Abstract

This study explored the mediating role of perceived organisational support and social support in the relationship between self-efficacy and career satisfaction among professional women. The participants comprised a non-probability sample of 606 professional women (white = 62%; black women of colour = 38%; mean age = 35.41 years, SD = 8.39 years) in early adulthood and established career stage, employed in the financial, engineering and human resources fields. Professional women completed standardised measures of perceived organisational support, social support, self-efficacy, and career satisfaction. Mediation analysis results showed that perceived organisational support and social support improved the relationship between women’s self-efficacy and their career satisfaction. Support resources from the workplace peers, family, and significant others may promote the interaction between self-efficacy and the career satisfaction of professional women. Findings imply that there is a need for organisations to provide supportive initiatives to promote self-efficacious beliefs and career satisfaction among professional women.

Introduction

Women face difficult societal hurdles including family career expectations, marriage, and family responsibilities which restrain the possibilities to progress in pursuit of their careers (Khalid et al., Citation2017). Research on women’s career aspiration and advancement are extensive, with emphasis on the barriers they encounter towards their professional development (Koekemoer et al., Citation2023). However, less consideration has been given to the interlinking role of the personal resources and the supportive resources which may enhance the women’s career advancement and satisfaction. It is noteworthy to state that work-based support was identified as imperative among aspirant professional women who seek to balance unique career goals and multiple life roles for their career advancement and success (Meglich et al., Citation2016; Takawira, Citation2018). Scholars acknowledge that multiple factors shape women’s career experiences, and optimal person–environment interaction may help women to develop their careers (Cook et al., Citation2005; Koekemoer, et al., Citation2023). However, femininity values that encourage relational self, emotional engagement, work–life balance, participation, and collaboration are not promoted (Loyola, Citation2016; Takawira, Citation2018). It is a considered view that women may excel in their careers within a contemporary protean setting (Crowley-Henry & Weir, Citation2007) and efficacy enhancing environment, including support from their social network (Karatepe & Olugbade, Citation2017; Takawira, Citation2020). Still, the accessibility of these support resources cannot be assumed and, if present, it is not clear how these work-related supportive mechanisms would improve the interaction between women’s self-efficacy and career satisfaction perceptions (Takawira, Citation2020). Relatively little attention has been directed at examining the extent to which perceived organisational support (POS) and social support mediate the relationship between self-efficacy and career satisfaction among professional women. This study aimed to fill this gap.

Women and careers: An ecological perspective

Women value mutual support and relatedness with others, often sacrificing their career needs by evaluating the potential impact of their career decisions on the needs of significant others (Cabrera, Citation2009; Starman & Vodopivec, 2020). To comprehend the dynamics of women’s career behaviour (Patton, Citation2013), the ecological perspective (see Bronfenbrenner, Citation1977) acknowledges multiple influences shaping women’s career experiences with emphasis on the relational aspect between systems (Starman & Vodopivec, 2020). Essentially, the ecological perspective suggests that human behaviour is a result of the continuing dynamic interaction between a person and the environment (Cook et al., Citation2002). For instance, from early childhood, women’s efficacy perceptions about themselves and their possibilities are shaped by enduring interactions with others within their immediate environment (Cook et al., Citation2005; Takawira, Citation2018). The interlinking role of the individual and the environment is important in conceptualising the career advancement of women considering the challenges or barriers that influence women’s career aspirations (Cook et al., Citation2002). Hence, the centrality of social networks and perceived support from multiple relationships determines how women develop efficacy beliefs which may shape their career advancement and satisfaction (Starman & Vodopivec, 2020; Takawira, Citation2018). Flores and colleagues (Citation2002) identified the potential internal barriers such as self-efficacy contributing to achieving positive outcomes with adolescent girls. Zeldin and colleagues (Citation2008) suggested that women depend on relational experiences to create and reinforce the confidence that they can succeed in male-dominated fields. Most relevantly, variables that influence self-efficacy skills and career satisfaction among professional women are not clearly understood, despite the potential value the evidence would add to work-place practices for professional women.

