?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Fiscal forecasts produced by international institutions came under strong criticism after the Eurozone sovereign debt crisis due to excessive optimism. Presently, international organizations are also accused of applying a double standard. Their opponents claim they depict negative picture for populist governments. This paper evaluates forecasts provided by the IMF, European Commission and the OECD based on a panel of EU economies and selected large countries. Five years after the Sovereign debt crisis, we still find excessively optimistic forecasts for Portugal and Spain. Moreover, the EC and OECD are being indulgent to countries under the excessive deficit procedure. There is also a strong autocorrelation of forecast errors and cyclical biases – European Commission overestimates governments’ propensity to tighten fiscal policy during expansion and forecasts an overly pessimistic picture during a slowdown. However, we find no evidence suggesting that fiscal forecasts stigmatize the governments accused of populism.

1. Introduction

The problem of fiscal forecast accuracy plays a relevant role in the European Union (EU) countries. According to the Stability and Growth Pact, member states are obliged to keep their government fiscal deficits under 3% of gross domestic product (GDP) and public debt below 60% of GDP. Furthermore, each country is obliged to achieve the so-called medium-term objective (MTO) – a desired level of structural balance dependent on the nominal GDP growth rate, interest rates, etc. In case when countries do not comply European Commission (EC) invokes so-called Excessive deficit procedure (EDP). Under its corrective arm government are obliged to reduce imbalance, otherwise EC imposes financial sanctions, e.g. freeze of EU funds or financial penalties up to 0.5% of GDP. Public finances are also monitored by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), but their recommendations are less binding.

The competences of international supervision of public finances are systematically increasing, not without controversy. The process of forecasting the financial situation cannot be fully separated from the political agenda. International institutions sometimes have contradictory goals comparing to the national governments what may rise conflicts. Our aim is to determine whether, in such cases, international institutions systematically tend to apply different standards in the assessment of public finances for two certain groups of governments. The first group can be described as populist governments. It includes Polish PiS, Hungarian Fidesz and Romanian PSD (Italian M5S-LN government rule was too short to correctly measure its effects). We refer here to the definition of populism which is currently applied by a mainstream European press (see e.g. Guardian (Citation2018) and BBC (Citation2019)). This concept surpasses the traditional definition assuming a more expansive fiscal policy, which is applicable for Romanian PSD government only. In the EU, new populism is rather related to Euroscepticism and controversial institutional policy, i.e. both the Polish PiS and Hungarian Fidesz are accused of violating the rule of law by the European Parliament. The second group describes indebted Mediterranean economies, i.e. Spain, Italy and Portugal. We apply a panel study to verify this hypothesis, where government-specific errors will be represented by dummy variables.

Our research shows no strong evidence suggesting that fiscal forecasts stigmatize governments accused of populism or violating the rule of law. On the other hand, international institutions do tend to be more lenient to indebted countries such as Portugal, Spain and Italy. In the case of the EC and the OECD, the bias was also greater for economies under the corrective arm of the EC EDP. In addition, there are cyclical problems related to long-term forecasts for emerging European economies: the EC tends to overestimate the propensity to consolidate public finances during expansion and presents an overly pessimistic picture during a slowdown. Finally, we also found a strong serial correlation between forecast errors.

This paper is structured as follows. The next section discusses political clashes related to EU financial framework. Section 3 provides an in-depth literature on the fiscal forecast accuracy. Section 4 describes the forecasting procedures of international institutions and the content of our datasets. Section 5 presents the methodology of our research. Section 6 discusses our empirical results. Finally, section 7 concludes the paper.

2. Literature Review – political clashes over the EU fiscal framework

This section provided a quick overview of the political clashes regarding reforms of financial framework in the EU and the international supervision.

First of all, there is no economic consensus on the outcomes. While some authors claim that EDP recommendations help to consolidate fiscal policy in the indebted countries (De Jong & Gilbert, Citation2020), others highlight the lack of instrument in the toolbox of international institutions to improve public finances in the countries which do not cooperate (Reuter, Citation2015; Schuknecht et al., Citation2011). Finally, some authors directly undermine the credibility of European fiscal rules and the international supervision of the IMF and OECD (Belke, Citation2017) after the European sovereign debt crisis using the following arguments: first, the fiscal forecast overestimated the governments’ ability to consolidate public finances in indebted Portugal, Italy and Spain. Second, the EC selectively released France, Portugal and Spain from the sanctions, what motivates other countries to a non-compliance with the fiscal rules.

