ABSTRACT

Background:

Occupational science scholarship has long recognized the relationship of person, occupation, and context, with less focus on the role of occupation in placemaking. Inquiries about ‘third places’ beyond home and work can develop knowledge about how occupations help (re)create and maintain places; such knowledge is especially relevant for understanding how people navigate precarious social and economic conditions.

Methods:

Through a 5-step scoping review, we surveyed the state of knowledge about ‘third places’ and the roles they play in the lives of precariously employed individuals. Our review covered English-language literature published between 2012 and 2022 that was indexed in eight academic journal databases. We descriptively and thematically analyzed 24 multidisciplinary articles.

Findings:

Included articles were concentrated among relatively few disciplinary, geographical, and methodological bases. Within these studies, situations of financial precarity and social exclusion prompted precarious workers to access and create alternative physical and virtual third places; these third places were characterized by having low barriers to entry, affording diverse forms of participation, and engendering few obligations or commitments. Occupations occurring through these places played a central role in placemaking and reflected the multifaceted purposes of third places and the diverse needs experienced within precarious lives.

Implications:

These findings support the need to reconceptualize ‘third places’ in ways that attend to occupation and foreground inclusionary and exclusionary potentials. Further research on third places can extend occupational science theorization of dynamic person-occupation-place relationships and advance interdisciplinary social transformation efforts through occupation-based community development work.

RESUME

Contexte : la recherche en sciences de l'occupation reconnaît depuis longtemps la relation entre la personne, l'occupation et le contexte, mais s'intéresse moins au rôle de l'occupation dans la création de lieux. Les enquêtes sur les “tiers lieux” au-delà du domicile et du travail peuvent permettre d'acquérir des connaissances sur la manière dont les occupations contribuent à (re)créer et à maintenir des lieux ; ces connaissances sont particulièrement utiles pour comprendre comment les gens s'adaptent à des conditions sociales et économiques précaires. Méthodes : par le biais d'un examen de la portée en cinq étapes, nous avons examiné l'état des connaissances sur les “tiers lieux” et les rôles qu'ils jouent dans la vie des personnes ayant un emploi précaire. Notre étude a porté sur les écrits en langue anglaise publiée entre 2012 et 2022 et indexés dans huit bases de données de revues universitaires. Nous avons analysé de manière descriptive et thématique 24 articles multidisciplinaires. Résultats : les articles inclus étaient concentrés sur un nombre relativement restreint de fondements disciplinaires, géographiques et méthodologiques. Dans ces études, les situations de précarité financière et d'exclusion sociale ont incité les travailleurs et travailleuses précaires à accéder à des tiers-lieux physiques et virtuels et à en créer ; ces tiers-lieux se caractérisent par de faibles barrières à l'entrée, des formes de participation diversifiées et peu d'obligations ou d'engagements. Les occupations exercées dans ces lieux ont joué un rôle central dans l'aménagement de l'espace et ont reflété les objectifs multiples des tiers-lieux et les divers besoins des personnes en situation de précarité. Implications : ces résultats confirment la nécessité de reconceptualiser les “tiers lieux” en tenant compte de l'occupation et en mettant en avant les potentialités d'inclusion et d'exclusion. Des recherches plus approfondies sur les tiers lieux peuvent étendre la théorisation des sciences de l'occupation sur les relations dynamiques personne-occupation-lieu et faire progresser les efforts interdisciplinaires de transformation sociale par le biais d'un travail de développement communautaire fondé sur l'occupation.

Conceptions of place have long influenced occupational science theories and research (Delaisse, Huot, & Veronis, Citation2021) as part of the discipline’s historical attention to contexts and environments (Hocking, Citation2021). Considered by some to be distinct from generic ‘space’ by virtue of associations with meaning (Cresswell, Citation2015; Rowles, Citation2008), ‘place’ is more than a mere location in the world: it is a process forged through people’s actions as they go about living (Akbar & Edelenbos, Citation2021). Occupational science inquiries have explored a range of places, from residences (e.g., Gonçalves & Malfitano, Citation2020; Hand et al., Citation2023; Heatwole Shank & Cutchin, Citation2010) and workplaces (e.g., Jakobsen, Citation2004; Ross, Citation1998) to community locations (e.g., Hand et al., Citation2018; Hart & Heatwole Shank, Citation2016; Huot & Veronis, Citation2018; Kantartzis & Molineux, Citation2017; Peralta-Catipon, Citation2009; Wicks, Citation2014) and online environments (e.g., McCarthy et al., Citation2022), with less focus on the dynamic process of placemaking (Johansson et al., Citation2013). Understanding how occupation continually contributes to the (re)creation and maintenance of place can bolster attention to placemaking within the discipline and further elucidate the situated and co-constitutive nature of occupation (Dickie et al., Citation2006; Laliberte Rudman & Huot, Citation2012; Madsen & Josephsson, Citation2017).

In pursuing deeper understandings of occupation-place relationships, occupational scientists can contribute to wider scholarship on ‘third places’ wherein people congregate, interact, and spend time outside of home (‘first place’) and work (‘second place’) (Oldenburg, Citation1999). Third places originally became a focus of scholarly concern in the 1980s due to fears about their disappearance from American middle-class suburban landscapes (Oldenburg, Citation1989; Oldenburg & Brissett, Citation1982). While the physical or structural features of third places are not insignificant, the importance of these places was primarily asserted in relation to their socially supportive nature, including their affordance of “pure sociability” (Oldenburg & Brissett, Citation1982, p. 273) and function as social ‘levelers’ (Oldenburg, Citation1999, p. 24) across members of the general public regardless of social status. Coffee shops, pubs, and libraries have often been studied within research on third places; gyms, virtual sites, community gardens, and forms of public transit have also been explored (Dolley & Bosman, Citation2019).

Academics, policy makers, and public health professionals have continued to frame third places as playing a potentially vital role within contemporary society. Third places have been particularly heralded relative to concerns regarding decreasing social cohesion and social connectedness, both of which have been tied to increasing urbanization and widening social inequities (e.g., Finlay et al. Citation2019); often, these concerns are framed around the experiences of people living in economically depressed neighborhoods in middle- to upper-income countries (Hickman, Citation2013; Williams & Hipp, Citation2019). Although the need for third places continues to be recognized, scholars have recently critiqued the concept of ‘third places’ by noting that the original conception overly relied on experiences, places, and social ties relevant to white, American, male, full-time employed, and middle-class individuals (Dolley & Bosman, Citation2019; Fullagar et al., Citation2019; Littman, Citation2021). As such, extant research has tended to dismiss tensions and exclusionary factors relevant to third places, assumed people’s home and work lives are distinct, and overemphasized sociability while overlooking what people do in third places beyond conversation.

Contemporary social and economic conditions further underscore the need to enhance inquiries about third places. Precarity—defined broadly as the pervasive experience of uncertainty, instability, inequality, and insecurity—has become increasingly common across many sociopolitical contexts and life domains (Grenier et al., Citation2017; Harris & Nowicki, Citation2018; Kwon & Lane, Citation2016; Waite, Citation2009). Understanding precarity requires attending to the spaces and places of everyday life (Muñoz, Citation2018), wherein changes to access and control manifest the degrees of precariousness that people experience. Such changes are evident in research findings about precarious employment (e.g., Lewchuk & Laflèche, Citation2017) and long-term unemployment (e.g., Huot et al., Citation2022) as well as the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., Czech et al., Citation2021). Foregrounding precarious circumstances in research on third places presents an opportunity to more fully understand how such places do and do not meet needs for diverse individuals and communities, particularly people experiencing social marginalization and inequities.