Support resources as mediators of self-efficacy and career satisfaction relationship

The availability and development of support resources are important mechanisms for a positive work experience (Kerksieck et al., 2019). Support resources emanate from the structure and content of an individual’s social relationships and their effect flow from the information, influence, and solidarity they make available to the individual (Hirschi, Citation2012). It is a considered view that perceived organisational support (POS) and social support generate support structures and processes which enable individuals to engage in various career paths and prospects for career advancement (Takawira, Citation2020; Yu, Citation2010). POS is defined as the employees’ beliefs about the extent to which the organisation values their contribution and cares about their well-being (Eisenberger et al., Citation2004). The organisational support theory posits that POS depends on employees’ attributions concerning the organisation and should be enhanced to the extent that employees attribute favourable treatment from the organisation (Kurtessis et al., Citation2017; Takawira, Citation2018). Khurshid and Anjum (Citation2012) found that female teachers experienced lower POS than male teachers.

Further, Scanlan and colleagues (Citation2018) observed that the lack of appreciation of women’s personal needs led to disengagement and reduced commitment towards working in the organisation. These findings suggest that without organisational supportive mechanisms, it is unlikely that women can successfully manage their careers and confidently advance the challenges and demands of their work and non-work life (Karatepe & Olugbade, Citation2017) to achieve career advancement and satisfaction (Takawira, Citation2020).

Taylor and Broffman (Citation2011) suggested that social support is a perception of being loved, cared for, and valued as part of a social network of reciprocated assistance and obligations. Sjolander and Ahlstrom (Citation2012) posited that social support networks represent reciprocal exchanges of verbal and non-verbal information. POS enhances emotional and instrumental support essential for career growth and attainment of career goals (Jairam & Kahl, Citation2012; Karatepe & Olugbade, Citation2017). For instances, Jepson (Citation2010) showed that women with higher levels of social support tend to experience more success in their careers as opposed to women with lower levels of social support. Likewise, Karatepe and Olugbade (Citation2017) observed that social work support boosted career satisfaction. Oti (Citation2013) found that parental influence and spousal support related to career growth, while collegial support predicted leadership positions. Conversely, individuals who are socially excluded from these relationships may feel unsupported because they lack the close relationships that can afford access to social support in the workplace (Sloan et al., 2013). Accordingly, Takawira (Citation2020) revealed that POS and social support have a mediating effect on career adaptability and career satisfaction. Likewise, Yalalova and Zhang (Citation2017) argued that work effort exerted a mediating effect on the relationship between self-efficacy and career satisfaction. However, limited studies could be traced on the mediating effect of POS and social support on the self-efficacy and career satisfaction of women in a developing economy.

Self-efficacy and career satisfaction

Self-efficacy is an important personal and motivational construct, which influences individual choices, goals, emotional reactions, effort, and persistence (Gist & Mitchell, Citation1992; Takawira, Citation2018). Self-efficacy is derived from the social cognitive theory (SCT) (see Bandura, Citation2004) and is defined as the beliefs about one’s capacity to engage in a specific task and be able to complete it (Michaelides, Citation2008). Efficacy beliefs are dependent on cognitive processing from various sources of efficacy information (i.e., past performance, vicarious experience, social persuasion, and physiological arousal) and once formed, contribute significantly to the level and quality of human functioning (Bandura, Citation2012). Past performance is the most influential source of self-efficacy since it is based on personal mastery of experiences (Bandura, Citation2012). For women, social persuasions and vicarious experiences were found to be the primary sources of self-efficacy, whereas for men, efficacy beliefs were created primarily because of the interpretations they make of their ongoing achievements and successes (Zeldin et al., Citation2008). Research suggests that self-efficacy is positively related to career satisfaction, i.e., individuals with higher self-efficacy also reported higher subjective career success than individuals with lower self-efficacy (Karatepe & Olugbade, Citation2017; Takawira, Citation2018). Career satisfaction is defined as an employee’s subjective perceptions regarding career progression and/or success consistent with the goals in one’s career (Spurk, & Abele, 2014; Takawira Citation2020). In line with this view, women’s subjective career success (i.e., career satisfaction) may relate to their evaluation with reference to self-defined stages (i.e., career stages), aspirations, and opinions of significant others (Mahidi, Citation2015; Takawira, Citation2018). Salisu and colleagues (Citation2020) argued that personal resources relate to subjective career success (i.e., career satisfaction). Likewise, Koekemoer and colleagues (Citation2023) found personal resources to be significant predictors of subjective career success. Therefore, women’s self-efficacy beliefs could enable them to define career goals or aspirations and determine how environmental enablers are viewed and obstacles are managed to achieve career satisfaction. Research studies found that employees with higher self-efficacy were likely to work hard at task performance, since they were confident that their efforts would yield career success and satisfaction (Khalid et al., Citation2017; Takawira, Citation2018). Specifically, Khalid and colleagues (Citation2017) found that self-efficacy positively influenced career satisfaction. By contrast, Kim and colleagues (2008) reported that self-efficacy perceptions related negatively to overall pay satisfaction. Both studies did not explicitly focus on professional women. The present study examines the relationship between self-efficacy and career satisfaction as well as the mediating role of support resources.

