ABSTRACT

The aim of this study was to explore the experiences of occupational disruption during a pandemic among individuals living with chronic disease, with particular attention to experiences related to managing disease(s) and routine healthcare. This qualitative descriptive study using virtual semi-structured interviews was conducted with 23 participants diagnosed with chronic disease(s) for at least 2 years, living in New Brunswick, Canada. Three overarching themes, and seven sub-themes emerged from the thematic analysis: 1) reactions (sub-themes: occupational loss and loneliness; fear and vulnerability); 2) adaptations (sub-themes: engaging in new or re-discovered occupations; prioritizing self-management; changing perspective); and 3) barriers (sub-themes: limited access to care; environmental challenges). Individuals living with chronic disease modified what they did to provide structure and purpose in response to restrictions imposed on their regular day-to-day occupations and the feelings this evoked. Notably, participants reported a heightened engagement in occupations focused on maintaining health and well-being; however, not all adaptations resulted in positive outcomes. Reactions such as fear and vulnerability influenced behavior and contributed to apprehension to seek out medical care. Changes in the environment also created barriers and challenged the participants’ ability to adapt. This research offers the first glimpse inside this occupational paradigm, to not only enhance understanding of the impact of COVID-19 on individuals living with chronic disease, but also to strengthen knowledge of what is needed to improve communication, organization, and the provision of care for individuals living with chronic disease both during a pandemic and in everyday life.

本研究旨在探讨慢性病患者在大流行病期间生活活动中断的经历,重点是与疾病治疗和常规医疗保健相关的经历。这项使用虚拟半结构化访谈的定性描述性研究,参与者是居住在加拿大新不伦瑞克省的 23 名被诊断患有慢性病至少 2 年的患者。主题分析中出现了三个总主题和七个子主题:1) 反应(子主题:活动丧失和孤独;恐惧和脆弱性); 2)适应(子主题:从事新的或重新发现的活动;以自我管理为先; 改变视角); 3) 障碍(子主题:有限的护理机会;环境挑战)。

患有慢性病的人对他们以前的活动进行了调整,以提供结构和目的来应对其常规日常活动的限制以及由此引发的感受。值得注意的是,参与者报告说,他们更多地从事以维持健康和福祉为重心的活动;然而,并非所有的适应措施都产生了积极的影响结果。恐惧和脆弱等反应会影响行为并导致对寻求医疗帮助的担忧。环境的变化也造成了障碍,挑战了参与者的适应能力。这项研究首次提供了这个活动范式的性质,不仅会加深对 COVID-19 对慢性病患者影响的理解,还会加强在流行病期间和日常生活中,对改善沟通、组织和为慢性病患者提供医疗帮助所需的知识。

El objetivo de este estudio supuso explorar las experiencias de interrupción ocupacional durante una pandemia entre personas que viven con enfermedades crónicas, poniendo especial atención a las experiencias relacionadas con el manejo de la(s) enfermedad(es) y la atención de salud habitual. El presente estudio cualitativo y descriptivo se llevó a cabo utilizando entrevistas semiestructuradas virtuales con 23 participantes, que habitan en Nuevo Brunswick, Canadá, quienes padecen enfermedad(es) crónica(s) diagnosticadas desde hace al menos dos años. El análisis temático arrojó tres temas generales y siete subtemas: 1) reacciones (subtemas: pérdida ocupacional y soledad; miedo y vulnerabilidad); 2) adaptaciones (subtemas: participación en ocupaciones nuevas o redescubiertas; priorización de la autogestión; cambio de perspectiva); y 3) barreras (subtemas: acceso limitado a la atención médica; desafíos ambientales). Para responde a las restricciones impuestas a sus ocupaciones cotidianas habituales y a los sentimientos que esto les provocaba, las personas que viven con una enfermedad crónica modificaron lo que hacían con el fin de dotarse de estructura y propósito. En particular, los participantes informaron de su mayor participación en ocupaciones centradas en el mantenimiento de la salud y el bienestar. Sin embargo, no todas las adaptaciones produjeron resultados positivos. En el comportamiento incidieron reacciones como el miedo y la vulnerabilidad, que provocaron cierta aprensión tendiente a buscar atención médica. Asimismo, los cambios ocurridos en el entorno crearon barreras y supusieron un reto para la capacidad de adaptación de los participantes. Esta investigación proporciona el primer acercamiento a este paradigma ocupacional, el cual contribuye no sólo a mejorar la comprensión del impacto de la Covid-19 en las personas que viven con enfermedades crónicas, sino también a fortalecer el conocimiento de qué se necesita para mejorar la comunicación, la organización y la prestación de atención a estas personas, tanto durante una pandemia como en la vida cotidiana.

Chronic disease, defined as “diseases that are persistent and generally slow in progression which can be treated but not cured” (Public Health Agency of Canada, Citation2013), is the leading cause of disability and death globally (Anderson, Citation2010; Lix et al., Citation2018). Commonly referred to as noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), chronic conditions account for significant healthcare utilization and cost. It is estimated that 44% of Canadian adults aged 20 years or older have at least 1 of 10 common chronic diseases: hypertension (25%), osteoarthritis (14%), mood and/or anxiety disorders (13%), osteoporosis (12%), diabetes (11%), asthma (11%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (10%), ischemic heart disease (8%), cancer (8%), or dementia (7%) (Government of Canada, Citation2019). A New Brunswick Health Council (Citation2016) report entitled The Cost of Chronic Health Conditions to New Brunswick suggested the province of New Brunswick has the highest prevalence of chronic disease in Canada, with 20% of the population having three or more chronic diseases.

It is common for individuals with chronic diseases to be constantly trying to balance the demands of their illness with their everyday lives (van Houtum et al., Citation2015). Experiencing ‘everyday’ problems (e.g., financial, housing, employment) and ‘social’ problems (e.g., family, leisure) are related to less active coping behaviours and difficulties with the ability to recognize and manage symptoms (van Houtum et al., Citation2015). The added disruption brought on by a pandemic has the potential to make this daily balancing act even more difficult.

