Abstract

Objective: To examine patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in patients with different rheumatoid arthritis (RA) disease activity levels and identify residual symptoms.

Methods: Post hoc analyses of overall and Japanese data from two randomized controlled trials including RA patients with previous inadequate responses to methotrexate (NCT01710358) or no/minimal previous disease-modifying antirheumatic drug treatment (NCT01711359) (sponsor: Eli Lilly and Company). Week 24 assessments were disease activity (Simplified Disease Activity Index, Disease Activity Score/Disease Activity Score 28 joints-erythrocyte sedimentation rate) and PROs (pain visual analog scale [VAS], morning joint stiffness [MJS], Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue, and Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 Health Survey Physical and Mental Component Scores).

Results: Patients achieving remission/low disease activity (LDA) at Week 24 had larger/significant improvements from baseline in pain, MJS, disability, fatigue, and physical and emotional quality of life versus patients with high/moderate disease activity. Some patients achieving remission and LDA, reported residual pain (pain VAS >10 mm): 20.8–39.3% and 48.7–70.0% (overall study populations), 16.0–34.5% and 47.1–62.0% (Japanese patients). Residual MJS and fatigue were also reported.

Conclusion: Remission/LDA were associated with improvements in PROs in overall and Japanese patient populations; however, some patients achieving remission had residual symptoms, including pain.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic disease associated with inflammatory activity and joint damage with an estimated worldwide prevalence ranging from 0.33 to 1.1% [Citation1], and 1.0% in Japan [Citation2]. The manifestations of RA can include disability, pain, limitations in physical function, decreased quality of life (QOL), and other impairments important to patients [Citation3–6]. Recent studies in Japan have also demonstrated that RA can lead to work productivity loss [Citation7], and is associated with cardiovascular comorbidities [Citation8]. Current treatment recommendations for RA emphasize the importance of the treat-to-target approach [Citation9], where the aim is remission [or, in some instances, low disease activity (LDA)] assessed by a composite measure of disease activity, such as the Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI) Disease Activity Score/Disease Activity Score in 28 joints (DAS28), or Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) [Citation10,Citation11]. The treat-to-target approach recommends involving patients in decision making concerning treatment targets and strategies. To this end, although current treatments for RA can effectively inhibit inflammatory activity and progression of joint damage [Citation12], there is evidence that some patients have residual symptoms and impairments as indicated by various patient-reported outcomes (PROs) [Citation13,Citation14]. PROs are a particularly important means of assessing such symptoms and impairments as they can provide direct evidence about how RA and treatment of RA affects patient well-being and functioning [Citation15,Citation16].

Evidence that patients who achieve remission or LDA have residual symptoms comes from both randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies. For instance, in the ORAL Start multinational RCT of patients who were methotrexate (MTX)-naive, 15–22% who achieved remission (CDAI, SDAI) and 31–55% who achieved LDA (CDAI) at 6 months still experienced RA-related pain [visual analog scale (VAS)] [Citation17]. Norwegian and North American registry studies of patients have also provided evidence of residual symptoms. In Norway, ∼30% of patients starting new disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) therapy who achieved remission (DAS28) after 6 months reported high levels of fatigue (VAS) [Citation18]. In North America, 57–76% of patients starting biologic therapy who achieved lower disease activity [86% LDA or remission (CDAI)] after 12–15 months did not achieve the minimum clinically important difference (MCID) for various PROs {physical function [modified Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ): 76%], pain (VAS: 58%), fatigue (VAS: 57%), and patient’s assessment of disease activity [Patient’s Global Assessment of Disease Activity (PtGA)]: 57%} [Citation19]. In another (single clinic) observational study of patients with RA [Citation20], those achieving remission (SDAI) did not achieve ‘normal’ health-related QOL levels as indicated by HAQ, Short Form 36, Short Form 6D, Euro-QOL 5D, and Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire assessments. To date, however, there have been no reports on residual symptoms as indicated by PROs among patients achieving remission or LDA after previous inadequate responses to MTX, or in Japanese patients achieving remission or LDA. Further, there are relatively limited data available in general about PROs in Japanese patients with RA [Citation21]. Having a better understanding of residual symptoms and how disease activity relates to PROs in these patients, including those from different populations with different cultural norms that could affect responses, may help facilitate better treatment strategies.