The goal of the study

The objective of the current study was to examine the extent to which POS and social support mediated the relationship between self-efficacy and career satisfaction among professional women. The current study aimed to address the question: “How do POS and social support mediate the relationship between self-efficacy and career satisfaction of women professionals in a developing economy?” We proposed to test the following hypothesis: “Perceived organisational and social support statistically and significantly mediate the relationship between self-efficacy and career satisfaction among professional women.”

Method

Participants and setting

A non-probability purposive sample comprised 606 South African professional women affiliated with the financial, engineering, and human resources professional bodies (62% = white women; 38% = black African, coloured, and Indian women). Most participants (85%) were in the early adulthood and establishment career stage (aged 25−44 years). Most participants (73.8%) had obtained a postgraduate qualification, as expected in the accounting and engineering professions, since employees are expected to have these qualifications at entry level (see Takawira, Citation2018). Overall, the sample participants were married and occupied managerial-level positions in their organisations.

Measures

Perceived organisational support (POS)

The Scale Perceived Organisational Support (SPOS: Eisenberger et al, 1986) was utilised to assess perceived organisational support. This scale consisted of 36-item (example item: “The organisation strongly considers my goals and values”). Items are scored as per the seven-point Likert-type response format ranging from 0 = strongly disagree, to 7 = strongly agree. High scores suggest participants perceived their organisation to be supportive of their career goals and work activities. In the current study, scores on the SPOS scale achieved a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.96 (see Takawira, Citation2018).

Social support

Social support was measured with the 12-item Multi-dimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS: Zimet et al., Citation1988). The scale measures three subscales: family (4 items, e.g., “I get the emotional help and support l need from my family”); friends (4 items, e.g., “I have friends with whom l can share my joys and sorrows”); and significant others (4 items, e.g., “There is a special person who is around when l am in need”).

Items were scored as per the seven-point Likert-type response format ranging from 1 = very strongly disagree, to 7 = very strongly agree. High scores indicate high levels of perception of social support. In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha values for scores on the MSPSS ranged between 0.93 and 0.97 (see Takawira, Citation2018).

Self-efficacy

The New General Self-Efficacy (NGSE: Chen et al., Citation2001) scale was used to measure self-efficacy. This scale consisted of 8-item (example item: “I will be able to achieve most of the goals that l set for myself”). Items are scored on a five-point Likert-type response format ranging from 1 = strongly disagree, to 5 = strongly agree. High scores suggest participants’ career confidence to pursue ambitions and realise career goals. In the current study, scores from the NGSE scale achieved a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93 (see Takawira Citation2018).

Career satisfaction

The Career Satisfaction Scale (CSS: Greenhaus et al., Citation1990) was used to measure career satisfaction. This scale consisted of five items (example item: “I am satisfied with the progress l have made towards meeting my overall career goals”). Items are scored according to a five-point Likert-type response format ranging from 1 = strongly disagree, to 5 = strongly agree). High scores on this measure indicate high levels of career satisfaction. In the current study, scores on the CSS scale attained a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.92 (see Takawira, Citation2018).

