Abstract

Objectives: To evaluate the real-world safety and effectiveness of etanercept (ETN) in Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Methods: This postmarketing surveillance study (NCT00503139) assessed the safety and effectiveness of ETN treatment over 3 and 2 years (from June 2007 to September 2011), respectively. Safety was evaluated by occurrence and seriousness of adverse drug reactions (ADRs), and of adverse events (AEs) for malignancies. Effectiveness was assessed using the Disease Activity Score in 28 joints based on the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) with four variables (swollen and tender joint counts, ESR, and patient global assessment; DAS28-4/ESR). Treatment was considered effective if patients had a good/moderate response by the European League Against Rheumatism response criteria.

Results: ADRs occurred in 256/675 (37.9%) patients, the most common being injection site reactions (4.4%) and nasopharyngitis (3.3%). Serious ADRs occurred in 60/675 (8.9%) patients, the most frequent being pneumonia (1.2%). The incident rate of malignancies (AEs) was 1.06 per 100 patient-years. Mean baseline DAS28-4/ESR for the 581 patients included in effectiveness analysis was 5.42, which decreased to 3.32 at 2 years. Eighty-two percent of patients achieved a moderate/good response at 2 years.

Conclusion: Long-term ETN treatment safety and effectiveness were sustained over 3 and 2 years, respectively.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic autoimmune disease involving the progressive destruction of the joints that significantly causes pain and functional disability [Citation1]. The prevalence of RA is 0.2% globally [Citation2], and between 0.6% and 1.0% in Japan [Citation3]. Management of RA involves the use of conventional synthetic disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs), such as methotrexate (MTX), as first-line therapy [Citation4,Citation5]. In patients failing to respond to csDMARDs, current recommendations suggest the use of csDMARDs combined with biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs), such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors [Citation4,Citation5]. The efficacy and safety of TNF inhibitors in patients with RA have been demonstrated in several randomized clinical trials [Citation6–13]. However, rare safety issues associated with the treatment may not arise in the controlled conditions of clinical trials due to the strict study inclusion and exclusion criteria. Observational studies, with no strict inclusion/exclusion criteria and with a high number of patients, including those with multiple comorbidities [Citation14], provide essential information for clinical practice, because they reflect real-life scenarios [Citation15]. Postmarketing surveillance (PMS) is a method to monitor and assess real-world effectiveness and safety of a drug following its market release. The long-term nature of these surveillance studies allow the assessment of health risks associated with the use of a medicinal drug over time.

In RA clinical trials with TNF inhibitors, Japanese patients had higher responses than Western patients treated with the same TNF inhibitors [Citation16–18], suggesting that Japanese patients with RA may have a unique genetic and environmental background that influences the effectiveness and safety of these agents [Citation19]. Etanercept (Enbrel®; ETN; Wyeth, Tokyo, Japan; Pfizer and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, Osaka, Japan) is a TNF inhibitor used to treat patients with RA who have had an inadequate response to at least one csDMARD. ETN has been marketed in Japan since the end of March 2005 [Citation20], following conditional approval by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) that required both an All Cases Surveillance program and a long-term PMS to confirm the safety and effectiveness of ETN treatment. The All Cases Surveillance program has previously demonstrated the safety and effectiveness of ETN treatment over 6 months in ∼14,000 Japanese patients with RA [Citation21].

In this independent and nationwide PMS study, we evaluated the long-term safety of ETN, including incidence of malignancies, in Japanese patients with RA over a period of 3 years and effectiveness over 2 years.

