Abstract

Occupational scientists' appreciation of occupational choice has not extended into theorizing the complexities of its situated nature. This paper presents a critical ethnographic study investigating the factors shaping the occupational choices of marginalized young adolescents in a community in South Africa. Drawing on Bourdieu's theories of action, the transactional nature of occupational choice influenced by habitus and doxa and operating through practical consciousness is illustrated. Through network sampling, seven young adolescents, their peer groups and a significant adult in their lives were recruited into the study. Data were generated using photo-voice methods and photo-elicitation interviews, observation and a semi-structured interview with the adult. The analysis yielded the theme, “It's just like that”, illustrating the way in which practical consciousness, habitus and doxa contributed to maintaining patterns of engaging in occupations reflecting the hegemonic discourse of the community of Lavender Hill. The discussion explains the nature of occupational choices, emphasing how the social environment together with collective and contextual histories influences the manner and types of occupational choices made. This shifts the perspective of occupational choice from being an individual construct to understanding how it contributes to occupational injustice.

Occupational choice has been largely overlooked as a topic for analysis and research in occupational science. The focus of this paper is the distinction between established perspectives and an emerging view of occupational choice arising from critical ethnographic research with marginalised youth in a South African context. This evolving view lays a foundation for further theorising of occupational choice as a construct in the occupational science lexicon.

Contextual Framing of Occupational Choice

Occupational choice has been viewed from an individualist perspective, with its functionality framed within social role theory. Early conceptions of occupational choice in the Occupational Behaviour framework (Reilly, Citation1969) and later the Model of Human Occupation (MOHO) (Kielhofner, Citation2008) drew on social role theory, individual development across the lifespan and volition to show how occupational choices were shaped by personal and environmental factors. Both MOHO and the Occupational Behaviour framework defined the essential features of occupational choice as a long-term process through which individuals developed their skills and abilities, self-interests and self-evaluation across their life span (Poulsen, Citation1980; Webster, Citation1980). These features emphasise the person's contribution to shaping occupational choices with scant consideration of the influence of historical, economic, cultural and political dimensions of the environment.

Accentuating the deliberate and rational nature of occupational choice, a position promoted by the MOHO (Kielhofner, Citation2008), the definition excluded the spontaneous and contextually embedded nature of occupational choice operating beyond personal volition. The locus of choice was placed primarily within the person, focusing on how he or she pursued roles within existing and accessible social structures (Kielhofner, Citation2008; Poulsen, Citation1980; Webster, Citation1980). Exposure to opportunities within the environment only mattered in so far as they influenced a person's selection, maintenance and development of occupational roles (Kielhofner, Citation2008). Occupational choices occurred as a function of a person's motivation and sense of control in selecting occupations in which to participate (Kielhofner, Citation2008). This viewpoint did not lend itself to questioning individuals' (acquired) socio-historical circumstances, the influence of their intersectional identities and positionality within contexts (that is, the way that relational qualities of identity affect the power to act) and the way that those factors affected occupational choices. Instead it enhanced and endorsed the maintenance or adaptation of existing occupational roles by not calling into question the social positions associated with such roles, or the discourses and power structures that governed how these roles evolved and were maintained. It was assumed that occupational choice was equally available to all people. Professional attention was directed to the outcome of occupational choices, especially the health giving benefits of participating in occupations.

The value of occupational choice was asserted to positively contribute to the way individuals experienced their community membership and health (Minato & Zemke, Citation2004) by creating a patterned structure to their time-use. While the value of the sociocultural dimension of the context and an etic perspective of occupational choice (Pierce, Citation2003) was deemed important in selecting relevant occupations, critique of the restricted opportunities prevailing in many contexts and shaping occupational choice was neglected. The status quo of occupational choices for groups was accepted and promoted, in that it was recognised that if individuals rarely saw members of their social group participating in particular occupations, those occupations would, over time, take on meanings of exclusively belonging to ‘others’ (Pierce, Citation2003). The ways in which established patterns of occupational choice might contribute to social inequalities or occupational injustices was not considered. It was, however, recognized that choosing to participate in different occupations produces an individual's social identity just as social identity influences a person's participation in occupations (Polatajko, Molke, Baptiste, Doble, Santha, & Kirsh, Citation2007). The recognition that the social context promotes some choices and hinders others warrants further investigation, as efforts to promote social inclusion and community development come into prominence.

Occupational Choice as Shaped by Practical Sense

Action theories have recently been promoted to make sense of occupation in ways that overcome the duality between person and environment. That shift in thinking gives due recognition to occupational engagement as a form of social action that occurs in multiple contexts (Dickie, Cutchin, & Humphry, Citation2006). From that perspective, occupational choice serves as a mediating factor, contributing to the way in which people, as agents of their own actions, navigate their occupations within social structures. Bourdieu (Citation1977) used human action to refer to agency and the way in which people act upon their social worlds. The dialectical interconnection between agents and their social structures recognizes that agents, rather than structures, act, but that structures sway the agent's actions (Layder, Citation1994).