The concept of third places was introduced in occupational science research through Kantartzis’ (Citation2016) study of occupation in a Greek town (also described in Kantartzis & Molineux, Citation2017); however, the only other apparent uptake of the concept of third places in occupational science literature comes from urban planners (Thompson & Kent, Citation2014) who contributed to a special issue on occupation and population health (Wicks, Citation2014). We suggest that greater focus on third places can be fruitful for occupational science, both for extending understandings about the role of occupation in placemaking and for providing another pathway for interdisciplinary scholarship, advocacy, occupation-based social transformation, and policy making. To inform an ongoing funded ethnographic project, we conducted a scoping review to understand the state of knowledge regarding third places and their roles in the lives of people facing precarious employment circumstances. Precarious employment circumstances defined by irregular and unpredictable temporal, contextual, and financial characteristics and a lack of stable ‘second’ (i.e., work) places affect the broader social lives of people who experience them, as well as their families and communities (Lewchuk & Laflèche, Citation2017; Popov & Solov’eva, Citation2019). People facing precarious employment circumstances fall outside the original referent group for the concept of third places, and their growing numbers in contemporary society (cf. Lewchuk et al., Citation2016) and challenges with social participation (Bajwa et al., Citation2018; Popov & Solov’eva, Citation2019) make their experiences especially relevant for filling gaps in knowledge about third places. Within this paper, we draw upon our scoping review about third places, precarious workers, and social isolation to provide an overview of the current knowledge base while also highlighting contributions and further opportunities to develop and apply occupational science understandings of placemaking, collective occupation, and the community orientation of a transactional perspective.

Methods

This scoping review followed the five-step process outlined by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005), updated by Levac et al. (Citation2010), and further refined by Pham et al. (Citation2014), Colquhoun et al. (Citation2014), and Peters et al. (Citation2020) to map existing knowledge and identify gaps in literature about the role of third places vis-a-vis precarious workers’ social connection and isolation. As required by the funding mechanism supporting this study, we focused our scoping review on knowledge published in the past 10 years (i.e., between 2012 and 2022). Though not a requirement of scoping reviews, we also evaluated the quality of included articles (Brien et al., Citation2010; Hand & Letts, Citation2009; Pham et al., Citation2014) to deepen our assessment of knowledge gaps. Drawing on methods aligned with critical interpretive synthesis (Benjamin Thomas & Laliberte Rudman, Citation2018; Dixon-Woods et al., Citation2006), we further critically examined the assumptions and questions that guided included studies and identified alternative assumptions that might open up new or expanded possibilities for knowledge generation.

To ensure optimal capture of relevant studies and comprehensive analysis and interpretation of findings, our scoping review followed an iterative, data-driven process (Levac et al., Citation2010; Peters et al., Citation2020). We used Covidence, a web-based collaboration platform, to manage study screening, study selection, and data extraction, thus enabling research team members’ cross-site involvement in the scoping review. The research team included two primary researchers (Laliberte Rudman and Aldrich), three doctoral-level student trainees (Akrofi, Fernandes, and Nguyen), one master’s-level student trainee (Larkin), and one undergraduate-level student trainee (Moran).

Step 1: Identification of research question (March 2022)

The following research question guided this scoping review: What is known about the types and characteristics of ‘third’ places that help maintain social connectedness and ameliorate social isolation in the lives of people experiencing precarious employment circumstances? Consistent with the aim of scoping reviews (Colquhoun et al., Citation2014; Levac et al., Citation2010), our guiding research question broadly identified the target group, central concept, and outcomes of interest. For the target group (i.e., persons facing precarious employment circumstances), defining qualities included participation in work that was transient, non-permanent, unpredictable, having few worker protections or rights, and/or associated with low or unpredictable remuneration; this group included people experiencing cyclical or long-term unemployment. We defined the central concept of third places following Oldenburg (Oldenberg, Citation1999; Oldenburg & Brissett, Citation1982) and others (e.g., Finlay et al., Citation2019) to include physical and virtual places outside of home and work that facilitate social interaction, connection, and support. We broadly conceptualized our outcomes of interest, social connectedness and social isolation, to account for overlap with related terms (see ). Thorough understanding of the research question served as the basis for our search strategy development.

Table 1. Definitions of concepts comprising research question

Step 2: Identification of relevant studies (April-June 2022)

The two primary researchers and two of the doctoral-level trainees (Akrofi and Fernandes) met consistently throughout the development and implementation process to discuss, clarify, and refine the search strategy. After several iterations of preliminary searches and consultation with a Western University librarian, we developed a comprehensive list of relevant search terms that captured a broad, flexible understanding of place; the diversity of terms describing social experiences and outcomes; and the complexity of precarious employment experiences. Together, one of the primary researchers (Laliberte Rudman) and two of the doctoral-level trainees (Akrofi and Fernandes) tested, refined, and finalized the search strategy, carefully documenting details and recording changes (Peters et al., Citation2020). illustrates the final list of keywords entered into each database, including Boolean operators and asterisks representing truncations, as well as subject terms corresponding to each topic category (i.e., ‘precarious work’, ‘social’, ‘place’).

Table 2. Keyword and subject heading terms

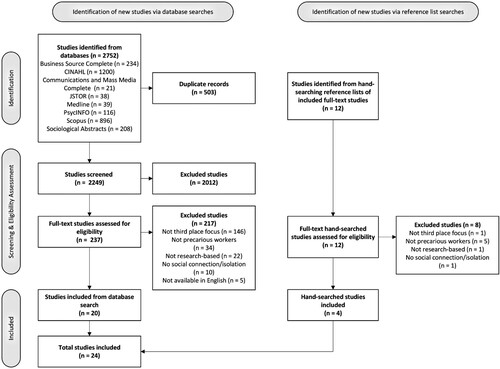

We searched literature in the following eight databases: Scopus (multidisciplinary), CINAHL (allied health), PsycINFO (psychology), Sociological Abstracts (social sciences), Medline (biomedical sciences), JSTOR (multidisciplinary), Communications and Mass Media Complete (communications), and Business Source Complete (multidisciplinary business). To ensure consistency and understanding of the search process, the doctoral-level trainees conducted parallel searches in three alternatively powered databases before dividing the remaining databases and conducting searches independently. The doctoral-level trainees exported results from each database search and the undergraduate-level trainee (Moran) imported those results into Covidence for screening. Using Covidence, we documented the number of records obtained and processed and developed and revised a PRISMA flow chart () during each subsequent step (Pham et al., Citation2014). We identified 2,752 total records through the database searches, 503 of which were duplicates that we removed prior to study selection.

Step 3: Study selection (July-August 2022)

We reviewed articles using a two-phase selection process (Peters et al., Citation2020; Pham et al., Citation2014) beginning with title and abstract screening and proceeding to full-text screening. We identified inclusion and exclusion criteria to guide title and abstract screening (see ) and used them to create and test a screening form.

Table 3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for scoping review

Two of the doctoral-level trainees (Akrofi and Fernandes) independently screened each of the 2,249 citations, recording their decisions (yes/no/maybe) in Covidence and documenting reasons for exclusion as well as any uncertainties about their decisions. One primary researcher (Laliberte Rudman) resolved disagreements between the trainees’ decisions. Both primary researchers then independently reviewed the full text of each of the remaining 237 documents that passed phase one screening. Using a similar process to phase one of this step, one team member (Fernandes) resolved disagreements between the primary researchers’ full-text screening decisions. We documented reasons for excluding 217 articles at the full-text screening stage (see ), leaving 20 articles eligible for inclusion. The two doctoral-level trainees then hand-searched the reference lists of those 20 articles to identify additional relevant studies not captured through database searches. We identified 12 additional articles and included four of those articles after repeating the full-text review process described above, resulting in a combined total of 24 included articles moved forward to data extraction.