Materials and methods

Study design and patients

This study (NCT00503139) was conducted in Japan between June 2007 and September 2011 (registration period from June 2007 to September 2008) after the completion of the All Cases Surveillance program. Data were obtained from 87 registered Japanese sites (16 national, public, or private university hospitals [133 patients]; 8 national hospitals [72 patients]; 9 public hospitals [63 patients]; 5 public institutions [39 patients]; 18 any other hospital [152 patients]; 31 clinics or doctors’ offices [225 patients]), and patient information was obtained from case report forms using electronic data capture. Patients with RA who had an inadequate response to csDMARDs, who were never treated with ETN, who had neither history nor concurrency of malignancies were enrolled in this study. The protocol for this PMS was reviewed and approved by the MHLW and the study was conducted in accordance with good postmarketing surveillance practice.

Endpoints

The primary endpoints assessed were safety and effectiveness of ETN treatment in Japanese patients with RA over 3 and 2 years, respectively. Safety data were coded with preferred terms according to system organ class from the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA/J ver.15.0). Effectiveness of treatment was assessed using the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) response criteria as measured by level of and change in the Disease Activity Score in 28 joints (DAS28) based on the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) with four variables (swollen and tender joint count, ESR and patient global assessment; DAS28-4/ESR) [Citation22]. Secondary effectiveness endpoints included change in DAS28-4/ESR and DAS28-3/ESR calculated using three variables (swollen and tender joint count and ESR), change in DAS28 based on C-reactive protein (CRP) calculated using four (swollen and tender joint count, CRP and patient global assessment; DAS28-4/CRP) or three variables (swollen and tender joint count and CRP; DAS28-3/CRP), the modified Health Assessment Questionnaire (mHAQ) score (eight question assessment) [Citation23], and the Visual Analog Scale to evaluate fatigue severity (VAS fatigue; 100-mm scale) [Citation24].

Data analysis

The proportion of patients experiencing adverse drug reactions (ADRs), serious ADRs (SADRs), and infections were reported. Malignancies were evaluated as both ADRs and adverse events (AEs). Incidence rates (IR) were calculated as the number of patients with serious infection and infestations, herpes zoster, and malignancy on first occurrence as AE per 100 patient-years. Kaplan–Meier plots were generated to show occurrence rates of ADRs. Factors affecting safety were studied using a Cox proportional hazard model, whereas factors affecting effectiveness were studied using the χ2 test, the Cochran–Armitage (CA) trend test, and logistic regression analysis. For the effectiveness analysis, one-sample t-test was used to compare each item before and after treatment, and the McNemar test was used to assess improvement in DAS28-4/ESR response. The statistical test was two-tailed at a significance level of p < .05. Missing data were imputed using the last observation carried forward (LOCF) method, except baseline values for DAS28-4/ESR, DAS28-3/ESR, DAS28-4/CRP, DAS28-3/CRP, mHAQ score, and VAS fatigue, which were not carried forward. Patients who dropped out or discontinued were eligible for inclusion in the effectiveness analysis. DAS28 was divided into four categories: remission (<2.6), low disease activity (≥2.6 and <3.2), moderate disease activity (≥3.2 and ≤5.1), and high disease activity (>5.1). Good response was defined as DAS28 improvement from baseline of >1.2 and a DAS28 score obtained during follow-up of <3.2. Non-responders were patients with DAS28 improvement of <0.6, or patients with DAS28 improvement from baseline between 0.6 and 1.2 and with a DAS28 score during follow-up of >5.1. The remaining patients were classified as moderate responders.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 675 and 582 patients were included in the safety and effectiveness analysis, respectively. For the effectiveness analysis, data either before or after drug administration were missing from 93 patients. The initial ETN dose was 25 mg twice a week in 83.6% of patients and 25 mg once a week in 16.1%. In two patients, the dosing pattern was a 15 mg dose once every 2 weeks and a 25 mg dose five times every 3 weeks.

