ABSTRACT

This article presents research findings from an urban sociology study of the practice of Palestinian oral transmission in the face of deculturalization. The concept of deculturalization (Spring, 2004) is adopted to enable the analysis of intertwined processes of marginalization and deprivation in their spatiotemporal extension and their impact on the communities concerned. Using the Reflexive Grounded Theory Methodology (RGTM), the research explored how Palestinian refugees in Jordan, Palestine, and Israel conceptualize and practise oral transmission and how their practice mirrors the deculturative condition they experience. Participatory observation and guided interviews were conducted with 13 families, each with three generations, and a number of activists and scientists. Combining the RGTM with elements adopted from Systematic Metaphor Analysis enabled the discovery of inversion as Modus Operandi of oral transmission and as a strategy of dealing with deculturalization. It revealed oral transmission as meta-occupation that facilitates other occupations, operates as a means of knowledge and space production, constitutes belonging, and unifies a scattered community across time and space. Thus, oral transmission has the potential to defy occupational injustice (Stadnyk, Townsend, & Wilcock, 2010) and to undermine and partly undo the impact of deculturalization. This article provides significant insights into the occupation of oral transmission among Palestinians and its function within processes of deculturalization, and potentially amplifies occupational science understandings of these processes in relation to occupation. Categorizing oral transmission as meta-occupation adds to occupational science terminology and may constitute an appropriate category to connect with other disciplines, promoting occupational perspectives.

This article presents parts of my research findings that relate to the practice of Palestinian oral transmission in the face of deculturalization from an occupational perspective.Footnote1 This perspective, however, was only applied subsequently, as it was induced by the findings themselves. Understanding processes of deculturalization as a major challenge to the occupational engagement of individuals and communities makes their impact a fundamental issue for promoting occupational justice. Experiences of deculturalization involve massive loss, disconnection, and fragmentation, causing dysfunction and damage to a target culture. Precipitating crisis, they provoke resistance (Bidney, Citation1946) and induce the implementation of coping strategies, also on the occupational level.

In the Palestinian context, flight, expulsion, and life under military occupationFootnote2 or as refugees in the diaspora, manifest a contrastive context for researching occupation under deculturative circumstances. Given the background of a fundamental denial or violation of basic human rights (United Nations [UN], Citation2016b), it allows the researcher to describe the deculturative condition that was and is created by ongoing deculturalization, and to learn about relevant strategies and resources in responding to, and in coping and dealing with it. In trying to understand the reciprocity of both, the impact of deculturalization on occupation and occupation as an answer to the deculturative condition can be brought into focus. To do so, I highlight two distinctive features of the data that caught my attention early in my research, and which I want to reflect upon within this paper as they can be considered relevant in terms of occupational theory and science. Before presenting these parts of my findings, I provide more information about the research question, its genealogy and theoretical implications, followed by a description of the applied methodology and the research design. The findings themselves are illustrated using data, and finally summarized.

Research Question: A Genealogy

The development of research questions in the humanities is informed by many factors, some of which are intimately connected to the person of the researcher (Breuer, Citation2010; Charmaz, Citation2010). In regard to the employed reflexive grounded theory methodology, laying open the researcher’s background as well as the genealogy of the research question are already part of the methodological procedure and comply with the quality criteria of transparency and intersubjective traceability.

Although my own background as a daughter of a Palestinian family retrospectively constitutes one of these factors, while developing my research question it was not in my focus. Its trajectory seemed rather to be determined by other factors of my biography that influenced my ideas and decisions and led to the final research question. Born and raised in Germany, I studied architecture at a German University and later obtained a postgraduate degree from the Art Academy. Meanwhile, my socio-political commitment in the realm of anti-racism work constituted a parallel field to my main educational and occupational background. It was this field of occupation which gave rise to my attitude, which can best be described as “empathic with the victims of discrimination” (Reisigl & Wodak, Citation2001, p. 35). This attitude developed into a decolonial stance (Masalha, Citation2012; Said, Citation2003; Santos, Citation2014; Simaan, Citation2017) that informed my positionality in regard to this study.

Starting as a voluntary worker, I had taken on professionalized tasks, including state-funded projects, some of which I had developed and conceptualized myself. After many years of engagement, I began questioning the usefulness of such projects, particularly in regard to their benefit for those affected by racism and discrimination. I assumed that there must be strategies and resources these groups resort to in order to handle long-term experiences of discrimination, marginalisation, and deprivation. To understand those experiences and their impacts from a systemic point of view and consider all the relevant aspects, I adopted the concept of deculturalization as the overarching theoretical frame for my study. In search for potential strategies to explore, reading Haley’s (Citation1976) “Roots” and the famous 1001 Nights or Arabian Nights (Mahdī & Ott, Citation2009) led me to the idea that oral tradition (Vansina, Citation1985) or oral history (Abrams, Citation2010) might be possible objects of research. This idea was supported by the work of the Danish historian Erichsen (Citation2008), who collected Oral Histories in Namibia. He had noticed that some tribes had better managed to recover from genocide than others and assumed a correlation between their actual practice of oral transmission and the ability to cope with their experiences of violence and loss.

Finally, the selection of Palestinian oral transmission as my research field resulted from considerations in regard of the conditions of the field as well as my personal resources as researcher. The chosen field had to fit the criteria of an ongoing deculturative process (as will be explicated below), in order to provide the possibility of understanding its impact on the parties involved, as well as a positively connoted and still practised oral transmission (Abdel Jawad, Citation2005, Citation2006; Abrams, Citation2010; Ayalon, Citation2004; Berger Gluck, Citation1994; Sayigh, Citation1979) that can be explored. Additionally, my personal resources, such as the command of Arabic and English as the required languages in the field, were to enable me to access the field and collect rich data.

The concept of deculturalization

Employing the concept of deculturalization, I aimed to achieve an encompassing and comprehensive perspective on experiences of and responses to discrimination, marginalisation, and deprivation. In this regard, the overarching concept of deculturalization proved very beneficial as it allowed for a long-term, process-oriented, and relational understanding.

With his concept, Spring (Citation2004) focussed on processes that are induced by othering and borne by racist ideas of superiority and inferiority. Racism, which Spring defined as “prejudice plus power” (Spring, Citation2004, p. 5), is supposed to legitimize and inform a wide range of practices of deculturalization that affect the targeted communities. Based on racist ideas, according to Spring, settler colonialism makes use of different practices and strategies of deculturalization to reach its aim of cultural and ethnic homogeneity in the target territory (Spring, Citation2004, p. 96).

Thus, deculturalization can be identified as intended deformation of a targeted culture aiming at long-term control and dominion over a target group. In “Deculturalization and the struggle for equality – a brief history of the education of dominated cultures in the United States,” Spring (2004) examined different practices of deculturalization in the context of US settler colonialism. Although not indicated within the concept of deculturalization, similar practices have been described by Shafir (Citation2007) and Veracini (Citation2006) for the case of Zionist settler colonialism.Footnote3

Researching processes of deculturalization through the perspective of a targeted community facilitates the reconstruction of their perception of the deculturative condition, and its impact from their realms of experience and interpretation. In their oral transmission, the transgenerational experiences of and responses to the deculturative condition are documented. Thus, their coping strategies and relevant communal and individual resources, as well as ways of resisting and dealing with deculturalization, become traceable.

