ABSTRACT

The transition from driving to driving cessation in older adulthood is considered a major life transition where resulting disruptions can impact sense of self. Such transitions at this life stage offer both a challenge and opportunity to consider the relationship between disruption, adaptation (or not) of occupational patterns, and perceptions of life roles. The current study examines this process of adaptation where the focus is on exploring how disruption, loss, and identity over time are negotiated at this life stage. Semi-structured interviews with each participant explored this process. Based on these interviews and corresponding narrative analysis, the trajectories of each of the five older adults (4 male, 1 female; aged 73-90) were categorized and mapped. The analysis indicated the narrative slopes of three participants were ‘progressive’ (more ups than downs), one participant was ‘stable’ (landing where one started), and the remaining participant was ‘regressive’ (more downs than ups). Results from this study suggest the process of negotiating the transition from driver to non-driver was non-linear, meaning the ensuing adaptations to everyday life involved a major reorganization of occupations and routines. Social support and finding alternative ways of doing were key to negotiating this transition. Challenges experienced during the transition and/or, a failure to adapt, suggests an ongoing and growing disconnect in life roles. Further study of the impact of such disconnection and the ramifications on not only the person but also their social network is warranted.

老年期从开车到停驾的转变被认为是重大的人生转变,由此产生的干扰会影响自我意识。该人生阶段的这种转变既提供了挑战,也提供了机会来考虑干扰、生活活动模式的适应(或不适应)和对生活角色的看法之间的关系。该研究考察了这个适应过程,重点探索在这个人生阶段如何处理无时不在的干扰、损失和身份。通过对每个参与者的半结构化访谈探讨了这个过程。根据这些访谈和相应的叙述分析,对五位老年人(4 男 1 女;年龄 73-90 岁)的轨迹分别进行分类和绘制。分析表明三个参与者的叙事倾斜是“进步的”(多起少落),有一个参与者是“稳定的”(回到起点),剩下的一个参与者是“倒退的”(落多于起)。这项研究的结果表明,从司机到非司机的适应过程是非线性的,这意味着随后对日常生活的适应涉及生活活动和常规的重大重组。社会帮助和寻找替代方式是适应这一转变的关键。过渡期间遇到的挑战和/或未能适应,表明生活角色的脱节正在持续且日益增长。有必要进一步研究这种脱节及其后果不仅对个人而且对他们的社交网络的影响。

Se considera que la transición entre la conducción [de automóviles] y el cese de la misma en adultos mayores es una transformación vital importante. Los trastornos resultantes de esta pueden afectar el sentido de sí mismo. Tales transiciones en esta etapa de la vida suponen, al mismo tiempo, un reto y una oportunidad para considerar la relación entre la interrupción, la adaptación (o no) de los patrones ocupacionales y las percepciones en torno a los roles vitales. El presente estudio examina este proceso de adaptación, centrándose en analizar cómo se sortean los trastornos, las pérdidas y la identidad a lo largo del tiempo durante esta etapa de la vida. Se indagó en este proceso mediante entrevistas semiestructuradas realizadas con cada participante. Sobre la base de las mismas y el correspondiente análisis narrativo, se categorizaron y mapearon las trayectorias de cinco adultos mayores (4 hombres, 1 mujer; de 73 a 90 años). El análisis indicó que las trayectorias narrativas de tres participantes eran “progresivas” (más subidas que bajadas), un participante era “estable” (aterrizaba en el punto de partida), y el restante era “regresivo” (más bajadas que subidas). Los resultados del estudio dan cuenta de que el proceso de sortear la transición de conductor a no conductor no fue lineal. Ello significa que las consiguientes adaptaciones realizadas en la vida cotidiana implicaron una importante reorganización de las ocupaciones y las rutinas. Para encarar dicha transición, fueron fundamentales el apoyo social y la búsqueda de formas alternativas de hacer las cosas. Los desafíos a enfrentar durante la transición y/o el fracaso en la adaptación apuntan a una desconexión continua y creciente en los roles de la vida. A la luz de lo anterior se justifica un mayor estudio del impacto que supone dicha desconexión, así como de sus ramificaciones, no sólo en la persona sino también en su red social.

RÉSUMÉ

Pour les personnes âgées, le passage de la conduite à l'arrêt de la conduite est considéré comme une transition majeure dont les perturbations qui en résultent peuvent avoir un impact sur l'identité. De telles transitions à cette étape de la vie offrent à la fois un défi et une opportunité d'examiner la relation entre la perturbation, l'adaptation (ou non) des patterns occupationnels et les perceptions des rôles sociaux. La présente étude examine ce processus d'adaptation en se concentrant sur l'exploration de la manière dont la perturbation, la perte et l'identité au fil du temps sont négociées à cette étape de la vie. Des entretiens semi-structurés avec cinq personnes (4 hommes, 1 femme de 73 à 90 ans) ont permis d'explorer ce processus. Sur la base de ces entretiens et de leur analyse narrative respective, les trajectoires de chacune des personnes ont été catégorisées et cartographiées. L'analyse a indiqué que les pentes narratives de trois d'entre elles étaient “progressives” (plus de hauts que de bas), qu'une personne était “stable” (finissant là où il a commencé) et que la dernière était “régressive” (plus de bas que de hauts). Les résultats de cette étude suggèrent que le processus de négociation de la transition d'une personne conductrice à non-conductrice n'est pas linéaire, ce qui signifie que les adaptations à la vie quotidienne qui ont suivies ont impliqué une réorganisation majeure des occupations et des routines. Le soutien social et la recherche d'alternatives ont été essentiels pour négocier cette transition. Les difficultés rencontrées pendant la transition et/ou l'échec de l'adaptation suggèrent une déconnexion continue et croissante avec les rôles sociaux. Une étude plus approfondie de l'impact d'une telle déconnexion et de ses ramifications non seulement sur la personne mais aussi sur son réseau social est judicieuse.