Step 4: Data extraction and critical appraisal of research (August-September 2022)

The two primary researchers worked with the undergraduate trainee to develop a data extraction form in Covidence. Key sections of this form included: a) descriptive characteristics of the article (e.g., citation information, geographical location of research, disciplinary location of authors); b) research characteristics (e.g., research purpose, methodology, methods, findings, key interpretations); c) sample characteristics, and d) research quality. We used Tracy’s (Citation2010) eight appraisal criteria as the basis for qualitative article extraction form fields, and worksheets from the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (Citation2021) to develop extraction form fields for quantitative and mixed methods studies. One primary researcher (Laliberte Rudman), one doctoral-level trainee (Fernandes), and one master’s-level trainee (Larkin) piloted the extraction form on two articles to ensure clarity and consistency in extraction results (Colquhoun et al., Citation2014); after refining the form, those two trainees evenly divided the remaining articles, extracting data from and assessing the quality of each article. Each primary researcher checked one trainee’s extraction results to ensure extraction quality for every included article.

Step 5: Collating, summarizing, and interpreting findings (October - November 2022)

With guidance from the primary researchers, the master’s-level trainee (Larkin) and another doctoral-level trainee (Nguyen) organized the results from each data extraction category into separate word processing documents. Initial descriptive analyses of the data set entailed identifying and summarizing quantifiable data (e.g., geographical locations of the studies, types of third places, types of methods used). Drawing on critical interpretive analysis techniques (Benjamin Thomas & Laliberte Rudman, Citation2018; Dixon-Woods et al., Citation2006) and a thematic analysis approach (Harris et al., Citation2018; Lightfoot et al., Citation2018), the primary researchers then independently coded the remaining word processing documents that did not contain quantifiable data. The primary researchers compared their inductive codes for data related to types and characteristics of third places, social experiences and outcomes occurring in third places, occupations occurring in third places, and key interpretations and implications of included articles. To facilitate comparison, the primary researchers made reflexive notes and met regularly to discuss and refine their codes, themes, and critical interpretations. Once they refined their analytic approach, the primary researchers divided the remaining data and completed independent analyses.

Findings

For this manuscript, we briefly share findings about the broader article set before presenting findings of relevance to occupational science, including the relation of third place types and characteristics to occupational engagement and the contributions of occupational engagement to the (re)making of third places in precarious circumstances.

Descriptive characteristics, research quality, and critical analysis of research foci within article set

Researchers affiliated with institutions in the United Kingdom, Australia, and the United States were most prevalent across the 24 publications included in this scoping review, and researchers’ disciplinary affiliations were concentrated among sociological (n = 8), geographical (n = 5), and anthropological (n = 3) perspectives. Researchers’ affiliation locations were not always aligned with the geographic sites of their studies, resulting in a greater number of inquiries in Asia (n = 9) as compared to Europe (n = 6) or North America (n = 4). Twelve studies focused on the experiences of foreign temporary migrant workers, while the remaining studies focused on people’s experiences across a range of employment types, including gig, contract, freelance, entrepreneurial, day labor, seasonal, and low-skilled work.

Research quality was challenging to assess for this article set. Theoretical frameworks and participant demographics were not uniformly reported across the 24 articles. Ten of the 24 articles did not specify a research methodology, but 12 of the remaining articles reported utilizing ethnographic methodologies; similarly, three articles did not specify a sample size, but 13 of the remaining articles reported sample sizes of fewer than 40 participants. Overall, 14 of the 24 articles omitted some information that was necessary to fully appraise research quality, with a lack of clarity regarding analytical approaches (n = 9) and researcher reflexivity (n = 8) most frequent across the article set. Accordingly, concerns about research rigor (n = 14), sincerity (n = 11), and credibility (n = 6) are limitations of this article set, although some of the missing information may be attributable to differing writing conventions across disciplines and journals rather than poor research quality.

Variance in disciplinary perspectives, languages, and writing conventions also likely contributed to the range of research questions and purpose statements in this article set. Some articles featured direct research questions and purpose statements while others broadly pointed toward issues of interest. Likewise, the group of articles evidenced a variety of topical foci, consistent with the multiple disciplinary perspectives held by article authors. Across explicitly and implicitly stated research foci, these studies largely conveyed a descriptive intent, with lesser focus on critiquing prevailing knowledge or attending to issues of power. The primary foci and assumptions of this article set included: agency enacted by precarious workers to meet needs; experiences of social marginalization and exclusion; social needs and relations for people experiencing precarity; and places as venues for conflict and resistance. Articles focused on precarious workers’ agency primarily aimed to describe how workers engaged with places to meet particular needs, as in Straughan and Bissell’s (Citation2021) exploration of “generative sociality” and “practices of social curiosity” (p. 3) via gig work applications among urban Australian gig workers, or Petrou and Connell’s (Citation2019) study of ni-Vanuatu seasonal migrant workers in Australia who used Facebook to enact “their own human agency to achieve solutions, put in place warnings, advise on trends and maintain useful social contact to negotiate the inherent power imbalances that characterise guestworker schemes” (p. 117). Combining a similarly descriptive approach with some attention to power relations, some articles elucidated aspects of lived experience that shaped social marginalization: for instance, Wu’s (Citation2021) study explored “the social costs of labour migration” (p. 313) and “constraints on social support opportunities” (p. 314) for Timorese seasonal agricultural workers in Australia, and Hamid and Tutt (Citation2019) illustrated the “exclusionary social practices” (p. 513) targeted at Tamil migrant construction workers in Singapore.

Evidencing a more pronounced critical perspective, other articles analyzed differences in the needs and social relations of precarious workers given their social marginalization and limited resources. For example, Bonner-Thompson and McDowell (Citation2020) studied how caring practices emerged among young men who lacked the financial resources to access typical social spaces such as bars and arcades in coastal English towns; Kudejira (Citation2021) explored food sharing practices as a mediator of social relations among lesser resourced “undocumented Zimbabwean farmworkers and other Zimbabwean migrants” (p. 17) in South Africa. Demonstrating an explicitly critical positioning, some studies began from the premise that micro-politics of space are situated within larger social relations that shape place-based governing and surveillance; examples of this focus were evident in Aquino et al.’s (Citation2020) examination of temporary migrant workers’ engagement in outdoor informal team sports in relation to their inclusion and exclusion experiences in Singapore, as well as Piocos’ (Citation2019) assertion that marginalized Filipina and Indonesian domestic workers’ use of public squares to assert their identities in Hong Kong revealed “how space is a contested arena” (p. 164). Overall, these framings illuminated assumptions regarding the kinds of precarious workers that researchers deemed important to study; what challenges those workers were imagined to face; and what kinds of problems were framed as needing to be resolved through place relative to precarious workers’ social and spatial experiences. Omissions and opportunities for expanding on these assumptions will be addressed in the discussion section below.

Types and characteristics of third places and their relationship to occupational engagement

Although only 2 of the 24 articles included in this scoping review directly referenced the concept of ‘third places’, all of the articles reported salient findings about a variety of third places (see ).