Field specific deculturative potential

Researching Palestinian oral transmission in Jordan, Palestine, and Israel involves dealing with the impacts of Zionist settler colonialism (Wolfe, Citation2006) in a region that has undergone a lot of change during the last centuries, in which it has witnessed the rise and fall of empires, wars, and colonial rule. Nevertheless, the Nakba (the Palestinian catastrophe), that culminated in the ethnic cleansing of Palestine in 1947/48 (Abdel Jawad, Citation2007; Khalidi, Citation1988; Pappe, Citation2006) emerges as the common vanishing point of oral transmission in the collected data. In their oral accounts, research participants in Jordan, Palestine, and Israel refer in unison to the Nakba as the major change, attributing its impacts unanimously to Zionist settler-colonialism, which they perceive in a continuity with British colonial rule (El-Qasem, Citation2017; see also Davis, Citation2011; Pappe, Citation2006).

On the concrete level, the Nakba did not only mean the experience of violence and war, but also turned the majority of the Palestinian population into long-term refugees in their home country or different neighbouring countries (Abdel Jawad, Citation2007; Khalidi, Citation1988; Pappe, Citation2006). It resulted in the loss of their lands and properties and the scattering of their communities in diasporas (Al Dabbas, Citation2006; Massad, Citation2001; Pappe, Citation2006; Sayigh, Citation1979; United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East [UNRWA], Citation2015). While research participants in Jordan, Palestine, and Israel shared the fate of being Palestinian refugees, their experiences varied depending on where they lived.

Those refugees who managed to stay in the territory that was later declared the state of Israel suffered and still suffer from military rule and legal discrimination (Adalah Citation2011, Citation2018; Masalha, Citation2007; Pappe, Citation2011; United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Citation2012). As Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) they were given Israeli citizenship but were treated as second class citizens and barred from basic rights (Pappe, Citation2011). They were exposed to military attacks, ghettoization, forced labor, abuse, torture, and execution (Abdel Jawad, Citation2005; Pappe, Citation2006). Cases of rape were documented by the Red Cross and the United Nations (Pappe, Citation2006; see also Kassem, Citation2011).

In the Westbank and East Jerusalem, military occupation since 1967 has brought about a further escalation of the situation. Occupation in the researched field continues until these days, becoming manifest in repeated experiences of war, daily violence, and detention (B´Tselem, Citation2015a, b, c), house demolitions (B´Tselem, Citation2018), hundreds of checkpoints, the construction of the illegal separation wall, and the segregation of land and communities (United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territories [UN OCHAoPt], Citation2014, Citation2016), the installation of an apartheid system (Dugard & Reynolds, Citation2013; Tilley, Citation2009, Citation2012; United Nations Economic and social Commission for Western Asia [UN ESCWA], Citation2017) attended and reinforced by occupational apartheid (Lavin, Citation2011, pp. 27-32; Pollard, Kronenberg, & Sakellariou, Citation2008, p. 56), and the ongoing illegal settlement of Jewish-Israeli settlers in the Occupied Territories (Ophir, Givoni, & Hanafi, Citation2009; UN, Citation2016a).

Meanwhile, the lives of Palestinian refugees in Jordan are more or less characterized by a lack of freedom and self-determination, depending on the time period, the treatment of their host country and society, and the legal status they are granted or denied. In correlation with political change, research participants experienced and still experience different degrees of discrimination and marginalization, sometimes culminating to state violence, political persecution, and exile (for the situation of Palestinians in Jordan see Al Dabbas, Citation2006 and Massad, Citation2001).

Whether in Jordan, under military occupation in the Westbank and East Jerusalem (Frank, Citation1996; Lavin, Citation2005, pp. 40-45, Citation2011, pp. 27-32; UN, Citation2015), or in Israel (Kassem, Citation2011; Pappe, Citation2011; Slyomovics Citation1998), the explicated situations relate directly to questions of occupational justice, well-being, and educational and occupational prospects of Palestinian refugees. Albeit different, experiences of Palestinian refugees in Jordan, Palestine, and Israel cannot be sharply separated according to national borders. An intersectional perspective is required to account for the impacts of deculturalization intertwining in the lives of the research participants on the collective, family, and individual levels. Borders here do not limit the scope of the deculturative process to a demarcated territory; they are rather part of and enhance the experience of loss, disconnection, and fragmentation as it emerged from the data. These “colonial effects” (Massad, Citation2001) and the politics of “inclusive exclusion” (Ophir, Givoni, & Hanafi, Citation2009) in and outside Palestine cause what Bidney (Citation1946) calls “cultural crisis” and keep Palestinians in Jordan, Palestine, and Israel occupied in a multilayered process of “deculturalization” (Spring, Citation2004).

What about culture?

However, framing my research within processes of deculturalization raises the question of the underlying notion of culture. As researchers, using the concept of culture has broad implications, which have to be reflected upon in advance. Particularly when considering processes of deculturalization that root in othering and racism, as Spring (Citation2004) illustrated, it is crucial to avoid producing others through the research practice itself. In her essay “Writing against culture” the critical feminist anthropologist Abu Lughod (Citation1991) rejected an essentialist notion of culture and pointed to its abuse and racist potential:

Culture is the essential tool for making other. … In this regard, the concept of culture operates much like its predecessor – race – even though in its twentieth-century form it has some important political advantages. Unlike race, and unlike even the nineteenth-century sense of culture as a synonym for civilization (contrasted to barbarism), the current concept allows for multiple rather than binary differences. (pp. 143-144)

However, a closer look at language usage poses a major challenge when collecting data in different languages (Kruse, Bethmann, Niermann, & Schmieder, Citation2012), in this concrete case in Arabic and English. The process of data analysis had to be reflected upon carefully in terms of when and how to translate data, particularly when writing up the final report in German as a third language added even more complexity to a language sensitive approach. In this regard, several layers intertwined within the presented study, since oral transmission, as a language-based practice, was reflected upon, analysed, and represented by means of written language.

Thus, the issue of translation had to be solved not only to be able to transfer findings, but rather in order to reach optimum benefit, making it a resource of deeper understanding. By implementing a dialogue between the languages, a “tertium comparationis” (Renn, Citation2005, p. 208) with new dimensions of understanding can emerge. This approach builds on the idea of the relationality of languages and results in a reinforcement of the constructivist character of qualitative research. In consequence, translation within my study took the form of an “information offer in a target culture and its language about an information offer from a resource culture and its language” (Reiss & Vermeer, Citation1984, p. 119; my translation). Keywords are used in their transcription of the Arabic origin while explaining the respective connotations and associations in advance. To reduce possible loss in meaning I analysed the data in the original language and wrote codes and categories in German. The interview excerpts in the final report were only translated after analysis and different meanings of keywords were clustered using slashes to provide an idea of inherent connotations to the reader.

Research Design and Methodology

The fieldwork for this study in Jordan, Palestine, and Israel was completed between February and September 2011. This period coincided with the upheavals of the so-called Arab Spring, which posed diverse challenges on the process of data collection. More efforts were necessary in finding research participants due to increased political tension in the region that resulted in more mistrust and caution than usual. Getting appropriate access to the field required an extensive phase of “nosing around” (Breuer, Citation2010, p. 62) and finding keypersons.

Most of the time, I lived in the Jordan capital Amman and met interviewees in different places in Jordan. In this period, I spent 10 weeks in Palestine/Israel, where I lived in a refugee camp in the Westbank. To collect data, I used guided interviews and participatory observation as well as literature and video material. Thirteen families, each with three generations, and a number of activists and scientists whose work was relevant to the research question, were recruited as participants. The final data corpus included 60 interviews and numerous entries in my research journal.

