields Citation2018). Stemming from these reflections, this research opens novel pathways for conceptualizing the interplay of power relations in the financialization of housing by suggesting that actors mutually influence one another and change stance in their strategies in relation to each other. By driving attention to the nature of the state as a social relation, it is demonstrated that regulations are equally influenced by housing struggles and social claims on vulnerability and affordability; while at the same time, progressive policies and social mobilizations prompt investors to take into consideration local circumstances. In cases where the regulatory framework is not favourable to financial interests, rather than circumventing or pushing policies to their advantage, institutional investors respond to social policy innovation by adjusting business plans to the current conditions. This approach facilitates a dynamic understanding of the process where actors constantly redefine power relations in housing affairs, prompting shifts in the financialization of housing.

Specifically, by driving attention to the way social claims of the right to housing have penetrated policy discourse and upscaled into regulations that cater for housing vulnerability, this research redirects the academic discourse on post-neoliberal housing policies to definancialize housing towards a systematic understanding of the state as a social relation, which is continuously shaped under the influence of social and political events. Even within the context of a dualist rental system where the state has limited capacity for market intervention, local governments can incite new norms in negotiating access to housing. This reinstates the state as a social provider in housing affairs.

Academic discourses illustrate that investors focus on maintaining a permanent flow of rents through operational cost reduction, efficiency gains, market expansion and rent increase strategies (Holm, Alexandri, and Bernt Citation2023; Wijburg, Aalbers, and Heeg Citation2018). Our findings contribute to broadening and deepening this understanding by revealing the income generating capacities from corporate social projects which are launched in the name of social responsibility. Additionally, the timing of such projects is interrogated, as social responsibility as a strategy was adopted after the change in the institutional framework that situated the social function of housing as the new norm. As progressive housing policies in Barcelona were held responsible for economic risks, financial investors were triggered to better evaluate novel regulations, engage actively with new policy norms and reposition themselves as legitimate and socially-sensitive housing providers. However, as we have shown, the development of socio-labour projects outlines the way investors engage entrepreneurially with social vulnerability. The incorporation of social corporate responsibility agendas in business plans helps to diminish reputational risks, and restore rent revenue streams from assets that were classified as “non-active”, thus rationalizing rent increases under the banner of assisting tenants to counteract labour causality. This kind of financial innovation not only de-risks investments, but also maintains financial operations and profitability margins intact.

Savini (Citation2017) suggests that economic risks have the potential to spur entrepreneurial and experimental initiatives to investors, while fostering a sense of responsibility for social and political engagement. The recent tendency amongst key institutional housing investors to integrate Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria in business plans as a de-risking strategy is of paramount importance. As social risks, on top of environmental risks, pose threats to the successful delivery or maintenance of investment products, ESG criteria empower investors to navigate future structural uncertainties. Additionally, this strategy facilitates participation in emerging financial markets, such as social and climate-change bonds, thereby optimizing potential capital returns. This research has enabled a step change towards a comprehensive understanding of the way in which financial and policy innovations are geared in a world characterized by escalating levels of social, environmental, and political risks. What is more, such risks potentially herald a new stage in housing financialization research.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to all the participants and informants who generously dedicated their time to this research and to Katerina Bartsoka for the map elaboration. Moreover, Georgia would like to extend a special note of appreciation to Melissa García-Lamarca and Brian Rosa. Their kindness and support created a safe, welcoming and warm environment for her during field research in Barcelona. Therefore, their contribution was invaluable and deeply appreciated.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Sociedades Anónimas Cotizadas de Inversión Inmobiliaria.

2. 2013 was chosen as year of reference as foreclosed assets and social housing passed to the ownership of financial investors.

3. Consisting of properties made publicly available in REIT’s Annual Reports. This was not possible for properties managed by Blackstone, as asset direction is not available.

4. Due to administration coordination between juridical bodies and the police, an eviction process may last several years.

References

- Aalbers, M. 2016. The Financialization of Housing. New York: Routledge.

- Aalbers, M. B., Z. J. Taylor, T. J. Klinge, and R. Fernandez. 2023. “In Real Estate Investment We Trust: State de-Risking and the Ownership of Listed US and German Residential Real Estate Investment Trusts.” Economic Geography 99 (3): 312–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2022.2155134.