Bourdieu's (Citation1977) concepts of habitus, capital and social field have utility for understanding how occupational choices mediate occupational engagement within contexts. Habitus refers to an agent's set of dispositions, which are formulated and recreated through objective social structures, individual and collective history (Mahar, Harker, & Wilkes, Citation1990). It exists as an embodied history (Bourdieu, Citation1994b) that shapes occupational choice by guiding what should reasonably be done in a given situation arising in a particular context. Over time, sets of dispositions develop and, expressed through habitus, enable distinct occupational choices to be made. Given that habitus is a facilitating construct (Mahar et al., Citation1990), its influential rather than deterministic effect on occupational choice should be noted. The emerging dispositions of habitus are grounded in experiences and exist as pre-conditions to an agent's reflections and actions. These pre-conditions frame the occupational choices that an agent makes, so that their actual experiences substantially influence the occupational choices that are made. The proposition that occupational choice occurs through the unconscious mechanism of habitus does not stand against a person's capacity for reflexive, intentional and conscious actions. Instead, it highlights habitus and the pre-conditions that prevail within particular fields, where different forms of capital operate.

Capital refers to objectively valued resources within a particular social field (Bourdieu, Citation1994b). Various forms of capital, such as symbolic and economic, are known to contribute to the social positions that a person holds within and across social fields (Bourdieu, Citation1994b). Agents use their occupational choices to leverage their social position while engaging in occupations. In making occupational choices, their social positions are contrasted with the positions held by others within particular and diverse social fields. The prevailing forms of capital influence how different social positions are valued and which occupational choices are made (Galvaan, Citation2010, Citation2012). Working synchronously, the constraints of habitus, together with the conditions existing within various social fields of action, facilitate or constrain the choices that are made.

The dialectic between habitus, capital and social field is reflected in the unspoken and unexamined assumptions that individuals and groups hold. Referring to these tacit presuppositions as doxa, Bourdieu (Citation1994b) identified that doxa sets the parameters of a person's power to act in the field and, in so doing, contributes to social reproduction. An individual or group's doxa would influence their presuppositions about their power to make different occupational choices. For a community sharing a common doxa, particular patterns of occupational choice would be evident. However, an agent always has the prerogative to deploy various strategies that regulate the positions that they take up in each field. Hence, when making occupational choices, agents may deploy several strategies that reflect the common or a different doxa. Reproduction or reconversion strategies emerge as intuitive products of knowing the rules of the field (Bourdieu, Citation1994b). These strategies either reproduce existing social positions or, through conversion, establish new social positions through the occupational choices made. Exploring how doxa and its associated strategies operate, when occupational choices are made in fields characterized by adverse socio economic constraints, allows for a more nuanced understanding of occupational engagement in such contexts to emerge. Informed by an understanding that occupational choices are co-constructed and embedded within contexts, this paper describes a study that set out to understand how young adolescents experiencing social inequalities in a historically marginalised community in South Africa made occupational choices.

Exploring Occupational Choice through Critical Ethnography

The research was conducted with young adolescents living within the community of Lavender Hill, a context characterized by social inequality, structural under development and occupational risk. Exploring occupational choice within this socio-historical and political context allowed for an in-depth investigation of how young adolescents' occupational profiles reflect occupational injustices and how this manifests in the factors shaping and the nature of their occupational choices.

Lavender Hill is a community situated in the southern part of Cape Town in South Africa. The Lavender Hill residential area was originally established under an Apartheid policy, namely the Group Areas Act (Citation1950) which enforced racially segregated residential areas. Lavender Hill was declared a coloured preferential residential area, where the coloured identity category referred to people who descended from “Cape slaves, the indigenous Khoisan population and other people of African and Asian descent who had been assimilated into Cape colonial society by the late nineteenth century” (Adhikari, Citation2006, p. 468). Contrary to the way that the term ‘coloured’ was used internationally, ‘coloured people’ in South Africa were seen as being of mixed race and positioned in an intermediate status on the racial hierarchy, being neither part of the numerically black majority or white minority (Adhikari, Citation2006). Denying the richness of their creole identities, the coloured category was taken legislatively and ideologically to include sub-groups such as the Malays, the Griquas, Basters and Namas (Adhikari, Citation2006). The Group Areas Act operated in unison with the Reservation of Separate Amenities Act (Citation1953), which segregated public premises, vehicles and services on the basis of race. These laws not only made the unequal allocation of facilities for different races possible, but also legalized the complete exclusion of coloured people from development opportunities allocated to white people. Segregated residential, educational and employment areas surrounding Lavender Hill burgeoned, reflecting the characteristic inequality of contexts originating from the apartheid ideology. These socioeconomic origins remain visible in the poverty, gang violence and poor infrastructure in Lavender Hill and surroundings areas. The social inequality between Lavender Hill and previously designated white areas in close geographic proximity is distinct.