Methodology

The research was carried out using the Reflexive Grounded Theory Methodology (RGTM) according to Breuer (Citation2010). The selection of a constructivist qualitative research design was informed by interest in field specific conceptualizations and the aim to describe them in a theory (Glaser & Strauss, Citation2010). According to Glaser and Strauss (Citation2010), generating theory does not aim at reproducing or representing “facts”, nor at verifying or judging statements and ideas, but at reconstructing field-specific conceptualizations and phenomena based on collected data (Breuer, Citation2010; Charmaz, Citation2010; Glaser & Strauss, Citation2010). Following through the constructivist idea of knowledge that Glaser and Strauss (Citation2010) drew on in their development of GTM as the “mother methodology”, the RGTM extends the scope of data collection to the researcher herself (Breuer, Citation2010; Charmaz, Citation2010). This extension qualifies for the acknowledgement of the fact that researchers cannot produce but “partial” and “positioned truths” (Abu Lughod, Citation1991, p. 142) bound to the researcher’s subjectivity as well as to the subjectivities of research participants and inherent to any research.

Even if unexpected and perturbing, incidents, perceptions, and resonances resulting from the interplay between the researcher and the field are not factored out; nor are they considered to be annoying or problematic for the research process. Rather, they are recorded, used, and analysed just like any other data, since they are understood to provide valuable opportunities to discover and have better insight into the characteristics of the field and emerging phenomena (Breuer, Citation2010). As for this study, recording and analysing my own experiences in and with the field proved useful in introducing a situation that is unknown to most readers of the final report. That included experiences and observations when crossing checkpoints, witnessing violent military interventions in East Jerusalem and in the refugee camp, or visiting places affected by the illegal wall built by Israel in the Westbank.

Following one of the essentials of GTM, namely theoretical sampling, the subsequent combination of the RGTM with elements of the Systematic Metaphor Analysis according to Schmitt (Citation2017) was induced through the process of data analysis itself. As a methodological approach, the Systematic Metaphor Analysis draws on a relational notion of metaphor as it is developed in cognitive linguistics (Lakoff & Johnson, Citation1980), considering metaphors to be representative of collectively shared patterns of thought and thus proper for exploring underlying collective and individual conceptualizations.

While the intent of GTM to generate theory informs all procedural steps in the research process, the GTM specific concept of theory promotes an inductive procedure that builds upon conceptualizations from the field and its protagonists. In consequence, the main quality criterion is the usefulness of the theory produced. According to Glaser and Strauss (Citation2010), this is achieved through fit, relevance, workability, and modifiability of the theory. These features are considered to render the theory comprehensible, applicable, and modifiable in practice, binding it back to the researched field and opening it to comparable contexts (Glaser & Strauss, Citation2010).

Although an ethical approval in the field of social sciences is usually not required in Germany, ethical considerations are of central significance when conducting research under deculturative conditions. For me, this meant not only giving highest priority to the security of the research participants, but also respecting and protecting their dignity, reflecting my own role in the field, and not allowing research to become voyeurism. This involved efforts to reduce power asymmetries between me, as the researcher, and the research participants (Abrams, Citation2010), sharing with them my experiences and discussing with them my ideas. It meant also renouncing from describing all strategies that I observed, as disclosing them could be used to set up more selective restrictions upon them (von Kardoff, Citation2008). The chosen methodology enabled me to take all these aspects into consideration, as it required continuous self-reflection as well as considering the research participants as experts of their own lives, and thus acknowledging their conceptualizations and theorizing achievements (Breuer, Citation2010).

Findings

The “particular” of the field

Trying to understand the particular (Abu Lughod, Citation1991) of the researched field, there were two distinctive features that caught my attention from a very early stage of my research. Tracing these features not only lead to the discovery of the phenomenon of inversion, which I explain below as the central category of the developed Grounded Theory, but also revealed oral transmission to be what I call a meta-occupation.

The first of these two features was the frequency with which the interviewees referred to the earth using the Arabic term ard, which lent a distinctive earthly character to their accounts. This impression can be attributed to the numerous narrations dealing with the earth as soil or ground, talking about its colour, smell or other features, or about occupations in the realm of agriculture or everyday occupations like fetching water, collecting wood, travelling, trading, going to the market or to school. These accounts provide listeners with detailed descriptions of the (lost) home village or town, its infrastructure and topography. What all these accounts have in common is that they put the place at the centre of interest.

The second distinctive feature that caught my attention was the dominance of seemingly banal accounts dealing with commonplace occupations in past everyday life, such as working the land, herding animals, building, baking and cooking, gathering, quarrelling, celebrating, playing, story-telling, etc. Yet, their meaning had to be determined, as the detailed descriptions of some of these occupations did not seem to be connected to the contemporary lives of the listeners due to the accelerated urban transition research participants were exposed to. As a result of colonisation and displacement, this transition took on the shape of a rupture, as it was characterized by the forced and abrupt loss of their habitual environments.

However, in the course of data analysis these two distinctive features turned out to represent what can be understood as the normative order of the particular in the researched field, as it is frequently referred to by the interviewees. Haleema, a third-generation refugee from Palestine, explains:

This is how we are raised from a very young age. Two things are important in your life after your soul, the ard and the `ard, if the ard is lost or if the `ard is lost, you are of no value in this world anymore.

Interviewees often said that the decision to flee their ard(earth) was due to their `ard being threatened. In this context, they usually refer to killings and cases of rape that were committed by Zionist militia as well as the fear of more violations, a fear that was actively spread by those militias (Pappe, Citation2006). In this situation, they considered it their responsibility to save their `ard, and the `ard of women and children in particular. If it was not for that, they would not have left, they said in unison. Correspondingly, in scientific literature in the Palestinian context, and most notably within feminist approaches, `ard (also `ird) is referred to as (female specific) honour (Abu Lughod & Sádi, Citation2007; Humphries & Khalili, Citation2007; Kassem, Citation2011; Sayigh, Citation2007; Slyomovics Citation1998, Citation2007).

However, this popular meaning seems to be only implicitly contained in the literal meaning of `ard: Searching in encyclopaedias and dictionaries reveals different realms of meaning (Ibn Manẓūr, Citation2003; Wehr, Citation1976, pp. 542-544) that can be grouped together in three categories. While the meanings of (1) amplitude, width, property and gift refer to size, amount, availability, and giving, the meanings of (2) ancestry, bodies entrusted in someone’s care and what can be praised or blamed in a person or his / her ancestry seem to be tied to the way bodies are organised, such as lineage, entrustment, the body and its vulnerability. The third realm of meaning includes (3) exhibition, presentation and performance and operates the fields of visibility (showing) and doing. Taking all realms of meaning into account, the use of the term `ard indicates that honour is understood to be vulnerable through the physical body and therefore on the performative and occupational level. At the same time, the particular is depicted through everyday life occupations as a bodily performance of life itself that is tied to a certain place.

This place-tied performance includes various occupations that constitute what I term ‘doing life’Footnote4 while the ard(earth) can be reconstructed as the connecting element that mediates between past, present, and future members of the community and their occupational engagements. Pivotal to the communities’ self-conceptualization, and representative of the normative order of the particular, the intertwined concepts of ard(earth) and `ard(performance) reflect the relationship to the other-than-human elements of the community and its importance (Simaan, Citation2017) as well as the reciprocity and indivisibility of this relationship (Hammell, Citation2011). According to the research participants, the practice of oral transmission plays a central role in establishing and maintaining this relationship.

Oral transmission as constitutive occupation

Asked about their practice of oral transmission, research participants referred to folk talesFootnote5 and religious tales as well as tales that can be categorized as “oral tradition” (Vansina, Citation1985) or “oral history” (Abrams, Citation2010). They considered it to be one of the various occupations of everyday life and described it to be a “natural” and “beautiful” occupation that they have been familiar with since their childhood (El-Qasem, Citation2017). ‘Ali, a second generation refugee in Jordan, explained:

That’s the issue with oral transmission, it never ends. As long as there are following generations, the transmission among us will continue, because this is the human nature, that we always talk about our history.

