ABSTRACT

Anglophone countries are diversifying their responses to housing insecurity, decentring social housing and expanding use of market-oriented assistance that aims to promote “housing independence” . Drawing on fieldwork in three Australian jurisdictions, this paper examines the impact of this shift for how housing assistance is allocated. We argue that allocations practices can no longer be understood as centred on the rationing of a single product – social housing. Rather, they nowadays perform a “social sorting” function that mimics those developed in consumer marketing, where personal information is collected to classify and segment consumers to match them to tailored “products”. These practices sort households based on their “capacity for independence”, aiming to maximize market engagement and reserving social housing for those with the most complex needs. We conclude that these sorting practices ignore both the realities of private renting in Australia (as elsewhere) and the self-defined housing needs of low-income households.

Introduction

There is a long term shift underway in how Anglophone countries are addressing housing insecurity, understood as “the loss of, threat to, or uncertainty of a safe, stable, and affordable home environment” (DeLuca and Rosen Citation2022, 344). This shift involves the decentring of de-commodified public or social housingFootnote1 by a variety of measures that work through private markets, engendering a more diversified response to housing insecurity. These market-based measures include new forms of “affordable rental” accommodation where private and non-profit providers are incentivized to provide housing at modestly discounted rents, and financial and/or practical assistance aimed at supporting households to access private rental housing (e.g. rental grants or subsidies) (Blessing Citation2016; Colburn Citation2021). Such measures enrol private actors in the provision of housing to vulnerable low-income households, blurring the boundaries between the public/private distinction that structured housing systems for much of the post-war period (Blessing Citation2016; Humphry Citation2020). They also constitute a shift from the more universalist social welfarist objective of ensuring the housing needs of all are met to the neoliberal aim of promoting “economic opportunity” and “independence” by encouraging market engagement as a pathway to social mobility (Blessing Citation2016).

These developments reflect the changing governmentality of housing insecurity in the Anglophone world, where “governmentality” refers to how problems like housing insecurity are conceptualized and addressed, and the forms of knowledge and practical intervention that shape this (Foucault Citation2007; Miller and Rose Citation2008). Specifically, it reflects the ongoing transformations brought about by neoliberal governmentality, which reorients housing policy from addressing unmet need to underwriting housing markets, promoting “entrepreneurial” capacities/dispositions, and limiting dependence on the state (Blessing Citation2016; Clarke, Cheshire, and Parsell Citation2020; Cowan and McDermont Citation2006; Jacobs Citation2019).

This paper examines the implications of this changing governmentality for how people experiencing housing insecurity are assessed and allocated housing assistance, whether this be financial or in-kind support (herein “assistance allocations”). Existing research has portrayed assistance allocations as dominated by rationing imperatives (e.g. Clapham and Kintrea Citation1986; Lidstone Citation1994; Moore Citation2016). In contrast to market transactions where resources are allocated through the price mechanism, housing assistance is typically allocated via administrative practices that selectively disburse available resources in the face of often overwhelming demand (Hulse and Burke Citation2005). The presence of rationing imperatives is particularly clear in studies focused on individual/discrete forms of assistance, including social housing tenancies (Clapham and Kintrea Citation1986; Hulse and Burke Citation2005; Morris et al. Citation2022) or rental subsidy/voucher schemes (Moore Citation2016; Zhang and Johnson Citation2023). But what happens in the contemporary neoliberal context where housing authorities are administering multiple forms of assistance simultaneously? Our argument is that, here, assistance allocations do more than ration housing resources. They also sort people for different kinds of assistance outcomes based on assessment of their capacity for “market independence”.

We demonstrate these claims using research conducted in three Australian jurisdictions: New South Wales (NSW), Queensland, and Tasmania. Reflecting a direction of travel common across many comparator countries, recent decades have seen all three states diversifying housing help for needy citizens by expanding private rental assistance (PRA). This, in turn, has shifted how households seeking support are assessed and allocated resources. Our findings show that assistance allocations now perform complex “social sorting” functions that are underpinned by consumerist principles and not reducible to rationing imperatives (Lyon Citation2003). Housing authorities cast themselves as providing a suite of assistance “products” tailored to the diverse needs of their “customers”. Assistance allocations are therefore oriented to classifying applicants’ needs and matching them with the most appropriate assistance products. Informed by judgements about households’ capacity for independence, these channel those with greater capacity towards forms of PRA and those with lesser capacity to social housing. These judgements are supported by new automated decision-making (ADM) tools, such digital databases and computer algorithms, paralleling business practice developments in the private rental sector (Ferreri and Sanyal Citation2022; Fields and Rogers Citation2021).

We begin by reviewing the literature on assistance allocations, highlighting the historic centrality of the rationing lens, then describing the diversification of housing assistance and introducing “social sorting” as an alternative conceptualization. After outlining our methodology, we present our research findings and then conclude by critiquing key assumptions and claims underpinning contemporary approaches. Here we argue that such approaches ignore both the increasingly unaffordable and insecure nature of private renting in Australia (Morris, Hulse, and Pawson Citation2021), and the self-defined needs of low-income households, for many of whom the security of social housing is prized far above the supposedly wider choice and independence available via private market provision (Flanagan et al. Citation2020).

Housing Assistance Allocations As a Rationing Process

A defining feature of government housing assistance, like most other welfare programmes, is that it is allocated primarily through administrative practices rather than market transactions (Cowan and McDermont Citation2006; Hulse and Burke Citation2005). Research on these practices has largely focused on their role in rationing specific forms of housing assistance, typically social housing tenancies. Since housing assistance programmes involve an unpriced resource (i.e. they are not allocated based on capacity/willingness to pay a market price), rationing is indeed an inherent feature of their administration. In the early post-war period this was exemplified by simple queuing arrangements for social housing allocations (Fitzpatrick and Pawson Citation2007). Since the rise of neo-liberalism in the 1980s, however, social housing has been subject to increasingly intense and complex rationing procedures, as funding cuts and divestment have greatly exacerbated its scarcity in many countries, including Australia, the United Kingdom (UK), and some Western European nations (Jacobs Citation2019; Pawson, Milligan, and Yates Citation2020; Scanlon, Arrigoitia Fernández, and Whitehead Citation2015). While there have also been efforts to enhance consumer choice mechanisms within such processes (Pawson and Hulse Citation2011), these have been highly constrained. Other forms of housing assistance are also shown to be tightly rationed, such as the USA’s Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) scheme, developed to offset social housing divestment/demolitions in that country (Goetz Citation2011), funding for which is only sufficient to support about a quarter of eligible households (Moore Citation2016).

