Abstract

This study makes an empirical contribution by exploring factors that contribute to the competitiveness of Latvian companies. The paper draws on a survey of owner-managers to determine the availability and use of resources and strategies found to be important drivers for firms’ competitiveness. Overall, we identify a number of firm-level factors, including involvement in risk-taking behaviour, more extensive use of networking channels, and efficient use of various business strategies as potential sources to increase the competitiveness of Latvian companies. Company owner-managers, however, tend to be more productive in using available human resources, and are satisfied with the availability of physical resources in addition to having a strong export orientation. The study also indicates various shortcomings in the external environment which, as perceived by respondents, are a burden for competitive entrepreneurship activities in the Latvian market. In this light, albeit of an exploratory nature, this study can be used as a source for evidence-based entrepreneurship policies in Latvia and other countries of Central and Eastern Europe.

1. Introduction

Competitiveness is a topic of major importance not only for public and industrial policy-makers, but also from the firm's perspective. In spite of its importance being a multidimensional phenomenon, competitiveness lacks a unified definition, as macro-, meso-, and microeconomic approaches all define competitiveness differently (Buzzigoli & Viviani, Citation2009; Nelson, Citation1992; Porter & Ketels, Citation2003). Furthermore, competitiveness as a concept can involve various disciplines – comparative advantage, a strategy and management perspective, a historical and sociocultural perspective, amongst others (Waheeduzzaman & Ryans, Citation1996) and, depending on the approach, can be treated as both dependent or independent and an intermediary variable. Regardless of the approach and disciplines covered, however, competitiveness is usually associated with four key characteristics (Man, Lau, & Chan, Citation2002): long-term orientation, controllability, relativity, and dynamism.

In this light, much attention in economics literature has so far been paid to assessing competitiveness on the country level, which has involved measuring performance of institutions, per capita income levels, levels of productivity, and comparative costs amongst others worldwide (Kitson, Martin, & Tyler, Citation2004; Porter, Citation1992), and in the Latvian context (Benkovskis, Citation2002). Analysis of competitiveness on the firm level, especially identifying and discussing various potential drivers of competitiveness of small and medium-sized businesses (SMEs), is, however, a relatively disregarded area (e.g. Man et al., Citation2002). This is somewhat surprising as competitive companies, including SMEs, are some of the cornerstones of economic growth for any country.

According to entrepreneurship theories (e.g. McKelvie & Davidsson, Citation2009), competitive companies, amongst other things, should be innovative, oriented towards providing services and products that have high added value and that are export capable. In addition, competitive companies are able to adapt to the influence of different environmental and time factors while successfully developing their business. However, existing empirical studies do not provide any specific answer as to why one company is more competitive than the other (e.g. Man et al., Citation2002). This, in turn, seems to be quite natural, since the competitiveness of a company is influenced not only by specific factors, but also by combinations of such factors, which are further dependent on many other factors, for example, external environment, also luck. Similar to business processes in general, combinations of factors that drive competitiveness are sometimes not only complicated, but also not always logically explainable. This is the reason why it is difficult not only to define firm-level competitiveness, but also to measure it, that is, what has brought success to one company will not necessarily be as useful to other companies precisely due to various additional determining factors.

Nevertheless, previous entrepreneurship studies (e.g. Buzzigoli & Viviani, Citation2009; Hoang & Antoncic, Citation2003; Malecki & Veldhoen, Citation1993; Man et al., Citation2002; McKelvie & Davidsson, Citation2009; Roper, Citation1998) have identified a range of factors that may potentially foster competitive business when applied separately and/or in different combinations. These factors are summarized in . It should be pointed out, however, that the aim of the figure, similar to the article in general, is not to analyse extensively how various combinations of these factors contribute to the competitiveness of the companies, as this would require a qualitative approach, such as case studies, the results of which would be harder to generalize. Instead, the paper aims to provide an insight into to what extent Latvian entrepreneurs exploit various tools that, according to entrepreneurship literature, are seen as determinants of competitive business. It has to be added that the significance of the various factors in might differ also depending on, for example, the size or the economic sector of the company.

Figure 1. Determinants of business competitiveness.Source: The author, based on a review of entrepreneurship literature.

It is, of course, impossible to include an assessment of all the factors mentioned in in one study. Thus, we have chosen to analyse what, according to entrepreneurship literature (e.g. Man et al., Citation2002; McKelvie & Davidsson, Citation2009), seem to be the most significant factors determining competitiveness of the companies: access to resources (including human resources, physical, and financial resources) and efficiency of their use, business strategies, internal and external communication networks, influence of the external environment, as well as indicators of a company's financial performance as compared to their competitors.

The next section describes the methodology of the study paying particular attention to the theoretical considerations at the heart of the questionnaire. The third section proceeds with presenting an analysis of the main results, but the key conclusions and recommendations are provided in the final section.

2. Method and theoretical framework

This paper draws on a survey carried out in May and June 2011 involving 410 randomly selected Latvian company owner-managers. The survey was done via telephone interviews obtaining the information about companies from the Orbis database maintained by Bureau Van Dijk. In the study we used a questionnaire formFootnote1 that consists of six main sections that are further described in the following sections. Descriptive statistics and correlations amongst key variables are further provided in .

2.1. Measuring the availability and efficiency of human and physical resources

In the first section, there are several questions that focus on the quality of human resources as well as how efficient each company is in employing human capital. Quality of human resources and their efficient use are indeed amongst the key factors that companies should possess to ensure competitiveness. Namely, several studies (e.g. Man et al., Citation2002; McKelvie & Davidsson, Citation2009) indicate that competitiveness of a company is directly linked to the efficiency, motivation, and loyalty of their employees. Besides, generation of new ideas, often coming from the employees, is a factor that increases competitiveness of the company, often through innovations (Subramaniam & Youndt, Citation2005).