RA-BEAM [Citation22] and RA-BEGIN [Citation23] were large-scale, multinational, phase 3 RCTs, which included patients with RA who had a previous inadequate response to MTX (RA-BEAM) or who had no or minimal previous DMARD treatment (RA-BEGIN). Both studies included patients from Japan. The objective of these post hoc analyses of data from RA-BEAM and RA-BEGIN was to examine PROs in patients who had differing levels of disease activity [high disease activity (HDA), moderate disease activity (MDA), LDA, or remission] at Week 24, thereby assessing the relationship between disease activity and PROs, and identifying any residual symptoms. Analyses were carried out for the overall and Japanese subgroup populations of both studies.

Material and methods

Study design

These post hoc analyses were from two 52-week, large, randomized, double-blind, placebo/active-controlled phase 3 trials of baricitinib for the treatment of RA; RA-BEAM (NCT01710358) and RA-BEGIN (NCT01711359). RA-BEAM included patients who had a previous inadequate response to MTX, whereas RA-BEGIN included patients who had no or minimal previous DMARD treatment. Details of the individual trials are described in the primary publications [Citation22–25]. Protocols for both trials were approved by the institutional review boards at all sites and carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice. All patients provided written informed consent before any study-related procedures occurred.

Outcomes assessment

The association between disease activities and PROs for the modified intention-to-treat (mITT) populations and the Japanese patients from RA-BEAM and RA-BEGIN were assessed. The mITT included all patients who had undergone randomization and were treated with at least one dose of the study drug. Disease activity was assessed using the SDAI and DAS28 based on the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28-ESR) at Week 24. Improvements in PROs from baseline to Week 24 and residual pain and other impairment at Week 24 for different disease activity categories were determined. Disease activity categories for SDAI were: SDAI >26 (HDA), 11 < SDAI ≤26 (MDA), 3.3 < SDAI ≤11 (LDA), and SDAI ≤3.3 (remission). Disease activity categories for DAS28-ESR were: DAS28-ESR >5.1 (HDA), 3.2 < DAS28-ESR ≤5.1 (MDA), 2.6 ≤ DAS28-ESR ≤3.2 (LDA), and DAS28-ESR <2.6 (remission).

PROs assessed at Week 24 were patient’s assessment of pain using a 0–100 mm VAS (pain VAS), duration of morning joint stiffness (MJS), HAQ-Disability Index (HAQ-DI), Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F), and Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 Health Survey version 2 Physical Component Score (SF-36 PCS) and Mental Component Score (SF-36 MCS).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline characteristics for the mITT population.

Patients in all treatment arms with observed SDAI or DAS28-ESR values at Week 24 were used to create the four mutually exclusive disease activity groups. Comparison of PROs between disease activity groups were made using analysis of covariance, adjusting for region (for overall populations only), joint erosion status at baseline, and the baseline score of the outcome measure. Missing PRO values were imputed using modified last observation carried forward. As the distribution of duration of MJS data was skewed, these data are presented as the median change and were compared among disease activity groups by Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test. Analyses were not adjusted for multiplicity.

The proportion of patients who met the following response criteria was determined to identify residual symptoms: pain VAS >10 mm [Citation26,Citation27], MJS >0 min, HAQ-DI MCID not achieved (change from baseline <0.22 [Citation28]), FACIT-F MCID not achieved (change from baseline <3.56 [Citation29]), and SF-36 PCS and SF-36 MCS MCIDs not achieved (change from baseline <5.0 and <2.5 [Citation30]). As there is no single, well-established cut-off value for pain VAS, a value of ≤10 mm was selected, based upon a literature review [Citation26,Citation27]. Likewise, there is no cut-off value for MJS. We selected a duration of 0 min as indicator of MJS remission, given the previously reported association between tenosynovitis and MJS in patients with RA [Citation31].

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS® version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Baseline characteristics

The overall population included 1305 patients in RA-BEAM and 584 patients in RA-BEGIN. The Japanese population included 249 patients in RA-BEAM and 104 patients in RA-BEGIN. Baseline demographics and clinical measures of disease activity were generally similar between the overall and Japanese populations and between studies (). Reflecting the different patient populations (a previous inadequate response to MTX in RA-BEAM versus no or minimal previous DMARD treatment in RA-BEGIN), the duration of RA was longer and mTSS scores were higher for patients in RA-BEAM than for patients in RA-BEGIN. Note: the baseline characteristics in are also disclosed in a related manuscript [Citation32] describing the results of a separate post hoc analysis of data from RA-BEAM and RA-BEGIN.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics for overall and Japanese patient populations in studies RA-BEAM and RA-BEGIN.

