Abstract

Objectives: The objective of this study is to develop clinical practice guideline (CPG) for Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) based on recently available clinical and therapeutic evidences.

Methods: The CPG committee for SS was organized by the Research Team for Autoimmune Diseases, Research Program for Intractable Disease of the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (MHLW), Japan. The committee completed a systematic review of evidences for several clinical questions and developed CPG for SS 2017 according to the procedure proposed by the Medical Information Network Distribution Service (Minds). The recommendations and their strength were checked by the modified Delphi method. The CPG for SS 2017 has been officially approved by both Japan College of Rheumatology and the Japanese Society for SS.

Results: The CPG committee set 38 clinical questions for clinical symptoms, signs, treatment, and management of SS in pediatric, adult and pregnant patients, using the PICO (P: patients, problem, population, I: interventions, C: comparisons, controls, comparators, O: outcomes) format. A summary of evidence, development of recommendation, recommendation, and strength for these 38 clinical questions are presented in the CPG.

Conclusion: The CPG for SS 2017 should contribute to improvement and standardization of diagnosis and treatment of SS.

Introduction

Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) is an autoimmune disease characterized by lymphocytic infiltration into the exocrine glands and other organs, leading to dry mouth, dry eyes, and various extra-glandular symptoms [Citation1]. SS is categorized into primary SS (pSS) which is not associated with other well defined connective tissue diseases (CTDs), and secondary SS, which is associated with other well defined CTDs [Citation1]. Moreover, pSS is further subdivided into the glandular form, with involvement of the exocrine glands only, and the extra-glandular form, with the involvement of organs other than exocrine glands.

In Japan, SS was certified as a designated intractable disease by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (MHLW) in January 2015. Researches on designated intractable diseases are organized and supported by the Research Program for Intractable Disease of MHLW and the Practical Research Project for Rare/Intractable Diseases from Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED). The Research Program for Intractable Disease of MHLW provides support for epidemiological studies, establishes diagnostic and severity criteria, develops clinical practice guideline (CPG) based on clinical and therapeutic evidences, and distributes and revises these criteria and CPG. On the other hand, the Practical Research Project for Rare/Intractable Diseases from AMED supports clinical research on gene therapy and clinical application of new therapies and medical devices, and provides financial support for physician-led clinical trials. Moreover, patients with designated intractable diseases can obtain medical expenses subsidy once they satisfy certain diagnostic and severity criteria.

Therefore, standardization of diagnosis and treatment of SS is needed for appropriate management and accurate certification of designated intractable disease. CPG based on recently available evidences should also contribute to standardization of clinical practices across the country. The treatment guideline by the SS Foundation of the United States of America (USA) [Citation2] and the management guideline for SS by the British Society for Rheumatology (BSR) [Citation3] were published recently. Moreover, the CPG committee for SS, organized by the Research Team for Autoimmune Diseases, the Research Program for Intractable Disease of MHLW, has developed ‘CPG for SS 2017’ [Citation4] which has been officially approved by both the Japan College of Rheumatology (JCR) and the Japanese society for SS (JSSS), according to the procedure proposed by the Medical Information Network Distribution Service (Minds) [Citation5].

In this review, the development process, summary of evidences, development of recommendations, clinical questions and recommendations, and strengths of recommendation of the CPG for SS 2017 are summarized by the CPG committee and collaborators.

CPG development process

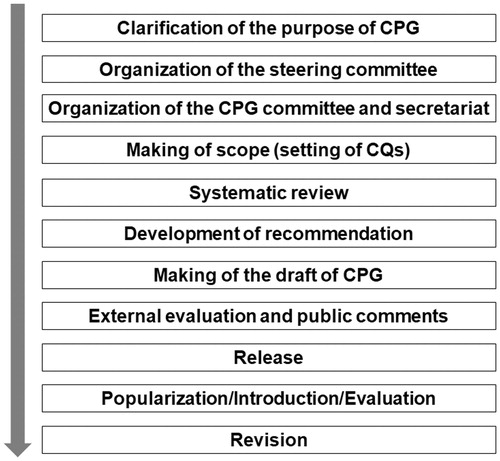

The CPG committee for SS organized by the Research Team for Autoimmune Diseases, the Research Program for Intractable Disease of MHLW (Principal Investigator: Prof. Takayuki Sumida) has developed CPG for SS 2017, according to the procedure proposed by Minds [Citation5]. The CPG development process included (1) clarification of the purpose of CPG, (2) organization of the steering committee, (3) organization of the CPG committee and secretariat, (4) setting the scope of the clinical questions, (5) systematic review, (6) development of recommendation, (7) writing the first draft of CPG, (8) external evaluation and public comments, and (9) release of the CPG ().

Clarification of purpose of CPG

The CPG was developed to support decision making in clinical practice about clinical symptoms and signs, treatment, and management of SS during pregnancy/parturition, for all health care professionals who are involved in the clinical management of SS, including family physicians, rheumatologists, ophthalmologists, dental and oral surgeons, otolaryngologists, pediatricians, and health professionals other than physicians. The purpose of the CPG was to enhance diagnosis, help in evaluation of disease activity, and provision of early and effective treatment of SS.

Organization of the steering committee

The steering committee was organized by 13 multidisciplinary clinical research scientists (eight rheumatologists, two ophthalmologists, two dental and oral surgeons, and one public health scholar) of the Research Team for Autoimmune Diseases, the Research Program for Intractable Disease of MHLW.

Organization of the CPG committee and secretariat

Other four collaborators (two rheumatologists, one otolaryngologist, and one pediatrician) joined with 13 steering committee members described above to establish the 17-member CPG committee.

Setting scope of clinical questions

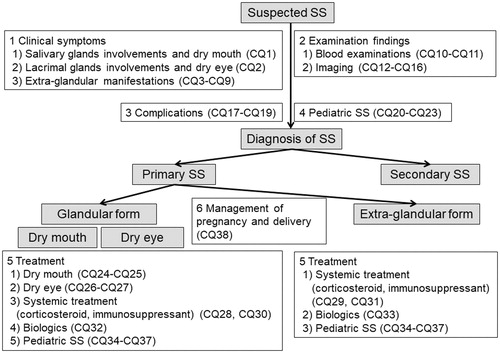

The CPG committee set 38 clinical questions on three important SS-related clinical issues, including clinical symptoms and signs, treatment, and management of female patients with SS during pregnancy and delivery, using the PICO (P: patients, problem, population, I: interventions, C: comparisons, controls, comparators, O: outcomes) format ( and ). The relationship between the algorithm of SS clinical practice and each of the clinical questions is shown in .

Figure 2. Relationship between algorithm of clinical practice for Sjögren’s syndrome and each clinical question. CQ: clinical question; SS: Sjögren’s syndrome.

Table 1. Setting of clinical questions using the PICO format (clinical question 28 is used here as an example).

Table 2. Summary of clinical questions and recommendations.

Systematic review

Another group of 14 collaborators from institutions in which each CPG committee member worked at joined the 17 CPG committee members to form the Systematic Review team. The team independency was guaranteed; the 17-CPG committee members reviewed evidences on clinical questions, which were different from those they worked in setting of clinical questions. Literature search was performed by The Japan Medical Library Association (JMLA) using the following medical databases; National Guideline Clearinghouse (NCG), NICE Evidence Search, Minds guideline center, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, PubMed, The Cochrane Library, and Igaku Chuo Zasshi (ICHUSHI) of the Japan Medical Abstracts Society (JAMAS), based on English or Japanese keywords listed from each PICO formatted clinical questions. The Systematic Review team members performed the first and the second screening of the literature, evaluated, and integrated the evidences, and wrote the Systematic Review reports. The strength of body of evidence for each clinical outcome was evaluated according to the methods proposed by Minds [Citation5], such as A (strong), B (moderate), C (weak), and D (very weak).

Development of recommendation

The CPG committee members scored the overall evidence for each clinical question, such as A (strong), B (moderate), C (weak), and D (very weak), by integrating the body of evidence for each outcome, based on the Systematic Review report and evidence evaluation sheets produced by the Systematic Review team members. Not only the strength of evidence and balance between benefits and harm but also diversity of patients’ sense of value and economical viewpoints were considered in the development of recommendations. The recommendations and strengths of recommendations (strong or weak) were carefully itemized by the 17 CPG committee members using the modified Delphi method with a minimum of 70% agreement (12 of the 17 members) required for consensus. Revision of recommendations that did not achieve consensus was permitted for up to four rounds. The course of development of recommendation, including advantages and limitations of the adopted studies, summary of the systematic review, application in health insurance, and final decision appear as explanations in the CPG.