As individuals move through their lifespan, they can experience major events or life transitions that significantly impact their everyday habits and routines. Older adulthood, in particular, is recognized as a life stage replete with events that can result in major changes; some of which add a layer of stress, particularly for those who may already be struggling with changing life circumstances (Gironda & Lubben, Citation2003; Victor et al., Citation2000). The combination of changes in both personal and contextual factors, such as not having adequate social support, can make coping with a major transition even more challenging in later life (Oris et al., Citation2017). In other words, transitional events may become stressful if they destabilize daily life, which can potentially trigger a process of major adjustment (Prigerson et al., Citation1994; Rubio et al., Citation2016).

In older adulthood, individuals often contend with multiple life transitions, such as retirement from paid employment, loss of a spouse, and/or moving their place of residence. These transitions, whether voluntary or otherwise, impact individuals differently. While Lane and Reed (Citation2015) noted some of the adverse consequences that might ensue following such transitions, including mental health issues, social isolation, depression, addiction, as well as higher rates of morbidity and mortality, even suicide, findings from other studies have suggested otherwise. For example, in a study of the transition from work to retirement, many participants described how they were able to spend more time on the leisure occupations they valued (Jonsson et al., Citation2000). In fact, such research suggests daily life may undergo significant re-organization, which can impact how such a transition is perceived by the individual in question.

In a review of research focused on life transitions in occupational science and the broader literature, Crider and colleagues (Citation2015) highlighted how certain transitions at this life stage, such as retirement (Jonsson et al., Citation2001) and driving cessation (Liddle et al., Citation2004; Marken & Howard, Citation2014; Vrkljan & Miller-Polgar, Citation2001), can have major repercussions on everyday habits, routines, and identity. Hence, to set the stage for the current study, it is important to first reflect on the transition from driving to driving cessation, with a particular focus on the construct of occupational disruption and the corresponding complexities involved in the re-organization of occupational patterns during this transition in later life.

In many Western societies, driving is a common occupation (Chihuri et al., Citation2016; Dickerson et al., Citation2011). In older adulthood, being able to drive, together with car ownership, has been linked to higher levels of out-of-home participation in occupation (Chihuri et al., Citation2016; Gaugler, Citation2016; Liddle & McKenna, Citation2003). While having a license is often equated with personal freedom, no longer being able to drive can result in feelings of loss of control and choice over one’s daily routine. In their case study exploring the reflections of an older driver experiencing this loss, Vrkljan and Polgar (Citation2007) conceptualized driving cessation as an occupational disruption, a concept earlier defined as a temporary or transient state that can change the way in which an occupation or occupations are performed (Whiteford, Citation2000). In their recent scoping review of evidence specific to disruption using an occupational science lens, Nizzero and colleagues (Citation2017) proposed a more comprehensive definition where interconnectedness between changes in routine and identity were emphasized:

A temporary state, characterized by a significant disruption of identity associated with changes in the quantity or/and quality of one’s occupations subsequent to a significant life event, transition, or illness or injury. It has the potential to affect multiple areas of functioning, including social and emotional functioning. (p. 125)

With this disruption and loss comes the need to re-organize or adapt occupational patterns. Older individuals who may not be able to engage in desired occupations can experience changes in their identity (Nizzero et al., Citation2017; Vrkljan & Polgar, Citation2007). The definition of occupational disruption, as outlined by Nizzero and colleagues (Citation2017), recognizes the potential implications on both emotional and social well-being, yet the “actual nature of the disruption” (p. 123) and corresponding adaptations remain unclear. As such, exploring how individuals re-organize and re-engage in occupational patterns of living, or not, following a major disruption or loss of roles is important if the ensuing impact on occupational identity is to be understood.

Where the occupation that has been ‘lost’ (i.e., driving) played a prominent role in everyday life, the ensuing loss of this and other occupations can be devastating (Townsend & Polatajko, Citation2007). However, there are also examples of individuals navigating difficult life circumstances to re-engage in meaningful occupations. In her study of lived experiences following a major brain injury, Klinger (Citation2005) found participants principally aimed to re-define and accept their self-identity (their being), which was related to their level of effort to adapt their occupations and routines (the doing). Retirement from paid employment is another example of individuals needing to adapt their lifestyle due to occupational loss. Jonsson et al. (Citation2000, Citation2001) described how some retirees readily adapted to a new rhythm of life whereas others had more difficulty with this transition. In fact, their findings highlighted how the meaning ascribed to paid employment could affect how retirees adapted to everyday life post-retirement. Hence, major life transitions, such as driving cessation, offer both a challenge and an opportunity to consider why some older adults seemingly adjust to occupational loss whereas others can experience more difficulty.

Building on the work of Jonsson et al. (Citation2000) with respect to analyzing the transition of retirement and ensuing lifestyle adaptations, the current study used a similar approach to examine the process of driving cessation in later life. The focus was on understanding how individuals adapt their occupational patterns following a major disruption. The present study aimed to draw connections between driving cessation, disruption, loss, and identity over time.

Method

Design of the study

This study received ethics approval from the Cantonal Commission of Ethics for Research on Humans (CER-VD) (protocol number 2016-00911). Our research design was framed using a narrative inquiry. In the current study, loss of driving licensure was the key point of occupational disruption. Thus, the focus of the analysis was on the meaning attributed to driving and other occupational roles by the participants at the time of and after the transition, particularly if and how these roles were affected.