Table 4. Study characteristics in relation to findings

Some places, including dining establishments and stores, resembled Oldenburg’s (Citation1989) original conception of third places while others, such as social media groups and community centers, reflected the expanded foci evident in contemporary research (cf. Dolley & Bosman, Citation2019). Many of the dining establishments and stores described in the articles were framed as places missing from people’s lives due to increased precarity, as in Bonner-Thompson and McDowell’s (Citation2020) discussion of bars for young men living in seaside English towns. In the absence of temporal stability and sufficient resources to access such places, precarious workers sometimes switched to using places that required no fee for use, such as in Tungohan’s (Citation2017) findings regarding Filipino temporary migrant workers’ use of community centers in Canada. Greater diversity in types of places being used also resulted from social marginalization or attempts to manage social exclusion from mainstream third places, as Tungohan (Citation2017) also reported when explaining how xenophobic attitudes in some public places reinforced Filipino migrant workers’ choices to gather in community centers instead. A number of alternative third places, including alleys, community squares, parking lots, coworking sites, and social media sites were also described in relation to marginality in this article set, pointing to even wider typology of third places relevant to people facing precarious employment circumstances. For instance, Tan (Citation2021), Piocos (Citation2019), and Aquino et al. (Citation2020) described how migrant workers in China, Hong Kong, and Singapore used community squares to care for, be seen with, and pursue leisure with one another; Maffie (Citation2020) and Tassinari and Maccarrone (Citation2020) described gig work drivers’ use of curbs and parking lots in the United States, United Kingdom, and Italy as waiting, socializing, and collective organizing spaces between jobs; and Hamid (Citation2015) and Hamid and Tutt (Citation2019) described Tamil migrant workers’ use of alleys and street drains in Singapore as meeting points for lunch and socialization with other marginalized Tamil workers. The places described in the article set also evidenced a departure from understandings of third places as distinct from first (i.e., home) and second (i.e., work) places, instead pointing to blurred boundaries between different types of places. For example, Rossitto and Lampinen’s (Citation2018) study of so-called ‘Hoffice’ spaces described a network of sites in private homes in Sweden that people opened to fellow co-workers for occasional use; likewise, Straughan and Bissell’s (Citation2021) investigation of Australian gig workers’ social curiosity showed that interactions with customers on gig work apps and at various job sites blurred the boundary between work and social spaces.

The variety of third places described in this article set may be linked to the heterogeneity of precarious employment experiences as well as people’s diverse reasons for engaging with particular places. As described above, our scoping review utilized a broad conception of precarious employment to capture the range of circumstances in which people might lack access to a stable second (i.e., work) place. Thus, our findings include people with varied levels of stability, access to resources, and experiences of marginalization and exclusion, from temporary migrant workers in agricultural or domestic sectors to creative workers who self-selected to use co-working sites. Despite this variety, our scoping review findings suggest some common qualities of place that become attractive and necessary in precarious circumstances. Having low financial, geographical, or other barriers to regular entry, along with low obligation for participation and support for diverse ways of acting, characterize third places from community centers and public squares to coworking spaces and online message boards. For instance, migrant farmworkers in Basok and George’s (Citation2021) study needed easy access to public third places in light of their otherwise secluded work and home lives on the periphery of a Canadian town; similarly, Monticelli and Baglioni’s (Citation2017) study of young unemployed workers in Italy illustrated how financial requirements for using gyms or accessing clubs reinforced a cycle of exclusion from traditional third places that kept the workers on the periphery of their social groups.

Facilitation of resource and care exchange and fostering of collective purpose or identity was also evident across the third places described in these articles. For example, Kudejira (Citation2021) showed how food provisioning practices both maintained and reshaped social relations among Zimbabwean migrants in South Africa; Wright et al. (Citation2022) described how the provision of social support bound together the users of a co-working space in England; Yao et al.’s (Citation2021) study of gig workers in the United States and Soriano and Cabañes’ (Citation2020) study of Filipino digital workers illustrated how exchanging information and support on social media sites provided a basis for collective sensemaking, organizing, and action; and Allison (Citation2012a) described how branches of a national “time bank” in Japan allowed people to “deposit” or “withdraw” care labor with other “users and donors” who most often were strangers (p. 106). As Hamid and Tutt (Citation2019) asserted, these particular characteristics of place may be important across diverse experiences because employment precariousness is linked to “precarity of place” (p. 522): in other words, needs arising from employment precarity engendered needs for spaces that could accommodate increased flexibility, limited resources and accessibility, and feelings of marginalization.

Given the range of third places captured in this article set, it is not surprising that occupations occurring through these places demonstrated similar variety. People gathered in third places to eat, drink, socialize, exercise, engage in rest and leisure, and participate in spiritual and religious practices (see ). As discussed in the previous paragraph, within these categories of occupational engagement, people gave and received care, exchanged resources and information, and built relationships around shared experiences of precarity. Descriptions of people’s occupations often focused on their multifaceted purposes and interconnected impacts. For example, Hoang’s (Citation2016) study of Vietnamese migrant workers in Taiwan illustrated how connections formed through dancing for leisure provided foundations for troupe members to share financial resources. Petrou and Connell’s (Citation2019) study of ni-Vanuatu seasonal workers in Australia and Wu’s (Citation2021) study of Timorese workers in Australia showed how socializing on social media also provided a context for offering, soliciting, and receiving advice on navigating systems and everyday life as a seasonal worker. Landau’s (Citation2018) study of foreign migrants’ experiences in African cities and Gandini and Cossu’s (Citation2021) study of co-working spaces in England and Italy demonstrated how occupations from participation in religious services to work facilitated collective identity and relationship building.

The (re)making of third places through occupation

As we analyzed the variety and types of third places and occupations described in this data set, we developed labels to help us make sense of the dynamic relationships of occupation and place. Some places were pre-existing fixed places; this label included recreation facilities, parks, and community squares (Aquino et al., Citation2020; Basok & George, Citation2021; Hoang, Citation2016; Piocos, Citation2019; Tan, Citation2021; Tassinari & Maccarrone, Citation2020), churches (Basok & George, Citation2021; Hoang, Citation2016; Kudejira, Citation2021; Landau, Citation2018; Monticelli & Baglioni, Citation2017), non-governmental organizations and community centers (Allison, Citation2012a, Citation2012b; Piocos, Citation2019; Tungohan, Citation2017), and social media sites (Maffie, Citation2020; Petrou & Connell, Citation2019; Soriano & Cabañes, Citation2020; Tassinari & Maccarrone, Citation2020; Wu, Citation2021; Yao et al., Citation2021). Within this type of place, precarious workers often engaged in occupations that aligned with the intended purpose of the place, such as participating in religious practices in churches (Landau, Citation2018), seeking aid in non-governmental organizations (Tungohan, Citation2017), or engaging in recreation and leisure in nature spaces (Bonner-Thompson & McDowell, Citation2020). However, precarious workers sometimes also built on the intended use of pre-existing fixed places through occupational engagement to assert visibility with peers who were facing similar situations, as migrant workers did when they claimed their right to inhabit community squares (Piocos, Citation2019) and outdoor recreation locations (Aquino et al., Citation2020) despite their marginal social standing. Whether by participating in expected ways or leveraging the everyday nature of participation as a means to show that they, too, belonged in a community, precarious workers’ occupational engagement contributed to the maintenance of many pre-existing places.

Another kind of place that emerged through our analysis included transformed places such as streets and alleys (Hamid, Citation2015; Hamid & Tutt, Citation2019), parking lots (Maffie, Citation2020), and public delivery waiting points on curbs or in parks (Tassinari & Maccarrone, Citation2020). Some precarious workers transformed places through participation in occupations to meet needs that were not part of the ostensible design of those places. For instance, gig work drivers in Tassinari and Maccarrone’s (Citation2020) study utilized ‘free’ spaces at regular delivery waiting points to collectively organize and mobilize outside of their employers’ realms of social control; likewise, delivery drivers in Maffie’s (Citation2020) study congregated in an empty parking lot after regular business hours to socialize and talk about work. Additionally, Australian urban gig workers’ engagement with gig work applications transformed those virtual spaces from ‘help wanted’ task lists into places that fulfilled social opportunity and curiosity (Straughan & Bissell, Citation2021). Sometimes, precarious workers transformed places through occupation because they were excluded from or lacked access to existing places, as was the case of migrant workers who made street drains and alleys into places to eat meals and socialize with fellow migrants in Singapore’s Little India neighborhood (Hamid, Citation2015; Hamid & Tutt, Citation2019). These transformations of place occurred as precarious workers moved throughout their broader daily routines, occurring both within and between engagement in work occupations.