The subsequent reforms of the fiscal framework provided mixed results. European fiscal board (EFB, Citation2020) highlighted that majority of the EU countries reduced deficit, but did not lower public debt and failed to build enough fiscal reserves for a downturn. Also, the response to the financial reform was not homogenous across the EU. On the one hand, countries with healthy public finances, such as Germany or the Netherlands are showing strong support to the fiscal discipline. On the other, countries which perform worse like France, Italy or Spain are prone to wage ‘war of attrition’ – national political groups are resisting fiscal adjustments until it is clear that some other group will pay its cost (Doray-Demers & Foucault, Citation2017).

The drawback of this strategy is the increasing criticism of financial framework in the countries with weaker fiscal discipline, which especially intensified in the recent years. The political fragmentation in the EU (see, e.g. Gidron & Hall (Citation2017)) has led also to strong accusations of applying a double standard toward favored and unfavoured national governments. What was probably the most vocal clash occurred between Italy and France (Reuters, Citation2018). The EC forced the Italian government to lower its expected deficit for 2019 from 2.4% of GDP to 2.04%. At the same time, France was allowed to temporarily exceed the 3% threshold to fulfill promises pledged to the Yellow Jackets movement (fr. Gilets Jaunes). The deputy prime minister of Italy, Matteo Salvini, publicly denounced the approach of French commissioner, Pierre Moscovicci.

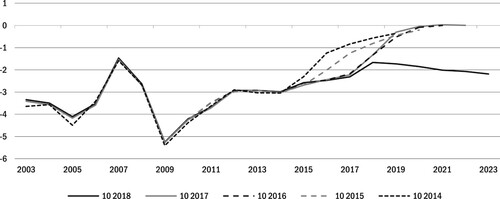

The reverberation of this conflict was also visible in the deficit forecast of the IMF. Despite Lega Nord-Five Star Movement declarations that they would lower the deficit after 2019, the IMF analysts predict constant deterioration. This assessment of IMF might be correct (finally governing coalition collapsed), especially given the costly pledges of, e.g. universal income, lower VAT and lower retirement age. However, during the previous Renzi government in Italy, the IMF frequently and consistently provided overly optimistic forecasts, despite the worsening realities of the government budgets. The evolution of the IMF forecasts for Italy in the last five years is presented in . The errors in the forecasts in the previous years could undermine the credibility of the institution.

Figure 1. IMF deficit forecast for Italy – World Economic Outlook (WEO) October Editions. Each line represents forecasts available in different years. The 2018 edition (black solid line) provides up to date estimate of 2017 government deficit and forecast from 2018 to 2023. Source: IMF WEO database.

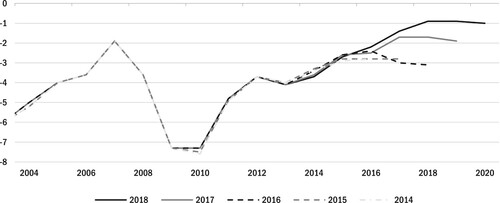

Another interesting example is Poland. Since 2016, the PiS (Law and Justice) government has been in open conflict with the EC regarding the rule of law, and the EC has, for two consecutive years, reduced the expected deficit in their forecast (). The problem is complex. The ruling party introduced generous social programs and, at the same time, successfully improved the collection of tax revenues (Poniatowski et al., Citation2018). This increase in revenues was hardly predictable. Furthermore, if the tax collectors had been unsuccessful, more negative scenarios would have been likely. The literature on this subject highlights the negative link between damage to institutional quality and attachment to disciplinary fiscal rules (Wyplosz, Citation2012). Therefore, more cautious forecasts could be proof of responsibility. If the EC absolutely trusted the governmental forecasts and PiS failed to improve collection, the institution would expose the bondholders to the greater credit risk.

Figure 2. EC deficit forecast for Poland – Winter Editions. Source: EC forecast – statistical annex.

Mentioned examples showed only few dilemmas faced by the international institutions. Macroeconomic projections are often compared between the countries. Therefore, forecasting frameworks need to maintain some consistency of the errors. Permanent biases are likely to undermine credibility of the international supervision. The next section will show these problems were very urgent in the past, especially in case of sovereign debt crisis. Our aim is to verify whether situation improved since that time.