Changes from baseline in PROs

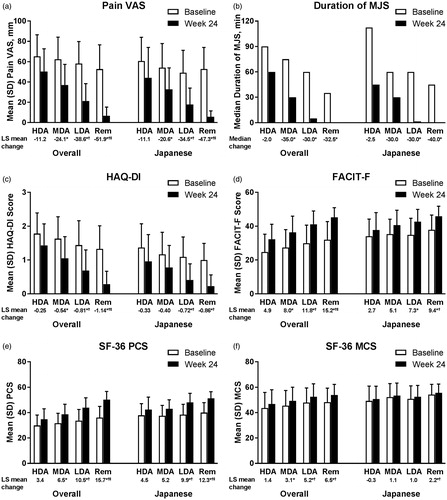

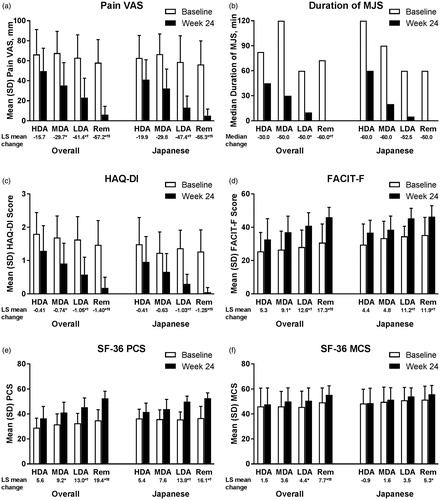

Patients achieving remission or LDA at Week 24 had less pain, disability, and fatigue, a shorter duration of MJS, and better physical and emotional QOL (SF-36 PCS and SF-36 MCS, respectively) at baseline, and larger improvements from baseline in PROs at Week 24 than patients with HDA or MDA at Week 24 ( and , Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). These findings were consistent, regardless of patient population, study, or disease activity measure.

Figure 1. Change from baseline in (a) Pain VAS, (b) duration of MJS, (c) HAQ-DI, (d) FACIT-F, (e) SF-36 PCS, and (f) SF-36 MCS by SDAI-defined disease activity at Week 24 for overall and Japanese populations of Study RA-BEAM. For Pain VAS, HAQ-DI, and duration of MJS, lower values/scores indicate better outcomes. For FACIT-F, SF-36 PCS, and SF-36 MCS, higher scores indicate better outcomes. HDA: SDAI >26; MDA: 11 < SDAI ≤26; LDA: 3.3 < SDAI ≤11; Rem: SDAI ≤3.3. *p<.05 versus HDA; †p<.05 versus MDA; ‡p<.05 versus LDA. FACIT-F: Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue; HAQ?DI: Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index; HDA: high disease activity; LDA: low disease activity; LS: least squares; MCS: Mental Component Score; MDA: moderate disease activity; MJS: morning joint stiffness; PCS: Physical Component Score; Rem: remission; SDAI: Simplified Disease Activity Index; SF-36: Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 Health Survey version 2; VAS: visual analog scale.

Figure 2. Change from baseline in (a) Pain VAS, (b) duration of MJS, (c) HAQ-DI, (d) FACIT-F, (e) SF-36 PCS, and (f) SF-36 MCS by SDAI-defined disease activity at Week 24 for overall and Japanese populations of Study RA-BEGIN. For Pain VAS, HAQ-DI, and duration of MJS, lower values/scores indicate better outcomes. For FACIT-F, SF-36 PCS, and SF-36 MCS, higher scores indicate better outcomes. HDA: SDAI >26; MDA: 11 < SDAI ≤26; LDA: 3.3 < SDAI ≤11; Rem: SDAI ≤3.3. *p<.05 versus HDA; †p<.05 versus MDA; ‡p<.05 versus LDA. FACIT-F: Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue; HAQ?DI: Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index; HDA: high disease activity; LDA: low disease activity; LS: least squares; MCS: Mental Component Score; MDA: moderate disease activity; MJS: morning joint stiffness; PCS: Physical Component Score; Rem: remission; SDAI: Simplified Disease Activity Index; SF-36: Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 Health Survey version 2; VAS: visual analog scale.