Statistical analysis

The main data analysis approach utilised was multiple mediation by means of the simple mediation technique and bootstrapping (bias corrected [BC]) by Preacher and Hayes (Citation2008). The mediation effect tests assessed the support resources (POS and social support) on the self-efficacy and career satisfaction relationship. Rucker and colleagues (Citation2011) provide four requirements that should be met to establish the significance of mediating effects. First, the independent variable (self-efficacy) is a significant predictor of the dependent variable (i.e., career satisfaction). Second, the independent variable (self-efficacy) is a significant predictor of the mediators (i.e., POS and social support). Third, the mediators (i.e., POS and social support) are significant predictors of the dependent variable (career satisfaction). Finally, the independent variable (self-efficacy) is significantly reduced (partial mediation) after statistically controlling for the mediators (POS and social support). In addition, the more reliable and stringent bootstrapping bias corrected 95% lower and upper confidence intervals (CIs) excludes zero to support the significant indirect effect of the relevant mediator variables (Preacher & Hayes, Citation2008; Rucker et al., Citation2011).

Procedure and ethical considerations

The Research and Ethics Committee of the Department of Industrial and Organisational Psychology at the University of South Africa (Unisa) gave their approval for the study to be conducted (#2015/CEMS/IOP/004). Furthermore, permission to conduct the research study was obtained from the management of the professional bodies involved. Following a brief explanation of the goal of the study, consent, and its confidential nature, participants provided informed consent and completed a self-administered online survey at their convenience.

Results

Descriptive and correlation statistics

The results (means, standard deviations, and internal consistency reliabilities and correlations) for all the scale constructs are presented in . Self-efficacy correlated significantly and positively with social resources (POS and social support) and career satisfaction (r ≥ 0.09 ≤ r ≤ 0.51; small to large practical effect; p ≤ 0.05).

Table 1: Means, standard deviations, reliabilities and correlations among constructs

Mediation effect of POS and social support in the relationship between self-efficacy and career satisfaction

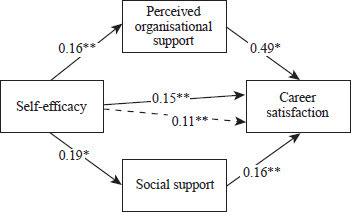

Results (see and ) showed that the mediation role of POS and social support in the relationship between self-efficacy and career satisfaction was significant. Evidently, the four conditions proposed by Rucker and colleagues (Citation2011) for significant mediation effects were achieved.

Table 2: Direct and indirect effects of self-efficacy (NGSE) on career satisfaction (CSS) through scale perceived organisational support (SPOS) and social support (MSPSS)

and show that self-efficacy had a significant direct effect on career satisfaction once the POS and social support constructs were applied as mediation variables (0.15; p ≤ 0.01; lower CI 0.08; upper CI 0.22). Self-efficacy had a significant direct pathway to POS and social support (≥ 0.16 ≤ 0.19; p ≤ 0.05 − positive pathway; lower CI 0.07; 0.09 upper CI 0.26; 0.28). POS had a significant direct pathway to career satisfaction (0.49; p ≤ 0.05 − positive pathway; lower CI 0.42; upper CI 0.55). Social support had a significant direct pathway to career satisfaction (0.16; p ≤ 0.01 − positive pathway; lower CI 0.09; upper CI 0.25). Self-efficacy had a significant indirect effect on career satisfaction as mediated through POS and social support (0.11; p ≤ 0.01; lower CI 0.06; upper CI 0.17). The BC bootstrapping 95% lower and upper CI did not include zero (Korpela & Kinnunen, Citation2010; Preacher & Hayes, Citation2008). This indicated the significant indirect (partial mediation) role of POS and social support on the self-efficacy and career satisfaction relationship.

Overall, the results stated in indicated that through the mediation analysis, perceived organisational and social support were observed to strengthen relations between self-efficacy and career satisfaction. Consequently, when self-efficacy was significantly enhanced, career satisfaction was further improved through the intervention of POS and social support. Thus, the hypothesis that perceived organisational and social support would mediate the relationship between self-efficacy and career satisfaction among professional women was supported by these findings.