3. Literature Review – fiscal forecasting

This section provides an insight into the subject of fiscal situation forecasting performance and its institutional implications. Debate on the topic effectively started at the beginning of the new millennium. Short-term estimates of current year deficits (as a percentage of GDP) provided by international financial institutions such as the OECD or the IMF came under severe criticism, as they were frequently less accurate than the consensus of professional forecasters (Batchelor, Citation2001; Pons, Citation2000). Furthermore, some authors highlighted the lack of statistical efficiency and inconsistency of forecasts for G8 countries (Artis & Marcellino, Citation2001); there were examples of countries where a significant positive (Japan, Italy) or negative (Canada) forecast bias occurred. This phenomenon was explained by an ‘asymmetrical loss function’ in countries where deficit forecasts were politically sensitive, in other words, due to implementation of new fiscal policies, international institutions tended to provide cautious estimates.

The accuracy of forecasts prepared by public institutions likely improved within the next five years or greater interest was related to the long-term forecasts. As a result, the topic of the difference between the forecasts of international agencies and government institutions began to dominate in the literature. According to the majority of authors, deficit forecasts prepared by national governments suffered from political motivations. Their performance was less accurate, despite the use of superior information which is not available outside the ministries of finance or other budgeting entities (Brück & Stephan, Citation2006; Jonung & Larch, Citation2006; Leal et al., Citation2008; Merola & Pérez, Citation2013).

Positive bias in governments forecasts has been rationalized. In contrast to international agencies, government entities can use detailed information on tax collection or planned expenditures. At the same time, politicians have strong motivations to present overly optimistic macroeconomic forecasts (in comparison to future realizations) and to depict success stories of their current policies, for instance, by presenting remarkably strong GDP growth or high wage dynamics, and neglecting to include high unemployment rates (Brück & Stephan, Citation2006). Moreover, such forecasts are prone to the political cycle—governing parties have the temptation to increase spending and boost consumption prior to elections to influence the voting outcome. In order to prevent misleading of stakeholders (e.g. bond holders, societies), academics highlight the need for international supervision of fiscal policies (Jonung & Larch, Citation2006).

Unfortunately, research on fiscal supervision and forecast accuracy suggests that external forecasts are also prone to the previously mentioned problems. Some authors (Leal et al., Citation2008; Merola & Pérez, Citation2013) have confirmed the supremacy of the EC/IMF over national agencies in accurately predicting outcomes of economic policies in the G8 space. But their analyses also confirmed the existence of the same problems typically seen in the governments’ projections including systematic positive bias and the existence of the influence of political cycles in the forecasts’ errors. In addition, the authors highlighted another problem: the forecast errors of national governments and international institutions tend to be correlated with each other. These findings likely imply overconfidence of the external forecasters in the information provided by national authorities.

Another strong critique of independent agencies’ forecasts came after the European sovereign debt crisis. The example of Greece prior to the introduction of ECB–EC–IMF economic adjustment programs provides a situation where both the EC and the IMF consistently maintained forecasts suggesting prompt deficit reduction, despite that country having missed selected targets, year after year, even prior to the crisis. Furthermore, Greece was able to mislead both economists from the EC and statisticians from Eurostat about its real economic performance.

Beetsma et al. (Citation2013) and Frankel & Schreger (Citation2013) pointed out that the Greek case was not the only one where the forecast failed to describe reality. The fiscal projections of EC tended to present overly rapid fiscal consolidation in EU countries under corrective arm of the EDP. Furthermore, the problem of over-optimistic forecasts has not been evident in other developed economies with even larger deficits (i.e. the U.S.A. and Japan). Thus, the problem of bias was not related, for example, to government investment activity, but rather to overconfidence in the corrective action of EDP procedure (Pina & Venes, Citation2011).

4. International deficit forecasts

This section describes the dataset used in this research. Government deficit/surplus forecasts are published semiannually by international institutions. Our first data source is the IMF World Economic Outlook report (WEO), published in April and October. There are also two interim rounds of forecast updates (in January and July), where only new GDP growth estimates are published.

The IMF’s database published simultaneously with the report contains information for 194 countries. We selected 36 of these to construct our sample. The selected countries include EU and OECD members, as well as other large non-OECD economies (e.g. China, Russia).