Writing first draft of CPG

The draft of CPG was written and organized in five chapters, including organization and development process, scope, recommendations, activities after release, and appendix (collected evidence data).

External evaluation and public comments

External evaluation and public comments on the draft of CPG were collected from the JCR and JSSS. A revised CPG was prepared taking into consideration the above evaluations, and the final version of CPG was approved by the CPG committee as well as both the JCR and JSSS.

Release of CPG

‘CPG for SS 2017’ was reported by The Research Team for Autoimmune Diseases, The Research Program for Intractable Disease of MHLW on March 2017, and also published in Japan in a book format in April 2017 [Citation4].

Clinical questions and recommendations

Below are 38 clinical questions related to the diagnosis and treatment of SS in pediatric, adult and pregnant patients. For each question, clinical question and recommendation made by the committee are presented first, followed by a summary of evidence, and ending by detailed explanation of the material used for the development of recommendation.

Clinical question 1

1.1. Which oral tests and procedures can be used for the diagnosis and clinical decision making in SS?

1.2. Recommendations: It has been recommended that unstimulated whole saliva, Saxon test, Gum test, and labial salivary gland biopsy are useful for the diagnosis and clinical decision making on SS (Strength of recommendation; Strong).

1.3. Summary of evidence: Systematic review included five cross-sectional studies [Citation6–10], six cohort studies [Citation11–16], and one case series study [Citation17]. In these studies, the reported sensitivities and specificities for the diagnosis of SS ranged from 83% to 87% and 79% to 87% for the Gum test [Citation6,Citation7,Citation10], 65–79% and 50–79% for the unstimulated whole saliva (UWS) [Citation7,Citation10,Citation13], 78–84% and 82–100% for the labial salivary glands (LSGs) biopsy [Citation9,Citation13,Citation15], and 78% and 86% for parotid gland biopsy [Citation15]. Although the data for sensitivity and specificity of Saxon test were not available, the results of the test were found in one cross-sectional study to correlate significantly with those of the Gum test [Citation6] (Strength of evidence; D).

In one retrospective cohort study [Citation11], a focus score of ≥3 in LSGs biopsy was an independent predictive risk factor for the development of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) in primary SS, and patients with focus score ≥3 had significantly higher EULAR SS Disease Activity Index (ESSDAI) and extra-glandular manifestations score. Two cohort studies [Citation12,Citation14] reported that the successful sampling rate was high (90–98%) for LSGs biopsy (D). In four studies [Citation12,Citation14,Citation15,Citation17], the rate of complications associated with LSGs biopsy ranged from 0% to 10% (Strength of evidence; D).

Thus, the Gum test, UWS, Saxon test, LSGs biopsy, and parotid glands biopsy seem to help in establishing accurate diagnosis of SS. LSGs biopsy is useful for clinical decision making of SS because it has good sampling rate and can predict extra-glandular manifestations and development of NHL in SS.

1.4. Development of recommendations: Systematic review of the published material indicated that the UWS, Saxon test, Gum test, LSGs biopsy, and parotid gland biopsy can help in the establishment of accurate diagnosis of SS. Although the tests and procedures seem to be relatively safe, only LSGs biopsy is recommended, since parotid gland biopsy is associated with a few risks of facial nerve injury and requires certain level of expertise (Strength of evidence; D).

Clinical question 2

2.1. Which ophthalmic tests are useful for diagnosis and selection of treatment?

2.2. Recommendation: It has been suggested that the Schirmer test, Tear film break-up time (TFBUT), Rose Bengal test, Lissamine Green test and Fluorescein test improve the rate of diagnosis and understanding disease condition (Strength of recommendation; Weak).

2.3. Summary of evidence: Three observational studies on the Schirmer test and TFBUT [Citation18–20], two observational studies on the Rose Bengal test [Citation21,Citation22] and one observational study on the Lissamine Green test [Citation20] and the fluorescein test [Citation19] were systematically reviewed. All tests showed that the clinical findings were significantly worse in patients with SS than in subjects with non-SS, suggesting that these ophthalmic tests are useful for improving the rate of diagnosis and understanding disease condition in SS (Strength of evidence; D). Regrettably, the above studies did not assess the usefulness of these ophthalmic tests for the determination of treatment policy, early treatment, and adverse events [Citation18–22]. Based on the systematic review, it is suggested that the Schirmer test, TFBUT, Rose Bengal test, Lissamine Green test, and the fluorescein test are useful for improving the rate of diagnosis and understanding disease condition in SS.

2.4. Development of recommendation: Systematic review of five observational studies on the Schirmer test, TFBUT, Rose Bengal test, Lissamine Green test, and fluorescein test indicated that these tests can improve the rate of diagnosis and understanding disease condition in SS (Strength of evidence; D). There are currently no meta-analysis studies on randomized controlled trials (RCT) or large-population studies. Since the CPG committee places high priority for less invasive tests, the following is the substatement on the above tests: although the following tests are all useful for the diagnosis of SS, the CPG committee suggests priority should be given to the fluorescein test, Lissamine Green test, and Rose Bengal test, in that order, considering the invasiveness of the tests.

Clinical question 3

3.1. What are the extra-glandular manifestations that influence prognosis of SS?

3.2. Recommendation 3: There is no specific extra-glandular manifestation known to influence prognosis. However, it has been suggested that the presence of extra-glandular manifestations should be considered a risk factor for poor prognosis (Strength of recommendation; Weak).

3.3. Summary of evidence: One meta-analysis of 10 cohort studies [Citation23] was evaluated by the Systematic Review committee. The 10 studies included 7,888 patients with pSS, of whom 682 died after a median follow-up of 9 years. The meta-analysis concluded that the mortality risk of pSS is not different from that in the general population [standardized mortality rate: 1.38 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.94, 2.01)] [Citation23]. The leading causes of mortality in SS were cardiovascular diseases, solid-organ and lymphoid malignancies, and infections [Citation23]. The presence of extra-glandular manifestations was found to be a risk factor for increased mortality [relative risk 1.77 (95% CI 1.06, 2.95)]. Unfortunately, comparative analysis of the effects of each extra-glandular manifestation on prognosis was not conducted [Citation23]. Furthermore, the duration of the observation and follow-up, and treatment modalities varied in the 10 observational cohort studies. Based on these inconsistencies and the heterogeneity in the reported information, it was assumed that the risk of bias in the meta-analysis study was significantly higher than that in a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [Citation23]. However, apart from this meta-analysis, the literature search identified only narrative reviews or small-scale observational studies. Therefore, this was considered a study with the highest evidence level.

3.4. Development of recommendation: The systematic review showed lack of studies that investigated the effects of specific extra-glandular manifestations on prognosis. However, one heterogeneous meta-analysis concluded that the presence of extra-glandular manifestations is a risk factor for increased mortality (Strength of evidence; C). Thus, the CPG committee considers that the clinical management should be based on these findings.

Clinical question 4

4.1. What are the characteristic cutaneous manifestations of SS?

4.2. Recommendation: Annular erythema and cutaneous vasculitis have been considered characteristic cutaneous manifestations of SS (Strength of recommendation; Weak).

4.3. Summary of evidence: There are only a few epidemiologic studies on extra-glandular manifestations of pSS. Only recommendation of the EULAR-SS Task Force was adopted as the latest and most comprehensive. The recommendation included currently available evidence obtained through systematic literature review that focused on SS-related systemic involvement based on the ESSDAI classification, and was published as the best recommendation for diagnosis [Citation24]. Annular erythema and cutaneous vasculitis were considered characteristic cutaneous manifestations [Citation24]. With regard to annular erythema, its prevalence in patients with pSS was 9%; and affected the face (61% of the cases), upper arm (34%), trunk (12%), neck (25%), lower arm (16%), and disseminated (11%) lesion. The histopathological features of annular erythema include perivascular lymphocytic infiltration (100%), periependymal lymphocytic infiltration (60%), positive indirect immunofluorescence (57%), and epidermal changes (29%) [Citation24]. On the other hand, the prevalence of cutaneous vasculitis in patients with pSS was 10%; and was clinically seen together with cutaneous purpura (88%), cutaneous ulcers (9%), and urticarial vasculitis (7%). The histopathological findings include leukocytoclastic vasculitis (90%), lymphocytic vasculitis (2%), capillaritis (2%), microthrombosis (2%), and necrotizing vasculitis (4%) [Citation24].