‘Ali names gatherings, in which members of different generations happen to be there, as occasions for transmitting and receiving oral accounts. Practising oral transmission is not only considered self-evident and characteristic for their own community, but also attributed to the course of time and thus considered inescapable. Furthermore, it is conceptualized as a highly sophisticated, performative, and aesthetic occupation, which can take on ritualized forms. Altogether, the practice of oral transmission is described as constitutive occupation by which their own community is (re-)produced and sustained. According to the data, this continuous (re-)production of the community gains in importance against the background of deculturalization: While the experience of deculturalization materializes in loss, destruction, and disconnection (El-Qasem, Citation2017), oral transmission is conceptualized as a means of restoration, reconnection, maintenance, and growth.

A closer look at how this occupation is performed reveals it as complex and multi-layered practice with which an abundant pool of memories is generated. These memories are received and collected from a very young age. Asked whether there are particular stories they consider to be significant in their lives, Nida and Zainab, third-generation refugees from Jordan, answered:

Nida: You cannot say that there is something particular. As far as I am concerned, my grandfather was, was like a well, you always drink from it, you go on taking from it.

Zaynab: – it never runs out.

Everyone tells from what he has to tell / scoops with his scoop in the ongoing / flowing conversation.

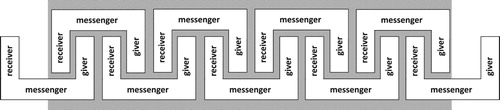

As a constitutive occupation, oral transmission is therefore considered a right, duty, and responsibility of all members of the community. In Arabic, research participants often referred to it as amanah, which means entrusted property. Muhammad, a third-generation refugee from Jordan, described the impact of oral transmission as follows:

And besides, it’s the nature of the stories and their style, as if it gives you an amanah (entrusted property), … he tells it and you feel it, while he is telling it, as if it is living, as if it emerges, this means, as if it has a soul, and as if it is wandering from one to the other. … Then you feel the responsibility, just when he tells you a story, that’s it, you have the responsibility. You have to deliver it to someone, you have to.

It means, for example, we were, our grandparents were, then our parents and then, we are now, and then tomorrow, you want to become, on the basis that it’s a chain and that its links remain connected to each other … you feel yourself in the role, that you are the chain link that connects the past with the future, by having transmitted what has passed by, which is gone, about which they of course do not know anything, you have delivered it, in some way.

While the mode of transmission is represented by the metaphor of the chain, research participants referred to the object of transmission using expressions from the metaphorical concept of seeing and visualizing. Seeing and visualizing become relevant in the deculturative context of the field: In the course of forced migration the loss of the ard(earth) turns it invisible, whereas oral accounts make the ard(earth) visible again. According to the data, the gift that is given within the transmission takes on the form of an image. Listeners are made to see what is represented in the accounts they receive. Asked what she wants to tell her children about Palestine in the future, 17-year-old Iman says: “I will put, draw upon their imagination the same image that is drawn upon my imagination.” Her answer indicates that the transmitted images have to be suitable for repeated transmission in order to reconnect to what was lost in a protracted deculturative condition. According to the research participants, the narrated situation is described in great detail for this purpose. Finally, the images created constitute the pool of memories from which all community members can take. The richness of this pool results in having appropriate memories available for any situation in life, as Muhammad explained:

There is no mawqif that occurs in life, for which I do not find at least one story that was told, for which I do not find at least one available memory.

Reorganisation through inversion

The reconstructed conceptualization of oral transmission as a gift given in the form of an image that is rooted in a standing position (mawqif) makes more comprehensible the impact of the Nakba: Flight, displacement, and military occupation brought about a fundamental change to the normative order of ard(earth) and `ard(performance). After their segregation from their ard(earth), it was no longer available and their `ard(performance) on it had been violently disrupted. Being deprived of the ard(earth) meant that their mawqif as standing position was literally lost.

This extensive distortion of their transactional system required its reorganisation. Being displaced meant, to the field members, leaving and taking the ard(earth) with them, incorporating it through the means of oral transmission. This incorporation is enabled through a modification of the normative order of the particular. Its reorganisation is expressed by the in Vivo code “Others live in their homeland, our homeland lives inside us”, which was used by the research participants and can be found throughout the data. It describes what I call the ‘inversion’ of the normative order of ard(earth) and `ard(performance).

The term inversion can be found in various disciplines, such as linguistics, mathematics, physics, geology, and meteorology. It always refers to a potential permutability, which allows preservation of the whole, even if parts of it alter their position according to a basic normative order. This basic order can be restored by repeated inversion. The principle of inversion is well known from the phenomenon of tilted images where there are two images in one, depending on the way you look at it.

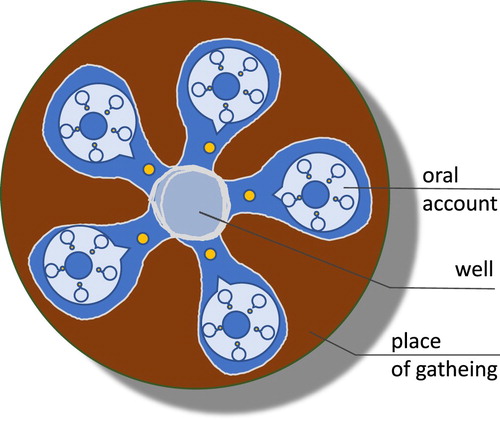

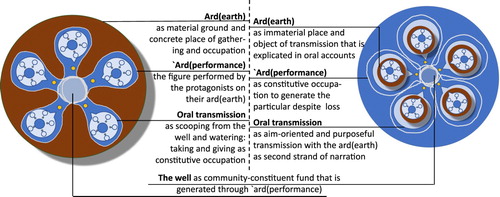

In regard to the researched practice of oral transmission, it is by the inversion of the normative order of the particular that the reconstruction and restoration of the lost homeland through oral accounts is implemented. In their narrations, Palestinians still populate their places of origin by projecting a detailed fabric and snapshots of past daily life onto a landscape that most of them cannot reach physically. The place itself emerges within the narrated occupations as a lived and experienced place that can be visualized mentally. On the micro-level, this inversion can be reconstructed as depicted in .

In the normative order, the protagonists with their performance of everyday life form the figure on the ard(earth) as their ground. However, its loss triggers a reorganisation of their particular. While knowledge of and experience with the ard(earth) used to be implicitly shared among the members of the community within the normative order, the ard(earth) as place emergent through occupation (Frank, Citation2011; Dickie, Cutchin, & Humphry, Citation2006) and commonly shared space is no longer available after flight and displacement. In consequence, the ard(earth) as the formerly implicit strand of transmission has to be made explicit within narration. This is achieved through detailed descriptions, transforming the ard(earth), once the material ground and place of gathering, into an immaterial place that can be passed on. Oral transmission and with it the performance of everyday occupations are no longer the figure, but the ground on which the ard(earth) appears as figure. The community members become the carriers of the ard(earth) that formerly served as the raw material of space production for their communities and as the carrier of their performance.

However, everyday commonplace occupations do not exist by themselves, and neither does the corresponding knowledge (Frank, Citation2011). They are always framed within a transactional system through which both individual and communal meaning are achieved. To be able to set up their own frame after its damage, the protagonists in the field have made explicit the formerly implicit knowledge and become its performative representatives. In their accounts, past everyday occupations and their places are intertwined with current everyday issues and occupations. These accounts provide listeners with a detailed and contextualized portrayal of past protagonists as occupational subjects, and reproduce the frame within which their occupations were located and valid.