The data used is from 2008 to October 2018 (last release at the moment of writing). Prior to this period, the IMF did not report deficit forecasts for some of the emerging European economies of interest (e.g. the Czech Republic, Poland). The database contains information about government net lending or borrowing expressed as a percentage of GDP. Amongst macroeconomic variables, we use information about the annual dynamics of GDP growth, its deflator, and the Consumer Price Index (CPI). We also use time series of the current account balance as a percentage of GDP to account for the twin deficit theoremFootnote1 (Corsetti & Müller, Citation2006; Piersanti, Citation2000).

Each forecast covers a five-year horizon. We analyzed estimates for the current year (i.e. when the report was published) called ‘nowcasts’ and for the next three years. For example, from the report published in April 2015, we collected the nowcast estimate for 2015 and the estimates for 2016, 2017, and 2018 only.

The next source of data is the EC forecasts. Similar to the IMF, the EC also revises its forecasts twice per annum and provides two interim rounds where GDP forecasts are updated. The deficit forecasts are published during the spring and autumn (usually in April–May and November). The database contains information for 27-member states, the United Kingdom, the U.S.A., and Japan. We decided not to use information regarding candidate countries (e.g. Turkey) due to a short history, inconsistent reporting, and missing forecasts.

The number of indicators provided by the EC is greater than the number in the IMF reports. Statistical annexes also include information regarding the detailed structure of GDP, including public and private consumption expenditure, or gross fixed capital formation. Furthermore, labour market indicators include compensation of employees.

The EC forecasts also have a much shorter horizon of two years. In the spring round, the institution provides estimates for the current and next years. In the autumn round, estimates with a two-year horizon are also available. For example, the report published in November 2015 contained forecasts for 2015, 2016, and 2017. The horizon did not change in the next spring release, which provided information for 2016 and 2017.

Finally, we also use OECD economic outlook forecasts. The procedure of the update is semiannual and similar to that of the EC, but forecasts are published later compared to the IMF and EC (i.e. in May and December). The number of macroeconomic variables provided by the OECD is the same as in the report produced by the EC. The database contains information about: GDP, private and public consumption forecasts, CPI inflation and various price deflators, current account balances, and compensation of employees. The OECD produces forecasts for a similar horizon to the EC and shorter than the horizon of the IMF.

We excluded economies with episodes of adjustment bailout programs (i.e. Greece, Cyprus) as international institutions have capability to shape fiscal policy there. Secondly, less accurate forecasts for Greece may result from the lack of reliable times series, describing public finances up to 2016 as Greek authorities intentionally falsified statistics prior the Eurozone Sovereign Debt crisis. There were also periods when some international institutions did not publish forecasts for Greece and this fact created breaks in the analyzed time series. We also excluded small open economies with severe banking crises (i.e. Ireland, Iceland, and Slovenia). Such episodes create obvious outliers, which do not provide reliable information about performance of the major economies in the EU. The summary of investigated countries is presented in .

Table 1. Countries used in the panel by the international institution from which the data were sourced.

5. Methodology

The aim of our analysis is to verify whether international financial institutions provide biased forecasts in relation to the different EU countries. We repeat the calculations previously used in the literature (Artis & Marcellino, Citation2001; Brück & Stephan, Citation2006; Pina & Venes, Citation2011). The starting point for our analysis is the following model:

(1)

(1) where

is a final realization of the deficit in year t,

describes a forecast for year t prepared in the horizon h. For example, when h = 2, this indicates a forecast prepared two years prior to data realization.

If the forecasts are unbiased, the parameter should be statistically insignificant and

equal to one. Therefore, all forecast errors should be well described by random disturbances

. We assume there is no multiplicative error in the forecasts and that a1 = 1. Therefore, Equation (1) is transformed into:

(2)

(2) Next, we attempt to identify the factors, which may explain forecast errors. First, fiscal forecasts related to revenue collection depend on the realization of macroeconomic assumptions regarding GDP growth and its structure (e.g. private consumption and gross fixed capital formation), inflation, and wages. Second, the data on both fiscal revenues and expenditures are prone to revisions, such as in the process of consolidation of public sector finances. As a result, forecasters are sometimes preparing their estimates based on incomplete information about the current state of public finances. This phenomenon should result in systematic and different errors between the countries, as data collection and revision procedures may vary. To account for these problems, we expand Equation (2) to:

(3)

(3) where

stands for the error of financial institutions’ forecast

,

describes the vector of macroeconomic assumptions,

measures the magnitude of previous year deficit revisions between the moment when the forecasts were formulated and their final values. Also,

,

,

, and

are estimated parameters, and

is the equation residual. We introduced the third power of macroeconomic assumptions error to reflect stronger deficit increases during more severe downturns. We rejected to use second power in order to distinguish between positive and negative surprises. In the case of unbiased forecasts, parameter

should be equal to 0 (statistically insignificant). Parameters describing macroeconomic variables

and

are expected to be positive, for example, better activity, labour market conditions, or higher inflation should result in lower deficits.