On March 11, 2020 the World Health Organization declared a pandemic due to a global outbreak of COVID-19, an infectious disease caused by the coronavirus. This declaration set in motion preparedness and response plans all around the world. These plans were aimed at “flattening the curve” to reduce new cases of COVID-19 and thus prevent the overload of healthcare systems (Johns Hopkins University and Medicine, Citation2020). When healthcare providers are assisting with, or disrupted by, pandemic implementation plans, individuals with chronic disease often experience alterations to their regular care (Heffelfinger et al., Citation2009). As demonstrated during other pandemics, “any catastrophic outbreak of infectious disease will have profound effects on the availability and delivery of health care services and the functioning of health care institutions” (Melnychuk & Kenny, Citation2006, p. 1393); therefore it is reasonable to assume that those with chronic disease may experience changes to their regular approach to their disease management and access to routine care.

As highlighted by Blickstead and Shapcott (Citation2009), “while everybody is affected by a pandemic, everyone is not affected equally. People with compromised health face greater risks” (p. 2). Tseng (Citation2020) suggested healthcare systems need to be ready for the ‘aftershocks’ of a pandemic, one being the ‘collateral damage’ caused by the interrupted care of people who have chronic diseases. For people with chronic disease, their roles, routines, and ability to take care of themselves (e.g., eat healthy meals, exercise, take medications, attend doctor appointments), enjoy leisure pursuits (e.g., spend time with friends and family, socialize), or productively contribute to their communities (e.g., work outside the home, volunteer) can be significantly impacted or restricted when disruptions in occupations are experienced, as in the case of a pandemic (Townsend & Polatajko, Citation2007).

Humans are occupational beings. Occupation is believed to give life meaning and organize behavior, as well as be a critical determinant of health and well-being with therapeutic potential (Townsend & Polatajko, Citation2007; Wilcock, Citation2006). While some occupations may be easily adjusted or omitted, individuals can experience occupational disruption if they cannot participate in the day-to-day occupations that make up life as they know it (Townsend & Polatajko, Citation2007). Nizzero et al. (Citation2017) advocated the importance of understanding what happens when individuals are unable to participate in meaningful occupations, even transiently or temporarily, referring to this state of impaired participation as occupational disruption. To adapt during a pandemic, individuals need to change what they do to respond to their ‘new’ environment to maintain their occupational performance (Klinger, Citation2005). There is limited literature exploring occupational disruption and the adaptation that may be required during a pandemic among individuals living with a chronic disease. In addition, “while it is important to ensure identification of high risk populations for pandemic, it is equally important to identify needed supports which can mitigate social risk and minimize the impact of pandemic on populations which are typically disadvantaged in everyday life” (O’Sullivan & Bourgoin, Citation2010, p. 22).

The purpose of this study was to explore the experiences of occupational disruption during a pandemic among individuals with chronic disease. Particular attention was given to experiences related to managing disease(s) and routine healthcare. Research that explores the disruption to routines, roles, habits, and occupations and how this might affect disease management and healthcare will strengthen knowledge of the impact of COVID-19 on individuals living with chronic disease and provide needed insights to improve future practice, policy, and research.

Methods

This study used a qualitative descriptive design to explore how occupational disruption was experienced among individuals with chronic disease during the COVID-19 pandemic. Qualitative description is a practical qualitative approach often used to answer questions for clinical practice and policy. It enables a researcher to get clear-cut answers to research questions, as well as supporting the development of a detailed, yet uncomplicated, synopsis of an experience or occurrence (Asbjoern Neergaard et al., Citation2009; Sandelowski, Citation2000). Qualitative description offers a health researcher an approach to describe “lived experiences and aspects of experiences of health and illness” (Willis et al., Citation2016, p. 2). Ethics approval was obtained in May 2020 from the University of New Brunswick, File #012-2020. This study was jointly funded by the New Brunswick Innovation Foundation, the New Brunswick Health Research Foundation, and the Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency, Grant # COV2020-029.

Setting and context

Similar to other provinces in Canada and countries across the globe, New Brunswick declared a state of emergency on March 19, 2020 to help contain the spread of COVID-19 (Government of New Brunswick, Citation2020b). As part of these measures, people were instructed to stay at home and only leave for essential needs. Many business and healthcare providers had to modify the way in which they offered services, if at all. As part of the pandemic plan, healthcare services deemed not medically urgent were postponed or cancelled and virtual consultations with care providers (instead of face-to-face) were encouraged (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, Citation2020; Horizon Health, Citation2020). As the weeks passed, the Government of New Brunswick (Citation2020a) slowly implemented a phased plan to relax some of the restrictions initially implemented, with the understanding that if COVID-19 cases had a significant increase, the phases would regress. During the time of data collection (May-June 2020) the province eased restrictions from phase 2 (e.g., allowing outdoor public gatherings with physical distancing with no more than 10 people; resumption of some elective surgeries and other non-emergency health services), to phase 3 (e.g., allowing gatherings with physical distancing with no more than 50 people; additional elective surgeries and non-emergency healthcare services, non-regulated health professionals; opening of gyms and swimming pools).

Participant selection and recruitment

This study used purposeful sampling, which involved identifying a diverse sample of individuals with chronic disease from across the province of New Brunswick, Canada. Individuals with chronic disease were eligible to participate if they self-reported: 1) they lived in the same city in New Brunswick for at least 2 years prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and 2) they lived with a diagnosed chronic disease for at least 2 years. Sampling also took into consideration geography, living situation, disease type(s)/severity, and age. This sampling approach, based on the intent to select a variety of information-rich cases, ensured individuals had prior experience living with a chronic disease and using local healthcare services; had established routines and occupations related to their chronic disease; and maximized the variation in the sample. Participants were excluded if they: 1) could not speak either English or French; 2) refused to give consent to participate; or 3) were unable to participate in a virtual interview (phone or video conference).

Participants were recruited through promotional activities over social and traditional media. To maximize the variation of participants throughout the recruitment phase, social media was directed to various locations across the province and through various health charities and organizations. The researchers also electronically distributed recruitment flyers to colleagues and friends who further shared the flyers through their networks. Snowball sampling was also used with each interviewed participant, to support study recruitment. The participants were offered a token honorarium as a gesture of appreciation. Twenty-five individuals were recruited and screened for participation. Two were excluded due to not meeting the inclusion criteria.