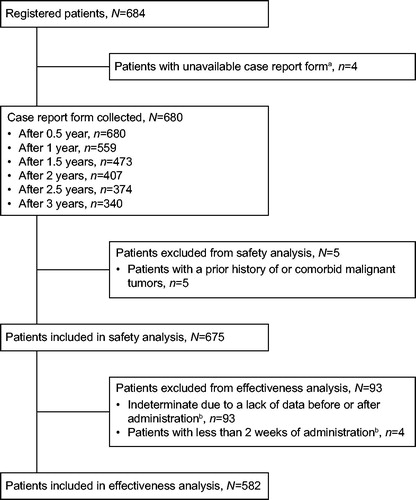

A total of 684 patients were registered in the study; the case report form was not available for four of them and they were excluded from the analysis (). Of the 680 remaining patients, five were excluded as having history of or concomitant malignant tumors (). Baseline characteristics of the 675 patients included in the safety analyses are shown in . The majority of patients were female (82.7%); the mean (SD) duration of disease was 8.4 (6.6) years (RA duration ≥10 years in 38.1% of patients). Sixty-one percent of patients were in either Steinbrocker stage III or IV, and 23.1% were in either Steinbrocker functional class 3 or 4. The mean (SD) DAS28-4/ESR before starting drug administration was 5.42 (1.26). At baseline, 60.4% of patients received concomitant MTX (mean [SD] dose of 7.0 [2.1] mg) and 73.8% of patients received concomitant corticosteroids. Nearly all patients (97.5%) received a chest X-ray or computed tomography scan, and 89.5% of patients received a tuberculin skin test.

Figure 1. Patient disposition. aReasons for unavailability are: tightening of regulations for facility visits (n = 2), patient was found to be ineligible (n = 1), patient was referred to another facility (n = 1). bFour patients of ‘Indeterminate due to a lack of data before or after administration’ also fall under ‘Patients with less than 2 weeks of administration’.

Table 1. Demographic and baseline characteristics of patients participating in the safety analysis.

Safety analysis

Over the 3-year period of the surveillance, 37.9% (256/675) of patients developed ADRs (). Injection site reaction was the most commonly observed ADR (4.4%) followed by nasopharyngitis (3.3%), bronchitis (3.0%), and upper respiratory tract inflammation (3.0%). Infections and infestations were reported in 106/675 patients (15.7%). Over the surveillance study, 60/675 patients (8.9%) developed SADRs (); the most common being pneumonia (1.2%) followed by interstitial lung disease (0.9%), bronchitis, herpes zoster, breast cancer, and gastric cancer (0.4% each). Thirty (4.4%, ADRs) and 32 (4.7%, AEs) patients developed serious infections and infestations over the study period, corresponding to an IR of 2.47 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.69–3.48)/100 patient-years. Tuberculosis (TB) was observed in two patients with one event each at between 0.5 and 1 year (pulmonary TB) and between 1 and 2 years (disseminated TB). Thirteen events of herpes zoster in 13 patients were reported as ADRs; of these, three were reported as SADRs. Fourteen events of herpes zoster in 14 patients were reported as AEs, corresponding to an IR of 1.07 (95% CI, 0.59–1.80)/100 patient-years.

Table 2. Proportion of adverse drug reactions (occurring in ≥10 patients [≥1.5%]) and serious adverse drug reactions (occurring in ≥3 patients [≥0.4%]).

A total of 15 events of malignancies (AEs) in 14 patients were reported during the surveillance period (), corresponding to an IR of 1.06 (95% CI, 0.58–1.78)/100 patient-years. There was no clear trend in the time of onset of malignant tumors. One 79-year-old female patient with a previous history of interstitial lung disease developed concurrent gastric cancer and lung neoplasm malignant. The administration of ETN was discontinued but the outcome for both conditions was unrecovered/unchanged. The cause of these malignant events could not be determined. Five deaths were reported during the study, two of which (one each of metabolic acidosis and interstitial lung disease) were deemed to be potentially treatment-related. The other three deaths were sudden cardiac death, cerebral hemorrhage, and sudden death. All ADRs and SADRs reported during the 3-year surveillance period are shown in Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Table S2, respectively.

Table 3. Timing of occurrence of malignancies (adverse events).