Discussion

Multiple mediation analysis confirmed the hypothesis of this study in demonstrating that support resources (i.e., POS and social support) mediated the relationship between self-efficacy and career satisfaction. POS and social support were seen to strengthen the influence of self-efficacy beliefs on career satisfaction. As such, perceptions of self-efficacious beliefs were increased in the presence of POS and social support which ultimately enhanced the career satisfaction experiences of professional women. The findings could be ascribed to the current or cumulative support resources and self-efficacious beliefs of women which enhanced their career satisfaction (Takawira, Citation2018). Based on the conservation of resources theory (Ming-Chu, & Meng-Hsiu, 2015), it can be argued that the presence of adequate resources in the form of POS and social support and the cumulative effect of self-efficacious beliefs, career satisfaction is enhanced among professional women (Takawira, Citation2018). Consistent with this view, a study by Nikhil and Arthi (Citation2018) argued that POS has a significant positive influence on the self-efficacy levels of employees, to the extent that employees who perceived a supportive work environment were intrinsically motivated and self-efficacious.

Social exchange theory (SET) by Cropanzano and Mitchell (Citation2005) suggests that reciprocation of increasingly valued resources should strengthen the exchange relationship. POS, social support, and self-efficacy appeared to be reciprocally related to increasing career satisfaction among professional women (Taylor & Broffman, Citation2011). In that view, a sense of confidence about career aspirations and capabilities, as perceived by the individual and supportive information (i.e., social persuasion and vicarious experiences), should therefore generate positive career success outcomes as measured by career satisfaction (Bandura, Citation2012; Takawira, Citation2018). Liu (Citation2018) suggested the buffering effect of social support on job satisfaction. Kirkbesoglu and Ozder (Citation2015) also found that POS boosted career satisfaction in terms of advancement and achievement of career goals. Similarly, Gayathri and Karthikeyan (Citation2016) concur that social support and self-efficacy boosted life satisfaction. Conversely, Maan and colleagues (Citation2020), revealed that the relationship between POS and job satisfaction was weaker when employees’ proactive personality was higher rather than lower.

The current findings suggest that professional women with higher levels of self-efficacy beliefs (i.e., belief in one’s capabilities in task performance) to help the organisation achieve its goals and objectives, are likely to be perceived favourably or valued and expect that increased performance will translate to intrinsic rewards, in this case, career satisfaction (Kurtessis et al., Citation2017). In addition, professional women who participated in the study were confident that they could count on their family and friends to provide quality assistance, such as listening, affection, offering advice, or any other way to help them achieve their career advancement (Takawira, Citation2018), which would likely partially increase experiences of career satisfaction. Spurk and Abele (Citation2014) observed that people perform at levels commensurate with their self-efficacy beliefs. Accordingly, Liu (Citation2018) showed that self-efficacy is an important factor in job satisfaction. Likewise, Mahidi (Citation2015) noticed that self-efficacy played an important role towards women’s perceptions of career satisfaction. Ahmed and Carrim (Citation2016) observed that the emotional support received from husbands assisted the career progression of women. The findings suggest that it is important to instil and strengthen women’s efficacy beliefs in their work participation and design interventions aimed at promoting confidence about their capabilities to perform successfully and accomplish career goals they set for themselves (Bandura, Citation2012; Takawira, Citation2018). These findings highlight the importance of social resources and self-efficacy in enhancing career satisfaction among professional women.