Narratives are recognized as being dynamic in nature, meaning they are constantly changing and, as such, how they are constructed can depend on the point at which a person is asked to share their perspective on a particular event or set of circumstances. For each narrative, Gergen and Gergen’s (Citation1988) approach to categorizing a narrative trajectory as progressive, regressive, or stable was used. A progressive narrative refers to when an individual’s respective life circumstances are described and/or interpreted as globally positive, whereas a regressive narrative refers to an apparent deterioration due to the event in question, as reflected in a perceived decline in their circumstances. Finally, a stable narrative suggests circumstances might at first ‘progress’ or ‘regress’, or both, but eventually resolve to be not much different than prior to the event in question.

While only having three options to describe the slopes may seem a simplification, given the potential complexities involved, the strength is that it characterizes the narrative as a whole. Hence, this approach entails examining each narrative and plotting a ‘visual slope’ that reflects the time period of the events in question (Jonsson et al., Citation2000). The approach used by Gergen and Gergen (Citation1988) has proven particularly helpful when exploring complex phenomena like retirement, where participants often simply describe their lived experiences as ‘positive’ or ‘negative’, when, in fact, there are more subtle or nuanced elements that characterize their occupational transition. Jonsson and colleagues (Citation2000, Citation2001) illustrated the usefulness of this approach to illustrate how the narrative slopes of participants changed over time. The current study used a similar approach to Jonsson et al. but aimed to delve deeper into the fluctuations that occurred in the post-transition period from driver to non-driver.

Context, sampling, and recruitment

The study was conducted in western Switzerland. At the time of data collection (2016), there were 369,040 individuals aged 65 years and older in this region representing 16.9% of the total population (Swiss Federal Statistical Office, (OFS), Citation2020). Switzerland has one of the most highly integrated networks of public transport in Europe (Swiss Federal Office of Spatial Development (ARE), Citation2017), hence it was expected that older adults recruited to participate in the study would be aware of the different modes of transport in their region. Nonetheless, private vehicles are the predominant mode of personal travel, with more than 80% using this mode. Considering these points, purposive sampling was used to recruit individuals who met the following inclusion criteria: stopped driving for at least 1 year, aged 72 and older, not under guardianship, and live in the community.

At the time of the study,1 Swiss drivers aged 70 years and older were required to undergo a fitness-to-drive assessment every 2 years. Hence, the cut-off age of 72 was used to ensure each participant had completed at least one of these evaluations. Potential participants were contacted using snowball sampling, as the first author asked health professional colleagues to identify prospective participants. The study protocol was explained by phone to each participant. If they were agreeable to being in the study, a one-to-one meeting was arranged at a location of their choice (e.g., coffee shop, place of residence). At the in-person meeting, their written consent to participate in the study was obtained.

Data collection

A single, semi-structured interview was conducted with each participant by the first author. The interviews aimed to co-create the meaning participants attributed to the experiences surrounding the event of losing their driving license (DiCicco-Bloom & Crabtree, Citation2006; Polkinghorne, Citation2005). For example, open-ended questions were asked to understand the circumstances that led the individual to stop driving. The meaning of driving was also addressed with questions, such as “How important was it for you to be able to drive your own car?”, and the impact of this transition on their daily routines over time (e.g., “How do you feel this transition affected your daily activities when you first stopped driving? How has the fact that you stopped driving affected your current level of activity?). The circumstances leading up to driving cessation, the meaning of driving as an occupation preceding their loss of licensure, and the impact of losing their license on their daily occupational structure were discussed. As these experiences were shared, the interviewer asked follow-up questions to further explore the phenomenon, which is common during this type of interview (DiCicco-Bloom & Crabtree, Citation2006). Interviews lasted approximatively 1 hour and took place at each participant’s home. All interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

Data analysis was supported by MAXQDA 12 software. Within each narrative, the lived experience at the time of loss of licensure was examined with a particular focus on the disruptions and corresponding changes in occupational routines. From this examination, a narrative summary was written and a slope plotted for each participant (Jonsson et al., Citation1997; Levin et al., Citation2007). The first step in determining the slope was to review the respective experiences of the participants in chronological order. For example, occupational routines prior to and following loss of licensure were tracked. For the next step, key elements that influenced the experience were analyzed, such as presence of family support and other adaptations made by the participant to re-engage in certain occupations. The first author then compared participant narratives, from which common and unique elements were identified.

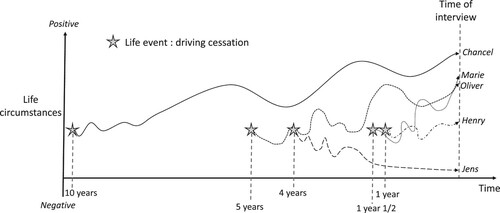

Of particular interest were the adaptations by which participants resumed various occupations, which informed the overall direction of the narrative slope. Using the framework of Gergen and Gergen (Citation1988), each participant’s slope was then categorized by the first author as progressive, regressive, or stable, alongside supporting elements (e.g., adaptations of resumed occupations). To ensure the slope reflected the participants’ experience, the first author then cross-referenced these elements in relation to the respective timeline of shared events during the interview. Finally, the first author provided an overview of this process to each of the authors, who provided comments. Following these conversations, each participant’s transition was then translated into a visual graphic, as per Levin et al. (Citation2007). In this graphic, the y-axis represents life circumstances and how they are experienced over time, where critical elements emerging from the narrative are categorized as either progressive (i.e., upward slope) or regressive (i.e., downward slope). When using this analytic technique, it is important to emphasize that any departure from participants’ respective timeline was identified as a key or ‘critical’ event (Gergen & Gergen, Citation1988).