Data collection

Individual interviews using an interview guide containing open-ended questions and associated probes (see appendix), and lasting approximately 60 minutes, were used to explore the experiences of occupational disruption. The interview questions were developed from the researchers’ clinical experiences as well as literature on occupation/occupational disruption. The interview guide was field-tested with two individuals who met the inclusion criteria (but were not part of the study sample) to ensure the questions were clear and pragmatically sequenced. Written consent was obtained prior to each interview and re-confirmed verbally on interview completion. All interviews were conducted virtually over a video conferencing service, between May 14th and June 29th, 2020. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. Field notes were also compiled during and immediately after each interview to capture observations and impressions. To maintain confidentiality, all data were de-identified directly after the interview process and pseudonyms assigned to each participant.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis outlined by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) guided data analysis for this study. The six phases of this approach supported the identification of codes; the recognition of relationships between codes and patterns across the data set; the development of themes; and the organization of the data in rich detail. This approach complemented the intention of qualitative description to generate a thorough description, without being tied to a specific structure or theory (Asbjoern Neergaard et al., Citation2009). Three members of the research team, with diverse backgrounds (occupational therapy, nursing, and sociology), independently coded selected transcripts. These codes were discussed at length and refined among the three co-authors, then merged into a code table which comprised code names, descriptions, and examples from the data. These codes were then explored for similarities and differences using a visual mapping process to identify and compare emerging themes across the data. An additional summary table including the emerging themes and extracted quotes was developed to enhance organization and discussion of the findings. Data collection was concluded when there were no significant new ideas or themes identified. This summary table was also provided to each participant, and they were invited to provide feedback on the initial description and interpretation to enhance trustworthiness. Nine participants provided feedback and they indicated the summary was an accurate account of their experiences. NVivo was used to assist in data storage and analysis.

Findings

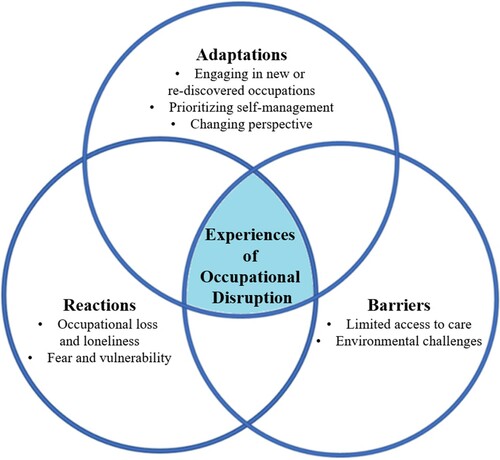

The final sample included 23 participants living with chronic disease from across the province. General demographics (see ), as well as individualized characteristics (see ) provide a comprehensive summary of the participants included in this study. Excerpts from participant transcripts were used to assist in the transparency of the analysis, as well as to add richness to the presentation of the findings. Seven interconnected themes emerged based on stories and experiences frequently shared by the participants and were mapped under three overarching themes: 1) reactions; 2) adaptations; and 3) barriers (see ). Each theme name is expressed using a direct quote to convey the essence and overall meaning.

Figure 1. Experiences of occupational disruption during a pandemic among individuals with chronic disease

Table 1. Participant Demographics

Table 2. Participant Characteristics

Reactions

The first overarching theme, reactions, captures the feelings experienced by the participants in response to the occupational disruption, which often influenced and drove their behavior. The two sub-themes include: 1) occupational loss and loneliness; and 2) fear and vulnerability.

Occupational loss and loneliness: “I feel left out … like I’m not connected” (Tammy)

This theme depicts the feelings of occupational loss and loneliness described by the participants. All participants shared experiences of missing the connectedness once felt through occupations and interactions with other people and being in control to come and go as they wanted. As Olivia plainly explained: “I only go to Costco [supermarket]. That’s it! I go once a week, and that’s everything!”. Tammy likened her experience to being held captive, “being trapped in your house in the colder months was very difficult for sure … as much as I felt vulnerable going anywhere, I still missed going everywhere, so I felt … kind of like a prisoner”. Similarly, Claire expressed prior to the pandemic she “was just free to go more”. Faye shared even though she is an “introvert”, it did not prepare her for the loneliness she experienced.

I’ve been always very happy with just you know reading a book or whatever but I have to have a certain amount of social contact each week or I just really feel um, abandoned … I don’t know how to really describe the feeling but it’s just, since I live alone, I just feel so isolated.

Most participants shared a loss of routines, roles, and occupations that were either limited or non-existent. Rose described the loss she felt for occupations she regularly participated in, especially the connectedness it brought her: “It’s social interactions … I really miss going to church and being in the choir and all those”. However, a few participants, including Erin, shared the degree of loss they felt in their day-to-day occupations “hasn’t changed a lot” as compared to prior to the pandemic due to the relatively sedentary lifestyle resulting from their medical condition(s).

While many participants were able to find new or different occupations to replace those lost, some found it more challenging to fill the void when they were unable to engage in occupations that once brought them meaning and purpose. Betty explained: “volunteer work is, that’s where I’m missing the gap right now … haven’t found a way to replace that, those hours that I spent volunteering”.

Fear and vulnerability: “I really felt in some ways that I’m walking with a target on my back” (Tammy)

This theme illustrates the fear and vulnerability described by those living with chronic disease due to feeling their medical condition(s) made them higher risk than those without chronic disease if they contracted COVID-19. As explained by Violet, “I'm staying home because of my low immune system. I can’t afford to get this”. Donna shared how her previous experiences with chronic disease had made her more frightened and cautious:

I think fearful is a fair word, I think that, that’s a very fair word because, you know, I’m very vigilant and very aware of the risk, and um, you know I’ve experienced lung infections in the past that were very severe … so I am very hypervigilant and aware of it.

Most participants described how they modified their occupations by planning ahead, doing them less often than before the pandemic (e.g., getting groceries every 2-3 weeks versus weekly), or even avoiding them altogether when they could, to minimize their risk and lessen their stress. Those fortunate enough to have others around to help relied more heavily on them, through giving up their own occupations, roles, and responsibilities. Like many of the participants, Rose shared her experience of the role reversal that happened in her house: “He’s going out doing the things I used to … I used to do the food shopping, the post office, the pharmacy, bank, everything, but … we decided now that he was less at risk”.