Rationing practices take many forms. Most types of housing assistance have eligibility criteria limiting who can apply, referred to as “primary rationing” (Clapham and Kintrea Citation1991; Burke and Hulse Citation2003). These include income and asset limits, as well as residency requirements such as holding national citizenship and, in some cases, a demonstrable connection to the locality (Fitzpatrick and Stephens Citation1999; Kim Citation2022; Pawson and Lilley Citation2022). Housing assistance is also rationed through prioritization practices determining the order in which eligible applicants are served (“secondary rationing”). This may be based on waiting time or the identification of priority cohorts (e.g. households deemed to have greatest need) (Fitzpatrick and Stephens Citation1999; Moore Citation2016). There is also evidence of housing authorities rationing resources by closing waitlists to new applicants when demand exceeds a certain threshold (Moore Citation2016).

Alongside these more formal practices, research has also highlighted various informal or subtle methods for rationing housing assistance. Informed by the literature on “street level bureaucracy” (e.g. Lipsky Citation1980), studies have shown how frontline housing officers administering scarce resources can employ informal gatekeeping practices – e.g. withholding information on what assistance is available or giving incorrect advice about an applicant’s eligibility for, or likelihood of receiving, assistance (Alden Citation2015; Lidstone Citation1994). Others show how frontline workers are forced to make discretionary decisions on how to ration assistance resources when formal policies are unclear or insufficient to differentiate between applicants with equal priority (Morris et al. Citation2022).

Informal/subtle rationing can also be the unintended consequence or tacit aim of formal policies. Studies describe how housing authorities “purge” assistance waiting lists by requiring approved applicants to complete periodic reviews to test ongoing eligibility (Kim Citation2022; Pawson and Lilley Citation2022; Pawson, Brown, and Jones Citation2009). This not only weeds out applicants whose changed circumstances render them ineligible; it also leads to the removal of applicants failing to engage for other reasons – e.g. where residential instability results in missed correspondence (Kim Citation2022). Other studies describe how “administrative burdens” associated with applying for housing assistance contribute to informal rationing (Keene et al. Citation2023; Morris et al. Citation2023). This includes navigating complex housing bureaucracies and completing onerous application forms, wherein applicants must make their circumstances “legible” (Rita, Garboden, and Darrah-Okike Citation2022) to housing authorities by providing evidence or institutional verification of their eligibility or priority need; for example by providing bank statements, medical records, police reports (for survivors of domestic violence) or a referral from a homelessness service (Morris et al. Citation2023; Rita, Garboden, and Darrah-Okike Citation2022; Zhang and Johnson Citation2023). Such burdens can deter applications, particularly from those with acute vulnerabilities, thereby contributing to resource rationing (Keene et al. Citation2023; Morris et al. Citation2023).

In addition to operating through diverse practices, research shows that rationing is also shaped by a diversity of administrative logics. Reflecting the neo-liberal emphasis on welfare targeting (Jacobs Citation2019), the distribution of intensive/long-term forms of assistance like social housing is nowadays highly prioritized according to “greatest need” (Cowan and McDermont Citation2006; Pawson and Lilley Citation2022; Scanlon, Arrigoitia Fernández, and Whitehead Citation2015). Under these policy settings, social housing is not only restricted to very low-income earners but is also prioritized according to non-income-based vulnerabilities, such as experiences of homelessness, domestic and family violence, disability, or chronic health issues (Rita, Garboden, and Darrah-Okike Citation2022) – or some combination of these (“complex needs”) (Clarke et al. Citation2022) (There is also evidence of rationing of HCVs based on greatest need in larger urban jurisdictions in the USA; Zhang and Johnson Citation2023). Combined with the funding cuts and divestment noted above, this intensified targeting has contributed to the “residualisation” of social housing: its simultaneous shrinking relative to market tenures and the concentration of the most disadvantaged households amongst its tenants (Angel Citation2023; Clarke et al. Citation2022).

The assumption underpinning prioritization of those in greatest need is that they are the most “deserving” of public support, as they are least able to meet their housing needs via the private market. Indeed, people with acute, multiple and/or intersecting vulnerabilities are increasingly recognized as unable to fulfil the neoliberal expectation of individual self-reliance and are thus accepted as having a “legitimate dependence” on intensive forms of state support like social housing (Clarke, Cheshire, and Parsell Citation2020; Rita, Garboden, and Darrah-Okike Citation2022). This suggests something of a reworking of older conceptions of deservingness that eschewed need and instead allocated assistance based on the behaviours and “moral worth” of assistance applicants, such as whether a household is in paid employment or “intentionally homeless” (Fitzpatrick and Pawson Citation2007).

Yet, whilst the focus on greatest need is pervasive, it often exists alongside (and in tension with) allocations logics that resonate with these older, more behavioural conceptions of deservingness. Cowan and McDermont (Citation2006) show how balancing judgements of need against the risk of disruptive or “problem” behaviours has been a recurring theme in UK social housing allocation policies (Cowan and McDermont Citation2006). Studies of more recently emerging models of housing assistance, such as “affordable rental”, show how these prioritize “financially self-reliant” applicants judged better able to cover the higher rents involved and a lower financial risk to housing providers (Humphry Citation2020, 458). Indeed, there is evidence that English not-for-profit housing providers have been increasingly applying minimum (rather than maximum) income thresholds in new tenant selection, perhaps triggered by the UK Government’s “affordable rent” subsidy regimeFootnote2 (Preece and Bimpson Citation2019; Fitzpatrick et al. Citation2019). Similar logics have been identified in private rental assistance subsidy schemes. Zhang and Johnson (Citation2023) show how the performance of US local housing offices is assessed on HCV uptake rates, creating an incentive to prioritize those applicants most attractive to private landlords, such as those with higher incomes and fewer vulnerabilities.

The focus on financial self-reliance is also associated with assessments of applicants’ potential for social mobility. Blessing (Citation2016, 168) reports that affordable rental housing in the USA, UK, and Australia “are promoted as pathways to homeownership and other forms of ‘opportunity’” such as access to employment or university. They therefore tend to favour applicants able to take advantage of these “opportunities”, suggesting that ‘[a]ffordable rental may … be understood as a strategy of “backing winners”, based on the notion of “economic opportunity” rather than charity, or any universal right to housing’ (ibid.). Thus, unlike the focus on greatest needs, neoliberal values of self-reliance/market independence remain influential in the allocation of these forms of assistance.

