ABSTRACT

New Zealand’s political, civic, health and social institutions have been criticised as being ill-prepared to serve the health and social needs of the country’s increasingly diverse ageing population. This grounded theory study examined how late-life Asian immigrants participate in community to influence their subjective health. Bilingual Chinese, Indian, and Korean local intermediaries and research assistants were engaged as collaborative research partners. Purposive recruitment, and later theoretical sampling, were used to identify the 24 Chinese, 27 Indian, and 25 Korean participants, aged 60-83, who were 1-19 years post-immigration. Data were gathered through nine focus groups, and 15 individual interviews in the participants’ language of choice. All data were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and translated to English for analysis. Data analysis was done using open coding, constant comparative analysis and dimensional analysis. Strengthening community was the core social process in the substantive theory developed. The participants actively advanced cultural connectedness and gave service with, and for, each other. Over time, they extended their focus toward doing so for the wider community. They purposely used long-standing, occupation-related skills to resource how they and their co-ethnic groups contributed to community health. Additionally, they sought novel opportunities to diversify their contributions. These late-life immigrants intentionally strove to stay healthy through doing. Achieving collective, as well as personal, health through community participation was for the sake of minimising potential burdens on the country’s health system. The results indicate good health promotion policies would aim to advance co-ethnic, socially embedded networks for late-life Asian immigrants.

新西兰的政治,公民,卫生和社会机构被批评为没有做好充足的准备来满足该国日趋多元的老龄阶层的健康和社会需求。该基础理论研究检验了亚裔移民参与社区的方式如何影响他们的主观健康。当地双语华人、印度人和韩国人中介机构和研究助理作为研究合作伙伴而参与研究。被采用的入职招聘以及后来的理论抽样用来选定60-83岁的 24名中国人、27名印度人和25名韩国人作为研究参与者,他们已移民1至19年。通过9个焦点小组,及用参与者的选择语言进行的15次个人访谈收集数据。所有数据都记录下来,逐字录制,并翻译成英文以便进行分析。使用开放编码,恒定比较分析和同量级分析进行数据分析。加强社区是所发展的实质性理论的核心社会进程。参与者积极推进文化联系,为彼此服务。随着时间的推移,他们将重点放在更广泛的社区上。他们有目的地使用长期的与休闲有关的技能来帮助他们和他们的族裔群体为社区健康做出贡献。此外,他们寻求新的机会使其贡献多样化。这些晚年移民意图通过做事努力保持健康。通过社区参与实现集体和个人健康是为了尽量减少该国卫生系统的潜在负担。结果表明,良好的健康促进政策旨在加强为亚裔晚年移民所建立的多族群社会网络。

En Nueva Zelanda se han formulado críticas a las instituciones políticas, cívicas, sociales y de salud por ser inadecuadas para atender las necesidades sociales y sanitarias de una crecientemente diversa población que está envejeciendo. A partir de la teoría fundamentada, el presente estudio examinó cómo inmigrantes asiáticos de edad avanzada participan juntos para incidir en su salud subjetiva. Con este objetivo se contrataron varios intermediarios y asistentes de investigación chinos, indios y coreanos bilingües, de manera que fungieran como socios colaboradores en la investigación. Se llevó a cabo un reclutamiento deliberado y, más adelante, un muestreo teórico, para identificar a los participantes: 24 chinos, 27 indios y 25 coreanos, cuyas edades fluctúan entre 60 y 83 años, y cuya emigración se produjo en un periodo de hace 1 a 19 años. A partir de nueve grupos de enfoque y 15 entrevistas individuales realizadas en el idioma de preferencia del participante se recabó la información pertinente, que fue grabada, transcrita textualmente y traducida al inglés para su análisis. El análisis de datos se llevó a cabo utilizando la codificación abierta, el análisis comparativo constante y el análisis dimensional. El fortalecimiento de la comunidad constituyó el principal proceso social hallado en la teoría sustantiva desarrollada. En este sentido, los participantes promovieron activamente la conectividad cultural y, conjuntamente, se proporcionaron apoyo entre ellos. Con el tiempo extendieron sus apoyos a la comunidad más amplia. Para ello, utilizaron de manera deliberada antiguas habilidades ocupacionales que les permitieran potenciar su aporte —y el de sus grupos coétnicos— a la salud comunitaria. Estos migrantes de edad avanzada cuidaron su salud intencionalmente mediante su participación. La búsqueda de la salud colectiva y personal a través de la participación de los migrantes en la comunidad fue motivada por su deseo de minimizar la posible carga que pudieran representar para el sistema de salud de Nueva Zelanda. Estos hallazgos dan cuenta de que las políticas orientadas a promover la buena salud deben impulsar redes coétnicas e integradas socialmente, dirigidas a los inmigrantes asiáticos de edad avanzada.

The idea of communities being people, rather than being geographic regions (Marin & Wellman, Citation2016), maps well with occupational science. People, as community, relate through what they do to engage, support and provide services. Thinking about community in this way means social networks are enclaves of people “embedded in thick webs” (Borgatti, Mehra, Brass, & Labianca, Citation2009, p. 892) of social relating, and doing together. The embeddedness signifies that social networks “are rooted within and are emergent properties of social relations” (Kamath & Cowan, Citation2015, p. 723). Because socially embedded networks can function as bridges to cultural resources, and incubators of cultural identity (Mische, Citation2016), they may offer natural ways for immigrants, particularly late-life immigrants, to approach resettlement within a foreign culture. From an occupational science perspective, people’s participation in occupations that sustain desired traditions and lifeways is considered a prerequisite of health as well as a just society (Wilcock & Hocking, Citation2015).