As the next step, we introduce control variables describing both political and institutional factors. We use a panel structure to derive both cross-country and period fixed effects. Then we add variables describing whether the EC opened excessive deficit procedure against the country , whether World Bank governance indicators describe the government as dedicated to preserving the rule of law

, and whether the government is described as populist (or Eurosceptic) by the mainstream European press (e.g. Guardian, Citation2018; BBC, Citation2019 -

). Five separate dummies take positive value when they describe one of governments being in power: Polish PiS, Romanian PSD, Italian M5N and Lega Nord coalition and Hungarian Orban’s Fidesz and negative otherwise.

Due to the positive result of the test for autocorrelation, we also include the deficit forecast error for the horizon h related to previous reports . In Autumn reports

and

describe the same year. For example, for a report published in 2018

refers to 2019 in case of both reports. In case of Spring reports the approach is slightly different – we compare errors for the previous year. For example, horizon

denotes 2019 for a report published in Spring 2018. We compare it to the Autumn report published in 2017 where

denotes 2017 and

2018.

The final equation has following form:

(4)

(4) where

is a cross-country effect and

is a period effect. Our hypothesis states that values of

are skewed regionally. Furthermore, we expect the parameters corresponding to political variables to be statistically significant.

Secondly, for a robustness check we will also directly test the significance of the two dummy groups: populist and Mediterranean economies, based on the pooled data without the corresponding fixed effects.

(5)

(5) In both cases, we are using White’s diagonal method to achieve standard errors, that are robust to observation-specific heteroscedasticity in the disturbances, but not to correlation between residuals for different observations. The equations presented in are the result of this estimation. We also repeated the computation with White’s period method, which assumes that the errors for a cross-section are heteroskedastic and serially correlated (cross-section clustered). The modification of estimation techniques does not alter the final conclusions.

Table 2. International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecast errors – estimated models.

Table 3. European Commission (EC) forecast errors – estimated models.

Table 4. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) forecast errors – estimated models.

Table 5. Cross-country fixed effects – a summary.

6. Estimation results

This chapter presents a summary of the outcomes of our research. The full detailed estimates of the fixed effects panel models are available in . The results of pooled regressions are present in .

Table 6. Pooled regressions – forecast errors for the IMF.

Table 7. Pooled regressions – forecast errors for the European Commission.

Table 8. Pooled regressions – forecast errors for the OECD.

The estimated models indicate three negative phenomena visible in the evaluated forecasts. First and least troublesome – each of the international institution forecasts has a systematic negative bias (forecasts are more pessimistic comparing to further realizations): the parameter is non-zero and is statistically significant in the present and next year horizons. The largest bias is present in the EC case and amounts, respectively, to 0.28 and 0.47pp (percentage points). The OECD systematically provides overly optimistic forecasts for the current year (T0) by 0.32pp, but bias is lower in the one-year horizon (0.16pp). Finally, the bias presented in forecasts provided by the IMF is the lowest and equals, respectively, 0.10pp and 0.17pp. Our findings are contrarian to the previous literature on this subject. Researchers for G8 countries reported positive bias, e.g. Beetsma et al. (Citation2013) and Frankel & Schreger (Citation2013). There are two plausible reasons behind this phenomenon. First of all, this Eurozone sovereign debt crisis resulted in the increased scope of the fiscal supervision – authors (Beetsma et al., Citation2019) show that introductions of fiscal councils help to limit optimistic bias. Secondly previous research was conducted mainly for advanced economies, what might distort the overall picture.

Second, the forecast errors of government deficits are not randomly distributed; estimates are prone to autocorrelation problems. Therefore, we inserted an autoregressive component in each equation. In each case, these parameters were statistically significant. The values of this beta parameter were highest in the IMF case – close to 0.5 for each forecast horizon. Beta estimates for the OECD and EC cases were lower and more dispersed (equal to 0.22–0.47).