Diversified Assistance and the Shift to Social Sorting

There is, therefore, a diversity of logics informing rationing practices that map in complicated ways to the diversity of housing assistance measures now offered in many Anglophone states. As noted above, such states have over the last three-to-four decades sought to decentre social housing in the governance of housing insecurity. On the one hand, this entailed slashing expenditure on new, and divestment of existing, social housing dwellings, coupled with the intensified rationing of the dwindling stock that remained through the methods outlined above (Jacobs Citation2019; Pawson, Milligan, and Yates Citation2020). On the other hand, it involved the expansion of alternative forms of housing assistance that work through the market, either by enrolling market actors in the provision of sub-market priced housing or by supporting people to access (market price) private tenancies. These alternative forms of assistance include so-called affordable rental housing products such as those provided through the USA’s Low Income Tax Credit Scheme, the (now defunct) National Rental Affordability Scheme and forthcoming Housing Australia Future Fund in Australia, and the Affordable Homes programme in the UK. These schemes provide incentives to private or non-profit actors – typically through public subsidies or tax concessions – to finance and/or deliver housing to low-to-middle income groups at below market rates – often discounted to market prices by 20–30% (Blessing Citation2016). Alternative assistance also includes “demand side” interventions aimed at supporting people to overcome financial and other barriers to accessing private rental housing (Colburn Citation2021; Pawson and Lilley Citation2022). These often take the form of housing vouchers or subsidies that assist tenants to cover the cost of private rents. Prominent examples include the USA’s Housing Choice Voucher scheme; the UK’s Housing Benefits scheme; and Australia’s Commonwealth Rent Assistance scheme and the various state-level private rental assistance initiatives that are the empirical focus of this paper (Colburn Citation2021; Pawson and Lilley Citation2022; Pawson, Milligan, and Yates Citation2020).

The upshot of these developments is that housing authorities in these jurisdictions now have a suite of assistance measures at their disposal when responding to people seeking support. Our argument in this paper is that this has implications for how housing authorities assess applicants and allocate assistance to them that are not well captured by the concept of “rationing”. Whilst each specific form of assistance may still be rationed, the concept does not fully illuminate how housing authorities determine which form of assistance to allocate to which applicants.

To better capture this process, we dislodge rationing from its central place in the conceptualization of allocations practices and instead treat it as one feature of a broader process of social sorting that defines the allocation of housing assistance today. The term “social sorting” comes from surveillance studies, and whilst it has been applied in various empirical contexts, it has not previously been used to examine the diversification of housing assistance and its impact on how housing assistance is allocated. Social sorting refers to the myriad ways that personal information is used to classify and segment populations for different interventions or outcomes (Lyon Citation2003, 2018). It draws attention to the use of digital databases and computer codes/algorithms in enabling increasingly fine-grained discriminations about populations of interest and more complex sorting operations – a point we take up below. It also reveals how similar sorting practices are deployed for a variety of purposes and contexts, from the rationing of public assistance to the policing of “risky” populations to the stimulation of consumer markets (Eubanks Citation2018; Lyon Citation2003).

This last point is particularly relevant for our argument. Whilst social sorting practices are often used to ration scarce resources – e.g. by prioritizing people based on need/deservingness – they are also used to incite and guide consumption in some contexts. In an age of “post-Fordist” production, where mass-produced goods and services are increasingly replaced by personalized/bespoke offerings, social sorting practices aim to segment consumers based on niche tastes and desires (Lyon Citation2003). This process is taken to the extreme in today’s digitized societies, where masses of consumer data are generated through social media, ecommerce websites, and streaming services (Van Dijck Citation2014). The “big data” generated by these platforms is linked up, sold, and algorithmically sorted to enable ever-more fine-grained consumer targeting of product advertisements.

Whilst the allocation of public assistance has yet to reach this level of sophistication, there are some telling similarities in how governments are approaching their relationship with citizens. Post-1980s public service reforms were premised on the re-envisaging of citizens as consumers/customers whose diverse needs and preference are not well serviced by “one-size-fits-all” bureaucratic modes of provision (Clarke et al. Citation2007; Pawson and Watkins Citation2007). Reforms thus aim for more “personalised” and “customer focused” government services tailored to the (ostensible) needs of citizen-consumers (Clarke et al. Citation2007; Needham Citation2011). This includes adoption of customer relationship management (CRM) systems that compile data about service users to “segment and classify” them and enable personalized service delivery (Richter and Cornford Citation2008, 213). Governments are also looking to emulate private companies by utilizing big data and automated decision making (ADM) tools to facilitate social policy administration more generally (Fey Henman Citation2022) and housing assistance in particular (Eubanks Citation2018; Ferreri and Sanyal Citation2022).

The adoption of these more consumerist modes of social sorting, and their underlying technologies, cannot be separated from the broader market-centrism of contemporary neoliberal social and housing policy. “Liberal” welfare states, such Australia, Canada and the USA, have long sought to limit direct state provision to the residual role of supporting those who “fail in the market” (Esping-Andersen Citation1990, 22). What is distinct about neoliberal approaches, however, is that they go beyond this safety net function to actively facilitate and underwrite market engagement. Indeed, whilst some early conceptualizations of neoliberalism saw it as the “rolling back” of the state, the conceptualizations most influential today recognize that it instead involves a reworking and redeployment of state power and resources in the service of marketization (Foucault Citation2008; Peck and Tickell Citation2002; Wacquant Citation2012). This process is clearly visible in the housing context where reductions in direct assistance (social housing tenancies) have coincided with the expansion of indirect assistance that works through, and underwrites, market engagement (affordable rental, PRA). This process compounds social housing residualisation by underpinning the market engagement of households who might otherwise have resided in such homes.

The pursuit of marketization in housing and social welfare is underpinned by the core neoliberal assumption that market relations are the optimal mode of organizing social life and meeting the needs of individuals and communities. Premised on faith in “active citizens” taking responsibility for the expression and fulfilment of their needs, market engagement is portrayed as a demonstration of independence – a core moral virtue in the neoliberal world view (Miller and Rose Citation2008). State provision, by contrast, is depicted as promoting dependence, an apparently pacifying and morally corrosive state that stifles capacity for personal responsibility and self-fulfilment and is to be avoided in all but the most exceptional circumstances. The redeployment of public assistance to support market engagement thus goes beyond the pursuit of cost savings and efficiencies (as reflected in rationing imperatives) in that it also reflects this – arguably more fundamental – goal of maximizing independence. As we show below, alongside rationing imperatives, aspirations to “promote independence” play a key role in how housing assistance is allocated in Australia.

Methodology

This paper is informed by research on the governance and lived experience of social housing waiting list applicants in Australia, carried out between 2020 and 2023 (REDACTED). Whilst the study initially focused on the governance of access to social housing, early fieldwork observations emphasized the importance of understanding practices and rationales associated with other housing assistance measures, particularly PRA. Our fieldwork therefore expanded to encompass this.

The research focused on three states – New South Wales (NSW), Queensland and Tasmania – selected to reflect the variability of the Australian administrative and demographic landscape. NSW is Australia’s largest state by population (eight million), Queensland is third largest (five million), and Tasmania is the smallest (540,000). Whilst all three jurisdictions have broadly similar policy orientations and oversee similarly residualised social housing sectors, they encompass substantial diversity in settlement geography and housing market conditions. During the 2010s and into the early 2020s, all three states have faced intensifying rental stress and social housing shortfalls. In their socio-economic and housing market contexts, and their governance orientations, the three states are reasonably representative of all Australian jurisdictions. Arguably, in their management of housing assistance they also exemplify orthodox thinking and practice common to comparator countries such as the UK.