The current education profile of adults over the age of 20 in Lavender Hill shows that 4% have no schooling while 35% only have primary school education (StatsSA, Citation2001). A quarter of a percent of adults have tertiary education. Despite school-going children in such areas having more opportunities in the new South Africa, they remain restricted by the apartheid legacy of a low, working socio-economic class (Abrahams, Citation2007-2008). Raised by parents or caregivers who were disadvantaged by the formal education system and have little hope of prosperity, these children face numerous challenges in realising their potential and achieving their constitutional rights. Adverse social circumstances include an overcrowded and poorly resourced schooling system that renders young adolescents vulnerable to under development. Nationally, the most frequently reported non-natural causes of death amongst youth aged between 15-29 years are firearms and sharp objects that have found their way into social environments, including schools (Donson, Citation2008). The vulnerability of youth between the ages of 10-14 that leads them to such fatal behaviour is a concern for educators, the police, parents and the South African society.

The socio historic background of and social injustices prevalent in Lavender Hill provided the context within which the following research question arose: what occupations are engaged in and how are occupational choices made by youth aged between 11-14 years living in a marginalised community? Recognising the social inequality and injustice prevalent in Lavender Hill, the use of critical ethnography allowed for an investigation of practices, such as occupational choice, in relation to the influence of the wider context. Critical ethnography is known for situating phenomena within the wider context and appreciating how power and other influencing factors come to bear on what exists. This methodology involves seeking not only to uncover sociocultural knowledge about a group, but also patterns suggesting social injustice (Sayer, Citation2000). Occupational injustice is a form of social injustice (Townsend & Wilcock, Citation2004); it thus follows that critical ethnography could reveal patterns of occupational engagement or occupational choice leading to the occupational injustice experienced by young adolescents in Lavender Hill. Through its critical stance, critical ethnography has the potential to raise consciousness about the injustice, inequalities and hegemonies of social life (Korth, Citation2002).

Raising consciousness about the nature of occupational choice for young adolescents in Lavender Hill would assist in exploring ways to confront the inequalities they experience. Understanding how occupational choices operate in the context of social inequity allows for political expression of the disadvantage experienced, resonating with the value orientation shared by critical researchers in their concern with social inequalities (Carspecken, Citation1996). This is made possible through the exploration of the culture, community and everyday circumstances of groups, with the goal of seeing what is and what could be possible (Thomas, Citation1993) with regards to occupational choice.

Criterion-based selection (LeCompte & Preissle, Citation1993) was used to identify the sample, with the criteria becoming clearer as the study unfolded and as aspects of occupational choice that required further exploration were identified. Drawing on knowledge of the community of Lavender Hill, developed over 5 years whilst developing a practice-learning site in primary schools there, the focus of the research, and the common characteristics of young adolescents who lived in Lavender Hill, the following criteria were applied. Participants had to be aged 11 to 13 years, as this is a key stage of identity formation that impacts on young adolescents' occupational choices, that will shape their futures. Also, young people are known to engage in behaviours leading to fatalities in beginning to enter gang related activity soon after this age. Understanding their occupational choices might generate insights that could be applied to interventions to change their community's prospective story.

Seven young adolescents were included in the study. The number of participants was determined by theoretical and practical factors. The theoretical endeavour to generate understanding of the nature of occupational choice required in-depth information from each of the participants. My prior practice and research experience alerted me to the need to patiently nurture relationships with participants who would require a solid basis of trust from which to share the dynamics of their life world. This meant that I needed to be generous with the time I expected to spend with each participant. The anticipated time-intensive data generation strategies also bore financial costs, limiting the amount of data that could be generated. I conceded that while the study objectives would explore the nature of and the factors that influenced young adolescents' occupational choices, the full diversity prevalent in a community such as Lavender Hill could not be captured. I assumed that significant adults may be instrumental in their occupational choices and therefore asked the selected young adolescents to identify a significant adult who they agreed could to be interviewed in order to for me to gain another perspective.

Sequential and progressive application of network sampling was applied whereby a preceding participant identifies successive participants (LeCompte & Preissle, Citation1993). I initiated participant selection by being present in the play spaces provided by occupational therapy students at two primary schools in Lavender Hill. These were essentially indoor play areas at each of the schools. I was able to find an initial participant through explaining my study to children who enquired. Once I recruited a participant and progressed substantially with data generation with that person, he or she introduced me to another possible participant. In this way the seven participants were selected over the course of the study. The process of participant selection occurred over a 4-year period.

Selecting the sample based on participant referrals allowed individuals to be accessed based on the knowledge of the groups that they belonged to (LeCompte & Preissle, Citation1993). During network sampling, the variation of the criteria was based on comparisons across dimensions of the sample (LeCompte & Preissle, Citation1993). The progressive sample selection meant that recruitment of successive participants was informed by insights gained and questions raised during data generation. Seven participants, four boys and three girls, their peer groups and an identified adult associated with each, participated in the interviews. Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Cape Town's Health Sciences Ethics Committee, and through the Western Cape Education Department's Ethics approval process. Consent and assent was obtained from all participants and their parents or guardians.