Good customer service skills and ability to sell products or services are directly linked to the financial performance of the company (Hitt, Bierman, Shimizu, & Kochhar, Citation2001; Rauch, Frese, & Utsch, Citation2005). Furthermore, to ensure competitive business especially in firms where it is necessary to invest considerable time and financial resources in staff training, it is important to provide for optimum job rotation (McKelvie & Davidsson, Citation2009). In the questionnaire, we asked the company owner-managers to evaluate their employees in regards to each of the aforementioned aspects. The answers were measured using a scale from ‘1' to ‘7', where ‘1' stands for a very weak situation, but ‘7' corresponds to a competitive business in human resources accessibility and their efficient use. The first section of the questionnaire also includes a question on staff training, and we also asked the company owner-managers to evaluate their access to such other important resources, as, for example, information technologies and any technical equipment crucial to ensure competitive business.

To ensure competitive business, the role of people managing a firm, namely, owners and managers, is crucial (e.g. Alvarez & Busenitz, Citation2001). Thus, in order to better assess competitiveness of the companies from this human resources aspect, we included a number of questions in the questionnaire to evaluate the ‘quality’ of the owner-managers, mainly their education level and former business experience. Previous studies have proved that a higher education level (e.g. Bantel & Jackson, Citation1989; Hambrick & Mason, Citation1984) and greater business experience of the owner-managers (King & Tucci, Citation2002) have a significant positive influence on the companies’ performance indicators and their overall competitiveness (e.g. Davidsson, Citation2006; Gimeno, Folta, Cooper, & Woo, Citation1997).

2.2. Measuring the quality of business strategies

The second section of the questionnaire is dedicated to the business strategies. More specifically, drawing on Porter's theory of competitive business (Citation1990), we offered the company owner-managers the opportunity to evaluate their company strategies against cost leadership, differentiation (i.e. offering products or services with high added value), and focussing on specific target markets. The answers of respondents were measured by an evaluation scale from ‘1' to ‘7', where, in accordance with business theories, the companies having an evaluation of their current business strategies closer to ‘7' should be more competitive as compared to those whose evaluation is closer to ‘1' (see e.g. Gilley & Rasheed, Citation2000; Hamermesh, Marshall, & Pirmohamed, Citation2002; Knight & Cavusgil, Citation2005; Mudambi & Zahra, Citation2007).

The following section of the questionnaire continues by analysing company strategies from the entrepreneurial orientation's (EO's) point of view. EO is a widely used research tool in entrepreneurship literature, and it is applied to assess three business strategy elements that are significant for a competitive business: innovation, risk-taking, and proactivity (regarding work with competitors) (Covin & Slevin, Citation1989; Miller, Citation1983). Previous studies (Baker & Sinkula, Citation2009; Hughes & Morgan Citation2007; Kreiser, Marino, & Weaver, Citation2002; Moreno & Casillas, Citation2008; Rauch, Wiklund, Lumpkin, & Frese, Citation2009; Short, Broberg, Cogliser, & Brigham, Citation2009) have proved that the companies in which the business orientation towards innovation, risk-taking, and proactivity is higher are better performers and thus more competitive in comparison to companies with lower EO.

When analysing the competitiveness of a company, apart from taking into account the current achievements, also the ability of the company managers to assess and prevent any potentially weak sides in the further business operations should be considered (Man et al., Citation2002). Based on this, we included a question asking the respondents to evaluate their company priorities in introducing various processes that, according to the entrepreneurship literature, are important to ensure competitive business. We also included a question about the size of export analysing to what extent companies concentrate on local or foreign markets, which is another crucial aspect of a competitive business (e.g. Ibeh, Citation2003; Roper, Citation1998).

2.3. Measuring the communication networking aspect

In order to implement a successful business strategy and, thus, increase competitiveness, it is not only the resources that are owned by the company are important. It is also the ability of the firm to attract various external resources. These resources are often available free of charge or for relatively little financial or time investment. To give some examples of resources promoting competitiveness, we can mention information that companies can get from their suppliers, clients, and also competitors; cooperation with organizations promoting entrepreneurship, for example, to generate new contacts or markets for one's products; cooperation with universities and research institutes to develop new, innovative products and services, etc. (see Greve & Salaff, Citation2003; Hoang & Antoncic, Citation2003; Robson & Benett, Citation2000). In order to find out to what extent the Latvian companies benefit from different communication channels that potentially give access to various resources promoting competitiveness, we included a third section on communication networks in the questionnaire.

2.4. Measuring access to financial resources

When emphasizing the significance of human and physical resources, we cannot neglect another, probably one of the most important aspects in ensuring any company's operation and competitiveness, namely, access to financial resources and their efficient use (see, e.g. Becchetti & Trovatto, Citation2002; Bougheas, Citation2004; Pissarides, Citation1999). This aspect of competitiveness is analysed in detail in the fourth section of the questionnaire.

2.5. Assessing the influence of external environment and comparison with competitors

Further on, in the fifth section, we turn our attention to external environmental factors affecting business competitiveness, namely, to what extent the company owner-managers think that the markets they work in are favourable for doing business (see Dess & Beard, Citation1984; Miller & Friesen, Citation1982). In the sixth section, however, the company managers are asked to evaluate their business growth both from the financial and the social aspects, thus demonstrating to what extent the specific company has managed to create value with the available resources for itself and the surrounding environment, as well as how successful it has been in comparison with its competitors (see, e.g. Sauka, Citation2008).

The results of the study on competitiveness of the Latvian companies are presented in the next section. Based on these results, we will look at how competitive the Latvian companies are from the point of view of specific factors covered by the questionnaire, that is, we will analyse competitiveness of the Latvian companies from the angle of human resources quality, accessibility of physical and financial resources, and the efficiency of their use, as well as the use of competitive business strategies. We will also consider to what extent companies make use of different communication networks and how they assess the influence of the external environment. Furthermore, their performance indicators as compared to the main competitors will be addressed.