Baseline scores and the magnitude of change from baseline at Week 24 were generally similar between patient populations, studies, and disease activity measures ( and , Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). There were, however, several exceptions. Specifically, patients in the Japanese populations tended to report less disability and fatigue, and better emotional QOL (SF-36 MCS) at baseline, with smaller changes from baseline at Week 24 in these PROs than patients in the overall populations, particularly in RA-BEAM. Notably, the improvements from baseline in the duration of MJS and fatigue were numerically larger in DMARD-naive (RA-BEGIN) than MTX inadequate responder (RA-BEAM) treatment populations (particularly fatigue in the Japanese population).

Proportion of patients who did not achieve response criteria for PROs

Pain VAS

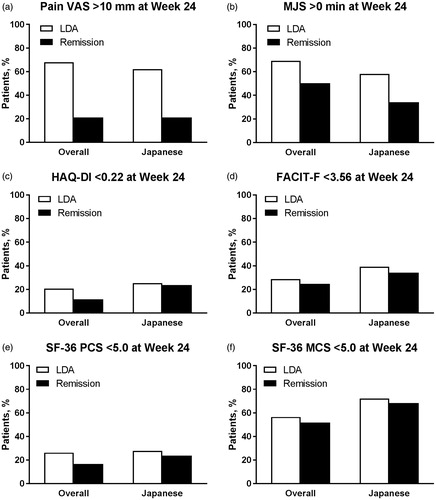

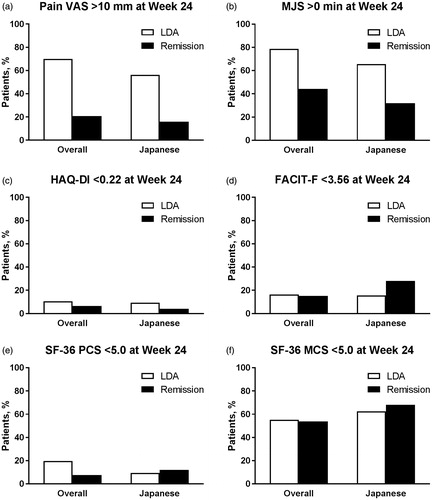

The proportion of patients who had Pain VAS >10 mm at Week 24 varied by disease activity measure, but was generally similar between the overall and Japanese populations, and between studies (, Supplementary Figures S1(a) and S2(a)). Among both populations and both studies, the proportion of patients achieving remission who had Pain VAS >10 mm ranged from 16.0 to 22.2% for SDAI and from 28.6 to 39.3% for DAS28-ESR. Corresponding ranges for LDA were 56.2–70.0% for SDAI and 47.1–53.1% for DAS28-ESR.

Figure 3. Proportion of patients (a) with Pain VAS >10 mm, with (b) MJS >0 min, who did not achieve the MCID for (c) HAQ-DI (change <0.22) or (d) FACIT-F (change <3.56), or who did not achieve the MCID for (e) SF-36 PCS (change <5.0) or (f) SF-36 MCS (change <5.0) at Week 24 by SDAI-defined disease activity (LDA and remission) at Week 24 for overall and Japanese populations of Study RA-BEAM. LDA: 3.3 < SDAI ≤11; Remission: SDAI ≤3.3; FACIT-F: Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue; HAQ?DI: Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index; LDA: low disease activity; MCS: Mental Component Score; MCID: minimum clinically important difference; MJS: Morning Joint Stiffness; PCS: Physical Component Score; SDAI: Simplified Disease Activity Index; SF-36: Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 Health Survey version 2; VAS: visual analog scale.

Figure 4. Proportion of patients (a) with Pain VAS >10 mm, with (b) MJS >0 min, who did not achieve the MCID for (c) HAQ-DI (change <0.22) or (d) FACIT-F (change <3.56), or who did not achieve the MCID for (e) SF-36 PCS (change <5.0) or (f) SF-36 MCS (change <5.0) at Week 24 by SDAI-defined disease activity (LDA and remission) at Week 24 for overall and Japanese populations of Study RA-BEGIN. LDA: 3.3 < SDAI ≤11; Remission: SDAI ≤3.3; FACIT-F: Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue; HAQ?DI: Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index; LDA: low disease activity; MCS: Mental Component Score; MCID: minimum clinically important difference; MJS: Morning Joint Stiffness; PCS: Physical Component Score; SDAI: Simplified Disease Activity Index; SF-36: Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 Health Survey version 2; VAS: visual analog scale.