Finally, precarious workers also created new places within larger networks through occupation to meet social and economic needs and build community ties. For example, Allison’s (Citation2012a, Citation2012b) study described ‘regional living rooms’ that were designed to bring local groups of people—including young precarious workers and aging adults—together to counter social isolation and loneliness in broader Japanese society; each regional living room was forged through occupations of care and resource provision and receipt, performance and witnessing, and eating. Similarly, Rossitto and Lampinen (Citation2018), Gandini and Cossu (Citation2021), and Wright et al. (Citation2022) all described the ways in which people created coworking spaces through organizational, social, supportive, and productive occupations to address multiple needs, counter prevailing corporate workplace culture, and build social ties amongst precarious workers across a variety of industries. Overall, across pre-existing, transformed, and new places, precarious workers utilized their occupations to create, maintain, and participate in places to meet interconnected social, material, and emotional needs.

Discussion

Consistent with contemporary scholarship on third places, these scoping review findings broaden knowledge about the types of third places that exist and the ways in which they contribute to people’s lives. Beyond being sites of “pure sociability” (Oldenburg & Brissett, Citation1982, p. 273), third places can be sites for ensuring survival, caring for others, resisting marginalization, and expressing solidarity. Thus, third places meet a range of needs that enable people to cope with and navigate the conditions of everyday life. Such multiplicity of purpose underscores the essential nature of third places in society. Based on our analysis, characteristics that foster accessibility, multiple forms of participation, and an open atmosphere are key to the potential of third places to meet a range of needs for diverse users. Our analysis also shows that the kinds of third places highlighted by Oldenburg (Citation1999), such as restaurants and bars, may not only be financially inaccessible to some people, but their design for paying customers and the attitudes of those occupying such places may also intensify feelings of exclusion, putting marginalized groups’ uncertain and unstable life circumstances into sharp relief. These findings highlight two needs for reconceptualizing and re-designing third places: expanding the types of places that are seen as constituting third places, and critically assessing the design and social milieu of existing and emerging third places to understand—and minimize—their exclusionary potential. These needs for reconceptualization dovetail with Yuen and Johnson’s (Citation2017) reflections on the limitations of Oldenburg’s original framing of third places as public places.

In addition to the above understandings, our scoping review revealed opportunities to strengthen research on third places. As described previously, the original referent group used to establish the concept of third places did not specifically include people outside white, American, male, full-time employed, middle-class individuals. Although this scoping review aimed to broaden the referent group by focusing on precarious workers, none of the 24 included studies examined the experiences of racialized non-migrant men and women, aging and older workers, or persons experiencing cyclical unemployment. Such groups are among the most vulnerable for intersecting work and social precarity (Lewchuk et al., Citation2016), and their experiences with third places may further augment understandings derived from existing studies. Within the article set, studies’ emphasis on foreign temporary workers and migrant workers may signal research funders’ and policy makers’ warranted interest in those groups; however, there is a need to also recognize that precarity is an increasingly common experience for residents and citizens who experience precarity at the intersection of various intersectional identities. Research that aims to understand how third places fit into the “new normal” (Harris & Nowicki, Citation2018, p. 378) of precarious lives thus needs to start by questioning who is presumed to experience precarity, what sorts of third places particular groups of people might access or create, what forms of occupation are enacted within such places, and what varied needs third places might fulfill in their everyday lives.

Implications for occupational science

As established above, extant research has tended to overlook the things people do in third places beyond socializing. Our scoping review findings illustrate that people do many things in third places, often for multiple, overlapping purposes related to the conditions of their everyday lives. Occupational scientists are positioned to bring the ‘doing’ dimensions of third places forward in ways that situate socializing and other valued experiences within an array of co-occurring occupations, thus providing a more fulsome view of the functions that third places serve. Occupational scientists can also inquire about similarities and differences in occupational engagement across different kinds of third places (e.g., physical versus virtual third places), thus answering existing calls to broaden understandings about third places (Yuen & Johnson, Citation2017).

Findings from this scoping review also highlight opportunities to expand existing lines of occupational science inquiry. A decade ago, Johansson et al. (Citation2013) suggested that an occupational perspective could further develop knowledge about placemaking processes. Since that time, occupational scientists have made relevant theoretical and empirical contributions to disciplinary thinking, for instance, by drawing on Lefebvre’s (1991) notion of “the spatial triad” to counter dualistic understandings of place and space (Delaisse, Huot, & Veronis, Citation2021) and foreground how occupational participation produces space (Delaisse, Huot, Veronis, & Mortenson, Citation2021). Specific to the topic of precariousness and work, occupational scientists have illustrated how precarity is both experienced through and manifested in everyday spatial mobilities in situations outside stable employment (Huot et al., Citation2022). Occupational scientists have also shared knowledge beyond the discipline, for example, by conveying to geographers and gerontologists how active person-place relationships can be understood through the lens of occupation (Cutchin, Citation2017; Hand et al., Citation2020). These current directions in occupational science dovetail with opportunities to theorize and analyze the active production, maintenance, and re-making of third places.

By bringing an occupational perspective to research on third places, occupational scientists also have the opportunity to extend the reach of conceptual developments within the discipline. Understandings about the process of place integration (e.g., Cutchin Citation2004; Wijekoon et al., Citation2021) may be particularly useful for elucidating changes in access to or engagement with third places that are fostered by broader life transitions. Knowledge of collective occupations (e.g., Kantartzis, Citation2016; Ramugondo & Kronenberg, Citation2015) can draw attention to the ways in which third places are (re)created through shared ways of participation; such a focus can also highlight the ways in which collective dynamics may contribute to experiences of exclusion in third places. Applications of a transactional perspective to community-level phenomena (e.g., Cutchin et al., Citation2017; Lavalley, Citation2017) can further cement the need to focus placemaking inquiries at the level of the situation and frame individual and collective action as dynamic elements of that whole. Finally, scholarship on occupation as a vehicle for social transformation (e.g., Laliberte Rudman et al., Citation2019; Schiller et al., Citation2022) can be used to explore the ways in which (re)making third places through occupation can help reduce precariousness and its negative impacts on people’s everyday lives, while also building social cohesion and belonging. As Kantartzis and Molineux (Citation2017) suggested, there are opportunities for occupational scientists to partner in community development work related to third places; such efforts can answer the call issued by Thompson and Kent (Citation2014) and echoed in this scoping review’s findings regarding the need to design third places to be “inclusive and supportive” (p. 34).

Limitations

The findings of this scoping review, as well as their implications, must be understood with some limitations in mind. As noted previously, many of the articles included in this scoping review lacked sufficient detail to fully assess their rigor, sincerity, and credibility. We also restricted our search to articles published in English, thus excluding potentially significant work published in different languages. More broadly, although our search strategy attempted to encompass the variety of terms that may have been used to index relevant research, the complexity of each subject category (i.e., third places, precarious work, and social isolation) makes it difficult to claim completely comprehensive scoping review results.