- Adkins, L., M. Cooper, and M. Konings. 2021. “Class in the 21st Century: Asset Inflation and the New Logic of Inequality.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 53 (3): 548–572. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X19873673.

- Alexandri, G. 2022. “Housing financialization a la Griega.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 136:68–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2022.07.014.

- Alexandri, G., and M. Janoschka. 2018. “Who Loses and Who Wins in a Housing Crisis? Lessons from Spain and Greece for a Nuanced Understanding of Dispossession.” Housing Policy Debate 28 (1): 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2017.1324891.

- Arbaci, S. 2019. Paradoxes of Segregation: Housing Systems, Welfare Regimes and Ethnic Residential Change in Southern European cities. Oxford: John Wiley and Sons.

- Barcelona City Council. 2019. Innovation in Affordable Housing Barcelona 2015-2019. Barcelona: Barcelona City Council.

- Belotti, E., and S. Arbaci. 2021. “From Right to Good, and to Asset: The State-Led Financialization of the Social Rented Housing in Italy.” Environment & Planning C Politics & Space 39 (2): 414–433. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654420941517.

- Bernt, M., L. Colini, and D. Förste. 2017. “Privatization, Financialization and State Restructuring in Eastern Germany: The Case of Am Südpark.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 41 (4): 555–571. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12521.

- Beswick, J., and J. Penny. 2018. “Demolishing the Present to Sell off the Future? The Emergence of ‘Financialized Municipal entrepreneurialism’ in London.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 42 (4): 612–632. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12612.

- Bianchi, I. 2023. “The Commonification of the Public Under New Municipalism: Commons–State Institutions in Naples and Barcelona.” Urban Studies 60 (11): 2116–2132. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980221101460.

- Birch, K., and F. Muniesa. 2020. Assetization: Turning Things into Assets in Technoscientific Capitalism. Cambridge: The MIT press.

- Blanco, I. 2015. “Between Democratic Network Governance and Neoliberalism: A Regime-Theoretical Analysis of Collaboration in Barcelona.” Cities 44:123–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2014.10.007.

- Blanco, I., Y. Salazar, and I. Bianchi. 2020. “Urban Governance and Political Change Under a Radical Left Government: The Case of Barcelona.” Journal of Urban Affairs 42 (1): 18–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2018.1559648.

- Brenner, N. 1999. “Globalisation As Reterritorialisation: The Re-Scaling of Urban Governance in the European Union.” Urban Studies 36 (3): 431–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098993466.

- Byrne, M. 2016. “Bad Banks and the Urban Political Economy of Financialization: The Resolution of Financial–Real Estate Crises and the Co-Constitution of Urban Space and Finance.” City 20 (5): 685–699. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2016.1224480.

- Çelik, Ö. 2021. “The Roles of the State in the Financialization of Housing in Turkey.” Housing Studies 38 (6): 1006–1026. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2021.1928003.

- Charnock, G., T. F. Purcell, and R. Ribera‐Fumaz. 2014. “City of Rents: The Limits to the Barcelona Model of Urban Competitiveness.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 38 (1): 198–217. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12103.

- Cochrane, A. 2007. Understanding Urban Policy: A Critical Approach. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Colau, A., and A. Alemany. 2014. Mortgaged Lives. Los Angeles: Journal of Aesthetics & Protest.

- Collel, 2023. “El gobierno de Colau ha aumentado un 53% la vivienda pública de Barcelona pero aloja un 70% más en pensiones”. El Periódico. Accessed August 05, 2023. https://www.elperiodico.com/es/barcelona/20230403/gobierno-colau-aumentado-53-vivienda-85573461.

- Coq‐Huelva, D. 2013. “Urbanisation and Financialization in the Context of a Rescaling State: The Case of Spain.” Antipode 45 (5): 1213–1231. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12011.

- Crónica, 2019. “Colau ha cerrado 4.900 pisos turísticos desde 2016.” Crónica Global. Accessed August 10, 2023. https://cronicaglobal.elespanol.com/politica/20190302/colau-ha-cerrado-pisos-turisticos-desde/380211976_0.html.