After all the interviews and corresponding written narrative summaries were completed by the first author, each participant reviewed their respective summary and confirmed face-to-face that their experience was accurately captured in the summary. Interviews, transcriptions, and summaries were in French. For publication purposes, participant quotes to illustrate the findings were then selected and translated from French to English. The translation process was completed in collaboration with a native English speaker, a member of the authorship team. Each quote was first translated into English by the first author. A native English-speaking author then checked the meaning and made corrections as necessary to ensure proper grammar. Quotes were then translated back into French so that the first author (French-speaking) could verify the meaning remained evident from the initial translation. Some terminology within each narrative had to be reframed to ensure the meaning of the phenomenon was retained during this translation. Pseudonyms have been used to protect the confidentiality of the participants.

Findings

Five individuals aged 70 and older participated in the study. summarizes their respective demographics. All lived in geographic areas where public transport was available. Using the process suggested by Levin et al. (Citation2007), each participant’s narrative was translated to a slope that reflected their individual trajectories (see ). This slope illustrates the individualized impact this loss had on each participant, where the fluctuations reflect key elements as described in the respective narrative, including corresponding adaptations to their respective occupational patterns. As illustrated in , the transition to driving cessation is not a linear process, with a clear end per se, rather the loss of licensure can have ripple effect from which some participants’ are able to adapt and recover certain occupational pursuits whereas others found their lives forever changed.

Figure 1. Participants’ driving cessation narratives following the effective loss of licensure showing fluctuations of subjectively experienced life circumstances over time. Each line reflects a person’s trajectory. The point of departure corresponds to the time between driving cessation and the time of the interview. Its location on the vertical axis is an arbitrary choice with a view to standardization.

Table 1. Participant Demographics

Occupation disrupted: Reconciling the impact of loss of driving licensure in everyday life

Across all participants, driving cessation was described as a highly emotional, troubling, and unpleasant event. Loss of licensure was seen as one of the most challenging times of their lives regardless of the circumstances by which each experienced this loss. For all participants, driving had been embedded within their daily life and routine. This occupation was equated with freedom, generated pleasure, and was identified as a transactional point of mobility that enabled access to ‘real life’ and corresponding occupational roles. For instance, Jens stated: “Driving was important to me. Because it gave me a freedom that I had never had before.” Another participant, Henry shared: “I was free to decide by myself what I wanted to do. It’s what it means to me, freedom”; while Oliver explained: “I loved the feeling of freedom with my car, you know. It may be … strange, to be attached to a car”.

For some participants, like Jens, driving was associated with feelings of pleasure and enjoyment: “Me, I loved driving. When I got my license, I bought a car. It was a great discovery! I liked it right away because it gave me freedom.” Oliver’s emotions were similar to Jens, who described how he felt when behind-the-wheel: “Some people say it’s weird that you have to drive a car to feel good”. Conversely, Marie and Chancel, described having a license as more of a convenience than pleasure: “Yes, I liked driving, but I never made it a point to drive” (Marie); “It was simpler by car. I liked taking my car. It was more … simple, yeah. I enjoyed it, on weekends, holidays” (Chancel). While the participants described the importance of driving in their everyday life, there were subtle differences in their respective descriptions of how they viewed this occupation and the meaning ascribed to being behind-the-wheel, which become more apparent upon examining how they navigated their life roles and everyday occupations following their loss of licensure.

Narrative slopes during the time of driving cessation: Occupational loss and adaptation

Analysis of the narratives suggested different slopes for each participant, which reflected their lived experiences with navigating this transition, as graphically illustrated in .

Progressive narratives

Three participants were categorized as having progressive narratives. Based on the analysis of their subjective reflections, their occupational lives seemed to improve in the time following initial adaptations to their loss of their driver’s license. For these participants, the process of giving up their license was described as their “choice”, albeit for different reasons. For example, Chancel reported he “chose” to stop driving following a motor vehicle collision (MVC). He recalled driving with his wife and falling asleep behind the wheel. They were both shocked, and so, Chancel asked the mechanic to keep the damaged car. On the other hand, Marie had suffered a fracture to her right ankle in an MVC. While the crash had not been her fault, she had trouble managing her pain and also moving her foot to “brake and accelerate”. On her physician’s advice, she chose to stop driving temporarily but the pain continued and so she discussed giving up her license with her family: “I had a family reunion with my son and my niece who’s around a lot and they decided it was best if I just quit.” Another participant, Oliver, also decided to stop driving because of changes in his vision. Although his ophthalmologic exam confirmed his visual deficits, he still saw the decision to stop driving, as his choice. “My vision was declining, it was dangerous … And my safety was important to me … Maybe … that’s why I thought it was wise to stop.” While some of these participants indicated their decision to stop driving as a choice, they all described the time after they lost their license as a period of high stress, where the magnitude of this loss on their occupational patterns emerged. Marie stated:

Later, I came down to earth. To stop driving meant that I had to move around differently, and I had not planned anything. So, I was quite distressed! I wondered how I could manage from now on, without being a burden on my family. That’s exactly these questions you ask yourself … When you are used to doing things in a certain way that you cannot do anymore.