3. Results

3.1. Human resources and their efficiency

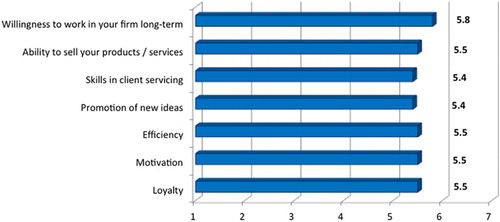

Most of the entrepreneurs, irrespective of company size or the economic sector they represent, would agree that workforce is at the heart of business success and competitiveness. The study results let us conclude that in general owner-managers of the Latvian companies are rather satisfied with their employees. Important aspects of a competitive business, such as employees’ willingness to work in the company long term, ability to sell products and services, and to service clients, promotion of new ideas, employees’ efficiency, motivation to work, and loyalty have been evaluated within 5.5–5.8 in a scale from ‘1' to ‘7' (where ‘7' means highly competitive workforce quality –- see ). Furthermore, one of the most effective ways to improve and maintain sufficiently high workforce quality is investment in staff training. The results of the study show that the Latvian companies are quite active in this regard, namely, slightly more than a half (53%) of the surveyed companies have trained their employees during the last year with the aim to improve their skills in product manufacturing or service provision.

Previous entrepreneurship studies also indicate that in addition to workforce efficiency, the education level of the company owner-managers plays a crucial role in ensuring business competitiveness (Alvarez & Busenitz, Citation2001; King & Tucci, Citation2002). The importance of these two factors stands out in micro and small enterprises where the company owner-managers are often the only human resource at the disposal of the company. Although the role of the owner-managers might be different, the education and skills of the company managers are certainly very important in big corporations as well. In this light, similar to other studies carried out in Latvia (see Baltrušaitytė-Axelson, Sauka, & Welter, Citation2008; Sauka, Citation2008), the results of this study also point towards a high or even very high level of education among the company managers. Almost 50% of the surveyed company owner-managers hold a bachelor's degree, and 22% a Master's degree. At this point it has to be added, however, that the quality of the acquired education also should be taken into consideration when interpreting the earned degrees, which, however, cannot be done precisely enough in this study.

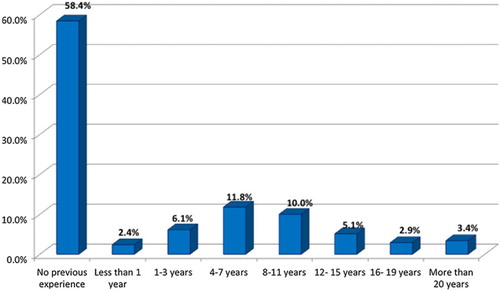

In regards to the experience of the Latvian owner-managers, the study shows that almost 40% of the surveyed respondents have been involved in entrepreneurship or business management prior to starting the specific company –- see . This type of experience – both positive and negative, especially experience in which the entrepreneurs have studied the market, learnt the ‘rules of the game', and maybe even got financial capital and contacts – usually serves as a foundation for a successful business in the future. We can conclude that ‘preparedness' of the Latvian entrepreneurs is at least sufficient to hope for competitive activity of the current businesses.

3.2. Access to physical resources

In addition to questions about the quality of the available workforce, the Latvian company owner-managers were asked to what extent they have access to physical resources, for example, information technologies and different facilities to manufacture products or provide services. The results show that, in general, the Latvian entrepreneurs see access to physical resources that are significant to ensure a competitive business, as comparatively good. On a scale from ‘1' to ‘7', where ‘7' means sufficient access to physical resources, the average evaluation is 5.7.

3.3. Strategies

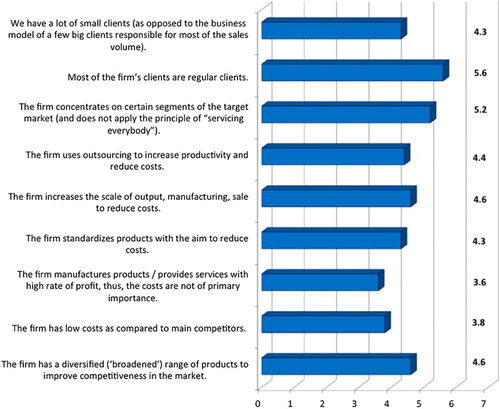

The basis of a competitive business is not only access to relevant resources, but also the way these resources are used, that is, business strategies. The main findings with regards to the strategies exploited by Latvian companies are summarized in .

3.3.1. Work with customers

A successful business strategy is first of all linked to care for the client who is the main source of business income. There is a well-grounded opinion that especially for companies without a sufficiently stable resource base and for optimum risk-sharing, it is too risky to concentrate only a few main clients long term. In these cases the focus on few and big clients most often means sizable orders. At the same time, especially, small and medium enterprises have to be aware of their huge dependency on the often specific wishes of these clients, as well as changes of these wishes (e.g. changing market conditions, results of technology development, etc.), which can rather frequently end up in bankruptcy.

Although business theories do not provide any specific answer as regards the ‘optimal' number of clients to be serviced, at the heart of particularly long-term business growth one would most often find business strategies oriented towards comparatively many, though small, customers. Experience of numerous firms has confirmed that such a strategy ensures more stable and predictable income and, in the case of small and medium enterprises in particular, it can ensure accumulation of a sufficient resource base – so that in the long run they could afford the risk of servicing big or even very big clients (Sauka, Citation2013; Simon, Citation2009; Zahra & Covin, Citation1993).

The results of this study, as shown in , show that the Latvian entrepreneurs are somewhere in the middle as regards the choice of the concerned strategy element (4.3 out of 7), which is relatively positive. Another positive aspect, according to the data, is that the Latvian companies take good care of their existing clients, namely, the questionnaire demonstrated that most of the clients of the Latvian companies are regular clients (the evaluation is 5.6 out of 7) – a doubtlessly very important aspect in ensuring competitiveness.

