ABSTRACT

The influence of arts on health has long been researched but often in general terms or related to a patient population. Specific practice within everyday life remains under investigated. In this paper I argue that embroidering is an occupation where limited knowledge exists about how engagement might influence health. This qualitative narrative inquiry-based study was situated in the United Kingdom and gathered discursive data over 6 months with five women who embroidered. The research question aimed to establish how embroidering influences meaningful change within the context of a person’s everyday life. Interpreted through narrative analysis, the findings suggest that embroidering can promote meaningful change through an intimate companionship of body, mind, and materials. This companionship is situated, reciprocal, develops over time, and is proposed as the means for health potential. Once established, this companionship provides resources that can be used to manage everyday life and thus promote health and well-being. Considered as active agents in the embroidering process, materials can incite a combination of mental and physical responses, which become meaningful experiences associated with embroidering. These experiences may explain the recent fervour of crafting in everyday western societies and supports research that shows that the arts are a crucial component of health and well-being. In line with global health initiatives, consideration of the therapeutic companionship of body, mind, and materials is needed to further explore the transformative potential of engagement in specific crafts as media for improving and sustaining health and well-being.

长期以来,人们一直在研究艺术对健康的影响,但通常是一般性或与患者群体相关的。日常生活中的具体实践仍在探索中。在这篇文章里,我认为刺绣是一种生活活动,而关于参与这一活动如何影响健康的认知有限。这项基于叙述性调查的定性研究是在英国进行的。在 6 个月内收集了五名刺绣女性的话语资料。该研究目的在于确定刺绣如何在一个人的日常生活中产生有意义的变化。通过叙事分析解释,研究结果表明,刺绣可以通过身体、思想和材料的亲密相伴来促进有意义的变化。这种相伴是定位的,互惠的,随着时间的推移而发展,并且,我们建议将它作为健康潜力的手段。这种相伴关系一旦建立,将提供可用于管理日常生活的资源,从而促进健康和福祉。所用材料被认为是刺绣过程中的活性剂,可以同时激发精神反应和身体反应,这些反应成为与刺绣相关的有意义的经历。这些经历可以解释为什么最近西方社会对手工艺表现热诚,并对表明艺术是健康和福祉的重要组成部分的研究提供支持。根据全球健康倡议,我们需要考虑身体、心灵和材料的治疗性相伴,以进一步探索参与特定工艺的变革潜力。这种参与可以是改善和维持健康和福祉的媒介。

RESUME

L'influence des arts sur la santé fait depuis longtemps l'objet de recherches, mais souvent en termes généraux ou en relation avec des patients. La pratique spécifique dans la vie quotidienne reste peu étudiée. Dans cet article, je soutiens que la broderie est une occupation pour laquelle il existe des connaissances limitées sur la façon dont l'engagement peut influencer la santé. Cette étude qualitative de type narratif s'est déroulée au Royaume-Uni et a permis de recueillir des données discursives pendant six mois auprès de cinq femmes qui brodaient. La question de recherche visait à établir comment la broderie influence un changement significatif dans le contexte de la vie quotidienne d'une personne. Interprétés avec une analyse narrative, les résultats suggèrent que la broderie peut promouvoir un changement significatif grâce à un compagnonnage intime entre le corps, l'esprit et les matériaux. Ce compagnonnage est situé, réciproque, se développe dans le temps, et est proposé comme le moyen d'un potentiel de santé. Une fois établi, ce compagnonnage fournit des ressources qui peuvent être utilisées pour gérer la vie quotidienne et ainsi promouvoir la santé et le bien-être. Considérés comme des agents actifs dans le processus de broderie, les matériaux peuvent susciter une combinaison de réponses mentales et physiques, qui deviennent des expériences signifiantes associées à la broderie. Ces expériences peuvent expliquer la récente ferveur de l'artisanat dans la vie quotidienne au sein des sociétés occidentales et viennent étayer les recherches qui montrent que les arts sont une composante essentielle de la santé et du bien-être. Dans la lignée des initiatives mondiales en matière de santé, il est nécessaire de prendre en considération le compagnonnage thérapeutique du corps, de l'esprit et des matériaux afin d'explorer davantage le potentiel transformateur de l'engagement dans des types d’artisanats spécifiques en tant que médias pour améliorer et maintenir la santé et le bien-être.

La influencia de las artes en la salud ha sido investigada durante mucho tiempo, pero a menudo en términos generales o relacionados con cierta población de pacientes. La práctica específica de las artes en la vida cotidiana sigue siendo poco investigada. En este trabajo sostengo que el bordado es una ocupación sobre la que existe conocimiento limitado respecto a cómo la participación en ella puede influir en la salud. Este estudio cualitativo basado en la indagación narrativa se realizó en el Reino Unido y durante seis meses recogió datos discursivos de cinco mujeres que bordaban. La pregunta de investigación pretendió establecer cómo el bordado influye en el cambio significativo dentro del contexto de la vida cotidiana de una persona. Interpretados empleando el análisis narrativo, los resultados indican que el bordado puede promover un cambio significativo gracias al íntimo compañerismo entre cuerpo, mente y materiales. Este compañerismo es situado, recíproco, se desarrolla a lo largo del tiempo y se propone como medio potencial para lograr la salud. Una vez establecido, proporciona recursos que pueden utilizarse para gestionar la vida cotidiana y promover la salud y el bienestar. Considerados como agentes activos en el proceso de bordado, los materiales pueden incitar una combinación de respuestas mentales y físicas, que se convierten en experiencias significativas asociadas al bordado. Tales experiencias pueden explicar el reciente fervor por la artesanía en la vida cotidiana de sociedades occidentales y respaldan los resultados de investigaciones que demuestran que las artes son un componente crucial de la salud y el bienestar. En consonancia con las iniciativas de salud global, es necesario considerar el acompañamiento terapéutico del cuerpo, la mente y los materiales para seguir explorando el potencial transformador de la participación en artesanías específicas como medios para mejorar y mantener la salud y el bienestar.