For Oliver, the ability to readily access the places he wanted was lost: “it was so difficult to imagine that I could not do as I wanted” and was worried that his life was forever changed: “what I precisely liked to do, I thought that I wouldn’t have the possibility of doing again”. However, it is important to note the negative emotions attributed to this loss by these participants only lasted a few weeks. When asked how they managed, they emphasized the critical role of their family. For example, Chancel shared how his wife, in particular, helped process the emotional loss: “my wife helped me a lot to decide. It was very helpful for me.” Social support was critical when considering mobility alternatives to get around their community beyond the personal automobile, Oliver explained: “it’s true that they helped me realize I could manage differently.” He recalled his daughter asking: “but why don’t you take the bus to come to visit me?” By taking the bus and re-engaging with his daughter, he realized: “I was not really as stuck as I thought.”

Both Marie and Chancel indicated they were able to continue engaging in occupations despite no longer being able to drive. Marie, who enjoyed many outdoor pursuits for which she thought driving was necessary, realized that taxis enabled her to get where she need to go: “Now, taxis are good. Even if I don’t move around as much as before, I do it when I want to, and I can see my family as before.” Marie then proceeded to list all the occupations and roles she was presently doing, such as going to the lake to join her grandchildren, visiting her daughter, or go shopping. However, similar to Marie, Oliver and Chancel still found their out-of-home activity levels were lower after losing their license, but they adapted. For example, family and friends came to their home, as Oliver stated: “We meet them less often than before, but it’s not a problem. What is important is to see them.” They noticed more at-home occupations, such as watching TV and playing cards with their spouse or family. When reflecting on her life without a driver’s license, Marie stated: “car or no car, the important thing for me is to continue to do things I like to do.” Chancel shared that he discovered occupations he had never done before, such as writing poetry, exclaiming “I have been published once.” These participants saw themselves looking forward to their life, not back to their past pursuits. They seemed to accept driving cessation as a natural step in the aging process. They adopted new daily patterns and, in some cases, roles. Chancel summarized his life without his automobile:

Now I am happy, even without my car. I get a lot of pleasure from what I do. I see my family as often as I want; my wife is staying with me … I play on my computer, I write poems … Well, it’s not the freedom I had before, but it’s just different. I preserve my health. I don’t take any risks. Isn’t it good? I’m at peace with myself.

Stable narrative

The experience of one participant, Henry, was characterized as having a stable narrative slope. At the time of his interview, this participant considered his life circumstances as being the same as before he ceased driving. For Henry, the decision to stop driving was not his choice. His license had already been restricted for a few years due to a degenerative visual impairment where he was not allowed to drive “at night and on the highway.” Following one of his visual examinations, his doctor informed him that it was too dangerous for him to drive and refused to extend his license. Although Henry had restrictions in place and knew his vision would deteriorate to the point he could no longer drive, he never anticipated a complete cessation of this occupation. He described the devastation he felt at hearing the doctor’s decision: “It’s like they’re telling you that you have a cancer. They throw it in your face. It’s a similar shock and we can only accept it.”

Henry described the months following the loss of his license as an extremely difficult time, especially “emotionally.” No longer being able to drive was yet another loss in a series of losses in life roles, as he had recently retired, then his wife passed away. Driving, he said, had helped him cope with the loss of his spouse. He would meet his friend at the pub, go to his children’s home, and out for the groceries. All these occupations and roles (i.e., friend, grandfather) were critical social connections for him. He described how he used to drive for the pleasure of being behind the wheel: “I’ve always loved it [driving]. I’ve owned about 10 cars in my life.” Dealing with this loss manifested as heightened anxiety about his health and his existence: “Of course, I was wondering … How could I carry on as before? I was shocked. I still had problems with my eyes, with my legs, I couldn’t move around, I couldn’t go to the shops, I couldn’t do anything”. He was angry at the doctor: “They were giving me a hard time … It was terrible for me.”

Henry identified that his family, especially his son, was a great support, frequently visiting to bring various items and groceries. He described this time in his life as very dark, given that he was staying at home, didn’t see friends, or go the pub: “I was doing nearly nothing. For me it was like the end because I thought that it wasn’t worth living like that, being stuck like that.” Henry said he refuses to use public transport and that taxis are too expensive. He didn’t want to rely on anyone, which he saw as core to his being: “Me, I don’t like being at the mercy of someone, you know? I don’t like asking people to drive me around. No, I don't like it.”

A few months after Henry stopped driving, his son asked if he would like to try an electric scooter. Henry described the scooter as a major turning point in his emotional well-being: “It was after I bought the scooter, … it's completely changed my situation”. Although he had to be extremely cautious operating the scooter due to his visual impairment, he had enough vision to navigate his nearby community using it. He was able to go out again and he described his world as much brighter: “There are places where I don’t go anymore. But it’s no more a problem, because … Truly, the most important thing is that I can go places.” While “driving my scooter will never be the same as driving my car”, he was grateful for his current level of mobility: “Never … But I am truly happy to be free to move around as before.”

Regressive narrative

The narrative of one participant, Jens, was categorized as being ‘regressive.’ At the time of his interview, he described how his personal circumstances had deteriorated since he stopped driving. Jens indicated he was forced to stop driving due to a neurogenerative disease, which had progressed to the point that he could no longer operate his vehicle: “I was shaking and my movements … Well, I didn’t control them. And it got worse and worse, and then I was afraid that I couldn’t control my car.” At the time of his medical exam, he was told not to drive. Although Jens understood the seriousness of his health condition, he had hoped there might be a treatment or cure for his disease. He never anticipated this loss. Hence, he faced an emotional paradox; wanting to drive but knowing it was dangerous. Jens shared his ongoing anger about losing his license:

You have to understand, I was so upset because I couldn’t figure out how I was going to manage now. Well, at least, it was satisfying that I had done something that was good for others. Because I probably would have done something stupid sooner or later. But for everything else, it was … hard.