3.3.2. Diversification of products range

Entrepreneurial theories also indicate that one of the elements promoting competitiveness, especially in the long run, is the ability to diversify the range of the offered products or services (see Simon, Citation2009; Wright, Perris, Hiller, & Kroll, Citation1995). There are several success stories, including Latvian companies working in international markets (see Sauka, Citation2013; Sauka & Welter, Citation2012), that prove this statement – with the help of a diversified product range companies can no longer be affected by plummeting sales of a particular product, which is, of course, crucial to strengthen competitiveness. According to the findings of the current study (), in general, the Latvian companies have a weak tendency to choose a business strategy that is based on a diversified range of products and services (the evaluation is 4.6 out of 7).

3.3.3. Exploitation of focus strategies

Various studies indicate that the most successful and fast-growing companies are the ones that do not ‘strive to service everybody', but rather focus on and become leaders in comparatively small market segments or niches (see Sauka, Citation2013; Sauka & Welter, Citation2012; Simon, Citation2009). Focussing on specific market segments usually ensures better contact with the customers and, thus, also higher awareness of their wishes and potential to satisfy them, which is definitely a pre-requisite for a competitive company. Porter (Citation1992) defines this orientation of a business strategy as a ‘focus strategy’ – this is one of the three possible success strategies to ensure the competitiveness of a business. The competitiveness study of the Latvian companies shows () that their strategies are at least slightly based on focussing on specific segments of the target market.

3.3.4. Cost leadership versus producing high value added

Next to the ‘focus strategy' the study also covered two other strategy elements that are important to business competitiveness: cost optimization and orientation towards product manufacturing or service provision with high added value. This focus of the business strategy is known as ‘cost leadership' and ‘differentiation' (Porter, Citation1990): in the first case companies will do their utmost to reduce product or service costs, thus ensuring competitiveness with the help of lower prices or higher profits. In the case of ‘differentiation', a company's competitiveness is based on products and/or services that are preferably difficult to copy or substitute, with a relatively high added value, and that the customers are ready to pay a higher price for.

According to the findings presented in the , the Latvian entrepreneurs do not have a particular preference for either ‘cost leadership' or ‘differentiation' strategy. The average indicator of such cost optimization elements as outsourcing, product standardization, or increase of the production volume is within 4.3–4.6 out of 7. Besides, companies do not really demonstrate tendencies to offer products or services with high added value (only 3.6 out of 7). Thus, considering the average results, we can conclude that in the case of the two strategies, the companies tend to choose ‘something in between': they do not focus on either cost leadership or high added value creation.

However, in order to come to these conclusions, we cannot rely on the average index alone. It is important to understand how the indicator is calculated, which in turn requires a more detailed data analysis. The data analysis is significant because the average result tells only about business strategies in general, and not about specific strategies that the surveyed business groups choose to implement to a greater or lesser extent. In this light, after having analysed separate business groups, the summarized data show that approximately similar number of the surveyed Latvian companies choose (or are forced to choose) to combine (a) comparatively high costs with offering low added value products or services in the market (i.e. both ‘cost leadership' and ‘high added value' have been evaluated within 1–3) or (b) medium costs with medium added value (the evaluation of both strategy aspects is 4). In neither of the cases, though particularly as regards the companies working with high costs and offering low added value, can we talk about very competitive operation of the firm.

One-third of the Latvian companies, however, choose to offer comparatively high added value products with low costs. However, according to Porter (Citation1990), such a choice of strategy, namely, a combination of ‘differentiation' and ‘cost leadership', is not preferable. Furthermore, in the long term it can lead to reduction in competitiveness; there are quite frequent cases in the market when companies manage to achieve even very successful results by offering high quality goods for comparatively low prices (e.g. Sauka, Citation2013). Nevertheless, as demonstrated by the results of the study, a minority of the Latvian companies are able to offer high added value and low costs in comparison with the two business groups mentioned above. All in all, the study results make us conclude that although the companies are slightly inclined to use the advantages of ‘focus strategies', and they assess quality of the available workforce and access to physical resources rather highly, competitiveness of the Latvian companies cannot be assessed positively due to the imbalance of costs and added value. The reason for that, most probably, is not the companies’ ‘free choice', but rather the use of these strategies ‘by force'. It means that, irrespective of the product's added value, grounds for the high end costs could be the high manufacturing and servicing costs due to, for example, technologies, property etc. purchased in 2007–2008 when the prices peaked, and not the entrepreneurs’ inefficiency in managing their businesses.

3.3.5. EO: innovativeness dimension

In addition to the factors affecting competitiveness of the Latvian companies mentioned above, there was another significant element of competitiveness included in the questionnaire – ‘EO'. EO is a tool that combines three strategy dimensions important for any successful business activity and it allows us to measure to what extent companies focus on innovations, operation, risk-taking, and proactivity. There is an increasing number of studies around the world proving that companies that are innovative, likely to accept greater, though well-considered, risks and proactive in their work with competitors, demonstrate much better performance and are, thus, more competitive (e.g. Moreno & Casillas, Citation2008; Rauch et al., Citation2009; Short et al., Citation2009).

According to the results of the study on competitiveness of the Latvian companies in a scale from ‘1' to ‘7', where ‘7' means an innovative firm, the average indicator for innovation in the Latvian companies fluctuates from 3.4 for the company's ability to create new, unique manufacturing processes and methods, as well as to carry out significant changes in products or services, to 3.9 for introduction of new products or services.

Similar to the ‘cost leadership' and ‘differentiation' strategies, it is important to understand how this average index is calculated. Thus, it is important to know the distribution, that is, if:

the innovation indicator of most of the Latvian companies is really close to 4, or, and this would be a relatively better news; or if

the average index is formed by a number of the Latvian entrepreneurs evaluating their innovation level close to 7 and a similar number of them – close to 1.