Conclusion

The state of knowledge about third places is characterized by opportunities for conceptual and empirical development. Through a report of scoping review findings, we have attempted to illustrate how a greater focus on third places can be fruitful for occupational science, providing opportunities to extend understandings about placemaking, place integration, collective occupation, a transactional perspective, and the socially transformative potential of occupation. We believe that occupational scientists can partner with other researchers as well as advocates, community members, and policy makers to unlock the full potential of third places to meet the broad needs of diverse social groups.

Acknowledgements

We honor the Tongva people and the Anishinaabek, Haudenosaunee, Lūnaapéewak and Chonnonton Nations, whose traditional territories are where this paper was produced in the United States of America and Canada. These lands continue to be home to diverse Indigenous Peoples (First Nations, Métis, and Inuit) whom we recognize as contemporary stewards of the land and vital contributors of our society.

Acknowledgements are extended to two additional student trainees, Randee Elias and Joana Akrofi, who assisted with text management and screening. This work was supported by the Canadian Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council under Knowledge Synthesis Grant #872-2021-0024. The work is also informing on-going work on third places supported by the Canadian Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council under Insight Grant #435-2022-0977.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Akbar, P. N. G., & Edelenbos, J. (2021). Positioning placemaking as a social process: A systematic literature review. Cogent Social Sciences, 7(1), Article 1905920. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.1905920

- Allison, A. (2012a). A sociality of, and beyond, “my-home” in post-corporate Japan. Cambridge Anthropology, 30(1), 95–108. https://doi.org/10.3167/ca.2012.300109

- Allison, A. (2012b). Ordinary refugees: Social precarity and soul in 21st century Japan. Anthropological Quarterly, 85(2), 345–370. https://doi.org/10.1353/anq.2012.0027

- Aquino, K., Wise, A., Velayutham, S., Parry, K. D., & Neal, S. (2020). The right to the city: Outdoor informal sport and urban belonging in multicultural spaces. Annals of Leisure Research, 25(4), 472-490. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2020.1859391

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Bajwa, U., Gastaldo, D., Di Ruggiero, E., & Knorr, L. (2018). The health of workers in the global gig economy. Globalization and Health, 14(1), Article 124. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-018-0444-8

- Bak, C. K. (2018). Definitions and measurement of social exclusion—A conceptual and methodological review. Advances in Applied Sociology, 8, 422–443. https://doi.org/10.4236/aasoci.2018.85025

- Basok, T., & George, G. (2021). “We are part of this place, but I do not think I belong.” Temporariness, social inclusion and belonging among migrant farmworkers in Southwestern Ontario. International Migration, 59(5), 99–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12804

- Benjamin Thomas, T. E., & Laliberte Rudman, D. (2018). A critical interpretive synthesis: Use of the occupational justice framework in research. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 65, 2–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12428

- Bonner-Thompson, C., & McDowell, L. (2020). Precarious lives, precarious care: Young men’s caring practices in three coastal towns in England. Emotion, Space and Society, 35, Article 100684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2020.100684

- Brien, S. E., Lorenzetti, D. L., Lewis, S., Kennedy, J., & Ghali, W. A. (2010). Overview of a formal scoping review on health system report cards. Implementation Science, 5, Article 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-2

- Burchardt, T., Le Grand, J., & Piachaud, D. (2002). Introduction. In J. Hills, J. Le Grand, & D. Piachaud (Eds.), Understanding social exclusion (pp. 1–12). Oxford University Press.

- Colquhoun, H. L., Levac, D., O’Brien, K. K., Straus, S., Tricco, A. C., Perrier, L., Kastner, M., & Moher, D. (2014). Scoping reviews: Time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(12), 1291–1294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013

- Cresswell, T. (2015). Place: An introduction (2nd ed.). Wiley Blackwell.

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). (2021). CASP checklists. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

- Cutchin, M. P. (2004). Using Deweyan philosophy to rename and reframe adaptation-to-environment. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 58(3), 303–312. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.58.3.303

- Cutchin, M. P. (2017). Active relationships of ageing people and places. In M. W. Skinner, G. J. Andrews, & M. P. Cutchin (Eds.), Geographical gerontology: Perspectives, concepts, approaches (pp. 216–228). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315281216

- Cutchin, M. P., Dickie, V. A., & Humphry, R. A. (2017). Foregrounding the transactional perspective’s community orientation. Journal of Occupational Science, 24(4), 434–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2017.1365750

- Czech, K., Davy, A., & Wielechowski, M. (2021). Does the COVID-19 pandemic change human mobility equally worldwide? Cross-country cluster analysis. Economies, 9(4), Article 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies9040182

- de Jong Gierveld, J., Van Tilburg, T., & Dykstra, P. A. (2006). Loneliness and social isolation. In A. L. Vangelisti & D. Perlman (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of personal relationships (pp. 485–500). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511606632.027

- Delaisse, A. C., Huot, S., & Veronis, L. (2021). Conceptualizing the role of occupation in the production of space. Journal of Occupational Science, 28(4), 550–560. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2020.1802326

- Delaisse, A. C., Huot, S., Veronis, L., & Mortenson, W. B. (2021). Occupation’s role in producing inclusive spaces: Immigrants’ experiences in linguistic minority communities. OTJR: Occupational Therapy Journal of Research, 41(2), 124–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/1539449220981952

- Dickie, V. A., Cutchin, M. P., & Humphry, R. (2006). Occupation as transactional experience: A critique of individualism in occupational science. Journal of Occupational Science, 13(1), 83–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2006.9686573

- Dixon-Woods, M., Cavers, D., Agarwal, S., Annandale, E., Arthur, A., Harvey, J., Hsu, R., Katbamna, S., Olsen, R., Smith, L., Riley, R., & Sutton, A. J. (2006). Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 6(35), Article 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-6-35

- Dolley, J., & Bosman, C. (2019). Rethinking third places: Informal public space and community building. Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781786433916

- Finlay, J., Esposito, M., Kim, M. H., Gomez-Lopez, I., & Clarke, P. (2019). Closure of ‘third places’? Exploring potential consequences for collective health and wellbeing. Health & Place, 60, Article 102225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.102225

- Fullagar, S., O’Brien, W., & Lloyd, K. (2019). Feminist perspectives on third places. In J. Dolley & C. Bosman (Eds.), Rethinking third places - Informal public places and community building (pp. 20–37). Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781786433916.00010

- Gandini, A., & Cossu, A. (2021). The third wave of coworking: ‘Neo-corporate’ model versus ‘resilient’ practice. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 24(2), 430–447. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549419886060

- Gidley, J., Hampson, G., Wheeler, L., & Bereded-Samuel, E. (2010). Social inclusion: Context, theory, and practice. The Australian Journal of University-Community Engagement, 5(1), 6–38.

- Gonçalves, M. V., & Malfitano, A. P. S. (2020). Brazilian youth experiencing poverty: Everyday life in the favela. Journal of Occupational Science, 27(3), 311–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2020.1757495

- Grenier, A., Phillipson, C., Laliberte Rudman, D., Hatzifilalithis, S., Kobayashi, K., & Marier, P. (2017). Precarity in late life: Understanding new forms of risk and insecurity. Journal of Aging Studies, 43, 9–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2017.08.002

- Hamid, W. (2015). Feelings of home amongst Tamil migrant workers in Singapore’s Little India. Pacific Affairs, 88(1), 5–25. https://doi.org/10.5509/20158815

- Hamid, W., & Tutt, D. (2019). “Thrown away like a banana leaf”: Precarity of labour and precarity of place for Tamil migrant construction workers in Singapore. Construction Management and Economics, 37(9), 513–536. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2019.1595075

- Hand, C., Laliberte Rudman, D., Huot, S., Gilliland, J. A., & Pack, R. L. (2018). Toward understanding person–place transactions in neighborhoods: A qualitative-participatory geospatial approach. The Gerontologist, 58(1), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnx064

- Hand, C., Laliberte Rudman, D., Huot, S., Park, R., & Gilliand, J. (2020). Enacting agency: Exploring how older adults shape their neighbourhoods. Ageing & Society, 40(3), 565–583. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X18001150

- Hand, C., & Letts, L. (2009). Occupational therapy research and practice involving adults with chronic diseases: A scoping review and internet scan. Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists.