MJS duration

The proportion of patients who had MJS >0 min at Week 24 was numerically higher for the overall populations than the Japanese populations, but was otherwise generally similar between studies, and between disease activity measures (, Supplementary Figures S1(b) and S2(b)). Among both studies and both disease activity measures, the proportion of patients achieving remission who had MJS >0 min ranged from 44.3 to 51.8% in the overall populations and from 32.0 to 40.0% in the Japanese populations. Corresponding ranges for LDA were 64.1 to 78.7% in the overall populations and 50.0 to 65.6% in the Japanese populations.

HAQ-DI (disability)

The proportion of patients who did not achieve the MCID for HAQ-DI (change <0.22) at Week 24 was numerically higher for patients in RA-BEAM than patients in RA-BEGIN, but was otherwise generally similar between the overall and Japanese populations, and between disease activity measures (, Supplementary Figures S1(c) and S2(c)). Among both populations and both disease activity measures, the proportion of patients achieving remission who did not achieve the MCID for HAQ-DI ranged from 11.7 to 27.3% in RA-BEAM and from 3.6 to 7.2% in RA-BEGIN. Corresponding ranges for LDA were 15.5–28.1% in RA-BEAM and 9.2–17.6% in RA-BEGIN.

FACIT-F (fatigue)

The proportion of patients who did not achieve the MCID for FACIT-F (change <3.56) at Week 24 was numerically higher for patients in RA-BEAM than patients in RA-BEGIN, but was otherwise generally similar between the overall and Japanese populations, and between disease activity measures (, Supplementary Figures S1(d) and S2(d)). Among both populations and both disease activity measures, the proportion of patients achieving remission who did not achieve the MCID for FACIT-F ranged from 24.8 to 40.0% in RA-BEAM and from 14.4 to 28.0% in RA-BEGIN. Corresponding ranges for LDA were 26.1–53.1% in RA-BEAM and 15.6–18.4% in RA-BEGIN.

SF-36 PCS and SF-36 MCS (QOL)

The proportion of patients who did not achieve the MCID for SF-36 PCS (<5.0) at Week 24 was numerically higher for patients in RA-BEAM than patients in RA-BEGIN, but was otherwise generally similar between the overall and Japanese populations, and between disease activity measures (, Supplementary Figures S1(e) and S2(e)). Among both populations and both disease activity measures, the proportion of patients achieving remission who did not achieve the MCID for SF-36 PCS ranged from 16.8 to 29.1% in RA-BEAM and from 7.1 to 12.0% in RA-BEGIN. Corresponding ranges for LDA were 20.4–37.5% in RA-BEAM and 9.4–19.8% in RA-BEGIN.

The proportion of patients who did not achieve the MCID for SF-36 MCS (<5.0) at Week 24 was numerically higher in the Japanese populations than the overall populations, but was otherwise generally similar between studies, and between disease activity measures (, Supplementary Figures S1(f) and S2(f)). Among both studies and both disease activity measures, the proportion of patients achieving remission who did not achieve the MCID for SF-36 MCS ranged from 51.8 to 58.6% in the overall populations and from 68.0 to 71.4% in the Japanese populations. Corresponding ranges for LDA were 52.1–59.2% in the overall populations and 62.5–81.2% for the Japanese populations.

For both SF-36 PCS and SF-36 MCS, results using the MCID cut-off of <2.5 were consistent with the MCID <5.0 results (data not shown).

Discussion

These are the first post hoc analyses of two large, multinational, RCTs to examine PROs by disease activity status in overall and Japanese RA populations who had previous inadequate response to MTX, or who had no or minimal previous DMARD treatment. We found that improvements in disease activity after 24 weeks were associated with improvements in PROs. However, despite achieving remission or LDA, our findings indicate that some patients may still have residual pain and other impairments. Having a better understanding of the relationship between disease activity control and PROs will help inform new or additional treatment strategies that focus on improving patients’ overall QOL as well as disease activity.