4.4. Development of recommendation: Systematic review indicated that only the EULAR-SS Task Force recommendations considered annular erythema and cutaneous vasculitis as characteristic cutaneous lesions of SS, though their report did not include information on the sensitivity and specificity (Strength of evidence; C). Based on the above, the CPG committee considered cutaneous vasculitis a characteristic cutaneous lesion in SS. While the histopathological findings are important, it was considered that the patient (and family) is less likely to accept a skin biopsy based on the invasive nature and cost of the procedure.

Clinical question 5

5.1. What are the characteristic renal manifestations of SS?

5.2. Recommendation: Tubulointerstitial nephritis and renal tubular acidosis have been considered characteristic SS renal lesions, followed by glomerulonephritis (Strength of recommendation; Weak).

5.3. Summary of evidence: There have been few epidemiologic studies on extraglandular manifestations of primary SS (pSS). Only the EULAR-SS Task Force recommendation [Citation24] was adopted as the latest and most comprehensive. The recommendation was based on currently available evidence based on systematic literature review that focused on SS-related systemic involvement according to the ESSDAI classification, and published as an optimal recommendation for diagnosis [Citation24]. The characteristic renal involvement in SS was tubulointerstitial nephritis/renal tubular acidosis (RTA) and glomerulonephritis (GN) [Citation24]. With regard to tubulointerstitial nephritis/RTA in pSS patients, it showed a prevalence of 9%; with 97% of patients classified as RTA type 1 and 3% as type 2; with hypokalemic weakness/paralysis (in 69% of the patients), renal colic (12%), radiological nephrocalcinosis (17%), osteomalacia (13%), polyuria/polydipsia (4%), and renal failure (creatinine >1.3 mg/dl) (24%) at clinical presentation, and histopathologically showing tubulointerstitial nephritis (93%) [Citation24]. With regard to GN, the reported prevalence in pSS is 4%, the clinical presentation includes edema/nephrotic syndrome (in 22% of pSS patients), laboratory abnormalities (78%); renal failure (creatinine >1.3 mg/dl) (50%), proteinuria (0.5–1 g/24 h) (11%), proteinuria (1–1.5 g/24 h) (19.5%), proteinuria >1.5 g/24 h (69.5%), hematuria (51%) [Citation24]; and histopathological examination showed predominantly membranoproliferative GN (38%), mesangial proliferative GN (23%), and membranous GN (22%) [Citation24].

5.4. Development of recommendation: Systematic review of the literature indicated that tubulointerstitial nephritis/RTA and GN are characteristic renal lesions. Tubulointerstitial nephritis/RTA was more than twice as common as GN as reported in the EULAR-SS Task Force recommendations, although they did not report the sensitivity and specificity (Strength of evidence; C). The CPG committee adopted the EULAR-SS Task Force recommendation. However, it is likely that approval of renal biopsy by the patient (and family) will be inconsistent due to the invasive nature of the procedure and high cost, compared with urinalysis and blood tests.

Clinical question 6

6.1. What are the characteristic peripheral nerve manifestations of SS?

6.2. Recommendation: It has been suggested that polyneuropathy and cranial neuropathy are characteristic peripheral nerve lesions in SS, followed by mononeuritis multiplex (Strength of recommendation; Weak).

6.3. Summary of evidence: Only a few epidemiologic studies have evaluated extra-glandular manifestations of pSS, and to date, there are no published RCTs, systematic reviews, or meta-analyses studies of peripheral nerve involvement (PNI) in pSS. Only one report by Gono et al. [Citation25] discussed the types and prevalence of PNI [Citation25]. Their single-center, retrospective cohort study found PNI in 53% of their patients diagnosed with pSS during the period of 1992–2008 [Citation25]. PNI included cranial neuropathy (41%; optic neuritis 18%, trigeminal neuralgia 12%, facial nerve palsy 6%, glossopharyngeal and vagus nerve palsy 6%), polyneuropathy (53%; pure sensory 47%, motor-sensory 6%), and mononeuritis multiplex (18%; motor-sensory 12%, pure sensory 6%). Vasculitis, ganglioneuritis, and the appearance of autoantibodies (including anti-aquaporin-4 antibody, antibody to small neuronal cells in the dorsal root ganglion, and anti-M3-muscarinic receptor antibody) were associated with PNI [Citation25]. This report was considered low-level evidence with a high risk of bias, high inconsistency, and moderate indirectness. However, there were no similar epidemiologic studies. Accumulation of further cases in larger prospective cohort studies is necessary.

6.4. Development of recommendation: The characteristic PNI seems to include polyneuropathy, cranial neuropathy, and mononeuritis multiplex. Polyneuropathy and cranial neuropathy were approximately three times and more than twice as frequent as mononeuritis multiplex, respectively, but this was reported in only one single-center, retrospective cohort study, which did not comment on the sensitivity and specificity (Strength of evidence; C). Based on this evidence, the CPG committee recommended these findings. However, patient (and family) acceptance of nerve biopsy is predicted to be inconsistent due to the invasive nature of the procedure and cost compared with nerve conduction velocity and blood tests.

Clinical question 7

7.1. What are the characteristic manifestations of central nervous system involvement in SS?

7.2. Recommendation: Encephalopathy and aseptic meningitis have been considered the most common manifestations of central nervous system involvement in SS, followed by cerebral white matter and spinal cord lesions, typically with symptoms of headache, cognitive disorders, and mood disorders (Strength of recommendation; Weak).

7.3. Summary of evidence: Two epidemiologic cohort studies of central nervous system involvement (CNSi) in pSS have been published [Citation25,Citation26]. Both studies showed moderate indirectness, and the risk of bias and inconsistency was high (Strength of evidence; C). One single-center, retrospective cohort study conducted from 1992 to 2008 [Citation25] reported the diagnosis of CNSi in 19% of pSS patients. CNSi included encephalopathy (in 50% of the patients), aseptic meningitis (33%), and cerebral white matter and spinal cord lesions (17%). Another single-center, cohort study conducted from 2010 to 2013 [Citation26] reported CNSi and peripheral nerve involvement (PNI) in 67.5% of pSS patients. For CNSi, non-focal neurological symptoms were significantly more common (84%) than focal neurological deficits (79%) (p = .005). CNSi was significantly more prevalent than PNI (53%) (p = .001). Headache was the most common symptom (46.9%), followed by cognitive disorders (44.4%) and mood disorders (38.3%).

7.4. Development of recommendation: Systematic review of the above two single-center, cohort studies indicated that the characteristic CNSi in pSS included encephalopathy, aseptic meningitis, and cerebral white matter and spinal cord lesions as confirmed by pathological and histopathological assessment, and that functional disorders included headache, cognitive disorders, and mood disorders. In addition, encephalopathy and aseptic meningitis were approximately three and two times more common in these patients than cerebral white matter and spinal cord lesions, respectively. These two studies did not report the sensitivity and the specificity (Strength of evidence; C). The CPG committee recommends the findings of these reports. However, poor acceptance of imaging assessment, blood tests, and cerebrospinal fluid examination by the patient (and family) is predicted due to invasiveness and cost of these studies.

Clinical question 8

8.1. What are the characteristic manifestations of pulmonary lesions in SS?

8.2. Recommendation: Small airway disease and interstitial lung disease have been considered the characteristic pulmonary lesions in SS (Strength of recommendation; Weak).

8.3. Summary of evidence: There are only a few epidemiologic studies on extra-glandular manifestations of pSS, but only the EULAR-SS Task Force recommendation [Citation24] was adopted as the latest and most comprehensive. The recommendation included currently available evidence obtained through systematic literature review that focused on SS-related systemic involvement, using the ESSDAI classification, and was published as the optimal recommendation for diagnosis [Citation24]. The prevalence of pulmonary involvement in patients with pSS was 16% [Citation24]. Pulmonary involvement was described to present clinically with dyspnea (in 62% of the patients), cough (54%), sputum/rales (14%), chest pain (5%), and fever (2%) [Citation24]. In the same report, pulmonary function tests (PFT) showed restrictive pattern (64%) and less commonly, obstructive pattern (21%) [Citation24]. High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) showed bronchiectasis/bronchiolectasis/bronchiolar abnormalities (50%) and ground glass opacities/interstitial changes (49%) [Citation24]. Histopathological examination showed predominantly nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) (45%), bronchiolitis (25%), usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) (16%), and lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia (LIP) (15%) [Citation24].