Not only were these fears and feelings of vulnerability directing day-to-day occupations, they also contributed to the apprehension of seeking medical care. Most participants did not want to go into a healthcare building, feeling they would be in contact with other ‘sick’ people and it would put them at higher risk. Grace explained, “I don’t wanna go to a hospital, I don’t wanna go anywhere like that right now … . Because, well, if you’re sick, that’s where you’re going to go – to the hospital”. Due to these fears, many put off seeking care when they would normally acquire it. Helen shared, “I would have gone and gotten a tetanus shot, but because of the pandemic, I decided not to, um, and I just kept watching it”. Iris didn’t know if she would even been seen if she showed up in the emergency room:

I would have gone in, I would’ve called a friend and I would have probably gone in to the outdoor with symptoms like that [cold sensation going down left side of body and chest pain], but this time I just thought – they’re so overworked, I don’t even know if you can get into the ER for anything right now, yeah I’m just gonna sit here and wait it out.

Some participants even tried to modify the type of occupations they engaged in to minimize their chances of exacerbating their condition or getting hurt, so they would not have to go to the hospital. Helen revealed, “in all honesty I’ve tried not to do too many outrageous things, because I don’t want to have to go to the ER or anything like that”.

Adaptations

This overarching theme captures how the participants adapted their occupations in response to the disruption to enhance occupational performance. The three sub-themes include: 1) engaging in new or re-discovered occupations; 2) prioritizing self-management; and 3) changing perspective.

Engaging in new or re-discovered occupations: “Trying to make up for what we were doing before” (Betty)

This theme describes how participants adapted to their new way of living during the pandemic, and the limitations it imposed, through engaging in new or re-discovered occupations. All participants shared stories of how they adjusted and re-established connections with their social supports and friends via phone and/or virtually. Paula explained, “I did online stuff … Zoom, I was just so excited to see some of these people”. Many also shared they had a new appreciation for time spent with friends. Technology facilitated connection with others, with Jack using both the internet and phone to stay connected with others, but “it’s not the same”.

Others engaged in different occupations to replace occupations they were unable to do and to provide structure and purpose in their day. Mary’ “son has found these YouTube videos on Korean recipes. We made souffles, and all this crazy stuff, so yeah … him and I are having lots of fun cooking”. Tammy explained how she reconnected with her creativity:

I’ve done a lot of puzzles … . I do paint … I guess it’s brought out my creative side again which I feel like has kind of gone away a little bit, so it was nice to kind of reconnect with that part.

Most participants also felt the expertise and skills they developed from living with the ups and downs of chronic disease (including routines and habits related to managing their disease) enabled them to more easily adjust and adapt to changes due to the pandemic. Kelly described how she became “pretty adaptable” because of her chronic disease:

You’ll have a plan and then it will have another plan when that day comes … that’s kind of what this whole thing has been … trying to live and keep going while dealing with other stuff is essentially what you do with a chronic disease and kind of what this whole pandemic has been. People trying to live their lives but then taking on other roles that they weren’t doing before.

Prioritizing self-management: “Start relying more on myself … basically start thinking OK, what if my doctors just disappeared?” (Qiana)

This theme depicts how most participants with chronic disease described being more attentive to self-managing their disease throughout the pandemic. Qiana explained she needed to “start relying more on myself … I gotta know my body more and that’s what I’ve been doing”, while Grace “just had to think of other ways to – to make myself healthy”. Most participants described a heightened interest in better managing their disease and being more accountable and attentive to their medical conditions and health while having limited access to healthcare providers, such as their family doctor, physiotherapist, or massage therapist. Nancy shared how she managed her arthritis during the pandemic when access to her healthcare providers was limited:

I exercise … I take long hot baths, I meditate, I walk, … I don’t sit, because if I sit down everything kind of seizes up right, so I just keep moving around … that’s what I do because there’s nobody, there wasn’t anything to loosen anything back up right, so it was up to me.

I’m checking my temperature and my peak flow meter every day, to make sure my lung function was good. Um, trying to keep track of uh, you know doing some cardio, getting out and walking more to try to strengthen my lungs.

Some participants also had the mindset that they wanted to “make sure you’re as strong as possible because if you do get COVID-19, it’s going to work a lot better if you don’t have a chest infection already brewing” (Helen). Some participants, including Abby, shared an enhanced commitment to self-management in the future: “I think I'll be more attentive than I was before … the new normal would be taking better care of myself, being more attentive”.

The participants also reported an enhanced focus on emotional and mental well-being. Abby felt the pandemic had less “impact on my physical health, but I do feel it has an impact on my emotional health”. As mentioned in previous themes, all participants expressed a degree of isolation and loneliness and most described higher levels of anxiety and stress. While some felt they were a little more prepared for the isolation than others, due to a more secluded lifestyle, everyone described the burden isolation had on their mental health and well-being during the pandemic. Most participants were more mindful about engaging in occupations that were specifically directed at self-managing and supporting their mental health, such as meditation, walks, time in nature, yoga, and taking more time for themselves. Paula felt the pandemic reminded her how important it was to engage in occupations to support her mental wellness as part of her self-management, stating, it “drove it home more how important it is to keep up my spiritual practices and be really diligent and look for those online opportunities … because it really has helped me”.

Changing perspective: “I am not worrying about that because, if it gets done, it gets done, if it doesn’t, it doesn’t” (Nancy)

This theme illustrates how participants described a re-evaluation of what was important to attain better occupational balance. Tammy shared she appreciated the slower pace and the newfound perspective the pandemic offered, suggesting it made her look at what is really needed and important, “I actually like how everything has kind of slowed down. And I don’t need it today, I can wait ‘till tomorrow”. Many participants described how the pandemic allowed them to appreciate the little things that are often overlooked due to the busyness of life and being over scheduled. This allowed for more time to discover new occupations, as well as more “me” time. Kelly explained how she has more time to appreciate and enjoy new things, “sitting outside, like just enjoying being outside in the yard, like before we never really had that chance, everything was so busy between the kids and just life”. Olivia shared how she tried to make every day special, “I’ve had lobster every week because, there’s a pandemic! … I want to keep my life really happy!”