We draw here on analysis of policies and processes governing access to housing assistance in the three states. In addition to reviewing relevant policy documents and webpages, this involved 50 semi-structured interviews with key housing policy stakeholders, spanning state housing officials, advocacy and service delivery organizations including non-profit housing providers. Interviewees included a mix of policy, management, and service delivery personnel to encompass a range of perspectives. Fieldwork was undertaken 2020–2022. Interviews lasted 45–120 minutes and were undertaken either face-to-face or via web conferencing software. All interviewees provided informed consent and interview material is de-identified to maintain participant confidentiality. The research received ethical approval from [REDACTED].

Data analysis was informed by a governmentality perspective (Foucault Citation2007; Miller and Rose Citation2008). We examined how policy documents and interviewees rationalized housing insecurity as a policy problem, the housing assistance responses they proposed to address it, and their knowledge of allocating housing assistance in practice. We sought to identify the political rationalities (e.g. neoliberalism), policy discourses (e.g. “housing pathways/continuum”) and governing practices/techniques (e.g. PRA, consumerist social sorting practices) that informed or were drawn upon by policy makers in this process. Findings were derived from the data using the “post-structuralist analytic strategy” outlined by Bonham and Bacchi (Citation2017), wherein the focus is on the discourses and practices underpinning “what is said and done” in texts and interviews, rather than the individuals saying/doing it and their experiences and motivations. This reflects the post-structuralist ontology and epistemology that inform our approach in this paper, and which hold that social realities are constituted and known through historically contingent sets of discursive and non-discursive practices.

Diversified Assistance, Housing Pathways and the Pursuit of Independence

To understand assistance allocations practices in our three jurisdictions we must first discuss the shifting governmentality of housing insecurity that is reshaping the provision of housing assistance. As in other countries (Blessing Citation2016), Australian housing authorities are decentring social housing provision in favour of a more diversified approach to addressing unmet housing need. Social housing is now one option amongst a suite of housing assistance “products” that also includes PRA and temporary accommodation for the homeless.

Part of the work that we’ve been doing has really been about presenting ourselves … as the place to come when you need assistance for housing, not the place to come when you want public housing. (Cheryl, Queensland Government)

There is a particular focus in this diversified approach to housing assistance on expanding PRA to offset the relative decline in social housing provision. For example, the NSW Government’s (2016, 5–6) Future Directions for Social Housing, 2016–2026 policy commits to providing “expanded support in the private rental market, reducing demand on social housing and the social housing wait list”. Consistent with this shift, in pure volume terms, provision of PRA now easily surpasses social housing tenancy allocations in each of the three states – and in Australia more broadly. Nationally 92,573 instances of PRA were newly provided in 2019–20, compared with only 31,917 new social housing lettings (Pawson and Lilley Citation2022, Table 4). Notably, the provision of these PRA products is in addition to the availability of Commonwealth Rent Assistance – a social security payment that acts as a demand-side housing subsidy for low income private renters and which – in terms of its national budget – has come to eclipse federal spending on social housing over recent decades (Pawson, Milligan, and Yates Citation2020).

The reference to reducing “demand” on the social housing system in the quote above suggests that a key aim of expanding PRA is to support the rationing of social housing (Pawson and Lilley Citation2022). Private rental assistance is far less resource-intensive than social housing, meaning that it enables governments to support a greater number of people at relatively low additional cost. If effective, such filtering also reserves social housing for households with the greatest need by supporting those with lesser need by other means. However, a closer look at the underpinning policy discourse reveals that rationing is not the only driver. Housing authorities are also animated by the normative neoliberal goal of encouraging as many households as possible to achieve “independence” by securing housing in the private market.

The expansion of PRA corresponds with the changing conceptualization of housing assistance in the three states. Rather than simply fulfilling unmet housing need through direct state provision, housing assistance is now animated by a “pathways”Footnote3 approach that aims to facilitate people’s movement along an imagined housing continuum, ranging from homelessness crisis accommodation and “sub-market” housing at one end to private rental and homeownership at the other (see for a diagrammatic example). The Queensland Government (Citation2017, 17) lists “Providing housing pathways” as a key aim of its Housing Strategy, 2017–2027, promising that “People will be connected to the services and support they need to move through the housing continuum including social and affordable housing, private rental and home ownership”. The NSW Government (2016, 5) states it “looks at the whole continuum of housing – from homelessness to the private market” to ensure that, amongst other things, there are “More opportunities, support and incentives to avoid and/or leave social housing” (NSW Government Citation2016, 5). And the Tasmanian Government (Citation2019, 15) claims its housing action plan “ … sets out the pathways for better access to a range of affordable housing options to avoid housing stress that can lead to homelessness”.

Figure 1. The housing continuum (adapted from Hughs Citation2020, p36).

Along with the desire to reduce pressure on the social housing system, these efforts to facilitate households’ transitions along a housing continuum are underpinned by the long-standing neoliberal goal of maximizing “independence” in the form of market engagement (Miller and Rose Citation2008). For instance, Queensland’s housing strategy repeatedly promises to provide low-income households with “pathways to independence” through enabling access to private rental housing or homeownership (e.g. 2017, 5). The implication here is that the further a household moves along the housing continuum (away from state provision and towards market offerings) the greater their independence. As Gemma, a Queensland Government interviewee, put it, “It’s all with the intention of getting the best outcomes for the household. And we do talk … in terms of assisting people to get to their level of independence”.

The flipside of the pursuit of independence is, of course, avoiding dependence on long-term state support. The NSW Government (2016, 5) is the most explicit on this point:

By 2025, Future Directions will seek to transform the social housing system in NSW from one … in which tenants have little incentive for greater independence and live in circumstances that concentrate disadvantage, to a dynamic and diverse system characterised by … housing assistance being seen as a pathway to independence and an enabler of improved social and economic participation for tenants living in vibrant and socioeconomically diverse communities. (NSW Government 2016, 5)

As this quote infers, social housing is problematized in the pathways approach as a driver of “welfare dependence”, with policy makers rehearsing the longstanding neoliberal fear that it “entrenches disadvantage” by creating disincentives to work and market consumption (NSW Government 2016, 7). As a result, efforts are made to discourage long-term social housing residency for all but the most vulnerable or “complex” tenants. A key aim of PRA is, therefore, to “divert” (NSW Government 2016, 25) most assistance applicants away from social housing and towards the relative “independence” of the private market. As a NSW Government interviewee explained to Aminpour and colleagues (Citation2023, 38), this is as much about “enabling” households to live a “better” life in the private rental sector as it is about alleviating pressure on the social housing system.

Interviewer: Can you just clarify for me … [is] the purpose of this [rental subsidy] scheme to alleviate pressure on the social housing waitlist?

Interviewee: I think that is one of the key considerations … But also, giving people who have the capacity, if they’re on the brink of, with some additional support that they could sustain a private rental without going into the social housing waiting list, there’s a case to be made that … they’re better off in private rental regardless of whether they should get social housing or not … There’s an enabling effect and also a diversionary factor.