8.4. Development of recommendation: Systematic review indicated that the characteristic pulmonary complications in pSS are restrictive and obstructive patterns on PFT; bronchiectasis, bronchiolectasis, bronchiolar abnormalities and ground glass opacities/interstitial changes on HRCT; and NSIP, bronchiolitis, UIP, and LIP on histopathological findings. These were described only in the EULAR-SS Task Force recommendations, which did not describe the sensitivity and specificity (Strength of evidence; C). Based on the above study, the CPG committee adopted the above recommendations based on PFT, HRCT, and histopathological findings. However, poor acceptance of imaging assessment and bronchoscopy for lung biopsy by the patient (and family) is predicted due to invasiveness and cost of these studies.

Clinical question 9

9.1. What are the characteristic articular involvements in SS?

9.2. Recommendation: Symmetrical polyarthritis with involvement of fewer than five joints, absence of radiographic bone erosions, and negative anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibody have been considered characteristic articular manifestations in pSS (Strength of recommendation; Weak).

9.3. Summary of evidence: While there are few epidemiological studies on extra-glandular manifestations of pSS, only the EULAR-SS Task Force recommendation [Citation24] was adopted by the Systematic Review committee as the latest and most comprehensive. The EULAR-SS Task Force recommendation included currently available evidence obtained through systematic literature review that focused on SS-related systemic involvement, based on the ESSDAI classification, and was published as an optimal recommendation for the diagnosis of articular involvement [Citation24]. Arthritis was diagnosed in 16% of pSS patients [Citation24]; and symmetrical arthritis was more common (71%) than monoarthritis (17%) [Citation24]. Involvement of fewer than five joints (88%) was more common than involvement of five or more (12%) [Citation24]. Arthritis was located in the proximal interphalangeal joints (in 35% of the patients), metacarpophalangeal joints (35%), wrists (30%), elbows (15%), knees (10%), ankles (10%), shoulders (6%), metatarsophalangeal joints (5%), and distal interphalangeal joints (3%) [Citation24]. Radiographic bone erosions and positive anti-CCP antibody were infrequent and only found in 5% and 7%, respectively [Citation24].

9.4. Development of recommendation: Systematic review indicated that symmetrical polyarthritis involving fewer than five joints and infrequent presence of radiographic bone erosions or positive anti-CCP antibody are characteristic articular manifestations in pSS as reported in the EULAR-SS Task Force recommendations, although they did not report the sensitivity and specificity (Strength of evidence; C). Based on these findings, the CPG committee adopted the above recommendations.

However, poor acceptance of imaging assessment and blood tests by the patient (and family) is predicted due to the cost of these studies despite minimal invasiveness.

Clinical question 10

10.1. Are autoantibodies useful for the diagnosis of SS?

10.2. Recommendation: Evaluation of anti-SS-A/Ro and anti-SS-B/La antibodies has been recommended for a firm diagnosis of SS, especially in patients with symptoms of dryness (Strength of recommendation; Strong).

10.3. Summary of evidence: Systematic review of 12 observational studies was conducted, including seven cohort studies [Citation13,Citation27–32] and five cross-sectional studies [Citation33–37]. No RCT was identified in the literature search. One study reported the sensitivity and specificity of anti-SS-A and/or anti-SS-B antibodies, rheumatoid factor, and anti-nuclear antibody [Citation13]. Another study described the correlation between anti-SS-A/B antibodies and the titer of anti-nuclear antibody (more than 1:640) [Citation28]. No data are available on the sensitivity and specificity of anti-centromere antibody and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody (anti-CCP antibody) (Strength of evidence; D). One cohort study [Citation29] showed the relationship between anti-SS-A/B antibodies and the scores of minor salivary gland biopsies. One cross-sectional study [Citation37] reported the relationship between anti-SS-B antibody titer and saliva production rate. Another cohort study showed that a positive anti-centromere antibody correlated with low incidence of dry eye, hypergammaglobulinemia, anti-SS-A/B antibodies, and high incidence of Raynaud phenomenon and dysphagia [Citation32]. One cross-sectional study [Citation35] described a relationship between anti-CCP antibody and non-erosive arthritis. According to these studies, it is suggested that evaluation of anti-SS-A/B antibodies and anti-nuclear antibody can improve the sensitivity and specificity of the diagnosis of SS. On the other hand, the diagnostic values of anti-centromere antibody and anti-CCP antibody remain unknown at this stage.

10.4. Development of recommendation: Based on the information available in the literature, it seems that evaluation of anti-SS-A/Ro and anti-SS-B/La antibodies can be helpful in the diagnosis of SS, especially in patients with dryness-related symptoms. Moreover, expert opinions call for simultaneous evaluation of anti-nuclear antibody. However, the usefulness of anti-centromere and anti-CCP antibodies in the diagnosis of SS remains unknown.

Clinical question 11

11.1. Which blood tests are useful for the diagnosis of SS?

11.2. Recommendation: It has been recommended that blood tests should be performed to confirm the presence of cytopenia and hypergammaglobulinemia (Strength of recommendation; Weak).

11.3. Summary of evidence: Systematic review targeted six observational studies, including three cross-sectional studies [Citation38–40], two cohort studies [Citation41,Citation42] and one case–control study [Citation43]. No RCT study has been published on the topic. Furthermore, no data are available about the sensitivity and specificity of hematological tests (Strength of evidence; D). One case–control study [Citation43] showed significantly higher frequency of leukopenia among SS patients complicated with systemic lupus erythematosus than those without such complication (Strength of evidence; D). Only a small percentage of patients with SS in one cohort study [Citation41], who also had Hashimoto thyroiditis, had low complement and malignant lymphoma (Strength of evidence; D). One cross-sectional study reported possible relation between skin rashes and thrombocytopenia [Citation39]. Another cross-sectional study showed lower frequency of lymphopenia in SS patients with liver dysfunction [Citation38]. One cross-sectional study showed no difference in frequency of thyroid disease between SS patients and sex- and age-matched control subjects (Strength of evidence; D) [Citation40]. Based on this information, the committee could not confirm the usefulness of blood tests in the diagnosis of SS.

11.4. Development of recommendation: Systematic review of the literature showed poor discussion on the usefulness of blood tests in the diagnosis and evaluation of severity of SS. In general, the evidence level was very weak (Strength of evidence; D). Expert opinion suggested the potential usefulness of cytopenia and hypergammaglobulinemia in the diagnosis of SS.

Clinical question 12

12.1. Which imaging modality is useful for evaluation of glandular lesions in SS?

12.2. Recommendation: Salivary gland ultrasonography (SGUS), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), salivary gland scintigraphy, and sialography have been recommended as useful imaging modalities for evaluation of glandular involvement in SS (Strength of recommendation; Weak).

12.3. Summary of evidence: Systematic review focused on 22 observational studies, including 15 case–control studies [Citation44–58], six case series studies [Citation57–63], and one miscellaneous study [Citation64]. No meta-analysis studies are available in the literature. With regard to the diagnosis of SS by SGUS, three studies rated its sensitivity at 82–98%, specificity at 69–95%, and accuracy at 77–92% [Citation44,Citation58,Citation65] (Strength of evidence; D). For MRI, three studies rated the sensitivity at 85–96% and specificity at 98–100% [Citation47,Citation48,Citation59] (Strength of evidence; D). Two of these studies did not provide data on sensitivity and specificity, while the diagnostic performance of MRI was rated equal to that of sialography in two studies [Citation48,Citation51] (Strength of evidence; D). For salivary gland scintigraphy, four studies rated the sensitivity at 83–100%, specificity at 49–80%, positive predictive value at 65–100%, negative predictive value at 69–91%, and accuracy at 69–72% [Citation52,Citation53,Citation55] (Strength of evidence; D). No data related to sensitivity and specificity are available on sialography.

12.4. Development of recommendation: The CPG committee suggests the usefulness of SGUS, MRI, salivary gland scintigraphy, and sialography for the diagnosis as well as the classification of severity of SS. However, some studies described difficulty of diagnosis of SS based on salivary gland scintigraphy alone.

Clinical question 13

13.1. To what extent can salivary gland ultrasonography (SGUS) contribute to the diagnosis, evaluation of severity, and response to treatment of SS?

13.2. Recommendation: SGUS has been considered useful for the diagnosis of glandular involvement and evaluation of severity (Strength of recommendation; Weak).

13.3. Summary of evidence: Five observational studies, including four case–control studies [Citation44,Citation57,Citation58,Citation65] and one case series study [Citation45], were the focus of systematic review. No meta-analysis studies have been published on this topic. With regard to the diagnosis of SS by SGUS, three studies rated its sensitivity at 82–98%, specificity at 69–95%, and accuracy at 77–92% [Citation44,Citation58,Citation65] (Strength of evidence; D). For the diagnosis of SS, SGUS was found to have the same diagnostic performance as sialography and labial salivary gland (LSG) biopsy [Citation44,Citation65] (Strength of evidence; D). SGUS was also found to be as effective as sialography in classifying the severity of SS [Citation57,Citation58] (Strength of evidence; D). One study reported that five classifications of severity were possible using SGUS [Citation45] (Strength of evidence; D). One case–control study suggested that SGUS could be useful for evaluating the response to therapy, although the results were not statistically significant [Citation45] (Strength of evidence; D).