Embroidering has a long history within human culture, with meaningful and symbolic connotations (Hunter, Citation2019), and has enjoyed a recent resurgence in popular culture (Wood, Citation2020). Within healthcare, handicrafts played a major role in post war rehabilitation and embroidering became an unlikely but valued occupation for ex-servicemen (Hunter, Citation2019; Thornely, Citation1948). Embroidering was considered as rehabilitation to distract the mind from emotional issues and restore dexterity (James, Citation1940; McBrinn, Citation2017). Further historical evidence suggests that needlework, including embroidering, was utilised to provide emotional solace (McBrinn, Citation2017), promote recovery of mental health (MacDonald, Citation1938), increase concentration (Astley-Cooper, Citation1941), as a distraction from pain (Smith, Citation1945), and in recovery from tuberculosis (Cox, Citation1947). Early clinicians noticed, valued, and harnessed the potential of embroidering, with practical understanding of how it could influence both body and mind.

Despite suggestion that embroidering is a therapeutic occupation (Banks-Walker, Citation2019), little attention has been given to understanding its health promoting potential, perhaps due to a western cultural notion of embroidering as an amateurish, feminine construct (Jefferies, Citation2016; Parker, Citation2010). Instead, more recent literature has placed emphasis on individuals’ everyday participation in ‘crafts’ (Pöllänen, Citation2015; Pöllänen & Voutilainen, Citation2018), ‘textiles’ (Kenning, Citation2015a, Citation2015b), ‘knitting’ (Adey, Citation2018; Brooks et al., Citation2019), ‘sewing’ (Clarke, Citation2020), and ‘tapestry’ (Demecs & Miller, Citation2019). This re-focus on individual participation is necessary (Riley, Citation2011), however, the issue remains that labels such as textiles are not specific and the need for research focused on distinct occupations remains (Dickie et al., Citation2006). Essentially, more refined knowledge about the multiple dimensions of everyday participation in specific crafts could further justify their use within health prevention, promotion, management, and treatment. However, the complexity of art occupations presents issues in understanding how participation may promote health and the processes that make this happen. Understanding has also been inhibited by poor clarity of research methodology, under-defined terms such as creative or art activities, and the inclination to recruit people who participate in a group.

Embroidering was considered an untapped resource for health promotion and selected as a craft worthy of further investigation. Like art occupations, it is accessible, combines manifold components that are known to promote individuals’ physical and mental health, and it can impact health needs within everyday life (Fancourt & Finn, Citation2019). The aim was to understand how participation in embroidering might influence meaningful change within the context of a person’s everyday life, with emphasis on how such crafts may support and improve health. For the purpose of this study, embroidery is defined as a method of decorating an already existing structure with a needle and thread (Harris, Citation2011). As such, it differs from other textiles which involve processes of construction or reconstruction (Riley, Citation2011). This study, developed by the first author and reported in the first person, explores how embroidering can promote change within a person’s everyday life in order to better understand the mechanism of change and how this might influence health.

Methodology

My doctoral journey began in response to my professional need to better understand the therapeutic potential of engagement in craft occupations. The co-authors, my PhD supervisors, provided academic guidance and practical support for the duration of my studies. I believed that my professional problem required consideration of occupational engagement as a process of change and in particular how participation is situated, enacted, and evolves over time (Yerxa, Citation2000). Fancourt and Finn (Citation2019) referred to necessary understanding the mechanism of change. I framed this as a narrative problem because it related to the transitional and contingent nature of individual experience of embroidering within a shared historical, social, and cultural context. This ensured focus on situated and temporal elements, which distinguishes narrative from other types of research (Josephsson & Alsaker, Citation2015). Using a narrative lens enabled me to gain a new and dynamic appreciation of human experience by grasping the complex and unintended consequential results of human action into a unified whole (Ricoeur, Citation1984), rather than into separate themes (Polkinghorne, Citation1995). Continuity is considered fundamental from a narrative perspective, where experience has a history, is ever changing, and always going somewhere (Clandinin & Connelly, Citation2000). Narratives, in this case, are outlined as templates from which stories are constructed and depend on shared cultural and literary narrative resources (Frank, Citation2010). Ultimately, the research aimed to develop practical and transferable knowledge, to illuminate tacit processes of change underlying practice (Willis et al., Citation2007).

Recruitment and ethical approval

Ethical approval was provided by the University of Brighton Ethics and Governance Committee. Recruitment was challenging as embroiderers were seemingly covert and private about their craft. Eventually, I recruited five participants using purposive sampling from distribution of a flier to university contacts, and after visiting and sharing the purpose of the study with a local Embroiderers Guild. The five women who agreed to participate consented to sharing their current and historical stories of embroidering over a 6-month period. My main consideration was to ensure that my participants were not exploited in any way, that they wanted to remain engaged, felt that they could withdraw at any time, that they were happy for their stories to be published, and that I interpreted these in a reflective, sensitive, and authentic manner.

Design

The narrative task called for collection of storied data that provided detail of situation, intentional states, happenings, action, and events. Based on the narrative design, I focused on a small group of embroiderers over time to gain deep insight into everyday practice. details the participants and how stories were collected and created. Based on a recommendation by Kohler Riessman (Citation2008), I visited each participant multiple times where we co-generated storied accounts of their embroidering practice. Data were discursive, unstructured, and conservational, and involved mutual participation in embroidering. I recorded and transcribed our dialogue verbatim.