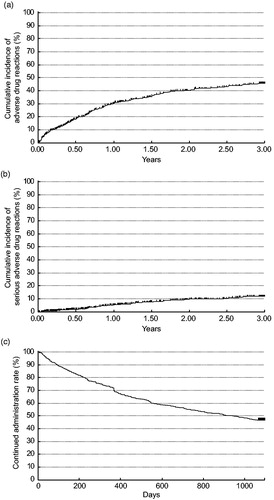

Of the patients who developed ADRs over the study period, 27.3% (184/675) were reported within 1 year, 18.9% (90/475 patients) between 1 and 2 years, and 11.6% (43/372) between 2 and 3 years. SADRs occurred in 4.3% (29/675) of patients within 1 year, 5.1% (24/475) between 1 and 2 years, and 3.5% (13/372) between 2 and 3 years. The cumulative incidence of ADRs and SADRs are shown in . In terms of average dose per week, ADRs occurred in no patients (0/11) at <20 mg ETN dose, 33.3% (3/9) of patients at ≥20 mg to <25 mg ETN dose, 42.1% (32/76) of patients at 25 mg ETN dose, 52.1% (88/169) of patients at >25 to <50 mg ETN dose, and 32.4% (133/410) of patients at 50 mg ETN dose. The proportion of ADRs was not dose dependent (data not shown).

Figure 2. Kaplan–Meier plot of (a) adverse drug reactions, (b) serious adverse drug reactions, (c) continued administration. Discontinuations are shown as thin vertical lines.

Several demographic and baseline characteristics were found to be significantly associated with the risk of ADRs, SADRs, infections, and serious infections as shown in . Concomitant use of MTX was a significant factor that decreased the risk ratio for the incidence of ADRs and serious infections. Increased age was a significant factor that increased the risk of SADRs and serious infections.

Table 4. Hazard ratios for adverse drug reactions, serious adverse drug reactions, infectious disease, and serious infectious disease by Cox proportional hazard model.

Treatment duration and reasons for treatment discontinuation

Among the patients included in the safety population, 53.5% (361/675) of patients dropped out or were discontinued. The mean time period from administration to discontinuation was 382.8 days (). The most common reason for discontinuation was lack of effectiveness, which occurred in 13.3% of patients (90/675), followed by AEs and hospital transfer in 12.4% (84/675) and 9.0% (61/675) of patients, respectively.