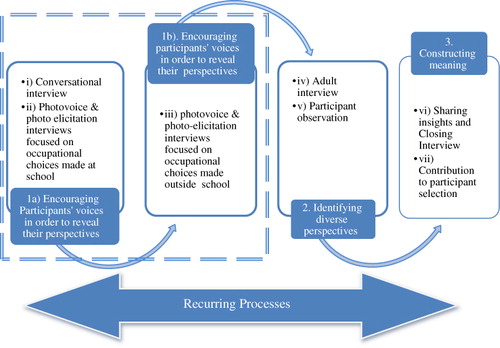

My emphasis centred on establishing and continuing an interpersonal contract with young adolescents in a way that respected their personal boundaries. Consistent with Melton's (Citation1992) recommendations, I was able to clearly convey to and discuss with the participants the potential risks and exposure through their ongoing involvement in the study. Through discussing the risks with them throughout the research process, I was able to manage the research process to ensure that ethical principles were upheld. This was achieved by gathering data over a prolonged period while consistently explaining the expected exposure to the participants and gauging their responses. Furthermore, adopting a stepwise, process-oriented approach to data gathering allowed for repeated opportunities to firstly, check that the participant was comfortable with the research demands and secondly, eager to continue. The deliberate and considerate way that I engaged with and viewed participants ensured that ethical principles were fundamentally integrated into all the research processes and procedures. The data gathering methods used and the processes of critical ethnography followed over a 2-year period of engagement with each participant, reflected in .

While the processes are represented separately in the figure, in reality they recurred and continued to shape the way forward in generating data. Participants generated photographs using photo-voice methods and photo-elicitation interviews were conducted (Mitchell, Citation2008). These data gathering methods engaged the interest of the youth, and allowed for fuller explanations and flow between interviews in a way that solely verbal interviews could not achieve (Mitchell, Citation2008). A conversational approach was particularly important for marginalised young adolescents in Lavender Hill who, for a variety of reasons, may have been reticent to express themselves. The two parts of the first process were iterative and incrementally encouraged the participants to identify their occupational choices through the repetition of the data gathering methods. These included semi-structured interviews based on the participants' narratives of the occupational choices made at school and then at home as captured in photographs that they produced.

The interview process based on the photographs occurred over an 8 month period. Each participant participated in multiple interviews; these were only concluded once they had fully discussed all the photos that they had taken. The lengths of the interviews were determined by the time that it took to discuss all the photos that participants had taken, with each participant taking two sets with at least 20 photos per set. This allowed opportunities for continuous engagement with each participant during the first part of data generation.

The second process involved conversations with significant adults to gain diverse perspectives on the participants' accounts, providing critical insights on the disjunctions and confluences between the youth and adult ethnographies emanating from the research question. Through interviewing the participants' parents, I was able to hear their views and contrast this with the perspectives that I obtained from the participants. I then had the opportunity to discuss this perspective with the youth participants before initiating the participant observation sessions at the local games shops, the beach, or the streets where they played and in their homes. The rest of the participant observations occurred during or before the interviews with each participant. This provided me with insight into how their diverse perspectives coexisted. The last process of constructing meaning involved integrative reflections by participants in making sense of their occupational choices in their stories during the research period.

QSR Nvivo (QSR International Pty Ltd, Citation1996-2003) computer software package was utilized to manage the data. Data analysis occurred incrementally using the pragmatic horizon approach, which recognises that ideas couldn't be understood without simultaneously understanding the “horizon” from which they emerge (Carspecken, Citation1996). People, such as young adolescents, hold particular ideas about and make claims related to the horizon that they are situated within. Comprising elements of life-world and systems, a horizon constitutes the pragmatic background within which young adolescents would make their claims or statements about occupational choices, either as communicative action or through another type of action. Carspecken (Citation1996) noted, “meanings are always experienced as possibilities within a field of other possibilities” (p. 96). Pragmatic horizon analysis identifies five main categories of validity claims within the horizon of meaningful acts (Carspecken, Citation1996). These categories direct the analysis towards more precise identification of meaning. Contrasting the meaning derived from the various participants and data sources allowed for iterative verification of the meanings that emerged in the findings.

Member checking, prolonged engagement, triangulation and peer debriefing were used as strategies to enhance the rigor of the study (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985). Prolonged engagement (LeCompte & Preissle, Citation1993) involved spending adequate time observing various aspects of the setting, speaking with a range of people, and developing relationships and rapport with young adolescents in Lavender Hill. Methods triangulation (Patton, Citation2001) meant contrasting the data generated through photovoice and photo-elicitation interviews vis-a-vis the observation sessions, interviews with significant adults and field notes to evaluate the consistency of the findings generated through various methods of data collection. Reflexivity (Thomas, Citation1993) during the research process entailed a conscious examination of how I, as an active creator of knowledge, affected the data gathering, analysis and representation of the findings.

The data analysis for the entire data set and each of its components allowed for questioning of what claims are implied in action. With regards to the photographs, the whole and components of photographs were examined for the evidence that they present (Ewald & Lightfoot, Citation2001) with reference to occupational choice. This was followed for the entire collection and each photograph within it. Most data were collected in Afrikaans and data analysis was completed prior to translation of selected quotes for presentation here.

Findings

The findings consist of a single theme and two categories as presented in . In this paper I explain the nature of occupational choice as I came to understand it through the relationship between the categories, “My friends and I” and “Being sussed” and the theme; “It's just like that”. Elements of the two categories are introduced in this section to provide understanding of how they shape the theme. The relationship between the theme and categories are explained using data derived from the photo elicitation interviews and participant observation sessions. Pseudonyms are used throughout.