- Featherstone, D., K. Strauss, and D. MacKinnon. 2015. “In, Against and Beyond Neo-Liberalism: The “Crisis” and Alternative Political Futures.” Space and Polity 19 (1): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562576.2015.1007695.

- Ferm, J., and M. Raco. 2020. “Viability Planning, Value Capture and the Geographies of Market-Led Planning Reform in England.” Planning Theory and Practice 21 (2): 218–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2020.1754446.

- Fields, D. 2018. “Constructing a New Asset Class: Property-Led Financial Accumulation After the Crisis.” Economic Geography 94 (2): 118–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2017.1397492.

- Fuller, G. W. 2021. “The Financialization of Rented Homes: Continuity and Change in Housing Financialization.” Review of Evolutionary Political Economy 2:551–570. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43253-021-00050-7.

- Gabor, D., and S. Kohl. 2022. My Home Is an Asset Class. The Financialization of Housing in Europe. Brussels: The Greens/EFA.

- García‐Lamarca, M., and M. Kaika. 2016. “‘Mortgaged lives’: The Biopolitics of Debt and Housing Financialization.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 41 (3): 313–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12126.

- García-Lamarca, M. 2021. “Real Estate Crisis Resolution Regimes and Residential REITs: Emerging Socio-Spatial Impacts in Barcelona.” Housing Studies 36 (9): 1407–1426. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2020.1769034.

- Gotham, K. F. 2009. “Creating Liquidity Out of Spatial Fixity: The Secondary Circuit of Capital and the Subprime Mortgage Crisis.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 33 (2): 355–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2009.00874.x.

- Gutiérrez, A., and A. Domènech. 2017. “Geografía de los desahucios por ejecución hipotecaria en las ciudades españolas: evidencias a partir de las viviendas propiedad de la SAREB.” Revista de geografía Norte Grande 67 (67): 33–52. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-34022017000200003.

- Haffner, M. E., and K. Hulse. 2021. “A Fresh Look at Contemporary Perspectives on Urban Housing Affordability.” International Journal of Urban Sciences 25 (1): 59–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/12265934.2019.1687320.

- Hochstenbach, C., and R. Ronald. 2020. “The Unlikely Revival of Private Renting in Amsterdam: Re-Regulating a Regulated Housing Market.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 52 (8): 1622–1642. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518x20913015.

- Holm, A., G. Alexandri, and M. Bernt 2023. “Housing Policy Under the Condition of Housing Financialization: The Impact of Institutional Investors on Affordable Housing in European Cities.” Paris: SciencePo. https://www.sciencespo.fr/ecole-urbaine/sites/sciencespo.fr.ecole-urbaine/files/Rapporthousinghopofin.pdf.

- Idealista, 2023. Historic Rent Values in Barcelona per Neighbourhood. Accessed August 20, 2023. https://www.idealista.com.

- Janoschka, M. 2015. “Politics, Citizenship and Disobedience in the City of Crisis: A Critical Analysis of Contemporary Housing Struggles in Madrid.” DIE ERDE–Journal of the Geographical Society of Berlin 146 (2–3): 100–112. https://doi.org/10.12854/erde-146-9.

- Janoschka, M., G. Alexandri, H. O. Ramos, and S. Vives-Miró. 2020. “Tracing the Socio-Spatial Logics of Transnational landlords’ Real Estate Investment: Blackstone in Madrid.” European Urban and Regional Studies 27 (2): 125–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776418822061.

- Janoschka, M., and F. Mota. 2021. “New Municipalism in Action or Urban Neoliberalisation Reloaded? An Analysis of Governance Change, Stability and Path Dependence in Madrid (2015–2019).” Urban Studies 58 (13): 2814–2830. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020925345.

- Jessop, B. 1990. State Theory: Putting the Capitalist State in Its Place. Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Kadi, J., L. Vollmer, and S. Stein. 2021. “Post-Neoliberal Housing Policy? Disentangling Recent Reforms in New York, Berlin and Vienna.” European Urban and Regional Studies 28 (4): 353–374. https://doi.org/10.1177/09697764211003626.