Resettlement in unfamiliar social and cultural contexts influences late-life immigrants’ social embeddedness, including how they form and maintain social networks (Litwin, Citation1995). Consequently, recently arrived late-life immigrants to unfamiliar cultures are more likely than younger or long-term immigrants, and non-foreign-born migrants, to be socially isolated (Ikels, Citation1986; Warburton, Bartlett, & Rao, Citation2009) and lonely (Treas & Mazumdar, Citation2002). Limited proficiency in the host country’s dominant language may be a significant reason late-life immigrants are less incorporated within wider societal relationships (Diwan, Citation2008). Supporting this argument, older Indian immigrants in the US (Mukherjee & Diwan, Citation2016), and Chinese immigrants in New Zealand (Abbott et al., Citation2003; Selvarajah, Citation2004) relied on family and socially embedded relationships. In Selvarajah’s study, for the third of the study sample (n=105) who indicated an intention to reside permanently in the country, there was a statistically significant association with their engagement with, and embeddedness within, their co-ethnic social networks. Similarly, older Korean immigrants in two US cities, who were embedded in social networks including family and neighbourhood groups, were significantly more likely to rate their health positively and report fewer depressive symptoms than those who were not (Park, Jang, Lee, & Chiriboga, Citation2017).

There is a growing body of evidence that late-life immigration from a culturally and linguistically different background can contribute negatively to health and wellness. The risks to wellness include mental health problems, such as depressive symptoms (Abbott et al., Citation2003), and culture-specific psychological symptoms (Tummala-Narra, Sathasivam-Rueckert, & Sundaram, Citation2013). It seems that any immigrant health advantage, observed when good migrant health is a host-country pre-requisite, is off-set by evidence of late-life immigrants’ risks for a rapid decline in health, the longer they stay in the host country (Rote & Markides, Citation2014). In essence, people’s age and migration history (Shin, Han, & Kim, Citation2007), including the countries of origin and destination, and duration of resettlement, intersect to shape late-life immigrants’ well-being, and may act to systematically disadvantage them (Dwyer & Papadimitriou, Citation2006). However, strong relationships within socially embedded networks seem to be an important mediator for late-life immigrants’ psychological well-being. For example, “regardless of the level of acculturative stress” (Han, Kim, Lee, Pistulka, & Kim, Citation2007, p. 117), older Korean immigrants’ low depression scores have been associated with more extensive social networks and more satisfying supportive social relationships. Likewise, over time, Korean immigrants with highly supportive social relationships were protected against the negative impacts and psychological distress caused by late-life settlement in Southern California (Min, Moon, & Lubben, Citation2005).

Such results are consistent with evidence from a qualitative study with older Indian immigrants recruited from an Indian seniors’ community programme (Tummala-Narra et al., Citation2013). Their stories revealed that participation in socially embedded, co-ethnic networks helped them cope with cultural changes, isolation, and loneliness (Tummala-Narra et al., Citation2013). In accord, older transnational immigrants, either on extended family visits or permanently resettled in California, were lonelier and more dissatisfied when isolated from engaging socially beyond their kin networks (Treas & Mazumdar, Citation2002).

One criticism of ethnic enclaves of socially embedded networks is they hinder late-life immigrants’ incorporation, or assimilation, into the new host society. Yet, the overwhelming evidence indicates late-life immigrants’ embeddedness in co-ethnic social networks is worth promoting. High-density immigrant neighbourhoods and community organisations that enable social relating, and the establishment of social networks, seem to provide a structural foundation for older immigrants’ social embeddedness (Cook, Citation2010; Rote & Markides, Citation2014). Supporting this notion, doing culturally meaningful occupations embedded in ethnic community cultural, and/or religious, organisations improved older Indian immigrants’ health and well-being (Diwan, Citation2008) and quality of life (Mukherjee & Diwan, Citation2016), and older Korean immigrants’ happiness, social connections, and psychosocial well-being (Kim, Kim, Han, & Chin Citation2015). Furthermore, the nature of the relationships and embeddedness in church-centred activities were more important for older Chinese immigrants’ feeling of belonging than was the duration of involvement in the Chinese church community in a southern US state (Liou & Shenk, Citation2016). Cook (Citation2010) described co-ethnic social networks, enabled through community centres, as providing “places of shared language, interests and culturally appropriate and intimate support” (p. 267) for older immigrant women in the UK. One of the older Chinese immigrants was emphatic “that creating a space for Chinese women to come together and support each other was the best way of addressing the needs and preferences of Chinese women” (Cook, Citation2010, p. 269). Such evidence suggests the social relevance of understanding how and why late-life immigrants engage in groups as a way of helping themselves and volunteering time to help others in similar circumstances as themselves.

Evidence supporting participation in informal, ethnic-based social programmes, rather than publicly available mainstream programmes has a long history, dating from a study of older Asian and Latin American immigrants in Boston in the 1960s (Ikels, Citation1986). Furthermore, members of their co-ethnic social networks functioned as outreach workers; locating and connecting with those who were unable to or uncomfortable with engaging in the unfamiliar sociocultural context. In this way, it was the co-ethnic, non-familial helpers who enabled other late-life immigrants’ resettlement (Ikels, Citation1986). The results of this earlier study lend credence to Eckstein’s (Citation2001) description of collectivistic-based volunteering as participation that “involves acts of generosity that groups (rather than individuals) initiate, inspire, and oversee; individuals participate because of their group ties” (p. 829). More recent evidence comes from a Florida-based, longitudinal study of successful ageing for the general older adult population, aged 80 years on average at baseline (Kahana, Bhatta, Lovegreen, Kahana, & Midlarsky, Citation2013). It examined how well altruistic attitudes, volunteering frequency, and informal helping activities predicted life satisfaction, positive and negative affect, and depressive symptoms, over 3 years. Participants’ “volunteering was the most consistent predictor of the well-being outcomes” (Kahana et al., Citation2013, p. 179). Interestingly, the results revealed altruism, or holding a spirit of generosity, was positively associated with the older adults’ positive emotions, independent of their capacity to function as a helper. Consistent with the late-life immigrant research, the beneficial social relations were embedded within the volunteering social networks.