Table 1: Theme, Categories and Sub-categories

The category “My friends and I” speaks to the socially, historically and economically situated nature of the occupational choices made by young adolescents in Lavender Hill. The nascent culture in their peer groups affected their occupational choices, which reflected what they commonly saw others, especially adults, in their community as doing. Their locus of control over the occupational choices was not just individually controlled but was shared with the subgroups that they were a part of. Social processes at group and societal levels were inseparable from individual participants' occupational choices, which reflected the embedded collective identity of the community of Lavender Hill.

The category “Being sussed” described the self-perpetuating and predictable nature of the participants' occupational choices. Following expected and predictable occupational choices led young adolescents to develop ‘know-how’ of what they had to do to live and achieve in Lavender Hill. Making occupational choices in ways that followed how to ‘be’ in Lavender Hill ensured that they fitted in with the prevalent social and occupational patterns in the community. This “fitting in” was significant as it gave participants a source of power and access to material, symbolic and relational capitals within their everyday lives. It reflected the dominant doxa in the community of Lavender Hill.

It's just like that: Occupational choice shaped by practical consciousness

The kinds of occupations chosen and the way that these choices were made gave rise to the paradoxical and circular nature of the participants' occupational choices, captured in a single theme “It's just like that”. Echoing a colloquial Cape Flats phrase, the theme is patterned on taken-for-granted ways of living and doing. It is usually invoked to testify that someone unequivocally affirms and agrees with the view being put forward, despite knowing that conflicting views and ways of doing may hold true. Taking for granted of what is, shaped the young adolescents' occupational choices. Through following patterns of occupations similar to those of people living in Lavender Hill, as reflected in the category “My friends and I”, the young adolescents reproduced intergenerational patterns of occupational choices and occupational engagement reflective of colonial and apartheid influences on that community.

The reproduction of patterns of occupational choice contributed to the congruent and continuous patterns of occupations between individuals, sub-groups and the community, and the community's position in society. Although they were aware that different ways of doing existed, the participants did not conceive that these may have been possible for them in Lavender Hill. Instead, they accepted and perpetuated the rules on how to act and be in that place. While they made many decisions about their occupations, these operated within a limited range of occupational choices. The congruence between personal and collective action was made visible through the kinds of opportunities that each young adolescent sought to pursue. This was evident in the sub-category describing the interface between individual participation and the peer group as a collective. Their pragmatic horizons created fields of action, which encouraged their pursuit of social prestige in ways that held value within their immediate contexts. Their choices did not develop their capabilities to generate diverse forms of occupational patterns that would allow them to navigate diverse contexts beyond the world of Lavender Hill. The constraints of the structure of the community of Lavender Hill and their contribution to the production and reproduction of the structure was evident in their acceptance of the available, limited occupational choices.

The theme ‘it's just like that’ speaks to the particular habitus and reproductive strategies of doxa, which repeated prevailing social positions and in so doing, informed how choices were made. Referred to as ‘practical consciousness’, the young adolescents were aware of which occupational choices could be made within the constraints of that community. The following story illustrates how practical consciousness operated amongst Marco (a key participant) and a group of friends who found a large, inflatable boat at a nearby rubbish dump. They planned to use the boat to play at a nearby ‘vlei’ (small lake) and decided to walk along the highway to a petrol station where they would pump up the boat. After the labour-intensive 30 minute walk, carrying the boat as a team, they finally arrived at the petrol station where a woman offered them 50 rand to buy the boat. The group of friends decided to sell it to her as they were attracted to the money. When walking back to Lavender Hill they spoke about the missed opportunity for a novel occupation that they gave up in exchange for the R50. They immediately returned to the petrol station, paid the R50 back and retrieved the boat, after which they went to the vlei and had fun sailing and hiding between the reeds. They enjoyed the afternoon, deflated the boat and carried it back to Lavender Hill.

The emergent way that this occupational choice came about while they were scouting around at the rubbish dump highlighted that they were alert to opportunities to choose to engage in occupations and knew where to find such opportunities in context. Although the local rubbish dump is conceived as a dangerous place where one may pick up an infection or risk being injured, this was not a deterrent for them. Being alert to opportunities to make occupational choices resulted in Marco and his peers discussing the lost opportunity and deciding to make a different occupational choice. The peer group's resourcefulness in seizing opportunities when they noticed that these were accessible illustrates how their shared understanding of habitus operated. Seizing opportunities occurred against a background of tight-knit relationships between peers, but also within the limitations of available opportunities.

This story also captures the acceptance associated with the nature of occupational choices. The participants' occupational choices were expected to be as they were and this was accepted by most people in their context without contestation. The occupational choices demonstrated here shows some rational consideration about choice. However, even underlying this rationality was their practical consciousness, informed by a particular habitus developed in the field of action in Lavender Hill. Practical consciousness ultimately shaped their occupational choices, which unfolded in a progressive manner. Occupational choice occurred as a component of occupational engagement and not just as an outcome of a once off or single decision to engage in an occupation.