The study results provide us with at least a partial answer to the question indicating the following tendencies. First of all, concerning the introduction of new products, most of the surveyed Latvian companies evaluate this aspect either with ‘1' (very low level of innovation, approximately 27% respondents), or with ‘5' or ‘6' (comparatively high level of innovation, 17% and 23%, respectively). We can conclude that most of the Latvian firms are relatively innovative when it comes to introduction of new products.

3.3.6. Entrepreneurial orientation: risk taking and proactivity dimensions

According to the study results, similar to the innovation level, the average indices in the readiness to take risks of business orientation are within 3.5–3.6 in a scale from ‘1' to ‘7'. The Latvian company owner-managers demonstrated a slightly better result when it comes to the question of whether the ‘company strives to surpass others by introducing new ideas and products’) evaluating their business strategy in the light of proactivity. The findings show 4.0.

When analysing how the average index is formed, we come to the conclusion that, unlike innovation, the readiness of the Latvian companies to take risks is not close to either ‘1' or ‘7'. The evaluation is rather closer to ‘4' with a tendency to lean towards 1–3. A similar conclusion about the evaluation results concentrating on ‘4' can be drawn regarding the proactivity factor of business orientation – there is only a very weak inclination in the direction of 5–7 of the scale. Although this result, of course, is not entirely negative, however, the experience of other countries has proved (see, e.g. Rauch et al., Citation2009) that the present orientation of strategies does not indicate a high level of competitiveness (of the Latvian companies, in the present case). Thus, based on the results of this study, we might suggest that the Latvian companies reconsider if they should probably risk slightly more and take a more aggressive position in their work with competitors in order to improve their own situation in the local and foreign markets.

3.3.7. Key priorities of owner-managers

In addition to the evaluation of the existing strategy we asked the company owner-managers about the key priorities that they think should be introduced in order to become more competitive in the market. The findings are summarized in . According to the Latvian entrepreneurs, the highest priorities are to increase profit (5.8 out of 7), to increase the volume of sale in the Latvian market (5.2), to reduce costs (5.0), to improve the quality of products or services (4.8). Lastly, when analysing business strategies, we have to, of course, look at the companies’ orientation towards foreign markets, that is, the size of export. Based on the study, about 12–13% of the surveyed Latvian companies export 5–25% and a similar share export 26–50% of their total volume of sale. There are about 6% of companies whose exports reach even 51–75% and 76–95% (6.1% and 6.4%, respectively). We have to admit that this looks like a very good and promising tendency for business competitiveness.

3.4. Communication networks

It is well known that companies’ own resources, especially, for micro, small and medium enterprises, are very limited. Thus, in order to compete more successfully in the market, successful companies attract various resources from outside and they do it with little or no financial investment. One of the very effective and economical ways to attract external resources necessary to be competitive is successful use of the company contacts or in other words – communication networks.

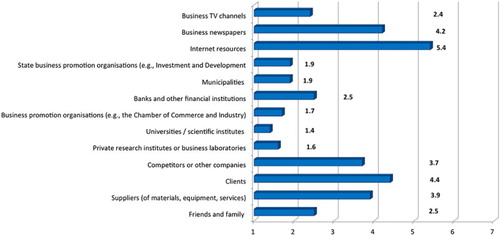

Communication networks can be used to attract very diverse resources that are significant in ensuring business competitiveness (see, e.g. Malecki & Veldhoen, Citation1993; Simon, Citation2009). For example, there are many fast-growing firms around the world, including in Latvia, that have proved that one can get useful and often free-of-charge information from suppliers, clients, and also competitors about any potential market tendencies – products that sell well or badly in specific markets, new trends for products, services, etc. (see Sauka, Citation2013; Sauka & Welter, Citation2008; Simon, Citation2009). As reflected by the results of this study, however, the Latvian entrepreneurs are not particularly active either in the use of this (the average result is 3.9–4.4 out of 7) or any other communication network.

According to our results (see ), the Latvian companies are especially inactive in: (a) cooperation with business laboratories (1.6 out of 7), universities and research institutes (1.4), which could be a potential resource for introduction of innovative, competitive products or services; (b) cooperation with organizations promoting entrepreneurship – both state owned (e.g. Investment and Development Agency of Latvia) (1.9) and non-governmental ones (e.g. Latvian Chamber of Commerce and Industry) (1.7) – which can be used not only to influence national processes in business policy (e.g. business legislation), but also to reach out to foreign markets. The surveyed Latvian companies have very little cooperation with municipalities (1.9), banks and other financial institutions (2.5), as well as friends and family (2.5) to attract free or very cheap resources. Similar to the information about clients, competitors, and suppliers, in order to gather information that is important for one's business the Latvian companies more often use business newspapers (4.2) and the internet (5.4).

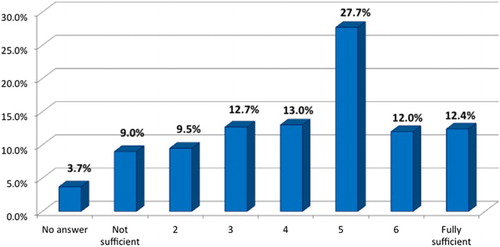

3.5. Financial resources

In order to introduce competitive business strategies, it is definitely not enough to use free or comparatively cheap communication networks. Companies’ access to financial resources has a crucial role in ensuring competitive business. According to our results, the Latvian entrepreneurs evaluate their access to financial resources slightly above 4 (4.3 out of 7). However, when analysing answers broken down into business groups, one can see that a slightly bigger share of the surveyed entrepreneurs are satisfied with the access to financial capital (see ). The results show that approximately 50% of the surveyed companies evaluate access to financial capital somewhere within 5–7 (where ‘7' means sufficient access to financial resources). Only a little more than 30% of companies have evaluated this factor within 1–3. Although, in general, this is not a very good indicator and we cannot refer to the Latvian business environment having a very good access to financial resources for companies; nevertheless, we have to admit that considering the overall economic situation in Latvia, this result shall not be interpreted as overly negative.