While the literature demonstrates the positive influence late-life immigrants’ participation in co-ethnic, socially embedded networks groups has on personal and collective well-being, there is a gap in understanding how this occurs. Therefore, this New Zealand study examined how late-life Asian immigrants participate in community, with a particular focus on understanding how they used their participation to positively influence their subjective health. The somewhat unique New Zealand context is considered as a further justification for the study.

Context of this Study

Ethnically, New Zealand is superdiverse. As a country, it exceeds the internationally recognised superdiversity threshold of over 100 nationalities represented and immigrants constituting at least a quarter of the resident population (Chen, Citation2015). At the time of the last national census, the number of ethnic groups identified outnumbered the world’s countries (Statistics New Zealand, Citation2013a) within a national population of about 4.5 million people (Statistics New Zealand, Citation2014). In accord, a defining feature of Auckland, the country’s largest city, is its ethnic superdiversity, with 44% of its population being born outside New Zealand (Chen, Citation2015), and Asian peoples constituting about 23% of the city’s population (Massey University, Citation2015). The country’s Asian population is projected to reach 1.26 million in 2038, up from 0.54 million in 2013, with the number of people identifying as Asian expected to exceed those identifying as Māori, New Zealand’s indigenous peoples (Statistics New Zealand, Citation2015). Moreover, the Asian population itself is ageing.

In 2013, Asian peoples aged 65 years and over constituted just under 6% of the country’s Asian population; a proportion projected to increase to 14.6% in 2038. Some of this growth will come from Asian peoples ageing in New Zealand, but some came from a significant increase in late-life immigrants, particularly from Asia, who joined their non-dependent adult children under the Parent or Parent Retirement Categories for family reunification (Immigration New Zealand, Citation2014) before they were suspended at the end of 2016. The largest numbers of late-life Asian immigrants arrived from China, India, and South Korea. The 2013 Census of Population and Dwellings (Statistics New Zealand, Citation2013b) reported a population of at least 6,147, made up of Chinese (3,657), Indian (2,253), and Korean (237) immigrants, aged 60 and over, settled in New Zealand. Their duration since arrival ranged from less than 1 year to 20 years. Within this demographic, those aged 60–69 years constituted the largest late-life cohort at 2,955, comprising Chinese (1,869); Indian (1,026); and Korean (60) immigrants. Those aged 70–84 in 2013 constituted the next largest demographic cohort at 1,515; 1089; and 126 respectively. Those aged 85 years and over made up the smallest cohort at 273; 138; and 51 respectively. The pattern is relatively consistent across each cohort, with just under two thirds being Chinese, about one third Indian, and the remainder being Korean late-life immigrants. A beginning point for New Zealand being socially inclusive would be a familiarity with Asian people’s experiences, understandings, and expectations for ageing well in New Zealand (Butcher, Citation2010).

Research Design

Because the research aimed to explain the process by which late-life immigrants went about contributing to community, a Strausserian grounded theory methodology was chosen. It guided the research methods for recruitment, data gathering, and data analysis. As such, the research sought to develop a substantive theory on how participating in community, a fundamental social process, may influence late-life immigrants’ health. An overview of the resulting theory, with a focus on late-life immigrants’ cultural enfranchisement through co-ethnic participation, has been previously published (Wright-St Clair & Nayar, Citation2017).

Being monolingual in English, the researchers established a partnership approach to achieve cultural relevance of the research design and methods. Initial consultation with, and support from, a Ministry of Social Development Community Relations Manager facilitated referral to bilingual Chinese, Indian, and Korean intermediaries who were active with local older immigrant groups. These intermediaries supported the project and assisted with its design and implementation. Subsequently, native-speaking, bilingual research assistants and interview transcript translators were appointed to the project team. Ethics approval was granted by the Auckland University of Technology Ethics Committee. Written and verbal information about the study was provided in potential participants’ language of choice. All participants consented in writing. Participant confidentiality was respected by way of using participants’ self-selected pseudonyms and ensuring transcribers and translators signed confidentiality agreements.

Recruitment and participants

Inclusion criteria were agreed to be immigrants aged 60 years or older, self-identifying as Chinese, Korean, or Indian, aged 55 years or over on arrival, and resident in New Zealand for at least 6 months. Recruitment was initiated by placing native language-specific flyers in community and church halls where older immigrant ethnic groups were held. Further to this, the researchers, in partnership with the local intermediaries, attended relevant ethnic community gatherings to explain the study and answer questions. Seventy-six participants volunteered; 24 Chinese (11 men & 13 women), 27 Indian (17 men & 10 women), and 25 Korean (12 men & 13 women) late-life immigrants, aged 60 to 83 years, who had resided in New Zealand for 1 to 19 years. The Chinese and Korean participants had limited or no conversational English, while the Indian participants spoke conversational English overlaid with some Hindi.

Data gathering

Data were initially gathered through nine ethnic-specific focus groups, three (men-only, women-only, and mixed gender) within each community, in the participants’ language of choice. Questions were designed to understand what participants did and how they strategised to participate in community. For example, focus group participants were invited to share “what you do in the community” and “tell us about how you participate in your community.” Probing questions such as “Do others feel the same?” were used to gather a range of views, and “can you say a little bit more about the volunteer work?” to add understanding and context. Individual interview questions encouraged greater depth, such as “you mentioned about starting to feel depressed or sad with working with people who had disabilities. How do you think your health has been affected through your participation?”

Data analysis

The focus group recordings were transcribed verbatim and translated into English for analysis using grounded theory methods of open coding, memo writing, and constant comparison of the data (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998). Both researchers (VW and SN) independently undertook open coding for the focus group transcripts. Once completed, the researchers met to compare and discuss the codes. Once consensus was reached, SN proceeded with a constant comparison of the data drawing on Schatzman’s (Citation1991) dimensional analysis framework. At this stage three provisional, culture-specific theories were conceptualised.