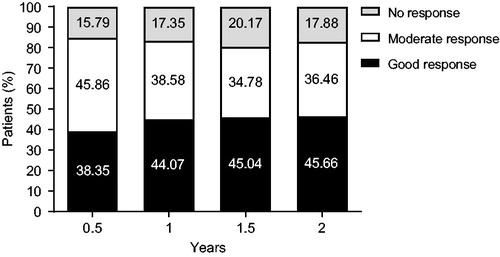

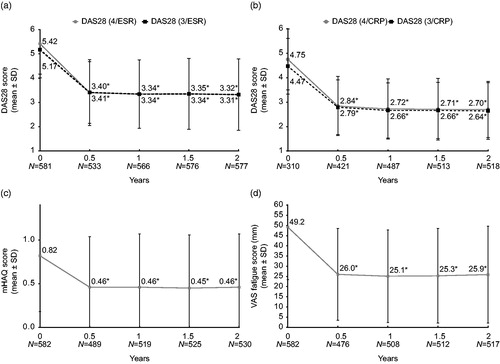

Effectiveness analysis

Effectiveness of ETN was evaluated for up to 2 years after administration in 582 patients. The proportion of patients with a good/moderate response as measured by DAS28-4/ESR change was 84.21% (95% CI, 80.83–87.21%), 82.65% (95% CI, 79.28–85.69%), 79.83% (95% CI, 76.31–83.03%), and 82.12% (95% CI, 78.74–85.16%) after 0.5, 1, 1.5, and 2 years, respectively (). Secondary endpoints are shown in . DAS28-4/ESR and DAS28-3/ESR mean scores improvements were significant at every time point (p < .001). Similarly, significant improvements from baseline were observed in the mean DAS28 scores if based on CRP (three or four variables) at every time point (p < .001). The mean mHAQ scores decreased from 0.82 at baseline to 0.46 after 0.5 year, remaining constant at 0.45–0.46 after 1 year to after 2 years. Mean VAS fatigue scores improved from 49.2 mm at baseline to 26.0 mm after 0.5 year, and then remained constant at 25.1–25.9 mm after 1 year to after 2 years. Improvements in mHAQ and VAS fatigue scores from baseline were significant at every time point (p < .001).

Figure 3. Change in EULAR DAS28-4/ESR response over 2 years. DAS28: Disease Activity Score in 28 joints; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

Figure 4. Change in secondary endpoints over 2 years in (a) DAS28-4/ESR and DAS28-3/ESR; (b) DAS28-4/CRP and DAS28-3/CRP; (c) mHAQ score; (d) VAS fatigue score. * p < .001; CRP: C-reactive protein; DAS28: Disease Activity Score in 28 joints; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; mHAQ: modified Health Assessment Questionnaire; VAS: visual analog scale.

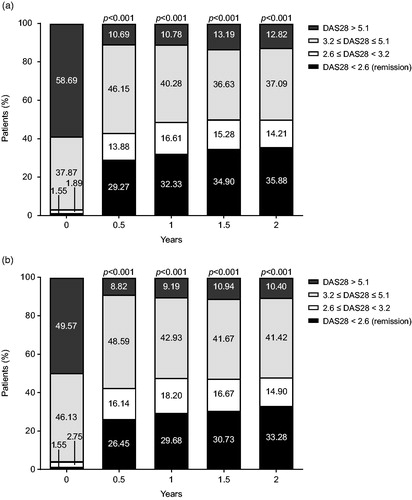

Changes in DAS28-4 or DAS28-3/ESR activity are shown in . Throughout the surveillance period, the proportion of patients in DAS28-4/ESR remission increased from 1.55% (9/581 patients) at baseline to 29.27% (156/533 patients), 32.33% (183/566 patients), 34.90% (201/576 patients), and 35.88% (207/577 patients) at 0.5, 1, 1.5, and 2 years, respectively (). The improvements observed at every time point compared to baseline were significant (p < .001). The remission rates for DAS28-3/ESR improved from 1.55% (9/581 patients) at baseline to 26.45% (141/533 patients), 29.68% (168/566 patients), 30.73% (177/576 patients), and 33.28% (192/577 patients) at 0.5, 1, 1.5, and 2 years, respectively (). The proportion of patients in mHAQ remission (defined as <0.5) increased (95% CI) from 35.22% (31.34–39.26%) at baseline to 65.44% (61.04–69.65%), 65.13% (60.85–69.23%), 65.90% (61.67–69.96%), and 65.09% (60.87–69.15%) after 0.5, 1, 1.5, and 2 years, respectively (data not shown).

Figure 5. Change in (a) DAS28-4/ESR and (b) DAS28-3/ESR activity over 2 years. DAS28: Disease Activity Score in 28 joints; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

For factors affecting effectiveness, a significant difference in the EULAR response was observed depending on DAS28-4/ESR activity at the start of administration (low/moderate versus high [test versus reference for all], full model odds ratio [OR]: 0.566; 95% CI, 0.358–0.894; p = .0146; variable selection OR: 0.611; 95% CI, 0.393–0.951; p = .0289), and disease duration (≥2 years to <5 years versus ≥10 years, full model OR: 0.569; 95% CI, 0.299–1.082; p = .0345). Sex (female versus male, full model OR: 0.602; 95% CI, 0.309–1.174), age (<65 years old versus ≥65 years old, full model OR: 1.280; 95% CI, 0.771–2.123), disease duration (<2 years versus ≥10 years, full model OR: 0.821; 95% CI, 0.399–1.690; ≥5 years to <10 years versus ≥10 years, full model OR: 1.279; 95% CI, 0.661–2.472), Steinbrocker stage (I + II versus III + IV, full model OR: 1.090; 95% CI, 0.621–1.915), Steinbrocker functional class (1 + 2 versus 3 + 4, full model OR: 0.804; 95% CI, 0.447–1.445), and concomitant use of MTX (yes versus no, full model OR: 1.287; 95% CI, 0.788–2.103) were not associated with a significant difference in the effectiveness rate (all p > .05).