13.4. Development of recommendation: The CPG committee suggests that the diagnostic performance of SGUS for SS is similar to that of sialography and LSG biopsy, while its usefulness to classify the severity is similar to that of sialography. SGUS seems useful for evaluation of the response to treatment.

Clinical question 14

14.1. Is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of salivary glands useful for the diagnosis of SS, evaluation of its severity, and responses to therapy?

14.2. Recommendation: MRI of salivary glands has been considered useful for the diagnosis of glandular involvement and evaluation of severity of SS (Strength of recommendation; Weak).

14.3. Summary of evidence: Six observational studies, including four case–control studies [Citation46–49] and two case series studies [Citation59,Citation64] were subjected to systematic review. No meta-analysis studies were retrieved on the search. Six studies showed that MRI was useful for the diagnosis of SS [Citation46–49,Citation59,Citation64], and three studies rated its sensitivity at 85–96% and specificity at 98–100% [Citation47,Citation48,Citation59] (Strength of evidence; D). Five studies [Citation46–48,Citation59,Citation64] indicated that MRI is as good as sialography in classifying the severity of SS (D), while two studies reported positive correlation between the classification of SS severity by the MRI and sialography [Citation46,Citation48] (Strength of evidence; D). One study rated the matching between the two methods in their classification of severity at 84% [Citation59] (Strength of evidence; D). The literature search showed no studies related to the use of MRI for the assessment of the response to treatment.

14.4. Development of recommendation: The CPG committee views MRI of salivary glands as useful for the diagnosis of SS. Although the classification of severity of SS by MRI is reported to be similar to that of sialography, the agreement rate between these two methods is not 100%.

Clinical question 15

15.1. Is salivary gland scintigraphy useful for the diagnosis of SS, evaluation of its severity and response to therapy?

15.2. Recommendation: Salivary gland scintigraphy has been considered useful for the diagnosis of glandular involvement in SS and evaluation of its severity (Strength of recommendation; Weak).

15.3. Summary of evidence: Eight observational studies, including six case–control studies [Citation50–55] and two case series studies [Citation60,Citation61] were identified on the literature search and systematically reviewed. No meta-analysis studies were found. With regard to the diagnosis of SS by salivary gland scintigraphy, three studies rated its sensitivity at 83–100%, specificity at 49–80%, positive predictive value at 65–100%, negative predictive value at 69–91%, and accuracy at 69–72% [Citation52,Citation53,Citation55] (Strength of evidence; D). For classification of severity, six studies reported that salivary gland scintigraphy can be used to quantify, through measurement of radioisotope (RI) intake rate and excretion volume [Citation50–52,Citation54,Citation60,Citation61] (Strength of evidence; D). Four studies reported positive correlation among the classification capacities of severity of SS among salivary gland scintigraphy, LSG biopsy, and salivary flow rate [Citation50,Citation52,Citation55,Citation61] (Strength of evidence; D). There are no studies on the usefulness of salivary gland scintigraphy in evaluation of response to treatment of SS.

15.4. Development of recommendation: The CPG committee advocates the use of salivary gland scintigraphy for the diagnosis of SS. Although assessment of the severity of SS glandular involvement by salivary gland scintigraphy is reported to be similar to that by LSG biopsy and salivary flow rate, the agreement rate among these methods is less than 100%. Moreover, the results of assessment of the different glands (submandibular gland versus parotid gland, or right versus left) indicate that the use of salivary gland scintigraphy alone for the diagnosis of SS could be problematic.

Clinical question 16

16.1. Is sialography useful for the diagnosis of SS, evaluation of severity, and response to treatment?

16.2. Recommendation: Sialography has been considered useful for the diagnosis of glandular involvement and evaluation of severity of SS (Strength of recommendation; Weak).

16.3. Summary of evidence: The literature search identified five observational studies, including one case–control study [Citation56], three case series studies [Citation57,Citation62,Citation63], and one other type of study [Citation64], but no meta-analysis studies. Systematic review of these studies showed that sialography was used as a diagnostic tool in four studies, but no concrete conclusions were formulated regarding its sensitivity and specificity in the diagnosis of SS [Citation56,Citation57,Citation62,Citation63] (Strength of evidence; D). Four studies reported that sialography could accurately classify the severity of SS based on the classification of Rubin & Holt [Citation56,Citation57,Citation62,Citation63] (Strength of evidence; D). To date, there are no studies that examined the utility of sialography in the assessment of the response to therapy.

16.4. Development of recommendation: The CPG committee advocates the application of sialography for the diagnosis and classification of severity of SS.

Clinical question 17

17.1. What are the complications that can affect prognosis of SS?

17.2. Recommendation: Malignant lymphoma has been considered a serious complication that can affect the prognosis of SS. Furthermore, other hematological malignancies, such as multiple myeloma, as well as primary biliary cirrhosis, autoimmune hepatitis and pulmonary arterial hypertension have also been considered to affect the prognosis (Strength of recommendation; Weak).

17.3. Summary of evidence: The CPG committee systematically reviewed four cohort studies [Citation66–69] and one case–control study [Citation70]. The literature search did not find any large-scale study involving Japanese patients that discussed this topic. Summary analysis of these reports showed a mortality rate of approximately 1% for patients with lymphoproliferative disease (LPD) associated with primary SS (pSS), with little differences among the reports. Although no meta-analysis could not be performed due to the small number of suitable studies, the report from the National Cancer Center Japan (http://ganjoho.jp/reg_stat/statistics/stat/summary.html) showed cumulative mortality rate of pSS-related malignant lymphoma of 0.8% in men and 0.5% in women, suggesting a higher mortality rate in patients with pSS and malignant lymphoma than the general population. Although pulmonary arterial hypertension and amyloidosis were also considered complications that worsen prognosis, the number of large-scale studies was too small for a thorough systematic review. Based on these results, it is suggested that the development of LPD in pSS patients can worsen prognosis, although the clinical evidence for this is weak.

17.4. Development of recommendation: Various complications are known to be associated with pSS, including hematological malignancies (e.g. malignant lymphoma and multiple myeloma), liver diseases (e.g. primary biliary cirrhosis and autoimmune hepatitis), and cardiovascular diseases (e.g. pulmonary arterial hypertension), which can negatively affect prognosis of patients with pSS. Among these, the literature review could only establish the importance of malignant lymphoma on prognosis. Since there is no information on the mortality rate of patients with malignant lymphoma in the general population and on patients with pSS free of malignant lymphoma, it was not possible to conduct proper meta-analysis. The score for the overall evidence strength for the malignancies is D.

Clinical question 18

18.1. What are the characteristic clinical features of malignant lymphoma associated with SS?

18.2. Recommendation: Malignant lymphoma associated with primary SS is characterized clinically by a high incidence rate of marginal zone lymphoma (MZL), including mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma and nodal marginal zone lymphoma (NMZL). These features should be noted at diagnosis (Strength of recommendation; Strong).

18.3. Summary of evidence: Six observational studies, including four cohort [Citation66,Citation71–73] and two case–control studies [Citation74,Citation75] were identified and subjected to systematic review. The two case–control studies reported that the incidence rate of MZL, which comprised mainly of MALT lymphoma and NMZL, was significantly higher in patients with primary SS (pSS) compared with controls, among several types of malignant lymphomas associated with pSS (Strength of evidence; A). In contrast, these two studies reported no significant increase in the incidence rate of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) in patients with pSS [Citation74,Citation75] (Strength of evidence; A). Based on these results and the available strong evidence, the committee adopted the significantly high incidence rate of MZL, including MALT lymphoma and NMZL, in patients with pSS, compared with the general population, among several types of malignant lymphomas.

18.4. Development of recommendation: As suggested in Clinical Question 17, malignant lymphoma is an important complication that has a negative impact on prognosis of patients with pSS. Since characterization of the tissue type in malignant lymphoma associated with pSS can facilitate diagnosis and treatment of this condition, it is important to raise this clinical question. Systematic review of the available literature indicated a significantly high incidence rate of MZL, including MALT lymphoma and NMZL, in patients with pSS, relative to the control, among all the malignant lymphomas associated with pSS, while that of DLBCL was not, in six observational studies (four cohort and two case–control studies) (Strength of evidence; A).