Third, the cross-section fixed effects were statistically significant in nearly every equation. In the EU, overly optimistic forecasts are particularly visible for Portugal and Spain, and, in the case of long-term estimates, for Italy. On the other hand, the improvement of fiscal balance after the global financial crisis was underestimated for Denmark and the Czech Republic. For countries outside the EU, the European-based institutions (EC and OECD) tend to present overly optimistic estimates regarding the U.S.A.

Amongst the macroeconomic variables, we identified a strong relationship between errors of deficit forecast and GDP growth assumption or its components, such as private consumption or gross fixed capital formation. Our analysis provides negative and statistically significant parameters for the third power in the EC forecasts. In the majority of horizons, the effect is not strong. For example, the 3pp positive surprise in the consumption dynamics (i.e. dynamics of indicator is 3 percentage point higher comparing to the forecast) results in a higher deficit forecast error by 0.1pp for nowcasts and one-year forecasts made by the EC. A more severe problem occurs in cases of horizons longer than two years, where the response is equal to 0.6pp. This observation shows that the EC tends to overestimate the propensity of national governments to consolidate public finances. Similarly, during a slowdown, forecasts are likely to provide an overly pessimistic picture.

Surprisingly, we see no coincidence between current account balances and government deficit forecast errors, even for long-term forecasts. The institutions forecast does not reflect propensity to simultaneous increase of external and fiscal deficit, despite strong macroeconomic foundations.

In line with the findings of Pina & Venes (Citation2011), we found evidence that the OECD and EC are overconfident in the positive effect of EDP corrective arm. The current year forecasts are optimistically biased by, respectively, 0.5pp and 0.3pp. In the case of the EC, this bias can lead to premature decisions regarding closing of the procedure.

The pooled regressions confirm conclusions from the fixed effects panel models. The forecast for Mediterranean economies were on average too optimistic by approximately 0.3pp in case of the IMF, 0.4-1.3pp by the EC and the 0.4pp by the OECD. The forecasts for populistic governments were free of potential political biases or even too optimistic in some horizons. These models also confirm statistical artifacts related to the EDP procedure – international organizations produced too optimistic short-term forecasts for countries under corrective arm.

7. Conclusions

Our study does not confirm the hypothesis that international institutions tend to stigmatize ‘populist’ governments. However, we identify different and equally important problems associated with deficit forecasting.

First, all of the agencies threat leniently heavily indebted countries. Some indulgence is visible for economies under corrective arms of EDP in case of EC and OECD as well. The motives for such a forecasting approach can only be guessed. For example, the institutions may not be willing to trigger negative confidence shocks. The problem could also be a result of excessive trust in government predictions. Nonetheless, the results of underestimating the scale of government deficits have consequences. Although Spain has managed to reduce its sovereign debt in relation to its GDP, Italy, France, and Portugal are still heavily indebted.

In the case of the EC, another problem relates to forecasting deficits in emerging economies. We found cyclical biases in the EC forecasts, which could be a result of insufficient resources being dedicated to forecasting. Other problems may be related to a lack of analysis of documents in a country’s language or to acquiring information from a limited number of media outlets providing news coverage only in English.

Finally, our research confirmed the existence of problems described in the academic literature, specifically, the selective positive bias for some countries (e.g. Portugal, Spain) and strong autocorrelations of forecast errors. Both problems undermine the credibility of international institution forecasting methods.

Acknowledgements

The paper was prepared within the framework of research project No. 2018/29/N/HS4/00334. Analysis of international financial institutions fiscal forecasts consistency for European Union economies, financed by the National Science Center, Poland.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jakub Rybacki

Jakub Rybacki is a PhD student at the SGH Warsaw School of Economics, Economic Advisor at the Polish Economic Institute.

Notes

1 The theorem assumes a common and positive relationship between fiscal and current account deficits in the long term; e.g. an increase of government expenditures financed by debt increase should widen the external imbalance.

References

- Artis, M., & Marcellino, M. (2001). Fiscal forecasting: The track record of the IMF, OECD and EC. The Econometrics Journal, 4(1), 20–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/1368-423x.00051

- Batchelor, R. (2001). How useful are the forecasts of intergovernmental agencies? The IMF and OECD versus the consensus. Applied Economics, 33(2), 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036840121785

- BBC. (2019). Europe and nationalism: A country-by-country guide https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-36130006, accessed: 08/05/2019.