Many participants also shared that they lowered the priority of occupations they perceived as not being as necessary, such as chores around the house. Mary explained:

Laundry, like as long as we have clothes – some clothing … dishes, like we’ll get to them … as long as we’re outside just enjoying the elements, outside and being together. Yeah, like no one’s coming in there, it’s a bit messy – so what? We’ll clean it tomorrow, you know?

Barriers

This overarching theme captures how the disruption experienced in healthcare and changes in the environment created obstacles to occupational performance during the pandemic. The two sub-themes include: 1) limited access to care; and 2) environmental challenges.

Limited access to care: “I feel like I’m kind of in limbo” (Iris)

This theme captures experiences of health uncertainty described by all the participants. Cancelled healthcare appointments and limited access to needed healthcare providers, such as with family doctors, hospital clinics (labs and diagnostic testing), specialists, physiotherapists, and massage therapists created a sense of “limbo”. Many felt they had little, or no, communication with their healthcare providers regarding when, if, or how their healthcare needs would be addressed. Wendy expressed, “everything was up in the air. And it was extremely stressful because I’m like what’s gonna happen next? Because people with illnesses need some kind of order and structure”.

Many participants shared concerns of not having access to care when they needed it, and worried about backlogs when the health systems started to open back up. Iris shared:

The things that I needed, everything just kind of stopped, so I’m just kind of – like I’m supposed to be getting in to a neurologist and I was at the bottom of the list, now I can only imagine where I’m at on the list, so I don’t even know. Again, I need to get in to the arthritis specialist, I don’t know when those things will start to get moving or anything like that … I can’t see my doctor. He’s not seeing patients, he’s just doing phone calls, so I did call about my hands being worse and he just, you know, was like – ‘Well, we’ll see what we can do.’

Some who were able to access care with their family physicians in a modified way (e.g., over the phone, or over video call) felt this approach did not provide the same quality of care as an in-person visit when they required a physical assessment (e.g., listen to lungs, take blood pressure). As explained by Liam:

I am asthmatic … I rely on these doctors to make sure everything’s alright with me … when I’m on by the phone, how they gonna do that, like am I supposed to check my own lungs now?

She used to check like my joints and would tell me, ‘Oh this one is warm … You have a little inflammation here and there’ … And now, I’m having to try to explain to her on the phone, but sometimes … she’ll tell me my elbows are really warm … but I didn’t feel anything. Kinda hard for me to explain to her, well I don’t feel anything but doesn’t mean that there’s nothing there.

However, for basic health needs, like refills on prescriptions, virtual care was often preferred as it was more efficient and less onerous than attending an appointment in-person (e.g., transportation, time, etc). As Kelly explained:

You don’t actually have to see the doctor, especially for situations where it’s like just prescription renewals, it would be wonderful. Cause sometimes like if you’re having a bad day, it’s hard, it takes a lot of energy to get up, get ready, go to the doctor, and then they’re always behind so you sit there forever and then it’s exhausting, so if you could just have them call you, then I think that’d be great.

There was only me and one other person in the room, which in a way I kind of liked because it was so efficient and streamlined. It was just one after the other. Everybody knew what they were supposed to do. It was less hectic, less people, less chaotic, I actually liked that.

Environmental challenges: “I have no control over my environment” (Nancy)

This theme illuminates how the changes in the environment, as experienced by the participants, often made it more difficult to adapt and support occupational performance and wellness. Many participants described how their physical space, now being limited to house or apartment, made it more challenging to stay active and/or access resources they once did to support their health and wellness (e.g., fitness classes, limited equipment, less space to move around). Ursula shared:

If I were gonna go for a run, I would go to the civic centre to run around the track. I rarely run outside partially because of the allergies … this is a bad time of year and if you’re on a run you need to breathe and so it’s not the best time to be exercising outside.

I don’t think I’m getting as much exercise. I always used to do Tai Chi twice a week and I haven’t been able to do that, well I-I-I do it, you know, I do some of the exercises, the warm up exercises but I don’t remember the set, so I can’t go through the whole set … instead of you know having that four hours of exercise a week, I’m probably getting you know a half-an hour.

Some participants who continued to work, either from home or at an office, expressed challenges with additional demands on their time, or new or different roles they had to balance. Tammy shared, “my routine is all messed up and I’m not where I feel like I should be and I’m in this room by myself all day long”. Those who worked from home, or had partners and children at home, also had to adapt to changes in routines and structure, as well as less than ideal physical working conditions and additional family demands. Kelly explained:

I somewhat had a routine, and was able to fit in like doing my stretches and stuff … that’s all fallen apart cause my husband’s working from home now, my kids are here, I’m trying to do schoolwork with them. Everyone’s a little on edge.

Precautionary pandemic changes to essential services, such as physical distancing/less contact, access to shopping centers limited to one person per family at a time, bagging your own groceries, and no shopping carts created additional stress and challenges for those with physical limitations who depend on such supports to function independently, or with assistance (e.g., children/spouse help carry groceries, cart needed to mobilize through store and carry heavy items; dependent on store employees for informal help). Qiana explained, “people aren’t helping anymore. People are scared to help”. She shared how these precautionary changes had a substantial impact on her occupational performance:

My hands are pretty awful … . I go to Irving [gas station/convenience store] to buy my bread and my bananas and I get a plastic bag passed to me and then I’m trying to open the bag with my hands and I’m fumbling and I just get upset.

Discussion

The findings from this study demonstrate the dynamic interconnection of person, occupation, and environment discussed in various occupational performance models (Baum et al., Citation2015; Law et al., Citation1996; Townsend & Polatajko, Citation2007). The study themes arose and naturally merged into three overarching themes: reactions, adaptations, and barriers, which further exemplifies how individuals interact with their environment through occupation (Townsend & Polatajko, Citation2007). The Canadian Model of Occupational Performance and Engagement (CMOP-E) endorses that occupation is the “the bridge that connects person and environment” (Townsend & Polatajko, Citation2007, p. 23) and this study illustrates this concept. Individuals with chronic disease shared their reactions to the occupational disruption during the COVID-19 pandemic and how they adapted through occupation to the challenges and barriers imposed by their environment (i.e., isolation, healthcare closures, changes to physical spaces).