We found that patients achieving remission or LDA after 24 weeks reported less pain (Pain VAS), fatigue (FACIT-F), and disability (HAQ-DI), shorter MJS duration, and better physical and emotional QOL (SF-36 PCS and SF-36 MCS) than patients with HDA or MDA. However, not all patients achieved clinically meaningful improvements in the assessed PROs. Indeed, for patients who achieved remission, the following proportions did not achieve MCIDs: HAQ-DI: 4–27%; FACIT-F: 14–40%; SF-36 PCS: 7–29%; and SF-36 MCS: 52–71%. Further, 16–39% of patients had Pain VAS >10 mm. Like with pain, many patients (32–52%) also continued to experience MJS, despite achieving remission. This ongoing MJS may, at least in part, be a reflection of subclinical synovitis [Citation31]. The low level of improvement in SF-36 MCS is likely because, consistent with previous findings [Citation30,Citation33], SF-36 MCS scores were close to normal at baseline; hence, there was limited scope for improvement. Other studies have also found that patients achieving remission or LDA have residual symptoms as determined by PROs assessing pain, disability, fatigue, and global disease activity [Citation17–19]. Taken together, our findings and those from other studies indicate that, despite achieving remission (assessed by composite measures of disease activity), some patients with RA still have residual symptoms.

The findings of our post hoc analysis were generally consistent between the overall and Japanese patient populations, and between patients who had a previous inadequate response to MTX and those who had no or minimal previous DMARD treatment. This suggests that, regardless of region or treatment background, some patients with RA may have unmet needs, despite achieving remission/LDA. However, we did observe several differences, including a numerically higher proportion of patients achieving remission or LDA who had no or minimal previous DMARD treatment who achieved clinically meaningful improvement in HAQ-DI, FACIT-F, and SF-36 PCS than patients who had a previous inadequate response to MTX. Patients at an earlier stage in their disease are more likely to experience improvement in PROs with treatment than patients with established RA who may have experienced more joint damage, chronic pain, and other comorbid physical and mental impacts. In patients with established RA, a better treatment option may not only lower disease activity, but also help improve QOL. To this end, we found, in a separate analysis, that patients treated with baricitinib who achieved LDA had greater improvement from baseline and less residual symptoms, as indicated by PRO assessments of pain (VAS) and physical function (HAQ-DI), than patients treated with adalimumab or placebo who achieved LDA [Citation34].

Our analyses have several notable strengths, including that the data were obtained from large-scale RCTs that included different/distinct patient populations, and that multiple measures of disease activity and PROs were assessed. Further, the PRO instruments used in these studies are well known and accepted instruments for the measurement of RA-related symptoms. Nevertheless, some limitations must be acknowledged, including the post hoc nature of the analyses, and the fact that the data were obtained under controlled trial conditions and, therefore, may not fully reflect real-world clinical practice. Finally, we used response criteria based on a mixture of MCIDs, threshold values (pain VAS), and anchors (MJS) in this study, because MCIDs or true thresholds have not been established for all assessed PROs. However, we believe that criteria based on these values provide relevant information on residual symptoms among patients achieving remission or LDA.

These post hoc analyses of data from two RCTs demonstrated that remission and LDA were associated with improvements in PROs in overall and Japanese RA patient populations with previous inadequate responses to MTX or no or minimal previous DMARD treatment. Despite achieving remission, as defined by composite measures of disease activity, following the treat-to-target approach [Citation12], some patients may still have residual symptoms, including pain, fatigue, MJS, and impaired QOL. Physicians should, therefore, be aware of this possibility and, in consultation with patients, consider additional or alternative treatment strategies to help address any residual symptoms.

Conflicts of interest

N.I. has received consulting fees and/or research grants from AbbVie, Astellas, Ayumi, BMS, Chugai, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eisai, Eli Lilly Japan K.K., Hisamitsu, Janssen, Kaken, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Otsuka, Pfizer Japan, Taisho Toyama, and Takeda. M.D. has received consulting fees and/or research grants from AbbVie, BMS, Eli Lilly and Company, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB. Z.C. is employed by Eli Lilly. B.Z., M.I., M.S., C.G., A.Q., and I.S. are employed by and own shares in Eli Lilly. Y.T. has received consulting fees, speaker fees, honoraria, and/or research grants from AbbVie, Astellas, Bristol-Myers, Chugai, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Kyowa-Kirin, Mitsubishi Tanabe, MSD, Ono, Pfizer, Sanofi, Takeda, UCB, and YL Biologics.