Although such efforts “cannot reproduce or restore a prior state” (Frank, Citation2011, p. 15), they counter the deculturative experience. According to the conceptualizations of the research participants, these narrated occupations are expressions and representations of their particularities, their identities and their very being. While experiences of displacement and military occupation are perceived as denial of their very being, they secure individual and communal resources with the help of oral transmission. Oral accounts provide the members of the community with what was rendered out of reach or made invisible through deprivation, helping them to perpetuate their collective activity system (Engeström, et al., Citation1999, p. 34) despite loss. In doing so, they produce meaning and render value to themselves as occupational subjects. Amra, a third-generation refugee from Jordan, described it as follows:

As you know, someone who has no past has no present, I listen to these stories, and it makes me really proud of the past, that is repeated and that I have been hearing for years, and I come back and hear it again, and in fact, whenever I hear it, it makes me proud of this past, and then I know, that I have a future, that I have a present that I have to be proud of and feel its value, and, too, that I have to build a future for my grandchildren, so that they can hear of it and can be proud of it. I feel the responsibility.

However, while Amra described receiving oral accounts about the past as an assignment to “build a future”, the ability to envision a future is impaired within the deculturative condition (El-Qasem, Citation2017, p. 298). Winkler (Citation2006) considered “a collective memory” (p. 277; my translation) as well as its “entitlement to durability” (p. 277; my translation) as identifying features of the particular, lending it validity and credibility and making it eligible for transmission to succeeding generations. Thus, being thrown off time (and place) not only induces a rupture in regard to the past, but also in regard to the future. Loss in the researched field is not limited to the ard(earth), it rather includes an abrupt and enduring interruption on the performative and occupational level as well as on the time and community level, turning the hitherto existing transactional system invalid.

In response, protagonists establish the corresponding frame and render continuity and coherence to their particular with their practice of oral transmission. Meanwhile, the occupation of doing life can be defined as the ongoing production of standing positions within this frame that are worth being narrated. Thus, the practice of oral transmission functions as a means of reclaiming identity and belonging, while defying occupational injustice and deprivation (Stadnyk, Townsend, & Wilcock, Citation2010).

However, occupational deprivation does not only affect occupation itself but impairs the environment of the targeted communities. It is precisely because refugees were deprived of their home and lands as their occupational context, that they suffer occupational deprivation. This deprivation is not limited to the individual loss nor to an event or contained period of time. It rather constitutes a transgenerational loss as experiential, traditional, and occupational knowledge is decontextualized and thus difficult to convey and preserve. According to Frank’s (Citation2011) transactional approach, “ruptures in the reproduction and transmission of a people’s experience or culture provoke responses that are expressed through occupations – that is doing things to adapt and achieve a new equilibrium” (p. 8). Thus, protagonists reconstruct the lost occupational context in a symbolic manner in order to defy occupational deprivation. One occupation can symbolize another, while at the same time creating the surrounding universe, as Zaynab and Hasan, third-generation refugees from Jordan, explained:

Zaynab: We heard about Palestine from our grandfather, he always told us stories about Palestine … he said: “You have not lived in Palestine, you don’t know Palestine, we used to go down to the ard(earth), to”, he has given it to you. He has embodied Palestine, as if you could see it directly.

Hasan: He let it [Palestine] grow inside them.

Zaynab: Even if it was a little grape, a little tendrill, that he planted at his home, on the basis that ‘it reminded me of Palestine and the way we used to plant and what we used to do in Palestine … and take care of the tree.’ Imagine, on the level of a tree, he made you feel that this tree is a prolongation / perpetuation, it is the soul of a life still to come. He tied it down to the ard(earth) and tied it down to Palestine.

At times, the impact of doing life can be enhanced by ritualizations. These ritualizations serve as a tool to “establish a relationship to a different world” (Wulf, Citation2004, p. 11; my translation) by which an “additional (experiential) space is created” (El-Qasem, Citation2017, p. 343; my translation). The effectiveness of ritualizations can even result in the compensation of loss on the level of family relatives, as Rafiqa, a second-generation refugee from Jordan, described from her childhood experience:

She [our mother] never let us feel that my father was absent, even on the level, when my siblings were young and wanted to have their pocket money. They said: ‘Mummy, give us pocket money’, then she [her mother] says: ‘My mother, I have no money, your father has not sent any.’ Then he [her brother] says: ‘Mummy, what can we do, we need the money.’ Then she says: ‘There is the image of your father, go, and tell your father that you need money.’ She stands behind us, when, my brother and I say to him: ‘We need money, our mother has not given us any today.’ She takes the money and throws it at the image. So to make us think, that it is from our father. And it came down. ‘Mummy, look, Daddy has answered us and given us money’, imagine. So she never let us feel that my father was absent.

Given the previously described impacts of the practice of oral transmission in the face of deculturalization, it is not surprising that research participants displayed high reflexivity and strong awareness of its functions. This goes along with a distinctive occupational consciousness (Ramugondo, Citation2015; Simaan, Citation2017). Research participants, in unison, considered loss, disconnection, and fragmentation, as well as the Israeli “politics of denial” (Masalha, Citation2003) and silencing to be a threat to their culture and identity, whereas they all agreed that the practice of oral transmission is a form of resistance in itself while facilitating other forms of resistance. Securing access to their particular in spite of massive loss has the potential to undermine and partly undo its effects. The employed metaphors of water, of the chain, of planting, and of seeing and visualizing not only demonstrate the “mutual association of individual and context” (Simaan, Citation2017, p. 11) but also include the association of the collective as a third parameter (Ramugondo & Kronenberg, Citation2015) and imply a future or, as Zaynab put it, “a life still to come”.

While Peteet (2005) considered “the ability [of Palestinian refugees] to craft meaningful places” (p. 183) as pivotal in countering deculturalization, I would take a more holistic stance. According to the presented study, I would rather argue that the strategy of inversion as it is emergent in the practice of oral transmission facilitates their ability to (re-)establish relationships and reconnect after loss and disconnection, while extending the “temporal and spatial dimensions” (Dickie et al., Citation2006, p. 88) of their transactional system beyond the realities of the deculturaltive condition they experience. This includes “the ability to craft meaningful places” (Peteet, Citation2005, p. 183) even if these places were to be within themselves, making their homeland live “inside” them, as well as the ability to envision a meaningful and self-determined future against all odds.

Summary

Flight, expulsion and life under military occupation, understood as symptoms of a process of deculturalization, pose multidimensional challenges on the community concerned. Massive loss and disconnection from pivotal reference points in the past, present, and future turn the frame within which occupation is located invalid. Thus, life and occupation as doing life in the researched field suffer from extraordinary stress and a lack of self-determination, security, and predictability.

Meanwhile, oral transmission as constitutive occupation endows the protagonists with the ability to compensate for some of the impacts of the deculturative condition they live in. It operates as a means of knowledge and space production. Moreover, it is employed as a tool to establish the frame of the particular and re-implement it. Furthermore, it is a means to represent the protagonists as occupational subjects, using their example to teach doing life as an activity situated on the ground and expressed through occupational engagement. Oral transmission as an educational tool helps raise future generations by providing them with lost objects of acquisition. An entanglement of present and past everyday occupations through oral transmission allocates occupational knowledge to the members of the community and ensures the continuity, coherence, and validity of their experience. It enables protagonists to produce meaning and re-enact their community including the other-than-human elements, and, in doing so, render value to their particular on the individual and communal level. Thus, oral transmission can be considered a meta-occupation that facilitates a wide range of occupations under deculturative circumstances by providing knowledge, consciousness, context, continuity, and meaning, thus framing present day occupations beyond the deculturative condition. In a transactional reading of a situation that has evolved in the course of deculturalization and involved loss and disconnection, this framing allows for a decolonial stance that is mirrored in everyday life occupations, potentially turning them into acts of resistance.