The intergenerationally patterned and socio-historically structured sense of ‘what is done in Lavender Hill’ that the young adolescents developed over time became their automatic, default guide for making and driving their everyday occupational choices. The constraint on everyday occupational choices remained uncontested since most others in the Lavender Hill community expected that they would make choices to participate in the regularly seen occupations.

The category “Being sussed” showed that participants made occupational choices by drawing on their positional power in relation to their social situation. Participants thus drew on parts of their identities that would give them most power in a situation while making occupational choices. For example, a 13 year old male participant, Clino, used the power associated with his age and gender identity to force a younger girl to participate in an occupation with him. In one instance, while taking photos of break time games, he pulled her into a photo despite her protests. Participants sought opportunities where they were familiar with using their positional power to achieve success.

Achieving success in their occupational performance allowed them to maintain or even increase their social status within their peer group, or with the community, in that they were able to manipulate the forms of capital, especially symbolic capital that they had access to. It was apparent that they used different aspects of their intersectional identities to assert their positional power. This strategy held inevitable short-term benefits for them, but did not give them access to further opportunities, especially not opportunities that would expand their repertoires into other fields of action. Instead, it contributed to maintaining their current social and class position and reproduced the culture associated with performing occupations in Lavender Hill.

The inevitability of occupational choices was evident, for example when speaking about smoking tobacco. Participants recognised that smoking tobacco was bad for their physical health, but smoked anyway. Smoking was an expected occupational choice for all in Lavender Hill, usually occurring as a shared activity while ‘hanging out’, which refers to informal socialisation in public spaces, such as street corners. Richard matter-of-factly explained why he would not smoke continuously: “because you can get chest cancer and all that”. Notwithstanding its health risks, he had experimented with smoking tobacco and only stopped because his mother had caught and scolded him. Ironically, when asked about his mother's use of substances, he proudly indicated that: “No, only smokes cigarettes, Stuyvesant”. Familiar with the brand that she smoked, he approved that she only smoked tobacco cigarettes and not other substances. The view of minimising the risks associated with tobacco prevailed over the view of possible risks to his mother's health, despite the extensive public health education regarding tobacco use. This was confirmed when I accompanied Richard to the shop on an errand for his brother. He revealed that he occasionally took a puff on his mother's cigarette and that he saw this as insignificant.

Similarly, Kimmy spoke about spending time with her friends, referring to smoking tobacco as “we just smoking here, we doing nothing”. Smoking tobacco was viewed as normative and invisible. It was supported in the community, where it was common for adolescents and adults to smoke tobacco in public. Cigarettes were made freely and easily accessible and sold singly to children at the local shops, home shops or street vendors, despite this being unlawful. It was known by all that children had opportunities to experiment with smoking tobacco from as young as age 10, and that by the time that they were 13 they could be smokers. It was then regarded as a blessing that they were ‘just’ smoking tobacco and not substances such as dagga (marijuana), sniffing glue and tik (methamphetamine). When asked who could buy these substances from the drug merchants, Monash explained:

Is not normal, you can't sell it to any person, you have to be like 20 or 18 there, but not here, like 15, 13, 16 there.

Discussion

This study showed that the constraints of the context affected the occupational choices that young adolescents thought were possible. Their inculcated practical consciousness reproduced constrained patterns of occupational choices. This reproduction contributed to re-creating social inequalities, perpetuating occupational injustices.

The situated nature of occupational choice

Contextual constraints occurred not only as an external influence, but also presented as internalised by young adolescents. Occupational choices were made during rather than only prior to engaging in occupations, as assumed in extant literature (Kielhofner, Citation2008; Pierce, Citation2003). Consistent with the way in which Dewey's ends-in-view is proposed to influence the experience of participating in an occupation (Kuo, Citation2011), the meaning attributed to and the purpose derived from an occupation evolved during occupational engagement, influencing the emergent occupational choices that the adolescents could make. The meaning and purpose co-constructed in the context shaped what occupational choices prevailed. Attributions of meaning and purpose were guided by practical consciousness arising from exposure to particular and patterned ways of acting.

Grounded in practical consciousness, occupational choices emerged as both deliberate and conscious, and also spontaneous and unconscious. Bourdieu (Citation1977) explained that individuals' practical consciousness is informed by habitus and dispositions that are developed over time and that are often consistent with the doxa of communities where they live. Young adolescents in Lavender Hill were very well aware that they could make occupational choices to engage in certain occupations, such as those associated with risk behaviours and violence, since many people in their community commonly engaged in these. By operating through practical consciousness, occupational choice served the particular field in which it was situated. The findings of this study showed that economic and symbolic forms of capital were particularly dominant in shaping not only what, but also how, choices were made.

Occupational choice, power and opportunity

When, as in South Africa, collective histories and experiences entail colonialism and continued racial and socio-economic class inequalities, occupational choices commonly made by marginalized groups sustain situations of occupational injustice (Galvaan, Citation2010). Young adolescents learnt how to live, be and do in Lavender Hill, based on their experiences of living under the prevalent conditions in their community and knowing what was reasonable there. Their contextually developed practical sense led them to make occupational choices that represented their positionality and that of their community within the social hierarchy. Their occupational choices also reflected their internalisation of positions of power that could be occupied in Lavender Hill. This positionality limited the occupational choices they felt entitled to. Internalisation of limitations as a consequence of class and positional power occurred since limits on thoughts, perceptions, expressions and actions are usually established by historically and socially situated conditions (Bourdieu, Citation1994a).