Table 1. Overview of participants

Method of analysis

Narrative analysis was employed to interpret data, focusing on both unique stories and shared historical and cultural patterns, configurations, and arrangements within a developing narrative construct. Considered to have meaning beyond the individual, it was important that personal stories were positioned into wider social, cultural, and physical narratives, thus connecting biography and society (Bruner, Citation1990). My analysis explored situation, intentional states, happenings, action, and events shared within the meetings with each embroiderer. Use of narrative shaping allowed me to construe a meaningful pattern or narrative construct from the disconnected ‘messy talk’ and short stories collected as data (Andrews et al., Citation2013).

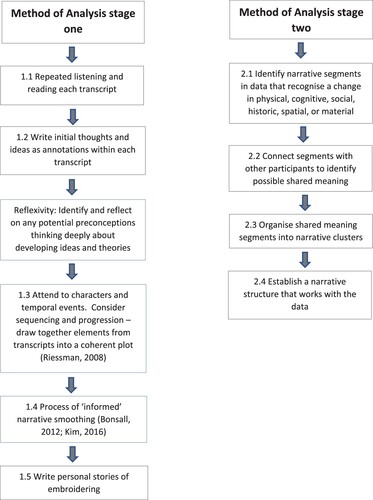

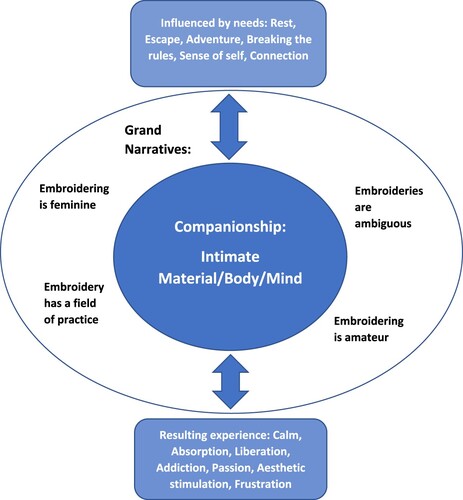

In essence, I blended Kohler Riessman’s (Citation2008) narrative thematic analysis with analysis of action (Andrews et al., Citation2013), which allowed insight into the meaning of embroidering as practiced within everyday life and how this structured past, present, and future action (Bonsall, Citation2012). Analysis involved two stages (). During the first, I created personal embroidering stories for each participant. This acknowledged the unique and situated experience of each person. The analysis enabled creation of a proposed narrative of how embroidering might influence health within the wider cultural context. For this purpose, in a second stage, I focused on changes that occurred through examination of situated and interactive elements within practice such as characters, actors, setting, time, tools, and materials. I concentrated on the sequencing and progression of conversations within interviews, their transformation, and resolution (Andrews et al., Citation2013). I identified narrative segments in the transcripts that recognised a change in physical, cognitive, social, historic, spatial, or material state that seemed to occur because of embroidering. In this way I was considering occupational life within an ever-changing past, present, and future context. Pertinent physical, cognitive, social, historic, spatial, or material changes were identified and separated as key narrative themes. This second stage of analysis was undertaken with data from each individual and then connected with the other participants to identify possible shared meaning in the form of a narrative construct (). I considered this construct as an inter-related and transitional process indicative of embroidering within everyday life, further interpreted to show how engagement might influence health.

Rigor

The findings show a narrative interpretation of the changes that occur as a result of embroidering. It is acknowledged that this involved reflexive processes and thus the findings may be transferable but not generalisable. I have used shared stories to demonstrate credibility and confirmability. The narrative construct () is an interpretation of how the stories interconnect to form a theory about how embroidering may influence health within everyday life. This construct was written with detailed use of a reflexive diary where I documented thoughts and feelings after each meeting, the possible meaning of embroidering, how I felt embroidering was situated in everyday life, and the connections between the stories within the context of the wider research question. During data analysis, I kept a detailed audit trail so that all of the stories could be traced back to the original transcript.

Findings

The findings of the second stage of analysis are discussed, beginning with embroidering as a narrative construct followed by the key finding of embroidering as companionship.

Embroidering as a narrative construct

The findings were complex but to me the most significant was that embroidering has the potential to promote meaningful change because of an intimate and personal companionship that develops within the person and the materials. This relationship has the potential to meet various personal needs and also elicit a variety of potential reactions ().

Victoria: There are two more that I am working on. I haven’t finished the backs yet. When I am doing something very straight forward like that, I know that it would calm me down.

Victoria: For me it was a way to get my mind off other things and to get lost in something, lost in the exploration of what I am working with and the creation. I was doing that one while Karl was in hospital, and I couldn’t go and visit him … not letting me stew and get agitated about what was happening and what I might find when I got there.

The participants’ personal needs included rest, escape, adventure, breaking the rules, sense of self, and connection. Thus, different types of embroidering, diverse in relation to process, tools, and materials, seem to meet varied personal needs. For this reason, embroiderers will inevitably have access to more than one type of project at any one time.

Millicent: My God, it really did save me from real depression. My daughter Jenny was dying, and she became dependent on me. I had to do something while I sat with her for so long … . It gave me a chance to get away for a while. When Jenny died, I was desperately unhappy … . I was so lost … my life was empty … . I needed something to do. I saw an advertisement … for a machine sewing class, so I signed up and the first time I went I found myself whizzing away on a machine. I began to do much more adventurous embroidering. I discarded the iron-on printed patterns, kits, and cross stitch, and started making up my own designs. It saved me then, when I was miserable, and it was just wonderful. I embroidered a cushion which Jenny designed, and I made it up out of old pieces of material from her dresses.