Having once had a vibrant social network, Jens reported that it was inconceivable for him to see his friends after he lost his license. He saw driving cessation as a major marker of decline. Jens rarely accepted invitations from others to drive him: “Don’t want to feel that I’m a burden on them.” Over time, Jens began to see his friends, but not accept rides. Instead, his friends came to his home. He described seeing his friends as rare moments of pleasure. For Jens, driving cessation was a marker of his ongoing physical decline: “I don’t really feel like much anymore. I don’t really have pleasures anymore … And with this damned disease, … I almost feel like dying quickly, you see.”

Discussion

As highlighted through the analysis, driving cessation exemplifies how the transitional periods in older adulthood can involve major losses not only in terms of the occupation itself, but also the reverberating disruption such a loss can have on an individual’s occupational patterns and corresponding roles at this life stage. Based on our analysis, some were able to adapt and cope with changes in their occupational routines, or even create new roles. Conversely, for others in the study the magnitude of the loss of driving and corresponding ramifications on occupational patterns and life roles seemed to trigger what Vrkljan and Polgar (Citation2007) coined an “occupational identity crisis” (p. 35). While they did not elaborate on the elements that may trigger such a crisis, their focus was on understanding the link between occupational identity and participation during the transition from driving to driving cessation, as experienced by an older married couple, one of whom had stopped driving. Findings from the current analysis also focus on this transition but suggest that the process of adaptation to occupational patterns and routines is critical following loss of driving licensure. Without sufficient adaptation, there can be an ongoing and growing disconnect in life roles and, in turn, identity.

Both Henry and Jens described the enormity of the loss of driving on daily life, which was in addition to other losses recently experienced, such as loss of work, loss of their spouse, as well as health issues. While Henry had been able to find alternative ways of getting around his community and resumed certain roles, Jens continued to struggle with navigating the changes that ensued following his loss of licensure. Hence, some of the participants in the current study were able to reorganize their occupational patterns thereby preventing such a crisis, but others found themselves questioning their occupational futures. Using narrative inquiry, this study identified the link between occupational disruption, loss, and adaptation, as reflected in the individuality of their respective slopes. Each slope illustrates the complexity involved with navigating this transition where adaptations to pre-existing routines and habits aim to minimize further occupational loss.

Navigating driving cessation in older adulthood: Preventing further occupational loss

For all participants, loss of licensure resulted in a dual ‘loss’, meaning participants had to cope with their lost capacity to drive as well as the resulting impact on other occupational pursuits. Our analysis corroborates that of Liddle and colleagues (Citation2008), who described driving cessation as a three-phase process where the resulting impact of loss of licensure was outlined as the final stage. They similarly noted the importance of adaptation and adjustment in finding ways to participate as well as reorganizing patterns and occupations. Through the use of narrative slopes in the current paper, we outline an alternative way to reflect the process of adaptation, as experienced by the participants in our study.

Liddle et al. (Citation2008) also suggested older adults may adapt their narrative to feel more in control of their decision to stop driving. Our study found that some participants had accepted the loss of licensure whereas others continued to struggle. However, it is important to consider that some of our participants were interviewed quite a long time after having stopped driving. For example, Chancel, who was interviewed 10 years after losing his license, may have had more time to come to terms with this loss. However, Henry or Jens may not have yet reconciled their experiences. Interestingly, Marie had lost her license around the same time as Henry and Jens, yet her slope reflected her progressive outlook. Due to study design, it is difficult to discern if differences between participants were related to the length of time from the event in question. Nonetheless, the analysis suggested that adaptation of occupational routines during this time of transition was critical to participants navigating the ensuing changes in occupations and roles.

Occupational adaptation in times of transition: Driver to non-driver

Participants in the current study adapted their occupational routines post-cessation, some more successfully than others. Factors identified as helping and/or hindering their transition from driver to non-driver were congruent with those found in previous studies, namely having social support (e.g., Choi et al., Citation2012; Mezuk & Rebok, Citation2008), re-organizing their occupational patterns (e.g., Jonsson et al., Citation2000; Vrkljan & Polgar, Citation2007), as well as finding alternative ways of doing (e.g., Dickerson et al., Citation2019; Liddle et al., Citation2008).

Role of social support

Results confirmed the critical role of family and friends on helping individuals come to terms with no longer having a license (Choi et al., Citation2012). Within each narrative, participants shared how such supports helped them navigate this loss, including the decision to give up their license, which are congruent with the phases of driving cessation described by Liddle et al. (Citation2008). Each narrative demonstrated differing roles of social support, where those with an upward trajectory identified family and friends being more involved in their decision to stop driving. Having such support after cessation was particularly valued. Given the struggle with this transition for some, a participant emphasized the emotions associated with re-connecting with his social network, which he surmised as one of his “rare moments of pleasure.”

Reorganization of occupational patterns and “ways of doing”

All the participants had to adapt their routines following their loss of licensure. The back and forth that can occur during times of transition, where individuals reshape their everyday lives between old and new occupations, was also raised by Jonsson et al. (Citation2000) in their study of the transition of retirement. They found that if engagement in an occupation is maintained during a transition such as retirement, the meaning of the occupation may evolve. In this way, the newly adopted occupational pattern can give a whole new meaning to life (Jonsson et al., Citation2000). As demonstrated in the current study, Chancel, Marie, and Oliver, whose narratives reflected efforts to adapt routines in order to preserve engagement in key occupations, were able to find a new ‘rhythm’ in their daily lives. In fact, Chancel discovered a passion for poetry; one he might not have found if not for changing his ways of doing. Such findings corroborate the work of Vrkljan and Polgar (Citation2007), who described the relationship between maintaining patterns of occupational participation and identity, but challenge Klinger’s (Citation2005) assertion where participants in her study who had experienced a brain injury “had to learn a new way of ‘being’ in order to move onto a new way of ‘doing’” (p. 14). In other words, they had to ‘accept’ who they were ‘now’ before occupational adaptations could ensure. Results from the current study highlight that adapting routines, roles, and patterns of living following a major occupational loss is an ongoing and dynamic process that begins, even if one continues to struggle emotionally with the loss in question. Hence, adapting the doing, where possible, in the face of disruption and due to the complexities involved, is not easy but critical.