- Hand, C., Prentice, K., McGrath, C., Laliberte Rudman, D., & Donnelly, C. (2023). Contested occupation in place: Experiences of inclusion and exclusion in seniors’ housing. Journal of Occupational Science, 30(1), 94–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2022.2125897

- Harris, K., Krygsman, S., Waschenko, J., & Laliberte Rudman, D. (2018). Ageism and the older worker: A scoping review. The Gerontologist, 58(2), e1–14. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw194

- Harris, E., & Nowicki, M. (2018). Cultural geographies of precarity. Cultural Geographies, 25(3), 387–391. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474018762812

- Hart, E. C., & Heatwole Shank, K. (2016). Participating at the mall: Possibilities and tensions that shape older adults’ occupations. Journal of Occupational Science, 23(1), 67–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2015.1020851

- Haslam, C., Cruwys, T., Haslam, S. A., & Jetten, J. (2015). Social connectedness and health. In N. Pachana (Ed.), Encyclopedia of geropsychology. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-080-3_46-1

- Heatwole Shank, K., & Cutchin, M. P. (2010). Transactional occupations of older women aging-in-place: Negotiating change and meaning. Journal of Occupational Science, 17(1), 4–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2010.9686666

- Hickman, P. (2013). “Third places” and social interaction in deprived neighbourhoods in Great Britain. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 28(2), 221–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-012-9306-5

- Hoang, L. A. (2016). Vietnamese migrant networks in Taiwan: The curse and boon of social capital. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 39(4), 690–707. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2015.1080381

- Hocking, C. (2021). Occupation in context: A reflection on environmental influences on human doing. Journal of Occupational Science, 28(2), 221–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2019.1708434

- Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614568352

- Hung, L., Hudson, A., Gregorio, M., Jackson, L., Mann, J., Horne, N., Berndt, A., Wallsworth, C., Wong, L., & Phinney, A. (2021). Creating dementia-friendly communities for social inclusion: A scoping review. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/23337214211013596

- Huot, S., Aldrich, R. M., Laliberte Rudman, D., & Stone, M. (2022). Picturing precarity through occupational mapping: Making the (im)mobilities of long-term unemployment visible. Journal of Occupational Science, 29(4), 529–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2020.1821244

- Huot, S., & Veronis, L. (2018). Examining the role of minority community spaces for enabling migrants’ performance of intersectional identities through occupation. Journal of Occupational Science, 25(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2017.1379427

- Jakobsen, K. (2004). If work doesn’t work: How to enable occupational justice. Journal of Occupational Science, 11(3), 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2004.9686540

- Johansson, K., Laliberte Rudman, D., Mondaca, M., Park, M., Luborsky, M., Josephsson, S., & Asaba, E. (2013). Moving beyond ‘aging in place’ to understand migration and aging: Place making and the centrality of occupation. Journal of Occupational Science, 20(2), 108–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2012.735613

- Kantartzis, S. (2016). Exploring occupation beyond the individual: Family and collective occupation. In D. Sakellariou & N. Pollard (Eds.), Occupational therapies without borders: Integrating justice with practice (2nd ed., pp. 19–28). Elsevier.

- Kantartzis, S., & Molineux, M. (2017). Collective occupation in public spaces and the construction of the social fabric. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 84(3), 168–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417417701936

- Keefe, J., Andrew, M., Fancey, P. and Hall, M. (2006). Final report: A profile of social isolation in Canada. British Columbia Ministry of Health. https://www.health.gov.bc.ca/library/publications/year/2006/keefe_social_isolation_final_report_may_2006.pdf

- Kudejira, D. (2021). The role of “food” in network formation and the social integration of undocumented Zimbabwean migrant farmworkers in the Blouberg-Molemole area of Limpopo, South Africa. Anthropology Southern Africa, 44(1), 16–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/23323256.2021.1892498

- Kwon, J. B., & Lane, C. M. (Eds.). (2016). Anthropologies of unemployment: New perspectives on work and its absence. Cornell University Press.

- Laliberte Rudman, D., & Huot, S. (2012). Conceptual insights for expanding thinking regarding the situated nature of occupation. In M. P. Cutchin & V. A. Dickie (Eds.), Transactional perspectives on occupation (pp. 51–63). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4429-5_5

- Laliberte Rudman, D., Pollard, N., Craig, C., Kantartzis, S., Piškur, B., Algado Simó, S., van Bruggen, H., & Schiller, S. (2019). Contributing to social transformation through occupation: Experiences from a think tank. Journal of Occupational Science, 26(2), 316–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2018.1538898

- Landau, L. B. (2018). Friendship fears and communities of convenience in Africa’s urban estuaries: Connection as measure of urban condition. Urban Studies, 55(3), 505–521. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017699563

- Lavalley, R. (2017). Developing the transactional perspective of occupation for communities: “How well are we doing together?” Journal of Occupational Science, 24(4), 458–469. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2017.1367321

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), Article 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- Lewchuk, W., & Laflèche, M. (2017). Precarious employment: What it means for workers and their families. In R. J. Burke & K. M. Page (Eds.), Research handbook on work and well-being (pp. 150–169). Edward Elgar.

- Lewchuk, W., Laflèche, M., Procyk, S., Cook, C., Dyson, D., Goldring, L., Lior, K., Meisner, A., Shields, J., Tambureno, A., & Viducis, P. (2016). The precarity penalty: How insecure employment disadvantages workers and their families. Alternate Routes, 27, 87–108. https://www.alternateroutes.ca/index.php/ar/article/view/22394

- Lightfoot, A., Janemi, R., & Laliberte Rudman, D. (2018). Perspectives of North American postsecondary students with learning disabilities: A scoping review. Journal of Postsecondary Disability and Education, 31, 57–74. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1182368.pdf

- Littman, D. M. (2021). Third place theory and social work: Considering collapsed places. Journal of Social Work, 21(5), 1225–1242. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017320949445

- Madsen, J., & Josephsson, S. (2017). Engagement in occupation as an inquiring process: Exploring the situatedness of occupation. Journal of Occupational Science, 24(4), 412–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2017.1308266

- Maffie, M. D. (2020). The role of digital communities in organizing gig workers. Industrial Relations, 59(1), 123–149. https://doi.org/10.1111/irel.12251

- May, B. (2019). Precarious work: Understanding the changing nature of work in Canada. Standing Committee on Human Resources, Skills and Social Development and the Status of Persons with Disabilities, House of Commons, Canada. https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/HUMA/Reports/RP10553151/humarp19/humarp19-e.pdf

- McCarthy, K., Rice, S., Flores, A., Miklos, J., & Nold, A. (2022). Exploring the meaningful qualities of transactions in virtual environments for massively multiplayer online role-playing gamers. Journal of Occupational Science, 30(1), 81–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2022.2108884

- Monticelli, L., & Baglioni, S. (2017). Aspiring workers or striving consumers? Rethinking social exclusion in the era of consumer capitalism. Contemporary Social Science, 12(3-4), 316–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/21582041.2017.1385834

- Morgan, T., Wiles, J., Park, H., Moeke-Maxwell, T., Dewes, O., Black, S., Williams, L., & Gott, M. (2021). Social connectedness: What matters to older people? Ageing and Society, 41(5), 1126–1144. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X1900165X

- Muñoz, S. (2018). Precarious city: Home-making and eviction in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Cultural Geographies, 25(3), 411–424. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474017719068

- Nhunzvi, C., Langhaug, L., Mavindidze, E., Harding, R., & Galvaan, R. (2019). Occupational justice and social inclusion in mental illness and HIV: A scoping review protocol. BMJ Open, 9, e024049. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024049

- Nicholson, N. R. (2012). A review of social isolation: An important but underassessed condition in older adults. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 33, 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-012-0271-2

- Oldenburg, R. (1989). The great good place: Cafés, coffee shops, community centers, beauty parlors, general stores, bars, hangouts, and how they get you through the day. Paragon House.