Conclusion

The presented Reflexive Grounded Theory provides a comprehensive reconstruction of the practice of Palestinian oral transmission in the face of deculturalization. This was possible due to a paradigmatic shift: While prior work on Palestine and Palestinians has understood `ard as (female) honour, re-reading it “against culture” (Abu Lughod, Citation1991) resulted in a performance-based understanding. `Ard as doing life, manifest in everyday occupations, revealed oral transmission as a meta-occupation that facilitates all other occupations by providing necessary performative and occupational knowledge and conditions that enable what Wilcock (Citation2006) described as doing, being, becoming, and belonging.

Furthermore, the identification of the concepts of ard(earth) and `ard(performance) as field specific particular, and the discovery of the strategy of inversion, documented the importance of oral transmission as a tool to reframe, re-establish, regenerate, and maintain the field specific particular in spite of an ongoing process of deculturalization. As such, it constitutes a way of resisting and fighting for occupational justice in a harsh settler colonial reality. Moreover, the conceptualizations of the particular as well as those of the practice of oral transmission were identical, no matter whether the research participants lived in Jordan, Palestine, or Israel, and no matter which generation they belonged to or which religious, educational, and economic backgrounds they had. This overwhelming agreement indicates that oral transmission may not only be considered a meta-occupation, in the sense that it facilitates other occupations. It can rather be understood as a means to enable belonging across time and space and therefore to constitute a unifying force, defying the scattering of the own community and its disconnection from its homeland, expressed in what Simaan (Citation2017) termed “daily forms of resistance”.

In addition, the spelling out of the deculturative condition from the perspective of those concerned by it as mainly characterized by experiences of loss and disconnection can contribute to a better understanding of other contexts, such as experiences of violence, trauma, disability, illness, or ageing. Meanwhile, the strategy of inversion as well as recounting everyday commonplace occupations as a means of regenerating and maintaining the particular could benefit other fields dealing with or researching human occupation, including social and political sciences, anthropology, and sociology.

While this study focused on and thus is limited to Palestinian oral transmission in Jordan, Palestine, and Israel, further research exploring the explicated strategies and modi of human occupation will be helpful in highlighting self-led responses to deculturalization in its manifold manifestations. To test and expand the scope of the developed theory, more research could be done on Palestinian oral transmission in the diaspora as well as on other refugee or travelling communities and their oral practices, particularly those who experienced repeated displacement or expulsion.

Furthermore, the results of this study encourage more research of non-Western daily occupations done in non-Western settings, in order to defy occupational and cognitive injustice (Simaan, Citation2017) and theoretical imperialism (Hammell, Citation2011) by acknowledging that beyond Western hegemony there is much we can learn from other ways of knowing, doing, and being.

Notes

1. This article is based on a presentation titled “Occupation under occupation – Everyday life and its significance in processes of deculturalization” delivered at the Occupational Science Europe Conference 2017 in Hildesheim, Germany. I used “Occupation under occupation” as a wordplay which refers to the different meanings of the term occupation and their intertwining in the researched field. These different levels of meaning range from occupation, as it is dealt with in occupational science, and being occupied with something or in a situation, to military occupation. However, these meanings intertwine in the researched field. For example, military occupation in the Westbank has an impact on occupational scopes, not only for those living there, but also for their relatives in the diaspora. After I learned that Lavin (Citation2005) had published a book chapter titled “Occupation under Occupation: Days of Conflict and Curfew in Bethlehem”, to which I refer in this article, I decided to modify the title.

2. To enable a clear differentiation of occupation as human being and doing (in the sense it is used in occupational science) from occupation in the military or territorial sense, the term “military occupation” is employed to denote the latter meaning.

3. With regard to the comparability and resemblance of settler colonial endeavours, including Zionist settler colonialism, Veracini (Citation2008) suggested to “consider a Western settler colonial consciousness as a discursive and ideological practice utilizing a ‘settler archive’ that was constituted through numerous passages of political, religious, and colonial histories during the last five centuries” (p. 148). He developed the term ‘settler archive’ to describe “a repertoire of images, notions, concepts, narratives, stereotypes and thoughts” (Veracini, Citation2008, p. 149) and elaborated on the intersection of colonial, settler colonial, racist and genocidal practices in and outside Europe. Veracini (Citation2008) pointed out that “this archive is constantly tested, updated, added to, in progress … readily available to be mobilized in different contexts” (p. 148).

4. As far as I know, the term “doing life” has not been used in occupational science. In this article, I use doing life for the various occupations that protagonists refer to in their oral transmissions. According to the data, these references encompass all kinds of occupations through which the narrated protagonists “transact with the world” (Dickie et al., Citation2006, p. 90) and that are – in their repetition – modified due to changing situations. This interpretation correlates with the understandings of research participants and mirrors in the concepts of ard(earth) and `ard(performance) as they are explicated in this paper. Thus, oral accounts can be understood as representations of possible modes and systems of transaction that are narrated and passed on as a repertoire. However, descriptions of doing life gain particular significance against the background of the dominant Israeli narrative, in which the existence of Palestinian life as such or its equal value is denied: By portraying Palestinians as either non-existent or underdeveloped and nomadic, Palestinian life is rendered removable (Wolfe, Citation2008, p. 113), while at the same time unmaking its removal (El-Qasem, Citation2017, p. 82).

5. A collection of traditional Palestinian folk tales titled Speak, Bird, Speak Again: Palestinian Arab Folktales was published by Muhawi and Kanaana (Citation1989). It can be accessed online: https://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/view?docId=ft4s2005r4&brand=ucpress

6. The notion of community that emerges from the data can be understood as a construct referring to social fabrics that are considered relevant and applies to different levels of relationship. It can refer to the extended family, the former neighbourhood, the former village or town, as well as to the Palestinian people as an ethnic group. The different concepts of community that can be reconstructed from the data prove to be convergent with the inclusive additivity (Ong, Citation1987) that is characteristic of “orally based thought” (Ong, Citation1987, p. 37). Community consists of communities, just as history consists of (hi)stories and Palestine as an entirety is made up of all places it comprises (El-Qasem, Citation2017, p. 247). Furthermore, community encompasses the other-than-human elements of the community, as explicated above. This data-based understanding correlates with the transactional approach in occupational science, as it is adopted by Dickie and colleagues (2006) and Frank (Citation2011), building on the philosophy of John Dewey. In fact, the inclusive additivity that mirrors in the researched practice of oral transmission can be connected to the idea of “organism[s]-in-environment-as-a-whole” (Dewey & Bentley, in Dickie et al., Citation2006, p. 88), in which all elements, human and other-than-human are understood as interdependent, co-emergent and co-constitutive.