Importantly, whilst maximizing independence is the declared aim of the pathways approach, policy makers recognize that households differ in their capacity to achieve this. Indeed, it is acknowledged that some households are unlikely to access and/or sustain a tenancy in the private market even with government assistance and therefore have a “legitimate dependence” on the state (Clarke et al. Citation2022, 17). As Mary, a Queensland non-profit interviewee who works closely with state government, put it:

We know there is a subset of people who probably need a subsidised housing solution for life. And even to sustain subsidised housing, they need … intensive … support.

This “subset” includes people with debilitating long-term vulnerabilities, such as “The frail aged and people living with a disability or a serious mental illness” (NSW Government, 2016, 7), as well as people with “complex needs” whose multiple and compounding vulnerabilities mean they cannot reasonably be expected to live “independently” in private rental housing.

There is therefore an imperative in the pathways approach to match housing assistance applicants to the forms of assistance that correspond to their “capacity for independence”. Whilst in some relatively rare cases this means allocating a long-term social housing tenancy, this is no longer the default outcome. Rather, the form of assistance provided is that most likely to enable a household to transition towards greater independence. As Gemma (Queensland Government interviewee) put it,

So, we know that everybody’s got different needs and we know that they might vary over time, but if people are capable of, with just a little bit of assistance, obtaining or maintaining some sort of private market solution … why wouldn’t we try and assist them to do that? And not necessarily have to have a certain square box of assistance that we might have provided previously [i.e. social housing].

Importantly, matching households to the most appropriate form of assistance require housing authorities to develop systems for assessing, classifying, and sorting households based on their individual needs and capacity. It is to these “social sorting” processes that we now turn.

Social Sorting in the Allocation of Housing Assistance

The adoption of the pathways approach has significant implications for how housing assistance is allocated in our three states. Whilst housing authorities continue to engage in traditional administrative rationing, such as testing eligibility and prioritizing the neediest or most deserving applicants, this is now incorporated within a broader set of social sorting practices informed by a more consumerist logic. Specifically, contemporary administrative practices are oriented to providing “tailored” responses to the diverse needs and capacities of different households. For instance, the Tasmanian Government (Citation2019, 15) states

Tasmania has the most integrated housing and homelessness system in Australia. Housing assistance ranges right across the entire housing spectrum, from homelessness services to home ownership assistance, and is aimed to match tailored solutions to a person’s individual needs.

There is a clear resonance between this commitment and the consumerist discourse of tailoring products and services to niche consumer markets (Clarke et al. Citation2007). Indeed, housing authorities explicitly adopt market nomenclature, referring to housing assistance offerings as “products” and applicants as “customers”. In the words of the then Queensland Housing Minister, her department strives “to tailor products and services to customer needs” (Enoch, quoted in Convery and Gillespie Citation2023). As with commercial firms, the desire to tailor housing assistance to “customer needs” requires housing authorities to develop ways of sorting assistance applicants for differential treatment (Lyon Citation2003). To this end, each of our three states has adopted new “integrated” and “person-centred” approaches to assessing assistance applications.

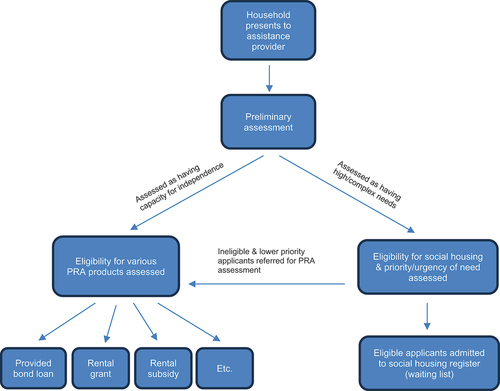

As housing assistance has diversified, housing authorities have adopted “holistic” approaches that integrate the assessment processes for different forms of assistance and treat applicants as a single population or “market” that can be sorted based on their individual circumstances (this is represented diagrammatically in below). In NSW and Tasmania, this has involved the development of new “one-stop-shop” systems dubbed “Housing Pathways” and “Housing Connect”, respectively. These systems aim to provide “an integrated housing assistance and support response” with “capacity to triage applicants into a range of housing options [and] deliver more appropriate and timely interventions” (Tasmanian Government Citation2013, 31). Queensland has introduced a practice it terms “pathway planning” that performs a similar integrative function. As Cheryl, a Queensland Government interviewee, explained, pathway planning aspires to establish a more “person-centred” approach:

Over the last couple of years we’ve shifted … our service response to be … person-centred and about doing holistic intake and assessment … So, trying to understand in a holistic sense [an applicant’s] needs as they present in a range of areas … We have a conversation we work through [called] … “pathway planning” … and we’ve implemented a customer management system … focused on the person, not … the products and services we’re delivering. So, we’ve had a range of different systems over time that are all about managing a bond loan, managing an application for social housing, and now we’ve got a customer management system that takes in that information from the [pathway planning] interactions that people are having.

Figure 2. The assessment & sorting of housing assistance applications (ideal type constructed by authors – actual procedures vary slightly by state).

The principle of “person-centredness” also informed Tasmania’s current approach to assessment and allocations.

It is a person-centred approach not just a system approach, and … it is following the line of there is no one-size-fits-all and things need to be tailored to the individual needs rather than just a formulaic way of doing it.

As Needham (Citation2011) explains, the discourse of public service “personalisation” has ambiguous political valances: it is deployed both in progressive efforts to empower service users and in neoliberal efforts reconfigure social services in accordance with consumerist principles. Whilst there are traces of both meanings in the above quotes, the neoliberal/consumerist interpretation clearly dominates: person-centredness is justified through the familiar neoliberal critique of “one-size-fits-all” bureaucratic provision as failing to respond to the diversity of household circumstances (Clarke et al. Citation2007).

Consistent with developments in other sectors (Ferreri and Sanyal Citation2022; Fey Henman Citation2022; Lyon Citation2003), these new consumerist allocations practices are supported by digital technologies and ADM tools. As found in existing studies (Eubanks Citation2018), these technologies support the rationing of scarce housing resources, particularly social housing tenancies, in our three states.

[We use] a very simple algorithm. It basically is: if you have this and this, then you equal “priority” … [I]f your household income is this amount, or if you’ve got a grade A health check, or if you’ve been assessed as having family violence, if your degree of homelessness is this and this and you’re exiting this type of property – all of these things are essentially algorithms in [the system] which spits out if you’re a priority or a general applicant.

However, ADM systems were also being used to help match applicants to the most appropriate assistance products. This was most explicit in NSW, where a government interviewee, Damian, described the following functionality.

So a client will apply for housing assistance and the way that our system works, our database works … our system will generate products that that client may be eligible for and may be assessed for … Frontline staff can [then] assess them for any of those products.