Finding alternative ways of doing

Following their loss of licensure, participants in the current study described the challenge of finding transportation alternatives to their personal automobile. This finding is an example of what Liddle et al. (Citation2008) described as re-organizing patterns and occupations in the post-cessation phase of their model. However, some participants in the current study struggled to find and use alternatives to their car, with one participant spending most of his time at home after losing his license. Results suggest that finding alternate ways of doing goes beyond locating viable transport beyond driving, but also changing and adapting many other routines and roles to maintain engagement in later life (Dickerson et al., Citation2019; Liddle et al., Citation2008). Hence, it is important to consider the potential repercussions of failing to find alternative ways on not only the individual in question but also their social network. Interestingly, those who saw driving as a means, rather than an end, in terms of accessing other occupations, seemed to more readily adapt to their changing circumstances following cessation of driving.

Limitations

The results of this study are limited by the convenience sample recruited for this study. While the experiences of these participants are not representative of all individuals at this life stage, the opportunity to delve deeper into such experiences and closely examine each narrative was possible. For instance, the participants seemed to have the financial resources to navigate the transition. Without such resources there is potential for the experience of navigating this transition to be quite different. Additionally, the participants came from the same geographic region in Western Switzerland, which should be carefully considered given the differential impact and meaning of driving cessation in this cultural context. Switzerland is a small country, with a dense network of public transport, thus applying the findings to contexts without such a network must be done with caution. Further study using a gender lens on such transitions should also be considered. While the influence of gender was beyond the scope of the current study, there is recent evidence to suggest differential roles with respect to driving by gender, which, in turn, might affect self-regulation of driving as well as driving cessation in later life (Ang et al., Citation2020; Barrett et al., Citation2018).

Another limitation relates to the chosen methodology of using narratives slopes. Given the way these slopes are illustrated, the trajectories may appear static rather than dynamic. Hence, it is important to note that the point at which the interview was undertaken was not when the event occurred per se. As depicted in , the time from the respective loss of license (i.e., event) varied between participants, which may influence how they perceived this experience. Nonetheless, participants were asked the same set of questions upon which to reflect. Having participants with a similar timeframe from the event in question may reduce the potential for recall bias, with further exploration required.

Conclusion

Driving cessation is an example of a major transitional event in older adulthood where individuals can experience disruptions in their everyday routines. While capturing the meaning of occupation during times of disruption is critical, as evidenced in previous research (Nizzero et al., Citation2017), the current study provided both an opportunity and a challenge to examine how individuals navigated their loss of driving licensure and the resulting impact on their occupational patterns and roles. The individualized trajectories that emerged from each narrative reflect how individuals’ corresponding patterns of engagement can evolve over time. This study sets the stage for future research that considers tracking and comparing trajectories for other major life events, not only in older adulthood but along the life course. For this purpose, it may be important to interview people in a similar timeframe following such an event to more closely examine elements, including their social network, and how that might influence their transition with respect to adaption, adoption, and/or loss occupational patterns and roles.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The law changed in 2019. Fitness-to-drive assessments now begin at age 75 and are repeated every 2 years thereafter.

References

- Ang, B. H., Oxley, J. A., Chen, W. S., Yap, M. K. K., Song, K. P., & Lee, S. W. H. (2020). The influence of spouses and their driving roles in self-regulation: A qualitative exploration of driving reduction and cessation practices amongst married older adults. PLOS ONE, 15(5), e0232795. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232795

- Barrett, A. E., Gumber, C., & Douglas, R. (2018). Explaining gender differences in self-regulated driving: What roles do health limitations and driving alternatives play? Ageing & Society, 38(10), 2122–2145. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X17000538

- Chihuri, S., Mielenz, T. J., DiMaggio, C. J., Betz, M. E., DiGuiseppi, C., Jones, V. C., & Li, G. (2016). Driving cessation and health outcomes in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 64(2), 332–341. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13931

- Choi, M., Mezuk, B., & Rebok, G. W. (2012). Voluntary and involuntary driving cessation in later life. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 55(4), 367–376. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2011.642473

- Crider, C., Calder, C. R., Bunting, K. L., & Forwell, S. (2015). An integrative review of occupational science and theoretical literature exploring transition. Journal of Occupational Science, 22(3), 304–319. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2014.922913

- DiCicco-Bloom, B., & Crabtree, B. F. (2006). The qualitative research interview. Medical Education, 40(4), 314–321. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02418.x

- Dickerson, A. E., Molnar, L. J., Bédard, M., Eby, D. W., Berg-Weger, M., Choi, M., Grigg, J., Horowitz, A., Meuser, T., Myers, A., O’Connor, M., & Silverstein, N. M. (2019). Transportation and aging: An updated research agenda to advance safe mobility among older adults transitioning from driving to non-driving. The Gerontologist, 59(2), 215–221. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnx120

- Dickerson, A. E., Reistetter, T., Davis, E. S., & Monahan, M. (2011). Evaluating driving as a valued instrumental activity of daily living. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 65(1), 64–75. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2011.09052