Once an embroidery project is initiated, the embroiderer enters an intimate and personal companionship which combines their minds and bodies together with the tools and materials necessary for practice. The companionship with tools and materials tends to exclude other people but is always connected to the wider social and physical environment.

Becky: My children are used to my physical presence and then having to say two or three times ‘Mum I’m talking to you’. I’m not very good at talking and stitching because I think that I get absorbed in it so.

Olivia: It’s not a lone occupation. It’s like throwing a pebble in a pool.

Once the embroidering relations have been established, the embroiderer will begin to respond in a number of different ways, which become interpreted as meaningful experiences. The participants in this study typically experienced feelings of being absorbed, liberated, addicted, passionate, aesthetically stimulated, calm, or frustrated, depending on the interactions within the embroidering companionship.

Michaela: I do get engrossed in it. I think that is to do with the repetitiveness of it … I find it addictive. Last night I was doing it and I did not realise that I had been sitting on the edge of the chair while I did it, and it wasn’t until I stopped that I thought ‘Oh my back’, I was in so much pain. So, you don’t even feel your body while you are doing it.

Becky: For me it’s tapping into some kind of creativity that other things don’t. I find it really liberating, actually. My head feels big inside when I’m stitching. It’s like unlocking a door and I can feel myself relaxing and I’m letting things just kind of move around in my head, whereas other times I keep them very safely boxed in.

Cessation depended on the intimacy of the relations within the companionship, and the resultant experiences. Wider ‘grand narratives’ could also stimulate and inhibit embroidering practice, most importantly the notion of embroidering as a feminine and amateur construct.

Becky: There are some circumstances where I feel really self-conscious stitching, because I feel really embarrassed about doing it. I am tapping into some kind of stereotype that I don’t want to be. I don’t want to be perpetuating ‘a little woman stitching’ because … that’s not why I am doing it.

Companionship: Intimate relations of body, mind, and materials

The findings suggest that embroidering is an intimate and embodied practice that tends to and can be used to exclude other people. Importantly, embroidering is not being alone; it is being intimately engaged with something that you love, and through it, connecting with both yourself and others. In this way, lone embroiderers might not feel socially isolated because they are linked to the social, cultural, and physical world in a number of important ways through their embroidery.

Becky: What I really love about embroidery is adding in the colours and seeing them work together and building a picture. All these little parts that you put together. It’s very personal and that’s why, even when I am frustrated I just can’t … not pick it up again. It’s really important for me and I take it everywhere and every spare minute, I am thinking about doing it. But actually, my embroidery isn’t important to anybody else. But it’s my favourite thing … If I was cast off to a desert island, that’s what I would have, a radio and just an unlimited supply of threads.

The story above illustrates the intimacy of the companionship and the centrality of the interaction of a person (body/mind) with tools and materials as the essential relations within embroidering. Materials are non-human inanimate entities that are utilised within embroidering. These include natural and synthetic substances such as fabric and threads, but also involves associated phenomena such as colour, texture, weight, tension, and so on. The range of materials used in embroidering are extensive and significant, as is the way they combine to form a picture. Considered agents that enable practice, tools exist in physical form and can be as simple as a needle or complex as a sewing machine, but specifically designed and necessary for accomplishment of a task. The participants, together with tools and materials, had the capacity to influence the other within the embroidering process. Embroidering is thus considered an intra-action of mind, body, tools, and materials. Taken from new materialism, intra-action challenges the concept of ‘interaction’ as an inherent property of an individual human to be exercised, but as a dynamism of forces in which all designated ‘things’ are constantly exchanging and diffracting, influencing and working inseparably (Barad, Citation2007, p. 141).

Companionship: Materials matter

Materials really matter and intimate engagement or intra-action with fabric, threads, beads, colours, texture, shape, and dimension appear to promote a reaction in the embroiderers that can be either immensely pleasurable or repellent. The response, particularly to colour and texture, was evident in all the participants but unique to their personal story. As such it could be based on experience or memories from formative years. The fact that Victoria was taught that natural fabrics were ‘nicer’ than synthetic is still evident in her practice today.

Victoria: Working on cotton organdie and silk is very different. I think that with natural materials the colour is always gentler, whether I have coloured it or whether I buy it that way and so there is something about the feel of it is nicer.

In each case, fabrics, threads, designs, and colours were usually selected or rejected based on their aesthetic appeal to the person. Some attracted and accordingly seemed to promote a deeply satisfying visceral reaction.

Olivia: I started looking at the components that I was enjoying while I was embroidering and my interest in colour is obvious: different contrasts in colour, dark and light and bright and the whole idea of design and shape, and the tactile feeling of different types of thread. I mean, I have got a new kit and it’s going to be beautiful, and it is colour heaven, absolute colour heaven. The feast of colour excites me. I think that is something unique about embroidering – it’s not like a picture – you just want to touch it.

The findings also suggest that the intra-actions with tools and threads can incite implicit, strong, physical, and/or emotional changes. The specific qualities of tools and materials seem to be highly influential, but it is important to remember that they can stimulate both a positive and negative reaction.

Becky: I was given this [freestyle embroidery kit] by my mother. It’s quite simple stitches but the design was so tiny. I had to unpick it because I really didn’t like it. The needle that came with it was too big and I was making huge holes in the fabric, and I couldn’t get the stitches to sit right. The back, it’s a mess, which makes me unhappy, but I have decided just to keep going with it because I did unpick it about three times and then thought maybe I have to see how it goes and actually having done some of it, when you hold it away from you, it’s slightly better than I was expecting it. But when you are looking at it closely, I am not entirely happy.