As the ethnic-specific theorising developed, theoretical sampling of selected focus group participants was conducted for individual interview. One or both of the researchers (VW and/or SN) were present for each interview to assist and support the native-speaking interviewer. Each researcher wrote memos following each interview attended. Memos were uploaded to a password protected cloud database for ease of access. The transcribed, translated, data from 15 individual interviews, five within each ethnic group, were used to refine the concepts and categories across the three emergent, ethnic-specific theories, to develop one cross-cultural dimensional matrix that captured the participation aspects and processes for all participants across the provisional theories (Berry, Citation1989). Again, both researchers independently completed open coding on the translated transcripts. SN conducted the constant comparison of data and drafted the results. VW reviewed the results and discussed points of agreement and disagreement with SN. The final results were reached by consensus agreement. According to Berry, deriving an etic theory from the emic, or culture-specific data, is valid when emic data across the groups hold deep similarities. Member-checking was conducted by sending participants a written summary of results translated into their own language, and through translator-facilitated community meetings for each ethnic community, giving participants opportunities to discuss, and comment on, the results.

Results

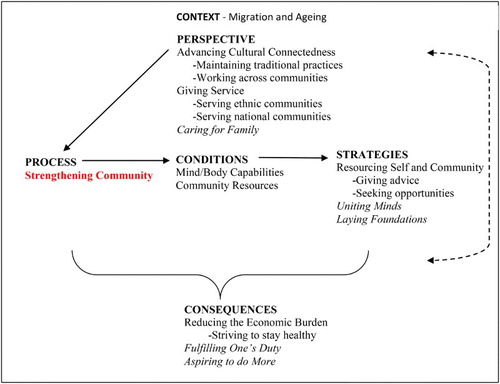

This paper presents the substantive, cross-cultural theory of how late-life Chinese, Indian, and Korean immigrants participate in community, with a focus on examining how participation influences subjective health. displays the substantive theory, with a particular focus on the results related to how the participants managed their own and others’ wellness through contributing to their socially embedded networks. Italicised text is used for direct participant quotes and title case for named components of the substantive theory developed.

Figure 1. The substantive theory. Key: Components of the substantive theory that were not represented in this paper on how participation influenced subjective health are indicated in italics.

The societal context

The New Zealand societal context, for the late-life Asian immigrants participating in this study, is vastly different from the societies they left behind in China, India, and South Korea, respectively. Thus ageing, at the same time as resettling in the host environment, presents situations that were potentially unforeseen by these late-life immigrants. That is, the embodied changes that come with the natural ageing processes occur at the same time they encounter new environmental, political, and sociocultural challenges. For example, Laura (Chinese), aged 75, mentioned, “we must fit into this surrounding by ourselves”. As a situated process, ageing as an international immigrant is a circumstance of an altered life trajectory. Peter’s (Korean) quote is informative on context:

As we [my wife and I] left Korea, our memory also stopped. [In our memories] We stay still the same as 20 or 30 years ago … . So I want us to think outside of the box. I started playing table tennis since I came here. I can play it now. My brain is much slower than before but I can still move my body. If there is only a place, we can do many things.

Life perspectives

As participants talked about participating within their neighbourhoods, their co-ethnic communities, and civic society, two perspectives regarding how they participated emerged: ‘Advancing Cultural Connectedness,’ and ‘Giving Service.’ To explain the perspective of Advancing Cultural Connectedness; these late-life immigrants were mindful of living in a country comprised of multiple, diverse, and what sometimes felt like competing cultures. Their awareness fuelled an eagerness for ‘Maintaining traditional practices’ from their homeland, in order to retain what they could of their historically-familiar traditions. Kiran’s (Indian) outlook, at age 82, was toward his grandchildren knowing the Indian traditions. In reality, he viewed it as “the duty of the older generation [to] imbibe into them our customs and culture”, in the hope traditional knowledge and ways will be passed on and continued. Joyce’s (Korean) quote shows she migrated to New Zealand already holding a view of maintaining traditional Korean practices in the host country:

When I came to New Zealand, I transported all the instruments for Samulnori, Korean traditional percussion quartet … . Every year, many of the [international Korean] students I hosted performed Samulnori, but they didn’t have any traditional clothes and staffs; so I made them all.

For my personal hope, I think it would be better if we can be given opportunity to meet people from other countries and share personal and individual talk, so that we can talk face to face and communicate deeply.

The perspective of Giving Service was heard across the Chinese, Indian, and Korean participant focus groups, as well as the individual interviews. Participants’ perspective was outward-looking, of serving the greater good. Giving Service was evident in Kish (Indian) suggesting “together, we should help each other”; and Sam (Chinese) advocating, as late-life immigrants:

We should make some contributions to societies. Even horses and cattle contribute by pulling carts. Without contribution you are just the same as pigs. So I think we must find ways to contribute to the society, do whatever we can.

I lived near the Chinese supermarket, so I always bring the free Chinese newspapers for those people who are hard to access to them.

If we get an opportunity [to volunteer], any time; but in this society it works both ways. When we beg for the work they don’t give us, but if they call us, we go out of the way and do it. (Jaggu, Indian)

I have a volunteer work at the Welfare Centre before. I met new Korean couple there. When I met them, I felt that they are very happy people, [but] their life was just for breathing. They have many kinds of diseases, such as, limping, headache … some senior members visit there together. When we visit them, we pack some snacks and give it to each house … .Through this volunteer work, we can show others that we can be a help (Joanna, Korean)

Based on the dance skills we have learnt, we often organise performances in rest homes … These old ladies are happy for our performances. We always take photos together after the performances … Almost all activities, which aim to contribute into society, are organised via this [Chinese] Association. So the [Chinese] communities play an important role. (Hehm, Chinese)

These late-life Asian immigrants’ life perspectives were generous in their intent, and generative toward promoting subjective health through building community strengths.