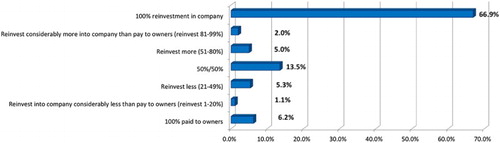

We included another question in the competitiveness survey of the Latvian companies with the aim to find out if they use the available financial capital (as well as human resources, physical resources, strategies, and others) efficiently in order to gain profit. Besides, we wanted to know what they do with the gained profit. It has to be said that the study results are pleasing as regards this specific indicator. Slightly more than 72% of the surveyed entrepreneurs reported that they made a profit last year. Moreover, approximately 70% of them reinvested the entire profit in their business, which definitely indicates a sustainable approach towards doing business (see ).

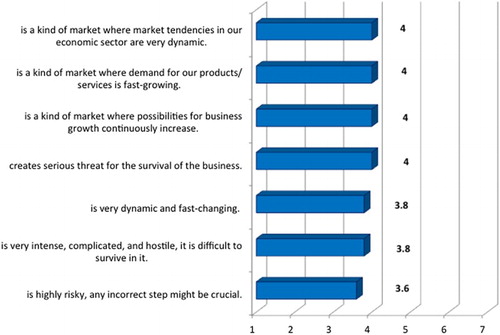

3.6. Influence of external environment

The results (see ) indicate that in general the surveyed entrepreneurs evaluate the influence of external environment on business competitiveness (or more precisely – the situation in the main markets where the company works) neither positively nor negatively. Taking into account the average index, we might conclude that the Latvian entrepreneurs do not look upon the influence of external environment as either too burdensome and threatening, or business friendly (the evaluation is 3.6–4.0 out of 7). When analysing the results in more detail, however, we see a slightly bigger share of the entrepreneurs who look upon the market as risky where every decision might turn out to be crucial (i.e. about 22% and 36% of the respondents evaluate this aspect with ratings of ‘2' and ‘3’, respectively). A similar negative tendency is observed as regards their assessment of the market dynamics, variability; more entrepreneurs are inclined towards assessment of the market as hostile where it is difficult to survive. According to the study results, there is marginally more positive tendency in the Latvian entrepreneurs’ evaluation of the market from the point of view of the growth of demand for the products on offer. In a similar vein, irrespective of the above mentioned rather negative tendencies, approximately half of the entrepreneurs think that the market has potential, that is, possibilities for business growth are on the increase.

3.7. Business activity in comparison to competitors

At the end, we asked the company owner-managers to evaluate their company activity as compared to that of the main competitors in the economic sector. Namely, the entrepreneurs were asked to compare the three key indicators of business activity: profit, turnover, and the number of employees, as well as the size of export and investments in the company.

According to the study results, when comparing their own activity with that of the competitors, the Latvian entrepreneurs rate themselves slightly below four (3.7–3.9, depending on the activity indicator). Thus, on average the Latvian entrepreneurs perform neither better nor worse than their competitors. When looking at the results in more detail, we found out that most of the surveyed entrepreneurs (39–41%, depending on the activity indicator) assessed their activity with a rating of ‘3' – thus, they think that their competitors work better. This detail in the study result surely leads to the question which companies are more competitive in the eyes of the respondents – are they Latvian or foreign, big or small? Unfortunately, the present study does not provide us with an answer to the question.

4. Conclusions

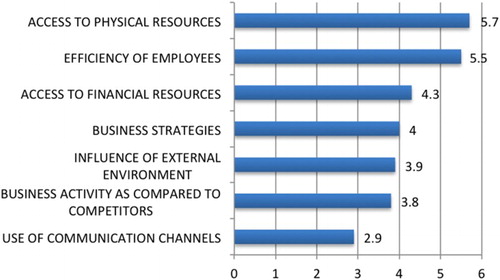

Assessment of the competitiveness of the Latvian companies in accordance with the study results is summarized in .Footnote2 The figure shows the average index of all the determinants of competitiveness included in the study of the Latvian companies. Namely, efficiency of employees has been calculated taking the simple average from answers to questions in each of the blocks of the questionnaire form as described in Section 2.

Figure 10. Competitiveness assessment of the Latvian entrepreneurs: average indices assessment scale: ‘1' uncompetitive companies; ‘7' very competitive; n = 410.

According to the results, the indicator that is, on average, least used by the Latvian entrepreneurs to promote competitiveness, is communication networks. In a scale from ‘1' to ‘7', where ‘1' means low, but ‘7' is very high as regards use of the concerned element in doing business, communication networks were evaluated at ‘2.9'. This result proves that to strengthen competitiveness the Latvian companies should pay much more attention to cooperation with universities and other research institutions, suppliers, and clients, as well as organizations promoting entrepreneurship.

Operation evaluation in comparison with competitors alone reflects the level of competitiveness of the Latvian companies and it is evaluated slightly above the middle index: 3.8 in a scale from ‘1' to ‘7'. The Latvian entrepreneurs have given a similar evaluation of just above the middle index (3.9) to the influence of external environment – it describes how favourable or unfavourable for doing business is the market where the company operates. Competitiveness of the companies is hugely determined by their ability to plan and implement business strategies. The average results of the study (4.0) prove that many companies need to reassess their choice of strategies. In particular, when it comes to both orientation towards ‘cost leadership’ or ‘differentiation’, and ‘risk-taking’ and ‘proactivity’ it would be useful for at least some of the Latvian companies to reassess their strategies in order to increase their competitiveness in export markets.

The Latvian companies have shown a slightly better result, 4.3 out of 7, in evaluating access to financial capital, which means that there is a lot to do in the area, especially, on the part of the policy-makers and financial institutions (see Sauka & Welter, Citation2011). The efficiencies of the Latvian entrepreneurs in using their employees and access to physical resources as a contribution to the overall competitiveness have been evaluated relatively higher with ‘5.5' and ‘5.7’, respectively.