In the above excerpt from a larger story about the production of a kingfisher embroidery, Becky suggests that, although the recommended stitch was simple, the materials and tools caused a problem in that the design was too small, the thread too fine, and the needle too big. Notice that it was she in action with the needle who was making huge holes in the fabric, which in turn affected the way that the stitches connected to the fabric base and so caused her to unpick them several times. After changing the needle, the story continues in much the same way, with a forward and back stitching and unpicking process with the eventual completion and ultimate fate of a small kingfisher embroidery:

Becky: Would you like to see the kingfisher? He is finished.

Me: So, what are you going to do with this little chap?

Becky: He will go in my box with the other ones (laughing).

Me: But he’s so sweet. … Aren’t you pleased with it?

Becky: If I hold it away from me … I am … actually the colours are okay, aren’t they? His eye is just so huge … are kingfishers' eyes that big?

Me: Have you got a big stash of somewhere, of all the embroideries that you have done?

Becky: Yes, but they are not all together. I just put them somewhere and yes, I have got a fair number.

Me: How many have you got?

Becky: A fair few, hundreds. It’s silly isn’t it … . (quietly). It’s my horde.

Principally, the specific qualities or property held within materiality could promote action or a reaction within the person which then facilitated, obstructed, or sometimes prevented engagement with them. Appreciation of the materials and tools as agents within the intra-active embroidering process appears fundamental to both engagement and continuation of practice.

Companionship: Influence of the body and mind

Consideration of intra-action within the body also appears to be important. Embroidering is done within a body and links mind and body. Essentially, the ‘doing’ of embroidering seems to affect the body, and in turn, the body can affect performance and thus the experience of embroidering. This reciprocal act constitutes part of the embroidering process. Participants’ stories imply that physical restlessness, itchy hands, worry, need for stimulation, fatigue, physical limitations, mental health, mood, and deterioration of capacities and faculties may either stimulate, inhibit, or prevent them from embroidering. For example, now that her eyes are not so good, Becky finds threading the needle to be a real irritation.

Becky: I never used to have a problem but now I really notice that my eyes aren’t as good and even with glasses on it does take me much longer to thread a needle.

Millicent recently experienced a fall, after which she spent some weeks in hospital. She made a good recovery, but she fell on her dominant hand and had no feeling in her fingertips. Handedness is of course significant here, as Millicent was unable to swap hands and still has to try to cut, and stitch, with her preferred hand. She cannot sit unoccupied and will push herself to engage in embroidering projects, but the effect of her physical incapacity is both frustrating in the actual doing as well as in relation to the outcome of her now extensive exertion. Importantly, however, she is still able to accomplish stitching using a sewing machine, as long as she gets someone else to cut out patterns from fabric and can thread the needle herself. Findings from our meetings suggest that machine embroidering as a process requires very little hand dexterity or sensory feedback, which means that Millicent can continue to practice within her limited capacity. She clearly struggles, however, with hand-stitching.

Millicent: When I have made something, I am proud of my achievement, but now there are problems. At the moment, my hand makes it twice as difficult and what I would normally whiz through takes me absolutely ages. I have done this with my gammy hand and the results are disappointing. The [hand] stitching isn’t very good because I have a small semi-circular needle and I couldn’t hold it because it was too small, and I couldn’t feel it, so I used a bigger needle and that was really too big to get very small stitches with a big thick needle. The other day I got so frustrated that I packed the whole damn thing up.

The participants will select embroidering projects in response to body needs. The type of embroidery method employed, combined with the intra-action with specific tools and materials, also appears to promote a different response in the embroiderer but can relate to how the body is feeling.

Embroidering connects hands, eyes, and brain. Mental energy is a clear requirement within the process and can either facilitate or depress performance. For example, mental frustration can stop Millicent from embroidering and this, along with the stories of other participants, suggests that mood is very influential, particularly at the beginning of the activity. There seemed to be a strong consensus that, for the stated benefits that engagement in embroidering to be achieved, participants needed to be in a more positive mind set. Only then could the occupation foster feelings of relaxation, happiness, or freedom from worrying thoughts. Feelings of depression or stress could offset any moves to embroider. This presents a bit of an oxymoron, as illustrated by Michaela.

Michaela: When I am creating, I am happy, and you can see it because I will dedicate time to doing it. When I find little bits, I can tell that I was not at a good stage when I was doing it because it’s half done, or it is done really badly. I have obviously tried to do it and then stopped because it was not happening. Recently, when I was not enjoying my job and I got a bit run down with it, I did try to start embroidering, because I thought that it would make me feel better and being creative is one thing that makes me feel like me. But I can’t when I am bad, I can’t do it. It made me even more angry and upset, so I had to just stop.

Victoria: Sometimes if something is disturbing or concerning me, I find that I can’t do it. The interesting thing with the stuff that I did while Karl was in the hospital was that I had the idea of the pattern before he was poorly and so it became quite a routine exercise. So, what I can’t do if I am in any way distressed or agitated is come up with a design, but I can do the routine of the stitching. But I have also got to be in the mood; it’s about being calm enough to unravel the problem, to tackle it. I think that I need to know that it can be a calm place.

Even when a person’s mood is affable, embroidering seems to promote an internal tension simply because it requires dedicated time. This is because when engaged with an embroidery, it seems very difficult to be doing anything else. Thus, the perceived needs and expectations of other significant characters within a person’s life can hinder the act of embroidering or lead to feelings of guilt, when engaged, which could offset potential benefits. Put simply, because it requires devotion, embroidering can and is often perceived as self-indulgent and selfish.

Michaela: If I do sit and do it [embroidery] of an evening I feel guilty because I feel like I should be cleaning the bathroom or doing some actual work.