Strengthening community as process and purpose

The core social process explaining how the late-life Asian immigrants in this study participated, is ‘Strengthening Community.’ For many of these participants, the social, and environmental foundations for enabling strong ethnic communities were already in place; established by co-ethnic members, and late-life immigrants, who came before them. What the data showed is how they acted deliberately and strategically, to consolidate and extend opportunities for co-ethnic and wider community participation for the express purpose of optimising health and well-being. In particular, the participants’ ‘Mind/Body Capabilities’, and their strategies for resourcing themselves and their communities are explained, as they relate to augmenting wellness as well as overcoming post-immigration states, such as loneliness and depression.

The participants acknowledged an awareness of their Mind/Body Capabilities influencing what they did, and how they participated in community. Their embodied capacities were a complex mix of participation skills interacting with ageing and functional changes. As late-life immigrants, they brought many skills into the host society as products of earlier careers and leisure interests, such as engineering, accounting, managing, teaching, traditional dancing, tai chi, sports, table tennis, choral singing, traditional cooking, calligraphy, and using herbal remedies, to name a few. On the other hand, diminishing capacities such as “eye problems” and “hearing problems”, along with “not driving”, “not speaking English” and “loneliness” potentially limited participation. Nonetheless, numerous examples were given in which existing skills and capacities were utilised in the new social context, for example Mike (Chinese) mentioned “I play Tai Chi and sing in the Chinese Organisation because of my hobbies. I liked sports and singing when I was in China”. Others’ recollection of accessing co-ethnic ‘Community Resources’ demonstrated their collective health worth, such as Michelle’s (Korean) account:

If I do not have activities like nowadays, I will be so depressed. If we stay alone for a long time, it feels like we are sinking into swamp; but by doing activities I feel free from depression. Every morning, the thought I am going somewhere makes me very busy. I wake up, wash, put on makeup, worry about what to wear, and meet friends. Some associations teach us to move through dancing and practices. They are funny and healthy.

I prefer dynamic activities, such as Tai Chi and dancing. They had these activities [at the Chinese association]; however, they were not familiar to me at that time … , [Now] I still go when get ill. Several times I brought a walking stick and still taught them dance.

I am a registered volunteer at Auckland [outreach] library … I deliver them [people at home] the books, take the books from them to the library. But my handicap is, I don’t know driving. So what I told them is, I go to the people who are within walking distance.

Given the conditions these late-life Asian immigrants were experiencing, the strategy of ‘Resourcing Self and Community’ is grounded in the data describing how they went about optimising others’, as well as their own, health and well-being. Their tactics fell under two predominant sub-categories, ‘Giving advice’ and ‘Seeking opportunities’. In Giving advice, these senior immigrants counselled fellow co-ethnic immigrants on ways to build health and well-being capabilities. For example, Kish (Indian) advised his wife to “just keeping moving and active. Otherwise at home what she will do is knitting, knitting all the time sitting here, so better just go out and move”. In his community, Xiao Mao (Chinese) said he “always advises people to participate in our [Chinese association] activities”, because he observed “some Chinese never go out … there is no social contact with others. I don’t think it is a good way. It is not beneficial for our health”. In reciprocity, there were times when wise counsel was received.

Alongside Giving advice, and receiving it, Seeking opportunities to participate in community were enacted through creating new, and pursuing existing, ways of engaging. For example, Joanna (Korean) described how her female cohort of older Korean immigrants came to set up a knitting group:

We found out that even though young people want to have knit sweater or vest, they do not have time and skill to knit. So we told them we will knit for them. It is good that we seniors serve others … . So we appointed her [Michelle] as a leader and we all together knit sweaters or vests for young people.

In the park, I found most of the old people felt sad … . So we decided to exercise together. We studied on Saturday, and exercised on Tuesday. Then we established an elderly fitness team on July 8th, 1997. After that … we further established the Central Chinese organisation … . Our organisation is very helpful for those people who came to this country at a late stage [of life].

The consequence of reducing the economic burden

Consequence is theorised in this study as the effect of late-life immigrants’ community participation. Rather than leaving things to chance, the data suggest these late-life immigrants acted to galvanise a main desired outcome of ‘Reducing the Economic Burden’ for the Government by positively influencing their own and others’ health. They were mindful of public opinions, voiced through the mass media, criticising late-life immigrants for being a drain on the economy (Small, Citation2013). Further, they were cognisant of receiving social benefits, in spite of being late-life immigrants, and expressed a “keen desire to contribute, and to pay back to whatever we are getting from the Government in this highly welfare State” (Gaurav, Indian). One frequently-mentioned way of giving back was through helping raise grandchildren, while supporting adult children so they “could concentrate on their work and create wealth for New Zealand” (Hui, Chinese). By (Chinese) elaborated further:

At first my son worked at night and studied during the daytime. Therefore, during these 9 years I supported him; my major task was cooking, preparing healthy food for him, and I did all the household work. Now, after he got the Master’s degree in computing and software, he owns his office room. I think it is beneficial for New Zealand. So I think it is my biggest contribution.

Participating in ways that benefitted the wellness of the co-ethnic and/or wider community was another vital way of giving back, thereby lessening the “burden to the Government, to the health department, because we are contributing” (Anubandh, Indian). Sally (Korean), who did “volunteer work at [the local] Welfare Centre”, explained it this way:

All people there are sick … . Our pastor, some young children who can play musical instruments, and some senior members visit there together.