- Beetsma, R., Bluhm, B., Giuliodori, M., & Wierts, P. (2013). From budgetary forecasts to ex post fiscal data: Exploring the evolution of fiscal forecast errors in the European Union. Contemporary Economic Policy, 31(4), 795–813. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-7287.2012.00337.x

- Beetsma, R., Debrun, X., Fang, X., Kim, Y., Lledó, V., Mbaye, S., & Zhang, X. (2019). Independent fiscal councils: Recent trends and performance. European Journal of Political Economy, 57, 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2018.07.004

- Belke, A. (2017). The fiscal compact and the excessive deficit procedure: Relics of bygone times? The Euro and the Crisis. Financial and Monetary Policy Studies, 43, 131–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-45710-9_10

- Brück, T., & Stephan, A. (2006). Do Eurozone countries cheat with their budget deficit forecasts? Kyklos, 59(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6435.2006.00317.x

- Corsetti, G., & Müller, G. J. (2006). Twin deficits: Squaring theory, evidence and common sense. Economic Policy, 21(48), 598–638. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0327.2006.00167.x

- De Jong, J. F. M., & Gilbert, N. D. (2020). Fiscal discipline in EMU? Testing the effectiveness of the excessive deficit procedure. European Journal of Political Economy, 61, 101822. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2019.101822

- Doray-Demers, P., & Foucault, M. (2017). The politics of fiscal rules within the European Union: A dynamic analysis of fiscal rules stringency. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(6), 852–870. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1296883

- European Fiscal Board – EFB. (2020). 2020 annual report of the European Fiscal Board, https://ec.europa.eu/info/files/2020-annual-report-european-fiscal-board_en, accessed: 13/12/2020.

- Frankel, J., & Schreger, J. (2013). Over-optimistic official forecasts and fiscal rules in the eurozone. Review of World Economics, 149(2), 247–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-013-0150-9

- Gidron, N., & Hall, P. A. (2017). The politics of social status: Economic and cultural roots of the populist right. British Journal of Sociology, 68(S1), S57–S84. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12319

- Guardian. (2018). How populism emerged as an electoral force in Europe, https://www.theguardian.com/world/ng-interactive/2018/nov/20/how-populism-emerged-as-electoral-force-in-europe, accessed: 08/05/2019.

- Jonung, L., & Larch, M. (2006). Improving fiscal policy in the EU: The case for independent forecasts. Economic Policy, 21(47), 492–534. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0327.2006.00162.x

- Leal, T., Pérez, J. J., Tujula, M., & Vidal, J. P. (2008). Fiscal forecasting: Lessons from the literature and challenges. Fiscal Studies, 29(3), 347–386. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5890.2008.00078.x

- Merola, R., & Pérez, J. J. (2013). Fiscal forecast errors: Governments versus independent agencies? European Journal of Political Economy, 32, 285–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2013.09.002

- Piersanti, G. (2000). Current account dynamics and expected future budget deficits: Some international evidence. Journal of International Money and Finance, 19(2), 255–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5606(00)00004-8

- Pina, A. M., & Venes, N. M. (2011). The political economy of EDP fiscal forecasts: An empirical assessment. European Journal of Political Economy, 27(3), 534–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2011.01.005

- Poniatowski, G., Bonch-Osmolovskiy, M., Duran-Cabré, J. M., Esteller-More, A., & Śmietanka, A. (2018). Study and reports on the VAT Gap in the EU-28 member states: 2018 Final report. SSRN Electronic Journal, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3272816

- Pons, J. (2000). The accuracy of IMF and OECD forecasts for G7 countries. Journal of Forecasting, 19(1), 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-131X(200001)19:1<53::AID-FOR736>3.0.CO;2-J

- Reuter, W. H. (2015). National numerical fiscal rules: Not complied with, but still effective? European Journal of Political Economy, 39, 67–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2015.04.002

- Reuters. (2018). European Commission must treat Italy and France in same way – Salvini. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-italy-budget-salvini-france/european-commission-must-treat-italy-and-france-in-same-way-salvini-idUSKBN1OB1BG, accessed: 27/03/2019.

- Schuknecht, L., Moutot, P., Rother, P., & Stark, J. (2011). The stability and growth pact: Crisis and reform. CESifo DICE Report.

- Wyplosz, C. (2012). Fiscal rules: Theoretical issues and historical experiences. NBER Working Paper 17884, 1-28. https://doi.org/10.3386/w17884