- Karwowski, E. 2019. “Towards (de-) Financialization: The Role of the State.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 43 (4): 1001–1027. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bez023.

- Kettunen, H., and H. Ruonavaara. 2021. “Rent Regulation in 21st Century Europe. Comparative Perspectives.” Housing Studies 36 (9): 1446–1468. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2020.1769564.

- Lapavitsas, C. 2014. Profiting without Producing: How Finance Exploits Us All. London: Verso.

- López, I., and E. Rodríguez. 2011. “The Spanish Model.” New Left Review 69 (3): 5–29.

- Musil, R., F. Brand, and S. Punz. 2022. “The Commodification of a Rent-Regulated Housing Market. Actors and Strategies in Viennese Neighbourhoods.” Housing Studies 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2022.2149707.

- Nethercote, M. 2020. “Build-To-Rent and the Financialization of Rental Housing: Future Research Directions.” Housing Studies 35 (5): 839–874. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2019.1636938.

- Palomera, J. 2014. “How Did Finance Capital Infiltrate the World of the Urban Poor? Homeownership and Social Fragmentation in a Spanish Neighbourhood.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 38 (1): 218–235. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12055.

- Peck, J., N. Brenner, and N. Theodore. 2018. ”Actually Existing Neoliberalism.” In The Sage Handbook of Neoliberalism, edited by C. Damien , C. Melinda , K. Martin, and P. David, 3–15. London: Sage.

- Russell, B. 2019. “Beyond the Local Trap: New Municipalism and the Rise of the Fearless Cities.” Antipode 51 (3): 989–1010. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12520.

- Santos, A. C., and R. Ribeiro. 2022. “Bringing the Concept of Property As a Social Function into the Housing Debate: The Case of Portugal.” Housing Theory & Society 39 (4): 464–483. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2021.1998218.

- Savini, F. 2017. “Planning, Uncertainty and Risk: The Neoliberal Logics of Amsterdam Urbanism.” Environment and Planning A 49 (4): 857–875. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X16684520.

- Taşan-Kok, T., and S. Özogul. 2021. “Fragmented Governance Architectures Underlying Residential Property Production in Amsterdam.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 53 (6): 1314–1330. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X21996351.

- Thompson, M. 2021. “What’s so New About New Municipalism?” Progress in Human Geography 45 (2): 317–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132520909480.

- Uitermark, J., C. Hochstenbach, and J. Groot. 2023. “neoliberalization and Urban Redevelopment: The Impact of Public Policy on Multiple Dimensions of Spatial inequality.” Urban Geography 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2023.2203583.

- United Nations. 2017. ““Report of the Special Rapporteur on Adequate Housing” UN Document Number A/HRC/34/52.” Accessed September 15, 2020. https://www.undocs.org.

- Van Loon, J., S. Oosterlynck, and M. B. Aalbers. 2019. “Governing Urban Development in the Low Countries: From Managerialism to Entrepreneurialism and Financialization.” European Urban and Regional Studies 26 (4): 400–418. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776418798673.

- Vives-Miró, S. 2018. “New Rent Seeking Strategies in Housing in Spain After the Bubble Burst.” European Planning Studies 26 (10): 1920–1938. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2018.1515180.

- Ward, K. 2017. “Financialization and Urban Politics: Expanding the Optic.” Urban Geography 38 (1): 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2016.1248880.

- Weber, R. 2015. From Boom to Bubble: How Finance Built the New Chicago. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Wijburg, G. 2019. “Reasserting State Power by Remaking Markets? The Introduction of Real Estate Investment Trusts in France and Its Implications for State-Finance Relations in the Greater Paris Region.” Geoforum 100:209–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.01.012.

- Wijburg, G. 2021. “The de-Financialization of Housing: Towards a Research Agenda.” Housing Studies 36 (8): 1276–1293. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2020.1762847.

- Wijburg, G., M. B. Aalbers, and S. Heeg. 2018. “The Financialization of Rental Housing 2.0: Releasing Housing into the Privatised Mainstream of Capital Accumulation.” Antipode 50 (4): 1098–1119. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12382.