In general, in accordance with the study results on competitiveness of the Latvian companies, the Latvian entrepreneurs perceive they have sufficient potential to use various promotional tools for business more actively, in particular, specific business strategies and communication networks.Footnote3 However, considering the ability to profit of most of the Latvian entrepreneurs, as well as their orientation towards export markets and use of the physical resources, the study results give reasonable hope that the Latvian companies will develop in the right direction.

As a result, we hope that the study on competitiveness of the Latvian companies will be a useful source of information for Latvian entrepreneurs, among other things, in reassessing business strategies in order to take the right decisions leading to business growth. As for the policy-makers, the key message in the current study is rather clear: it is important to continue active work towards improved common business environment – business infrastructure, including access to financial capital, and, as proved by other studies, (e.g. Sauka & Putniņš, Citation2011), also quality and consistency of the tax policy.

The main shortcoming of this study is, arguably, its descriptive nature. Namely, the study only identifies various factors that potentially can contribute to the competitiveness of the firm but does not say anything about how various drivers of competitiveness could be combined in order to increase firm profits. A qualitative approach would be required to determine interactions of these factors, which is one of the areas for further studies on competitiveness of the firms. Apart from this, other such studies could also develop more knowledge on which factors are, in general, more important than others. In the context of this study, such information would be crucial in order to add weights to various indicators when calculating an average – apart from taking a simple average. The results might also be context specific and should be interpreted with caution when applied to countries with more developed market economies, such as those in the ‘old EU’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributor

Arnis Sauka is an assistant professor and director of the Centre for Sustainable Business at SSE Riga. At the beginning of 2008 Arnis Sauka earned a Dr rer pol from the University of Siegen (Germany). Prior to that, Arnis was a visiting Ph.D. candidate at Jönköping International Business School (Sweden) and a teaching fellow at SSEES/University College London (U.K.). His main research interests include productive and unproductive entrepreneurship; business start-ups, growth and exits; entrepreneurship policy making; entrepreneurship in transition context.

Notes

1. Available from the author upon request.

2. Regression results showing the influence of these factors on the company profit and other performance indicators are available upon request from the author.

3. Unfortunately, due to the lack of data we cannot evaluate efficiency of use of these factors in the Latvian companies as compared to companies in other countries.

References

- Alvarez, S., & Busenitz, L. (2001). The entrepreneurship of resource-based theory. Journal of Management, 27, 755–775. doi: 10.1177/014920630102700609

- Baker, W., & Sinkula, J. (2009). The complementary effects of market orientation and entrepreneurial orientation on profitability in small businesses. Journal of Small Business Management, 47, 443–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-627X.2009.00278.x

- Baltrušaitytė-Axelson, J., Sauka, A., & Welter, F. (2008). Nascent entrepreneurship in Latvia. Evidence from the panel study of entrepreneurial dynamics 1st wave. Riga: Stockholm School of Economics in Riga.

- Bantel, K., & Jackson, S. (1989). Top management and innovation in banking: Does the composition of the top management team make a difference? Strategic Management Journal, 10, 107–124. doi: 10.1002/smj.4250100709

- Becchetti, L., & Trovato, G. (2002). The determinants of growth for small and medium sized firms. The role of the availability of external finance. Small Business Economics, 19, 291–306. doi: 10.1023/A:1019678429111

- Benkovskis, K. (2002). Competitiveness of Latvia's exporters. Baltic Journal of Economics, 12(2), 17–45. doi: 10.1080/1406099X.2012.10840516

- Bougheas, S. (2004). Internal vs external financing of R&D. Small Business Economics, 22, 11–17. doi: 10.1023/B:SBEJ.0000011569.79252.e5

- Buzzigoli, L., & Viviani, A. (2009). Firm and system competitiveness: Problems of definitoon, measurement and analysis. In A. Viviani (Ed.), Firms and system competitiveness in Italy (pp. 11–37). Firenze: Firenze University Press.

- Covin, J., & Slevin, D. (1989). Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments. Strategic Management Journal, 10, 75–87. doi: 10.1002/smj.4250100107

- Davidsson, P. (2006). Nascent entrepreneurship: Empirical studies and developments. Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 2, 1–76. doi: 10.1561/0300000005

- Dess, G., & Beard, D. (1984). Dimensions of organizational task environments. Administrative Science Quarterly, 29, 52–73. doi: 10.2307/2393080

- Gilley, K., & Rasheed, M. (2000). Making more by doing less: An analysis of outsourcing and its effect in firm performance. Journal of Management 26, 763–790. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2063(00)00055-6

- Gimeno, J., Folta, T., Cooper, A., & Woo, C. (1997). Survival of the fittest? Entrepreneurial human capital and the persistence of underperforming firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42, 750–783. doi: 10.2307/2393656

- Greve, A., & Salaff, J. (2003). Social networks and entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(1), 1–22. doi: 10.1111/1540-8520.00029

- Hambrick, D., & Mason, P. (1984). Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Academy of Management Review, 9, 193–207.

- Hamermesh, R., Marshall, G., & Pirmohamed, T. (2002). Note on business model analysis for the entrepreneur. Retrieved February 20, 2011, from Harvard Born Globals 38/50 Business Review, http://hbr.org/product/note-on-business-model-analysis-for-the-entreprene/an/802048-PDF-ENG

- Hitt, M., Bierman, L., Shimizu, K., & Kochhar, R. (2001). Direct and moderating effects of human capital on strategy and performance in professional service firms: A resource based perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 44, 13–28. doi: 10.2307/3069334

- Hoang, H., & Antoncic, B. (2003). Network-based research in entrepreneurship. A critical review. Journal of Business Venturing, 18, 165–187. doi: 10.1016/S0883-9026(02)00081-2

- Hughes, M., & Morgan, R. (2007). Deconstructing the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and business performance at the embryonic stage of firm growth. Industrial Marketing Management, 36, 651–661. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2006.04.003

- Ibeh, K. (2003). Toward a contingency framework of export entrepreneurship: Conceptualisations and empirical evidence. Small Business Economics, 20, 49–68. doi: 10.1023/A:1020244404241

- King, A., & Tucci, C. (2002). Incumbent entry into new market niches: The role of experience and managerial choice in the creation of dynamic capabilities. Management Science, 48, 171–186. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.48.2.171.253

- Kitson, M., Martin, R., & Tyler, P. (2004). Regional competitiveness: An elusive yet key concept? Regional Studies, 38(9), 991–999. doi: 10.1080/0034340042000320816

- Knight, G., & Cavusgil, S. (2005). A taxonomy of born global firms. Management International Review, 45(3), 15–35.