Discussion

Use of biologics alone or in combination with MTX greatly improved health outcomes in patients with RA; however, a substantial proportion of patients do not achieve remission or low disease activity. In addition, these treatments come with notable side effects that challenge their long-term use.

In this PMS, we evaluated the long-term safety and effectiveness of ETN administration in a population of Japanese patients with RA under different dose regimens. ADRs were reported in 37.9% of patients, the majority of them were not serious; the most frequent being injection site reactions (4.4%) and nasopharyngitis (3.3%). Study discontinuation due to ADRs accounted for 12.4% of the study population. Over the whole surveillance period, SADRs occurred in 8.9% of patients and pneumonia was the most common (1.2%), followed by interstitial lung disease (0.9%). In terms of infectious events, use of ETN and other TNF inhibitors has been associated with an increased risk of reactivating latent TB [Citation25,Citation26]. In this study, only two patients with one event each developed TB; thus, incidence of TB in this population of patients was not deemed to be clinically significant. The incidence rate of herpes zoster in this study (IR 1.07 per 100 patient-years) was similar to that reported in a large observational study conducted between 2005 and 2010 in Japan (IR 9.1 per 1000 patient-years), and lower than the incidence rate reported in Japanese patients with RA treated with Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors (IR 4.4 per 100 patient-years) [Citation27,Citation28]. Patients with RA are also at higher risk of developing malignancies than the general population is [Citation29,Citation30]; however, no trend toward increased cancer incidence was noted in this study. Concomitant use of MTX was a factor associated with a decreased risk of developing ADRs and serious infections, which is consistent with previous studies [Citation21,Citation31] whereas concomitant diabetes and advanced age were associated with an increased risk of developing infections and SADRs, respectively. As lurking confounders might affect the results of this analysis, tight monitoring is advisable in the presence of concomitant use of MTX. For instance, concomitant use of MTX in Japanese patients with RA treated with adalimumab was reported to be a risk factor for infections [Citation32]. In conclusion, this PMS did not reveal new safety signals and continuous ETN treatment in Japanese patients with RA remained favorable.

With respect to effectiveness, our data demonstrate that treatment with ETN improved DAS28-4/ESR scores over time in the majority of patients. Reduced disease activity was also demonstrated by increments in the proportion of patients in remission over the 2-year study period. VAS fatigues and mHAQ scores were also significantly improved at every time point compared to baseline. Of note, given that 45.9% of patients were aged ≥60 years, and a combined 61.0% of patients were in either Steinbrocker stage III or IV, this PMS showed good effectiveness of ETN treatment in elderly patients and in patients with advanced RA. Among factors affecting effectiveness, patients with low DAS28-4/ESR scores at baseline showed the least improvements by the end of the observational period compared with patients with a high DAS28-4/ESR score at the beginning of the study. However, this outcome was expected as disease activity is already low in patients with low DAS28-4/ESR scores at baseline. Discontinuation of treatment due to lack of effectiveness was reported in 13.3% of patients. In conclusion, the findings of this study support long-term effectiveness of ETN treatment in Japanese patients with RA.

The limitations of this study include the restriction to a Japanese population with RA and its relatively small size, thus the findings and conclusions may not be generalizable to other patients with RA in Japan and in the rest of the world. Another limitation was the high number of patients who dropped out due to unknown reasons or with missing data. As this was a PMS study, there was no comparator arm; thus it cannot provide insights into the relative safety or effectiveness of ETN versus other bDMARDs.