Olivia: It takes me somewhere where I know that I am indulging in a way because there are things on the periphery that are saying you really ought to be doing the ironing or Bob [husband] will be here in a minute and you know wouldn’t it be nice if his tea was ready – so there is a little bit of conflict there so I say, ‘I’ll do this for another 20 minutes and then I will go and do all these things that I have got to do’.

In summary, this finding suggests that embroidering as a process can be considered as a captivating, sedentary, embodied companionship that unites mind, eyes, arms, and hands together with tools and materials in the formation of an embroidery. Once a project is in full flow, on the surface, the focal point might appear to be the fabrication of an embroidery. Participants, however, explain that creating an embroidery is much more, and that with some types of embroidering the process can continue beyond completion, simply for the feelings that engagement evokes. The embroidering companionship is difficult to break and thus embroidering constitutes embellishment. Stopping can be a problem.

Michaela: How would you even quantify putting a price on embroidery? When I am pricing up my weaving or knitting it’s very easy. It’s materials used and time, but with embroidery it’s never ending to me … you could just carry on.

Olivia: I enjoyed doing this so much that I didn’t want to finish, so there are hundreds of French knots simply because it was lovely, and I didn’t want to finish it; I was just enjoying being totally absorbed.

Discussion

The findings have shown how embroidering can promote meaningful and intended changes in both physical and emotional state, based on the personal needs of the embroiderer. The health promotion potential offered in embroidering appears to be supported and responsive towards relations in what I present as an intimate intra-active companionship with the person (body and mind) and materials, both of which appear essential and agential in practice. This provides further explanation for findings from previous research that identified the sensory and aesthetic appeal of materials and tools (Brooks et al., Citation2019; Clarke, Citation2020; Cutchin & Dickie, Citation2013; Pöllänen, Citation2015; Riley et al., Citation2013), which was seen to motivate continued engagement, but criticises the perceived need for mastery and control over material objects. Pöllänen (Citation2015) found that craft-makers developed a sense of agency through ownership of a craft project, with associated feelings of mastery over materials. Significance of the influence of the effect of personal agency seems to be apparent in previous research (Clarke, Citation2020; Riley, Citation2011), but limited in relation to understanding mutual action with materials. What has been described within previous research, seems relatively one way, the body’s action over or despite materials. Importantly, in this study materials and person are in a reciprocal relationship.

My findings further question the dominant idea that social engagement is a major factor in the health potential of arts, crafts, and textiles. Contrariwise, I argue that although embroidering can meet the need to be connected to wider society, this is not through direct social engagement, but undertaken through an intimate, habitual, and compelling craft-making companionship, usually within the home. This suggests an unrealised value in home-based occupations. Social detachment with exclusion of other people is considered as a necessary and important aspect of the health potential.

The strong emotion of passion or love that was conveyed through my participants’ embroidering experience appears to relate to a deep and intimate personal relationship with the materials and essentially how they intermingle through the embroidery process in intra-action with the body. Previous research has revealed the experience of joy in craft making (Gauntlett, Citation2011), but not necessarily love. The possibilities offered in embroidering have been indicated as internal to the process, which incorporates a passionate and intimate body, mind, and material companionship. Primarily, this is considered as the means or potential for meaningful change in embroidering. The implication is that the intra-actions in this association need to be congenial, but not necessarily without trouble, in order to form the essential relations necessary for embroidering to establish and flourish within a person’s life.

The notion of ‘companionship’ presented assumes Frank’s (Citation2010) extension of Donna Haraway’s non-human companion, which he associates with the purpose of stories as companions. Here, my suggestion is that embroidering becomes a companion, and this relates not to the relationship between person and object in the form of the materials and tools but reciprocal intra-action. This might be why they can become symbolic of the person who made them (Dickie, Citation2011) and appear so hard to give away. Each embroidery ‘holds’ the person in the story of its construction, and this engagement at a distance can be considered as an entanglement (Barad, Citation2007). In the development of such an intwined affiliation, the person and product become inseparable. Entanglement can be said to occur through deep and sustained engagement with embroideries, even when physically separated.

The importance of materials in embroidering became increasingly significant through the method of narrative analysis undertaken in my study. Viewed via a narrative lens, objects can be seen to have agency (Frank, Citation2010). From a narrative perspective, a material object such as fabric can act, and thus can have agency in relation to human engagement. Through narrative analysis I began to realise that materials and tools were significant actors in the process of embroidering. This means that a person can distress, move, touch, manipulate, disturb, imitate, engage, or mark materials, tools, and vice versa. A character is a person who has agency through a body, which includes the physical and emotional mind. A person is thus embodied and exists as both object and subject (Kielhofner, Citation2009). Yerxa (Citation2009) explained this as the embodied self which consists of the ‘I’ and the ‘it’. Specifically, this illustrates the crucial prominence of the intra-action of participant’s ‘self’ with their bodies, tools, and materials as the essential relations within embroidering. Principally, this suggests that the participants became active characters, together with their bodies, tools, and materials as equally dynamic agents, as each has the capacity to influence the other. The collaborative relations offered in embroidering means that the intra-action of character to agent and agent to character promote different outcomes.

Materials such as fabric, threads, beads, colours, texture, shape, and dimension appear to promote a bodily response that can be either immensely pleasurable or equally frustrating or even repellent. It seems that occupational engagement is partly dependent of the aesthetic and haptic appeal of materials. Consideration of materials as agents in occupations may be fundamental to understanding how engagement can influence health. A feature of crafts, perhaps more than ‘art’, is the focus on a deep, agential relationship with materials.