The products of these conditions, such as constrained intergenerational patterns of occupations, are internalised by agents, placing limits on their thinking and actions and deterring them from responding in innovative ways (Bourdieu, Citation1994a). The young adolescents tended not to question how their thoughts and decisions may have been limited by their historic, cultural, social and economic conditions. Instead, the match between the young adolescents' internalisation of the conditions led them to making occupational choices that showed cohesion between their habitus and doxa.

Perpetuation of the operant doxa in Lavender Hill contributed to a restricted range in their patterns of occupations, thereby limiting their chances of developing occupational repertoires required by or applicable in another doxa outside Lavender Hill. Compromised occupational choice prevented the development of dispositions that are flexible and durable in different fields, especially ones that might give them access to economic capital. Those limitations of choice challenge the assumption that promoting power in a field is sufficient for promoting occupational justice across fields. Rather, the way in which power affects occupational choices in particular and diverse fields has to be investigated, as that would allow fuller appreciation of those situations and contexts in which agents are able to assert their power.

In addition to constraints being externally imposed, as in occupational deprivation, occupational marginalisation and occupational apartheid, the reproduction of occupational choices as embodied by habitus and practical consciousness means that the agents themselves may contribute to sustaining situations of occupational injustice. Inculcated practical consciousness contributed to their domination, rendering the inequality and injustice invisible. The idea that people contribute to occupational injustice is not to attribute blame or causality, but provides another lens with which to analyse the factors that contribute to perpetuating occupational injustice.

Furthermore, since the restricted patterns of occupations were in keeping with what was expected of members of low socio-economic status, it contributed to maintaining social inequalities. Wilcock (Citation1998) identified that occupational determinants create conditions for particular occupations to emerge and that this understanding aids insights into occupational risks. Analysis of the occupational determinants from the perspective of the inequalities that they sustain between groups provides further understandings of the complexities of occupational injustice. The occupations that would normally be performed by adolescents, for example, were restrictive. The suggestion that occupational enrichment, in response to occupational deprivation, should create opportunities for occupations that coalesce with those that an individual might usually perform (Molineux & Whiteford, Citation1999) therefore would not stand. In this case the occupations that were part of the norm was part of the problem that had to be addressed. Promoting change would have to be levelled at raising consciousness about the oppressive, hegemonic reproduction through internalisation associated with the norm, together with challenging contextual conditions.

Given that the way in which occupational choice contributes to social reproduction is influenced by structural, contextual and personal factors, it is proposed that creating opportunities through introducing a wider range of opportunities for participation in occupations is insufficient for promoting occupational justice and social inclusion. While the presence of many opportunities holds potential, the extent to which these are accessed and engaged with is limited when social inequality prevails. This is so because although options may be available, the power and the right to choose may be curtailed by internalised oppression. Consequently, the existence of opportunities to participate in occupations may not translate into changes in actual occupational performance. The young adolescents' understanding of what occupations they could imagine themselves participating in restricted their occupational choices.

Conclusion

In describing the contextually situated nature of young adolescents' occupational choices, this paper has expanded the occupational science discourse by identifying and explaining the phenomenon of occupational choice as it occurs in a marginalised community. While a limitation of this study is that the occupational choices of only one group was investigated, the findings provide useful insights into the construct of occupational choice. The study highlighted the value of attending to the process and outcomes of occupational choices. The findings illustrated that patterns of occupational choices were reflective of hegemonic and historical discourses associated with colonialism and apartheid. These choices operated through practical consciousness and doxa. The findings reveal that perpetuating constrained patterns of occupational choices contributes to occupational injustices and social inequalities. Recognising the relationship between promoting occupational choice and social inequality is fundamental to the occupational justice goal of facilitating social inclusion. Through appreciating the personal, relational, socio-historical, socio-economic and cultural contexts of occupational choice, the factors that guide occupational choices and perpetuate occupational injustices may be more effectively considered. This may provide a way of re-conceptualising interventions aimed at promoting occupational choice and eradicating occupational injustices. In particular it reveals the need to adopt a perspective of occupational choice where occupations are seen as transactional and where occupational choice is seen as a collective, historically situated construct.

Acknowledgements

This study was completed as part of the requirements of the PhD program in Occupational Therapy, Department of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa. Appreciation is extended to the dissertation supervisors, Professor Seyi Ladele Amosun and Associate Professor Lana van Niekerk, both from the Department of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Cape Town at the time of the study. Funding support was received from the Thuthuka Program of the South African National Research Foundation.

REFERENCES

- Abrahams, R. (2007–2008). General Managers Report: CAFDA Annual Report. Cape Town: Cape Flats Development Association.