While this is to our knowledge the first exploration of occupational disruption during a pandemic of any cohort, the findings of this study share many similar experiences and findings related to occupational disruption, irrespective of context. The reactions experienced by the participants, such as loss, loneliness, fear, and vulnerability are not unique to a pandemic, and further reinforce the significance of occupational participation. These feelings have been demonstrated in other cases of occupational disruption caused by illness or injury, such as traumatic brain injury (Cotton, Citation2012), arthritis (McDonald et al., Citation2012), and repetitive strain injuries (McCready & Reid, Citation2007); and significant events such as immigration (Gupta, Citation2012), house fire (Rosenfeld, Citation1989), retirement (Walker & McNamara, Citation2013), and natural disasters (Sima et al., Citation2017). Nizzero et al. (Citation2017) suggested that emotional responses such as uncertainty, anxiety, and vulnerability are common when experiencing occupational disruption due to the loss of occupations and/or social connections, as well as feeling a lack of control.

In this study, all responses were evident and drove participant behaviors including planning ahead, relying on others, and giving up or modifying roles, responsibilities, and occupations. What is both noteworthy, and worrisome, is these reactions also influenced health seeking behavior. As exhibited in this study, many participants expressed they would not go into a healthcare building or seek out medical care to avoid coming into contact with COVID-19. This fear also appeared to contribute to the enhanced focus on self-management, where participants wanted to be “as strong as possible” if they contracted COVID-19 to minimize the risk of having a compromised immune system.

Consistent with the occupational disruption literature (Gupta, Citation2012; McCready & Reid, Citation2007; Morville & Erlandsson, Citation2013; Nizzero et al., Citation2017; Sima et al., Citation2017; Suto, Citation2013; Walker & McNamara, Citation2013), participants shared multiple examples of how they modified what they did to provide structure and purpose in response to the restrictions imposed on their regular day-to-day occupations and the feelings this evoked. Adjusting and re-establishing connections with their social supports, re-prioritizing how they spent their time, and engaging in alternative or modified occupations to address the things they were unable to do or didn’t have access to (e.g., healthcare), allowed them to adapt to these occupational challenges. Of particular note, participants reported engagement in occupations that were specifically focused on maintaining health and well-being (i.e., disease self-management and mental health).

This renewed focus appeared to be motivated by not only fear and vulnerability, as previously suggested, but also by the participants’ need to have control of their own physical and emotional well-being while dealing with the pandemic, and limited access to healthcare supports and resources. Similar experiences have been shared by women with breast cancer, where they used occupation to build routine, manage stress, and control their own health (Palmadottir, Citation2010), as well as by men seeking asylum, where they engaged in occupation to build structure and routine to keep “distress at bay” (Morville & Erlandsson, Citation2013, p. 218). This is congruent with the occupational science literature suggesting occupation not only provides the mechanism to meet human needs and adapt to environmental demands but is also needed to maintain health and well-being (Wilcock, Citation2006).

These various examples of how participants adapted to the disruptions caused by the pandemic are in keeping with the scoping review by Nizzero et al. (Citation2017), where they suggested adaptive strategies reported in the occupational disruption literature fell into three categories: modifying occupations, engaging in new occupations, or trying to maintain structure and routine. They also concluded strategies for occupational adaptation (i.e., how individuals manage disruption) can be both adaptive (enabling a positive outcome or lessening a negative experience) or maladaptive (contributing to a negative outcome, or not lessening a negative experience). While most experiences shared in this study appeared to allow participants to maintain or improve their occupational participation and performance, their hesitation to seek out medical care, even if it was perceived to minimize their risk, could also be considered maladaptive due to the potential for harm of not seeking care when and if needed. It is also noteworthy that many participants perceived they were “pretty adaptable” to the disruptions they had to face. This finding may be explained by the occupational adaptation framework by Schkade and Schultz (Citation1992), which suggests the adaptive response to an occupational challenge is evaluated for subsequent experiences within the cycle and these learnings are then integrated or adjusted for future challenges. The previous expertise and skills the participants developed from living with the ups and downs of chronic disease, including routines and habits related to managing their disease, appeared to enable them to more easily adjust and adapt to their current situation.

As previously seen in the literature (Morville & Erlandsson, Citation2013; Sima et al., Citation2017), participants experienced many occupational challenges and barriers when disruptions were imposed by their environment. In particular, the imposed pandemic preparedness changes, such as physical distancing/less contact, limited access to healthcare, and restricted entry and resources at some shopping centers often created additional, or new, obstacles for those with chronic disease. These instances are overt examples of how the environment can greatly impact occupational participation and performance. Bambra and colleagues (Citation2020) cautioned that due to the already existing social and economic inequities of those living with chronic disease, COVID-19 has the potential to have a negative effect on their health conditions and add to their disease burden. As demonstrated in this study, changes implemented by government with the intention to protect the public can often have unintentional effects on those more vulnerable. It is often the case that individuals living with disease and disability are not top of mind when dealing with emergencies, such as in a pandemic; however it is critical to ensure the needs of those living with disease and disability are understood and COVID-19 plans are tailored appropriately (Kuper et al., Citation2020). Campbell and colleagues (Citation2009) suggested pandemic plans often “lack consistency of approach, depth, or evidence of safeguards and effective implementation” (p. 295), as well as underestimating the degree of planning and coordination that needs to happen to ensure risk mitigation, accommodation, and integration of everyone in society.

Implications for practice, policy, and research

The findings of this study add valuable insights and understanding of the experiences of occupational disruption within the unique context of the COVID-19 pandemic to inform policy, practice, and future research. Firstly, this study identifies how reactions to this occupational disruption influenced behavior and contributed to apprehension to seek medical care. This highlights the need for better communication, awareness, and research around what precautionary strategies are actually in place to protect those using the healthcare system and the capacity available to treat non COVID-19 related medical issues. If this maladaptive strategy of avoidance of seeking healthcare is not addressed, it could cause significant harm.