Furthermore, participating in co-ethnic communities affected the common personal and collective aim of ‘Striving to stay healthy’ as a way of Reducing the Economic Burden. As Gaurav (Indian) explained in one of the focus groups; “in fact my first target is to take care of my health. That is why, the first aim is to ensure that we remain healthy”. Ram (Indian) emphasised how contributing to community affords “mental satisfaction and happiness”. Others in the group added: “If you help someone you feel happy, I feel like that is so” (Sita). “If you do good to others, you do good to yourself” (Ram), in other words, “you’re passing your time gainfully” (Mohammed). “This is the main thing, if you can, you should help your community. It’s great and working with older people, if you give them a little happiness, you get more, more happiness to your heart. And that is the thing to keep you healthy” (Fatema).

Discussion

This study examined how late-life Chinese, Indian, and Korean immigrants in New Zealand participate in community, with a particular focus on exploring how their participation might influence subjective health. It was evident that later-life ageing amidst an unfamiliar cultural context exposed these participants to unforeseen life challenges and opportunities. The occupational circumstances faced exposed the importance of ‘thinking outside the box’ to engage in new ways within a Westernised society. Yet, their fundamental life perspectives were strengthened. As was evident from the data, these late-life immigrants found purpose in advancing connectedness, primarily within family and co-ethnic communities, by being of service in whatever way they could. They were wholehearted in contributing for others’ benefits, a quality that aligns with Ikels’ (1986) observation of older immigrants’ sincere beliefs “in the value of helping” (p. 219). Volunteering seemed to be a natural way of participating in their communities. It has been purported that older adults, in general, are ‘natural helpers;’ contributing to “a massive unregulated social welfare system” (Goodman, Citation1984, p. 138), theorised as a social exchange in which benefits are reciprocal. In line with this, social involvement through volunteering has been proposed as an occupationally situated prerequisite of health (Wilcock & Hocking, Citation2015). Certainly, this study’s findings exposed extensive, co-ethnic, socially embedded networks through which participants gave and received culturally-situated social and health benefits.

Older immigrants being natural helpers toward other older immigrants is consistent with previous studies (Cook, Citation2010; Ikels, Citation1986). Similar to Ikels’ findings, the participants in this study talked about the natural practice of introducing newcomers to existing co-ethnic community occupations. Engaging through co-ethnic social networks became a natural stepping-stone to contributing to the welfare of people and disadvantaged groups within wider society. Yet, at the same time as being others’ natural helpers, these late-life Asian immigrants acted wilfully towards their own health and wellness gains.

Objective health data were not gathered in this study, however, participants emphasised their subjective health and wellness gains through doing things which strengthened communities. That is, through helping, and adding to others’ happiness, particularly through engaging with their co-ethnic cohorts, these late-life Asian immigrants described improvements for their own health and wellness. Of significance to this study’s results, self-assessed health and functional capacities have been shown to be important indicators of older Korean immigrants’ psychological distress over time (Min et al., Citation2005). Nonetheless, civic engagement through volunteering has been shown to be a significant influence for retirees, in general, feeling positive and experiencing fewer depressive symptoms (Kahana et al., Citation2013). While this New Zealand study did not aim to identify how their health and wellness risks and/or gains might differ from non-immigrants’, or other non-Asian immigrants’, the participants talked frequently about developing deliberate strategies in order to find opportunities to participate in an unfamiliar society. Their unique, yet shared context, demanded developing new skills, in addition to finding creative ways of using their long-standing skills in ways they had not anticipated prior to immigration. In support of this argument, research has demonstrated immigration in later-life “clearly impacts on the formation and maintenance of social ties” (Litwin, Citation1995, p. 171) and influences “differently constituted life-worlds” (Gronseth, Citation2013, p. 2) in which community participation becomes a blend of familiar fragments of pre-immigration lives, while at the same time being confronted with markedly unfamiliar practices.

In contrast, however, none of the four social networks Litwin (Citation1995) defined – family intensive, kin, friend focused, and diffuse tie networks – align with the social, community contribution networks this study’s late-life immigrants described. It was evident these late-life immigrants sought out, and participated in, occupations in their co-ethnic communities to positively influence their own, and others’ physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being. As posited by Wilcock and Hocking (Citation2015), their positive health was served through doing things that offered “meaning, choice, satisfaction, a sense of belonging, purpose, and achievement” (p. 172). Striving to stay healthy, personally and collectively as late-life immigrants, was a central finding. It perhaps lends support to Gronseth’s (Citation2013) interpretation of an essential human quality in the “shared quest for well-being” (p. 9).

This study seems to contribute two dimensions of unique knowledge to the occupational science and immigration fields. Firstly, the participants’ explicitly aimed to reduce the potential economic burden of their immigration in later-life through their chosen, volunteering occupations. Hence, they acted strategically to confer indirect benefits to the health and social welfare sectors. Secondly, it was evident further subjective health and happiness gains were achieved through contributing to others’ healthfulness and happiness through what they did with and for their socially embedded networks. Consequently, through their participation they invested themselves into strengthening their co-ethnic, and often wider social communities. Socio-politically, the findings of this study endorse Cook’s (Citation2010) recommendation for publicly resourcing older immigrants’ informal networks to “enable older migrants collectively ‘to provide for themselves’” (p. 270). In other words, the participants engaged in their own form of occupationally situated social action. They found belonging by doing with others like them, they were energized by the purpose of what they did, and they contributed positively to the circumstances that helped serve their collective primary health (Wilcock & Hocking, Citation2015).

Limitations

This study has two primary limitations. Firstly, the participants were recruited through established co-ethnic community groups. This means this theory of how late-life Chinese, Indian, and Korean immigrants contribute to community cannot claim to represent how more socially isolated late-life Asian immigrants participate. However, many of the participants gave spontaneous accounts of having been socially isolated after immigration, and of knowing other co-ethnics who tend to remain within the home. The data showed these participants understood, from personal experience, the harms of social isolation. Hence, they personally and collectively sought creative ways to locate isolated co-ethnics and devised ways of advancing cultural connections. Secondly, no back-translation of the English translations was done. This limitation was partly addressed by providing participants with a translated summary of the study results, including ethnic specific and cross-cultural theories, in print and via co-ethnic group meetings. No changes were made as a consequence of the community feedback process.