- Oldenburg, R. (1999). The great good place: Cafes, coffee shops, bookstores, bars, hair salons, and other hangouts at the heart of a community (3rd ed.). Marlowe & Company.

- Oldenburg, R., & Brissett, D. (1982). The third place. Qualitative Sociology, 5(4), 265–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00986754

- O’Rourke, H. M., & Sidani, S. (2017). Definition, determinants, and outcomes of social connectedness for older adults: A scoping review. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 43(7), 43–52. http://doi.org/10.3928/00989134-20170223-03

- Oxoby, R. (2009). Understanding social inclusion, social cohesion, and social capital. International Journal of Social Economics, 36(12), 1133–1152. https://doi.org/10.1108/03068290910996963

- Peralta-Catipon, T. (2009). Statue square as a liminal sphere: Transforming space and place in migrant adaptation. Journal of Occupational Science, 16(1), 32–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2009.9686639

- Peters, M., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., McInerney, P., Godfrey, C. M., & Khalil, H. (2020). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 18(10), 2119–2126. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBIES-20-00167

- Petrou, K., & Connell, J. (2019). Overcoming precarity? Social media, agency and ni-Vanuatu seasonal workers in Australia. Journal of Australian Political Economy, 2019(84), 116–146. https://www.ppesydney.net/content/uploads/2020/05/Overcoming-precarity-Social-media-agency-and-ni-Vanuatu-seasonal-workers-in-Australia.pdf

- Pham, M. T., Rajić, A., Greig, J. D., Sargeant, J. M., Papadopoulos, A., & McEwen, S. A. (2014). A scoping review of scoping reviews: Advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Research Synthesis Methods, 5(4), 371–385. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1123

- Piocos III, C. M. (2019). At home in public: Intimacy and belonging among Filipina and Indonesian migrant domestic workers in Hong Kong in Ani Ema Susanti’s Effort for Love (2008) and Moira Zoitl’s Exchange Square (2007). Plaridel, 16(2), 161–181. https://doi.org/10.52518/2020.16.2-07piocos

- Popov, A. V., & Solov’eva, T. S. (2019). Analyzing and classifying the implications of employment precarization: Individual, organizational and social levels. Economic and Social Changes, 12(6), 182–196. https://doi.org/10.15838/esc.2019.6.66.10

- Ramugondo, E. L., & Kronenberg, F. (2015). Explaining collective occupations from a human relations perspective: Bridging the individual-collective dichotomy. Journal of Occupational Science, 22(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2013.781920

- Ross, F. M. (1998). Occupational bliss or occupational stress: Managing mental health in work contexts. Journal of Occupational Science, 5(3), 155–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.1998.9686444

- Rossitto, C., & Lampinen, A. (2018). Co-creating the workplace: Participatory efforts to enable individual work at the Hoffice. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW), 27(3), 947–982. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10606-018-9319-z

- Rowles, G. D. (2008). Place in occupational science: A life course perspective on the role of environmental context in the quest for meaning. Journal of Occupational Science, 15(3), 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2008.9686622

- Scharf, T., Phillipson, C., & Smith, A. E. (2005). Social exclusion of older people in deprived urban communities of England. European Journal of Ageing, 2, 76–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-005-0025-6

- Schiller, S., van Bruggen, H., Kantartzis, S., Laliberte Rudman, D., Lavalley, R., & Pollard, N. (2022). “Making change by shared doing”: An examination of occupation in processes of social transformation in five case studies. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2022.2046153

- Soriano, C. R. R., & Cabañes, J. V. A. (2020). Entrepreneurial solidarities: Social media collectives and Filipino digital platform workers. Social Media + Society, 6(2), 947–982. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120926484

- Straughan, E. R., & Bissell, D. (2021). Curious encounters: The social consolations of digital platform work in the gig economy. Urban Geography, 43(9), 1309–1327. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2021.1927324

- Tan, Y. (2021). Temporary migrants and public space: A case study of Dongguan, China. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47(20), 4688–4704. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1732615

- Tassinari, A., & Maccarrone, V. (2020). Riders on the storm: Workplace solidarity among gig economy couriers in Italy and the UK. Work, Employment and Society, 34(1), 35–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017019862954

- Thompson, S., & Kent, J. (2014). Healthy built environments supporting everyday occupations: Current thinking in urban planning. Journal of Occupational Science, 21(1), 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2013.867562

- Townsend, K. C., & McWhirter, B. T. (2005). Connectedness: A review of the literature with implications for counseling, assessment, and research. Journal of Counseling and Development, 83(2), 191–201. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2005.tb00596.x

- Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative inquiry, 16(10), 837–851. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410383121

- Tungohan, E. (2017). From encountering confederate flags to finding refuge in spaces of solidarity: Filipino temporary foreign workers’ experiences of the public in Alberta. Space and Polity, 21(1), 11–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562576.2017.1270637

- Waite, L. (2009). A place and space for a critical geography of precarity? Geography Compass, 3(1), 412–433. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2008.00184.x

- Wicks, A. (2014). Editorial: Special issue on population health. Journal of Occupational Science, 21(1), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2014.891289

- Wigfield, A., Turner, R., Alden, S., Green, M., & Karania, V. K. (2022). Developing a new conceptual framework of meaningful interaction for understanding social isolation and loneliness. Social Policy and Society, 21(2), 172–193. https://doi.org/10.1017/S147474642000055X

- Wijekoon, S., Laliberte Rudman, D., Hand, C., & Polgar, J. (2021). Late-life immigrants’ place integration through occupation. Journal of Occupational Science, 30(1), 37–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2021.1960589

- Williams, S. A., & Hipp, J. R. (2019). How great and how good? Third places, neighbor interaction, and cohesion in the neighborhood context. Social Science Research, 77, 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2018.10.008

- Wright, A., Marsh, D., & Wibberley, G. (2022). Favours within ‘the tribe’: Social support in coworking spaces. New Technology, Work and Employment, 37(1), 59–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/ntwe.12214

- Wu, A. Y. C. (2021). Migration, family and networks: Timorese seasonal workers’ social support in Australia. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 62(1), 313–330. https://doi.org/10.1111/apv.12308

- Yao, Z., Weden, S., Emerlyn, L., Zhu, H., & Kraut, R. E. (2021). Together but alone: Atomization and peer support among gig workers. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 5(2), Article 391. https://doi.org/10.1145/3479535

- Yuen, F., & Johnson, A. J. (2017). Leisure spaces, community, and third places. Leisure Sciences, 39(3), 295–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2016.1165638

- Zavaleta, D., Samuel, K., & Mills, C. (2014). Social isolation: A conceptual and measurement proposal. OPHI Working Papers 67. University of Oxford. https://www.ophi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/ophi-wp-67.pdf