Thus, as seen in other sectors, digital technologies have come to play an important role in enabling the increasingly fine-grained sorting functions required to allocate assistance in a diversified approach to addressing housing insecurity.

The language of “tailoring” and “person-centredness” implies that it is applicants’ needs and circumstances that drive allocations decisions. Yet, in the context of the pathways approach, needs and circumstances are assessed primarily to determine their impact on an applicant’s capacity for market independence. Reflecting on what person-centred assessment means for social housing allocations, a Queensland Government interviewee stated, “we have started to look at, from a cohort perspective, who is going to be in that group less able to move towards independence somewhere else” (Cheryl). By contrast, an allocation of PRA depends on whether assessment of an applicant’s circumstances suggests the “opportunity” for social mobility (Blessing Citation2016). For instance, in allocating its three-year rental subsidy, Rent Choice, the NSW Government prioritizes “Young people transitioning to independent living” and “Adults with persistent low income who are prepared to commit to improving employment outcomes” (NSW Government 2016, 16). A NSW non-government interviewee, Bobby, reflected that the subsidy is allocated to applicants assessed as “not likely to chronically need support”.

In both examples, the neoliberal goal of maximizing market independence informs how and why applicants’ needs are assessed. Indeed, it provides the underlying rationality for the consumerist allocation logics outlined in this section. Practices like person-centred assessments and ADM solutions sort people for different forms of housing assistance, not based on their objectively- or self-defined needs, but rather on judgements of their position on the pathway to housing independence.

Discussion and Conclusion

This paper has examined how changes in the governmentality of housing insecurity, embodied particularly in the diversification of housing assistance, is reshaping how Australian housing authorities assess, and allocate resources to, households seeking support. Drawing on findings from research in three Australian states, we have demonstrated that allocations practices today do more than merely ration scarce resources; they also sort people for different kinds of assistance responses over and against the neoliberal goal of maximizing market independence.

To be sure, each individual form of assistance continues to be rationed through the kinds of administrative practices documented in previous studies. Social housing is rationed by prioritizing those applicants with the greatest/most complex needs (Clarke et al. Citation2022; Rita, Garboden, and Darrah-Okike Citation2022), whereas market-based assistance (like PRA) is rationed by restricting eligibility to lower-risk applicants more likely to capitalize on the “opportunities” that housing assistance provides (Blessing Citation2016; Humphry Citation2020; Zhang and Johnson Citation2023). However, when taken together and situated in the context of the “integrated” and “person-centred” allocations systems documented above, these administrative practices clearly do more than ration scarce resources. They also classify and sort people facing housing insecurity in ways that have significant implications for their prospect of achieving stable housing.

Given the diversification of housing assistance is occurring across a range of Anglophone and other countries (Blessing Citation2016; Colburn Citation2021), along with the increasing emphasis on promoting “economic opportunity” and independence (Blessing Citation2016), it is likely that some variation of the social sorting practices document here are developing – or will develop – in these other jurisdictions as well. However, the extent to which our findings are transferable to other Anglophone countries (or indeed beyond) is a question for future research.

A key implication of our findings is that, behind the neutral consumerist rhetoric of tailored “products” and person-centred assessment of needs, Australian housing authorities are engaged in a profoundly normative – indeed, paternalistic – project of maximizing market engagement. As we showed, the social sorting functions performed by assistance allocations are underpinned by a belief that most households seeking assistance are better off in the private rental sector because it signifies “independence” and enables social mobility. The key task for housing authorities thus becomes assessing whether a household has the capacity to access/sustain market housing if provided appropriate state support, typically a bond loan or rental grant, but also increasingly rental subsidies. The flip side is the belief that social housing – which was central to how countries like Australia addressed housing insecurity for the second half of the 20th century – is detrimental to all but the most vulnerable because of its association with dependence. Again, the key task becomes sorting out for whom social housing is an unavoidable outcome, given their extremely limited capacity to sustain a private tenancy, and who can be “diverted” to the private market.

The paternalistic quality of this approach, and the social sorting practices that enact it, is particularly stark when contrasted with research on the self-defined needs and preferences of people seeking housing assistance. Flanagan and colleagues’ (Citation2020) research showed assistance applicants in Australia preferred social housing for the relative security it provided. Indeed, participants described the profound insecurity they experienced in the private rental sector as undermining their self-defined need for physical and ontological security. Thus, despite claims to tailoring assistance to “customer” needs, the approach taken by Australian housing authorities contradicts the self-defined needs of many of those very “customers”. This perhaps reflects the faith governments place in the epistemological prowess of digital social sorting systems, whose capacity for fine-grained, data-driven classifications gives them the veneer of objectivity and thus an ability to know people’s “true” needs better than they can themselves (Eubanks Citation2018; Fey Henman Citation2022).

Importantly, existing research evidence belies the assumption (explicit or otherwise) that low-income households are better off in the private rental sector, and that the insecurity of private renting is ameliorable through PRA. O’Donnell (Citation2021, 1722) shows that, in Australia, “social housing is associated with greater stability in housing trajectories for disadvantaged populations” compared to private rental housing, whereas PRA had limited impact on housing stability. Blunden and Flanagan’s (Citation2022, 1909) research on responses to the housing needs of Australian women escaping domestic violence found that PRA often fails to enable women to access stable and affordable housing, leading to “a forced return to the perpetrator” being an “unacceptably common” outcome . Beyond Australia, international research shows that the effectiveness of PRA in assisting people to achieve stable housing is contingent on market conditions and, given that rental markets are typically poorly regulated in the liberal market economies of the Anglophone world, these conditions are often unfavourable (Colburn Citation2021). Indeed, the number of homes affordable to low-income earners provided by the market in Australia has been steadily declining for decades. In the 20 years to 2016, the national shortfall in the number of tenancies affordable to lowest income quintile renters increased from 48,000 to 212,000 (Hulse et al. Citation2019). Australian private renters are also afforded few protections in tenancy law relative to international standards (Morris, Hulse, and Pawson Citation2021), meaning that, even where affordability issues are attenuated through PRA, tenants can continue face significant housing insecurity (e.g. short, fixed-term leases, eviction without grounds, etc.).

Given this, the social sorting practices described in this paper essentially function to divert large numbers of assistance applicants back to the insecure housing circumstances that created their need for assistance in the first place, albeit with a modicum of support to help them manage this insecurity. Thus, the outcome experienced by these households is likely to be an entrenchment of their housing insecurity and limiting of their social mobility, rather than progression along the housing continuum towards greater independence as assumed in the “pathways” discourse that animates Australia’s social sorting system.

Social sorting also serves to deepen the residualisation of social housing (Angel Citation2023) by further filtering out all but the most “complex” or acutely needy households and reinscribing the view that social housing is a “welfare safety net” or “ambulance service” (Fitzpatrick and Pawson Citation2007, Citation2014) that can/should only play a marginal role in the housing system. It thus runs contrary to campaigns from scholars and housing advocates for the establishment of a more universalist approach that treats access to affordable, safe, and secure housing as a right (Marcuse and Madden Citation2016; Mazzucato and Farha Citation2023). Indeed, the logic of social sorting, with its preoccupation with providing tailored responses to individual circumstances, obscures such common needs in favour of a focus on particularistic ones related to households’ individual “pathways” and position along the housing continuum.