- Kreiser, P., Marino, M., & Weaver, K. (2002). Assessing the psychometric properties of the entrepreneurial orientation scale: A multi-country analysis. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 26(4), 71–95.

- Malecki, E., & Veldhoen, N. (1993). Network activities, information and competitiveness in small firms. Geografiska Annaler. Series B, Human Geography, 75(3), 131–147. doi: 10.2307/490931

- Man, T., Lau, T., & Chan, K. (2002). The competitiveness of small and medium enterprises. A conceptualization with focus on entrepreneurial competencies. Journal of Business Venturing, 17, 123–142. doi: 10.1016/S0883-9026(00)00058-6

- McKelvie, A., & Davidsson, P. (2009). From resource base to dynamic capabilities: An investigation of new firms. British Journal of Management, 20, S63–S80. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8551.2008.00613.x

- Miller, D. (1983). The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms. Management Science, 29, 770–791. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.29.7.770

- Miller, D., & Friesen, P. (1982). Innovation in conservative and entrepreneurial firms: Two models of strategic momentum. Strategic Management Journal, 3, 1–25. doi: 10.1002/smj.4250030102

- Moreno, A., & Casillas, J. (2008). Entrepreneurial orientation and growth of SMEs: A causal model. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32(3), 507–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6520.2008.00238.x

- Mudambi, R., & Zahra, S. (2007). The survival of international new ventures. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(2), 333–352. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400264

- Nelson, R. (1992). Recent writings on competitiveness: Boxing the compass. California Management Review, 34(2), 127–137. doi: 10.2307/41166697

- Pissarides, F. (1999). Is lack of funds the main obstacle to growth? EBRD's experience with small- and medium-sized businesses in Central and Eastern Europe. Journal of Business Venturing, 14, 519–539. doi: 10.1016/S0883-9026(98)00027-5

- Porter, M. (1990). The competitive advantage of nations. New York: Free Press.

- Porter, M. (1992). Competitive advantage: Creating and sustaining superior performance. Issue 10. London: PA Consulting Group.

- Porter, M. E., & Ketels, H. M. C. (2003). UK competitiveness: Moving to the next stage, DTI economics Paper 3. London: Department of Trade and Industry.

- Rauch, A., Frese, M., & Utsch, A. (2005). Effects of human capital and long-term human resources development and utilization on employment growth of small-scale businesses: A causal analysis. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29, 681–693.

- Rauch, A., Wiklund, J., Lumpkin, T., & Frese, M. (2009). Entrepreneurial orientation and business performance: An assessment of past research and suggestions for the future. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33, 761–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00308.x

- Robson, P. J. A., & Benett, R. J. (2000). SME growth: The relationship with business advice and external collaboration. Small Business Economics, 15, 193–208. doi: 10.1023/A:1008129012953

- Roper, S. (1998). Entrepreneurial characteristics, strategic choice and small business performance. Small Business Economics, 11, 11–24. doi: 10.1023/A:1007955504485

- Sauka, A. (2008). Productive, unproductive and destructive entrepreneurship: A theoretical and empirical exploration. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang GmbH.

- Sauka, A. (2013). Hidden champions from Latvia. In P. McKiernan & D. Purg (Eds.), Hidden champions in CEE and turkey- Carving out global niche (pp. 219–244). Cham: Springer.

- Sauka, A., & Welter, F. (2008). Taking advantage of transition: The case of safety Ltd. in Latvia. In R. Aidis & F. Welter (Eds.), The cutting edge: Innovation and entrepreneurship in new Europe (pp. 111–128). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Sauka, A., & Welter, F. (2011). Mentalities and mindsets – The difficulties of entrepreneurship policies in the Latvian context. In F. Welter & D. Smallbone (Eds.), Handbook of research on entrepreneurship policies in central and Eastern Europe (pp. 83–101). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Sauka, A., & Welter, F. (2012). MADARA case. In D. Kariv (Ed.), Female entrepreneurship and the new venture creation. An international overview (pp. 469–475). Routledge: Female Entrepreneurship.

- Short, J., Broberg, J., Cogliser, C., & Brigham, K. (2009). Construct validation using computer- aided text analysis (CATA): An illustration using entrepreneurial orientation. Organizational Research Methods. doi:10.1177/1094428109335949

- Simon, H. (2009). Hidden champions of the 21st Century. Success strategies of unknown world market leaders. New York: Springer.

- Subramaniam, M., & Youndt, M. (2005). The influence of intellectual capabilities on the types of innovative capabilities. Academy of Management Journal, 48, 450–463. doi: 10.5465/AMJ.2005.17407911

- Waheeduzzaman, A. N. M., & Ryans, J. J., Jr. (1996). Definition, perspectives, and understanding of international competitiveness: A quest for a common ground. Competitiveness Review, 6(2), 7–26. doi: 10.1108/eb046333

- Wright, P., Perris, S. P., Hiller, J. S., & Kroll, M. (1995). Competitiveness through management of diversity: Effects on stock price valuation. Academy of Management Journal, 38(1), 272–287. doi: 10.2307/256736

- Zahra, S., & Covin, J. (1993). Business strategy, technology policy and firm performance. Strategic Management Journal, 14, 451–478. doi: 10.1002/smj.4250140605