Clinical question 19

19.1. What are the risk factors for development of malignant lymphoma in SS?

19.2. Recommendation: Salivary gland swelling, purpura (palpable purpura or cutaneous vasculitis), low serum C3 and C4 levels have been found as significant risk factors for the development of malignant lymphoma in patients with SS (Strength of recommendation; Strong).

19.3. Summary of evidence: Systematic review targeted seven cohort studies [Citation67,Citation68,Citation76–80] and one case–control study [Citation81]. These studies reported the findings of salivary gland swelling, purpura (palpable purpura or cutaneous vasculitis), low serum C3 and C4 levels. In addition, meta-analysis of four of the above cohort studies [Citation67,Citation78–80] demonstrated that salivary gland swelling was mentioned in all the four publications, and that such finding had a significant negative impact on prognosis of patients with primary SS (pSS) [Citation67,Citation68,Citation78,Citation80]. Furthermore, all the three papers that evaluated purpura indicated that this complication is also a risk factor for the development of malignant lymphoma [Citation67,Citation68,Citation77]. Four [Citation67,Citation76,Citation78,Citation79] of the five papers [Citation67,Citation68,Citation76,Citation78,Citation79] that reported low serum C3 levels and five [Citation67,Citation68,Citation77–79] out of six papers [Citation67,Citation68,Citation76–79] that reported low serum C4 levels in pSS patients indicated that both these findings were associated with significant increased risk of malignant lymphoma. Although only four publications used proper statistical analysis, meta-analysis of these risk factors showed they can impose significant increased risk. Based on these results and the strong evidence, it is suggested that salivary gland swelling (Strength of evidence; A), purpura (Strength of evidence; A), low serum C3 level (Strength of evidence; B) and low serum C4 level (Strength of evidence; B) are risk factors for the development of malignant lymphoma.

19.4. Development of recommendation: The CPG committee advocates of assessment of salivary gland swelling and purpura, as well as measurement of serum C3 and C4 levels in patients with SS as risk factors for the development of malignant lymphoma.

Clinical question 20

20.1. What are the main clinical features of glandular lesions in pediatric patients?

20.2. Recommendation: Recurrent parotid swelling is considered to improve the diagnostic sensitivity of pediatric patients. The presence of subjective and objective dry symptoms of the oral cavity or eyes is considered to be indicative of pediatric patients (Strength of recommendation; Strong).

20.3. Summary of evidence: Systematic review targeted six observational studies, including one prospective [Citation82] and five retrospective [Citation83–87] cohort studies. The I/C of Clinical Question 20 included ‘recurrent parotid swelling’, ‘increased dental caries’, ‘halitosis’, and ‘dry eyes’. The literature search did not identify cohort studies on ‘increased dental caries’ and ‘halitosis’ in pediatric patients. On the other hand, only three studies were published on ‘dry eyes’ as a subjective finding [Citation83,Citation84,Citation86]. Since these were retrospective cohort studies, which combined, included 23 cases only, the committee instead investigated the subjective and objective symptoms of oral cavity and eyes. The sensitivity of ‘recurrent parotid swelling’ for the diagnosis of glandular lesions ranged from 14% to 72% in these cohort studies, and 59% when data of the 81 cases included in the above cohort studies were summarized (Strength of evidence; C). The sensitivity of ‘dry oral cavity or eyes’ was 29–88% in these cohort studies, and 49% when summarized for the 81 cases (Strength of evidence; C). No control cases were included, and the specificity was not provided. The clinical presentation in pediatric patients often includes only few symptoms of dry oral cavity and eyes, compared with adult SS, and the results of the above studies were in agreement with this finding. While some cases included in the above cohort studies did not meet the AECG classification criteria (2002), they met the criteria after replacing ‘salivary gland lesion’ with ‘recurrent parotid swelling’. ‘Recurrent parotid swelling’ seemed to improve the sensitivity of diagnosis of pediatric patients.

20.4. Development of recommendation: The results of systematic review showed that ‘recurrent parotid swelling’ is a clinical finding in 60% of cases of pediatric patients. Therefore, recognition of glandular lesions as the objective symptoms is important for accurate diagnosis, since dry symptoms are not common in pediatric patients.

Clinical question 21

21.1. What are the clinical manifestations of extra-glandular lesions in pediatric patients with SS?

21.2. Recommendation: Articular symptoms, skin rash, fatigue, Raynaud’s phenomenon, fever, and lymphadenopathy are considered common symptoms of extra-glandular involvement in pediatric patients with SS. On the other hand, neurological symptoms, hepatitis, renal tubular acidosis (RTA), and peptic ulceration are considered uncommon but important complications (Strength of recommendation; Strong).

21.3. Summary of evidence: Systematic review included five observational studies (one prospective [Citation82] and four retrospective [Citation83–85] cohort studies). Analysis of data of all 70 cases of these publications showed the following sensitivities for the listed symptoms and signs in the diagnosis of pediatric SS: articular symptoms (31%), rash (27%), Raynaud’s phenomenon (17%), fatigue (17%), persistent fever (11%), lymphadenopathy (10%), neurological symptoms (10%), RTA (7%), hepatitis (9%), and gastrointestinal symptoms (7%) (Strength of evidence; C). The sensitivity of articular symptoms, rash, Raynaud’s phenomenon, fatigue, fever, lymphadenopathy, and neurological symptoms varied widely in the above cohort studies. The specificity of each symptom could not be analyzed due to the lack of control subjects. The sensitivity of even the articular symptom, which was the most frequent symptom in extra-glandular involvement, was lower (31%) than that of recurrent swelling of the parotid gland (59%), which was recommended in Clinical Question-20 above, as the symptom diagnostic for glandular involvement in SS, though it improved the diagnosis in pediatric patients.

21.4. Development of recommendation: Systematic review of the literature indicated that articular symptoms, skin rash, fatigue, Raynaud’s phenomenon, fever, and lymphadenopathy are extra-glandular involvement in pediatric SS patients. Neurological symptoms, hepatitis, RTA, and peptic ulceration often require treatment. In pediatric SS patients, oral cavity and eye dryness is not common. Thus, these extra-glandular involvements, which sometimes could be difficult to treat, are important complications for diagnosis and target of treatment in pediatric patients with SS.

Clinical question 22

22.1. Which hematological findings are useful for the diagnosis of SS in pediatric patients?

22.2. Recommendation: It has been considered that positive ANA and anti SS-A/Ro antibodies have high sensitivities for the diagnosis of SS in pediatric patients. Rheumatoid factor, hypergammaglobulinemia, and anti-SS-B/La antibody have also been considered useful (Strength of recommendation; Strong).

22.3. Summary of evidence: Eight observational studies [Citation56,Citation82,Citation84–89] were found and submitted for systematic review. The analysis showed a positive rate of ANA of 84% (62–100%) (Strength of evidence; D), while that of anti SS-A/Ro antibody was 72% (36–100%) (Strength of evidence; D). Analysis of seven of these studies [Citation56,Citation82,Citation85–89] showed a positive rate of rheumatoid factor (RF) of 68% (27–100%). On the other hand, analysis of another set of seven studies [Citation56,Citation82,Citation84,Citation85,Citation87–89] showed a positive rate of hypergammaglobulinemia of 52% (18–100%) (Strength of evidence; D). Analysis of seven studies [Citation56,Citation84–89] showed a positive rate of anti SS-B/La antibody of 36.2% (0–100%) (Strength of evidence; D), while analysis of two studies [Citation82,Citation83] showed a positive rate of high salivary amylase of 46% (range, 39–100%) (Strength of evidence; D). The literature found no studies that dealt with the hematological findings associated with the severity of the disease in pediatric SS patients.

22.4. Development of recommendation: For this clinical question, the committee assessed ANA, anti SS-A/Ro antibody, anti SS-B/La antibody, RF, hypergammaglobulinemia, and salivary amylase. Analysis of eight observational studies [Citation56,Citation82,Citation84–89] showed no diagnostic specificity for any of the hematological findings. In pediatric patients, dryness is not common. However, the hematological findings are similar to those of adult patients.

Clinical question 23

23.1. Which tests are useful for the diagnosis of glandular lesions in pediatric patients?

23.2. Recommendation: (1) Sialography (including MR sialography) and labial salivary gland biopsy have been recommended for the diagnosis of glandular lesions of pediatric patients; both have high sensitivity (Strength of recommendation; Strong). (2) Salivary scintigraphy, Schirmer test, and keratoconjunctive staining test have been recommended for the diagnosis of glandular lesions (Strength of recommendation; Weak).