Theoretical and practical implications

The current findings support the need for organisations to develop supportive resources to improve women’s self-efficacy and career satisfaction. The career development of women occurs within a context of ecological micro and macro perspectives in which a combination of specific work and family characteristics affect the quality of women’s work performance and career outcomes (Cook et al., Citation2005; Takawira, Citation2018). Given the increasing participation of women in fields such as accounting and engineering in the African developing economy, a lack of support resources from significant others and organisations is still apparent (Mahidi, Citation2015; Takawira, Citation2018). For instance, a lack of encouragement from the significant others and organisational barriers were observed to seriously corrode the actual women’s efficacy beliefs which affected their career satisfaction (Khalid et al., Citation2017; Mahidi, Citation2015). POS and social support can enhance professional women’s self-efficacy beliefs, which should give them confidence to adopt career development initiatives that best suit their career needs (Takawira, Citation2020). For instance, supportive work environments, coaching, and mentoring practices to raise self-efficacy beliefs can result in higher career satisfaction (Khalid et al., Citation2017). Career counsellors could encourage and strengthen the efficacy beliefs of women by applying the four principal sources of self-efficacy beliefs; namely past performance or mastery experiences, social modelling, verbal persuasion, and emotional arousal (Bandura, Citation2012; Takawira, Citation2018).

Since career satisfaction takes an individual approach, women should be encouraged through social persuasion toward meeting their own career goals and advancement. Likewise, career counsellors could use verbal persuasion by encouraging women to endure when confronted with obstacles as well as express confidence in their capabilities to achieve career goals (Bandura, Citation2012; Takawira, Citation2018). These types of practices not only influence their self-efficacy beliefs but also enhances their career satisfaction (Khalid et al., Citation2017). Additionally, professional support and guidance, and supportive network platforms would enhance women’s career development goals for their career progression and guide their efforts in improving performance on work-related tasks to achieve career satisfaction (Takawira, Citation2020). These career development initiatives from organisations and supportive social networks to address women’s unique needs, are critical for their sustainable organisational performance, favourable work experience, career advancement, and satisfaction.

Limitations and future directions

Though the findings provided strong support to the theoretical underpinnings of the study, like all research, it was not without limitations. The study utilised a cross-sectional design and data collected at a single point in time to investigate the relationship dynamics between the professional women’s social resources, self-efficacy, and career satisfaction. This design makes it difficult to ascertain the causal direction of relationships or change processes in the interaction of social resources, self-efficacy, and career satisfaction as would a longitudinal study in examining these dynamic relationships in the long-term careers of women. Moreover, the study predominated white women in the financial, engineering, and human resources industry, which limits the generalisability of the findings to other populations or ethnic groups. Future research could consider more diverse groups to assess women’s support resources, self-efficacy, and career satisfaction perceptions. Besides, it is important to consider potential confounding variables and differences among diverse populations. Given that the study was dominated by the white female participants, it is important to concede that there could be variations in the results when applied to other ethnic contexts. Finally, it was hypothesised that POS and social support would mediate the relationship between self-efficacy and career satisfaction. There is also a possibility for future research to test the moderating role of POS and social support among women. Despite these limitations, the findings provide evidence that supportive initiatives positively promote the self-efficacious beliefs and ultimately the career satisfaction of professional women.

Conclusion

The value of the findings in the present study demonstrates the significance of support initiatives in advancing the relationship between self-efficacy and career satisfaction among women. Overall, this research showed that through mediation analysis, self-efficacy related significantly to career satisfaction through POS and social support. These findings provided evidence of POS and social support as important initiatives designed to enhance the relationship between self-efficacy and the career satisfaction of professional women. Therefore, developmental initiatives to address women’s unique needs through transformative supportive workplace practices and social networks should be utilised to increase the career satisfaction of aspirant professional women.

Compliance with ethical standards

The author declares that all procedures performed in conducting this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and the 1964 Helsinki declaration as amended. The author obtained informed consent from all individual participants.

Competing interests

The author declares that she has no conflict of interests.

Data availability

Data generated for this study are available when need.

References

- Ahmed, S., & Carrim, N. (2016). Indian husbands’ support of their wives’ upward mobility in corporate South Africa: Wives’ perspectives. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 42(1): a1354. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v42i1.1354

- Bandura, A. (2004). Swimming against the mainstream: The early years from chilly tributary to transformative mainstream. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 42, 613–630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2004.02.001

- Bandura, A. (2012). On the functional properties of self-efficacy revisited. Journal of Management, 38(1), 9–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311410606

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. The American Psychologist, 32, 513–531. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513

- Cabrera, E. F. (2009). Protean organizations: Reshaping work and careers to retain female talent. Career Development International, 14(2), 186–201. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430910950773