Secondly, this research uncovered the uptake in occupations that were specifically focused on maintaining health and well-being. Authors of the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion advocated that to achieve physical, mental, and social well-being, individuals not only need to adapt (as was demonstrated in this study), but they also need social supports and resources to assist with the behavior change (World Health Organization, Citation1986). Research exploring patient self-management needs in this new COVID-19 environment and policy to support practice (e.g., what can be done to support self-management in different environments), would further enhance adaptive strategies to regain control, build routines, and manage wellness. This could also be an opportune time for professionals to intervene to support those interested in changing behaviors.

Lastly, this study underscores the barriers and occupational challenges created for individuals with chronic disease due to pandemic preparedness changes in their environment. Further exploring these obstacles and involving those with lived experience in policy development and implementation (Kuper et al., Citation2020) would ensure their voices are heard, help mitigate risk, and ultimately improve occupational performance.

Limitations

Data collection was limited to individuals from various locations across the province of New Brunswick, Canada living with chronic disease for at least two years. Participants’ health conditions, demographics, and characteristics also ranged greatly (i.e., geography, education, income, employment, living situation, impact of disease on day-to-day occupations, and number of years with chronic disease). Even though this diversity allowed for the exploration of shared experiences across a broad range of cases, which contributed to their significance (by emerging out of heterogeneity), the findings cannot be generalized to all places or people living with chronic disease. There was limited variation in the gender of the participants, with only two males participating compared to 21 females. While the researchers did not detect any notable differences in experiences shared between the sexes, this unbalanced representation may have influenced the findings. Additionally, the length of time living with a chronic disease for the majority of participants was greater than 15 years; individuals with less familiarity managing a chronic disease may experience occupational disruption during a pandemic quite differently.

This study was also conducted during an earlier phase of the pandemic and only captures experiences of occupational disruption up to this point in time. As well, even though data collection happened over a relatively short period of time (six weeks), when considering the circumstances of things changing on a fairly rapid basis, this may have influenced the experiences shared by participants between the first interview and the last. One cannot assume that as the pandemic evolved and the environment potentially changed, the experiences of occupational disruption did not change. Research using a longitudinal perspective might further illuminate how experiences of occupational disruption change over the course of a pandemic to inform future policy, practice, and research.

Conclusion

This study sheds light on the under-studied topic of occupational disruption that has not, up until now, been explored in relation to a pandemic (Nizzero et al., Citation2017). It illustrates how individuals living with chronic disease used occupation to interact with and adapt to the occupational disruption experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic to support their occupational performance. Individuals living with chronic disease modified what they did to provide structure and purpose in response to restrictions imposed on their regular day-to-day occupations and the feelings this evoked. Of particular note, participants reported a heightened engagement in occupations focused on maintaining health and well-being; however, not all adaptations led to a positive outcome. Reactions, such as fear and vulnerability influenced behavior and contributed to an apprehension to seek out medical care. Changes in the environment also created barriers and challenged the ability of participants to adapt. This research offers the first glimpse inside this occupational paradigm, to not only enhance understanding of the impact of COVID-19 on individuals living with chronic disease, but also to strengthen knowledge of what is needed to improve communication, organization, and provision of care for individuals living with chronic disease both during a pandemic and in everyday life. These insights will inform efforts to better support and enhance engagement in occupation during similar events.

Declaration of Conflicting Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We honour and thank the Wəlastəkewiyik (Maliseet), Mi’Kmaq, and Passamaquoddy peoples as our community partners and traditional inhabitants of the lands of the province of New Brunswick, where this research was conducted. We formally thank and acknowledge the participants in this study for their willingness to share their experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thanks also to Poppy Jackson and Kaelin Barry for transcription support and feedback.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, G. (2010). Chronic care: Making the case for ongoing care. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/reports/2010/rwjf54583

- Asbjoern Neergaard, M., Olesen, F., Andersen, R. S., & Søndergaard, J. (2009). Qualitative description; The poor cousin of health research? BMC Medical Research Methodology, 9, 52.

- Bambra, C., Riordan, R., Ford, J., & Matthews, F. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2020-214401

- Baum, C. M., Christiansen, C. H., & Bass, J. D. (2015). The Person-Environment-Occupation-Performance (PEOP) model. In C. H. Christiansen, C. M. Baum, & J. D. Bass (Eds.), Occupational therapy: Performance, participation, and well-being (4th ed., pp. 49–55). Slack.

- Blickstead, J. R., & Shapcott, M. (2009). When it comes to pandemics, no one can be left out. Wellesley Institute. https://www.wellesleyinstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/pandemicpolicy2009.pdf

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Campbell, V. A., Gilyard, J. A., Sinclair, L., Sternberg, T., & Kailes, J. I. (2009). Preparing for and responding to pandemic influenza: Implications for people with disabilities. American Journal of Public Health, 99(S2), 294–300. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.162677

- Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. (2020, March 17). Patients can now have virtual appointments with their family doctor. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/new-brunswick/public-health-doctor-s-appointments-virtual-covid-19-1.5500953

- Cotton, G. S. (2012). Occupational identity disruption after traumatic brain injury: An approach to occupational therapy evaluation and treatment. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 26(4), 270–282. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/07380577.2012.726759

- Government of Canada. (2019). Prevalence of chronic diseases among Canadian adults. Public health agency of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/chronic-diseases/prevalence-canadian-adults-infographic-2019.html

- Government of New Brunswick. (2020b, March 19). State of emergency declared in response to Covid-19. https://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/news/news_release.2020.03.0139.html

- Government of New Brunswick. (2020a). NB’s recovery plan. https://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/corporate/promo/covid-19/recovery.html

- Gupta, J. (2012). Human displacement, occupational disruptions, and reintegration: A case study. World Federation of Occupational Therapists Bulletin, 66, 27–29.