Further research ought to test the substantive cross-cultural theory with other large Asian late-life immigrant populations, such as Filipinos, and smaller populations such as Nepalese. Comparative research could examine how the processes differ for late-life immigrants from Western, colonised countries such as Australia, Canada, and the United States of America.

Conclusion

These 76 late-life Chinese, Indian and Korean immigrants strategically chose ways of participating in community that supported their subjective health. They made deliberate choices about what occupations they would do as late-life immigrants in an unfamiliar context, and how they would do them. They often mentioned an increased awareness of what contributed negatively to their health in the host environment as the impetus for finding new ways of participating. Sitting at home, not being physically active, being culturally and linguistically isolated, and feeling lonely, were mentioned as reasons to strive to stay healthy.

How these participants went about gaining healthfulness included physical leisure participation, such as doing tai chi and traditional performance, socio-cultural participation like teaching traditional languages and handicrafts, and community volunteering such as helping at a homeless shelter and delivering library books, to name a few. They talked about learning new skills, such as knitting and dancing, in order to participate in community when their long-standing occupational repertoires from the homeland did not serve the purpose. Consistent with the literature, engaging with co-ethnic communities was the primary mechanism these late-life Asian immigrants used to participate in community. Participation was about striving to stay physically and emotionally healthy. As a consequence, this study contributes empirical evidence to theorising an occupational perspective of health for an underserved sector of the New Zealand population.

Auckland’s established Chinese, Indian, and Korean populations of late-life immigrants offered most the opportunity to participate through long-established, co-ethnic community groups. Yet it was evident some were prepared to initiate new affiliations where a personal or collective health need presented itself. They were prepared to do whatever they could, as staying healthy mattered to them. Interestingly, participating to stay healthy was done indirectly. That is, by participating in ways that served others’ happiness and health, primarily in their co-ethnic socially embedded networks, these late-life immigrants benefitted their own health. In this way community participation served a dual subjective health benefit. At the same time, a broader moral aim was evident. Participating to stay healthy meant these late-life immigrants acted to minimise the burden on the country’s health system.

The social process of strengthening community is at the core of this theory of how late-life immigrants used participation for collective and personal health. The results imply that mainstream community, health and social services will not be the vehicle of first choice for late-life Asian immigrants in New Zealand to achieve health gains. Rather, they indicate public strategies that connect established and arriving late-life immigrants within co-ethnic social networks should be advanced. Such strategies would aim to promote late-life immigrants’ subjective individual and community health through helping each other.

Declaration of Contribution of Authors

The first two authors (VW & SN) contributed equally to the community engagement, the study design, and execution of the project. The second author (SN) contributed significantly to the grounded theory method of data analysis. The first author (VW) contributed significantly to writing this article. All other authors (HK, SW, SS, JS, CH, AC) contributed to community engagement and execution of the project, and to manuscript revisions.

Acknowledgements

Mr Murali Kumar, Relationship Manager Community Relations, Ministry of Social Development is acknowledged for his support through first contact with the Chinese, Indian, and Korean local intermediaries.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no financial, personal or other conflicts of interest to declare.

ORCID

Valerie A. Wright-St Clair http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7505-3946

Shoba Nayar http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9777-5915

Hagyun Kim http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4705-5549

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abbott, M. W., Wong, S., Giles, L. C., Wong, S., Young, W., & Au, M. (2003). Depression in older Chinese migrants to Auckland. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 37(4), 445–451. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2003.01212.x

- Berry, J. W. (1989). Imposed etic-emics-derived etics: The operationalization of a compelling idea. International Journal of Psychology, 24(6), 721–735. doi:10.1080/00207598908247841 doi: 10.1080/00207598908246808

- Borgatti, S. P., Mehra, A., Brass, D. J., & Labianca, G. (2009). Network analysis in the social sciences. Science, 323(5916), 892–895. doi: 10.1126/science.1165821

- Butcher, A. (2010). Demography, diaspora and diplomacy: New Zealand’s Asian challenges. New Zealand Population Review, 36, 137–157.

- Chen, M. (2015). Superdiversity stocktake: Implications for business, government & New Zealand. Auckland, New Zealand: Superdiversity Centre.

- Cook, J. (2010). Exploring older women’s citizenship: Understanding the impact of migration in later life. Ageing & Society, 30(2), 253–273. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X09990195

- Diwan, S. (2008). Limited English proficiency, social network characteristics, and depressive symptoms among older immigrants. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 63B(3), S184–S191. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.3.S184

- Dwyer, P., & Papadimitriou, D. (2006). The social security rights of older international migrants in the European Union. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 32(8), 1301–1319. doi: 10.1080/13691830600927773

- Eckstein, S. (2001). Community as gift-giving: Collectivistic roots of volunteerism. American Sociological Review, 66(6), 829–851. doi: 10.2307/3088875

- Goodman, C. C. (1984). Natural helping among older adults. The Gerontologist, 24(2), 138–143. doi: 10.1093/geront/24.2.138

- Gronseth, A. S. (2013). Introduction: Being human, being migrant: Senses of self and well-being. In A. S. Gronseth (Ed.), Being human, being migrant: Senses of self and well-being (pp. 1–26). New York, NY: Berghahn Books.