- Gaugler, J. E. (2016). Driving and other important activities in older adulthood. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 35(6), 579–582. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464816647560

- Gergen, K. J., & Gergen, M. M. (1988). Narrative and the self as relationship. In L. Berkowitz (Éd.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 21, pp. 17–56). Academic Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60223-3

- Gironda, M., & Lubben, J. (2003). Loneliness/isolation, older adulthood. In T. P. Gullotta, M. Bloom, J. Kotch, C. Blakely, L. Bond, G. Adams, C. Browne, W. Klein, & J. Ramos (Eds.), Encyclopedia of primary prevention and health promotion (pp. 666–671). Springer. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-0195-4_98

- Holden, A., & Pusey, H. (2020). The impact of driving cessation for people with dementia: An integrative review. Dementia, 1471301220919862. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301220919862

- Jonsson, H., Borell, L., & Sadlo, G. (2000). Retirement: An occupational transition with consequences for temporality, balance and meaning of occupations. Journal of Occupational Science, 7(1), 29–37. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2000.9686462

- Jonsson, H., Josephsson, S., & Kielhofner, G. (2001). Narratives and experience in an occupational transition: A longitudinal study of the retirement process. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 55(4), 424–432. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.55.4.424

- Jonsson, H., Kielhofner, G., & Borell, L. (1997). Anticipating retirement: The formation of narratives concerning an occupational transition. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 51(1), 49–56. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.51.1.49

- Klinger, L. (2005). Occupational adaptation: Perspectives of people with traumatic brain injury. Journal of Occupational Science, 12(1), 9–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2005.9686543

- Lane, A. M., & Reed, M. B. (2015). Older adults: Understanding and facilitating transitions (2nd ed.). Kendall Hunt.

- Levin, M., Kielhofner, G., Braveman, B., & Fogg, L. (2007). Narrative slope as a predictor of work and other occupational participation. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 14(4), 258–264. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/11038120701327776

- Liddle, J., Carlson, G., & McKenna, K. (2004). Using a matrix in life transition research. Qualitative Health Research, 14(10), 1396–1417. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732304268793

- Liddle, J., Gustafsson, L., Mitchell, G., & Pachana, N. A. (2017). A difficult journey: Reflections on driving and driving cessation from a team of clinical researchers. The Gerontologist, 57(1), 82–88. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw079

- Liddle, J., & McKenna, K. (2003). Older drivers and driving cessation. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 66(3), 125–132. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/030802260306600307

- Liddle, J., Turpin, M., Carlson, G., & McKenna, K. (2008). The needs and experiences related to driving cessation for older people. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71(9), 379–388. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/030802260807100905

- Marken, D. M., & Howard, J. B. (2014). Grandparents raising grandchildren: The influence of a late-life transition on occupational engagement. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics, 32(4), 381–396. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/02703181.2014.965376

- Mezuk, B., & Rebok, G. W. (2008). Social integration and social support among older adults following driving cessation. Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 63(5), S298–S303. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/63.5.S298

- Nizzero, A., Cote, P., & Cramm, H. (2017). Occupational disruption: A scoping review. Journal of Occupational Science, 24(2), 114–127. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2017.1306791

- Oris, M., Gabriel, R., Ritschard, G., & Kliegel, M. (2017). Long lives and old age poverty: Social stratification and life-course institutionalization in Switzerland. Research in Human Development, 14(1), 68–87. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15427609.2016.1268890

- Pachana, N. A., Jetten, J., Gustafsson, L., & Liddle, J. (2017). To be or not to be (an older driver): Social identity theory and driving cessation in later life. Ageing and Society, 37(8), 1597–1608. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X16000507

- Polkinghorne, D. E. (2005). Language and meaning: Data collection in qualitative research. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 137–145. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.137

- Prigerson, H. G., Reynolds, C. F., Frank, E., Kupfer, D. J., George, C. J., & Houck, P. R. (1994). Stressful life events, social rhythms, and depressive symptoms among the elderly: An examination of hypothesized causal linkages. Psychiatry Research, 51(1), 33–49. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(94)90045-0

- Rubio, L., Dumitrache, C., Cordon-Pozo, E., & Rubio-Herrera, R. (2016). Coping: Impact of gender and stressful life events in middle and in old age. Clinical Gerontologist, 39(5), 468–488. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2015.1132290

- Swiss Federal Office for Spatial Development. (2017). Transport behaviour of the population 2015. https://www.are.admin.ch/are/fr/home/mobilite/bases-et-donnees/mrmt.html

- Swiss Federal Statistical Office. (2020). Data on the age of the permanent resident population by nationality category and sex, 1999-2019. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/en/home/statistics/population/effectif-change/age-marital-status-nationality.assetdetail.14367965.html

- Townsend, E. A., & Polatajko, H. J. (2007). Enabling occupation: Advancing an occupational therapy vision for health, well-being, and justice through occupation. CAOT Publications.

- Victor, C., Scambler, S., Bond, J., & Bowling, A. (2000). Being alone in later life: Loneliness, social isolation and living alone. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 10(4), 407–417. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959259800104101

- Vrkljan, B., & Miller-Polgar, J. (2001). Meaning of occupational engagement in life-threatening illness: A qualitative pilot project. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 68(4), 237–246. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/000841740106800407

- Vrkljan, B., & Polgar, J. M. (2007). Linking occupational participation and occupational identity: An exploratory study of the transition from driving to driving cessation in older adulthood. Journal of Occupational Science, 14(1), 30–39. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2007.9686581

- Whiteford, G. (2000). Occupational deprivation: Global challenge in the new millennium. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63(5), 200-204