Published research appears overwhelmingly positive about the effects of engaging in crafts and textiles, suggesting that engagement is stress-reducing (Pöllänen, Citation2015) and enhances well-being (Pöllänen & Voutilainen, Citation2018). These positive emotions are purported to relate to personal agency and self-efficacy. Likewise, my findings are principally ‘positive’, but this was because the participants were genuinely very confident that their embroidering enhanced their well-being. They also knew that I was particularly interested in this idea and so they may have over-emphasised the connection. But at times my participants shared that they got frustrated. This was related to the agency of both body and materials as actors in the stitching collaboration.

My findings encourage the idea that, for successful performance and perhaps to promote health, tools and materials need to be appropriate, engaging, available, accessible, and fit for purpose. Threads could become temperamental, embroidery backs (reverse side) were ‘messy’, the needle ‘too big’, and the resulting holes in the fabric unappealing, which promoted unpicking and re-stitching. Other reasons included low mood, overwhelming worry, the piece not coming together, ambiguous instructions, or being too self-critical, all perceived within wider ‘grand narratives’. Clearly, embroidering is not always a pleasurable experience. Frustration is considered to relate to problems that inhibit the more congenial intra-action of body, materials, and tools when embroidering. It seems that if one element of the material, brain, and body cooperation is problematic, then trouble occurs. Experience of materials and the body as agents within the embroidering process appears fundamental to both engagement and continuation of practice.

In summary, I am arguing that embroidering can be interpreted as an important and meaningful liaison where the boundaries between person, body, materials, and tools become blurred. Csikszentmihalyi (Citation1998) implied that optimal experience can be accompanied by loss of the sense of self as separate from the world through union with the (natural) environment. This is combined with a sense of seemingly effortless bodily movement and the reaction of wanting the action to go on forever. In this way, the needle and thread, for example, becomes part of the body within the act of stitching. One is not complete within the moment of action without the other. They are inseparable, which further indicates the possibility of an entanglement.

Csikszentmihalyi (Citation1998) indicated the significance of the close (but not inseparable) kinship between an individual and the natural world. He suggested that loss of thinking about the self (often termed as ‘self-forgetting’) is based on real experience with real phenomena moving together towards a common goal. When a person invests their psychic energy into an interaction, they become part of that greater system of action (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation1998). Through this interaction, the self expands its boundaries and becomes more complex. Fundamentally, the cooperation of person with their environment is considered as extremely enjoyable if it requires continued opportunities for skill development. Flow theory was developed through research into occupations within the natural environment, such as gardening and rock climbing, based on the understanding that they require few man-made material resources (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation1998). In this respect the theory offers some explanation but still undervalues fabricated material items.

My findings suggest that consideration of embroidering materials as agents is important and that intimate collaboration with them might be a significant condition for optimal engagement. Rather than being separate from the wider systems within which humans exist, people are part of them and need to recognise the limitations of human will and accept a cooperative rather than ruling role in the universe (Barad, Citation2007; Braidotti, Citation2016). Barad’s (Citation2007) theory of intra-action questions the notion of causality and the concept of individualism, instead offering the idea that where individual entities exist, they are not individually determinate but co-exist within a phenomenon, which in this case is the occupation of embroidering. Accordingly, embroidering is proposed as an entanglement—the ontological inseparability of intra-acting agencies (Barad, Citation2007). In embroidering, the embroiderer can feel that they exist in something greater (Gauntlett, Citation2011; Parker, Citation2010), such as the wider world. Occupational science to date does not seem to adequately consider the importance of material companionship within occupational engagement, and this is something that requires further attention in order to understand the influence on health and well-being.

Limitations

The study was located in the United Kingdom and involved participation of five self-selected women who regularly embroidered. The process of analysis was developed for the study and as such is unverified. As a PhD student, I was personally accountable for and intimately involved in the research process, and this should be considered as a limitation. Collection of data over a period of 6-months is considered a strength that enabled a rich, detailed, and credible account of the experience of embroidering situated in everyday life. The study does not intend to generalize but offers trustworthy findings that will resonate with other experienced embroiderers. The findings need to be considered in the light of embroiderers who were extremely passionate about their craft.

Conclusion

Through narrative inquiry, this research established a deep understanding of the experience of embroidering through the essential concept of an intimate and reciprocal material/body/mind companionship. In the development of such a close affiliation, and in combination with the complexity of the evoked relations, the person and product become inseparable. The concept of entanglement is suggested to occur through deep, focused, and sustained mutual engagement and is presented as the centre for any health promoting potential. Acknowledging materials and tools as agents is considered essential, in order to adjust the experience and modulate occupational engagement. More than a diversion from a life situation, the power of the embroidering companionship offers absorption and liberation or an opening of possibilities, which departs from relations imposed by others (Fox, Citation2012).

There are several implications for occupational science. First, the study endorses embroidering as a means to promote health and well-being through an intimate and entangled companionship of mind/body/material with understanding of significance of agency of materials on engagement and on becoming other through occupation. Second, embroidering involves a diversity of techniques, which people seem to use purposely to regulate their physical and emotional health and well-being. Third, embroidering can be considered as a co-occupation; being with something that you love and feeling connected to the wider world, which challenges the negative view of solitary occupation.

Disclosure Statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

References

- Adey, K. L. (2018). Understanding why women knit: Finding creativity and flow. Textile, 16(1), 84–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/14759756.2017.1362748

- Andrews, M., Squire, C., & Tamboukou, M. (Eds.). (2013). Doing narrative research (2nd ed.). Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526402271

- Astley-Cooper, H. (1941). Some reflections on occupational therapy. Journal of Association of Occupational Therapists, 4(9), 9–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/030802264100400910

- Banks-Walker, H. (2019). Why embroidery is sew hot right now. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/01d8b11a-e9b7-11e9-a240-3b065ef5fc55

- Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe half way: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Duke University Press.