- Horizon Health. (2020, March 16). COVID-19: Cancellation of elective surgeries and ambulatory care clinics. https://en.horizonnb.ca/home/patients-and-visitors/coronavirus-(covid-19)/covid-19-cancellation-of-elective-surgeries-and-ambulatory-care-clinics.aspx

- Heffelfinger, J. D., Patel, P., Brooks, J. T., Calvet, H., Daley, C. L., Dean, H. D., Edlin, B. R., Gensheimer, K. F., Jereb, J., & Kent, C. K. (2009). Pandemic influenza: Implications for programs controlling for HIV infection, tuberculosis, and chronic viral hepatitis. American Journal of Public Health, 99(S2), S333–339. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.158170

- Johns Hopkins University and Medicine. (2020). New cases of COVID-19 in world countries. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/new-cases

- Klinger, L. (2005). Occupational adaptation: Perspectives of people with traumatic brain injury. Journal of Occupation Science, 12(10), 9–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2005.9686543

- Kuper, H., Banks, L. M., Bright, T., Davey, C., & Shakespeare, T. (2020). Disability-inclusive COVID-19 response: What it is, why it is important and what we can learn from the United Kingdom’s response [version 1; peer review: 2 approved]. Wellcome Open Research, 5(79). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15833.1

- Law, M., Cooper, B. A., Strong, S., Stewart, D., Rigby, P., & Letts, L. (1996). The person-environment-occupation model: A transactive approach to occupational performance. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63, 9–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/000841749606300103

- Lix, L. M., Ayles, J., Bartholomew, S., Cooke, C.A., Ellison, J., Emond, V., Hamm, N., Hannah, H., Jean, S., LeBlanc, S., Paterson, J.M., Pelletier, C., Phillips, K., Puchtinger, R., Reimer, K., Robitaille, C., Smith, M., Svenson, L. W., Tu, K., VanTil, L. D., Waits, S., & Pelletier, L. (2018). The Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System: A model for collaborative surveillance. International Journal of Population Data science, 3(3), 5. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.23889/ijpds.v3i3.433

- McCready, S., & Reid, D. (2007). The experience of occupational disruption among student musicians. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 22(4), 140–146.

- McDonald, H. N., Dietrich, T., Townsend, A., Li, L. C., Cox, S., & Backman, C. L. (2012). Exploring occupational disruption among women after onset of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Research, 64(2), 197–205. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20668

- Melnychuk, R. M., & Kenny, N. P. (2006). Pandemic triage: The ethical challenge. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 175(11), 1393–1394. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.061322

- Morville, A. L., & Erlandsson, L-K. (2013). The experience of occupational deprivation in an asylum centre: The narratives of three men. Journal of Occupational Science, 20(3), 212–223. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2013.808976

- New Brunswick Health Council. (2016). The cost of chronic health conditions to New Brunswick. https://nbhc.ca/sites/default/files/publications-attachments/June202016_The20Cost20of20Chronic20Health20Conditions20to20NB20-20FINAL.pdf

- Nizzero, A., Cote, P., & Cramm, H. (2017). Occupational disruption: A scoping review. Journal of Occupational Science, 24(2), 114–127. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2017.1306791

- O’Sullivan, T., & Bourgoin, M. (2010). Vulnerability in an influenza pandemic: Looking beyond medical risk. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282817477_Vulnerability_in_an_Influenza_Pandemic_Looking_Beyond_Medical_Risk

- Palmadottir, G. (2010). The role of occupational participation and environment among Icelandic women with breast cancer: A qualitative study. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 17(4), 299–307. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/11038120903302874

- Public Health Agency of Canada. (2013). What are chronic diseases? Canadian best practices portal. https://cbpp-pcpe.phac-aspc.gc.ca/chronic-diseases/

- Rosenfeld, M. S. (1989). Occupational disruption and adaptation: A study of house fire victims. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 43(2), 89–96. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.43.2.89

- Sandelowski, M. (2000). Focus on research methods: Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing and Health, 23(4), 334–340. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-240x

- Schkade, J. K., & Schultz, S. (1992). Occupational adaptation: Toward a holistic approach for contemporary practice: I. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 46(9), 829–837. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.46.9.829

- Sima, L., Thomas, Y., & Lowrie, D. (2017) Occupational disruption and natural disaster: Finding a ‘new normal’ in a changed context. Journal of Occupational Science, 24(2), 128–139. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2017.1306790

- Suto, M. (2013). Leisure participation and well-being of immigrant women in Canada. Journal of Occupational Science, 20(1), 48–61. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2012732914

- Townsend, E., & Polatajko, H. (2007). Enabling occupation II: Advancing occupational therapy vision for health, well-being and justice through occupation. CAOT Publications ACE.

- Tseng, V. [@VectorSting]. (2020, March 30). Health footprint of pandemic graph [tweet]. https://twitter.com/VectorSting/status/1244671755781898241

- van Houtum, L., Rijken, M., & Groenewegen, P. (2015). Do everyday problems of people with chronic illness interfere with their disease management? BMC Public Health, 15, 1000. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2303-3

- Walker, E., & McNamara, B. (2013). Relocating to retirement living: An occupational perspective on successful transitions. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 60(6), 445–453. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1440–1630.12038

- Wilcock, A. A. (2006). An occupational perspective of health (2nd ed.). Slack.

- Willis, D. G., Sullivan-Bolyai, S., Knafl, K., & Cohen, M. Z. (2016). Distinguishing features and similarities between descriptive phenomenological and qualitative description research. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 38(9), 1185–204. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945916645499.

- World Health Organization. (1986). Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en/

- World Health Organization. (2020, March 11). WHO characterizes COVID-19 as a pandemic. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen

Appendix

Interview guide

Can you share with me what your day-to-day activities were like related to managing your chronic disease before the pandemic? (Probe: Think about your routines, roles, healthcare)

Can you describe how your day-to-day activities related to managing your chronic disease have changed since the pandemic? (Probe: In what ways did these changes evolve over time during the pandemic?)

What are/were some of the most significant changes that you had to confront, or adapt to, during the pandemic to manage your chronic disease? (Probe: Describe any supports/processes you have/had in place to help)

Do you think how you have managed your chronic disease during the pandemic has changed how you will manage your condition in the future, or are these changes only temporary? (Probe: Please explain)

Can you describe what has helped you to manage your chronic disease during the pandemic?

Can you describe any barriers you have faced when accessing supports, health care, or self-managing your chronic disease during the pandemic?

What, if anything, would you change about the care you received for your chronic disease during the pandemic?

Describe what changes (in relation to your chronic disease) you would like to see continue after the pandemic.