Role of the sponsor

Eli Lilly and Company was involved in the data collection, data analysis, and preparation of the manuscript. RA-BEAM and RA-BEGIN were designed by Eli Lilly and Company in consultation with an academic advisory board and Incyte Corporation.

Role of contributors

All authors participated in the interpretation of the results, and in the drafting, critical revision, and approval of the final version of the manuscript. ZC and BZ were also involved in the statistical analyses.

IMOR_1422232_Ishiguro_et_al_supplementary_figure_2.tif

Download TIFF Image (533.3 KB)IMOR_1422232_Ishiguro_et_al_supplementary_figure_1.tif

Download TIFF Image (536.4 KB)IMOR_1422232_Ishiguro_et_al_revised_supplementary_tables.docx

Download MS Word (50.1 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their deep gratitude to Jiaying Guo, MS, from Eli Lilly and Company for her assistance with the data analyses.

Funding

RA-BEAM and RA-BEGIN were supported by Eli Lilly and Company and Incyte Corporation. Medical writing assistance was provided by Luke Carey, PhD and Serina Stretton, PhD, CMPP of ProScribe–Envision Pharma Group, and was funded by Eli Lilly Japan K.K. ProScribe’s services complied with international guidelines for Good Publication Practice (GPP3).

References

- Tobon GJ, Youinou P, Saraux A. The environment, geo-epidemiology, and autoimmune disease: rheumatoid arthritis. J Autoimmun. 2010;35:10–14.

- Yamanaka H, Sugiyama N, Inoue E, Taniguchi A, Momohara S. Estimates of the prevalence of and current treatment practices for rheumatoid arthritis in Japan using reimbursement data from health insurance societies and the IORRA cohort (I). Mod Rheumatol. 2014;24:33–40.

- Carr A, Hewlett S, Hughes R, Mitchell H, Ryan S, Carr M, et al. Rheumatology outcomes: the patient’s perspective. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:880–3.

- Strand V, Cohen S, Crawford B, Smolen JS, Scott DL. Leflunomide Investigators G. Patient-reported outcomes better discriminate active treatment from placebo in randomized controlled trials in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43:640–7.

- Pollard L, Choy EH, Scott DL. The consequences of rheumatoid arthritis: quality of life measures in the individual patient. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23:S43–S52.

- Klarenbeek NB, Guler-Yuksel M, van der Kooij SM, Han KH, Ronday HK, Kerstens PJ, et al. The impact of four dynamic, goal-steered treatment strategies on the 5-year outcomes of rheumatoid arthritis patients in the BeSt study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1039–46.

- Sruamsiri R, Mahlich J, Tanaka E, Yamanaka H. Productivity loss of Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis - a cross-sectional survey. Mod Rheumatol. 2017. [Epub ahead of print]. doi:10.1080/14397595.2017.1361893

- Sakai R, Hirano F, Kihara M, Yokoyama W, Yamazaki H, Harada S, et al. High prevalence of cardiovascular comorbidities in patients with rheumatoid arthritis from a population-based cross-sectional study of a Japanese health insurance database. Mod Rheumatol. 2016;26:522–8.

- Smolen JS, Breedveld FC, Burmester GR, Bykerk V, Dougados M, Emery P, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: 2014 update of the recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:3–15.

- Aletaha D, Landewe R, Karonitsch T, Bathon J, Boers M, Bombardier C, et al. Reporting disease activity in clinical trials of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: EULAR/ACR collaborative recommendations. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1360–4.

- Anderson J, Caplan L, Yazdany J, Robbins ML, Neogi T, Michaud K, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis disease activity measures: American College of Rheumatology recommendations for use in clinical practice. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:640–7.

- Stoffer MA, Schoels MM, Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Breedveld FC, Burmester G, et al. Evidence for treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: results of a systematic literature search update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:16–22.

- Taylor PC, Moore A, Vasilescu R, Alvir J, Tarallo M. A structured literature review of the burden of illness and unmet needs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a current perspective. Rheumatol Int. 2016;36:685–95.

- Cutolo M, Kitas GD, van Riel PL. Burden of disease in treated rheumatoid arthritis patients: going beyond the joint. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;43:479–88.