- Bonsall, A. (2012). An examination of the pairing between narrative and occupational science. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Science, 19(1), 92–103. https://doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2011.552119

- Braidotti, R. (2016). The posthuman. Polity Press.

- Brooks, L., Ngan Ta, K.-H., Townsend, A. F., & Backman, C. L. (2019). “I just love it”: Avid knitters describe health and well-being through occupation. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 86(2), 114–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417419831401

- Bruner, J. (1990). Acts of meaning. Harvard University Press.

- Clandinin, J. D., & Connelly, M. F. (2000). Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research. John Wiley & Sons.

- Clarke, N. A. (2020). Exploring the role of sewing as a leisure activity for those aged 40 years and under. Textile, 18(2), 118–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/14759756.2019.1613948

- Cox, P. (1947). Occupational therapy with the tuberculosus patient. Journal of the Association of Occupational Therapists, 10(29), 7–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/030802264701002929

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1998). Flow: The psychology of happiness. Rider.

- Cutchin, M. P., & Dickie, V. A. (Eds.). (2013). Transactional perspectives on occupation. Springer.

- Demecs, P., & Miller, E. (2019). Woven narratives: A craft encounter with tapestry weaving in a residential aged care facility. Art/Research International, 4(1), 256–286. https://doi.org/10.18432/ari29399

- Dickie, V. A. (2011). Experiencing therapy through doing: Making quilts. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health, 31(4), 209–215. https://doi.org/10.3928/15394492-20101222-02

- Dickie, V., Cutchin, M. P., & Humphry, R. (2006). Occupation as transactional experience: A critique of individualism in occupational science. Journal of Occupational Science, 13(1), 83–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2006.9686573

- Fancourt, D., & Finn, S. (2019). What is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being? A scoping review. WHO Regional Office for Europe.

- Fox, N. (2012). The body. Polity.

- Frank, A. W. (2010). Letting stories breathe: A socio-narratology. University of Chicago Press.

- Gauntlett, D. (2011). Making is connecting: The social meaning of creativity, from DIY and knitting to YouTube and Web 2.0. Polity Press.

- Harris, J. (2011). 5000 years of textiles. Smithsonian Books.

- Hunter, C. (2019). Threads of life: A history of the world through the eye of a needle. Hodder & Stoughton.

- James, G. W. B. (1940). A reprint of notes on shell-shock cases. Journal of the Association of Occupational Therapists, 3(7), 7–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/030802264000300703

- Jefferies, J. (2016). Crocheted strategies: Women crafting their own communities. Textile: Cloth and Culture, 14(1), 14–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/14759756.2016.1142788

- Josephsson, S., & Alsaker, S. (2015). Narrative methodology: A tool to access unfolding and situated meaning in occupation. In S. Nayar & M. Stanley (Eds.), Qualitative research metholologies for occupational science and therapy (pp. 70–83). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203383216

- Kenning, G. (2015a). Creative craft-based textile activity in the age of digital systems and practices. Leonardo, 48(5), 450–456. https://doi.org/10.1162/LEON_a_00907

- Kenning, G. (2015b). “Fiddling with threads”: Craft-based textile activities and positive well-being. Textile, 13(1), 50–65. https://doi.org/10.2752/175183515 × 14235680035304

- Kielhofner, G. (2009). Conceptual foundations of occupational therapy practice (4th ed.). F. A. Davis.

- Kohler Riessman, C. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. Sage.

- MacDonald, E. M. (1938). Bookbinding and craft in occupational therapy. Journal of the Association of Occupational Therapists, 1(1), 23–25.

- McBrinn, J. (2017). Queer hobbies: Ernest Thesiger and interwar embroidery. Textile, 15(3), 292–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/14759756.2017.1294827

- Parker, R. (2010). The subversive stitch: Embroidery and the making of the feminine (3rd ed.). I. B.Tauris & Co.

- Polkinghorne, D. E. (1995). Narrative configuration in qualitative analysis. Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 8(1), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/0951839950080103

- Pöllänen, S. (2015). Crafts as leisure-based coping: Craft makers’ descriptions of their stress-reducing activity. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 31(2), 83–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212X.2015.1024377

- Pöllänen, S., & Voutilainen, L. (2018). Crafting well-being: Meanings and intentions of stay-at-home mothers’ craft-based leisure activity. Leisure Sciences, 40(6), 617–633. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2017.1325801

- Ricoeur, P. (1984). Time and narrative. Chicargo Press.

- Riley, J. (2011). Shaping textile making: Its occupational forms and its domain. Journal of Occupational Science, 18(4), 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2011.584518

- Riley, J., Corkhill, B., & Morris, C. (2013). The benefits of knitting for personal and social wellbeing in adulthood: Findings from an international survey. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 76(2), 50–57. https://doi.org/10.4276/030802213X13603244419077

- Smith, M. (1945). Occupational therapy in a spinal injury centre. Journal of the Association of Occupational Therapists, 8(22), 14–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/030802264500802210

- Thornely, G. (1948). The rehabilitation of German wounded ex-servicemen: A British Red Cross scheme. Journal of the Association of Occupational Therapists, 11(33), 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/030802264801103310

- Willis, J., Muktha, J., & Nilakanta, R. (2007). Foundations of qualitative research: Interpretive and critical approaches. Sage.

- Wood, Z. (2020). A good yarn: UK coronavirus lockdown spawns arts and craft renaissance. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2020/may/04/a-good-yarn-uk-coronavirus-lockdown-spawns-arts-and-craft-renaissance

- Yerxa, E. J. (2000). Occupational science: A renaissance of service to humankind through knowledge. Occupational Therapy International, 7(2), 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1002/oti.109

- Yerxa, E. J. (2009). Infinite distance between the I and the it. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63(4), 490–497. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.63.4.490