- Han, H.-R., Kim, M., Lee, H. B., Pistulka, G., & Kim, K. B. (2007). Correlates of depression in the Korean American elderly: Focusing on personal resources of social support. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 22(1), 115–127. doi:10.1007/s10823–006–9022–2 doi: 10.1007/s10823-006-9022-2

- Ikels, C. (1986). Older immigrants and natural helpers. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 1(2), 209–222. doi: 10.1007/BF00116045

- Immigration New Zealand. (2014, 7 April 2014). Live: Parent Retirement Category. Retrieved 19 February, 2016, from http://www.immigration.govt.nz/migrant/stream/live/parentretirementcategory/

- Kahana, E., Bhatta, T., Lovegreen, L. D., Kahana, B., & Midlarsky, E. (2013). Altruism, helping, and volunteering: Pathways to well-being in late life. Journal of Aging and Health, 25(1), 159–187. doi: 10.1177/0898264312469665

- Kamath, A., & Cowan, R. (2015). Social cohesion and knowledge diffusion: Understanding the embeddedness-homophily association. Socio-Economic Review, 13(4), 723–746. doi: 10.1093/ser/mwu024

- Kim, J., Kim, M., Han, A., & Chin, S. (2015). The importance of culturally meaningful activity for health benefits among older Korean immigrants living in the United States. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being, 10(27501), eCollection. doi:10.3402/qhw.v10.27501

- Liou, C.-L., & Shenk, D. (2016). A case study of exploring older Chinese immigrants’ social support within a Chinese church community in the United States. Journal of Cross-cultural Gerontology, 31(3), 293–309. doi: 10.1007/s10823-016-9292-2

- Litwin, H. (1995). The social networks of elderly immtgrants: An analytic typology. Journal of Aging Studies, 9(2), 155–174. doi: 10.1016/0890-4065(95)90009-8

- Marin, A., & Wellman, B. (2016). Social network analysis: An introduction. In J. Scott & P. J. Carrington (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of social network analysis (pp. 11–25). London, UK: Sage.

- Massey University. (2015, 24 April 2015). Political parties need to embrace ‘super-diversity’. Retrieved 19 February 2016, from http://www.massey.ac.nz/massey/about-massey/news/article.cfm?mnarticle_uuid=1E27606A-CA5C-9A61-06BA-1D96F4285A37

- Min, J. W., Moon, A., & Lubben, J. E. (2005). Determinants of psychological distress over time among older Korean immigrants and Non-Hispanic white elders: Evidence from a two-wave panel study. Aging & Mental Health, 9(3), 210–222. doi: 10.1080/13607860500090011

- Mische, A. (2016). Relational sociology, culture, and agency. In J. Scott & P. J. Carrington (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of social network analysis (pp. 80–98). London, UK: Sage.

- Mukherjee, A. J., & Diwan, S. (2016). Late life immigrations and quality of life among Asian Indian older adults. Journal of Cross-cultural Gerontology, 31(3), 237–253. doi: 10.1007/s10823-016-9294-0

- Park, N. S., Jang, Y., Lee, B. S., & Chiriboga, D. A. (2017). The relation between living alone and depressive symptoms in older Korean Americans: Do feelings of loneliness mediate? Aging & Mental Health, 21(3), 1–9. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1099035

- Rote, S., & Markides, K. S. (2014). Aging, social relationships, and health among older immigrants. Generations, 38(1), 51–57.

- Schatzman, L. (1991). Dimensional analysis: Notes on an alternative approach to the grounding of theory in qualitative research. In D. R. Maines (Ed.), Social organizations and social process: Essays in honour of Anselm Strauss (pp. 303–314). New York, NY: Aldine Guyter.

- Selvarajah, C. (2004). Expatriation experiences of Chinese immigrants in New Zealand. Management Research News, 27(8/9), 26–45. doi: 10.1108/01409170410784626

- Shin, H. S., Han, H.-R., & Kim, M. T. (2007). Predictors of psychological well-being amongst Korean immigrants to the United States: A structured interview survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 44(3), 415–426. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.04.007

- Small, V. (2013, 24 May). Peters: Immigrants, brothels and sin city. Stuff. Retrieved from http://www.stuff.co.nz/national/politics/8714017/Peters-Immigrants-brothels-and-sin-city

- Statistics New Zealand. (2013a). New Zealand has more ethnicities than the world has countries. Retrieved 19 August 2017, from Statistics New Zealand http://www.stats.govt.nz/Census/2013-census/data-tables/totals-by-topic-mr1.aspx

- Statistics New Zealand. (2013b). 2013 Census of population and dwellings: Age group and years since arrival in New Zealand by ethnic group [Special report JOB-06846]. Wellington: Statistics New Zealand.

- Statistics New Zealand. (2014). National population projections: 2014(base)–2068. Retrieved 19 February 2016, from http://www.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/population/estimates_and_projections/NationalPopulationProjections_HOTP2014.aspx

- Statistics New Zealand. (2015). National ethnic population projections: 2013(base)-2068. Retrieved 19 February 2016, from http://www.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/population/estimates_and_projections/NationalEthnicPopulationProjections_HOTP2013-38.aspx

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.). London, UK: Sage.

- Treas, J., & Mazumdar, S. (2002). Older people in America’s immigrant families: Dilemmas of dependence, integration, and isolation. Journal of Aging Studies, 16(3), 243–258. doi: 10.1016/S0890-4065(02)00048-8

- Tummala-Narra, P., Sathasivam-Rueckert, N., & Sundaram, S. (2013). Voices of older Asian Indian immigrants: Mental health implications. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 44(1), 1–10. doi: 10.1037/a0027809

- Warburton, J., Bartlett, H., & Rao, V. (2009). Ageing and cultural diversity: Policy and practice issues. Australian Social Work, 62(2), 168–185. doi: 10.1080/03124070902748886

- Wilcock, A. A., & Hocking, C. (2015). An occupational perspective of health. Thorofare, NJ: Slack.

- Wright-St Clair, V. A., & Nayar, S. (2017). Older Asian immigrants’ participation as cultural enfranchisement. Journal of Occupational Science, 24(1), 64–75. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2016.1214168