- Gossec L, Dougados M, Dixon W. Patient-reported outcomes as end points in clinical trials in rheumatoid arthritis. RMD Open. 2015;1:e000019.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance for Industry. Patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. 2009. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidances/ucm193282.pdf [last accessed 28 August 2017].

- Fleischmann R, Strand V, Wilkinson B, Kwok K, Bananis E. Relationship between clinical and patient-reported outcomes in a phase 3 trial of tofacitinib or MTX in MTX-naive patients with rheumatoid arthritis. RMD Open. 2016;2:e000232.

- Olsen CL, Lie E, Kvien TK, Zangi HA. Predictors of fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis patients in remission or in a low disease activity state. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68:1043–8.

- Curtis JR, Shan Y, Harrold L, Zhang J, Greenberg JD, Reed GW. Patient perspectives on achieving treat-to-target goals: a critical examination of patient-reported outcomes. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65:1707–12.

- Radner H, Smolen JS, Aletaha D. Remission in rheumatoid arthritis: benefit over low disease activity in patient-reported outcomes and costs. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16:R56.

- Tang AC, Kim H, Crawford B, Ishii T, Treuer T. The use of patient-reported outcome measures for rheumatoid arthritis in Japan: a systematic literature review. Open Rheumatol J. 2017;11:43–52.

- Taylor PC, Keystone EC, van der Heijde D, Weinblatt ME, Del Carmen Morales L, Reyes Gonzaga J, et al. Baricitinib versus placebo or adalimumab in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:652–62.

- Fleischmann R, Schiff M, van der Heijde D, Ramos-Remus C, Spindler A, Stanislav M, et al. Baricitinib, methotrexate, or combination in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and no or limited prior disease-modifying antirheumatic drug treatment. Arthritis. Rheumatology. 2017;69:506–17.

- Keystone EC, Taylor PC, Tanaka Y, Gaich C, DeLozier AM, Dudek A, et al. Patient-reported outcomes from a phase 3 study of baricitinib versus placebo or adalimumab in rheumatoid arthritis: secondary analyses from the RA-BEAM study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1853–61.

- Schiff M, Takeuchi T, Fleischmann R, Gaich CL, DeLozier AM, Schlichting D, et al. Patient-reported outcomes of baricitinib in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and no or limited prior disease-modifying antirheumatic drug treatment. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19:208.

- Felson DT, Smolen JS, Wells G, Zhang B, van Tuyl LH, Funovits J, et al. American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism provisional definition of remission in rheumatoid arthritis for clinical trials. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:573–86.

- Kojima M, Kojima T, Suzuki S, Takahashi N, Funahashi K, Asai S, et al. Patient-reported outcomes as assessment tools and predictors of long-term prognosis: a 7-year follow-up study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2017;20:1193–1200.

- Wells GA, Tugwell P, Kraag GR, Baker PR, Groh J, Redelmeier DA. Minimum important difference between patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the patient's perspective. J Rheumatol 1993;20:557–60.

- Keystone E, Burmester GR, Furie R, Loveless JE, Emery P, Kremer J, et al. Improvement in patient-reported outcomes in a rituximab trial in patients with severe rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:785–93.

- Strand V, Singh JA. Newer biological agents in rheumatoid arthritis: impact on health-related quality of life and productivity. Drugs. 2010;70:121–45.

- Kobayashi Y, Ikeda K, Nakamura T, Yamagata M, Nakazawa T, Tanaka S, et al. Severity and diurnal improvement of morning stiffness independently associate with tenosynovitis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0166616.

- Kaneko Y, Takeuchi T, Cai Z, Sato M, Awakura K, Gaich C, et al. Determinants of Patient?s Global Assessment of Disease Activity and Physician?s Global Assessment of Disease Activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A post hoc analysis of overall and Japanese results from phase 3 clinical trials. Mod Rheumatol. 2017. [Epub ahead of print]. doi:10.1080/14397595.2017.1422304

- Matcham F, Scott IC, Rayner L, Hotopf M, Kingsley GH, Norton S, et al. The impact of rheumatoid arthritis on quality-of-life assessed using the SF-36: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;44:123–30.

- Fautrel B, van de LM, Kirkham B, Alten R, Cseuz R, Van der Geest S, et al. Differences in patient-reported outcomes between baricitinib and comparators among patients with rheumatoid arthritis who achieved low disease activity or remission. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(Suppl. 2):230.