- Adhikari, M. (2006). Hope, fear, shame, frustration: Continuity and change in the expression of coloured identity in white supremacist South Africa, 1910-1994. Journal of Southern African Studies, 32(3), 467–487. doi:10.1080/03057070600829542

- Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of theory of practice. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1994a). Structures, habitus, power: Basis for a theory of symbolic power. In N. B. Dirks, G. Eley & S. B. Orthrer (Eds.), Culture, power, history: A reader in contemporary social theory (pp. 155–199). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1994b). The logic of practice (R. Nice, Trans.). Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Carspecken, P. (1996). Critical ethnography in educational research: A theoretical and practical guide. New York: Routledge.

- Dickie, V., Cutchin, M. P., & Humphry, R. (2006). Occupation as transactional experience: A critique of individualism in occupational science. Journal of Occupational Science, 13(1), 83–93. doi:10.1080/14427591.2006.9686573

- Donson, H. (2008). A profile of fatal injuries in South Africa: Annual report for South Africa based on the National Injury Mortality Surveillance System: MRC-UNISA Crime, Violence and Injury Lead Programme. Tshwane: Medical Research Council.

- Ewald, W., & Lightfoot, A. (2001). I wanna take me a picture: Teaching photography and writing to children. Boston: Centre for Documentary studies in association with Beacon Press.

- Galvaan, R. (2010). A critical ethnography of young adolescents' occupational choices in a community in post-apartheid South Africa. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa.

- Galvaan, R. (2012). Occupational choice: The significance of socio-economic and political factors. In G. E. Whiteford & C. Hocking (Eds.), Occupational science: Society, inclusion, participation (pp. 152–161). Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. doi:10.1002/9781118281581.ch11

- Group Areas Act (1950). Retrieved from http://www.disa.ukzn.ac.za/index.php?option=com_displaydc&recordID=leg19500707.028.020.041

- Kielhofner, G. (2008). Model of human occupation: Theory and application. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams and Wilkinson.

- Korth, B. (2002). Critical qualitative research as consciousness raising: The dialogic texts of researcher/researchee interactions. Qualitative Inquiry, 8(3), 381–403. doi:10.1177/10778004008003011

- Kuo, A. (2011). A transactional view: Occupation as a means to create experiences that matter. Journal of Occupational Science, 18(2), 131–138. doi:10.1080/14427591.2011.575759

- Layder, D. (1994). Understanding social theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- LeCompte, M., & Preissle, J. (1993). Ethnography and qualitative design in educational research (2nd ed.). London: Academic Press.

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Mahar, C., Harker, R., & Wilkes, C. (1990). The basic theoretical position. In R. Harker, C. Mahar & C. Wilkes (Eds.), An introduction to the work of Pierre Bourdieu (pp. 1–25). London: MacMillan.

- Melton, G. B. (1992). Respecting boundaries: Minors, privacy and behavioural research. In B. Stanley & J. E. Sieber (Eds.), Social research on children and adolescents: Ethical issues (pp. 65–87). Newbury Park: Sage.

- Minato, M., & Zemke, R. (2004). Occupational choices of persons with schizophrenia living in the community. Journal of Occupational Science, 11(1), 31–39. doi:10.1080/14427591.2004.9686529

- Mitchell, C. (2008). Getting the picture and changing the picture: Visual methodologies and educational research in South Africa. South African Journal of Education, 28, 365–383.

- Molineux, M., & Whiteford, G. (1999). Prisons: From occupational deprivation to occupational enrichment. Journal of Occupational Science, 6(3), 124–130. doi:10.1080/14427591.1999.9686457

- Patton, M. (2001). Qualitative evaluation and research methods (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Pierce, D. (2003). Occupation by design: Building therapeutic power. Philadelphia, PA: F. A. Davis.

- Polatajko, H., Molke, D., Baptiste, S., Doble, S., Santha, J., & Kirsh, B. (2007). Occupational science: Imperatives for occupational therapy: Occupational choice and control from the perspectives of Bonnie Kirsh. In E. Townsend & H. Polatajko (Eds.), Enabling occupation II: Advancing an occupational therapy vision for health, well-being and justice through occupation (pp. 63–80). Ottawa: Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists, ACE.

- Poulsen, C. (1980). Juvenile delinquency and occupational choice. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 34(9), 565–571. doi:10.5014/ajot.34.9.565

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (1996-2003). NVivo. Retrieved from http://www.qsr.com.au/

- Reilly, M. (1969). The educational process. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 23, 299–307. doi:10.5014/ajot.23.3.299

- Reservation of Separate Amenities Act (1953). Retrieved from http://www.disa.ukzn.ac.za/index.php?option=com_displaydc&recordID=leg19531009.028.020.049

- Sayer, R. A. (2000). Realism and social science. London: Sage.

- Statistics South Africa. (2001). Census 2001. Pretoria: Stats SA.

- Thomas, J. (1993). Doing critical ethnography. London: Sage.

- Townsend, E., & Wilcock, A. (2004). Occupational justice and client centred practice: A dialogue in progress. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71(2), 75–87. doi:10.1177/000841740407100203

- Webster, P. (1980). Occupational role development in the young adult with mental retardation. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 34(1), 13–18. doi:10.5014/ajot.34.1.13

- Wilcock, A. A. (1998). An occupational perspective of health. Thorofare, NJ: Slack.