In conclusion, this long-term study of ETN treatment in Japanese patients with RA showed no evidence of novel safety concerns, and demonstrated that effectiveness was sustained over a 2-year period.

Conflict of interest

H. Yamanaka has received consultant fee, speaker fee, research grant, scholarship donation, or donated research department from MSD, Ayumi, AbbVie, Eisai, Ono, Astellas, Daiichi-Sankyo, Taisho Toyama, Takeda, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Chugai, Teijin Pharma, Torii, Nippon Shinyaku, Pfizer, UCB, Nippon Kayaku, YL Biologics, Bayer, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. T. Koike has received speaker fees from AbbVie, Asuka Pharma, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chugai Pharmaceuticals, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Pfizer Japan, Teijin Pharma, UCB, and consultant fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly Japan, Pfizer Japan, Daiichi Sankyo, and Sanofi. T. Hirose, Y. Endo, N. Sugiyama, Y. Fukuma, N. Sugiyama, N. Yoshii, and Y. Morishima are employees of Pfizer Japan Inc. T. Hirose, N. Sugiyama, E. Yutaka, N. Sugiyama, Y. Morishima, and N. Yoshii are stockholders of Pfizer. N. Miyasaka declared no conflict of interest.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (39.4 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (46.6 KB)Acknowledgements

We wish to thank all patients who participated in this study and medical staff of all participating centers. Medical writing support was provided by Sabrina Giavara, PhD of Engage Scientific Solutions and was funded by Pfizer.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, Funovits J, Felson DT, Bingham CO, 3rd, et al. 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(9):2569–81.

- Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, Carmona L, Wolfe F, Vos T, et al. The global burden of rheumatoid arthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(7):1316–22.

- Yamanaka H, Sugiyama N, Inoue E, Taniguchi A, Momohara S. Estimates of the prevalence of and current treatment practices for rheumatoid arthritis in Japan using reimbursement data from health insurance societies and the IORRA cohort (I). Mod Rheumatol. 2014;24(1):33–40.

- Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL Jr., Akl EA, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(1):1–26.

- Smolen JS, Landewe R, Bijlsma J, Burmester G, Chatzidionysiou K, Dougados M, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(6):960–77.

- Emery P, Breedveld FC, Hall S, Durez P, Chang DJ, Robertson D, et al. Comparison of methotrexate monotherapy with a combination of methotrexate and etanercept in active, early, moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (COMET): a randomised, double-blind, parallel treatment trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9636):375–82.

- Emery P, Kvien TK, Combe B, Freundlich B, Robertson D, Ferdousi T, et al. Combination etanercept and methotrexate provides better disease control in very early (< =4 months) versus early rheumatoid arthritis (>4 months and <2 years): post hoc analyses from the COMET study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(6):989–92.

- Breedveld FC, Weisman MH, Kavanaugh AF, Cohen SB, Pavelka K, van Vollenhoven R, et al. The PREMIER study: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind clinical trial of combination therapy with adalimumab plus methotrexate versus methotrexate alone or adalimumab alone in patients with early, aggressive rheumatoid arthritis who had not had previous methotrexate treatment. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(1):26–37.

- Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Allaart CF, Kerstens PJ, Grillet BA, de Jager MH, et al. Patient preferences for treatment: report from a randomised comparison of treatment strategies in early rheumatoid arthritis (BeSt trial). Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(9):1227–32.

- Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Allaart CF, van Zeben D, Kerstens PJ, Hazes JM, et al. Comparison of treatment strategies in early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(6):406–15.

- Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Allaart CF, van Zeben D, Kerstens PJ, Hazes JM, et al. Clinical and radiographic outcomes of four different treatment strategies in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis (the BeSt study): a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(11):3381–90.

- Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Allaart CF, van Zeben D, Kerstens PJ, Hazes JM, et al. Clinical and radiographic outcomes of four different treatment strategies in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis (the BeSt study): a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(2 Suppl):S126–S35.

- Takeuchi T, Miyasaka N, Kawai S, Sugiyama N, Yuasa H, Yamashita N, et al. Pharmacokinetics, efficacy and safety profiles of etanercept monotherapy in Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis: review of seven clinical trials. Mod Rheumatol. 2015;25(2):173–86.

- Strangfeld A, Richter A. [How do register data support clinical decision-making?]. Z Rheumatol. 2015;74(2):119–24.

- Black N. Why we need observational studies to evaluate the effectiveness of health care. BMJ. 1996;312(7040):1215–8.

- Abe T, Takeuchi T, Miyasaka N, Hashimoto H, Kondo H, Ichikawa Y, Nagaya I. A multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo controlled trial of infliximab combined with low dose methotrexate in Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2006;33:37–44.

- Miyasaka N, CHANGE Study Investigators. Clinical investigation in highly disease-affected rheumatoid arthritis patients in Japan with adalimumab applying standard and general evaluation: the CHANGE study. Mod Rheumatol. 2008;18(3):252–62.

- Kameda H, Ueki Y, Saito K, Nagaoka S, Hidaka T, Atsumi T, et al. Etanercept (ETN) with methotrexate (MTX) is better than ETN monotherapy in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis despite MTX therapy: a randomized trial. Mod Rheumatol. 2010;20(6):531–8.

- Takeuchi T, Kameda H. The Japanese experience with biologic therapies for rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6(11):644–52.

- Miyasaka N, Takeuchi T, Eguchi K. Guidelines for the proper use of etanercept in Japan. Mod Rheumatol. 2006;16(2):63–7.

- Koike T, Harigai M, Inokuma S, Ishiguro N, Ryu J, Takeuchi T, et al. Postmarketing surveillance of safety and effectiveness of etanercept in Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Mod Rheumatol. 2011;21(4):343–51.

- DAS28. Available from: http://www.das-score.nl/das28/en/ [last accessed 21 Jun 2017].

- Pincus T, Summey JA, Soraci SA Jr., Wallston KA, Hummon NP. Assessment of patient satisfaction in activities of daily living using a modified Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire. Arthritis Rheum. 1983;26(11):1346–53.

- Lee KA, Hicks G, Nino-Murcia G. Validity and reliability of a scale to assess fatigue. Psychiatry Res. 1991;36(3):291–8.

- Hamdi H, Mariette X, Godot V, Weldingh K, Hamid AM, Prejean MV, et al. Inhibition of anti-tuberculosis T-lymphocyte function with tumour necrosis factor antagonists. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(4):R114.

- Long R, Gardam M. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors and the reactivation of latent tuberculosis infection. CMAJ. 2003;168:1153–6.

- Winthrop KL, Yamanaka H, Valdez H, Mortensen E, Chew R, Krishnaswami S, et al. Herpes zoster and tofacitinib therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(10):2675–84.

- Nakajima A, Urano W, Inoue E, Taniguchi A, Momohara S, Yamanaka H. Incidence of herpes zoster in Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis from 2005 to 2010. Mod Rheumatol. 2015;25(4):558–61.

- Simon TA, Thompson A, Gandhi KK, Hochberg MC, Suissa S. Incidence of malignancy in adult patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17(1):212.

- Smitten AL, Simon TA, Hochberg MC, Suissa S. A meta-analysis of the incidence of malignancy in adult patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10(2):R45.

- Doran MF, Crowson CS, Pond GR, O’Fallon WM, Gabriel SE. Predictors of infection in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(9):2294–300.

- Koike T, Harigai M, Ishiguro N, Inokuma S, Takei S, Takeuchi T, et al. Safety and effectiveness of adalimumab in Japanese rheumatoid arthritis patients: postmarketing surveillance report of 7740 patients. Mod Rheumatol. 2014;24(3):390–8.