- Chen, G., Gully, S. M., & Eden, D. (2001). Validation of a new general self-efficacy scale. Organizational Research Methods, 4, 62–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442810141004

- Cook, E. P., Heppner, M. J., & O’Brien, K. M. (2002). Career development of women of color and white women: Assumptions, conceptualization, and interventions from an ecological perspective. The Career Development Quarterly, 50, 291–305. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2002.tb00574.x

- Cook, E. P., Heppner, M. J., & O’Brien, K. M. (2005). Multicultural and gender influences in women’s career development: An ecological perspective. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 33, 165–179. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1912.2005.tb00014.x

- Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31, 874–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305279602

- Crowley-Henry, M., & Weir, D. (2007). The international protean career: Four women’s narratives. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 20(2), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534810710724784

- Eisenberger, R., Jones, J. R., Aselage, J., & Sucharski, I. L. (2004). Perceived organizational support. In J. A.-M. Coyle-Shapiro, L. M. Shore, M. S. Taylor, & L. E. Tetrick (Eds.), The employment relationship: Psychological and contextual perspectives (pp. 206–225). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199269136.003.0010

- Flores, L. Y., Byars, A., & Torres, D. M. (2002). Expanding career options and optimizing abilities: The case of Laura. The Career Development Quarterly, 50, 311–316. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2002.tb00576.x

- Gayathri, N., & Karthikeyan, P. (2016). The role of self-efficacy and social support in improving life satisfaction: The mediating role of work–family enrichment. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 224(1), 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000235

- Gist, M. E., & Mitchell, T. R. (1992). Self-efficacy: A theoretical analysis of its determinants and malleability. Academy of Management Review, 17(2), 183–211. https://doi.org/10.2307/258770

- Greenhaus, J. H., Parasuraman, S., & Wormley, W. M. (1990). Effects of race on organizational experiences, job performance evaluations, and career outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 33, 64–86. https://doi.org/10.2307/256352

- Hirschi, A. (2012). The career resources model: An integrative framework for career counsellors. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 40(4), 369–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2012.700506

- Jairam, D., & Kahl, D. H. (2012). Navigating the doctoral experience: The role of social support in successful degree completion. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 7, 311–329. https://doi.org/10.28945/1700

- Jepson, L. (2010). An analysis of factors that influence the success of women engineering leaders in corporate America [Doctoral dissertation]. Antioch University. https://etd.ohiolink.edu/pg_6?0:NO:6:P6_KEYWORDS:20career20development

- Karatepe, O., & Olugbade, O. (2017). The effects of work social support and career adaptability on career satisfaction and turnover intentions. Journal of Management & Organization, 23(3), 337–355. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2016.12

- Khalid, K., Magbool, S., & Ayub, N. (2017). Women’s glass ceiling beliefs and career satisfaction in view of occupational self-efficacy: A tale of two countries. Ekonomska Istrazivanja, 36(3): 2188914. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2023.2188914

- Khurshid, F., & Anjum, A. (2012). Relationship between occupational stress and perceived organisational support among the higher secondary teachers. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 48, 9336–9343.

- Kirkbesoglu, E., & Ozder, E. H. (2015). The effect of organizational performance on the relationship between organizational support and career satisfaction: An application on insurance industry. Journal of Management Research, 7(3), 35–50. https://doi.org/10.5296/jmr.v7i3.7094

- Koekemoer, E., Olckers, C., & Schaap, P. (2023, March 28). The subjective career success of women: The role of personal resources. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1121989. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1121989

- Korpela, K., & Kinnunen, U. (2010). How is leisure time interacting with nature related to the need for recovery from work demands? Testing multiple mediators. Leisure Sciences, 33, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2011.533103

- Kurtessis, J. N., Eisenberger, R., Ford, M. T., Buffardi, L. C., Stewart, K. A., & Adis, C. S. (2017). Perceived organisational support: A meta-analytical evaluation of organizational support theory. Journal of Management, 43(6), 1854–1884. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315575554

- Liu, D. (2018). Mediating Effect of Social Support between the Emotional Intelligence and Job Satisfaction of Chinese Employees. Current Psychology (New Brunswick, N.J.), 37, 366–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-016-9520-5

- Loyola, M. C. C. A. (2016). Career development patterns and values of women school administrators. Journal of Education and Practice, 7(5), 26–31.