23.3. Summary of evidence: Five observational studies [Citation56,Citation82–84,Citation89] and one cross-sectional case study [Citation87] were available for systematic review. In four of the observational studies [Citation56,Citation81–83], the sensitivity of Schirmer test in pediatric patients with pSS was 14–69%. The literature search found no studies that assessed the Rose Bengal test alone. In one study, 73% of the patients satisfied both the Rose Bengal and Schirmer test, and 83% satisfied one of them (Strength of evidence; D). In two observational studies [Citation82,Citation83], the sensitivity of salivary sialography was 91–100% in pediatric patients with pSS (Strength of evidence; D). Another study reported a strong correlation between the results of MR sialography and X-ray sialography [Citation56] (Strength of evidence; D). The reported sensitivity of the salivary secretion test was 82% in [Citation87], and that of salivary scintigraphy 75% [Citation82] (Strength of evidence; D). In another observational study, 71% of the patients showed some abnormalities on sialography, salivary scintigraphy and saliva secretion [Citation83] (Strength of evidence; D). In five observational studies, the sensitivity of labial salivary biopsy for the diagnosis of pediatric patients with pSS ranged from 62% to 100% [Citation56,Citation82–84,Citation87]. In one out of five cross-sectional studies, which included a control groups, the sensitivity and specificity of labial salivary biopsy were 67% and 100%, respectively. No studies were identified that examined the sensitivity of clinical examination for the assessment of severity of pediatric patients with pSS. Furthermore, there were no studies on the adverse events. Based on the above results, sialography and labial salivary gland biopsy have high sensitivity for the diagnosis of glandular lesions in pediatric patients with pSS.

23.4. Development of recommendation: Salivary sialography and labial salivary gland biopsy were performed in many cases of pediatric patients with pSS, with high sensitivity. On the other hand, fewer studies of small sample numbers assessed the values of salivary scintigraphy, Schirmer test, and Rose Bengal staining. Accordingly, the committee does not strongly recommend their use for the diagnosis of glandular lesions in pediatric patients with pSS. However, positive results may provide useful information since these tests are included in diagnostic and classification criteria.

Clinical question 24

24.1. What is the recommended treatment for dry mouth?

24.2. Recommendation: Cevimeline hydrochloride and pilocarpine hydrochloride have been recommended for the treatment of dry mouth as they can improve salivary secretion and dry mouth (Strength of recommendation; Strong).

24.3. Summary of evidence:

24.3.1. Cevimeline hydrochloride: Systematic review of three RCTs [Citation90–92] showed significant increases in the average and rate of change of salivary flow rate after treatment, compared with placebo, in two of these RCTs [Citation90,Citation92], while one RCT [Citation91] showed no significant difference among before/after cevimeline and placebo (Strength of evidence; B). Based on meta-analysis of the two RCTs [Citation90,Citation92], cevimeline significantly improved dry mouth compared with placebo. In all three RCTs [Citation90–92], cevimeline significantly improved medical interview scores related to dry mouth, compared with placebo (Strength of evidence; A). One RCT [Citation92] showed significant improvement of tongue appearance following cevimeline, compared with placebo (Strength of evidence; C). Evaluation of oral mucosal abnormalities was not provides in these studies [Citation90,Citation92]. Meta-analysis of the three RCTs [Citation90–92] showed that the use of cevimeline is associated with various side effects (nausea, excessive sweating, chills, and palpitations) compared with placebo, but the difference did not reach the statistical significance (Strength of evidence; B).

24.3.2. Pilocarpine hydrochloride: Systematic review of three RCTs [Citation93–95] showed significant increase in salivary flow rate after treatment with pilocarpine (Strength of evidence; B). Furthermore, pilocarpine significantly improved dry mouth and medical interview scores related to dry mouth compared with placebo (Strength of evidence; A). Evaluation of oral mucosal abnormalities was not recorded in these studies [Citation93–95] (Strength of evidence; D). Three RCTs reported no serious adverse events [Citation93–95]. In two of the RCTs [Citation94,Citation95], pilocarpine induced significant pollakisurea and sweating, compared with placebo (Strength of evidence; C).

24.3.3. Herbal medicine: Systematic review of two RCTs [Citation96,Citation97] showed significant increase in salivary flow rate after treatment with dwarf lilyturf decoction [Jp: bakumondoto], but not in the control group (placebo, qi-benefiting decoction [Jp: hochuekkito]). One RCT [Citation96] showed increase in salivary secretion in 77% of the patients by dwarf lilyturf decoction (Strength of evidence; C). In one RCT [Citation97], dwarf lilyturf decoction significantly improved medical interview scores related to dry mouth and appearance of tongue, compared with the placebo (Strength of evidence; D). One RCT [Citation96] showed no serious side effects (Strength of evidence; D).

24.3.4. Oral moisturizing agents: Two RCTs [Citation88,Citation98] and five cohort studies [Citation99–103] were systematically reviewed. One RCT [Citation104] and two cohort studies [Citation99,Citation102] showed no significant improvement of salivary secretion after the use of oral moisturizing agents, compared with placebo (Strength of evidence; D). One cohort study [Citation103] showed increased salivary secretion following the use of Azunol ointment, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (Strength of evidence; D). One RCT [Citation104] showed improvement in dry mouth following the use of oral moisturizing gel, compared with placebo, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (Strength of evidence; D). Four cohort studies [Citation99–102] showed significant improvement in dry mouth symptoms following the use of oral moisturizing agents (Strength of evidence; D). One cohort study [Citation103] showed no improvement in dry mouth by Azunol ointment (though a significant improvement in tongue pain was reported) (Strength of evidence; D). Neither of the two RCTs [Citation105,Citation106] recorded evaluations of oral mucosal abnormalities (Strength of evidence; D). Two cohort studies [Citation100,Citation102] showed significant improvement in oral mucosal abnormalities following oral moisturizing agents, while one cohort study [Citation103] showed no significant improvement with Azunol ointment (Strength of evidence; D). One RCT [Citation104] and one cohort study [Citation102] showed no side effects (Strength of evidence; D). In the other RCT [Citation98], one patient stopped the use of oral balance gel following sensation of abdominal fullness (Strength of evidence; D). Two cohort studies [Citation99,Citation100] reported the development of nausea, unpleasant taste, oral discomfort, loose stools, and stomach discomfort after the use of oral balance gel (Strength of evidence; D).

24.4. Development of recommendation: The CPG committee recommends the use of cevimeline to improve salivary secretion (by moderate evidence), dry mouth (by strong evidence), and oral mucosal abnormalities (by weak evidence). However, cevimeline can induce adverse events (by moderate evidence). On the other hand, the use of pilocarpine can improve salivary secretion (by moderate evidence), and dry mouth (by strong evidence). Oral mucosal abnormalities (by weak evidence) could not be evaluated. However, cevimeline induced pollakisurea and sweating (by weak evidence). Herbal medicine can improve salivary secretion (by weak evidence), dry mouth, and oral mucosal abnormalities (by very weak evidence). Furthermore, herbal medicine has almost no side effects (by very weak evidence). Oral moisturizing agents can improve dry mouth and oral mucosal abnormalities (by very weak evidence), and have virtually no side effects (by very weak evidence). However, oral moisturizing gel and artificial saliva have adverse events related to digestive symptoms (by very weak evidence).

Clinical question 25

25.1. What is the recommended treatment of salivary gland swelling?

25.2. Recommendation: Antimicrobial agents and corticosteroids have been considered to improve recurrent swelling of the salivary glands. Parotid gland irrigation has been found to improve swelling and prevent recurrence (Strength of recommendation; Weak).

25.3. Summary of evidence:

25.3.1. Antimicrobial agents: Two case reports [Citation99,Citation100] were systematically reviewed. One case report [Citation99] showed improvement in salivary gland swelling after administration of antimicrobial agents, while the other study [Citation100] indicated that prophylactic use of antimicrobial agents prevented recurrence (Strength of evidence; D). Neither of the two case reports [Citation99,Citation100] evaluated salivary flow rate or evaluated adverse events (Strength of evidence; D).

25.3.2. Corticosteroids: Six case reports [Citation101–103,Citation107–109] were systematically reviewed. Six of these [Citation101–103,Citation107–109] reported improvement in salivary gland swelling and prevention of recurrence by corticosteroid (Strength of evidence; D). However, the dose used and tapering rate of corticosteroid were different in each case report. In some of these reports, methotrexate and hydroxyapatite chloroquine were combined with corticosteroids. None of the six case reports [Citation101–103,Citation107–109] evaluated salivary secretion or side effects (Strength of evidence; D).