Whilst some might argue that this targeting and residualism is necessary to ration scarce public resource in the context of government budgetary constraints, it is noteworthy that Australia’s generous support for homeowners and property investors is not subject to these strictures. All property owners are afforded either a discount on (investors), or exemption from (owner occupiers), their capital gains tax liabilities regardless of their circumstances, and all investors are eligible to deduct losses made from their rental properties from their taxable income through Australia’s “negative gearing” arrangements, despite these policies costing government billions of dollars a year in foregone revenue (Daley and Wood Citation2016). This suggests that greater universalism is indeed possible when there is political support for it. But of course, these forms of private ownership are viewed as the epitome of housing independence: the imagined destination of the normative housing pathway. In our view, this further reinforces the need to look beyond rationing logics and their material justifications (resource scarcity) to reveal – and challenge – the normative assumptions that drive ineffective neoliberal responses to housing insecurity.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Herein we use the term “social housing” to refer to both public housing owned and managed directly by the state and social housing managed (and sometimes owned) by non-profit organizations, provided at rents well below market rates and targeted to low-income and otherwise disadvantaged populations.

2. Since it involved a much shallower subsidy than that traditionally provided for social housing, the “affordable rent” product, introduced under the 2010–2015 UK Government and deployed in England also involved rents typically set at 80% of market rates.

3. N.B. the concept of “housing pathways” deployed in Australian housing policy is somewhat different to how it is understood in housing research (see Flanagan et al. Citation2020).

References

- Alden, S. 2015. “On the Frontline: The Gatekeeper in Statutory Homelessness Services.” Housing Studies 30 (6): 924–941. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2014.991380.

- Aminpour, F., I. Levin, A. Clarke, C. Hartley, E. Barne, and H. Pawson. 2023. “Getting off the waiting list? Managing housing assistance provision in an era of intensifying social housing shortage.” InAHURI Final Report No. 422,Australian, Melbourne: Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited.

- Angel, S. 2023. “Housing Regimes and Residualization of the Subsidized Rental Sector in Europe 2005-2016.” Housing Studies 38 (5): 881–901. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2021.1921122.

- Blessing, A. 2016. “Repackaging the Poor? Conceptualising Neoliberal Reforms of Social Rental Housing.” Housing Studies 31 (2): 149–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2015.1070799.

- Blunden, H., and K. Flanagan. 2022. “Housing Options for Women Leaving Domestic Violence: The Limitations of Rental Subsidy Models.” Housing Studies 37 (10): 1896–1915. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2020.1867711.

- Bonham, J., and C. Bacchi. 2017. “Cycling ‘Subjects’ in Ongoing-Formation: The Politics of Interviews and Interview Analysis.” Journal of Sociology 53 (3): 687–703. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783317715805.

- Burke, T. and K. Hulse. 2003. “Allocating Social Housing.” Paper presented at National Housing Conference, Adelaide, November 26-28.

- Clapham, D., and K. Kintrea. 1986. “Rationing, Choice and Constraint: The Allocation of Public Housing in Glasgow.” Journal of Social Policy 15 (1): 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279400023102.

- Clapham, D., and K. Kintrea. 1991. “Housing Allocation and the Role of the Public Rented Sector.” InThe Housing Service of the Future, edited by D. Donnison and D. Maclennan 53–74. Harlow: Longman.

- Clarke, A., L. Cheshire, and C. Parsell. 2020. “Bureaucratic Encounters “After neoliberalism”: Examining the Supportive Turn in Social Housing Governance.” The British Journal of Sociology 71 (2): 253–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12740.

- Clarke, A., L. Cheshire, C. Parsell, and A. Morris. 2022. “Reified Scarcity & the Problem Space of ‘Need’: Unpacking Australian Social Housing Policy.” Housing Studies 39 (2): 565–583. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2022.2057933.

- Clarke, J., J. Newman, N. Smith, E. Vidler, and L. Westmarland. 2007. Creating Citizen-Consumers: Changing Publics and Changing Public Services. London: Sage.

- Colburn, G. 2021. “The Use of Markets in Housing Policy: A Comparative Analysis of Housing Subsidy Programs.” Housing Studies 36 (1): 46–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2019.1686129.

- Convery, S., and E. Gillespie. 2023. “‘It’s Just Been a hellride’: How the End of the Affordable Housing Scheme Is Pushing Families to the Edge.” The Guardian Australia. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2023/apr/10/its-just-been-a-hellride-how-the-end-of-the-affordable-housing-scheme-is-pushing-families-to-the-edge.

- Cowan, D., and M. McDermont. 2006. Regulating Social Housing: Governing Decline. Milton Park: Taylor & Francis.

- Daley, J., and D. Wood. 2016. Hot Property: Negative Gearing and Capital Gains Tax Reform. Melbourne: Grattan Institute.

- DeLuca, S., and E. Rosen. 2022. “Housing Insecurity Among the Poor Today.” Annual Review of Sociology 48 (1): 343–371. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-090921-040646.

- Esping-Andersen, G. 1990. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Eubanks, V. 2018. Automating Inequality: How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police, and Punish the Poor. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- Ferreri, M., and R. Sanyal. 2022. “Digital Informalisation: Rental Housing, Platforms, and the Management of Risk.” Housing Studies 37 (6): 1035–1053. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2021.2009779.

- Fey Henman, P. 2022. “Digital Social Policy: Past, Present, Future.” Journal of Social Policy 51 (3): 535–550. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279422000162.

- Fields, D., and D. Rogers. 2021. “Towards a Critical Housing Studies Research Agenda on Platform Real Estate.” Housing Theory & Society 38 (1): 72–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2019.1670724.

- Fitzpatrick, S., and H. Pawson. 2007. “Welfare Safety Net or Tenure of Choice? The Dilemma Facing Social Housing Policy in England.” Housing Studies 22 (2): 163–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673030601132763.

- Fitzpatrick, S., and H. Pawson. 2014. “Ending Security of Tenure for Social Renters: Transitioning to ‘Ambulance service’social Housing?” Housing Studies 29 (5): 597–615. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2013.803043.

- Fitzpatrick, S., H. Pawson, G. Bramley, J. Wood, B. Watts, M. Stephens, and J. Blenkinsopp. 2019. Homelessness Monitor England 2019. London: CRISIS.

- Fitzpatrick, S., and M. Stephens. 1999. “Homelessness, Need and Desert in the Allocation of Council Housing.” Housing Studies 14 (4): 413–431. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673039982704.