- Maan, A. T., Abid, G., & Butt, T. H. (2020). Perceived organizational support and job satisfaction: a moderated mediation model of proactive personality and psychological empowerment. Future Business Journal,6(1), 21-33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43093-020-00027-8

- Mahidi, A. S. (2015, 5–7 April). Self-efficacy towards career satisfaction among female engineers Paper presented at the International Conference on Human Resource Development. Johor Bahru Malaysia. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/83533094.pdf

- Meglich, P., Mihelič, K. K., & Zupan, N. (2016). The outcomes of perceived work-based support for mothers: A conceptual model. Journal of Contemporary Management Issues, 21(Special Issue), 21–50. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://hrcak.srce.hr/file/228549

- Michaelides, M. (2008). Emerging themes from early research on self-efficacy beliefs in school mathematics. Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 6(1), 219–234. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2009-07001-006

- Ming-Chu, Y., & Meng-Hsiu, L. (2015). Unlocking the black box: Exploring the link between perceive organizational support and resistance to change. Asia Pacific Management Review, 20(3), 177–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmrv.2014.10.003

- Nikhil, S., & Arthi, J. (2018). Role of perceived organizational support in augmenting self-efficacy of employees. Journal of Organization and Human Behaviour, 7(1), 20–26. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3174186

- Oti, A. O. (2013). Social predictors of female academics’ career growth and leadership position in south-west Nigerian universities. Sage Open, 3(4), 1−11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244013506439.

- Patton, W. (2013). Understanding women’s working lives. In W. Patton (Ed.). Conceptualising women’s working lives: moving the boundaries of discourse (Vol. 5, pp. 3–21). Sense. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6209-209-9_1

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assess and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

- Rucker, D. D., Preacher, K. J., Tormala, Z. L., & Petty, R. E. (2011). Mediation analysis in social psychology: Current practices and new recommendations. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(6), 359–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00355.x

- Salisu, I., Hashim, N., Mashi, M. S., & Aliyu, H. G. (2020). Perseverance of effort and consistency of interest for entrepreneurial career success. Journal of Entrepreneur in Emerging. Economies, 12, 279–304. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-02-2019-0025

- Scanlan, G. M., Cleland, J., Walker, K., & Johnston, P. (2018). Does perceived organisational support influence career intentions? The qualitative stories shared by UK early career doctors. BMJ Open, 8(3), e019911. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29921689/

- Sjolander, C., & Ahlstrom, G. (2012). The meaning and validation of social support networks for close family of persons with advanced cancer. BMC Nursing, 11(1): 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6955-11-17

- Spurk, D., & Abele, A. E. (2014). Synchronous and time-lagged effects between occupational self-efficacy and objective and subjective career success: Findings from a four-wave and 9-year longitudinal study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 84, 119–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2013.12.002

- Takawira, N. (2018). Constructing a psychosocial profile for enhancing the career success of South African professional women [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of South Africa.

- Takawira, N. (2020). Mediation effect of perceived organisational and social support in the relationship between career adaptability and career satisfaction among professional women. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 30(1), 23–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2020.1716550

- Taylor, S. E., & Broffman, J. I. (2011). Psychosocial resources: Functions, origins, and links to mental and physical health. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 44, 1–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-385522-0.00001-9

- Yalalova, J. F., & Zhang, L. (2017). The impact of self-efficacy on career satisfaction: Evidence from Russia. Sustainable Development of Science and Education, 2, 141–150. UDC 338.24

- Yu, C. (2010). Career success of knowledge workers: The effects of perceived organisational support and person-job fit. iBusiness, 2(4), 389–394. https://doi.org/10.4236/ib.2010.24051

- Zeldin, A. L., Britner, S. L., & Pajares, F. (2008). A comparative study of the self-efficacy beliefs of successful men and women in mathematics, science, and technology careers. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 45(9), 1036–1058. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20195

- Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52, 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2