25.3.3. Parotid gland irrigation: Systematic review of four cohort studies was conducted [Citation105,Citation106,Citation110,Citation111]. One cohort study [Citation105] showed improvement in salivary gland swelling after salivary endoscopic irrigation, combined with dilation and steroid injections. Another cohort study [Citation106] reported prevention of recurrence following these treatments (Strength of evidence; D). Two cohort studies [Citation110,Citation111] showed significant increases in salivary secretion after corticosteroid irrigation of the parotid glands (Strength of evidence; D). However, it was not clear from these studies whether the patients suffered from recurrent swelling of the salivary glands. In three cohort studies [Citation105,Citation110,Citation111], there was no report of adverse events associated with parotid gland irrigation (Strength of evidence; D).

25.3.4. Prevention by promotion of saliva secretion: The literature search did not find any study on prevention of salivary gland swelling following promotion of salivary secretion.

25.4. Development of recommendation: The CPG committee suggests that antimicrobial agents and corticosteroid can improve recurrent swelling of salivary glands (by very weak evidence), but the committee could not make strong recommendation on the use of these medication to improve salivary secretion and reduce adverse events due to paucity of information in the literature. Salivary gland (parotid gland) irrigation can improve recurrent swelling and salivary secretion (by very weak evidence), and is associated with minimal number of adverse events (by very weak evidence).

Clinical question 26

26.1. Can the use of rebamipide, diquafosol sodium and sodium hyaluronate ophthalmic solutions improve corneal conjunctival epithelial disorders, tear fluid volume, and subjective symptoms of dry eye?

26.2. Recommendation: (1) Rebamipide ophthalmic solution has been considered a treatment option as it improves corneal conjunctival epithelial disorder and dry eye (Strength of recommendation; Strong). (2) Diquafosol sodium ophthalmic solution has been considered a treatment option since it improves corneal conjunctival epithelial disorder and dry eye and tends to improve tear fluid volume (Strength of recommendation; Strong). (3) Sodium hyaluronate ophthalmic solution has been considered a treatment option as it improves corneal conjunctival epithelial disorder and dry eye (Strength of recommendation; Strong).

26.3. Summary of evidence:

26.3.1. Rebamipide ophthalmic solution: Systematic review of one RCT [Citation112] on rebamipide ophthalmic solution was conducted, which showed improvement in corneal and conjunctival epithelial disorder and dry eye symptoms (Strength of evidence; C).

26.3.2. Diquafosol sodium ophthalmic solution: Two observational studies (two prospective cohort studies) [Citation113,Citation114] assessed diquafosol sodium ophthalmic solution and were systematically reviewed. Both reported that diquafosol sodium ophthalmic solution could improve corneal and conjunctival epithelial disorder and dry eye symptoms, tended to improve tear fluid volume and had no side effects (Strength of evidence; C).

26.3.3. Sodium hyaluronate ophthalmic solution: Systematic review of one RCT on sodium hyaluronate ophthalmic solution [Citation115] showed that this ophthalmic solution could improve corneal and conjunctival epithelial disorder and dry eye symptoms and had no serious side effects (Strength of evidence; C).

26.4. Development of recommendation: The three ophthalmic solutions of rebamipide, diquafosol sodium and sodium hyaluronate are recommended for treatment of corneal conjunctival epithelial disorders and dry eye symptoms, based on the findings of one RCT, two observational studies and one RCT, respectively, as well as the lack of serious adverse events (Strength of evidence; C).

Clinical question 27

27.1. Does the use of punctal plug improve tear fluid volume, corneal conjunctival epithelial disorder and subjective symptoms in dry eye?

27.2. Recommendation: Punctal plug has been considered a treatment option to improve tear fluid volume, corneal epithelial disorder and dry eye (Strength of recommendation; Strong).

27.3. Summary of evidence: Systematic review of one RCT [Citation116] showed that punctal plug could clearly improve tear fluid volume compared with artificial tears (Strength of evidence; C). However, it also showed increased tear fluid volume in the instillation group. The same treatment also improved corneal epithelial disorder and dry eye symptoms (Strength of evidence; C), but its effect on conjunctival epithelial disorders was not clarified (Strength of evidence; D) and side effects were not reported (Strength of evidence; D). Based on these results, it is recommended that punctal plug is effective for improvement of tear fluid volume, corneal epithelial disorder and dry eye symptoms, while the effect on conjunctival epithelial disorders and adverse events remain unknown.

27.4. Development of recommendation: Systematic review of one RCT indicated that punctal plug can improve tear fluid volume, corneal epithelial disorder and dry eye symptoms (Strength of evidence; C). No data are available on the use of punctal plug in conjunctival epithelial disorders and side effects. The CPG committee advocates the use of punctal plug. However, there is limited information on the use of punctal plugs in difficult cases with regard to the placement of plug. The committee decided not to recommend a specific time for the placement of the plug because early placement is needed in some patients with severe dryness.

Clinical question 28

28.1. Is corticosteroid effective treatment for glandular lesions?

28.2. Recommendation: It is considered that systemic administration of corticosteroid cannot improve salivary and lacrimal secretion (Strength of recommendation; Weak).

28.3. Summary of evidence: The committee systematically reviewed one RCT [Citation117] and four observational studies (two prospective [Citation15,Citation118] and two retrospective [Citation119,Citation120] cohort studies). The RCT [Citation117] concluded that corticosteroid did not improve salivary and lacrimal secretion, compared with placebo (Strength of evidence; C). Although meta-analysis of the two retrospective cohort studies [Citation119,Citation121] showed increased salivary secretion in response to corticosteroid therapy, compared with the control treatment, the difference was not statistically significant (Strength of evidence; D). Although one retrospective cohort study [Citation5] showed corticosteroid therapy increased lacrimal secretion, compared with the control, the difference between groups did not reach statistical significance (Strength of evidence; D). One RCT [Citation117] concluded that corticosteroid significantly improved dry mouth, compared with placebo (Strength of evidence; C). Although one retrospective cohort study [Citation121] showed improvement of dry mouth by corticosteroid compared with the control, the difference was not statistically significant (Strength of evidence; D). One retrospective cohort study [Citation121] concluded that corticosteroid therapy could be complication with infections (Strength of evidence; D). In conclusion, we have demonstrated in the present study, there is weak evidence for improvement of dry mouth by systemic corticosteroid, but the latter had no effect on salivary and lacrimal secretion, and might induce infections.

28.4. Development of recommendation: Review of the available literature indicated that systemic administration of corticosteroid could improve dry mouth but not salivary and lacrimal secretion in the small RCT (Strength of evidence; C). No definite evidence is available to date about the risk and benefits of corticosteroids. Based on the above review, the CPG committee recommendation falls within the lines of these findings. The committee is aware that several other questions need to be answered such as the relationship between disease stage/severity and efficacy of corticosteroid for glandular involvement, and potential risks of corticosteroid use other than infections.

Clinical question 29

29.1. Is the use of corticosteroids treatment efficacious for extra-glandular lesions in SS?

29.2. Recommendation: It has been suggested that systemic administration of corticosteroid can improve articular, muscle, and skin involvements in SS (Strength of recommendation; Weak).

29.3. Summary of evidence: Four observational cohort studies were systematically reviewed [Citation120,Citation122–124]. One cohort study [Citation124] showed improvement of lung involvement by systemic administration of corticosteroid without comparison with control (Strength of evidence; D). Another cohort study [Citation122] demonstrated a tendency for improvement of renal involvement following systemic administration of corticosteroid but the results were not significant (Strength of evidence; D). Improvement of central nerve involvement in response to systemic corticosteroid (though without comparison with control) was also reported in another cohort study [Citation120] (Strength of evidence; D). The fourth cohort study [Citation123] reported significant improvement of articular, muscle, and skin involvements following systemic corticosteroid therapy (Strength of evidence; D). None of these or other studies provided data on ESSDAI, ESSPRI, cytopenia, hypergammaglobulinemia, peripheral neural systems, or infections as an adverse effect (Strength of evidence; D).

29.4. Development of recommendation: Review of the available literature indicated that systemic administration of corticosteroid can improve articular, muscle, and skin involvements (Strength of evidence; D). More analysis is needed, however; to evaluate the effects of such treatment on other extra-glandular involvements.

Clinical question 30

30.1. Are immunosuppressants effective against glandular lesions in SS?

30.2. Recommendation: It has been recommended that mizoribine can increase salivary secretion and improve dryness. Methotrexate is also considered efficacious for dryness symptoms (Strength of recommendation; Weak).