- Flanagan, K., I. Levin, S. Tually, M. Varadharajan, J. Verdouw, D. Faulkner, A. Meltzer, and A. Vreugdenhil. 2020. Understanding the Experience of Social Housing pathways, AHURI Final Report No. 324. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute.

- Foucault, M. 2007. Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1977–1978. M. Senellart & A. I. Davidson, edited by. New York: Picador.

- Foucault, M. 2008. The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1978-79. M. Senellart & A. I. Davidson, edited by. New York: Picador.

- Goetz, E. G. 2011. “Where Have All the Towers Gone? The Dismantling of Public Housing in US Cities.” Journal of Urban Affairs 33 (3): 267–287. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9906.2011.00550.x.

- Hughes, E. 2020. “Addressing Homelessness Though Unblocking the Housing Continuum.” Parity 35 (8): 36–38.

- Hulse, K., and T. Burke. 2005. The Changing Role of Allocations Systems in Social Housing. A. H. a. U. R. Institute.

- Hulse, K., M. Reynolds, C. Nygaard, S. Parkinson, and J. Yates. 2019. The Supply of Affordable Private Rental Housing in Australian Cities: Short-Term and Longer-Term Changes. AHURI Final Report No. 323. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited.

- Humphry, D. 2020. “From Residualisation to Individualization? Social tenants’ Experiences in Post-Olympics East Village.” Housing Theory & Society 37 (4): 458–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2019.1633400.

- Jacobs, K. 2019. Neoliberal Housing Policy: An International Perspective. London: Routledge.

- Keene, D. E., A. Rosenberg, P. Schlesinger, S. Whittaker, L. Niccolai, and K. M. Blankenship. 2023. ““The Squeaky Wheel Gets the Grease”: Rental Assistance Applicants’ Quests for a Rationed and Scarce Resource.” Social Problems 70 (1): 203–218. https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spab035.

- Kim, H. 2022. “Failing the Least Advantaged: An Unintended Consequence of Local Implementation of the Housing Choice Voucher Program.” Housing Policy Debate 32 (2): 369–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2020.1834429.

- Lidstone, P. 1994. “Rationing Housing to the Homeless Applicant.” Housing Studies 9 (4): 459–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673039408720800.

- Lipsky, M. 1980. Street-Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services. Russell Sage Foundation. https://doi.org/10.7758/9781610447713.

- Lyon, D. 2003. Surveillance As Social Sorting: Privacy, Risk, and Digital Discrimination. London: Routledge.

- Marcuse, P., and D. Madden. 2016. In Defense of Housing: The Politics of Crisis. London: Verso Books.

- Mazzucato, M., and L. Farha. 2023. “The Right to Housing: A Mission-Oriented and Human Rights-Based Approach.” In Council on Urban Initiatives (CUI WP 2023-01), London: UN HABITAT, LSE Cities & UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose.

- Miller, P., and N. Rose. 2008. Governing the Present: Administering Economic, Social and Personal Life. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Moore, K. 2016. “Lists and Lotteries: Rationing in the Housing Choice Voucher Program.” Housing Policy Debate 26 (3): 474–487. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2015.1129984.

- Morris, A., A. Clarke, C. Robinson, J. Idle, and C. Parsell. 2023. “Applying for Social Housing in Australia–The Centrality of Cultural, Social and Emotional Capital.” Housing Theory & Society 40 (1): 42–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2022.2085169.

- Morris, A., K. Hulse, and H. Pawson. 2021. The Private Rental Sector in Australia: Living with Uncertainty. Singapore: Springer.

- Morris, A., C. Robinson, J. Idle, and D. Lilley. 2022. “Ideal Bureaucracy? The Application and Assessment Process for Social Housing in Three Australian States.” International Journal of Housing Policy 24 (2): 224–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2022.2132460.

- Needham, C. 2011. Personalising Public Services: Understanding the Personalisation Narrative. Bristol: Policy Press.

- New South Wales Government. 2016. Future Directions for Social Housing in NSW. Sydney: NSW Government.

- O’Donnell, J. 2021. “Does Social Housing Reduce Homelessness? A Multistate Analysis of Housing and Homelessness Pathways.” Housing Studies 36 (10): 1702–1728. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2018.1549318.

- Pawson, H., C. Brown, and A. Jones. 2009. Exploring Local Authority Policy and Practice on Allocations. London: Communities and Local Government Dept.

- Pawson, H., and K. Hulse. 2011. “Policy Transfer of Choice-Based Lettings to Britain and Australia: How Extensive? How Faithful? How appropriate?.” International Journal of Housing Policy 11 (2): 113–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616718.2011.573199.

- Pawson, H., and D. Lilley. 2022. Managing Access to Social Housing in Australia: Unpacking Policy Frameworks and Service Provision Outcomes. Kensington: City Futures Research Centre (UNSW).

- Pawson, H., V. Milligan, and J. Yates. 2020. Housing Policy in Australia. Springer Singapore Pte. Limited. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-0780-9.

- Pawson, H., and D. Watkins. 2007. “Quasi-Marketising Access to Social Housing in Britain: Assessing the Distributional Impacts.” Journal of Housing & the Built Environment 22 (2): 149–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-007-9080-y.

- Peck, J., and A. Tickell. 2002. “Neoliberalizing Space.” Antipode 34 (3): 380–404. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8330.00247.

- Preece, J. and E. Bimpson. 2019. Forms and Mechanisms of Exclusion in Contemporary Housing Systems: An Evidence Review. Glasgow: UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence.

- Queensland Government. 2017. Queensland Housing Strategy, 2017-2027. Brisbane: Queensland Department of Housing and Public Works.

- Richter, P., and J. Cornford. 2008. “Customer Relationship Management and Citizenship: Technologies and Identities in Public Services.” Social Policy & Society 7 (2): 211–220. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746407004162.

- Rita, N., P. M. Garboden, and J. Darrah-Okike. 2022. ““You Have to Prove That You’re Homeless”: Vulnerability and Gatekeeping in Public Housing Prioritization Policies.” City & Community 22 (2): 83–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/15356841221129791.

- Scanlon, K., M. Arrigoitia Fernández, and C. Whitehead. 2015. “Social Housing in Europe.” European Policy Analysis 17: 1–12.

- Tasmanian Government. 2019. Tasmania’s Affordable Housing Action Plan, 2019-2023. Hobart: Tasmanian Government.

- Van Dijck, J. 2014. “Datafication, Dataism and Dataveillance: Big Data Between Scientific Paradigm and Ideology.” Surveillance & Society 12 (2): 197–208. https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v12i2.4776.

- Wacquant, L. 2012. “Three Steps to a Historical Anthropology of Actually Existing Neoliberalism.” Social Anthropology 20 (1): 66–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8676.2011.00189.x.

- Zhang, S., and R. A. Johnson. 2023. “Hierarchies in the Decentralized Welfare State: Prioritization in the Housing Choice Voucher Program.” American Sociological Review 88 (1): 114–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/00031224221147899.