References

- Abdel Jawad, S. (2005). Limādhā lā nastaṭī` kitābat tārīkhinā al mùāṣir min dūn istikhdām al tārīkh al shafawī? ḥarb 1948 ka ḥala dirasiyyah [Why we cannot write our modern history without oral history: The 1948 war as case study]. Maǧallat al-dirāsāt al-falasṭīniyyah [Journal of Palestine Studies], 16/64, (Autumn). Retrieved from http://www.palestine-studies.org/sites/default/files/mdf-articles/6606.pdf

- Abdel Jawad, S. (2006). Durrat al ghawwāṣ fi awhām al khawāṣṣ - al maṣādir al shafawiyyah wa kitābat al tārikh al ijtimā`ī li falastīn bayn muqāribatayn [The pearl of the diver in the fantasies about particularities: Oral sources and the historiography of the society in Palestine between two approaches]. Maǧallat al-dirāsāt al-falasṭīniyyah [Journal of Palestine Studies], 17/67, (Summer). Retrieved from http://www.palestine-studies.org/sites/default/files/mdf-articles/7130.pdf

- Abdel Jawad, S. (2007). Zionist massacres: The creation of the Palestinian refugee problem in the 1948 war. In E. Benvenisti, C. Gans & S. Hanafi (Eds.), Israel and the Palestinian refugees (pp. 59–127). Berlin, Germany: Springer.

- Abrams, L. (2010). Oral history theory. London, UK: Routledge.

- Abu Lughod, L. (1991). Writing against culture. In R. G. Fox (Ed.), Recapturing anthropology: Working in the present (pp. 137–154, 161-162). Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press.

- Abu Lughod, L., & Sàdi, A. H. (2007). Nakba. Palestine, 1948, and the claims of memory. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Adalah. (2011). The inequality report: The Palestinian Arab minority in Israel. Haifa: Adalah. Retrieved from https://www.adalah.org/uploads/oldfiles/upfiles/2011/Adalah_The_Inequality_Report_March_2011.pdf

- Adalah. (2018). The discriminatory laws database. Retrieved from https://www.adalah.org/en/law/index

- Al Dabbas, K. (2006). Palestinians in Jordan: Integration, social disaffection and political conflicts: An empirical study. Berlin, Germany: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Berlin.

- Ayalon, A. (2004). Reading Palestine: Printing and literacy, 1900-1948. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

- Berger Gluck, S. (1994). An American feminist in Palestine: The Intifada years. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

- Bidney, D. (1946). The concept of cultural crisis. American Anthropologist, 48(4), 534–552. doi: 10.1525/aa.1946.48.4.02a00030

- Breuer, F. (2010). Reflexive grounded theory: Eine Einführung in die Forschungspraxis [Reflexive grounded theory: An introduction into research practice]. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer VS.

- B´Tselem. (2015a). Footage from Hebron: Israeli military enables 5-day settler attack, 2015. Retrieved from http://www.btselem.org/video/20151027_5_days_of_settler_attacks_in_hebron

- B´Tselem. (2015b). Statistics on Palestinians in the custody of the Israeli security forces. Retrieved from http://www.btselem.org/statistics/detainees_and_prisoners

- B´Tselem. (2015c). Statistics on Palestinian minors in the custody of the Israeli security forces. Retrieved from http://www.btselem.org/statistics/minors_in_custody

- B´Tselem. (2018). Statistics on punitive house demolitions. Retrieved from https://www.btselem.org/punitive_demolitions/statistics

- Charmaz, K. (2010). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

- Davis, R. (2011). Palestinian village histories: Geographies of the displaced. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Dickie, V., Cutchin, M. P., & Humphry, R. (2006). Occupation as transactional experience: A critique of individualism in occupational science. Journal of Occupational Science, 13(1), 83–93. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2006.9686573

- Dugard, J., & Reynolds, J. (2013). Apartheid, international law, and the Occupied Palestinian Territory. European Journal of International Law, 24(3), 867–913. doi: 10.1093/ejil/cht045

- El-Qasem, K. (2017). Palästina erzählen: Inversion als Strategie zur Bewahrung des Eigenen in Dekulturalisierungsprozessen [Narrating Palestine: Inversion as a strategy to preserve the particular in processes of deculturalization]. Bielefeld, Germany: Transcript.

- Engeström, Y., Miettinen, R., & Punamäki, R.-L. (Eds.). (1999). Perspectives on activity theory. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Erichsen, C. (2008). What the elders used to say. Windhoek, Namibia: Namibia Institute for Democracy.

- Frank, G. (1996). Craft production and resistance to domination in the late 20th century. Journal of Occupational Science, 3(2), 56–64. doi: 10.1080/14427591.1996.9686408

- Frank, G. (2011). The transactional relationship between occupation and place: Indigenous cultures in the American Southwest. Journal of Occupational Science, 18(1), 3–20. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2011.562874

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (2010). Grounded theory: Strategien qualitativer Forschung [Grounded theory: Strategies in qualitative research]. Bern, Switzerland: Huber.

- Haley, A. (1976). Roots: The saga of an American family. New York: Doubleday & Co.

- Hammell, K. W. (2011). Resisting theoretical imperialism in the disciplines of occupational science and occupational therapy. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(1), 27–33. doi: 10.4276/030802211X12947686093602

- Humphries, I., & Khalili, L. (2007). Gender of Nakba memory. In L. Abu Lughod & A. H. Sàdi (Eds.), Nakba: Palestine, 1948, and the claims of memory (pp. 207–228). New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Ibn Manẓūr, M. (2003). Lisān al-ʿArab. Encyclopedia of the Arabic language. Retrieved from http://www.baheth.info/

- Kassem, F. (2011). Palestinian women: Narrative history and gendered memory. London, UK: ZED Books.

- Khalidi, W. (1988). Plan Dalet: Master plan for the conquest of Palestine. Journal of Palestine Studies, 18(1), 4–33. doi: 10.2307/2537591

- Kiepek, N., Beagan, B., Laliberte Rudman, D., & Phelan, S. (2018). Silences around occupations framed as unhealthy, illegal, and deviant. Journal of Occupational Science. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2018.1499123

- Krämer, S. (2008). Medium, Bote, Übertragung: Kleine Metaphysik der Medialität [Medium, messenger, transmission: Little metaphysics of mediality]. Frankfurt, Germany: Suhrkamp.

- Kruse, J., Bethmann, S., Niermann, D., & Schmieder, C. (Eds.). (2012). Qualitative Interviewforschung in und mit fremden Sprachen. Eine Einführung in Theorie und Praxis [Qualitative interview research in and with foreign languages: An introduction to theory and practice]. Weinheim, Germany: Beltz Juventa.

- Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Lavin, B. (2005). Occupation under occupation: Days of conflict and curfew in Bethlehem. In F. Kronenberg, S. Simó Algado & N. Pollard (Eds.), Occupational therapy without borders: Learning from the spirit of survivors. London, UK: Elsevier.

- Lavin, B. (2011). Meeting the needs for occupational therapy in Gaza. In F. Kronenberg, N. Pollard, & D. Sakellariou (Eds.), Occupational therapies without borders: Towards an ecology of occupation-based practice (Vol. 2). London, UK: Elsevier.

- Mahdī, M., & Ott, C. (2009). Tausendundeine Nacht [1001 Nights]. München, Germany: Beck.

- Masalha, N. (2003). The politics of denial: Israel and the Palestinian refugee problem. London, UK: Pluto Press.

- Masalha, N. (2007). Present absentees and indigenous resistance. In I. Pappe (Ed.), The Israel/Palestine question: A reader (pp. 255–284). London, UK: Routledge.

- Masalha, N. (2012). The Palestine Nakba: Decolonising history, narrating the subaltern, reclaiming memory. London, UK: Zed Books.

- Massad, J. A. (2001). Colonial effects: The making of national identity in Jordan. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Muhawi, I., & Kanaana, S. (1989). Speak, bird, speak again: Palestinian Arab folktales. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Ong, W. (1987). Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the world (Repr. ed.). London, UK: Methuen.

- Ophir, A., Givoni, M., & Hanafi, S. (Eds.). (2009). The power of inclusive exclusion: Anatomy of Israeli rule in the occupied Palestinian Territories. New York, NY: Zone books.

- Pappe, I. (2006). The ethnic cleansing of Palestine. London, UK: Oneworld Publications.

- Pappe, I. (2011). The forgotten Palestinians: A history of the Palestinians in Israel. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Peteet, J. (2005). Landscape of hope and despair: Palestinian refugee camps. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Pollard, N., Kronenberg, F., & Sakellariou, D. (2008). Occupational apartheid. In N. Pollard, D. Sakellariou & F. Kronenberg (Eds.), A political practice of occupational therapy (pp. 55–67). London, UK: Elsevier.

- Ramugondo, E. L. (2015). Occupational consciousness. Journal of Occupational Science, 22(4), 488–501. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2015.1042516

- Ramugondo, E. L., & Kronenberg, F. (2015). Explaining collective occupations from a human relations perspective: Bridging the individual-collective dichotomy. Journal of Occupational Science, 22(1), 3–16. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2013.781920

- Reisigl, M., & Wodak, R. (2001). Discourse and discrimination: Rhetorics of racism and antisemitism. London, UK: Routledge.

- Reiss, K., & Vermeer, H. J. (1984). Grundlegung einer allgemeinen Translationstheorie [Basics of a general translation theory]. Tübingen, Germany: Niemeyer.

- Renn, J. (2005). Die gemeinsame menschliche Handlungsweise: Das doppelte Übersetzungsproblem des sozialwissenschaftlichen Kulturvergleichs [The common human way of acting: The double translation problem in comparing cultures in social sciences]. In I. Srubar (Ed.), Kulturen vergleichen: Sozial- und kulturwissenschaftliche Grundlagen und Kontroversen [Comparing cultures: Basics and controversies in social and cultural sciences] (pp. 195–227). Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer VS.

- Said, E. W. (2003). Orientalism. London, UK: Penguin.

- Santos, B. S. (2014). Epistemologies of the South: Justice against epistemicide. Oxon, UK: Routledge.

- Sayigh, R. (1979). Palestinians: From peasants to revolutionaries. London, UK: Zed Press.

- Sayigh, R. (2007). Women’s Nakba stories: Between being and knowing. In L. Abu Lughod & A. H. Sàdi (Eds.), Nakba. Palestine, 1948, and the claims of memory (pp. 135–160). New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Schmitt, R. (2017). Systematische Metaphernanalyse als Methode der qualitativen Sozialforschung [Systematic metaphor analysis as method in qualitative research]. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer VS.

- Shafir, G. (2007). Zionism and colonialism: A comparative approach. In I. Pappe (Ed.), The Israel/Palestine question: A reader (pp. 78–93). London, UK: Routledge.

- Simaan, J. (2017). Olive growing in Palestine: A decolonial ethnographic study of collective daily-forms-of-resistance. Journal of Occupational Science, 24(4), 510–523. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2017.1378119

- Slyomovics, S. (1998). The object of memory: Arab and Jew narrate the Palestinian village. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Slyomovics, S. (2007). The rape of Qula, a destroyed Palestinian village. In L. Abu Lughod & A. H. Sàdi (Eds.), Nakba. Palestine, 1948, and the claims of memory (pp. 207–228). New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Spring, J. (2004). Deculturization and the struggle for equality. A brief history of the education of dominated cultures in the United States. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Stadnyk, R., Townsend, E., & Wilcock, A. (2010). Occupational justice. In C. H. Christiansen & E. A. Townsend (Eds.), Introduction to occupation: The art and science of living (2nd ed., pp 329–358). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

- Tilley, V. (Ed.). (2009). Occupation, colonialism, apartheid? A re-assessment of Israel’s practices in the occupied Palestinian territories under international law. Retrieved from http://www.hsrc.ac.za/en/research-data/ktree-doc/8420

- Tilley, V. (Ed.). (2012). Beyond occupation: Apartheid, colonialism and international law in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. London, UK: Pluto Press.

- United Nations. (2015). Economic and social repercussions of the Israeli occupation on the living conditions of the Palestinian people in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, and the Arab population in the occupied Syrian Golan. A/70/82–E/2015/13. Retrieved from https://unispal.un.org/DPA/DPR/unispal.nsf/0/E40B9DC865916AEB85257E6000580750

- United Nations. (2016a). Israeli settlements in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, and the occupied Syrian Golan. A/71/355. Retrieved from http://daccess-ods.un.org/access.nsf/Get?Open&DS=A/71/355&Lang=E

- United Nations. (2016b). Report of the Special Committee to investigate Israeli practices affecting the human rights of the Palestinian people and other Arabs of the Occupied Territories. A/71/352. Retrieved from http://daccess-ods.un.org/access.nsf/Get?Open&DS=A/71/352&Lang=E

- United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia. (2017). Israeli practices towards the Palestinian people and the question of apartheid. Retrieved from https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/wp-content/uploads/downloads/201703_UN_ESCWA-israeli-practices-palestinian-people-apartheid-occupation-english.pdf

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territories. (2014). West Bank access restrictions September 2014. Retrieved from https://www.ochaopt.org/sites/default/files/Westbank_2014_Final.pdf

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territories. (2016). Occupied Palestinian territory: Fragmented lives: Humanitarian overview 2016. Retrieved from https://www.ochaopt.org/sites/default/files/fragmented_lives_2016_english.pdf

- United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. (2012). Concluding observations of the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. Israel. CERD/C/ISR/CO/14-16. Retrieved from www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/cerd/docs/CERD.C.ISR.CO.14-16.pdf

- United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East. (2015). UNRWA in Figures as of 1 January 2015. Retrieved from http://www.unrwa.org/sites/default/files/unrwa_in_figures_2015.pdf

- Vansina, J. (1985). Oral tradition as history. London, UK: Currey.

- Veracini, L. (2006). Israel and settler society. London, UK: Pluto Press.

- Veracini, L. (2008). Colonialism and genocides: Notes for the analysis of the settler archive. In A. D. Moses, (Ed.), Empire, colony, genocide: Conquest, occupation, and subaltern resistance in world history (pp. 148–161). New York, NY: Berghahn.

- von Kardoff, E. (2008). Zur Verwendung qualitativer Forschung [About the employment of qualitative research]. In U. Flick (Ed.), Qualitative Forschung: Ein Handbuch [Qualitative research: A handbook] (pp. 615–622). Reinbek bei Hamburg, Germany: Rowohlt.

- Wehr, H. (1976). Arabisches Wörterbuch für die Schriftsprache der Gegenwart und Supplement [Arabic dictionary for the contemporary written language with supplement] (4th ed.).Wiesbaden, Germany: Harrassowitz.

- Wilcock, A. A. (2006). An occupational perspective of health (2nd ed.). Thorofare, NJ: Slack.

- Winkler, M. (2006). Kritik der Pädagogik: Der Sinn der Erziehung. [Critique of pedagogy: The purpose of education]. Stuttgart, Germany: Kohlhammer.

- Wolfe, P. (2006). Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native. Journal of Genocide Research, 8(4), 387–409. doi: 10.1080/14623520601056240

- Wolfe, P. (2008). Structure and event: Settler colonialism, time, and the question of genocide. In A. D. Moses (Ed.), Empire, colony, genocide: Conquest, occupation, and subaltern resistance in world history (pp. 102–132). New York, NY: Berghahn.

- Wulf, C. (2004). Die innovative Kraft von Ritualen in der Erziehung: Mimesis und Performativität, Gemeinschaft und Reform. [The innovative power of rituals in education: Mimesis and performativity, community and reform]. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 7. Jahrgang, Beiheft 2/2004 (pp. 9–16). Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer VS.